Making Space for Heritage: Collaboration, Sustainability, and Education in a Creole Community Archaeology Museum in Northern Belize

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Project Background

3. Project Objectives

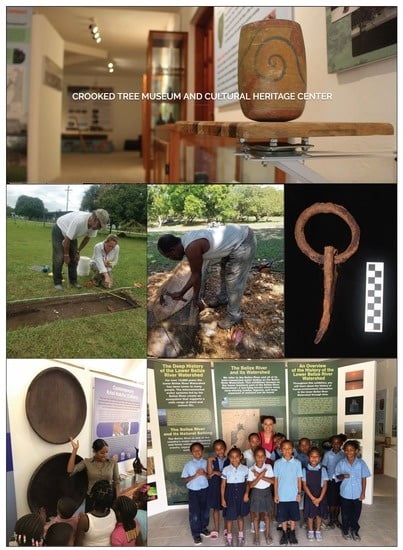

- Collaboration in archaeology and museum practice in partnering with local stakeholders;

- Sustainability in the cultural content and physical structure of the museum exhibition; and

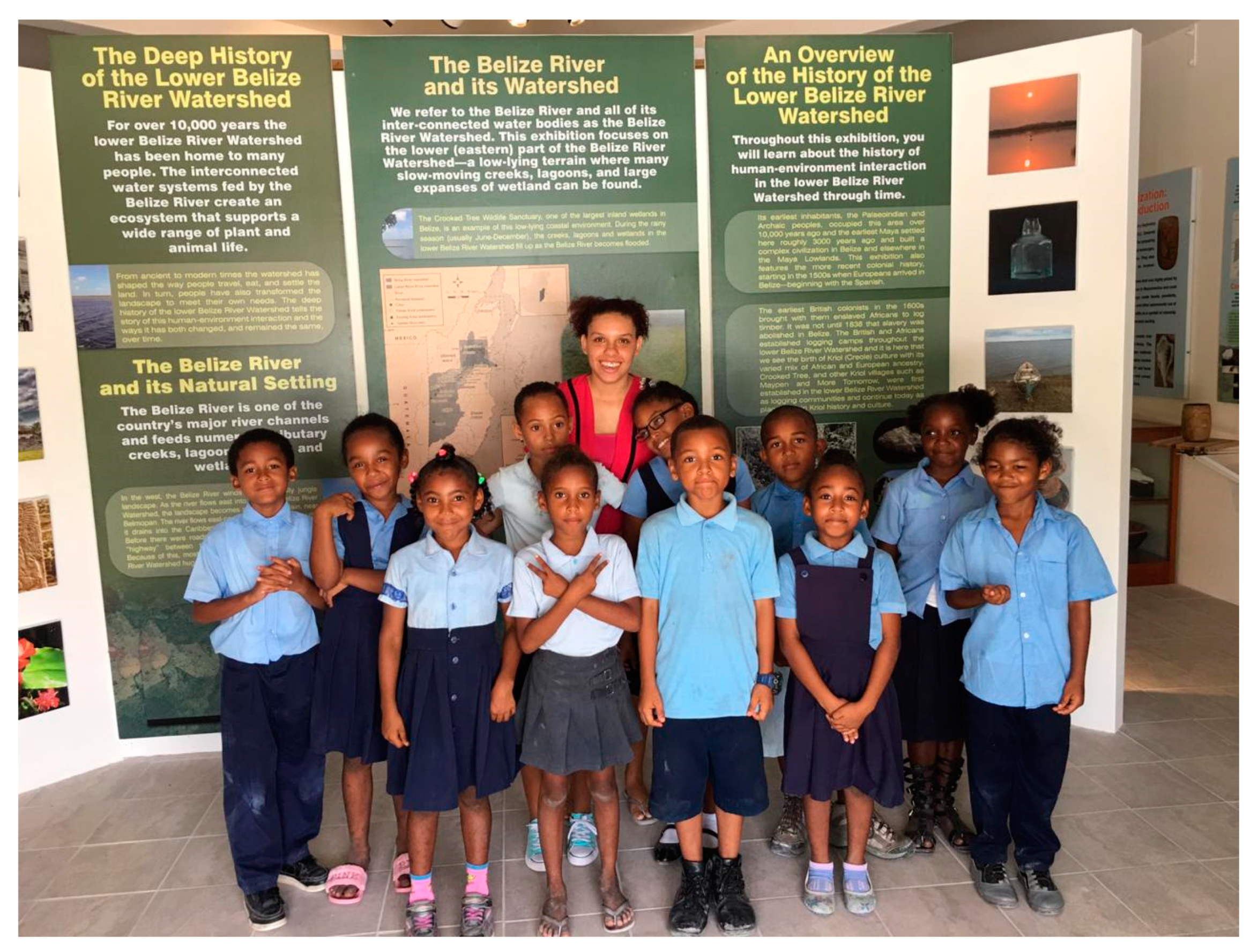

- Education geared for local school-age children with exhibition content and displays that complement the national social studies curriculum.

