Urban Heritage Conservation of China’s Historic Water Towns and the Role of Professor Ruan Yisan: Nanxun, Tongli, and Wuzhen

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Water Towns—A Story Still to be Written

“On a good day a riverboat could hope to cover fifteen to twenty-five kilometres. The imperial grain vessels seldom kept the same crew from start to end of a journey—there would be changes along the way [Grand Canal], and sometimes the grain might be stored in granaries en route if repairs or bad weather impeded progress. The lives of the river merchants and their captains were a constant procession of misty peaks and water towns, as elegantly conveyed by the Song painter Zhang Zeduan [2] in his famous scroll painting Along the River During the Qingming Festival”.

“Being an ancient township, Tong Li borders on Tongli Lake on the east, Nanxin Lake on the south, adjoins Pangshan Lake on the west, Jiuli Lake on the north and Wusong Jiang River on the northwest. The town proper is divided by the streams into seven islets interlaced with the surrounding water area, forming typical water county of the south”.[14]

2. Historic Water Towns to the South of the Yangtze River: Urban Form and Heritage

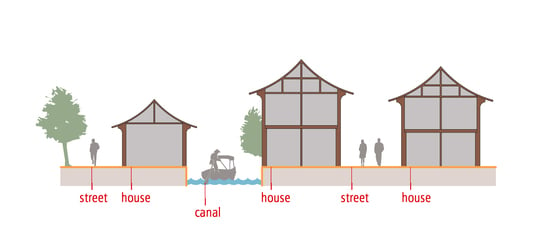

“Where there is only one river across the town, a belt-shaped town is formed. Where there are two or more rivers, a cross-shaped or tree-crotch-shaped town is formed (such as Wuzhen or Zhouzhuang, Figure in Section 5). Where there are four or even more rivers running through the town, grid-shaped towns are formed (such as Tongli, Figure 6).”.[4] (p. 25)

3. The Conservation of Historic Water Towns

3.1. Urban Conservation in China

3.2. Water Towns Conservation Planning and the Role of Ruan Yisan

“The comprehensive approach adopted by the project allows for thorough understanding and interpretation of the area’s natural and cultural heritage at both the local and regional levels. Operating with an overall conservation masterplan, a clear policy framework, and sound methodology, the project restores the authentic significance and function of the towns’ waterways and historic settlements, while accommodating modern needs and anticipated growth. Major investments by the government for public works and by residents for individual structures creates a commendable model of sustainable long-term public–private partnership. The ambitious scope of the project promises to have a major impact on shaping future developments in the towns as well as conservation practice throughout China.”.[4] (p. 15)

- -

- Raise local people’s awareness;

- -

- Focus on protection through development, putting forward the policy of “protecting ancient towns, constructing new zones, developing town’s economies, and opening up tourism” [4] (p. 175);

- -

- Proceed differently in response to different situations, which implies defining differentiated protection measures according to the different protection class that cultural heritage and sites belong to inside and outside the ancient towns;

- -

- Manage protection. Record and map existing towns in order to plan their protection, transformation, necessary reconstruction and reuse. “When planning, we should pay special attention to the inheritance and promotion of traditional culture such as traditional customs, products, handicrafts, snacks and dishes, literature and arts, etc.” [4] (p. 177)

- -

- Develop tourism accordingly. “The beautiful look with the special water town features, the plain and pure folkways and people, traditional dishes and snacks and the rich and colourful crafts the ancient towns possess are tourist sources people living long in cities crave for. On the one hand, we should enhance the ancient towns’ popularity via media’s propaganda; on the other hand, we established places in ancient towns and suitable places for serving tourists so that we could meet the tourists’ demands for ‘eating, living, walking, visiting, shopping and entertaining’”.

