Abstract

Despite church bell ringing being directly influenced by purposive human action, often as a liturgical function, it creates a community soundscape with ascribed heritage values. While general heritage management processes and decisions are informed by heritage professionals with a broader range of experience, we find that church bell ringing is contrary to this process. The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated how a stochastic disruptive event can dramatically alter soundscapes on a community-wide scale. Here, the effective power over bell ringing often rested with the individual clergy at the local level and is subject to that individual’s personal preferences. This has serious implications to non-traditional forms of heritage, such as intangible sounds and soundscapes. In realizing the value of sound signals and soundmarks, we highlight the need to formally recognize these sounds of religious settings and consider them in heritage frameworks.

1. Introduction

By their nature, religions and the beliefs that underpin them are intangible concepts that are transmitted inter- and intra-generationally. As such then, they form part of the intangible elements of humanity’s cultural heritage. Religions also manifest themselves as material objects in tangible form, through symbols (e.g., cross, fish), ritual objects (e.g., incense burner, prayer wheels), structures (e.g., mosques, temples), written documents (e.g., Torah, Koran), and communication devices (e.g., gongs, bells).

These tangible manifestations have attracted the attention of heritage management professionals and are actively being curated in their object form in museums, libraries, and archives and in their structural form through heritage listings and planning controls. In addition to the spiritual concepts that define religions, their practice is often associated with intangible aspects of ritual that can be experienced by participants irrespective of their spiritual attachment. This includes the sensory perceptions of sight (e.g., candles), smell (e.g., incense), sound (e.g., singing, bell ringing), touch (e.g., vibrations caused by organ music), and taste (e.g., communion wine). While central to ritual practice, usually within the confines of religious buildings, such multisensory experiences have only recently been considered by heritage professionals [1,2,3,4,5].

There is another aspect of intangible cultural heritage that is directly associated with religious material culture but that has community-wide relevance, irrespective of whether community members engage with religious practice: the ringing of church bells, which effects religious soundscapes in a community.

What follows is a conceptual paper that examines the nature of the soundscapes generated by bell ringing and the role played by priests as ‘managers’ of this aspect of cultural heritage. It will show that the effective power over church bell ringing and therefore over the resultant soundscapes rests with individual clergy at the local level.

As such then, this paper does not follow the standard IMRAD pattern of research papers, but will first discuss the nature of spiritual soundscapes in the community and then, using a case study in New South Wales (Australia), will describe the effects of COVID-19 on silencing these soundscapes. Following a description of the Heritage Management Process in NSW, this paper will examine the nature of decision-making with regard to bell ringing within the denominations and will assess the decisions taken by churches in this state during the recent COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, we will briefly look at the effect of the pandemic on soundscapes and explore how the decisions undertaken during this event operated dissimilarly to standard heritage management processes. It will conclude with a discussion of the implications of the power of individual clergy figures on shaping the audible manifestations of the heritage of their communities beyond the confines of their spiritual domain and then highlight implications for future management.

2. Spiritual Community Soundscapes

Living in villages, towns, and cities, people are immersed in acoustic environments comprising sounds that may be ancillary, i.e., derive from activities (e.g., factory sounds, sounds emerging from traffic) [6,7,8], or intentional, i.e., sounds designed to alert the public to dangers (e.g., car horns or sirens) or as public notifications [9,10]. The resulting soundscapes are perceived and experienced by individuals and groups within social contexts [11,12]. Previous research has investigated sounds and soundscapes associated with religious spaces, including churches, mosques, and temples, from a diversity of religious faiths [13,14,15,16,17,18]. A theoretical exploration of sounds and soundscapes and their general role in cultural heritage had been presented elsewhere [19,20] and need not be repeated here.

Examples of intentional notification sounds are bells, be they ships’ bells ringing the time or bells rung in a church tower calling the faithful to attend religious services [10,21,22]. Soundscapes are dynamic and undergo changes concurrent with technological advancements and patterns of the underlying human activity alongside societal changes (e.g., noise pollution ordinances) [20,23].