4. Developing Community Archaeology Museums “with, by, and for” Descendant Communities

5. Development of a Creole Community Archaeology Museum in Crooked Tree

5.1. Collaboration

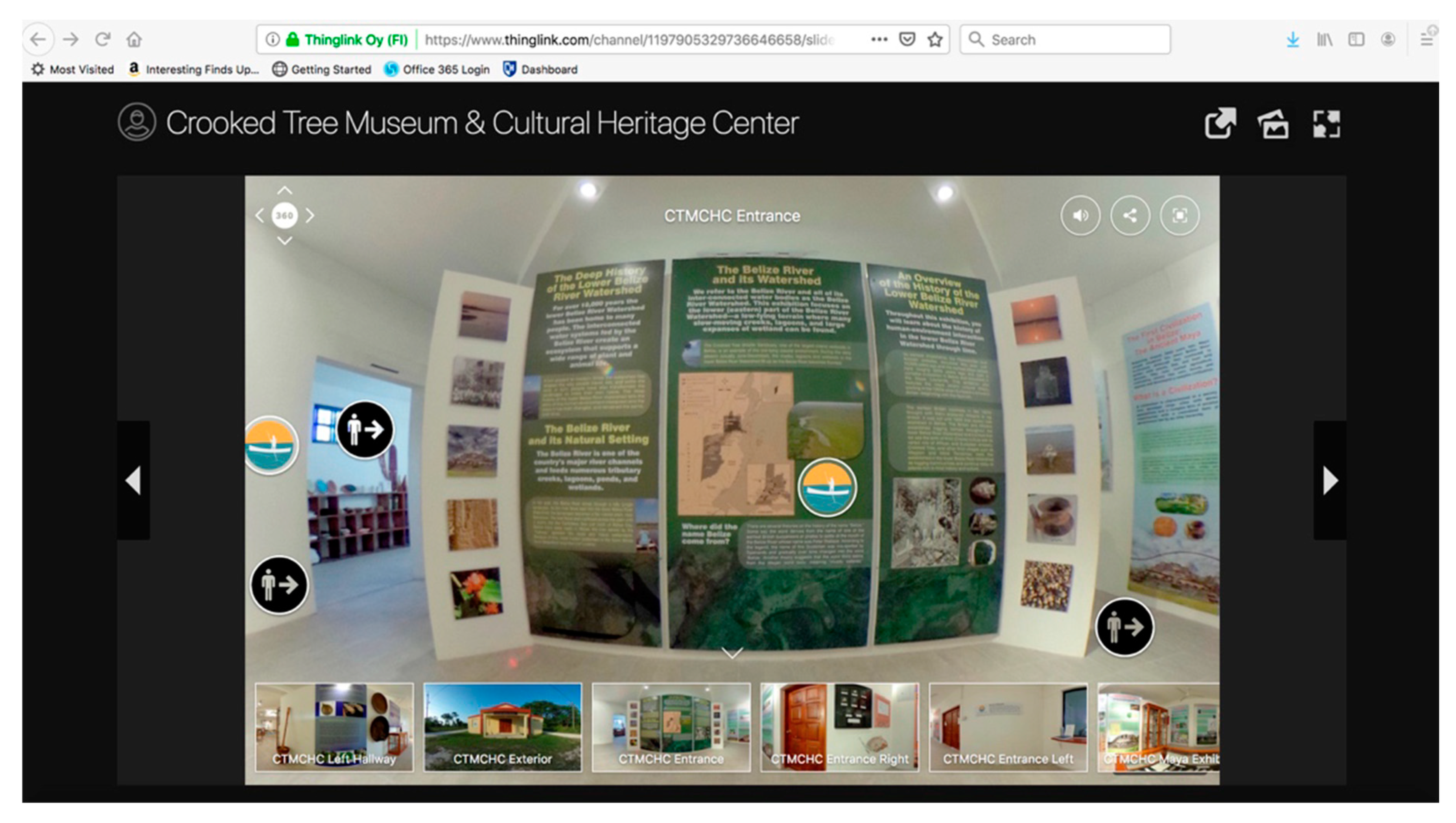

5.2. Sustainability

5.3. Education

6. Discussion

Ah waahn noa hoo seh Kriol noh ga no kolcha!....[I want to know who says Creoles have no culture!....]Ah waahn noa hoo seh Kriol noh ga no hischri!....[I want to know who says Creoles have no history!....]Leela Vernon [76]

7. Concluding Thoughts and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chambers, E.J. Epilogue: Archaeology, Heritage and Public Endeavor. In Places in Mind: Public Archaeology as Applied Anthropology; Shackel, P.A., Chambers, E.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Shakel, P.A. Working with Communities: Heritage Development and Applied Archaeology. In Places in Mind: Public Archaeology as Applied Anthropology; Shackel, P.A., Chambers, E.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ardren, T. Conversations About the Production of Archaeological Knowledge and Community Museums at Chunchucmil and Kochol, Yucatán, México. World Archaeol. 2002, 34, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ardren, T. Where are the Maya in Ancient Maya Archaeological Tourism? Advertising and the Appropriation of Culture. In Marketing Heritage: Archaeology and the Consumption of the Past; Rowan, Y., Baram, U., Eds.; Altamira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Magnoni, A.; Ardren, T.; Hutson, S. Tourism in the Mundo Maya: Inventions and (Mis)Representations of Maya Identities and Heritage. Archaeol. J. World Archaeol. Congr. 2007, 3, 353–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awe, J.J. The Archaeology of Belize in the Twenty-First Century. In The Oxford Handbook of Mesoamerican Archaeology; Nichols, D.L., Pool, C.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hutson, S.R.; Lamb, C.; Vallejo-Cáliz, D.; Welch, J. Reflecting on PASUC Heritage Initiatives through Time, Positionality, and Place. Heritage 2020, 3, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, W.E. Mayas in the Marketplace: Tourism, Globalization and Cultural Identity; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vitous, C.A. Impacts of Tourism Development on Livelihoods in Placencia Village, Belize. Master’s Thesis, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Buck, E.; Craig, J.H.; Murata, S. From Ancient Maya to Kriol Culture: Investigating the Deep History of the Eastern Belize Watershed. Res. Rep. Belizean Archaeol. 2017, 14, 353–361. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Buck, E.; Willis, M.; Murata, S.; Craig, J.H. Investigating Ancient Maya Settlement, Wetland Features, and Preceramic Occupation Around Crooked Tree, Belize: Excavations and Aerial Mapping with Drones. Res. Rep. Belizean Archaeol. 2018, 15, 307–317. [Google Scholar]

