1. Introduction

Underground space represents a strong catalyzing element for the creation of sustainable urban development, as well as long-term economic and social growth. In the last decade, many projects located underground have captured the attention of people worldwide. In fact, the use, and reuse of underground space has been increasingly recognized as a valuable tool for sustainable urban development and in many countries, and has often been elevated to a strategic level for long-term economic and social planning. Traditionally, sanitary and water networks, transport, natural resources and social conflict management have been the functional sectors involved, but in recent years the interaction with risk management, cultural heritage valorization and smart planning has increasing attention. Today, planners, environmentalists, architects, engineers, policy makers, archaeologists and economists are encouraged to work together in order to ensure that planning and development can meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to thrive, while safeguarding historical underground stratifications. Since energy-saving and eco-friendly construction approaches have become an important part of modern development, with a special emphasis on resource optimization, underground planning has acquired a key role in ensuring that these solutions as well as new materials and processes are incorporated in the most efficient manner. At the same time, in an apparent contrast to this approach, underground space is also revealing good potential in the communication of cultural values in both urban and rural contexts, encouraging an increasing number of monitoring, preservation and divulgation initiatives. Consequently, in addition to being based on the pre-existing, solid, diffused and highly specialized knowledge, urban underground regeneration now also includes cooperative actions.

Indeed, an increasing number of international research groups are now focusing on creating partnerships that promote the concerted effort of researchers and local administrators (in both the public and private sectors) with reference to the development of indoor spaces. An example is the very first attempt in this direction made by the Observatoire de la Ville Intérieure in 2002 for the city of Montreal [

1]. Also, associated research centers for the urban underground space (ACUUS) [

2] have consolidated their reputation (since 2002) by supporting partnerships amongst experts who design, analyze and decide on the use of our cities’ underground spaces on a cooperative basis. The International Tunneling and Underground Space Association (ITACUS) [

3] sees its mission “to advance the awareness and thinking on the use of underground space through the creation of a worldwide dialogue”. ITACUS works closely with its global partners (ISOCARP, ICLEI, IFME and UNISDR) and UN Habitat to develop the ‘think deep’ culture. It is on the way towards a new program, entitled the “Young Professional’s Think Deep Program”, which promotes the stimulation of interaction among interdisciplinary professionals from the underground built environment.

The increasing number of people, urbanization level and mobility needs, constitute the driving forces for the construction and expansion of underground transport systems. ExpoTunnel is the exhibition dedicated to the world of tunneling, drilling, mining, underground construction and research [

4]. According to the new trends, underground transports must not be seen as incompatible infrastructures within historical cities but, on the contrary, following the example of the Linea 1 Metro in Naples, a good opportunity to combine underground cultural heritage rediscovery, preservation and valorization within new efficient transport systems [

5].

Furthermore, risks management approaches have generated cooperative actions. Hypogea [

6] is an international multidisciplinary network established in 2015, focused on the exploitation, cultural and economic importance, hazards, remediation and rehabilitation, surveying, mapping, and dating techniques of the artificial cavities.

In spite of the above-mentioned trends, in terms of a functional approach, underground space use, or its reconversion, is still generally associated with the relocation of surface land uses or activities when on ground level installation is difficult, impractical, less profitable or even environmentally unsustainable [

7]. This negative yet resistant approach could be overcome by adopting large scale cooperative actions according to the new trends developed by Broere [

8] who introduced the preservation of existing buildings and cultural heritage as a significant variable in underground planning.

As briefly mentioned, underground space is a popular topic that stimulates international and multidisciplinary research with the aim to interconnect urban history and urban planning. However, when the underground experience is so extreme that the city itself was built below the ground’s surface, the inclusion of the corresponding valorization elements of cultural heritage within city planning requires more attention and specific skills. In this case, the traditional building concept is inverted, and the edification stems from a complex technique based on quarrying and removal rather than from vertical construction; this approach is called in this paper ‘negative building culture’. Instead of shaped rocks, bricks or various mixtures being used to build spaces for public or private uses, the natural material of the solid rock is removed in order to create the required space for urban life. This strategy became necessary, and sometimes still is, in order to solve the problems of safety, adverse climatic conditions or lack of water. Underground uses vary from one area to another, but nearly always they provide solutions for dwellings and shelters, and always prove to be among the most environmentally friendly models of urban development and the management of water and energy resources; they are indeed study cases for our modern bio-architecture, and simultaneously places of enormous potential for tourism, as they belong to the local cultural heritage. Historic negative built settlements have been at the core of several projects dedicated to their study, classification and valorization, not only as significant elements of cultural heritage but, even, to experience their reconversion according to the rules of “best practices in architecture”. However, balancing actions between the total preservation of those spaces and their potential contemporary use and facing, at the same time, the demand for private and public urban functions is not an easy task.