Unlike soundscapes that are a by-product of human activity and that are thus sensitive to technological changes [19], church bell ringing creates a soundscape that is directly influenced by purposive human action. Elsewhere, the authors have shown the myriad of values imparted by society on church bell ringing in NSW, being both religious and secular in origin [24]. These include values attributed to the tradition and sacred embodiment of bell ringing in liturgical function; as a memory trigger of significant events from a person’s individual history such as the end of World Wars, royal coronations, births, deaths, and marriages; and community heritage values based on the historical ringing of church bells within a certain parish or town. While church bells were ubiquitous until the mid-twentieth century and could be found in many Christian churches if the congregational finances allowed it, societal change in the post-World War II era has seen a decline in bell use and bell installation in recently consecrated churches [21].

Historically, the use of bell ringing has had some sort of backlash presented against it [10], and judging by media reports, there is a continued discontent among residents living near religious premises, with noise complaints about bell ringing on record, inter alia, from places as diverse as England, France, South Africa, and the USA. Some of these complaints have led to the silencing of bells via local ordinances or court decisions, such as in England, Ireland, and Italy [24]. In the Australian, setting this has occurred in Brisbane (Qld) [25] and Sydney [26]. The way that organizations respond to conflict issues such as discontent could therefore be important if sounds such as these are deemed to have heritage importance to some part of the community.

3. COVID-19 and Spiritual Soundscapes

Soon after its existence became public in late January 2020, COVID-19, the disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [27], rapidly developed into a global pandemic. At each national level, government reactions to curb or slow the progress of COVID-19 have involved, to various degrees and durations, the limitation of international arrivals to repatriation flights, limitations to domestic travel, the temporary shut-down of non-essential businesses, and the restriction of human movement during periods of ‘lockdown’ [28,29,30].

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated how a stochastic disruptive event can dramatically alter soundscapes on a community-wide scale. Following the first case of community transmission in Australia on 2 March 2020, the NSW State Government began to implement staged, community-wide public health control plans, placing restrictions on gathering and movement [31,32]. By 23 March, all churches were closed, and effective 31 March 2020, all of NSW was under Stage 3 lockdown, with public gatherings limited to two persons, and people were not permitted to leave their place of residence without reasonable excuse [33]. With the reduction in ambient transportation noises due to the reduction in human activity during the lockdown period, primarily a reduction in aircraft, vehicular traffic, and construction sounds [34], any ringing of church bells created a stronger audible presence than otherwise. In other cases, the termination of church bell sounds made the COVID-19 silence even more pronounced [35].

With reference to altered church bell ringing during the pandemic, similar decisions restricting bell ringing frequency and intensity due to noise complaints are usually Local Government planning determinations; they are not ad hoc but are instead based on extended community consultation. Given that soundscapes are one of the manifestations of a community’s cultural heritage [36,37,38,39], we have to ask who had the authority to make these decisions altering the church bell ringing occurrence during the COVID-19 lockdown period and on which basis they were made. Firstly, however, we will present a brief overview of current heritage management processes operating in NSW before exploring the actual decision-making that occurred during the pandemic.

4. The Heritage Management Process in NSW

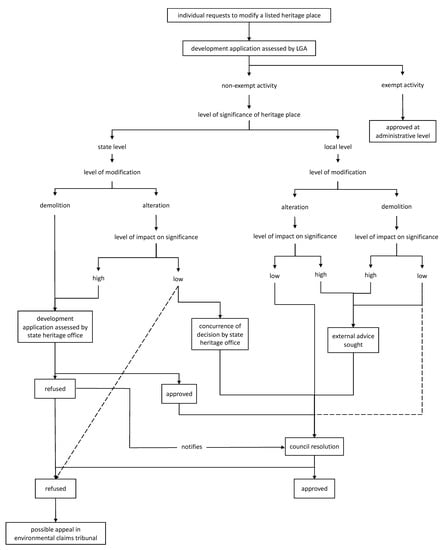

As in other jurisdictions in Australia [40,41] and beyond [42,43], the management of cultural heritage places and assets in NSW is highly regulated through formal processes governing nomination and heritage listing as well as modification or destruction (Figure 1). The NSW Heritage Office has published a number of guidelines under the Heritage Act 1977 [44] governing the research, assessment, nomination, and listing of heritage places [45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. The nomination and listing process is commonly carried out through community-based heritage studies [52], which have their own problems in the composition of community heritage panels and inter-generational memory effects [53]. While all heritage assets have site management plans in theory, this is rarely the case, particularly when disaster management plans are concerned, and often, asset protection plans are formulaic with the uncritical copying of content [54]. Where heritage-listed places are to be substantially altered or demolished beyond actions covered by standard exemptions [55], the Local Government Authority (LGA), as the permitting body, commonly seeks external advice, requesting that heritage studies and impact assessments be prepared [56,57], which are often associated with further documentation prior to and during demolition. This formal process applies to all heritage assets listed in the compiled Local Environmental Plan and is subject to the provisions of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act (1979) [58] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Generalized process chart for the legal modification or destruction of a heritage-listed place in New South Wales.