- Bolland, O.N. Colonialism and Resistance in Belize: Essays in Historical Sociology; Cubola Publishers: Benque Viejo del Carmen, Belize, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bonorden, B. Comparing Colonial Experiences in Northwestern Belize: Archaeological Evidence from Qualm Hill Camp and Kaxil Uinic Village. Master’s Thesis, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Buck, E.; Houk, B.A.; Kaeding, A.R.; Bonorden, B. The Strange Bedfellows of Northern Belize: British Colonialists, Confederate Dreamers, Creole Loggers, and the Caste War Maya of the Late Nineteenth Century. Int. J. Hist. Archaeol. 2019, 23, 172–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, O. View from the Periphery: A Hermeneutic Approach to the Archaeology of Holotunich (1865–1930), British Honduras. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.E.S. Excavations at San Jose, British Honduras; Publication No. 506; Carnegie Institution of Washington: Washington, DC, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Lonetree, A. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Onciul, B. Museums, Heritage and Indigenous Voice: Decolonizing Engagement; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.; Cubitt, G.; Wilson, R.; Fouseki, K. Representing Enslavement and Abolition in Museums: Ambiguous Engagements; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, A.E. Old Tings, Skelintans, and Rooinz: Belizean Student Perspectives about Archaeology. Chungara Rev. Antropol. Chil. 2012, 44, 475–485. [Google Scholar]

- Andres, C.R.; Pyburn, K.A. Out of Sight: The Postclassic and Early Colonial Periods at Chau Hiix, Belize. In The Terminal Classic in the Maya Lowlands: Collapse, Transition, and Transformation; Demarest, A.A., Rice, P.M., Rice, D.S., Eds.; University of Colorado Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2004; pp. 402–423. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Buck, E. Surveying the Crossroads in the Middle Belize Valley: A Report of the 2011 Belize River East Archaeology Project; Occasional Paper No. 5; University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Buck, E. Archaeology in the Middle Belize Valley: A Report of the 2012 Belize River East Archaeology Project; Occasional Paper No. 6; University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Buck, E. Investigations of the Belize River East Archaeology Project: A Report of the 2014 and 2015 Field Seasons Volume 1; Occasional Paper No. 7; University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Buck, E. Investigations of the Belize River East Archaeology Project: A Report of the 2016 and 2017 Field Seasons; Occasional Paper No. 8; University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Buck, E. Investigations of the Belize River East Archaeology Project: A Report of the 2018 and 2019 Field Seasons; Occasional Paper No. 9; University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pyburn, K.A. Pomp and Circumstance Before Belize: Ancient Maya Commerce and the New River Conurbation. In The Ancient City: New Perspectives on Urbanism in the Old and New World; Marcus, J., Sabloff, J.A., Eds.; School of American Research: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2008; pp. 247–272. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Buck, E.; Clarke-Vivier, S.; Kaeding, A.R.; Phillips, L. Public Archaeology in Belize: Cultural Sustainability and the Deep History of the Lower Belize River Watershed. Res. Rep. Belizean Archaeol. 