4. Historic Water Towns Conservation and Tourist Development

4.1. Nanxun, Tongli and Wuzhen—Three Cases Representing Different Implementations of Ruan Yisan’s Conservation Planning Approach

“Unlike some other ancient water towns, Nanxun is still inhabited. Furthermore, it is free to visit the town after 17:00 each day. Although tourist attractions and most shops will be closed after 17:00, tourists can still take a stroll through the town and observe the local people’s life. In some respects, the authentic town only emerges after 17:00 anyway.”.[49]

“Unlike some of the better known water towns, little of Wuzhen has been restored, yet many old buildings remain in a noteworthy state of preservation. Life in Wuzhen is much as it was in the past, with remarkably few buildings specifically serving tourists. Walking along any of the narrow lanes, one can easily glimpse the rhythms of daily life: people carting fresh water, cooking meals, tending to young children, and playing mah-jong. Local workshops continue to make wine and homespun cotton.”.[55] (p. 127)

4.2. Conservation and Tourism: a Difficult Marriage

5. In Conclusion: a Critical Assessment of Ruan Yisan’s Interventions as a Basis for Future Research

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ball, P. The Water Kingdom. A Secret History of China; The Bodley Head: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Yang Gu Su Fan Hua Tu [Xu Yang’s Flourishing City Gusu]; Commercial Press: Hong Kong, China, 1988.

- UNESCO World Heritage List. The Grand Canal. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1443 (accessed on 20 November 2017).

- Ruan, Y.S. Water Towns of the Yangtze River in China; a First Edition of This Book with 40 Pages Less Entitled Water Towns South of the Yangtze River, Was Published in 2004; Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B. Engineering Philosophy in the Grand Canal. In China and Italy: Routes of Culture, Valorisation and Management; Porfyriou, H., Yu, B., Eds.; CNR Ed: Rome, Italy, 2018; pp. 139–149. Available online: http://www.icvbc.cnr.it/Attivit%C3%A0/Editoria.html (accessed on 17 December 2018).

- Fei, X.T. (Ed.) Small Towns in China. Functions, Problems & Prospects; New World Press: Beijing, China, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Y. Jiangnan Shuixiang Guzhen Baohushijian [Practices for the Conservation of the Water Cities of Jiangnan]; National Research Centre of Historic City, Tongji University: Shanghai, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F. Small bridges, flowing streams and cottages. An introduction to Shaoxing, an area of rivers and lakes. In Chinese Vernacular Dwelling; Shan, D., Ed.; China Intercontinental Press: Beijing, China, 2004; pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. City in Space and Time: Development of the Urban Form and Space of Suzhou until 1911. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 1997. Available online: https://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/15758?show=full (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- Even the Big City of Suzhou, Famous for Its Classical Gardens and UNESCO World Heritage Site, Is Presented with This Branding in Wikipedia, Which Cites the New York Times and The Times. Wikipedia: Suzhou. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suzhou (accessed on 18 November 2017).

- Bellocq, M. Le patrimoine culturel comme ressource touristique: Le bourg ancien de Tongli, province du Jiangsu. L’Espace Géogr 2017, 46, 346–363, The English version of this article translated by Aruna Popuri, Cultural Heritage as Tourist Draw: The Ancient town of Tongli in the Jiangsu Province; pp. 1–18. Available online: https://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_EG_464_0346--cultural-heritage-as-touristdraw.htm (accessed on 17 December 2018).

- Official Presentation of Wuzhen Local Administrators during the Visit with Prof. Lu Bin of Peking University on 20 March 2015 in the Context of the European Project: PUMAH (2012–2016). Available online: https://www.ncl.ac.uk/guru/research/projects/planningurbanmanagementandheritagepumah.html (accessed on 18 November 2017).

- Suzhou Statistical Yearbook. 2016. Available online: http://www.sztjj.gov.cn/tjnj/2016/indexch.htm (accessed on 18 November 2017).