While the above relates to NSW, similar processes exist in all jurisdictions that maintain heritage registers or heritage lists. Of critical significance in this process is the fact that all decisions, while informed by heritage professionals in their advisory or project management capacity, are based on review, commonly by committees with a broader range of experience [53]. By and large, this dilutes the decision-making power of individuals and ensures that a greater range of views is heard and informs the decisions.

5. Bell Ringing Decision-Making within Major Denominations of Australia

The ringing of church bells falls into two categories, which are subject to different decision-making processes and authorities: bells being rung for liturgical reasons and bells being rung as community service, e.g., to audibly commemorate specific events (such as ANZAC Day). In both the Anglican and the Roman Catholic churches, decision-making is a largely hierarchical process, whereas among Presbyterian and Uniting Churches, the individual pastors have more autonomy over the more ‘ornamental’ aspects of the church.

In the Roman Catholic tradition, doctrine is determined by the Pope and is locally enabled by the various Archdioceses in Australia, while liturgical practice as well as the administration of the church is globally directed through the Canon Law [59] and regulated through the Breviarium Romanum [60] and the Missale Romanum [61]. These only regulate the ringing of the sanctus handbells during mass, but not the public ringing of tower bells. The decision-making power of whether and how often bells are to be rung seems to rest with the Parish priest, unless otherwise directed by the bishop.

In the Anglican tradition, doctrine is determined by the Archbishop of Canterbury and locally enabled by the General Synod of Australia, while liturgical practice is largely determined by the Diocese though the bishop and the General Synod of the Diocese [62]. The Diocese also regulates the administration of its constituent parishes through ordinances (e.g., [63]). A perusal of the various guidelines and ordinances showed them to be silent regarding the practice of bell ringing. Thus, the decision-making power of whether and how often bells are to be rung seems to rest with the Parish priest, unless otherwise directed by the bishop. While there are no universal directives that have been formally published by the any of the Synods, for those dioceses practicing Anglicanism on the ‘higher’ end, bell ringing is still directed by the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which stipulates that ‘the curate that ministreth in every parish church… shall cause a bell to be tolled there unto a convenient time before he begin; that the people may come to hear God’s word, and to pray with him’ [64].

In the Presbyterian tradition, doctrine is fundamentally determined by the respective synod, which exercises doctrine and liturgical authority over the presbyteries, which themselves are made over local churches. In terms of governance, local churches are governed by a body of elected elders (‘session’), which, in turn, elects the leadership of the respective presbytery, which, in turn, elects the synod. In Australia, the synods in each of the various states form the respective state church, with the Presbyterian Church of Australia being the peak body as a federation of State Presbyterian Churches formed in 1901. The synods, through their state churches, have voluntarily ascribed the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of Australia the authority to guard the doctrine of the Church and its practice of Church worship and discipline. The use of bells is not specified in the Book of Common Order of the Presbyterian Church of Australia [65].

The Uniting Church of Australia is derived from the 1977 union of the Congregational Union of Australia, the Methodist Church of Australasia, and sections of the Presbyterian Church of Australia. Consequently, its structure has much in common with its predecessors, using congregations, bodies of elected elders, presbyteries, and synods [66]. The use of bells is not specified in church directives for prayer and liturgy and seems to be at the discretion of the individual pastors [67].

6. Decisions Taken under COVID-19 Conditions

The decision making to alter the sounds of church bells is unique, and the COVID-19-induced changes to urban soundscapes have brought to the fore the role and power of the individual priest and bell-ringer. Some clergy acquiesced to the situation and embraced the physical shutting down of services as the new reality, pausing all church bell sounds in the process. For others, however, COVID-19 enkindled a sense of defiance, whereby the ringing of the bells was construed as a public signaling system to alert the community of the continued presence of the church [35]. While decisions regarding church operations during the pandemic reflected government directions as expected, the occasions whereby bell ringing procedures were altered as a result of decisions undertaken at the local or diocesan church level are important to explore, as they highlight how the management of certain types of intangible heritage diverge from the current management processes.