The methodology developed by the author and introduced in this paper has got three different steps: the first is the definition of the class of cultural elements that are under analysis, the underground built heritage (UBH). This new classification should be considered an updated version of the first classification for artificial cavities outlined in 2013 by the UIS Commission [

9] and was appositely studied to be used as an instrument of analysis for historical caved artifacts in consideration of their cultural value and their contemporary use. The second step of the methodological approach is dedicated to the definition of the historical use of the selected class of cultural assets. The third focuses on the analysis of the actions operated in the direction of their enhancement and valorization. The above-mentioned methodological approach is a very flexible instrument, applicable to different geographic and historical contexts; it was also conceived to allow for comparative analysis.

The case study analyzed in the paper is the site of Sassi in Matera (Southern Italy), a carved city which was completely transformed from a poor, neglected and stigmatized rural village until the first decades of 19th century, to a top touristic destination and a perfect example of a reborn city on the basis of its historical and cultural value. This paper, thanks to the application of the methodological approach, focuses on the difficulties in facing modern gentrification and analyses how Sassi experienced the “ethical conservation for architecture” [

10] in order to face it, and preserve the communication of historical functions in selected elements of UBH. The transformation of Sassi is at the basis of the nomination of Matera as European Capital of Culture in 2019, but this success, rather than being considered as the final goal, should be seen as an opportunity to consolidate the position of the city within worldwide challenges regarding underground cultural heritage.

2. The Methodology: Definition of Underground Built Heritage and Introduction to Dynamic Classification Addressed to RE-USE

Underground built heritage (UBH) is the class which collects all historical artifacts caved underground, and which can be considered today as significant elements of local cultural heritage. Elements of UBH are built underground in order to manage several aboveground environmental conflicts and social interactions; this group includes a wide range of artificial caves, or natural caves adapted for human uses, with different morphologic characters, variable historical significance and rarity. The underground aspect is a necessary element but is not a sufficient one. To be included in UBH, historical caved spaces must have successfully interacted with, and interpreted, selected historical local linkages, or been the result of successful attempts in the adaptation to local natural heritage through the application of that specific segment of vernacular architecture [

11] that in this paper is named ‘negative building’ culture or ‘troglodyte’ to underline its typical character. In fact, in UBH, the location is not casual, it is a conscious and purposeful adaptation to geological, climatic, geographical and political situations with the application of selected skills, technologies and professional abilities by local communities.

With such a definition, it is evident that not all historical galleries, or aqueducts or sewer pipes can be included in that class: the diffusion or the rarity of the correspondent artifacts is not the only variable to be considered; there can be diffuse underground elements that are part of local UBH and very rare caved artifacts that are not suitable for inclusion.

The definition of the UBH class necessarily introduced a new classification chart. In fact, if all the elements included in the UBH class can be listed in the classification established in 2013 by the Artificial Cavities Commission (UIS), the contrary is not always true. In that classification, the selection criteria include the age of the artifact, technique adopted and prevalent use. With reference to the last aspect, there are six classes (articulated in thirty-seven subclasses) plus an additional class for those “not classified” [

9]. That classification is ideal for the static representation of sites but is not adequate for the visualization of their evolution through time, which is not only the most meaningful attribute in terms of the proposed approach, but also highly recommended in all the actions addressed to fundraising with reference to the valorization of urban and rural UBH.

For that reason, despite the UIS classification being a fundamental support for a preliminary approach to UBH, the definition of guidelines for analysis and planning of the valorization processes, based on the capitalization of values and skills detained by the considered elements, required a new classification chart. This new instrument of analysis is expected to also reconstruct all the transformations in shape and functions that may have occurred during the history of the UBH under evaluation.

