Abstract

The perception of our heritage is based on sign-functions, which relate visual representations to cognitive types, allowing us to make perceptual judgements over physical objects. The recording of these types of assertions is paramount for the comprehension and analysis of our heritage. The article investigates a theoretical framework for the organization of information related to visual works on the basis of the identity and symbolic value of their single constituent elements. The framework developed is then used as a driver for the grounding of a new ontology called VIR (Visual Representation), constructed as an extension of CIDOC-CRM (CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model). VIR sustains the recording of statements about the different structural units and relationships of a visual representation, differentiating between object and interpretative act. The result, tested with data describing Byzantine and Renaissance artworks, presents solutions for describing symbols and meanings of iconographical objects, providing new clustering methods in relation to their constitutive elements, subjects or interpretations.

Keywords:

iconography; art history; ontology; CIDOC-CRM; semantic web; digital iconology; digital art history 1. Introduction

The recording of the information related to a heritage object is constructed throughout the registration of different media items (photo, video, text or 3D reconstruction), which function as an anchor and representative in digital space of the original object/phenomenon. The cataloguing, organisation and archiving of such information is of crucial importance, not only for their future retrieval, but also for exposing, revealing and integrating this set of information, as well as providing domain specialists with tools for clustering and organising them.

While text-based objects have received a great deal of attention during recent years, little work outside the machine learning domain has been made in regards to images. As a result, the work of normalisation and integration of visual information continues to rely on old paradigms and practices. Tools for the semi-automatic classification of a 2D/3D object, for finding duplicates in a collection or for assigning names to an artefact have been developed. Nevertheless, most of these projects did not spend very much time reflecting on the significance of a representation, and on which basis we classify and interpret them. For such reasons, it is essential to reflect on the relationships between reality, person and image, analysing and integrating overarching theories developed within semiotics, art history, digital humanities and information science. Following this objective, in this article we attempt to construct an inter-disciplinary framework of understanding in order to outline a theoretical model for meaning assignment to visual objects, as well as to construct an information model capable of recording it. The result is two-fold: from a conceptual point of view we outline a basic version of a theory of visual interpretation, while from a functional perspective, we construct a formal ontology for recording the image classification act.

We present in Section 2 the literature review related to the topic. Section 3 is dedicated to a brief presentation of the theory of meaning, embracing a short explanation of the how we can classify percepts and how we re-use information in order to assign meaning to the visual object. Section 4 presents the functional results of the theory, introducing the VIR (Visual Representation) ontology, a CIDOC-CRM (CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model) extension for recording information about visual representation. In Section 5 its application is discussed, followed by Section 6, where limitations of the current approach are presented.

2. Literature Review

One of the earliest approaches to the analysis and interlinking of both knowledge representation and iconographical art was made by D’Andrea and Ferrandino [1]. In the article, the authors attempted to map and reuse concepts from both CIDOC-CRM (CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model) and the D&S (Descriptions & Situations) extension of DOLCE, developed by Gangemi and Mika [2] in order to extract image meaning, using D&S to add an information layer about the context and state of affairs of a specific representation. While the work was quite promising, no further development has, unfortunately, been recorded.

Even if restricted to the Byzantine icons domain, the study of Tzouveli et al. [3] is worth citing as one of the first and more complete works in the field. The authors used fuzzy description logic to determine features in Byzantine icons and map those features to an OWL (Ontology Web Language) ontology. However, the features identified are just labels, and no structural or identity criteria are provided in order to understand and aggregate pictures. Moreover, the study, as the authors highlight, is limited to Byzantine imagery, therefore limiting the applicability to more complex scenarios.

Also interesting is the solution developed by De Luca et al. [4] during the analysis and documentation of the tomb of Emperor Qianlong in China. The initial investigation revealed that the engravings and iconographies of the tomb were arranged in order to reflect the Buddhist Tibetan funerary ritual; their layout and spatial position reflects the deposit of religious text within a stupa. To visually show this kind of relationship, a virtual stupa was created and put in a relationship with the final 3D model, in order to allow the interlinking between spatial elements and their conceptual counterparts. Additionally, a graph-like interface was created in order to browse the conceptual elements linked to the physical representation. While not using formal representation methods, this solution demonstrates the possibility given by a semantic description of iconographical features. However, even in this case, no identity criteria for recognising and aggregating pictures were provided.

Probably the most comprehensive solution is the one developed by the Fototeca Zeri in Bologna [5,6,7] for the PHAROS (International Consortium of Photo Archives) project [8]. While exposing the Zeri Photo, the authors developed two ontologies (F Entry Ontology and OA ontology) to map data coming from the two Italian standards developed by the ICCD (Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione, or Central Institute for the Cataloguing and Documentation), the Scheda F (Scheda di Fotografia, or Photography Entry in English) and Scheda OA (Scheda Opera d’Arte, or Work of Art Entry in English). The two ontologies were mapped with CIDOC-CRM as well as HiCO (historical context ontology) [9], PRO (publishing roles ontology) [10] and FaBIO (FRBR-aligned bibliographic ontology) [11], which guarantees the possibility of adding information related to, respectively, the provenance of assertions, the roles of the agents dealing with the artworks and the position of the object in relation to the FRBR (functional requirements for bibliographic records) model. Moreover, thanks to an extension and mapping between HiCO and PROV-O (PROVenance ontology), the ontology allows the recording of information in regard to the influence between works of art. This work is excellent and touches diverse needs in the art history community, but it does not take into account a description of the features and attributes, which would greatly help in the retrieval and aggregation of visual items.

3. Ontological Framework

3.1. Introduction

The representation of an object can be of different form and nature, can underline one specific aspect or feature, can have different degrees of faithfulness and can use different grammars to encode the same type of information. The purpose of these representations is not to display and interact with a simulacrum of the heritage object, but to actually use them as instrument of analysis, to make statements about the world through them, to find metrics to compare objects, study their behaviour, subdivide them into units, reconstruct their holes, re-define their existence, put them into their historical context, study how they interact with their ecology and how they shape it, or how they could be and how they were not. Representations of this type are not treated as simple depictions, but are instrumental to the knowledge we derive from our past, because we have the tendency to assign them the status of digital counterparts of heritage objects.

For these reasons, it is essential to understand how we assign meaning to them, as well as how we identify and differentiate between diverse visual compositions. In order to answer this question, we are obliged to start analysing the perceptual process, and, specifically, the interpretation of a percept, which heavily relies on the act of recognition, classification and reference of the sense data to a model using a specific visual code.

3.2. Cognitive Type

Ontologically speaking, the perceptual challenge revolves around two main subjects: the existence and the identity of a visual representation. It is necessary to define the subject of the percept, as well as to understand the mechanism used for the percept to be referenced as an instance of a class.

We argue that the interpretation of a visual message requires the connection of the sense data to a model using a specific visual code. The sense data themselves are selected portions of the continuum of reality, which Floridi [12], building on the work of MacKay [13] and Bateson [14], calls a datum.

The recognition and categorisation of a datum is achieved by the relation of the datum to a reference type, using a schema to mediate between the concept and the manifold of the intuition. Eco [15] suggested that to comprehend this process, we should start examining how we classify the unknown. We will delve deep into his thesis, identifying the nuclear elements which enable us to build a shared understanding of our visual reality. For such reason, it is of paramount importance to first introduce, analyse and explain Eco’s theory. Eco asked himself, and his readers, how we would be able to interpret and socially talk about something if we were to see it for the first time. He proposes a thought experiment using the Aztecs’ first encounter with the Spanish knights. During this occasion, the Aztecs were faced with an entirely new animal, mounted by individuals completely covered by metal plates.

“Oriented therefore by a system of previous knowledge but trying to coordinate it with what they were seeing, they must have soon worked out a perceptual judgment. An animal has appeared before us that seems like a deer but isn’t. Likewise, they must not have thought that each Spaniard was riding an animal of a different species, even though the horses brought by the men of Cortes had diverse coats. They must therefore have got a certain idea of that animal, which at first they called macatl, which is the word they used not only for deer but for all quadrupeds in general”.[15]

What is interesting from this passage is not just the recognition of the nature of a horse as an animal, but the difficulties that such collective recognition impose on the exchanges between the messengers and the emperor. The messengers integrated their description with pictograms and performances, aiming to describe not only the form of this new animal, but also its behaviour. After listening to them, the emperor had formed an idea of the macatl his messengers were talking about, but it would probably have been different from the one in the minds of his messengers. Nonetheless, it was accurate enough to allow Montezuma to talk about a macatl, to be able to recognise one and differentiate it from the Spaniard riding it. Moreover, he was probably able to recognise not only the single macatl, but the entirety of them as a single species, even if they had differences in colours, size or carried armour. Gradually, he was able to acquire more and more knowledge about this macatl, about its usefulness in battle as well as its behaviour and origin (earthly or divine for example). Finally, the Aztec started using a specific word for it, modifying the Spanish word caballo into cauayo or kawayo. The story above presents an interesting perspective of the perceptual process, specifically of the recognition and categorisation of new objects, and it allows us to see how, on the basis of the object’s characteristics, we produce an idea of a percept. In his analysis, Eco [15] calls this idea cognitive type (CT). In this case, the CT would be the concept that an Aztec used to recognise a horse as an exemplar of its kind. After having seen some horses, the Aztec would have constructed a morphological schema of it, which comprised not only an image-like concept of the horse, but included its peculiar characteristics such as the neigh, its motions, its capability of being mounted and perhaps even the smell. These elements are the base used for creating the CT of the horse, which appears to be then a multi-sensory idea of what we see.

For many readers, this concept will resemble that of the prototype [16,17], but the difference is in their nature. The prototype is an instance of a class which is seen by a cultural group as the one that best represents the class itself. The CT instead works within the primary semiosis field, assessing the membership to a specific category based on perceived characteristics, and it is not an instance, but merely an idea of the nuclear traits. The prototype is an instance of a class which we assume best covers the characteristics of that class, while the CT is nothing other than the idea that allows us to define the membership itself, more closely to an underlying grammar for the construction of the class than to another concept.