When, on 23 March 2020, all churches were closed as part the NSW government response to contain the spread of COVID-19 [33], Roman Catholic church authorities responded by developing or activating response plans [68] that reflected the changing government provisions [69] as well as innovative solutions, such as preaching in the open from the steps of the churches [70]. When the anticipated Stage 3 lockdown was announced by the NSW government on 30 March 2020 [71], the Catholic Archdiocese of Sydney activated its own response plan aimed at ensuring that liturgical services could be provided during lockdown [72]. The diocese specifically directed that the bells be rung five times each day at specific points in time, ‘calling on the faithful to unite in a prayer for an end to the COVID-19 pandemic’ [73]. In particular, the Catholic Archbishop posited that ‘the ringing of the bells will remind the faithful of the importance of pausing and uniting wherever they are in prayer for those suffering due to the coronavirus.’ The bells were to be rung according to the following schedule:

| 9 am: | Prayer for those infected with COVID-19 and all those who are sick. |

| 12 pm: | Angelus prayer for health professionals, clergy, and all those caring for the sick. |

| 3 pm: | Prayer for the unemployed, financially stressed, isolated, or lonely due to COVID-19. |

| 6 pm: | Prayer for the people of Australia and especially our political leaders and health authorities. |

| 9 pm: | Prayer for those who have died from COVID-19 and their families [73]. |

Once church services gradually resumed, bell ringing was no longer mentioned in the pastoral letters [74,75,76]; however, the physical activity of bell ringing continued to be restricted/regulated from 1 July 2020 by the requirement of a COVID-19 safety plan [77,78].

As discussed earlier, in the case of the Catholic Church, bell ringing depends on the personal interests and stance of the bishop, with most bishops being ‘somewhat detached from such concrete realities’ [79]. In traditional country churches, bells are therefore rung at the discretion of the parish priest, commonly at 6 am, 12 noon, and 6 pm, especially when this can be automated [79], either through programmed mechanical ringing of the (main) bell or via broadcasting a sound recording. The COVID-19 pandemic created an exception for the Diocese of Sydney, with its mandatory bell ringing, but this did not translate to action in other dioceses. Indeed, other Catholic congregations fell silent during lockdown. Some Catholic churches, such as Albury [80] and Leeton [81], not only stopped calling mass (as it was temporarily halted), but also stopped ringing the Angelus. Consequently, it was noted that ‘[d]uring the lock-down, it was quiet and unusual’ [80].

Like in the Catholic tradition, Anglican bishops by and large do not involve themselves in the operational management of local churches and thus leave decisions on the nature and extent of bell ringing to the local priest. As one priest noted, ‘[t]he bishop only comments when they ask for bells to ring normally at lunchtime to signify solidarity with refugees or COVID or some other cause. Parish council is only involved if there is a letter of complaint or a financial implication’ [82].

During the NSW lockdown period, the Anglican Diocese of Bathurst declared all church properties out of bounds, which effectively silenced all bell ringing in that diocese where bell-ringers operated the bells [83], while those that were automated or where a priest lent an active hand, continued to ring their bells. This was the case in Mudgee, for example, which rang its bells daily seven times at 7 pm [84]. This church also rang its bells on special occasions, such as in support of frontline COVID workers and for ANZAC Day [84]. In the Anglican Diocese of Armidale on the other hand, bell ringing was not restricted, with some churches increasing their audible presence. Examples are the Anglican churches in Moree [85] and Glen Innes, with the daily ringing at 9 am in an attempt to comfort those confined to quarantine, before returning to the typical pattern of bell ringing once restrictions lifted [86]. These examples show that despite the government directives to limit church operations during the pandemic, it was the power and the determination of the priest that allowed the continuation of bell ringing.

For some churches (e.g., St Matthew’s Anglican church in Albury), the required social distancing floor ratio of one person per four square metres [87] meant that the ringing chamber in the tower was too small, which made the ringing of peals impossible, even after the strict lockdown was lifted [88]. Manual ringing of the tenor bell remained possible but was dependent on the availability and the personal commitment of the priest [82]. Other churches with smaller crews could resume change ringing as soon as the strict lockdown was lifted [89] as well as continue to toll a single bell each Sunday. As the tower captain for St. John’s Anglican Church in Wagga Wagga noted, ‘[i]t broke my heart to think of the bells going silent, hence my motivation to toll through the enforced silence…I have previously rung for every conceivable celebration and the only times I know of bells being silenced has been during war. Our clergy informed me that it meant a lot to hear the bells ringing out, even through the shut down’ [89].