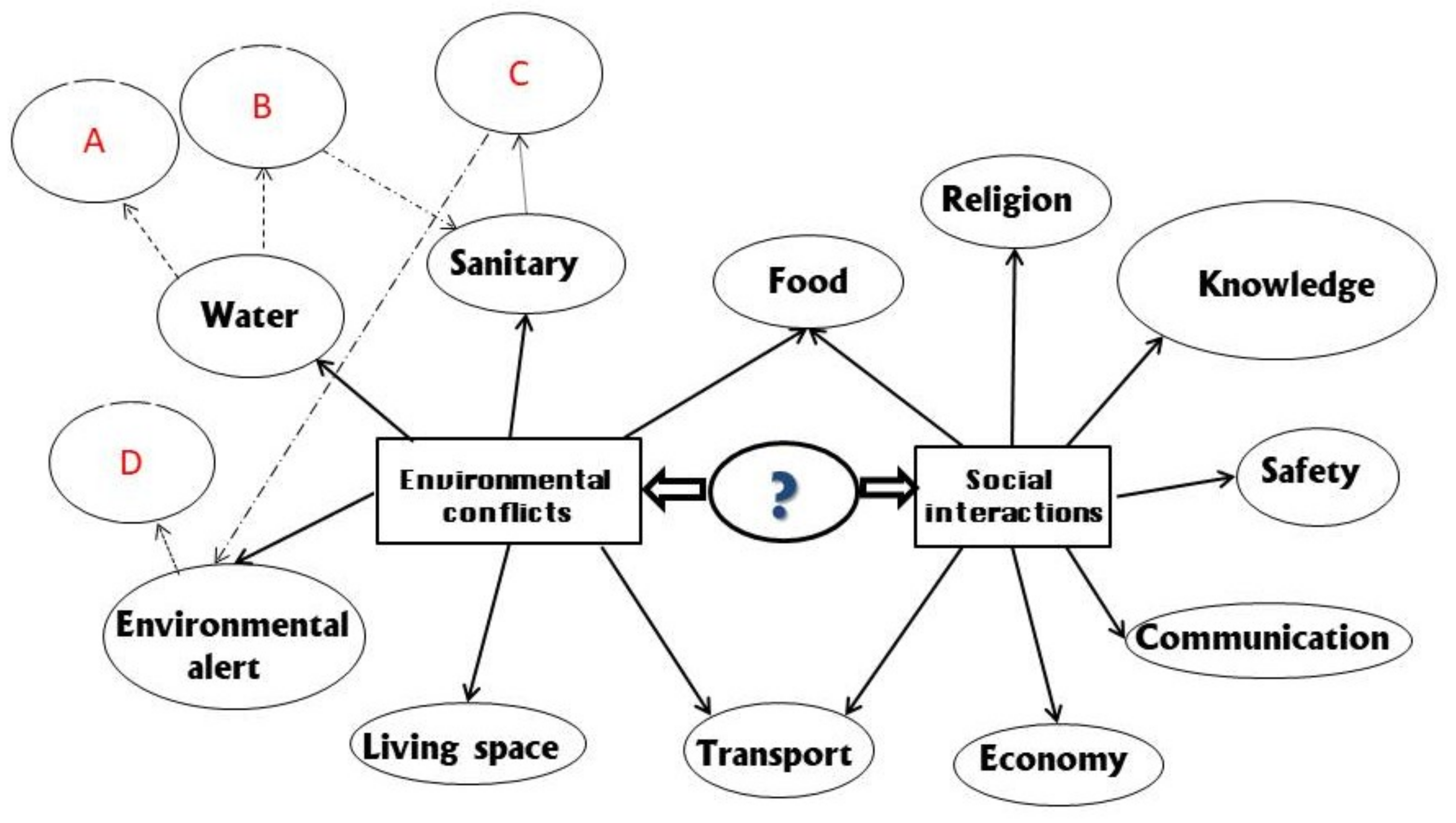

Figure 1 depicts the basic chart of the new classification introduced as an answer to the above-mentioned issues; it can be useful in the analysis of any selected area, or definite system or single element of UBH, represented by the central square with the question mark (?) in the chart.

The chart considers eleven functions, each of which generates the creation of correspondent caved artifacts. Four of them are connected to the management of environmental conflicts: sanitary, water, environmental alert (i.e., spaces placed in the underground level as an effect of the violation of natural elements) and living space. Five are connected to the management of social interactions: religion, knowledge, safety, communication and economy. Two are connected to both environmental and social issues: food and transport.

The chart allows the reconstruction of all the most important transformation processes undergone by the case-studies under evaluation. In

Figure 1, we introduce a graphic simulation of the analysis of a typical case-study by adopting the new classification, and carrying on a dynamic evaluation of its transformations during the considered period. In the given example, the artifact named B, built to manage an environmental conflict linked to water management was then transformed into an artifact dedicated to a sanitary function named C and, finally, was absorbed underground since it had been caved in an area exposed to environmental risks (perhaps unknown at the time and that can now be used to prevent similar risks for future plans).

The reconstruction of the historical dynamics affecting UBH given by

Figure 1, not only allow a better comprehension single case studies (i.e, selected geographical areas or single functions) but can also support comparative analysis among homogeneous systems of UBH (i.e., different political regions or geographical plateaus). The final result is the representation of the role played by the underground in supporting aboveground urban and rural development in the selected case studies. That being said, this approach can also be used as a starting point for additional actions concerning UBH. In fact, it can be the preparatory phase for both the evaluation of the effectiveness of the narrative role within valorization processes possibly already carried out and, also, support future actions in this direction. For these additional steps, a new chart for the classification of the level of reuse for UBH was introduced by the author.

Four different levels of reuse have been recognized:

Re-inventing cultural heritage: interpretation of historical functions, restoration, fruition as a cultural site (e.g., installations of technological instruments to communicate underground culture, reconstruction of underground life, etc.).

Re-introducing old functions: the historical sites restored and used again according to new parameters (e.g., productive spaces with the adoption of contemporary hygienic and security standards).

Re-interpreting historical spaces: the sites are restored, and new functions are allocated but the communicative role is preserved (e.g., shops, hotels, restaurants, urban facilities in pre-existent underground spaces).

