Planning for the Enhancement of the Modern Built Heritage in Thessaly Region: The Case of the “Konakia” Monuments

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodological and Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Methodology of the Research

2.2. Theoretical Approaches and Tools for the Management and Protection of Cultural Heritage

3. The Case of the “Konakia” Monuments in the Thessaly Region

3.1. General and Historical Information on the Study Area and the “Konakia”

3.2. Key Spatial Characteristics of the “Konakia” Monuments

3.3. Evaluation and Discussion

3.4. Towards a Six (6)-Step Methodology for the Wise Management and Protection of the “Konakia” Monuments

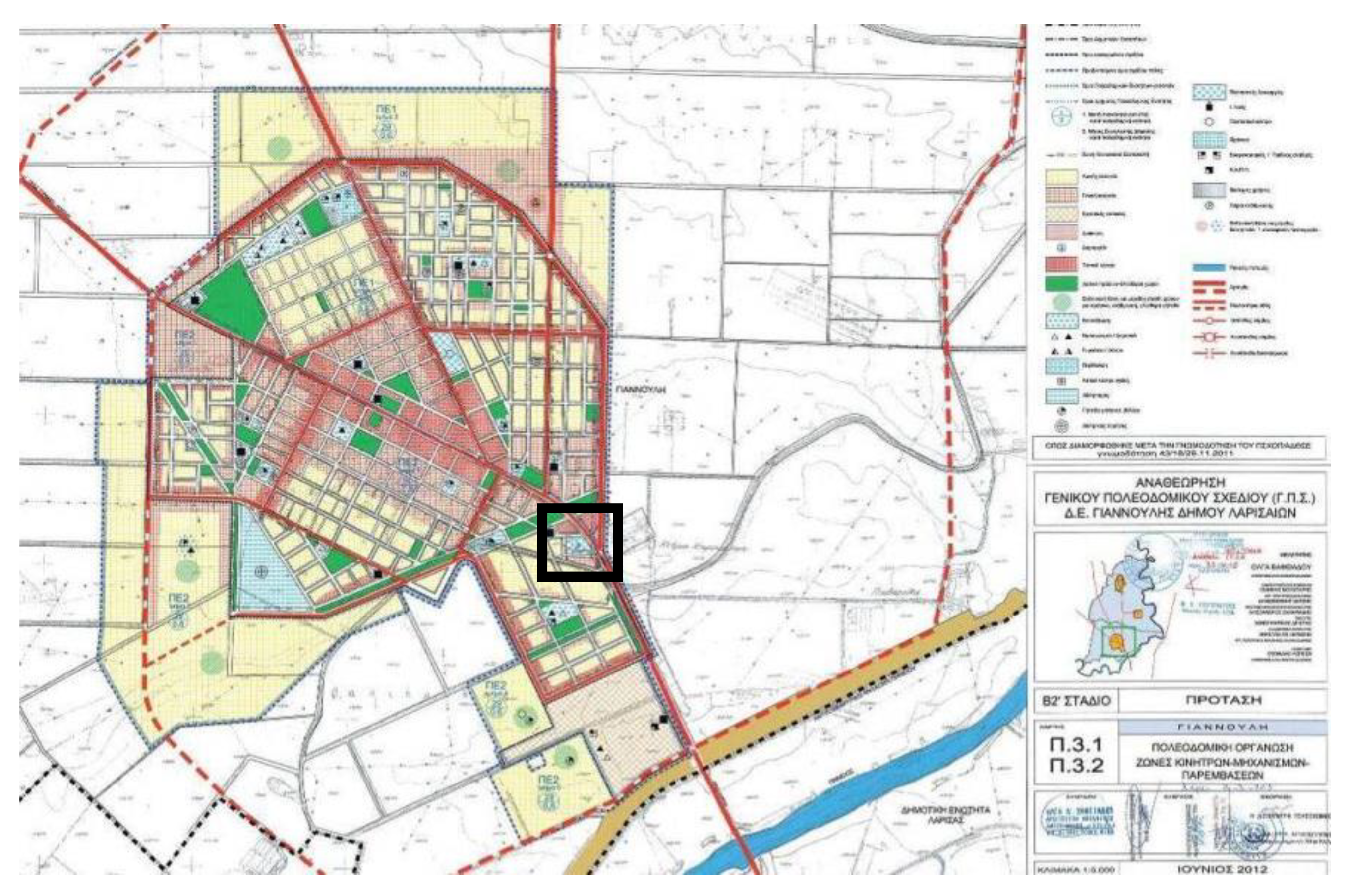

4. The Case of the Harokopos Tower “Konakia”

4.1. Key Information and Features

4.2. Management and Planning Proposals: Implementing the Six (6)-Step Methodology

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kunzmann, K.R. Culture, creativity and spatial planning. Town Plan. Rev. 2004, 75, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geppert, A. Planning systems facing heritage issues in Europe: From protection to management, in the plural interpretations of the values of the past. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2004, 21, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gospodini, A.; Beriatos, E.; Raskou, E. Architectural heritage conservation: Progress in politics in Europe and new challenges for Greece. Aeichoros 2007, 6, 146–173. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Poulios, I. Discussing strategy in heritage conservation: Living heritage approach as an example of strategic innovation. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, I. Tangible Cultural Heritage Conservation, Local Community and Sustainable Development. In Heritage Conservation, Local Community and Sustainable Development; Poulios, I., Alivisatou, M., Arabatzis, G., Giannakidis, A., Karachalis, N., Mascha, E., Mouliou, M., Papadaki, M., Prosilis, C., Touloupa, S., Eds.; Association of Greek Academic Libraries: Athens, Greece, 2015; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11419/2395 (accessed on 1 September 2018). (In Greek)