3.3. Semantic Marks

Unfortunately, Eco does not explain in detail how cognitive types do work, or how we can use this grammar to relate sense data to a semantic and conceptual model in order to achieve a similarity-based recognition. Therefore, it is essential to build up from his theory and define how we construct the identity of an element, correlating visual data to nuclear characteristics. In order to analyse this process, we introduce the concept of the semantic mark (SM). We define a SM as internal encoded functions which help classify external stimuli and discern their nature. SMs are sense based and help classify the perceptual experience by correlating perceived signals to the CT of a situation, and to the CT of a physical thing. Both SMs and CTs are based on equivalence-based criteria between the percept and a situation/object which are similar to. Further recognitions are achieved by a similarity-based degree of the newly perceived SMs and the SMs that characterise a previously constructed CT. SMs function as attributes of the identity of a percept. The number of signals received by the senses can be numerous, but the chosen ones that are used for the identification are fewer, and they present themselves as constituents of a perceptual manifestation. While a SM can be seen as another type of sign, it is instead an encoding of the percept on the basis of a classification, which reuses our experience and social ground for determining the significance of our reality.

Having outlined the gist of it, it is best to start formulating a formal analysis, because only through their definition can we comprehend their role in the perceptual process. A SM is the result of a semiotic process which works with three components:

- At least one signal.

- A situation.

- An object.

The very first component is the signal, which is an external stimulus, a datum, identified on the basis of its difference and its form. We will flatten its definition, for a functional purpose, using logic, as:

Definition 1.

∀signal(x) → ∀x.((hasDimension(x, N) ∧ isPartOf(x, System)) ∧ different(x, Surrounding)), where x is the signal, which is identified by a dimension (N) in a specific system (could be a specific projection system as well as a topological relationship). The identity of the signal is, moreover, defined by its differences from the surrounding area, because it is exactly this element which grounds its identification into a single unit.

Having outlined the criteria for the identification of a signal, we should look to the other components of a SM, situation and object, in order to understand how it is interpreted. The notion of a situation is quite fuzzy. Situation theory and its semantics have been the subject of many academic debates [18,19,20,21] in the last thirty years. Many have written on the topic, but there is no real agreement in the community on what exactly is and how to define a situation. Nonetheless, we used some of the elements discussed in those debates to build our definition of a situation (s) as:

Definition 2.

sdef = {R, a1, …, an, ωx}, where R is the relationship perceived by a viewer between a set of physical entities (a1,…,an) in a specific space-time volume (ω), a portion of the space-time continuum. The types of relationship (R) between the entities can be of diverse nature, such as mereotopological or temporal (for a better account of these, see the work of Smith [22,23], Varzi [24] and Freksa [25]). Situations, however, while carrying their own identity, are not unique temporal states that need to be determined every time, but can be approximated as an instance of a situation type (where the situation type is just the closest logical counterpart of the CT of a situation, used here to determine its membership function), which is a prototypical situation we have experience of, and helps us determine a specific perspective or a behavioural pattern to follow.

The relation between a situation s and a situation type S is a degree of membership of the elements of s in S where:

Definition 3.

A situation type S is a pair (S, m), where S is a set and m:S → [0,1] is the membership function. S is the universe of discourse, and for each s ∈ S the value m(s) is the grade of membership of s in (S, m). The function m = µ(A) is the membership function of the fuzzy set A = (S, m).

Using the same logical notation, we can define the relationships between a physical thing p and its type P, such as that an object is equivalent to the entirety of the relationships of a set of physical parts identified by the combination of specific materials over time and P is:

Definition 4.

A physical object type P is a pair (P, n) where P is a set, n:P → [0,1] is the membership function, and for each p ∈ P the value n(p) is the grade of membership of p in (P, n). The function n = µ(B) is the membership function of the fuzzy set B = (P, n).

As mentioned before, the resemblance is given by a degree of similarity. Therefore, the sets A and B, which are, respectively, the set of all the matching situations and the set of all the matching physical objects, which we can describe as:

Definition 5.

A = {s, µA(s) | s ∈ S}.

Definition 6.

B = {p, µB(p) | p ∈ P}.

should use a membership function type which takes as an input the value of a similarity-based degree calculation. However, similarity is not, as it is commonly understood, a juxtaposition between two anatomically similar elements, but a more complex phenomenon. Nevertheless, it is possible to map the correlation between elements in a multi-quality dimension, including, depending on the case, topological, feature, alignment or value information [26]. The value information is based on different qualitative criteria, such as material property, colour, size or reflectance. For example, two representations portraying two different subjects could be grouped together if both had a golden background, or if the objects portrayed had the same size; topological information relating the closeness of two or more objects in a specific space reference; a local space, such as a portrait where two dots stand in proximity to each other, or a geographical space, such a country or a town. Feature similarity implies the presence of a few distinctive features that are considered more salient than others by the viewer and are taken as a key for grouping some objects. This could be the case of wearing a hat with a feather or carrying a Latin cross. In both cases, we use these elements to say that two objects are similar. The alignment similarity indicates the likeness of one or multiple parts of an object in respect to one or multiple parts of another object. It implies the possibility of juxtaposing the two parts together. We will not provide an indication as to which membership function should be chosen (Gaussian distribution function, the sigmoid curve, quadratic and cubic polynomial curves etc.), because the methodology depends on what kind of similarity information is being taken into account. For a full account of the methods, refer to great commentary on the subject given by Timothy J. Ross [27]. At last, having determined that the relationship between situations is a physical thing and its CT (for functional purposes, logically expressed as type), we have all the elements for defining the semantic mark of an object, which we define as a tuple:

Definition 7.

SMx = {(Sigx,…, Sign) A,B}, where (Sigx,…, Sign) is the set of signals identified, A and B are, respectively, the fuzzy set of all the matching situations and the one of all the matching physical objects in respect to a set of signals which were used to contextualise the signal. We define a semantic mark as the result of a function which relates the signals to a situation and a physical thing to create denotative expressions that link the initial signals to specific cultural content. Following this definition, a CT can be defined as a set of semantic marks. The recognition of this set implies the attribution of the type.

3.4. The Reading of the Image

The use of semantic marks to construct the cognitive type of visual items can be further examined throughout the lenses of art history, a discipline which has closely studied the history of representations and has provided us with some of the finest thought on the subject, thanks to major works by Warburg, Panofsky, Gombrich, Arasse and other scholars. In doing so, we follow Eco’s suggestion that iconography and iconology can be considered a fully formed chapter of semiotics [28], as well as the thought of some other art historians who have noticed the congeniality of the analysis of Peirce and Saussure with the study of Riegl, Panofsky and Schapiro [29].

Furthermore, art historians have been studying the formalisation of visual cues, the creation of canons and models of depiction for quite some time, and they are also responsible for the formalisation of several resources used as a nomenclature system for artistic motifs and subjects.

Art historians have long been studying visual cultures and their inner traits, recognising their commonalities and nuances and linking those to social arena. One of the results was the possible identification of the author of an artwork on the basis of his figurative and stylistic features. An author, in fact, learns and develops specific traits or features during their apprenticeship in a workshop, or by merely examining or studying their predecessor’s works. The usage of a set of traits to depict a figure standardises compositions and features, creating a representational canon. One great example is Renaissance art. In this period, thanks mainly to a rediscovered sensibility for the Roman and Greek period, artists and patrons felt the need to have a standardised and understandable canon of images, an easy instrument with which to get inspired and follow the design and conception of new works of art [30]. While the need was, indeed, general, there were certain specific tasks, for instance, the representation of identifiable intangible concepts such as Love or Fortune, which benefited greatly from such formalisation. The illustration of these abstract ideas had to be done through the use of substitutes for the abstractions, such as symbols or personifications. The use of these visual devices as the embodiment of concepts and ideas, however, also fulfilled the communicative purpose of an image, providing the viewer with a possible reading of the scene. In order to do so, these figures needed to be acknowledged by a high number of people. Achieving such a goal required a figurative normalisation in accordance with specific models. It was bearing this prospect in mind that in the 16th century manuals like “Le imagini colla sposizione degli dei degli antichi” [31] and “Mythologiae sive explicationis fabularum” [32] started to appear. A major milestone in this direction was the publication of Ripa’s Iconologia [33] in 1593. This work covers over 1200 personifications, comprising an extensive collection of visual representation drawn from both classical and contemporary works of art. Ripa’s book reported on not only visual representations (added only in the 1603 edition) together with their designated meanings, but included detailed descriptions of how they should look and why they should be depicted in that way. The impact that Ripa’s Iconologia had on his contemporaries, as well as on artists in the later centuries, was remarkable, and started to lose its importance only with the advent of realism [34].

The impact of Ripa’s Iconologia was not only to be searched for standardisation of the features and poses for the recognition of depicted types, but also on the influence that those standardisations had on the Western-based vision of art. Art historians became used to employing a type-based thinking for their studies as well as heavily applied prescribed literary sources for their figurative reading; they finally become “hunters of prototype,” famously criticised for leaving matters there, and not exploring them further. While the hunting of the prototype has been seen as an infatuation, from which many, fortunately, have recovered, it also helped deliver a methodology which, even if criticised, has not yet found a real challenger or an alternative [35]. We are talking specifically about the work of Panofsky, which helped establish the discipline of art history as we know it now, and it helped investigate those visual cues that we use to identify representations.

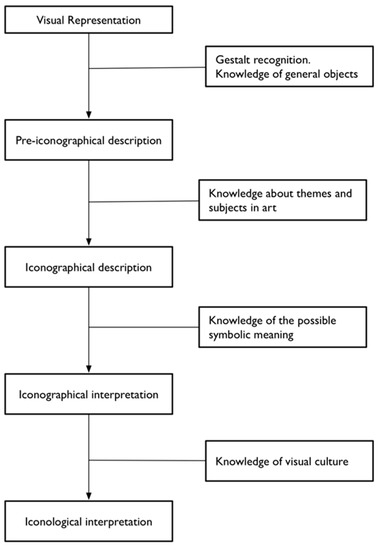

In his work, Panofsky [36] outlined a method for reading a work of art that required the distinction of an artwork in three layers:

- The primary or natural subject matter, which identifies pure forms such as a configuration of lines or representations of an object, which could be called the world of artistic motifs. The collection of these motifs pertains to the pre-iconographical description of a work of art.