Re-building: new caved artifacts are built with the adoption of the historical negative building culture (e.g., duplication of the original cave to allow fruition in case of maximum danger or vulnerability of the original one).

The above described methodological approach has already been successfully used in several analyses concerning either a single case-study, or to allow for the comparative analysis of different geographical areas. The latter is the case of a comparative study between underground settlements in Southern Italy and the Loess Plateau yaodongs in China. In that case, this methodological approach underlined how those cave settlements, born as a common answer to the same natural and social obstacles, albeit in different historical, cultural and political contexts, are now at the core of projects that reflect substantial differences in approaches to cultural heritage and sustainable urban and rural development [

12]. In addition, the metropolitan areas of Naples (Italy) and Saitama (Japan) are under analysis using the same method, in the project entitled “Damage assessment and conservation of underground space as valuable resources for human activities use in Italy and Japan” [

13]. The UBH approach is also the most innovative Italian contribution to the COST platform “Underground Built Heritage as a Driver for Community Valorization” [

14] which aims to support and strengthen common experiences in the use and valorization in selected case-studies which include: Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia. The present paper is dedicated to the case-study of Sassi in Matera.

3. Matera as a Case-Study

The site of the Sassi in Matera is located on the Murgia plateau whose geological character is strongly represented by gorges with internal natural caves (

Figure 2). It originates from a troglodyte village and is considered to be one of the first human settlements in Italy [

15]. The construction of this underground settlement reflects the progressive transformation of natural caves into closed caves, and then into

lamiones (the local name for caved spaces with external buildings). The various levels of these single dwellings over time created an urban landscape of underground dwellings and cisterns, the complexity of which can only be fully appreciated when observed in cross-section. These caves are located in a plateau district (Murgia) with a very long history testified by significant archaeologic rests which can be included in UBH as well. The plateau has been inhabited since Paleolithic times, as attested to by the recent rediscovery in a cave of the “man from Altamura”, the concretionary rests of a Homo neanderthal who lived in that area between 130,000 and 180,000 years ago [

16]. It passed through the Neolithic period [

17], as came out from several archeological rediscoveries and it has been continuously inhabited since then. In the year 1000, Basilian monks from Anatolia and Syria brought their culture to the area: the resulting cave churches in Southern Italy are perhaps the most striking examples of this influence [

18].

The demographic rise and the socio-economic decline of the area turned these dwellings into the socio-environmental disaster described in 1945 by Carlo Levi in his work “Cristo si è fermato ad Eboli” (Christ stopped at Eboli) [

19]. Following the success of this book and much consequent political pressure, Sassi became the tangible symbol of the gap between Northern and Southern Italy, between urban and rural sanitary life styles. The location underground of the city center itself was considered to be incompatible with politically accepted residential facilities in such a way that “level 0” was assumed to be the demarcation line between a politically correct approach to urban development and an unacceptable one.

The

Risananento (Restoration) of Sassi in Matera was part of a complex national program which included rational organization of rural areas, rural villages’ sanitation and public investments in Southern Italy in order to support its economy and population. The Prime Minister Alcide de Gasperi, after his election in 1948, visited the Matera city center and founded an inter-ministerial committee, under the responsibility of Emilio Colombo, whose goal was the definitive solution of the social and economic problem of Sassi, but with a conservative approach [

20]. According to these guidelines, on the 17th of May 1952, the Special Law for the Sanitation of Sassi n. 619 [

21] was approved and gave life to two potentially different parallel actions: on the one hand, the acceleration of the evacuation and the construction of the new vertical sanitary city in the suburbs of the historical center and, on the other hand, the idea of planning actions for the continuity in use and for the preservation, enhancement and valorization of the caved village as a masterpiece of local urban history. The application of this double approach was not easy or popular and, in the end, operative actions went in a different direction: in spite of the perceived value of the historical troglodyte village in terms of cultural heritage, it seemed impossible to upgrade and improve the performance of those artifacts as a living space. This assessment was the basis, in 1965, of the proposal n.1542 [

22] which planned the definitive abandonment of Sassi di Matera, definitely ruled in 1967 (Law n. 126) [

23] with the inclusion of most of them in the public property list.

About ten years later, in 1986, the conservation and restoration of Sassi were ruled by the national Law n. 771 which transferred the property to Matera’s municipality [

24]. On the basis of this new regulation, Matera’s civil council started a complex program of sub-concession for the use of Sassi on the basis of a biennial planning.

From the very beginning it was evident that all the actions planned for the valorization of Sassi’s cultural value had to face the effects of gentrification. The problem of the loss of the immaterial value of Sassi was already evident during the debate, which led to the inscription of the historical site in the UNESCO list in 1993, and this topic has always been at the core of all the projects carried on since then, mostly addressed towards the recreation of the historical rupestrian habitat, the essence of the UNESCO site.

