Transfer of Development Rights and Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Case Study at Athens Historic Triangle, Greece

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The TDR Concept

3. Greece’s Legal Framework on Cultural Heritage Protection and TDRs

3.1. Cultural Heritage Protection and TDR in Greece: 1832–2007

3.2. Current Legal Framework on TDRs and Cultural Herritage Protection in Greece

- Legal and technical provisions on transfer receiving zones, zones of excess illegal constructions/buildings, officially declared for each municipality and by presidential decree;

- The Municipality Digital Urban Identity, an open-access official spatial database, where all relevant data on urban and spatial plans and building regulations are maintained and updated by each municipality;

- The Digital Land Bank, an open-access database for the issue, management, and exploitation of TDR Deeds, under the supervision of the Ministry for the Environment and Energy;

- The object of TDR is the transfer of building factor, abstracted from a building or property and superinduced to a recipient building or property;

- The TDR deed corresponds to the surface (in square meters) that is not allowed to be built on due to official administrative acts that limit construction and property exploitation. The transfer deed is exploitable for buildings/properties within the same municipality or a neighboring municipality or the same prefecture that has valid urban plans and valid transfer recipient zones. Recipient buildings fall into two categories: (i) buildings that exceed official (licensed or not) building regulations and (ii) buildings located within urban zones/areas of special construction/reconstruction.

4. Materials and Methods

- a.

- Identify the regulatory/protective legal framework on cultural heritage protection and especially the 3D restrictions on urban development for cultural heritage protection.

- b.

- Identify the current status (i) of property ownership and (ii) urban planning regulations.

- c.

- Identify the development of buildings that are incompatible with current urban planning regulations with respect to the regulatory framework on urban development during the period of their construction licensing and construction development.

4.1. Identification of Data Sets

- Property rights per se;

- Urban development regulatory frameworks, current and precedent, and the official licensing of stand-alone buildings;

- Official declarations of regulatory frameworks for cultural heritage protection, stand-alone listed buildings and places/settlements/city centers of great historic, traditional or architectural importance;

- Urban landscape spatiotemporal documentation via official aerial photos and stereopair.

4.2. 3D Definition of Properties Development Rights & Restrictions

4.2.1. Data on Land Parcels

4.2.2. Data on Urban Development, the Urban Environment and the Built Environment

4.2.3. Data on Cultural Heritage

4.3. Determination of 3D DRs and TDRs

- 3D actual constructed built-volume, fragmented to floors;

- 3D virtual development rights with respect to built-volume, fragmented to floors;

- 3D Transferable Development Rights with respect to built-volume, fragmented to floors.