- The secondary or conventional subject matter is the assignment of theme and concept to the composition of artistic motifs, which are recognised to be the carrier of a conventional (how specific themes and concepts are usually depicted in the visual arts) meaning. The subject(s) of a representation are identified in this layer, thanks to an iconographical analysis.

- The intrinsic meaning or content is the interpretation of “the work of art as a symptom of something else which expresses itself in a countless variety of other symptoms, and we interpret its compositional and iconographical features as more particularized evidence of this ‘something else’” [36]. The intrinsic meaning is defined by how cultural-historical developments are reflected in a representation, and such meaning is displayed independent of the will of the artist, who could be completely unaware of it. In a later stage, Panofsky called this phase the iconological interpretation.

Following his methodology, the signs that compose a representation are identified during the pre-iconographical phase through the identification of artistic motifs. This step was also identified by Barthes, who called this immediate visual impact, which defines the primary subject matter, the denoted meaning of an image, and the process it originates, denotation [37,38,39].

The second act of interpretation is the iconographical analysis, which requires more specialised knowledge and the use, in this case, of vocabularies of forms in order to describe the content of the image. These vocabularies do not have to be external resources, but they easily can be embedded in our knowledge repositories and inherited in a social arena (see Bourdieu [40] and Lemonnier [41] for a theoretical treatise on the subject). The recognition of the meaning of the image is based on identification of the diverse signs incorporated into the image, usually consisting of sets of attributes and characteristics. The combination of these attributes, such as objects, plants, animals or other icons/symbols, help identify a personification/character in a specific situation/narrative in a work of art. Attributes can also help identify certain qualities (kindness, rage etc.) of the depicted character, or his belonging to a distinct group (blacksmith, noble, saint etc.). The use and harmonisation of this combination have helped to create iconographical types and defined archetypical situations, providing tools for the identification of diverse types of representations [34,38]. Attributes can be seen as a subset of the semantic marks formalised in 3.3. In that case, it appears that iconographical types are nothing other than cognitive types we use for describing and communicating stances about our visual world.

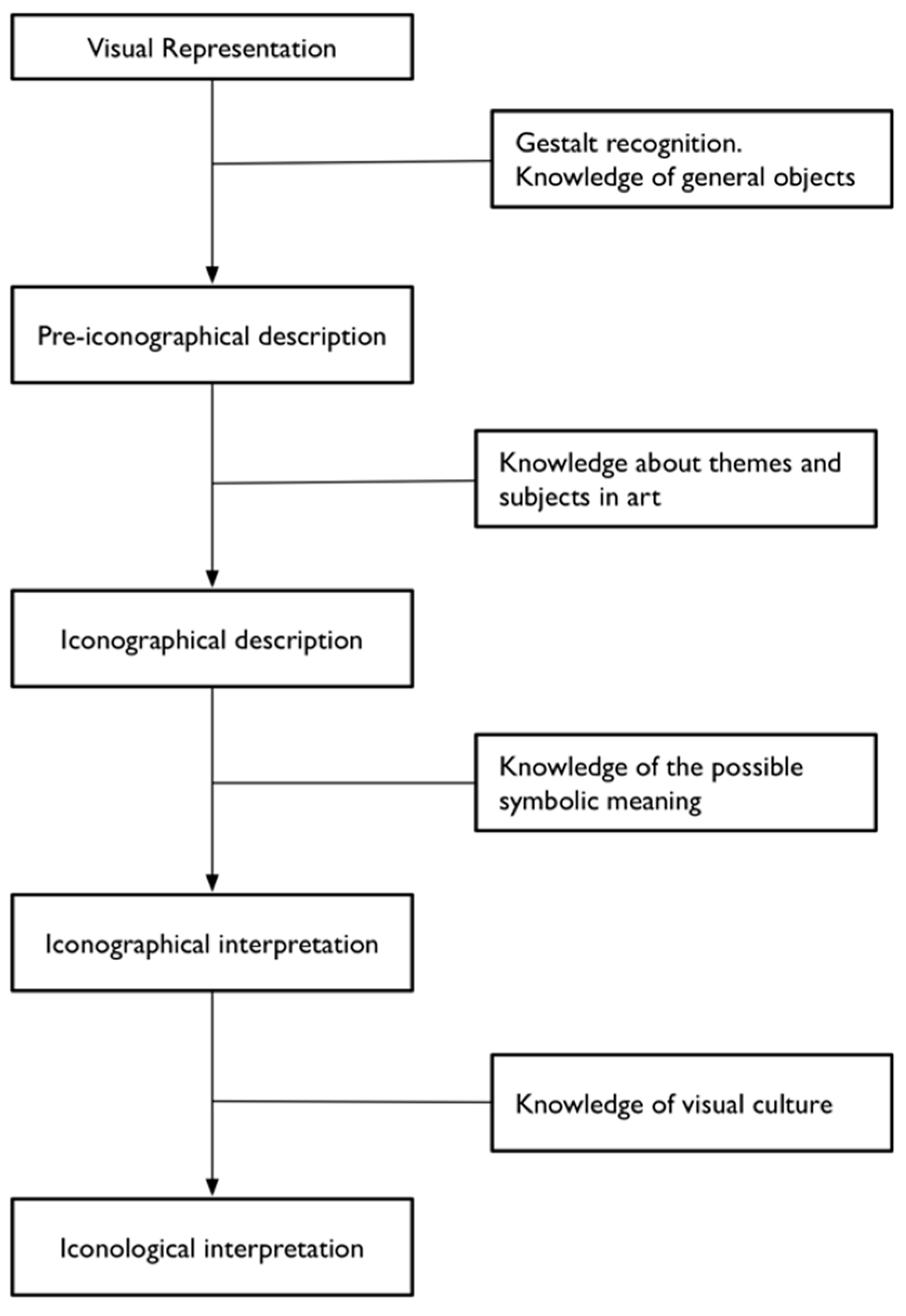

After the iconographical analysis, the methodology of Panofsky passes over to iconological analysis, which comprises the socio-historical interpretation of the symbolic value of the painting, which is part of a bigger cultural visual history and is not a conscious process for the author. The indeterminacy of these symbolic values created some significant issues in the art historical community, because sometimes the use of symbols was strongly driven by the author’s intention (as in 16th century Dutch art for example). In order to overcome these issues, and to stay true to the idea that an author can use symbolic representation consciously, we prefer to adopt the revised scheme of Van Straten (Figure 1) [34]. Van Straten does not challenge the first pre-iconographical phase of analysis, focused only on the identification of the artistic motifs such as lines and shapes, but he concentrates instead on identification of the secondary subject matter and the intrinsic meaning. The iconographical analysis is divided into iconographical description (second phase) and interpretation (third phase). The iconographical description is the analytical phase, where the subject of the representation is established (for example “Saint George and the Dragon”) but deeper meaning is not searched for. In this scheme, we can attribute an iconographical description to all works of art, in contrast with the analysis of Panofsky, which recognises the possibility of assigning a secondary subject matter only to a limited set of works of art (landscape, for example, could not be iconographically analysed).

Figure 1.

Van Staten’s division of the layers present in a work of art.

Iconographical interpretation examines the explicit use of symbols by the artist, and formalises the deeper meaning of a representation. One of the results of an iconographical interpretation is the decoding of symbols and the formalisation of what they express. We can envision the re-use of the codification of these signs to computationally track and analyse them, grounding their use in time and space, and discovering how they originate, evolve and spread across communities.

The fourth and final step of the analysis is iconological interpretation, which deals with those symbolic values that are not explicitly intended by the artist, and are part of the visual culture of the time.

These symbolic values can be analysed historically and ethnographically, and not only from an art historian’s perspective. Iconological interpretation adds a new level of meaning to a representation, the connoted meaning. If the denoted meaning previously introduced is about the object as expressed by form, the connotation is an interpretation on the basis of a socio-historical analysis of the symbols of an image [37,39]. The codification, description and tracking of connotative references between visual and conceptual objects is another important aspect to track, because it is even more socially grounded than explicit reference. Integration of the study of symbolic values in visual images could help us make sense of how we use semantic marks to classify reality, and how it does change on the basis of the context in which the visual classification takes place.

It is clear that Panofsky’s methodology, and the revised version proposed by Van Straten, can be easily integrated with the theory of cognitive type and our addendum about semantic marks. The two methods should be then seen as complementary (Table 1). In fact, semantic marks help us formalise the relationship between a percept and its interpretation, while Panofsky’s methodology provides a path for the reading of a work of art, defining a way to take into account the propositional assumptions of a viewer in relation to a visual representation. The division of the assumptions in layers of meaning is hypothetical, and just a formal way of proposing a reading, which Panofsky uses in his attempt to eliminate subjective distortions. These distortions are, however, always present in the understanding of a visual work, and do not depend on the work itself, but the situation and social context of the assessment, as proven in Section 3.3. A non-Western centred approach to classification would provide different readings and understanding, and that is why it is important to clarify when and how the interpretation of visual signs take place.

Table 1.

Correspondence between subject matter and act of interpretation.

4. Ontology

4.1. Introduction

The theory outlined in Section 3 will be used as a backbone for developing an ontology for the description of visual representations, and is going to be regarded as its main conceptualisation. Developing an ontology, in fact, means primarily relying on a clear commitment to a particular conceptualisation of the world, and to reflecting this commitment in an information artefact which approximates the intended model. We translated the existential and identity commitments outlined in Section 3 to construct an extension of CIDOC-CRM called VIR: visual representation1.