Indeed, the site of Sassi in Matera, since its dismissal as a living space, has been, at the same time, a reference point for the study of the sustainable reuse of historical caved buildings and the valorization of the historical city center, as well as the perfect archetype for historical city centers affected by deep gentrification. This risk, as well as the actions to be carried out to face it, have been at the core of several studies by the architect Pietro Laureano, who has studied and supported all the steps of the post-dismissal history of Matera. Laureano wrote the proposal for the inscription in the UNESCO list in 1993, and for the very first time methodologically inscribed the troglodyte style within a larger approach to sustainable architecture. Furthermore, he supported Matera’s application for 2019 European Capital of Culture; and promoted the ARS Excavandi exposition for a worldwide celebration of Matera. Throughout his professional activity, Laureano focused on the unicity of the settlement of Matera and has always emphasized the necessity to preserve the primary use, or its memory, within reconversion processes to maintain the legacy of the city, also in consideration of the role played by the Southern Italian city within the Mediterranean underground scenario [

25,

26,

27].

The site of Matera’s Sassi is today at the core of a complex underground based rural economy and is included in the Matera’s Murgia Natural Park for the preservation and valorization of its historical and natural cultural heritage. Notwithstanding the fact that cultural tourism has become more lucrative as a result of the successful transformation of dismissed private houses into public spaces for tourism, the area is undeniably flourishing with lasting rural traditions linked to underground spaces: olive oil production in underground factories, typical bakeries in underground ovens, vines and cheese in underground canteens. Matera is also successfully implementing best practices in architecture by adapting dismissed houses once again to residential in order to invert the gentrification process.

The conservation and valorization process of Sassi was based on the reinterpretation of historical underground spaces; this transformation was ruled by Italian Special Law n. 771/86 [

24], which managed private and public involvement in the process of re-interpretation of historical spaces.

Sassi is the name given to the urban caved settlement located in two different complexes of troglodyte architecture excavated within two different karst valleys: Sasso Barisano and Sasso Caveoso. But Sassi in Matera (40°40′11.39″N, 16°35′50.03″E) is not an isolated example of a village born and developed as an effect of the negative building culture. It is, instead, the best known and most celebrated case of a diffuse Southern Italian urban development style geared towards the maximization of environmental opportunities, and the minimization of climatic and social linkages thanks to the application of a singular building technique. This urban development approach was historically developed in the area across Puglia and Basilicata, all along the Murge’s Plateau, giving shape to a diffuse Mediterranean [

28,

29] system whose extension and cultural identity are at the core of the multidisciplinary project “I sottosuoli antropici meridionali (Urban Undergrounds in Southern Italy)” [

30,

31,

32].

3.1. UBH in Matera

The methodology adopted for the study of the actions aimed at the valorization and enhancement of UBH in Matera is based on the application of the given classification to the corresponding caved elements and the analysis of the levels of reuse accomplished; both material and immaterial heritage is considered in the process.