2019, 16, 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- DeGennaro, J.; Kaeding, A.R. An Investigation of Colonial Artifacts at the Stallworth-McRae Site Near Saturday Creek. In Surveying the Crossroads in the Middle Belize Valley: A Report of the 2011 Belize River East Archaeology Project; Harrison-Buck, E., Ed.; University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 2011; pp. 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Buck, E.; Murata, S.; Kaeding, A.R. From Preclassic to Colonial Times in the Middle Belize Valley: Recent Archaeological Investigations of the BREA Project. Res. Rep. Belizean Archaeol. 2012, 9, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kaeding, A.R.; DeGennaro, J. A British Colonial Presence in the Middle Reaches of the Belize River: Operations 5 and 6. In Surveying the Crossroads in the Middle Belize Valley: A Report of the 2011 Belize River East Archaeology Project; Harrison-Buck, E., Ed.; University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 2011; pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, A.E. Dis da fi wi Hischri? Archaeology Education as Collaboration With Whom? For Whom? By Whom? Archaeol. Rev. Camb. 2011, 26, 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, A.E. Examining the Pedagogy of Community-based Heritage Work Through an International Public History Field Experience. Public Hist. 2018, 40, 54–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, A.E. Learning from Cultural Engagements in Community-based Heritage Scholarship. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 1068–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, S. Community-Based Archaeology: Research with, by, and for Indigenous and Local Communities; University of California Press: Berkley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, G.P. Education and Empowerment: Archaeology with, for and by the Shuswap Nation, British Colombia. In At a Crossroads: Archaeology and First Peoples in Canada; Nicholas, G.P., Andrews, T.D., Eds.; Archaeology Press: Burnaby, BC, Canada, 1997; pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Atalay, S. Indigenous Archaeology as Decolonizing Practice. Am. Indian Q. 2006, 30, 280–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDavid, C. Archaeologies that Hurt; Descendants that Matter: A Pragmatic Approach to Collaboration in the Public Interpretation of African-American Archaeology. World Archaeol. 2002, 34, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDavid, C.; Brock, T.P. The Differing Forms of Public Archaeology: Where We Have Been, Where We Are Now, and Thoughts for the Future. In Ethics and Archaeological Praxis. Ethical Archaeologies: The Politics of Social Justice; Gnecco, C., Lippert, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 159–183. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell-Chanthaponh, C.; Ferguson, T.J. Introduction: The Collaborative Continuum. In Collaboration in Archaeological Practice: Engaging Descendant Communities; Colwell-Chanthaphonh, C., Ferguson, T.J., Eds.; Altamira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2008; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.; Waterton, E. Heritage, Communities and Archaeology; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke, C. The Social Museum in the Caribbean: Grassroots Heritage Initiatives and Community Engagement; Sidestone Press: Lieden, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J.M.; Brandon, J.C. Descendant Community Partnering, the Politics of Time, and the Logistics of Reality: Tales from North American African Diaspora Archaeology. In The Oxford Handbook of Public Archaeology; Carman, J., McDavid, C., Skeates, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, in press.