The name is, of course, significant, because the scope of the ontology is the formalisation of the relationships between the visual representations and symbols that characterise a single artwork or are distinctive of a social arena. VIR is grounded on the semiotic distinction between expression and content, and introduces class and properties for annotating pictorial elements that compose visual works and their denoted/connoted conceptual elements.

4.2. Case Studies and Problems

The objective of the formal ontology was the recording of statements about a series of wall paintings present in the church of Panagia (Mother of God) Phorbiotissa, commonly known as Asinou, in Cyprus.

The church, built in the picturesque setting of the lower Troodos Mountain in central Cyprus, around twenty kilometres from Nicosia, is richly decorated and displays a wide variety of frescoes ranging from twelfth (foundation) to the early seventeenth century. It has been recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1985, together with nine other richly decorated rural churches and monasteries in the area, which have been grouped by UNESCO as the “Troodos Painted Churches Group” [42,43].

The initial core of the ontology was later refined while analysing the dataset of the photographic archive of the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies. The archive of the centre holds a collection of around 250,000 photographic prints, focusing mainly on the Italian art, especially painting and drawing, of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance from 1250 to 1600.

During the analysis and description of the visual information presented in our case studies, we quickly noticed that iconographic representations are dynamic objects that evolve over time. In order to easily demonstrate this to a wider public, we chose to focus, in both case studies, on a widely known iconographical character: Saint George.

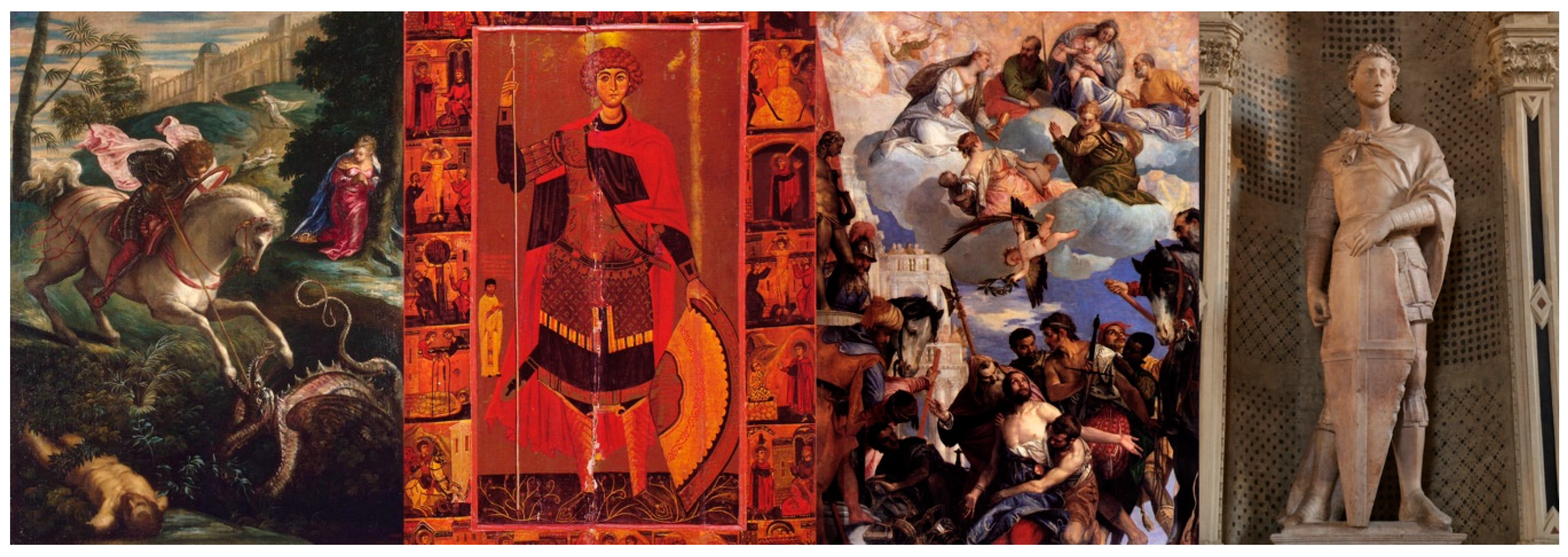

The depictions of the saint are quite heterogeneous, and display him in very diverse situations. Spanning from the sixth century to this very day, representations of Saint George have depicted him as a haloed, beardless knight in different poses and scenes. Initially painted standing in his military attire, he was later represented in various scenes such as the laceration on the wheel, the resurrection of the dead and the destruction of idols, which are strongly linked to his biography and his legends [44]. While, currently, the most widely known iconographical type is surely “Saint George and the dragon,” which portrays the saint slaying a dragon and saving a princess, it was only from the 10th century that he started to be represented on a horseback killing a dragon (Figure 2 for a small overview of Saint George iconography).

Figure 2.

Diverse representations of Saint George. From right to left: (1) Saint George and the Dragon—Tintoretto, 1560. National Gallery, London. (2) Saint George and scenes from his life—Anonymous, first half of the 13th century. Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai. (3) The Martyrdom of Saint George—Veronese, 1565c. Chiesa di San Giorgio in Braida, Verona. (4) Saint George—Donatello, 1415–17. Bargello Museum, Florence.

Initially, no princess was involved, other than in a unique case and in a very different role, in the church of Panagia tou Moutoulla, Cyprus, where the saint killed a crowned woman with the body of a snake [43]. It was only in the 12th century that the laceration on the wheel and the other torments started to be replaced by the rescue of the princess. The origin of this iconographical type can be traced back to a Georgian manuscript dated 11th century, and it is, indeed, in Georgia that we can detect the first representation of Saint George saving a princess from a dragon [45]. It is important to underline that the depiction of Saint George slaying a dragon does not have any privileged uniqueness, because several other characters were famously depicted killing a dragon [46]. Within Christian imagery, many saints slew a dragon. The most famous ones are St. Andrew, St. Matthew, St. Philippe and St. Michael. However, they are not the only privileged ones, and many more can be listed.

Representations of dragon slayers can be found in other mythologies. The small sculpture of Horus on horseback, for example, depicts a scene very similar to the one of Saint George slaying the dragon. This small sculpture portrays the Egyptian god Horus the moment before he stabbing the deity Setekh/Set, the Egyptian god of the desert, who adopted the form of a crocodile to escape his nephew [44]. Even restricting ourselves to the Christian imagery of Saint George, many are the works of art depicting the saint, comprising many different perspectives, stories, characters and stylistic choices. Only focusing, as is currently done in the visual classification domain, on description or annotation of the iconographical type (e.g., Saint George slaying the dragon) would result in the creation of an all-encompassing description which includes a wide range of different characters and variations.

It is clear that for each representation there are many possible variants, and simply classifying something as an instance of a specific iconographical type is not enough to characterise it and distinguish it from the network of similar depictions of the same type. The use of the same iconographical type does not imply the presence of the same character, nor the use of the same attributes and symbolic references. It is essential to describe each of these features in order to be able to cluster the representations on the basis of their characterising elements and their interconnections.

4.3. Recognition of a Representation

In order to classify the statements about our case studies, we introduced eight classes (Character, Iconographical Atom, Attribute, Representation, Personification, Visual Recognition, Verso and Recto) together with twenty properties. We will briefly introduce some of these classes, and then use a few examples to demonstrate their usefulness in the description and mapping of information about visual representations.

The very first step taken during the construction of the ontology was the introduction of a way to sustain new relationships between the physical and visual domain, declaring the new class IC1 Iconographical Atom. The substance of an Iconographical Atom is that of a physical feature, embracing an arrangement of forms/colours, which is seen by an agent as a vehicle of a representation. The identity of the class is given by the pure act of selecting a region of space as the content form of an expression. An Iconographical Atom does not represent anything in itself, but is the physical container we examine when we recognise a IC9 Representation. An Iconographical Atom is always the object of an interpretation, and the conceptual understanding of what it is depicted (the Representation) is the result of a recognition. Therefore, the Representation cannot exist elsewhere than in the conceptual domain, because it is the idea formed in the mind of the viewer when looking at the Iconographical Atom. For such reason, we define a Representation as the set of conceptual elements we use for associating the nuclear characteristics of a visual object with an Iconographical Atom.

If we had to make a parallel, following Table 1, we would say that an IC1 Iconographical Atom corresponds to the notion of datum, or the recognised physical container which is the subject of an assignment of status. The IC9 Representation would instead correspond to the determination of the representation on the basis of the cognitive type and the semantic marks associated with it, which partially correspond with the iconographical description outlined by Van Staten.

In order to annotate how the interpretation of a visual item works, we introduced the class IC12 Visual Recognition, which defines the act of recognition and interpretation of the subject matter of a representation.

The class describes the process of recognition of a representation using a fairly simple schema:

| persona | in | contextz |

| persona | assesses | Objectx |

| persona | assigns | valuey |

The above schema, as discussed in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, is the base of the interpretative act, and the only variables are the context, the classified object (Iconographical Atom) and the value assigned (Representation or Attribute). The class IC12 Visual Recognition respects and reproduces this schema, making it possible to describe, for example, the representative value assigned to an image by different art historians, thus enabling the system to keep track of the persons assessing a specific object. Moreover, the use of such a construct would help us record the set of features in a representation considered more salient by a viewer than others within a historical period. In the context of VIR, we call those features Attributes. The clustering of the Attributes together with the Representation they belong to is essential for the analysis of the association between semantic marks and the cognitive type they represent, in order to show their development and changes over time.

Sometimes a Representation with a clearly denoted identity can develop a different one within the same context. This process is called connotation. Visual semiotics discern denotation and connotation as two different layers of meaning, where denotation expresses what is being depicted and connotation expresses the values and ideas of what is represented [39]. The connotative layer has been the subject of many studies, with very diverse interpretations about its nature. Barthes, for example, thought that there is no encoding/decoding function within the denotative layer because our object recognition originates from some form of “anthropological knowledge” [47]. While appealing, this description seems to be tip-toeing around the subject, explaining a significant feature of the perception process using a fuzzy concept. We prefer the definition given by Hjelmslev [48] of a “semiotics whose expression plane is a semiotic,” so a function that relates the content of a signification to the expression of a further content. For these reasons, in this ontology we model the connotation as a relationship between the already established Representation and a conceptual object, and not as a new relationship between a Representation and an Iconographical Atom. The persistence of the connotation is transitory, because connotations are founded only on code convention and time-wise are less stable than denotation, because their duration is influenced by the stability of the convention itself.