While most churches returned to normal bell ringing as soon as, or very soon after, the lockdown was lifted, the silence remained prolonged in some instances. The Anglican Church in Tamworth, for example, did not resume services and thus bell ringing until mid-August 2020 (146 days of silence) [90]. For example, as a consequence of COVID-19, the tenor bell of the Uniting Church in Albury, which until then had been rung every Sunday, fell silent [91] and did not resume until mid-October 2020 [92].

7. Conclusions

As has become clear in the previous discussion, despite the obvious termination of church services due to government directives, the effective power over religious soundscapes generated by the church bells often rests with the individual clergy at the local level. Fundamentally, whether bells are rung or not is subject to both the community-political and spiritual position of the individual member of the clergy unless specifically overridden by the bishop (in the Catholic and Anglican churches) or the body of elected elders (in the Presbyterian and Uniting churches). Clearly, individual clergy make specific choices. As Parker and Spennemann [24] have shown, some priests tend to second-guess how the bell ringing might be perceived by the surrounding community and, for fear of avoiding noise complaints, unilaterally reduce the number of occasions and the duration of bells being rung. The view of individuals can be quite opinionated and often with disparate attitudes on the action of bell ringing, and significantly, bell ringing practice can alter with the installation of a new priest [24]. A survey of bell ringing practices in New South Wales found that, overall, Anglican, Uniting, and Presbyterian clergy tend to attribute a lower significance to bell ringing than wardens, the church council, or the congregation [21]. Only among Roman Catholic clergy does bell ringing hold a considerable level of significance. Thus, if the authority for bell ringing rests with the clergy, then these personal values and the personal levels of significance attributed to ringing will make themselves, quite literally, heard.

COVID-19 brought this issue to the fore, when normal practices were disrupted by government lockdown stipulations. In many cases, it was solely the agency of individual clergy, or the commitment of lay bell-ringers, that determined whether the soundscapes were maintained, enhanced, or silenced. Added to this, the fact that the human activity sounds were reduced due to lower levels of traffic and construction activity made the presence or absence of religious bell sounds even more pronounced [35].

That the effective power over soundscapes generated by the church bells rests with the individual clergy at the local level has serious implications well beyond the individual congregation. Without doubt, the ringing of church bells contributes to the soundscape of a community and thus should be regarded as part of a community’s cultural heritage [19,21]. Unlike with other cultural heritage assets, where there is a formal multi-layered process to assess the adverse impact of any proposed activity (see Figure 1), it is the power of a single clergy, who are untrained in issues of heritage management, that can make these decisions. Moreover, these decisions are made primarily with liturgical, spiritual, and community relationship considerations in mind. While many priests recognize the value of church bell ringing to heritage and often regard the significance to heritage higher than the significance to liturgy or the congregation [24], that does not tend to figure in the personal decision-making framework. In situations where individual clergy are ambivalent or prevaricating, bell-ringers and vergers may take unilateral action and keep bells ringing, but again, their decision making is personally motivated without formal training in heritage issues.

Much of the heritage profession, in particular its practitioners, is focused on the tangible manifestations of heritage. Thus, much thought is given to the preservation and conservation of religious structures as well as objects associated with religious ritual. More generically, bells as objects of material culture have been the focus of attention, largely because they are imbued with symbolism, for example, as defining entities of ships or as political statements. Examples for the latter are the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia and its association with the founding of the American Republic [93] or the Freiheitsglocke (Freedom Bell) of West Berlin, being an audible symbol in the struggle between the capitalist, ‘free’ West and a communist, ‘oppressed’ East [94]. Many communities experienced a profound loss when the bells of their churches were requisitioned for their metal value during World War I and World War II.

Bell ringing in its liturgical and spiritual setting is a good example that demonstrates that cultural heritage cannot be reduced exclusively to the material object without incurring a loss. Indeed, setting aside campanologists and other aficionados, the materiality of the bell does not matter to the general public. The overwhelming majority of church bells are placed inside belltowers to be heard, not seen. For the communities that lost their bells, it was not the loss of the material object of a bell that was mourned, but the loss of what the bell provided: the familiar soundscape of community life. Throughout history, there are ample examples where the political powers of the day prohibited bell ringing and thus literally and symbolically silenced undesirable voices in the community. By the same token, bell ringing became a symbol of resistance, and its formal resumption a symbolism of regained freedoms.