- The Township of Tong Li in Suzhou China. Available online: http://www.suzhou.gov.cn (accessed on 18 November 2017). (In English)

- Ruan, Y.S.; Li, Z.; Lin, L. Old Towns of Jiangnan: Conservation of Historical Architecture and Built Environment; Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Heath, T. Conservation and revitalization of historic streets in China: Pingjiang Street, Suzhou. J. Urban Des. 2017, 22, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S. The Ancient City of Suzhou: Town Planning in the Sung dynasty. Town Plan. Rev. 1983, 54, 194–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Real estate development and the transformation of urban space in China’s transitional economy, with special reference to Shanghai. In The New Chinese City: Globalisation and Market Reform; Logan, J.P., Ed.; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.M. Urban Development under Ambiguous Property Rights: A Case of China’s Transition Economy. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2002, 26, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.F. Forward to the past: Historical preservation in globalizing Shanghai. City Community 2008, 7, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.L.; Xu, J.; Yeh, A.G. Urban Development in Post-Reform China: State, Market, and Space; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Broudehoux, A.M. The Making and Selling of Post-Mao Beijing; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehand, J.W.R.; Gu, K. Urban conservation in China. Historical development, current practice and morphological approach. Town Plan. Rev. 2007, 78, 643–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresnais, J. La Protection du Patrimoine en République Populaire de Chine 1949–1999; Editions du C.T.H.S.: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S. (Ed.) Chengshi Guihua Fagui Duben [Readings in Urban Planning Laws and Regulations]; Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 1998; pp. 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y. The Study on Main Issues of Chinese and Italian Historic Centers’ Conservation Based on A Comparative Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Turin, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Conservation Policies and Planning of City Historic Sites. City Plan. Rev. 2004, 10, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. An Introduction to Integrated Conservation: A Way for the Projection of Cultural Heritage and Historic Environment; Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F. Traditional architectural forms in market oriented Chinese cities: Place for localities or symbol of culture? Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ged, F.; Marinos, A. (Eds.) Ville et Patrimoines en Chine; Catalogue Edité par l’Observatoire de L’architecture de la Chine Contemporaine D’après L’exposition Concue avec la Fondation Ruan Yisan à: Paris Oct 2009–Jan. 2010, Berlin Automne 2009, Londres Automne 2010; the Citation Is from the Preface to the Volume of Wang Jinghui (Consultant of MOHURD); Citè de L’architecture & du Patrimoine: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Heath, T. Heritage led Urban Regeneration in China; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.X.; Liu, X. (Eds.) Collection of International Symposium on Conservation of Historical Cities and Buildings; The University of Hunan Press: Changsha, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- College of Architecture & Urban Planning Tongji University (Ed.) Urban Heritage Conservation; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, B. L’engagement du professeur Ruan Yisan. Monde Chinois 2010, 22, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Marinos, A. Le partenariat franco-chinois en matière de protection du patrimoine. Monde Chinois 2010, 22, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X. Reconstructing Tradition: Heritage Authentication and Tourism-Related Commodification of the Ancient City of Pingyao. Sustainability 2018, 10, 670. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/3/670 (accessed on 20 December 2018). [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y. From a Living City to a World Heritage City—Authorized Heritage Conservation and Development Policies and Their Impact on the Local Community. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2012, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancient City of Pin Yao—Unesco WHC. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/812 (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- Ruan Yisan Foundation. Available online: https://www.revolvy.com/page/Ruan-Yisan-Heritage-Foundation (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- University of Notre Dame, Henry Hope Reed Award. Professor Ruan Yisan Has Been Awarded the Prize in 2014. Available online: https://architecture.nd.edu/news-events/events/henry-hope-reed-award/recipients/professor-ruan-yisan/ (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- Ruan, Y.S. Nanxun: Ancient Town in Jiangnan; Foreign Languages Press: Beijing, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Y.S. Shui Xiang Ming Zhen Nanxun; Tong Ji Da Xue Chu Ban She: Shanghai, China, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. Ancient Towns around Shanghai; Foreign Languages Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.C. (Ed.) Cities of Jiangnan in Late Imperial China; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Y.S. Nanxun; Zhejiang She Ying Chu Ban She: Hangzhou, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Taunay, B. Le Tourisme Intérieur Chinois; Presses Universitaires de Rennes: Rennes, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.; Wall, G.; Mitchell, C. Heritage retail centers, creative destruction and the water town of Luzhi, Kunshan, China. In Tourism in China. Destination, Cultures and Communities; Ryan, C., Gu, H., Eds.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 99–123. [Google Scholar]