4.4. Application Examples

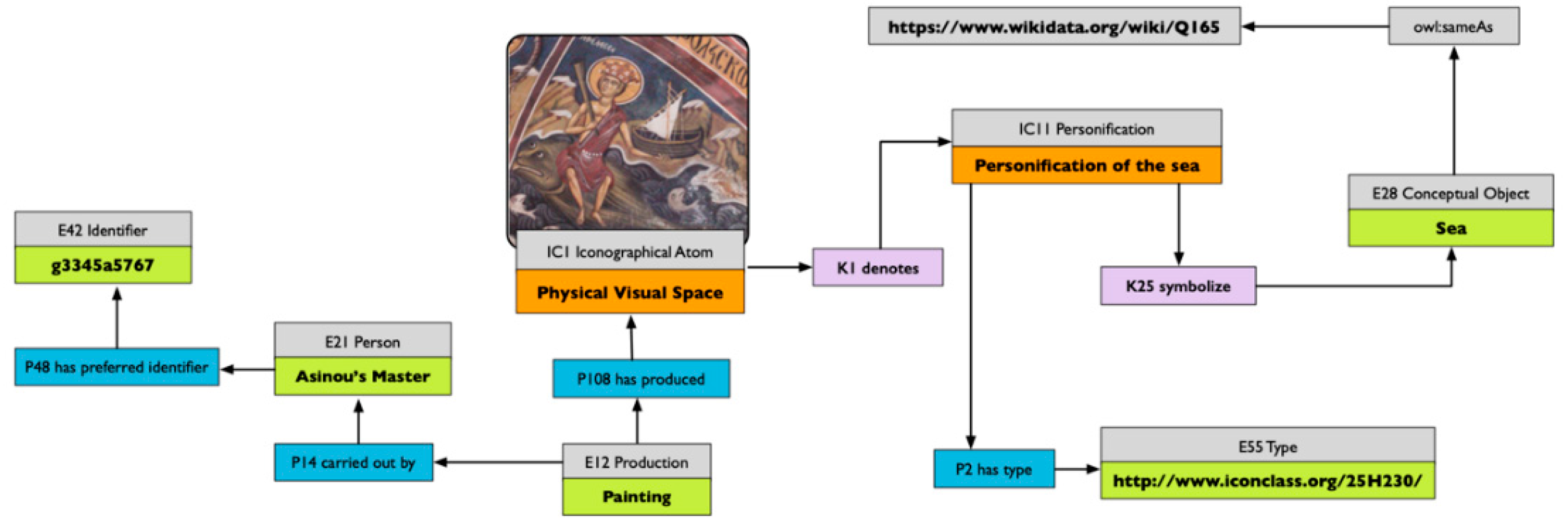

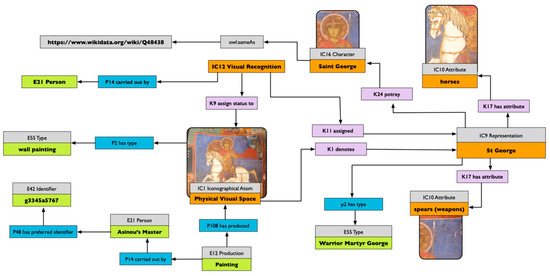

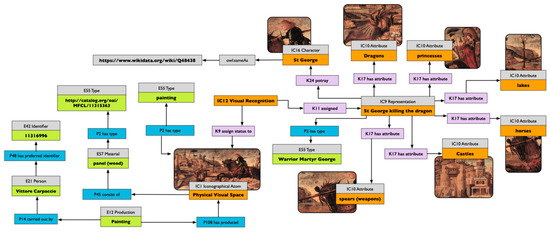

After having outlined the basic structure of VIR in Section 4.2, this section emphasises the capabilities of the ontology using examples from two datasets, one describing the wall painting in the narthex of the church of Asinou and the second one describing the collection of the Photographic Archive of the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies. For each of the examples, we present an ontological mapping of the information using CIDOC-CRM and VIR. While initially done in RDF (Resource Description Framework), the maps have been transformed, for readability purpose, into graphical representations.

The purpose of these graphs is to provide to the reader with an example of the applications of the developed ontology, as well as to display how the information present in just a small portion of a wall painting, if correctly described, can help create an information-rich environment that opens the doors to new ways to document a heritage object in relation to its functional and visual context. For easy reading, we specify that the letters K and IC represent, respectively, the properties and the classes of the VIR ontology colour-coded in the graph in purple and orange, while the letters P and E, colour-coded in blue and green, represent the properties and classes belonging to the CIDOC-CRM ontology.

4.4.1. On Representation and Attribute

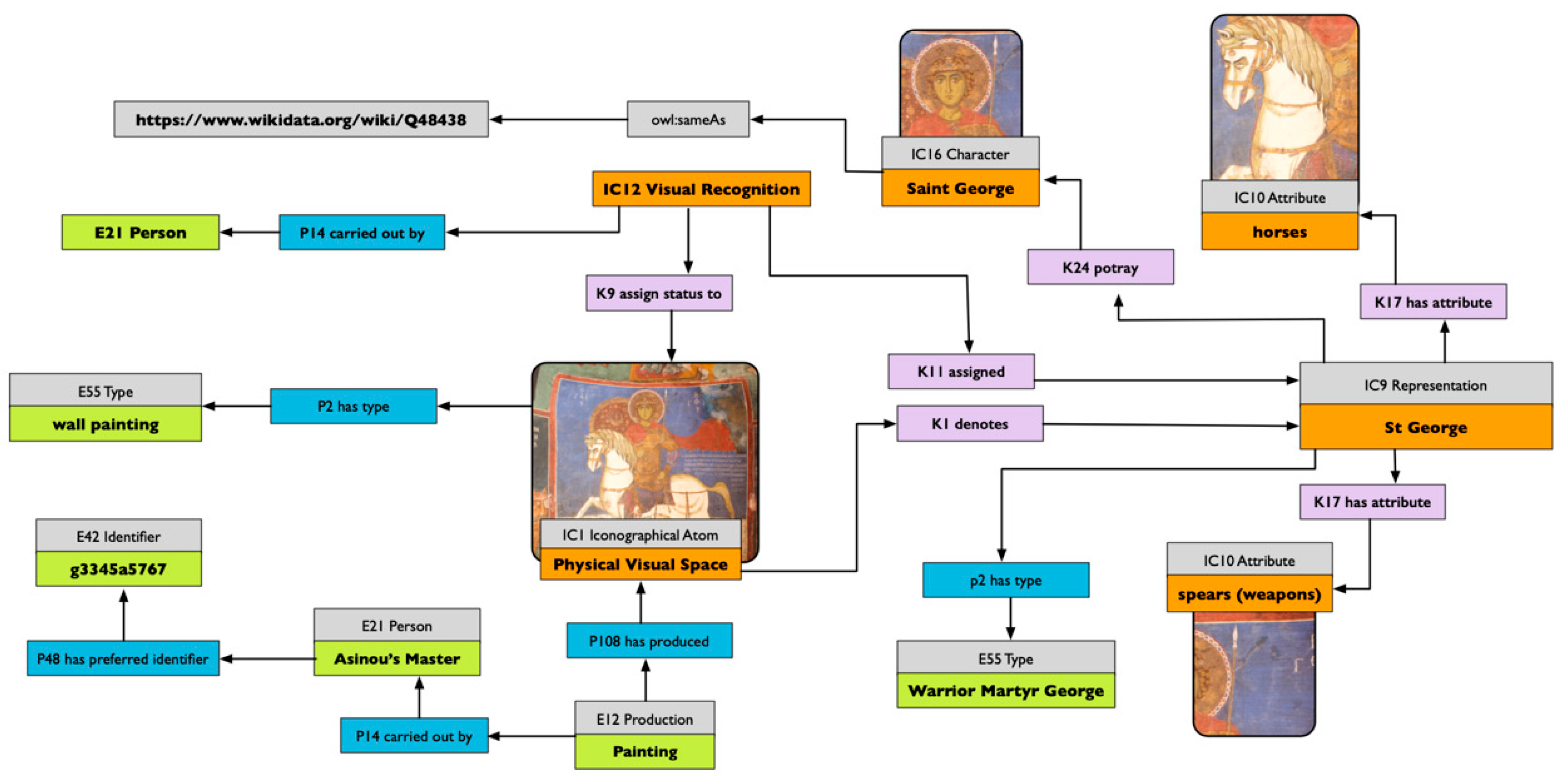

The graph in Figure 3 outlines the map of the information about the panel of Saint George in the church of Asinou. The map presents the description of the Visual Recognition of the representation of Saint George, which assigns the status of a representation to the iconographical atom in the south lunette of the narthex of the Asinou church. The representation is identified here as “Saint George.” However, the recognition of a specific subject is dependent on the knowledge the interpreter has of the context of production. A felicitous recognition is conditioned by a grasp of the context of the artwork, because, while many would recognise Saint George as the main subject of this wall painting, many others, not familiar with Christian iconography, would only recognise a man riding a horse. An expert in Byzantine iconography could instead quickly identify him as Diasorites, a more specific iconographical type. It is important to underline that such diversity in classification in respect to the same representation is, indeed, possible. The modelling in Figure 3 does represent only one of these possible recognitions (the one originally described in the record), but the same assertion, which assigns a representation value to an iconographical atom, is repeatable. We could have, therefore, an instance of IC1 Iconographical Atom acting as a hub of diverse visual interpretations carried out by different art historians who do not share the same knowledge on the subject, or who decide to diverge on the type of attribution (e.g., generic vs. specific). The (possible) selection of a chosen interpretation is not an ontological problem but an institutional one, and should be carried out on the basis of the provenance of the selected assertions.