At this point in time, there is no community consultation as to whether bells are rung or not. As noted, decisions are made by individuals, primarily with liturgical, spiritual, and community placation (response to noise complaints) considerations in mind. For clergy, there is no requirement to engage with their own congregation let alone with the wider community as to the benefits derived from the soundscape. Clearly, there is need to engage in wider community debate, which will need to occur on a parish-by-parish basis.

In the longer term, consideration should be given to formally recognize the community value of religious bell ringing as signal sounds or soundmarks in urban areas and include them in formal heritage frameworks. The theoretical discussion of this has commenced [19,20] but has not yet permeated into formal assessment procedures. In the meantime, there is an urgent need to include the various church hierarchies in that debate as well to ensure that individual clergy are cognizant of the community soundscape implications of their decisions concurrent with liturgical function and practice.

Author Contributions

Both authors have contributed equally to the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Spennemann, D.H.R.; Parker, M. The changing face of German Christmas Markets: Historic, mercantile, social and experiential dimensions. Heritage 2021, 4, 1821–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Choi, T.; Choi, Y.-S.; Jang, I.-S.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.-S. Multisensory Capture System for the Preservation of Traditional Painting. In Proceedings of the 2019 21st International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), Pyeong Chang, Korea, 17–20 February 2019; pp. 467–470. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, O.; Donaldson, J. Haptic heritage and the paradox of provenance within Singapore’s cottage food businesses. Food Cult. Soc. 2021, 25, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergin, N. The Fragrance of the Divine: Ottoman Incense Burners and Their Context. Art Bull. 2014, 96, 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyndham, C. A Careful Balance: Materialist Concern Meets Spiritual Function in Balkh, Afghanistan. Mater. Relig. 2019, 15, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guastavino, C. The ideal urban soundscape: Investigating the sound quality of French cities. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2006, 92, 945–951. [Google Scholar]

- Colombijn, F. Toooot! Vroooom! The urban soundscape in Indonesia. Sojourn 2007, 22, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, F.; Zannin, P.H.T. Assessment of railway noise in an urban setting. Appl. Acoust. 2016, 104, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, A. Lost Sounds: The Story of Coast Fog Signals; Whittles Publishing: Dunbeath, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, A. Village Bells: Sound and Meaning in the 19th-Century French Countryside; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 12913-1: 2014(E); Acoustics—Soundscape. Part 1 Definition and conceptual framework. International Standards Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Schafer, R.M. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World; Destiny Books: Rochester, VT, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, M.; Liu, D.; Kang, J. Sounds and sound preferences in Han Buddhist temples. Build. Environ. 2018, 142, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.P.; Lim, K.M.; Garg, S. A case study of recording soundwalk of Fushimi Inari shrine in Kyoto, Japan using smartphone. Noise Mapp. 2019, 6, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmazer, S.; Acun, V. A grounded theory approach to assess indoor soundscape in historic religious spaces of Anatolian culture: A case study on Hacı Bayram Mosque. Build. Acous. 2018, 25, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynson, M. A Balinese ‘Call to Prayer’: Sounding Religious Nationalism and Local Identity in the Puja Tri Sandhya. Religions 2021, 12, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiser, B.H.; Lubman, D. The soundscape of church bells-sound community or culture clash. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2008, 123, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, D.; Kong, C.; Zhang, M.; Kang, J. Religious Belief-Related Factors Enhance the Impact of Soundscapes in Han Chinese Buddhist Temples on Mental Health. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 774689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R. Conceptualising sound making and sound loss in the urban heritage environment. Int. J. Urb. Sustain. Dev. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R. Classifying sound in the heritage environment. Acoust. Austr. 2021, 50, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R. Contemporary sound practices: Church bells and bell-ringing in New South Wales, Australia. Heritage 2021, 4, 1754–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.L. Sacred sound and sacred substance: Church bells and the auditory culture of Russian villages during the Bolshevik Velikii Perelom. Am. Hist. Rev. 2004, 109, 1475–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.; Fiebig, A. COVID-19 Impacts on Historic Soundscape Perception and Site Usage. Acoustics 2021, 3, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R. For whom the bell tolls: Practitioner’s views on bell ringing practice in contemporary society in New South Wales (Australia). Religions 2020, 11, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killoran, M.; Mc Mahon, C. Unholy row as neighbours complain that noisy churches are... taking the peace. Courier Mail, 16 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Adamski, K. Residents want 100-year-old St Leonard’s Catholic Church bells to stay silent. Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 16 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Naming the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and the Virus That Causes It. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Moloney, K.; Moloney, S. Australian Quarantine Policy: From centralization to coordination with mid-Pandemic COVID-19 shifts. Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 80, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinazzi, M.; Davis, J.T.; Ajelli, M.; Gioannini, C.; Litvinova, M.; Merler, S.; Piontti, A.P.Y.; Mu, K.; Rossi, L.; Sun, K. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science 2020, 368, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. “No Entry into New South Wales”: COVID-19 and the Historic and Contemporary Trajectories of the Effects of Border Closures on an Australian Cross-Border Community. Land 2021, 10, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 Mass Gatherings) Order 2020 (18 March 2020). New South Wales Government Gazette, 2020; 942–946. [Google Scholar]