- Sofield, T.H.B.; Li, F.M.S. Tourism development and cultural policies in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 362–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanxun Water Town Tours. Available online: https://www.shanghaihighlights.com/nanxun-tour/ (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- Yan, P. Tongli; Suzhou Daxue Chubanshe: Suzhou, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.B.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.J. Image of landscapes in ancient water towns. Case study on Zhouzhuang and Tongli of Jiangsu province. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2006, 16, 371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Bellocq, M. The Cultural Heritage Industry in the PRC: What Memories Are Being Passed On? A Case Study of Tongli, a Protected Township in Jiangsu Province. China Perspect. 2006, 67, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zunxin, B. A propos de la «fièvre de la fin des Qing». Peut-on comparer les ères de réformes des fins du XIXe et du XXe siècles? Perspect. Chin. 1995, 27, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.S. Wu Zhen; Zhejiang She Ying Chu Ban She: Hangzhou, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, R.G. Chinese Houses: The Architectural Heritage of a Nation; Tuttle Publishing: Singapore, 2005; pp. 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wuzhen Official Website. Available online: http://en.wuzhen.com.cn/web/introduction?id=2 (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- Ged, F. Protection du patrimoine et développement du tourisme: Quels enjeux pour quels territoires? Monde Chinois 2010, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.L.; Zan, L. Xi’an and Daming Palace. In Heritage Sites in Contemporary China. Cultural policies and Management Practices; Zan, L., Yu, B., Yu, J., Yan, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 110–145. [Google Scholar]

- Datong 2011. Available online: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/articles.php?searchterm=027_datong.inc&issue=027 (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- Berg, P.O.; Björner, E. (Eds.) Branding Chinese Mega-Cities: Policies, Practices and Positioning; Edward Elgar Pub: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, F. China’s Burra Charter: The formation and Implementation of the China Principles. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2007, 13, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehand, J.W.R.; Gu, K.; Whitehand, S.M. Urban morphology and conservation in China. Cities 2011, 28, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, D.B. Places for the gods: Urban planning as orthopraxy and heteropraxy in China. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2011, 29, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. La Naissance du Concept de Patrimoine en Chine, XIX-XXe Siècles; Éditions Recherches IPRAUS: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The Yangtze region was always of great economic importance to successive dynasties for its agricultural potential. The areas around the cities of Huzhou and Suzhou (situated respectively in the south and north east of Tai lake) and south of the Yangtze river, in Zhejiang province, due to their abundant watercourses, were the grain baskets of China. The Grand Canal was built, in fact, in order to transport grain from the Yangtze basin to the great northern capital cities. “The management of the Grand Canal was made possible over a long period by means of the Caoyun system, the imperial monopoly for the transport of grain and strategic raw materials, and for the taxation and control of traffic. The system enabled the supply of rice to feed the population, the unified administration of the territory, and the transport of troops.” [3]. |

| 2 | The reason why the recent inscription of the Grand Canal in the UNESCO WHS didn’t manage to promote a more in-depth historical analysis of the water towns and of their development is due, in our view, to the fact that the inscription was focused on the hydraulic importance of the Grand Canal works and of the archaeological excavations related to them, and not on the historical development of the sites and water towns developed along it [5]. |