Figure 3.

Map of the information about the Saint George wall painting in Asinou, Cyprus. Ontology used: VIR and CRM.

An IC12 Visual Recognition results in the constituency of an instance of the class representation that is further described as portraying the character of Saint George. This relationship is achieved using the property “K24 portray.” Using the representation as a vehicle to record propositions about the visual object, we define its iconographical type, using the property “P2 has type” from CIDOC-CRM. In the example in Figure 3, we used our own internal vocabulary, but it could easily be linked with external ones. More interesting is the possibility of defining the attributes of the representation, which in Figure 3 are the horse and the spear.

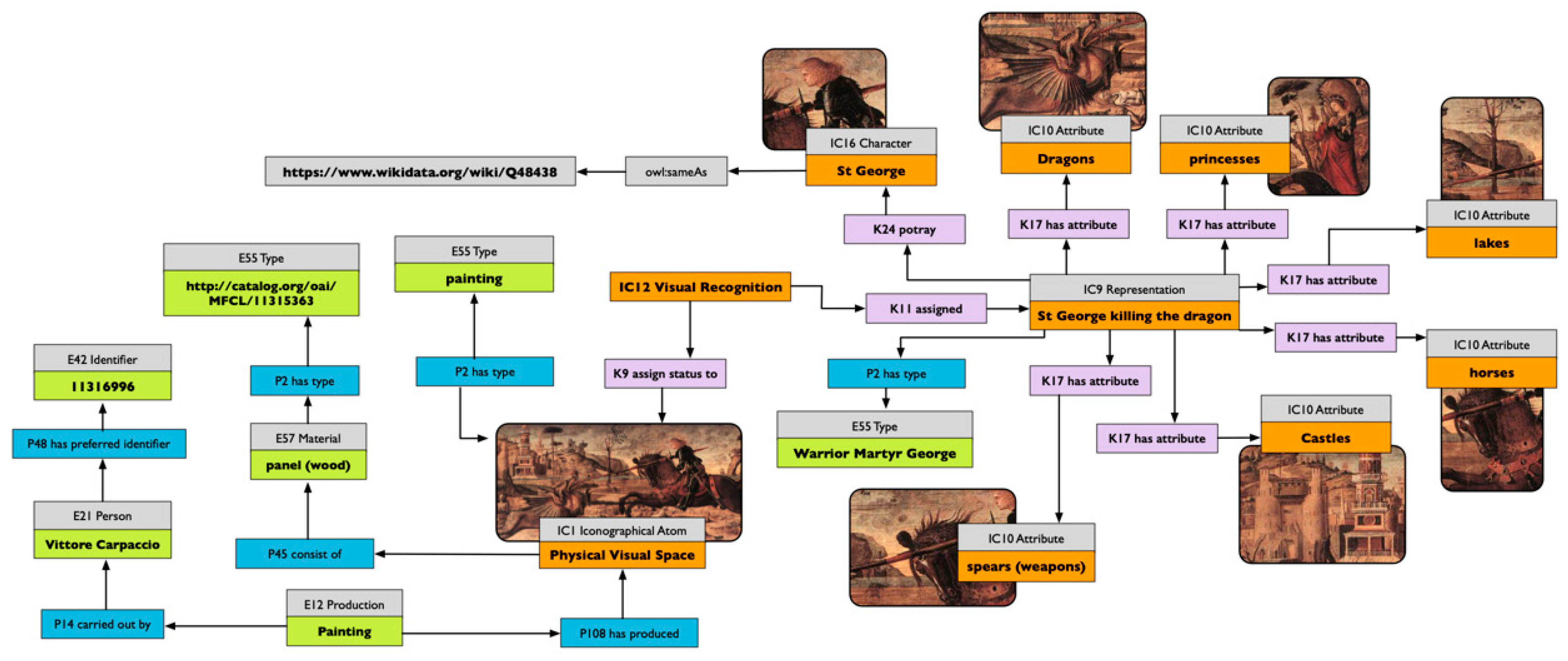

Figure 4 presents the map of the description of “Saint George killing the dragon” by Vittore Carpaccio from the Photographic Archive of the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies. It is easy to see that in this representation, the figure of Saint George is richer in attributes (Castle, Princess, Lake and Dragon) in respect to Figure 3. The two representations of Saint George in Figure 3 and Figure 4 do carry their own diverse identities, but can be easily correlated using their shared set of elements. The correlation can be based, for example, on the depicted character. In this instance, they both describe the character called Saint George, and even if the nomenclature in the two records is not the same (in Figure 4 we have St George, while in Figure 3 we have Saint George), they both use external resources (in this case Wikidata) to define the identity of the portrayed character. Another important feature that can be used for correlating the records is the class Attribute. The two attributes used for the description of the panel of Saint George in Asinou are also used for the description of Saint George by Vittore Carpaccio. While the latter uses a larger set of elements, the spear and the horse are shared by both representations, and, if adequately modelled, we would be able to link the representations on the basis of the visual elements used to characterise the saint.

Figure 4.

Map of information about the iconography of Saint George killing a dragon on the basis of the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies record. Ontology used: VIR and CRM.

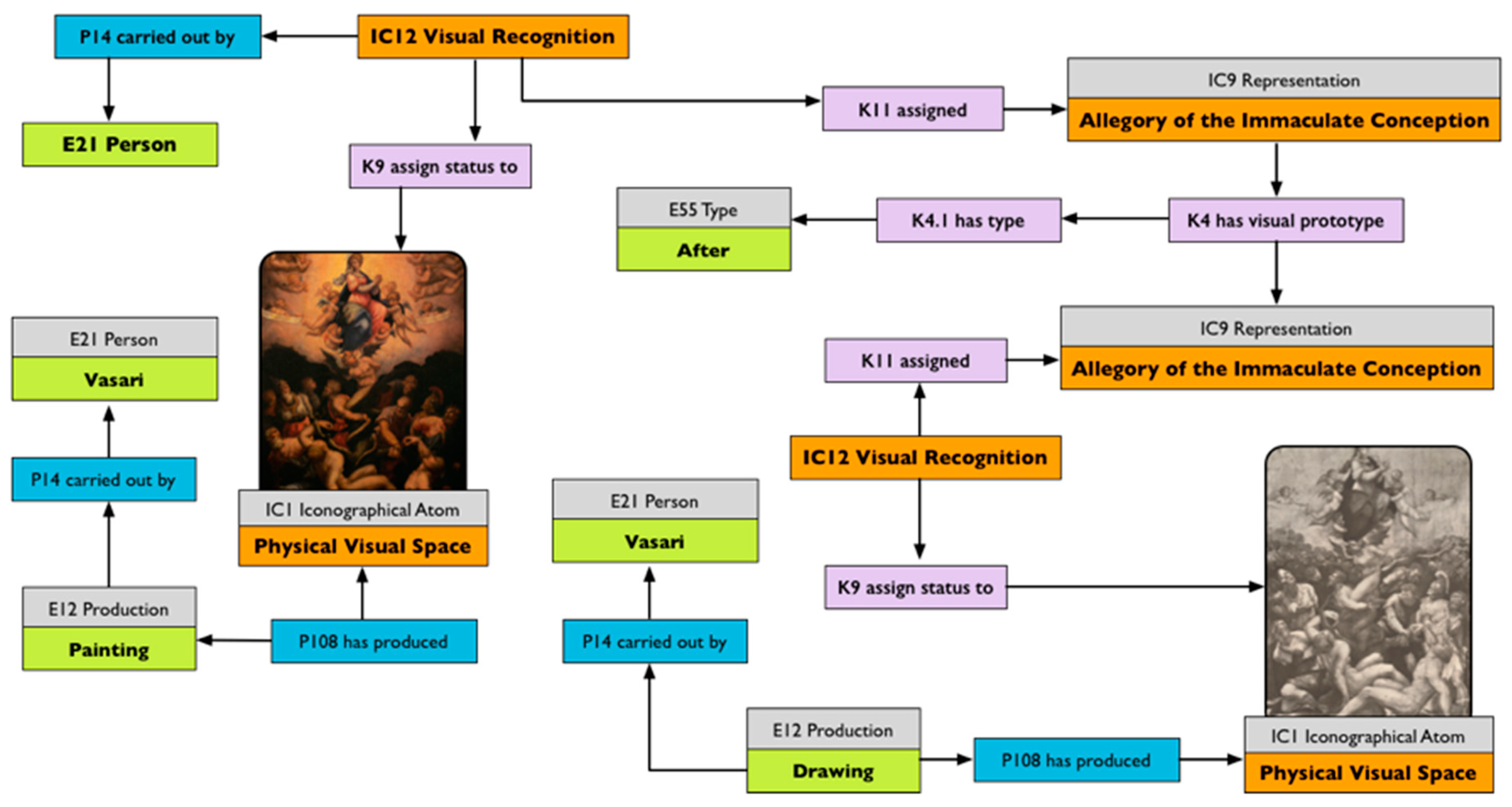

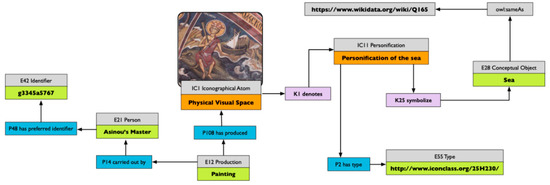

4.4.2. On Personification and Prototype

A specific type of Representation that is necessary to mention and describe here is Personification, identified in VIR by the identifier IC11. The class comprises anthropomorphic figures, which symbolise and represent abstract ideas. Widely used within the arts, Personification appears in both Byzantine and Western traditions and is considered a typical communicative device to represent intangible concepts such as Fortune, Fate, Prudence and other allegories. Another typical use of Personification that still survives today is that of national symbols: anthropomorphic figures that embody a nation and its values (e.g., Marianne for France).