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 Gatherings) Order 2020 (20 March 2020). New South Wales Government Gazette, 2020; 1035–1045. [Google Scholar]

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 Places of Social Gathering) Order 2020 (23 March 2020). New South Wales Government Gazette, 2020; 1046–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R.; Parker, M. Hitting the ‘Pause’ Button: What does COVID tell us about the future of heritage sounds? Noise Mapp. 2020, 7, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R. Anthropause on audio: The effects of COVID-19 pandemic on church bell ringing in New South Wales (Australia). J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 148, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, C.; Wathey, A. Mapping the soundscape: Church music in English towns, 1450–1550. Early Music. Hist. 2000, 19, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Kang, J. The sound environment and soundscape preservation in historic city centres—The case study of Lhasa. Environ. Plan. B 2015, 42, 652–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P. Turning a Deaf Ear: Acoustic Value in the Assessment of Heritage Landscapes. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelmi, P. Protecting contemporary cultural soundscapes as intangible cultural heritage: Sounds of Istanbul. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 22, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australia ICOMOS. Understanding and Assessing Cultural Significance [Practice Note]; Australia ICOMOS Inc. International Council of Monuments and Sites: Burwood, VIC, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Australia ICOMOS. The Burra Charter. The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance 2013; Australia ICOMOS Inc. International Council of Monuments and Sites: Burwood, VIC, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of the Interior. The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation and Guidelines for Rehabilitating Historic Buildings (36 CFR 67); Technical Preservation Services, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites, Venice, 1964; International Council on Monuments and Sites: Venice, Italy, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Government. An Act to Conserve the Environmental Heritage of the State; Act 136 of 1977; NSW Government: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1977.

- NSW Office of Environment and Heritage. NSW Heritage Nominations Plan; NSW Heritage Office: Sydney, Australia, 2011.

- NSW Heritage Office. Investigating Heritage Significance; NSW Heritage Office: Sydney, Australia, 2004.

- NSW Heritage Office. Local Government Heritage Guidelines; NSW Heritage Office: Sydney, Australia, 2002.

- NSW Heritage Office. Assessing Heritage Significance; NSW Heritage Office: Sydney, Australia, 2001; Volume 2.

- NSW Heritage Office. Assessing Historical Association; NSW Heritage Office: Sydney, Australia, 2000.

- NSW Heritage Office. Historical Research for Heritage; NSW Heritage Office: Sydney, Australia, 2001.

- NSW Heritage Office. NSW Heritage Nomination Plan; NSW Heritage Office: Sydney, Australia, 2011.

- NSW Heritage Office. Community-Based Heritage Studies; NSW Heritage Office: Sydney, Australia, 2013.

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Shifting Baseline Syndrome and Generational Amnesia in Heritage Studies. Heritage 2022, 5. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. An Integrated Architecture for successful Heritage Site Management Planning. CRM J. Herit. Steward. 2007, 4, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Heritage Office. Standard Exemptions for Works Requiring Heritage Council Approval; NSW Heritage Office: Sydney, Australia, 1999.

- NSW Heritage Office. Statements of Heritage Impact; NSW Heritage Office: Sydney, Australia, 2017.

- Heritage Council of NSW. Altering Heritage Assets; NSW Government: Parramatta, Australia, 1996.