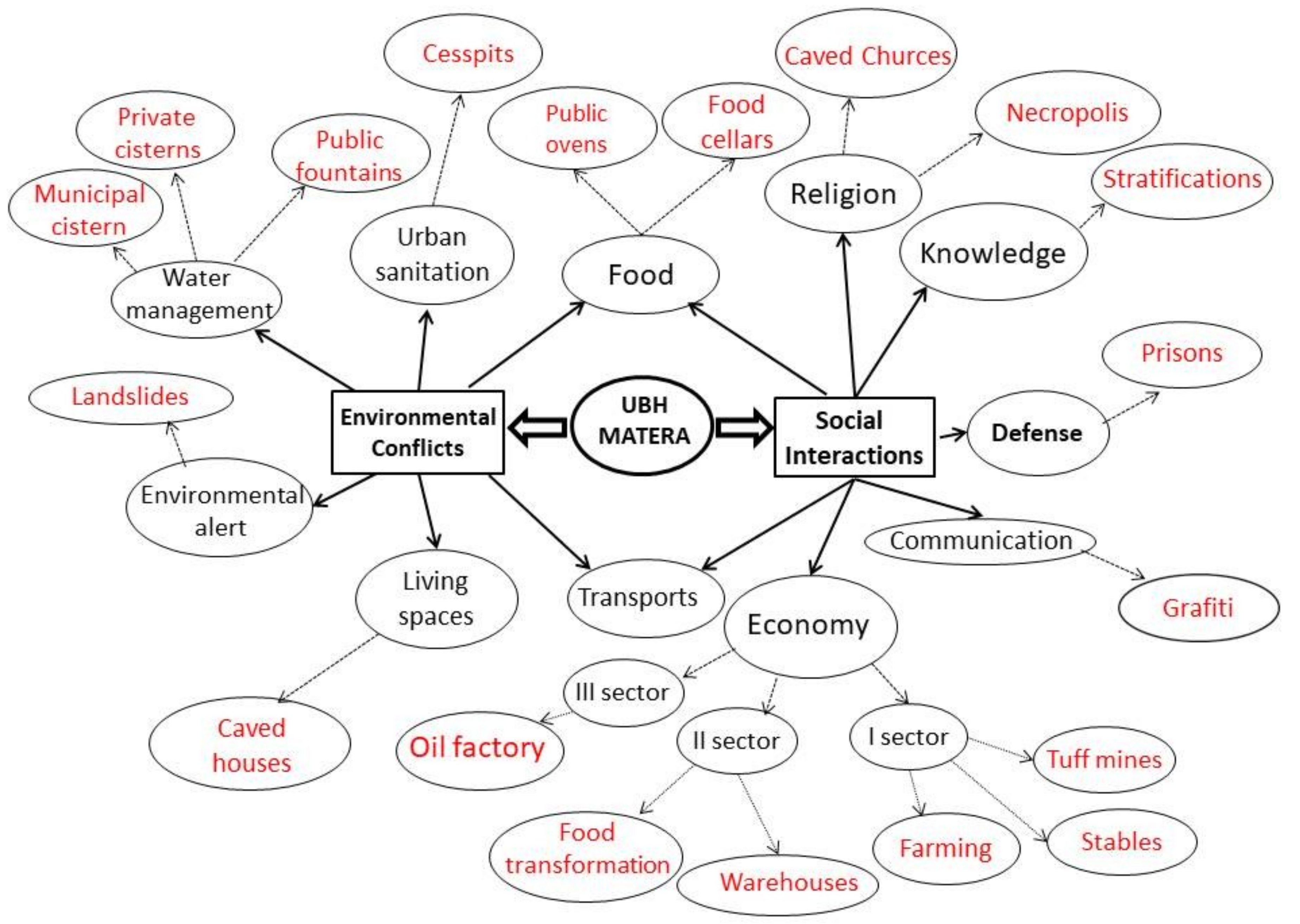

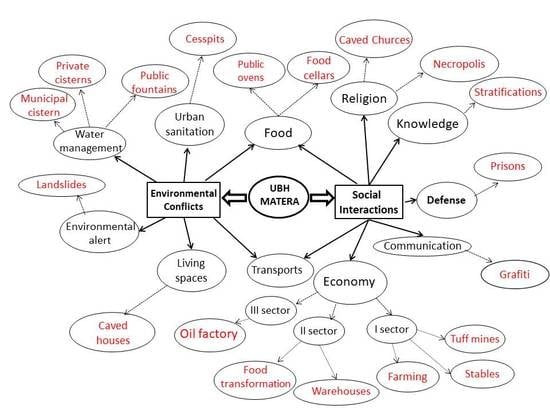

The functional classification of Matera’s underground space reveals that 10 urban functions have been historically managed in the underground, at private and public level (

Figure 3). In the Sassi district, in fact, there are elements of UBH that express solutions to four different types of environmental conflicts (urban sanitation, water management, warning and living space), five types of social interaction problems (religion, knowledge, defense and economy) and one type belonging to both categories (food).

With the exception of a transport function, which can be itself considered as the evidence of an absence of investment in the direction of sustainable planning in this specific sector, all the functions are represented for Sassi to be considered to be an icon of negative building culture. Underground was the place selected for urban development itself, and nowadays the stability of the caved city is a perfect instrument for monitoring the state of conservation of the local karst environment. Water has always been managed underground as well; sometimes giving shape to private water pools which completed the urban scenario, sometimes hosting public cisterns, sometimes feeding public fountains. Further, the historical space dedicated to food is mostly caved, both at the private and public level: bread ovens, deposits, food and wine canteens supporting aboveground daily life and allowing for the rational consumption of products for family use. With reference to religious issues, more than 150 churches were built underground by Basilian monks and diffuse countryside cemeteries can be found. All castles had underground prisons that reflected the political and social conflicts occurring on the Plateau. Underground graffiti is very common and used for communication. Last but not the least, the local rural economy was based on the use of underground space: tuff caves supported the edification of aboveground building, caves were used as stables and for pigeon breeding, and as a recovery for local agricultural equipment. Local manufactures also used underground spaces and over 150 oil factories were located in this area since oil was the most important commodity for the local economy even if, surprisingly, oil produced underground was never a food resource but was produced to provide burning oil for energy and used in soap and wool manufacturing [

33]. Caved spaces were also used for the production and the conservation of medicines: local pharmacies were cut into the rock to preserve the quality of dried wild herbs, brewed and mixed by local monks.

Basically, all of the Plateau’s history is written in underground layers: each one can be considered as a page of a book that recounts history through time and where the last page represents the deepest layer and most ancient of times back to the era of dinosaurs, as the rediscovery of their footprints in the area have proven [

34].

3.2. RE-USE in Matera

The approach to the study of reuse in Matera is based on the application of the given chart with reference to only three different levels (Reinventing, reintroducing and reinterpreting) because, as concluded by recent research, rebuilding has never been practiced in the Sassi district [

12]. The starting point of the study was an analysis of the most significant financed projects outlined in

Figure 4.