| 3 | Fei Xiaotong [6] by conducting a series of surveys was the first to bring the attention back to these small urban centres. Ruan Yisan, instead, since 1986 was the first to focus on these towns’ historic urban heritage, promoting an alternative way to their development [7]. Within the Jiangnan region (literally meaning south of the river) may be identified more than one clusters of water towns, such as for example the one discussed in this article, or the one forming the Shaoxing Prefecture city (with a population of approximately 5 million in 2010) [8]. |

| 4 | Research on urban history, in general, is still lagging behind in China and in particular studies regarding urban physical form and morphology are as yet not well established [. One of the few well done works on the subject and relative to the city of Suzhou is [9]. |

| 5 | “Wealthy businessman or important government officials had big houses lying lengthways in ‘jin’ or transversely in ‘luo’” [4] (p. 111). |

| 6 | Awareness of the value of conservation research and legislation emerged in China in the 1920s. The Research Institute of Archaeology (Kaoguxue Yanjiusuo), is perhaps the earliest organisation to carry out research on conservation of the built environment, and was established in Yanjing University in 1922. But this tradition was greatly lost with the advent of Socialist China and more particularly with the 10 years of the cultural revolution and the movement for “destroying the old four” [23]. |

| 7 | In fact, many academics and teaching staff from architecture and urban planning schools in China are actively involved in conservation planning practice and theoretical research, as Professor Ruan Yisan, on whose professional work this paper is focusing. Regarding his theoretical research see: Wang, J., Ruan, Y.S. Historic City Conservation Theory (in Chinese), Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 1999; Ruan, Y.S., Lin, L. Authenticity in Relation to the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, in Urban Heritage Conservation, edited by College of Architecture & Urban Planning Tongji University, China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010, pp. 49–61; Shao, Y., Ruan Y.S. Evolution and Character of the Historical and Cultural Heritage Preservation Law in France, in Urban Heritage Conservation, edited by College of Architecture & Urban Planning Tongji University, China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010, pp. 143–152 [28]. |

| 8 | According to Maylis Bellocq these six small historic water towns “had submitted a joint application to be listed as a world heritage site and were included in the first national list of historic towns and are, since 2008, subject to the Regulation for the Protection of Historic Cities, Towns and Villages (Lishi Wenhua Mingcheng).” [11] (p. 5). According to Alain Marinos “La petite ville de Tongli, qui fait partie des six villes d’eau du Jiangnan pour lesquelles était projetée une demande d’inscription sur la liste du patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO, a été retenue. Les réalisations entreprises ont été primées à trois reprises, par le ministère chinois de la Construction en 2002 et par l’UNESCO dans la région Asie-Pacifique en 2003 et 2007” [35] (p. 19). |

| 9 | I am referring to the years of the cultural revolution and the movement for “destroying the old four”. |

| 10 | In the years between 1980 and 2010 Zhejiang province saw a population increase from 14% to 62%, compared to the national average increase of 50% [55]. |

| 11 | Professor Zhou Jian is currently also the Director of the World Heritage Institute for Training and Research for the Asia and the Pacific Region, under the auspices of UNESCO – WHITRAP. Available online http://www.whitr-ap.org/index.php?classid=1459 (accessed on 30 November 2018). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Porfyriou, H. Urban Heritage Conservation of China’s Historic Water Towns and the Role of Professor Ruan Yisan: Nanxun, Tongli, and Wuzhen. Heritage 2019, 2, 2417-2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030149

Porfyriou H. Urban Heritage Conservation of China’s Historic Water Towns and the Role of Professor Ruan Yisan: Nanxun, Tongli, and Wuzhen. Heritage. 2019; 2(3):2417-2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030149

Chicago/Turabian StylePorfyriou, Heleni. 2019. "Urban Heritage Conservation of China’s Historic Water Towns and the Role of Professor Ruan Yisan: Nanxun, Tongli, and Wuzhen" Heritage 2, no. 3: 2417-2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030149