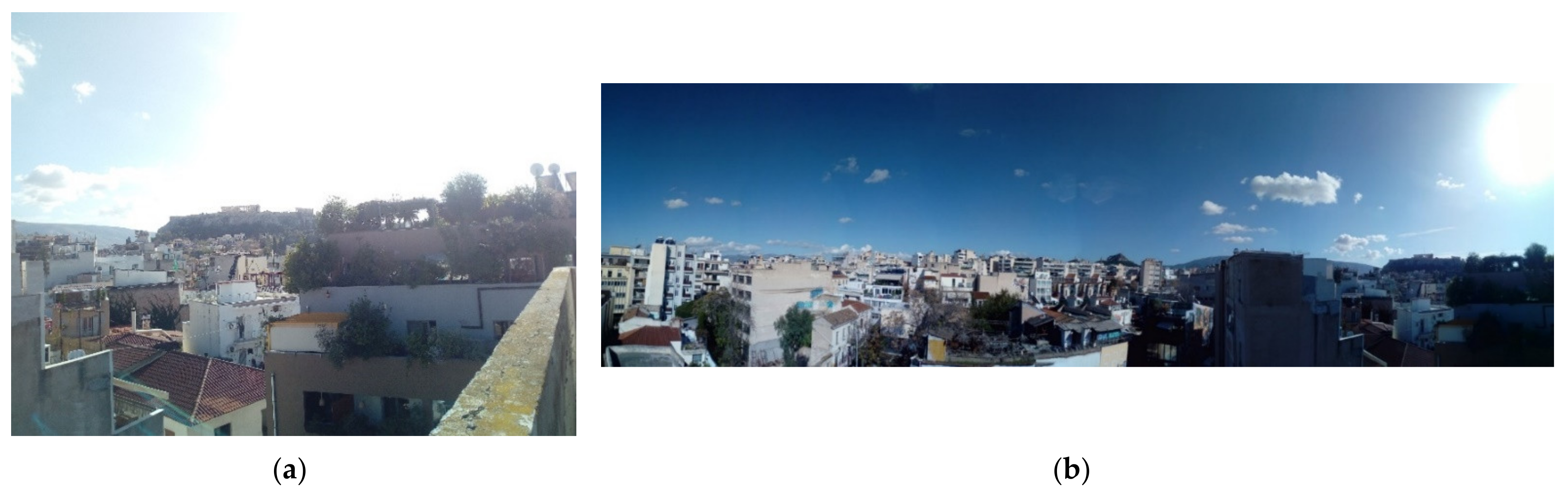

5. Case Study

Methodology Implementation

6. Results

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bongaarts, J. United nations department of economic and social affairs, population division world mortality report 2005. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2006, 32, 594–596. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-638-98.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- UNESCO THE HUL GUIDEBOOK. Managing Heritage in Dynamic and Constantly Changing Urban Environments, a Practical Guide to UNESCO’s Recomendation on the Historic Urban Land Scape. 2016. Available online: http://historicurbanlandscape.com/themes/196/userfiles/download/2016/6/7/wirey5prpznidqx.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Alchian, A.A.; Demsetz, H. The property right paradigm. J. Econ. Hist. 1973, 33, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, M.; Murtazashvili, I.; Murtazashvili, J. The politics of land property rights. J. Inst. Econ. 2020, 16, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeny, D.H. The Development of Property Rights in Land: A Comparative Study; Center Discussion Paper; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pratomo, R.A.; Samsura, D.; van der Krabben, E. Transformation of local people’s property rights induced by new town development (case studies in Peri-Urban areas in Indonesia). Land 2020, 9, 236. [Google Scholar]

- Beg, S. Digitization and Development: Property Rights Security, and Land and Labor Markets. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, J. Past, present, and future constitutional challenges to transferable development rights. Wash. L. Rev. 1999, 74, 825. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, T.L. The purchase of development rights: Preserving agricultural land and open space. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1991, 57, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.G. A proposal for the separation and marketability of development rights as a technique to preserve open space. J. Urb. L. 1973, 51, 461. [Google Scholar]

- Bengston, D.N.; Fletcher, J.O.; Nelson, K.C. Public policies for managing urban growth and protecting open space: Policy instruments and lessons learned in the United States. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Feiock, R.C. The Role of Local Governments in Open Space Preservation and Land Acquisition in Florida. In Growth Management and Public Land Acquisition: Balancing Conservation and Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; p. 143. [Google Scholar]

- Micelli, E. Development rights markets to manage urban plans in Italy. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act, CH. 53. HMSO. 1947. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1947/53/pdfs/ukpga_19470053_en.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Lloyd, G. Transferable Density in Connection with Zoning; Techical Bulletin 40; Urban Land Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, D.A. Development Rights Transfer in New-York-City; CT 06520; YALE LAW J CO INC 401-A YALE STATION: New Haven, CT, USA, 1972; Volume 82, pp. 338–372. ISBN 0044-0094. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, D.A. Transferable development rights-corrective, catastrophe, or curiosity. Real Estate Law J. 1983, 12, 26–52. [Google Scholar]