In the first column, the functional classification given to the UBH elements at the core of the projects; in the second, the critical points connected to their reuse, and in the third the actions carried out to overcome them. In the last column are the titles of the projects. In the next paragraphs, different levels of reuse are examined in detail on the basis of the integrations that resulted from a recent fieldwork research.

3.3. Re-Inventing

Reinventing is the most conservative approach, as well as the most appropriate one in the case of the enhancement of unique artifacts where maximum protection of the original shape is required. In Matera there is a wide range of sites which can be included in this group, responding to several historical functions managed in the past, but also presenting different critical issues to be overcome during the valorization processes. The natural character of UBH of Matera has, at times, motivated also the reinvention of selected abandoned caves once used as a living space:

Casa Grotta di Vico Solitario, for example, reproduces, for dissemination purposes, a former private house with the inclusion of the original equipment and with particular attention to its dual purpose (house-stable). Also the most important sections of diffuse networks have been reinvented for visitors: the

Palombaro, the municipal pool historically used for water management, is one of the most visited sites of Matera thanks to the elevated path and the light equipment which emphasize this dismissed underground network. The dissemination of stratification planes is at the core of the Project ATA2018 whose aim is to support the invasive visit to Sassi’s path with information about underground layers. Reinventing underground ovens, once used to support the production of the typical bread of Matera, was implemented with the protection of the brand

pane di Matera (Matera’s traditional bread), the selection of raw materials to be used, and the competence area (Protected Geographical Indication, CE regulation 510/2006); the cultural value of Matera’s bread is promoted in a dedicated space within the

Ridola Museum which hosts a collection of the family wooden stamps used in public ovens by customers. Historical religious use of underground space in Matera gave shape to more than 150 rupestrian churches. Thanks to the Zétema foundation, extreme preservation with controlled access, monitored climate and light exposition and virtual tours has been carried out for the Crypt of Original Sin, the so called Sistine Chapel of the rupestrian world (

Figure 5).

3.4. Re-Introducing

Re-introducing old functions in Matera is not an easy process. The complete gentrification of the city center has been exasperated by the success of Matera as a touristic destination which caused a series of collateral effects on the real estate market and on the functional distribution of spaces in the city center.

On one hand, in fact, it caused a rise in market value of former Sassi which are currently quoted at an average of 1.738 E/m2, a much higher price compared to that of modern residential homes even when they require significant renovations. The price trend is also dynamic because of the potential of those spaces in the hospitality sector due to the newfound fame linked to the 2019 events.

On the other hand, the total absence of services for local citizens (resulting from the conversion of all traditional shops into tourist targeted retailers, restaurants, coffee shops etc.) transformed the city center in an unattractive location for local citizens. The trend is so exacerbated, that even former cisterns have been connected with the corresponding levels of living spaces and transformed into rooms or hotel facilities. With these premises, it is not surprising that even if sometimes private owners transformed former Sassi into private houses, very often owners used them as B&B for profit rather than as a personal home; incomes of these enterprises are invested in suburbs real estate opportunities. However, the most diffuse cases of the reintroduction of old functions with commemorative elements of historical use concern some retail shops and services. It is the case of restaurants which celebrate historical food suppliers with reproductions of pictures or the introduction of historical suppliers in the contemporary design (

Figure 6), or bread ovens which still produce traditional products.

3.5. Re-Interpreting

The reinterpretation of dismissed caves is very popular in Matera: the Sassi were transformed into public facilities, local commerce enterprises, shops, exhibit halls, hotels and B&Bs. In the reinterpretation of historical spaces the original function was emphasized, also with the reintroduction of historical equipment and suppliers.

One of the most famous examples of this category is

Casa Cava, a dismissed extracting cave transformed in 2011 by Enzo Viti into a multi-function space: an underground theatre, a lounge bar and an open space available for temporary exhibitions. The approach is not invasive and is a perfect example of “best practices in architecture”: materials used in the project harmoniously interact with the original ones without concealing them. The final result is an eclectic space which communicates old values connected to the negative building culture: a perfect mix of the diffused contemporary design based on the elaboration of Matera’s UBH [

35].

The reference to UBH is constant in Matera: caved restaurants, troglodyte bars and food suppliers are very popular. The underground location is emphasized by the internal design, recalled in the names of plates and beverages served and very often underground stratifications are visible under glass floors to allow an immersive underground experience as well. Often old pictures are displayed to offer a truly immersive experience into the past (

Figure 6).

However, the most significant and common reinterpretation of troglodyte spaces is connected to the accommodation market for tourists. Nowadays, in Matera, underground locations have added value and underground character seems to be a ‘must have’ linked to luxury and high-end accommodations. Data elaborated on the basis of a fieldwork research has confirmed that hypothesis. In fact, while accommodations listed by the Matera municipality classified as B&Bs (usually rather inexpensive solutions) are not the result of dismissed UBH reinterpretation, the situation is very different for the 36 hotels and 163 rooms listed that are derived from UBH and often classified as ‘charme hotels’.