Figure 5 presents a map of information on the personification of the sea present in the narthex of the church of Asinou, Cyprus. The relationships described in Figure 5 are quite similar to the ones used for the description of a Representation, but, in this case, the symbolic link with a conceptual object is made explicit. As for the representation of Saint George, the characteristics of a personification can also be shared by similar representations, so it is crucial to link the semantic information with external reference resources. In Figure 5, for example, both the symbolic object and the personification are linked, with Wikidata and Iconclass, respectively.

Figure 5.

Personification of the sea. Asinou, Cyprus.

The grounding of such information using a formal ontology enables diverse possible combinations of queries, searching, for example, for a specific mix of attributes and symbolic content expressed by a personification.

Few words need to be spent on another important relationship encoded in the ontology, that of prototype. Representation, sometimes at least, has to be seen as the result of a long process that involves preparatory study and sketches of what, in the end, will be the final version of an artwork.

This process is described using several types of attributes (e.g., study for, preparatory, version, prototype, studio), which we do not define as different single properties (which would create a semantic closed system), but we group together into a single relationship. We created the class K4 visual prototype together with the property K4.1 prototypical model as a n-ary construct for documenting the type of prototype used for the creation of an image. A preparatory sketch, for example, would be described as a prototypical version of the final artwork. The description schema is, fairly simply:

| representationa | hasPrototype | prototypex |

| prototypex | hasType | “preliminary version” |

| representationb | isPrototypeof | prototypex |

The n-ary construct allows us to relate the two representations, which are connected together using a class which we can further specialise, including the type of relationship that exists between the two representations. In our example we used the type “preliminary version,” but diverse types can be used. The same relationships that connect a preparatory study and the final artwork could be easily used for relating a copy to the original. The copy is, in fact, nothing else than a new object which uses another one as an example. The type of resemblance between the two is just a perceptual judgment, which does not change the process of reusing another object as a prototype for a new one. Using this type of relationship, we can easily visualise the process of creation of an artwork through the use of the diverse prototypes/versions that follow one another until the final object come into being.

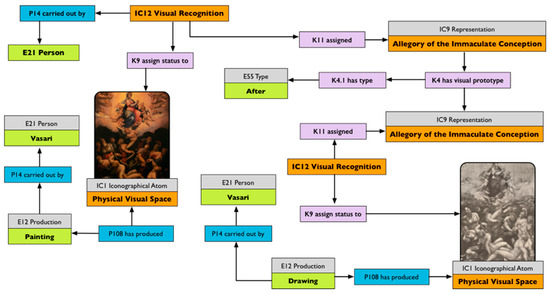

The map in Figure 6 of the relationship between the Allegory of the Immaculate Conception by Vasari, as held in the church of Santi Apostoli in Florence, and the preparatory study made by the artist, helps us visualise the structure of this relationship. The two Representations are linked together by a type of visual prototype, in this case, a “Studio for.”

Figure 6.

Prototypical relation between an initial study and the final outcome of Vasari’s Allegory of the Immaculate Conception.

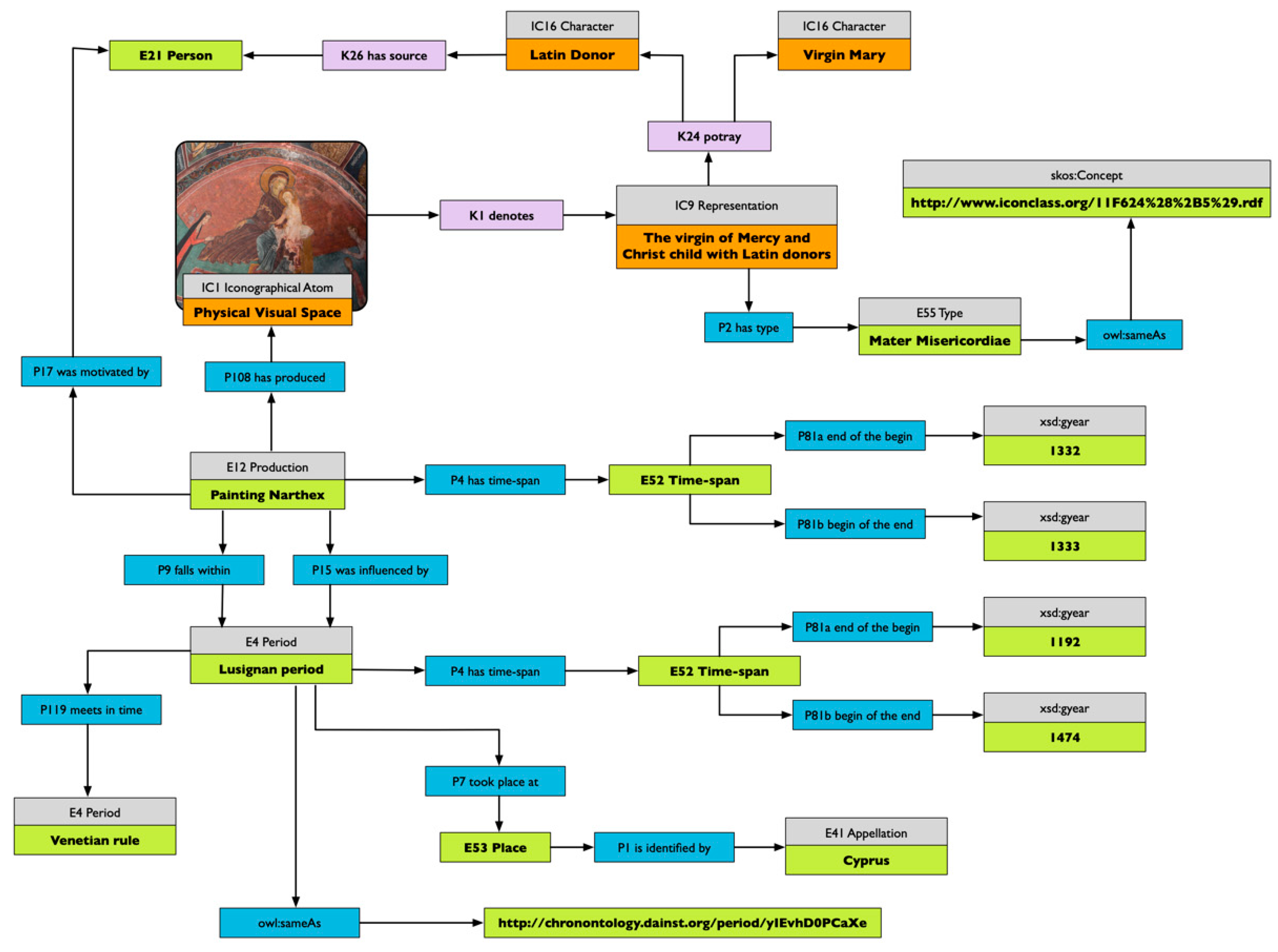

4.5. On Historical Grounding

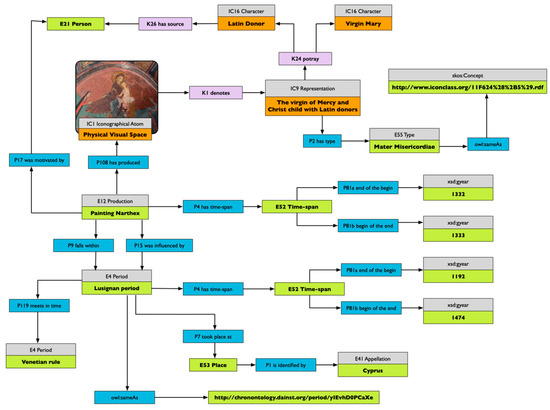

The descriptions of the ontology and the examples have been, until now, dedicated only to the description of the visual, overlooking another essential component in art, the historical aspect. In order to accurately describe a representation as a product of its time and space, and bind it to specific traditions or visual culture, it is essential to ground the visual information into a bigger historical framework. This approach enables users to focus not only on aesthetic attributes, but also on the development of symbolic forms or characters within a period. The church of Asinou proves to be again an excellent example to explain the importance of such practice. The top part of the south conch in the narthex of the church hosts the panel “Virgin of Mercy and Latin Donor,” an iconographical type original from the West. This iconography, called Madonna della Misericordia, originated in Italy in the early 13th century and was promptly disseminated in the Mediterranean area by the crusaders [49].

In this case, it is crucial to ground the iconographical information within its history, defining the influence on the production of the painting of both the donor and the Frankish occupation of the island. Figure 7 documents the integration of the aesthetic information within the historical framework of production. The creation of the painting is linked in time with the Lusignan occupation of the island, from 1192 till 1474. The period is, moreover, linked with two other spatio-temporal gazetteers, perio.do2 and chronontology3, which help in retrieval and also in the browsing and visualisation of further documented periods.

Figure 7.

Map of the historical information about the panel “Virgin of Mercy and Latin Donor” in the south conch of the Narthex of the Asinou church, Cyprus.

Using this modelling, we can easily cluster and browse information about representations created in a specific period or location, and, thanks to the class and property defined by VIR, we can explore the use of specific symbols or iconographical types within historical periods.

The link between visual representations and historical information within a formal structure that can be queried is the first step towards achieving a true digital iconological framework able to correlate visual culture and symbolism used.

5. Application

We briefly touched the surface of the possible applications of the ontology. It is important to understand that such a flexible structure can be of use in diverse fields and scenarios, ranging from the constructions of intelligible labels to the definition of a schema for recording user annotation over visual objects. The latter is undoubtedly the most common use, especially thanks to the technological advancements that have emerged in recent years. The rise of IIIF (International Image Interoperability Framework) as a standard for viewing and sharing image collections has ignited the development of viewers’ applications rich in annotation capabilities (Mirador4 is probably the most famous example). The possibility of classifying a user-defined spatial area as a representation, as well as correlating it with the iconographical attributes appearing within the image (throughout other annotations), is the first and a necessary step towards creating an iconographical corpus. The use of the ontology together with this type of software would greatly help in the creation of a dataset of attributes, subjects, characters and symbols, allowing researchers to automatically cluster this type of information and perform further research on the interconnections between these elements.