- UNESCO. New Life for Historic Cities: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach Explained. 2013. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000220957 (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. (Eds.) Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, K. The Historic Urban Landscape paradigm and cities as cultural landscapes. Challenging orthodoxy in urban conservation. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski, J.; Vass-Bowen, N. Buffering external threats to heritage conservation areas: A planners perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1997, 37, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, M. Planning practices for the protection of cultural heritage in Greece: Lessons learnt from the Greek UNESCO sites. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2015, 22, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, S. The value and valuation of maritime cultural heritage. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2011, 18, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maarleveled, T.J. The maritime paradox: Does international heritage exist? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsby, D. Cultural Capital. J. Cult. Econ. 2001, 23, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navrud, S.; Ready, R. Valuing Cultural Heritage: Applying Environmental Valuation Techniques to Historic Buildings, Monuments, and Artifacts; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Champ, P.; Boyle, K.J.; Brown, T.C. (Eds.) A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation; Kluwer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, M. Underwater cultural heritage facing spatial planning: Legislative and technical issues. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 165, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patronis, V. Greek Economical History; Association of Greek Academic Libraries: Athens, Greece, 2015; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11419/1700 (accessed on 1 September 2018). (In Greek)

- Aroni-Tsichli, K. Agricultural Issue: Thessaly—New Lands 1909–1922. In History of the New Greek Nation: 1770–2000; Panagiotopoulos, B., Ed.; Hellenica Grammata: Athens, Greece, 2003; Volume 6, pp. 267–282. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Yelling, J.A. Common Field and Enclosure in England 1450–1850; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G.; Clark, A. Common rights to land in England, 1475–1839. J. Econ. Hist. 2001, 61, 1009–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi-Doria, M. The land tenure system and class in southern Italy. Am. Hist. Rev. 1958, 64, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Took, L. Land Tenure and Rural Social Change: The Italian Case (Landbesitzverhältnisse und sozialer Wandel auf dem Lande: Das Beispiel Italien). Erdkunde 1983, 37, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedertscheider, M.; Erb, K. Land system change in Italy from 1884 to 2007: Analysing the North–South divergence on the basis of an integrated indicator framework. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgitsogianni, E. Panagis A. Harokopos (1835–1911): His Life and Work; Nea Synora: Athens, Greece, 2000. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The Averof “konakia” is not yet designated part of the modern built heritage of Thessaly, as it was built much later than the others (in the mid-20th century). Today, it is the property of the Municipality of Larissa, which is interested in launching a reconstruction and regeneration project. |

| Planning Zones under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Culture | |

| 1950 2002 | Landscapes of Outstanding Natural Beauty (in 2011 transferred to the Ministry for the Environment) Protection Zone A and Protection Zone B |

| Planning Zones under the jurisdiction of the Ministry for the Environment | |

| 1983 1997 | Zones for Building Activity Control (ZOE) (outdated zone) Special Protection Area (ΠΕΠ) (included in Local Spatial Plans / Urban Plans) |

| Names of the “Konakia” | Municipality | Location/Settlement | Population (2011) | Distance from Capital City |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harokopos G. | Larissa | within Giannouli city | 7847 | Larissa: 2.5 km |

| Harokopos P. | Farsala | within Polyneri settlement | 289 | Larissa: 59.0 km |

| Baltzis | Farsala | within Paleomylos settlement | 113 | Larissa: 65.0 km |

| Papageorgiou | Tempi | within Gyrtoni settlement | 74 | Larissa: 17.0 km |

| Hatzigakis | Kileler | within Sotirio settlement | 317 | Larissa: 31.0 km |

| Averof | Larissa | within Larissa city | 144,651 | Larissa: 0.0 km |

| Zournatzis | Trikala | Patoulia settlement | 511 | Trikala: 11.0 km |

| Ζappas | Trikala | within Meg. Kalyvia settlement | 1849 | Τrikala: 8.5 km |

| Zavitsianos | Pyli | within Pigi settlement | 1227 | Trikala: 9.0 km |

| Κoutsekis | Farkadona | within Ehalia city | 2357 | Trikala: 24.0 km |

| Μekios | Kalabaka | within Peristera settlement | 201 | Trikala: 19.0 km |

| Moufoubeis | Karditsa | Prodromos settlement | 811 | Karditsa: 5.5 km |

| Cohen | Palamas | Astritsa | 116 | Karditsa: 23.0 km |

| Zografos G. | Mouzaki | Lazarina | 437 | Karditsa: 26.0 km Trikala: 15.0 km |

| Zografos Ch. | Mouzaki | Agnandero | 1764 | Karditsa: 17.0 km Trikala: 12.0 km |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papandreou, A.; Papageorgiou, M. Planning for the Enhancement of the Modern Built Heritage in Thessaly Region: The Case of the “Konakia” Monuments. Heritage 2019, 2, 2039-2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030123

Papandreou A, Papageorgiou M. Planning for the Enhancement of the Modern Built Heritage in Thessaly Region: The Case of the “Konakia” Monuments. Heritage. 2019; 2(3):2039-2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030123

Chicago/Turabian StylePapandreou, Aikaterini, and Marilena Papageorgiou. 2019. "Planning for the Enhancement of the Modern Built Heritage in Thessaly Region: The Case of the “Konakia” Monuments" Heritage 2, no. 3: 2039-2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030123

APA StylePapandreou, A., & Papageorgiou, M. (2019). Planning for the Enhancement of the Modern Built Heritage in Thessaly Region: The Case of the “Konakia” Monuments. Heritage, 2(3), 2039-2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030123