- NSW Government. An Act to Institute a System of Environmental Planning and Assessment for the State of New South Wales; Act 203 of 1979; NSW Government: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1979.

- Paul, P.J., II. Codex Iuris Canonici; Vatican: Rome, Italy, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, P., IV. Breviarium Romanum Ex Decreto Sacrosancti Concilii Tridentini Restitutum Summorum Pontificum Cura Recognitum; Vatican: Rome, Italy, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, P., IV. Missale Romanum Ex Decreto Sacrosancti Oecumenici Concilii Vaticani II Instauratum; Vatican: Rome, Italy, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Government. An Act to Repeal the Act 30 Victoria, Intituled An Act to Enable the Members of the United Church of England and Ireland in New South Wales to Manage the Property of the Said Church; to Authorise the Substitution of the Name Church of England for the Name Hitherto Used of United Church of England and Ireland; to Give Legal Force and Effect to the Constitutions for the Management and Good Government of the Church of England within the State of New South Wales Contained in the Schedule to this Bill; and for Other Purposes Connected with or Incidental to the above Objects; NSW Government: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1902.

- Diocese of Sydney. Parish Administration Ordinance; Synod of the Diocese of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Church of England. The Book of Common Prayer, and Administration of the Sacraments, and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, According to the Use of the Church of England; Mark Baskett: Oxford, UK, 1762. [Google Scholar]

- Presbyterian Church of Australia. Worship. The Book of Common Order of the Presbyterian Church of Australia; Presbyterian Church of Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Uniting Church of Australia. The Uniting Church in Australia. Synod of NSW and the ACT including The Northern Synod; Uniting Church of Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, P. A Short Guide for Daily Prayer; Uniting Church of Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A. Directions for the Archdiocese of Sydney from 18 March 2020 until further notice. Sydney, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A. Pastoral Letter to the Clergy and Faithful of the Archdiocese of Sydney regarding the latest restrictions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic 23 March 2020. Sydney, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Patty, A. Bishops lead prayers on church steps as visitors keep social distance. Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 Restrictions on Gathering and Movement) Order 2020 (30 March 2020). New South Wales Government Gazette, 2020; 1149–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A. Third Pastoral Letter to the Clergy and Faithful of the Archdiocese of Sydney regarding the latest restrictions in response to the COVID19 pandemic 30 March 2020. Sydney, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Staff Writer. Church bells to ring, uniting prayers. Catholic Weekly, 27 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A. Sixth Pastoral Letter to the Clergy and Faithful of the Archdiocese of Sydney with Special Directives for Churches and Liturgies following the further relaxation of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, 29 May 2020 in the Light of Pentecost. Sydney, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A. Seventh Pastoral Letter to the Clergy and Faithful of the Archdiocese of Sydney with Special Directives for Churches and Liturgies following the further relaxation of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2 July 2020. Sydney, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A. Fifth Pastoral Letter to the Clergy of the Archdiocese of Sydney with Special Directives for Churches and Liturgies under Step One of the relaxation of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, 13 May 2020. Sydney, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 Restrictions on Gathering and Movement) Order (No. 4) 2020 (30 June 2020). New South Wales Government Gazette, 2020; 3265–3280. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Health. COVID-19 Safety Plan effective 24 July 2020. Places of Worship, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, J. Bells again. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, J. Do you still ring your church bells in the time of COVID19? 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R. The use of recorded bells during COVID-19. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod-Miller, P. Who decides. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fabry, J. Research questions. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, B. Churches ring bells in support of frontline COVID workers and the community. Mudgee Guardian, 22 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, S. All Saints Anglican Church Moree to ring church bells for daily prayer time during coronavirus crisis. Moree Champion, 26 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D. Did you still ring your church bells in the time of the COVID19 lockdown? 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 Mandatory Face Coverings) Order 2021. New South Wales Government Gazette, 2021; 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies, J. Do you still ring your church bells in the time of COVID19? [follow up]. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Macmurray, K. Do you still ring your church bells in the time of COVID19? 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bovis, J. Did you still ring your church bells in the time of the COVID19 lockdown? 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R. Do you still ring your church bells in the time of COVID19? 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R. The bell. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, G.B. The Liberty Bell; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Daum, A.W.; Liebau, V. Die Freiheitsglocke in Berlin—The Freedom Bell in Berlin; Jaron: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).