- Costonis, J.J. The Chicago Plan: Incentive zoning and the preservation of urban landmarks. Harv. L. Rev. 1971, 85, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costonis, J.J. The Disparity Issue: A Context for the Grand Central Terminal Decision. Harv. Law Rev. 1977, 402–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costonis, J.J. Development rights transfer: An exploratory essay. Yale LJ 1973, 83, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costonis, J.J. “ Fair” Compensation and the Accommodation Power: Antidotes for the Taking Impasse in Land Use Controversies. Columbia Law Rev. 1975, 75, 1021–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizor, P.J. Making TDR work: A study of program implementation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2007, 52, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, T.S. Introduction: From growth controls, to comprehensive planning, to smart growth: Planning’s emerging fourth wave. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2012, 78, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colavitti, A.M.; Serra, S. The transfer of development rights as a tool for the urban growth containment: A comparison between the United States and Italy. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2018, 97, 1247–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkous, E.R. Transfer of development rights in theory and practice: The restructuring of TDR to incentivize development. Land Use Policy 2016, 51, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Tang, B. Institutional change and diversity in the transfer of land development rights in China: The case of Chengdu. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, S.; Lu, B.; Nie, X. Overt and covert: The relationship between the transfer of land development rights and carbon emissions. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruetz, R.; Standridge, N. What makes transfer of development rights work?: Success factors from research and practice. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2008, 75, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.H.; Hou, J. Developing a framework to appraise the critical success factors of transfer development rights (TDRs) for built heritage conservation. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.C.; Pruetz, R.; Woodruff, D. The TDR Handbook: Designing and Implementing Transfer of Development Rights Programs; Island Press: Washington, WA, USA, 2013; ISBN 1-61091-159-8. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, V.; Walls, M. Policy monitor: US experience with transferable development rights. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2009, 3, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruetz, R. (Ed.) Beyond Takings and Givings: Saving Natural Areas, Farmland and Historic Landmarks with Transfer of Development Rights and Density Transfer Charges; Arje Press: Burbank, CA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0965831413. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R.A.; Madison, M.E. From land marks to landscapes: A review of current practices in the transfer of development rights. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1997, 63, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, A.; Stocker, L.; Payne, M.; Middle, G.J. Enabling managed retreat from coastal hazard areas through property acquisition and transferable development rights: Insights from Western Australia. Urban Policy Res. 2020, 38, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Guo, X.; Yin, W. From urban sprawl to land consolidation in suburban Shanghai under the backdrop of increasing versus decreasing balance policy: A perspective of property rights transfer. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 878–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkous, E.; Laurian, L.; Neely, S. Why do counties adopt transfer of development rights programs? J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 2352–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsnes, P.; Simons, G.P. Letting the market preserve land: The case for a market-driven transfer of development rights program. Contemp. Econ. Policy 1999, 17, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machemer, P.L.; Kaplowitz, M.D. A framework for evaluating transferable development rights programmes. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2002, 45, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, V. Property rights and the’transfer of development rights’: Questions of efficiency and equity. Town Plan. Rev. 2007, 78, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Gu, D.; Shahab, S.; Chan, E.H. Implementation analysis of transfer of development rights for conserving privately owned built heritage in Hong Kong: A transactions costs perspective. Growth Chang. 2020, 51, 530–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubukcu, K.M. The problem of fair division of surplus development rights in redevelopment of urban areas: Can the Shapley value help? Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BenDor, T.K.; Branham, J.; Whittemore, A.; Linkous, E.; Timmerman, D. A national inventory and analysis of US transfer of development rights programs. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakos, V. The Beginning of Greek Archeology and the Foundation of Athens Archeologicla Society; Athens Archeological Society: Athens, Greece, 2004; ISBN 960-8145-44-9. [Google Scholar]

- Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. Law on Antiquities; Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. On Amendments and Additions to 1899 Law on Antiquities; Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. Law on the State’s Monuments Restoration Service; Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. Law on the Protection of Buildings and Art Works Created after 1830; Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Perperidou, D.-G. Spatial Planning in Greece: From the Past to the Economic Crisis & the Future. In Proceedings of the FIG E-Working Week Smart Surveyors for Land and Water Management-Challenges in a New Reality, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 20–25 June 2021; Available online: https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2021/papers/ts08.4/TS08.4_perperidou_11177.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Hellenic Parliament. Hellenic Parliament Report on the Draft Act for Antiquities and Overall Cultural Heritage Protection; Hellenic Parliament: Athens, Greece, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Xatzivasileiou, E. Political Course: Expression of the need for “moving forward”. In Tzannis Tzannetakis, from Conssiousness to Action; Delivorias-Evanthis Xatzivasileiou, E., Ed.; Ekdoseis Polis: Athens, Greece, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. Law No 622 on the Revenues for Building Permint Approval and Other Provisions; Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. Law 3028 on Antiquities and Cultural Heritage Protection; Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. Law 880 on Maximum Building Factor Definition and Other Urban Planning Provisions; Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Council of State Decision 1310; Council of State: Athens, Greece, 1993.

- Council of State Decision 1073; Council of State: Athens, Greece, 1994.

- Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. Law 2300 on Tranfer of Building Factor and Other Provisions; Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Council of State Decision 2299; Council of State: Athens, Greece, 1996.

- Council of State Decision 4572; Council of State: Athens, Greece, 1996.

- Council of State Decision 6070; Council of State: Athens, Greece, 1996.

- Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. Law 3044 on Tranfer of Building Factor; Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Council of State Decision 2366; Council of State: Athens, Greece, 2007.

- Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. Law 4495 on Built Environmnet Protection and Other Provisions; Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2017.

- Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic. Law 4759 on Spatial and Urban Planning Modernization and Other Provisions; Official Government Gazette of the Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger, P. Altitudes of urbanization. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 100, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsson, J. Reasons for introducing 3D property in a legal system—Illustrated by the Swedish case. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasch, J.M.; Paulsson, J. 3D Property Research from a Legal Perspective Revisited. Land 2021, 10, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perperidou, D.-G.; Moschopoulos, G.; Sigizis, K.; Ampatzidis, D. Greece’s Laws on Properties and the Third Dimension: A Comparative Analysis; FIG: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; p. 13. Available online: https://fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2021/papers/ws_03.3/WS_03.3_perperidou_moschopoulos_et_al_11186.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Griffith-Charles, C.; Sutherland, M. 3D Cadastres for Complex Extra-Legal and Informal Situations. In Proceedings of the 6th International FIG Workshop on 3D Cadastres, Delft, The Netherlands, 2–4 October 2018; FIG: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; pp. 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Perperidou, D. Spatial and Descriptive Documentation of Land Parcels in Hellenic Cadastre: The Case of Mati and Kokkino Limanaki Areas; FIG: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2020/papers/ts03h/TS03H_perperidou_10387.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Theodoropoulos, P.; Perperidou, D.-G. Transfer of Development Rights & Cultural Heritage Protection: The Case of 3D Urban Implementation Plans; Department of Planning and Regional Development, University of Thessaly: Volos, Greece, 2019; pp. 441–452. [Google Scholar]

- Biris, K.H. Athens from 19th to 20th Century [In Greek: Ai Athinai, apo ton 18o Ston 19o Aiona], 5th ed.; Melissa Publishing House: Athens, Greece, 2005; ISBN 960-204-026-2. [Google Scholar]

| Data Set Authority | Data Set Description | Data Set Spatial Information | Data Set Descriptive Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hellenic Cadastre/ Land Registries | Deeds on land parcels/ land parcel geometrical description | 2D topographic diagrams and 2D cadastral diagrams, scale 1:500, 1:1000–1:2000 | Deeds with information on owners, property rights and deed transcription details |

| Hellenic Cadastre | Historic aerial photos andorthophotomaps | Printed or scanned or digital 2D aerial/satellite photos/ 3D stereopair | - |

| Ministry of Culture | |||

| Listed Buildings Department | Listed Buildings Declaration | 2D set of detailed and approved: topographic diagrams, scale 1:200/500/1000 top views, sections etc., scale 1:100, 1:200, 1: 500 | Declaration by presidential decree Protection status/regulations and restrictions Owners |

| General Directorate of Antiquities & Cultural Heritage | Archeological Sites Declaration | 2D maps, 1:2000, 1:5000 | Declaration by presidential decree Protection status/regulations and restrictions |

| National Archive on Monuments | Archeological cadastre, web GIS | Greek Heritage List, web database | |

| Ministry of Environment & Energy | |||

| Spatial Planning General Directorate | General Archive on Spatial Planning | 2D maps/diagrams on land use zones, scale: 1:5000 or less | Official approval decision by presidential decree or ministerial decision |

| Urban Planning General Directorate | Urban Planning Archive/e-poleodomia | 2D detailed maps on urban plans, urban zones, scale 1:500, 1:1000, 1:2000 | Presidential decree on building regulations and restrictions, Specifications on land uses |

| Urban Planning Directorate | Traditional Settlements Archive | 2D maps/diagrams prior to the 1923 settlements boundaries, scale 1:2000, 1:5000 | Presidential decree or regional authority decision on boundaries description, building regulations and restrictions Specifications on land uses |

| Urban Planning Directorate | Listed Buildings Archive | 2D set of detailed and approved: topographic diagrams, scale 1:200/500/1000 top views, sections, etc., scale 1:100, 1:200, 1: 500 | Declaration by presidential decree Protection status/regulation and restrictions Owners |

| Municipalities Building Authority | Official Approved Building Permits Archive | 2D set of detailed and approved: topographic diagram, scale 1:200/500/1000 top views, sections etc., scale 1:100, 1:200, 1: 500 | - |

| Hellenic Military Geographical Service | Historic and current aerial photos | Printed or Sand or Digital 2D/ 3D stereopair | - |