In the investigated cases, which refer to the total population and not to a statistical sample, not only is the re-interpretation of the underground spaces a direct function of the official classification given to the corresponding structures (the deeper, the higher) but the contemporary troglodyte style is also at the core of marketing strategies, closely linked to the level of prices applied to services and to tourists’ positive feedbacks.

Evidence based on 36 hotels, showed that 21 (58%) are the result of a reinterpretation of UBH and that this percentage includes the highest rated accommodations. In fact, while the only five-star hotel in Matera (*****L), is the result of the reconversion of a complex of dismissed houses and cisterns into luxury suites (one with a private swimming pool on the terrace, and a beauty center), the only three two-star hotels (**Hotel) are not caved at all. When not caved, underground prisons are granted the role of representing UBH and in one case secret underground galleries were also transformed into spaces for special events. In Matera we can also find a four-star (****) ‘diffuse hotel’ which reinterprets the caved village and its life with open air yards connecting all the caved private rooms. The connection to UBH is always achieved when possible, sometimes even through the evocation of other functions of the class. In the case of a conventional four-star (****) hotel, for example, it takes its name from the spectacular view of a dismissed tuff cave complex today re-interpreted as a permanent and temporary exposition space as well as a stage for theatre representations.

In regard to the category of room rentals, the troglodyte factor is not only predominant but, in some instances, even extreme or artificially introduced. Of the 163 structures under analysis, 67 (41%) are the result of UBH re-interpretation; however, the study of the functional classification of the historical artifacts which originated the transformation showed that this percentage includes several different conditions. In fact, although most of the examined accommodations are the result of the renovation of dismissed Sassi once utilized as civil habitations, the research showed there is extreme pressure on this cultural resource. It appears that since underground locations are so popular with tourists, emphasis on this element is sometimes instrumental, extreme or even artificial. There are some cases where even dismissed cisterns were transformed into rooms with no windows at all or only skylights; in one case even a dismissed snow cellar was re-interpreted. Occasionally, concrete or brick hotels, as an answer to the rising demand for the troglodyte factor, are prone to advertising the few rooms that resulted from the transformation of dismissed canteens rather than their predominant above ground rooms. In 10 cases, the alluring reference to the underground world is merely the result of the use of bare tuff in the renovation but advertised as troglodyte style; in one case even a very common niche in a dividing wall was emphasized and wrongly labeled as being connected to UBH.

4. Discussion

The analysis of the three levels of reuse carried out in Matera reveals that, in the absence of a specific regulatory framework for the safeguard of UBH, local administrators and private enterprises are freely interpreting the troglodyte character, sometimes even in an unprejudiced manner in order to satisfy the rising demand for negative built accommodations and facilities. The current situation certainly calls for more attention to the preservation of the immaterial value of Sassi, a factor which is strictly connected to the knowledge of diversified historical functions of Sassi before their dismissal. This monitoring is addressed to both local institutions and professional planners which, at different levels, are charged with the safeguard, enhancement and valorization of UBH in Matera. Public institutions should be asked to reinforce their governance with the introduction of elements addressed to the preservation of the historical value of troglodyte character and its integrity; professionals should be called to ethically respect the cultural resource by adopting specific approaches to UBH within contemporary design. Since planning multi-level cultural sustainable reuse in negative built villages requires a specialized knowledge of the correspondent caved artefacts, with specific focus on the multiple, and sometimes stratified, historical functions, an interdisciplinary approach is highly recommended. In particular, an urban history approach could eventually be supported by the newly introduced classification for UBH and the reuse chart.

Matera is the European Capital of Culture in 2019 and throughout this year it will be at the center of the debate on the valorization of negative building culture, its historical value, its monitoring, assessment, enhancement and valorization. Matera 2019 represents an opportunity to reflect on the role of underground space within contemporary urban planning, in the respect of underground layers and as an answer to the current urban services demand. During 2019, several thematic events, exhibitions, conferences, books, articles and communication channels will focus on the role of Matera in the global contest of UBH; it will be the occasion to share expertise, to consolidate networks of scholars interested in the underground urban landscape and its value, at local and global level.

The application of the UBH classification and the reuse chart tested in Matera could support all of these processes by addressing actions for urban sustainable development, social inclusion and cultural heritage valorization in karstic habitats.

On a local basis, the newly introduced approach could be applied to other underground settlements, and to all artefacts included in the UBH classification at different stages of exploitation in order to establish preventive sustainable approach within future valorization processes. This can be a good opportunity for smaller, but not less interesting, Suothern Italian underground settlements such as Gravina, Ginosa, Laterza, Mottola, Massafra, Palagiano, Grottaglie and Palagianello, characterized by diffuse and extensive

troglodyte character but presently not completely monitored and valorized [

36].