- Faulseit, R.K. Managing Legacy in Oaxaca: Observations on the Development of a Community Museum in San Mateo Macuilxóchitl. Archaeol. Pap. Am. Anthropol. Assoc. 2015, 25, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyburn, K.A. Engaged Archaeology: Whose Community, Which Public? In New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology; Matsuda, A., Okamura, K., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. The Uses of Heritage; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, B.J.; Horning, A. Introduction to a Global Dialogue on Collaborative Archaeology. Archaeol. J. World Archaeol. Congr. 2019, 15, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, A. Making Histories of African Caribbeans. In Making Histories in Museums; Kavanagh, G., Ed.; Leicester University Press: London, UK, 1996; pp. 92–105. [Google Scholar]

- Price, R.; Price, S. Executing Culture: Musée, Museo, Museum. Am. Anthropol. 1995, 97, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnany, P. Maya Cultural Heritage: How Archaeologists and Indigenous Communities Engage the Past; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A.M.; Kosiba, S. How Things Act: An Archaeology of Materials in Political Life. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2016, 27, 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison-Buck, E. Maya Relations with the Material World. In The Maya World; Hutson, S., Ardren, T., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 424–442. [Google Scholar]

- Kosiba, S.; Janusek, J.W.; Cummins, T.B.F. (Eds.) Sacred Matter: Animacy and Authority in the Americas; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, R.M. From Enchantment to Agencement: Archaeological Engagements with Pilgrimage. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2018, 18, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodéhn, C. Democratization: The Performance of Academic Discourse on Democratizing Museums. In Heritage Keywords: Rhetoric and Redescription in Cultural Heritage; Samuels, K.L., Rico, T., Eds.; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2015; pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Agbe-Davies, A.S. Concepts of Community in the Pursuit of an Inclusive Archaeology. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyburn, K.A. Preservation as ‘Disaster Capitalism’: The Downside of Site Rescue and the Complexity of Community Engagement. Public Archaeol. 2014, 13, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, O.N. Creolisation and Creole Societies: A Cultural Nationalist View of Caribbean Social History. Caribb. Q. 1998, 44, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoman, A. Thirteen Chapters of a History of Belize; The Angelus Press: Belize City, Belize, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, A.E. Cultural Diversity: Cultivating Proud and Productive Citizens in Belizean Education. In Heritage Keywords: Rhetoric and Redescription in Cultural Heritage; Samuels, K.L., Rico, T., Eds.; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2015; pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. Becoming Creole: Nature and Race in Belize; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, S.W. Ethnicity and Ethnically “Mixed” Identity in Belize: A study of Primary School-Age Children. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 1998, 29, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, S.W. Ethnicity and Multi-ethnicity in the Lives of Belizean Rural Youth. J. Rural Stud. 2002, 18, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, S.R.; Herrera, G.C.; Chi, G.A. Maya Heritage: Entangled and Transformed. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, S.R. Dwelling, Identity, and the Maya: Relational Archaeology at Chunchucmil; Altamira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, M.P.; LaRoche, C.J.; Babiarz, J.J. The Archaeology of Black Americans in Recent Times. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2005, 34, 575–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakour, K.; Kuijt, I.; Burke, T. Different Roles, Diverse Goals: Understanding Stakeholder and Archaeologists Positions. Archaeol. J. World Archaeol. Congr. 2019, 15, 371–399. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Q. Community Archaeology and Alternative Interpretation of the Past Through Private Museums in Shanghai, China. Archaeol. J. World Archaeol. Congr. 2015, 11, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell-Chanthaphonh, C.; Ferguson, T.J. Trust and Archaeological Practice: Towards a Framework of Virtue Ethics. In The Ethics of Archaeology: Philosophical Perspectives on Archaeological Practice; Scarre, C., Scarre, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Carman, J. Educating for Sustainability in Archaeology. Archaeol. J. World Archaeol. Congr. 2016, 12, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gražulevičiūtė, I. Cultural Heritage in the Context of Sustainable Development. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2006, 3, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Loach, K.; Rowley, J.; Griffiths, J. Cultural Sustainability as a Strategy for the Survival of Museums and Libraries. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2017, 23, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciecko, B. 4 Ways Museums Can Successfully Leverage Digital Content and Channels during Coronavirus (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.aam-us.org/2020/03/25/4-ways-museums-can-successfully-leverage-digital-content-and-channels-during-coronavirus-covid-19/ (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Shulman, L.S. Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educ. Res. 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Lopez, P. Belize at Thirty: Epistemologies, Perspectives, Challenges and Implications for Change. In Educational Trends: A Symposium in Belize, Central America; Cook, P., Ed.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: London, UK, 2014; pp. 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon, L. Ah Wah Know Who Seh Creole No Gàh No Culture (I Want to Know Who Says Creoles Have No Culture). In Kriol Kolcha; Stonetree Records: Benque Viejo del Carmen, Belize, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Siegal, N. Many Museums Won’t Survive the Virus. How Do You Close One Down? Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/29/arts/design/how-do-you-close-a-museum.html (accessed on 24 May 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harrison-Buck, E.; Clarke-Vivier, S. Making Space for Heritage: Collaboration, Sustainability, and Education in a Creole Community Archaeology Museum in Northern Belize. Heritage 2020, 3, 412-435. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3020025

Harrison-Buck E, Clarke-Vivier S. Making Space for Heritage: Collaboration, Sustainability, and Education in a Creole Community Archaeology Museum in Northern Belize. Heritage. 2020; 3(2):412-435. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3020025

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarrison-Buck, Eleanor, and Sara Clarke-Vivier. 2020. "Making Space for Heritage: Collaboration, Sustainability, and Education in a Creole Community Archaeology Museum in Northern Belize" Heritage 3, no. 2: 412-435. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3020025

APA StyleHarrison-Buck, E., & Clarke-Vivier, S. (2020). Making Space for Heritage: Collaboration, Sustainability, and Education in a Creole Community Archaeology Museum in Northern Belize. Heritage, 3(2), 412-435. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3020025