| Historic and current maps | 2D 1:5000/1:50000 |

| Cultural Heritage Protection Restrictions | Property Status | Restricted 3D Development Rights | 3D Transferable Development Rights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archeological Site Declaration | Built land parcel (legally)/fully in declaration area | Full property expropriation | 3D building total volume fragmented to floors |

| Built land parcel (legally)/partial in declaration area | Land parcel partition due declaration/partial property expropriation and remaining non-exploitable building factor | 3D building partial volume due to land parcel partition | |

| Unbuilt land parcel/fully in declaration area | Full property expropriation, including fully non-exploitable official building factor | 3D building total volume fragmented to floors (visualized) | |

| Unbuilt land parcel/partial in declaration area | Land parcel partition due declaration/partial property expropriation and non-exploitable remaining building factor | 3D building partial volume due to land parcel partition | |

| Listed-building | Listed-building/no permissible further construction | Non-exploitable remaining building factor | 3D building partial volume fragmented to upper floors |

| Listed-building/permissible further construction/restrictions due to building regulations (e.g., building land parcel coverage) | Non-exploitable remaining building factor | 3D building partial volume fragmented to upper floors | |

| Under cultural protection legislation urban area | No listed building/further construction development restrictions | Non-exploitable remaining building factor | 3D building partial volume fragmented to upper floors |

| No listed building over constructed due to precedent building regulation, before cultural protection restrictions enforcement | Floor expropriations for cultural heritage promotion | 3D building partial volume fragmented to upper floors |

| Plot/ Building No. | Characterization | Construction Period | Building Condition | Number of Floors | Constructed Building Factor | Constructed Building Surface (m2) | Constructed Building Height (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Listed building | 1880–1920 | Bad | 3 | 1.70 | 258.42 | 12.5 |

| 2 | Listed building | 1880–1920 | Good | 4 | 3.90 | 592.36 | 13 |

| 3 | Listed building | 1880–1920 | Good | 2 | 1.89 | 157.78 | 7 |

| 4 | - | 1960–1970 | Average | 5 | 3.33 | 453.93 | 15 |

| 5 | - | 1970–1980 | Average | 5 | 4.76 | 558.73 | 15 |

| 6 | - | 1960–1970 | Average | 7 | 5.50 | 2202.26 | 22 |

| 7 | Listed building | 1880–1920 | Average | 2 | 1.68 | 308.16 | 10.5 |

| 8 | - | 1970–1980 | Average | 7 | 4.76 | 876.46 | 22 |

| 9 | Listed building | 1880–1920 | Bad | 2 | 0.92 | 180.82 | 12.9 |

| Plot/ Building No. | Constructed Building Factor/ Official Maximum Building Factor | Constructed Building Height/ Official Maximum Building Height (m) | Total Constructed Building Surface/ Official Maximum Building Surface (m2) | Constructed Floors Number/ Official Maximum Floors Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −0.30 | 1.5 | −46.34 | 0 |

| 2 | 1.90 | 2 | 288.86 | 1 |

| 3 | −0.11 | −4 | −8.88 | −1 |

| 4 | 1.33 | 4 | 181.51 | 2 |

| 5 | 2.76 | 4 | 324.11 | 2 |

| 6 | 3.50 | 11 | 1400.86 | 4 |

| 7 | −0.32 | −0.5 | −59.06 | −1 |

| 8 | 2.76 | 11 | 508.42 | 4 |

| 9 | −1.08 | 1.9 | −213.42 | −1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perperidou, D.-G.; Siori, S.; Doxobolis, V.; Lampropoulou, F.; Katsios, I. Transfer of Development Rights and Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Case Study at Athens Historic Triangle, Greece. Heritage 2021, 4, 4439-4459. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040245

Perperidou D-G, Siori S, Doxobolis V, Lampropoulou F, Katsios I. Transfer of Development Rights and Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Case Study at Athens Historic Triangle, Greece. Heritage. 2021; 4(4):4439-4459. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040245

Chicago/Turabian StylePerperidou, Dionysia-Georgia, Stavroula Siori, Vasileios Doxobolis, Fotini Lampropoulou, and Ioannis Katsios. 2021. "Transfer of Development Rights and Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Case Study at Athens Historic Triangle, Greece" Heritage 4, no. 4: 4439-4459. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040245

APA StylePerperidou, D.-G., Siori, S., Doxobolis, V., Lampropoulou, F., & Katsios, I. (2021). Transfer of Development Rights and Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Case Study at Athens Historic Triangle, Greece. Heritage, 4(4), 4439-4459. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040245