While annotators built on top of IIIF viewers or other 2D/3D technology are undoubtedly the most common example of use, the ontology could also be used in correlation with machine learning (ML) algorithms. This type of algorithm excels in assigning labels to pictures, but falls behind when structuring the information they produce. It is conceivable that ML algorithms could be used to define a series of attributes for each representation, using the ontology to record them in a database.

While the ontology can be used as a schema for any information system, it does provide the best possible outcome as a way to structure information in an RDF store where, thanks to the SPARQL query language, we would be able to integrate linked data coming from other sources. A straightforward example would be to use Iconclass, probably the primary classification system in the domain of iconography, to obtain normalised terminological entry for the description of attributes and types. We could then easily use SPARQL to directly query an Iconclass graph to find the necessary nomenclature for the definition of the chosen attributes, or the type of iconographical representation we are dealing with, relying on the structure of the ontology for their integration.

6. Limitations

The ontology proposed here is not exempt from limitations. The contextualisation of CT in the initial analysis was supported by the use of situation and situation type. The introduction of situation and situation type is indeed possible in RDF, but it would require the constant use of reification, which would drown the usefulness of the ontology in order to pursue an unnecessary purity. Another solution would be the creation of the class Situation, which would involve a set of physical entities in a definite configuration. A Representation would then conform/not conform to the Situation where the Visual Recognition takes place. The possibility of using Situations for differentiating between the meanings of the visual would greatly help in those performance types where the use of the visual element is strongly symbolic. Similar achievements could be done with a connotation. However, the data demonstrate that, for now, the desire is small for such a complex structure, and a bigger effort from the community is required before a real contextual model could take place. Moreover, the necessity of grounding a visual recognition within a situation would considerably raise the complexity of both the recording and the querying of the data, without really great advantages from a practical perspective.

The richness in representations of the same subject with very different attributes has been discussed in Section 4.2. While, when using the ontology, it is possible to assign identity to the various components of a representation and link the diverse types of depictions with the same subject or character together, it is not a fully resolved issue. If the attribute and the characters are not properly annotated, the machine can do very little to resolve a human error or bias. The co-referencing problem should be dealt with relying on human judgment, semantic automation (e.g., SILK) or using the similarity constraints outlined in Section 3.3: Topological, Feature, Alignment or Value information. While the feature can be easily defined using the ontology, the topology, alignment and value necessitate the help of diverse algorithms, such as the one used in machine learning, which can calculate the colour value present in two representation as well as their geometrical similarity, and then propose to the user the integration of the information.

7. Conclusions

The article presents an overview of a functional theory of perception, defining the nuclear terms used in the classification of visual objects, and re-proposing some of the identified structures and process within a new ontology, called VIR, which extends CIDOC-CRM for describing the diverse type of representations of and relationships between visual features. Specifically, the ontology provides the possibility of defining relationships between prototypical objects used within a visual composition, iconographical objects, attributes of the representations, layering of diverse representations, compositionality, subject matter, personification, illustrations of a scene and others. Examples are provided for the core elements of the ontology, in order to explain both its use and rationale.

The approach proposed, allows description of diversity in interpretation, as well as the rationale used for the classification of visual items and their interconnection with other objects that share the same symbolic meaning or refer to the same personification/phenomenon.

Supplementary Materials

The VIR ontology, together with further documentation on its use, is available online https://w3id.org/vir.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation and formal analysis: N.C.; administration, supervision conceptualization and validation: L.d.L.

Funding

Part of this research was funded under the European Project Marie Curie ITN-DCH (Initial Training Network for Digital Cultural Heritage), which has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no 608013.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- D’Andrea, A.; Ferrandino, G. Shared Iconographical Representations with Ontological Models. In Proceedings of the Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology, Berlin, Germany, 2–6 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gangemi, A.; Mika, P. Understanding the Semantic Web through Descriptions and Situations. In Proceedings of the on the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems, Sicily, Italy, 3–7 November 2003; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 689–706. [Google Scholar]

- Tzouveli, P.K.; Simou, N.; Stamou, G.B.; Kollias, S.D. Semantic Classification of Byzantine Icons. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2009, 24, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, L.; Busayarat, C.; Domenico, F.D.; Lombardo, J.; Stefani, C.; Pierrot-Deseilligny, M.; Wang, F. When script engravings reveal a semantic link between the conceptual and the spatial dimensions of a monument: The case of the tomb of Emperor Qianlong. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHeritage), Marseille, France, 28 October–1 November 2013; Volume 1, pp. 505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Gonano, C.M. Un Esperienza di Rappresentazione di dati di Cataloghi Digitali in Linked Open Data: Il Caso Della Fondazione Zeri. Ph.D. Thesis, Università di Bologna, Bologna, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Daquino, M.; Mambelli, F.; Peroni, S.; Tomasi, F.; Vitali, F. Enhancing semantic expressivity in the cultural heritage domain: Exposing the Zeri Photo Archive as Linked Open Data. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2017, 10, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mambelli, F. Una risorsa online per la storia dell’arte: il database della Fondazione Federico Zeri. Quad. DigiLab 2014, 3, 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Reist, I.; Farneth, D.; Stein, R.S.; Weda, R. An introduction to PHAROS: aggregating free access to 31 million digitized images and counting. In Proceedings of the CIDOC 2015, New Delhi, India, 5–10 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Daquino, M.; Tomasi, F. Historical Context Ontology (HiCO)—A Conceptual Model for Describing Context Information of Cultural Heritage Objects. In Metadata and Semantics Research; Garoufallou, E., Hartley, R.J., Gaitanou, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 424–436. ISBN 978-3-642-35232-4. [Google Scholar]

- Peroni, S.; Shotton, D.; Vitali, F. Scholarly publishing and linked data: describing roles, statuses, temporal and contextual extents. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Semantic System, Graz, Austria, 5–7 September 2012; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Peroni, S.; Shotton, D.M. FaBiO and CiTO—Ontologies for describing bibliographic resources and citations. J. Web Semant. Sci. Serv. Agents World Wide Web 2012, 17, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L. The Philosophy of Information; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, D.M. Information, Mechanism and Meaning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969; ISBN 978-0-262-63032-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind; Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972; ISBN 978-0-226-03905-3. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. Kant and the platypus: Essays on language and cognition; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rosch, E.; Lloyd, B.B. Cognition and Categorization; Lawrence Elbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1978; ISBN 978-0-8357-3404-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008; ISBN 0-226-47101-2. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanovic, I. Situation Semantics. In Identity, Language, and Mind: An Introduction to the Philosophy of John Perry; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, K. Situation theory and situation semantics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; ISBN 978-0-444-51622-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zucchi, S. Events and Situations. Annu. Rev. Linguist. 2015, 1, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R. Type theory and semantics in flux. Handb. Philos. Sci. 2012, 14, 271–323. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. Mereotopology: A theory of parts and boundaries. Data Knowl. Eng. 1996, 20, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Varzi, A. Bona Fide and Fiat Boundaries. Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 2000, 60, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varzi, A.C. Reasoning about space: The hole story. Log. Log. Philos. 2003, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freksa, C. Temporal reasoning based on semi-intervals. Artif. Intell. 1992, 54, 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, R.L.; Son, J.Y. Similarity. In The Oxford Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, T.J. Fuzzy Logic with Engineering Applications; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-119-23585-9. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. Lector in fabula: la cooperazione interpretativa nei testi narrativi; Bompiani: Milano, Italy, 1979; ISBN 88-452-1221-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, M.; Bryson, N. Semiotics and Art History. Art Bull. 1991, 73, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, S. Introduzione. In Iconologia; Maffei, S., Procaccioli, P., Eds.; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 2012; ISBN 978-88-06-21151-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cartari, V. Le immagini degli dei degli antichi; Francesco Marcolini: Venezia, Italy, 1556. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, N. Mythologiae sive explicationis fabularum; ad signum Fontis: Venezia, Italy, 1596. [Google Scholar]

- Ripa, C. Iconologia overo Descrittione di diverse imagini cavate dall’antichità e di propria inventione; Appresso Lepido Facij: Roma, Italy, 1603. [Google Scholar]

- Van Straten, R. An Introduction to Iconography; Symbols, Allusions and Meaning in the Visual Arts; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 1-136-61402-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W.J.T. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, E. Studies in Iconology. Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, B.; Ringham, F. Dictionary of Semiotics; Cassell: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-304-70636-1. [Google Scholar]

- Polidoro, P. Che cos’è la semiotica visiva; Carocci editore: Roma, Italy, 2008; ISBN 978-88-430-4579-2. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, T. Semiotics and Iconography. In The Handbook of Visual Analysis; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2001; pp. 92–118. ISBN 978-0-7619-6477-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Outline of a Theory of Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977; ISBN 1-107-26811-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier, P. Mundane Objects: Materiality and Non-Verbal Communication; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 10, ISBN 1-61132-056-9. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, A.W.; Nicolaïdès, A. Asinou Across Time; Studies in the Architecture and Murals of the Panagia Phorbiotissa, Cyprus; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-88402-349-4. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianou, A.; Stylianou, J. The Painted Churches of Cyprus; Treasures of Byzantine Art; A. G. Levantis Foundation: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Busine, L.; Sellink, M. The glory of Saint George: man, dragon, and death; Mercatorfonds: Brussels, Belgium; New Haven, CT, USA, 2015; ISBN 94-6230-076-3. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, C. The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK; Burlington, VT, USA, 2003; ISBN 1-84014-694-X. [Google Scholar]

- Garry, J.; El-Shamy, H. Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-7656-2953-1. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R. Rhétorique de l’image. Communications 1964, 4, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmslev, L. Prolegomena to a Theory of Language; The University of Wisconsinc Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1963; ISBN 560789956. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, M. La Madonna della Misericordia individuale. Acta Ad Archaeol. Artium Hist. Pertin. 2017, 21, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The ontology is freely available, together with its documentation, from https://w3id.org/vir/ (Supplementary Materials). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).