2. The Early Days

The unique relationship between the

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, the RMO, began more than 200 years ago. The museum was founded in 1818, within the flow of a growing interest in Egyptian culture in the aftermath of Napoleon’s campaign to Egypt, and at a time when the Netherlands had just become a kingdom. The French military campaign had failed, but as a result of the growing knowledge and prestigious art trade at the time, ancient Egypt was

en vogue and the young Dutch nation that was raised out of the Napoleonic ruins used the future museum to distinguish itself in cultural politics. King Willem I invested in the new museum in order to buy prestigious collections on the art market, among which include many high-quality objects from Saqqara that had arrived in Leiden. The most important acquisitions for the Egyptian collection in the early days were the art collections of Jean Baptiste de Lescluze (1926), Maria Cimba (1927) and Giovanni d’Anastasi (1928), which still make up around a fifth of the Egyptian collection today

3. For Saqqara, the d’Anastasi collection is particularly important. Giovanni d’Anastasi was the Swedish-Norwegian consul-general in Egypt and his agents collected many objects from the desert plateau west of the ancient Egyptian city of Memphis, an area ‘rediscovered’ by art dealers in the mid-19th century. In digging the ancient burial grounds, they found the tomb of Maya and Merit, a highly elite couple living in the time of kings Tutankhamun and Horemheb. Their larger-than-life sized statues that arrived in Leiden as part of the d’Anastasi collection are still famous for their outstanding size and artistic quality

4 (

Figure 1).

Maya was overseer of the royal treasury and as such was in service of the reigning king. Non-royal Egyptians did not usually have larger-than-life sized statues, so the statues underline their exceptional status at a time of the young and perhaps relatively weak king Tutankhamun, who perhaps heavily depended on his elderly advisors. The double statue of the deceased couple, as well as the even larger single statues of Maya and Merit, respectively, arrived at the museum in 1929. Fourteen years later, in 1843, the German Egyptologist Carl Richard Lepsius published the results of his Prussian Expedition to Egypt, among which included a map of the tomb of Maya and Merit, its location on a map and a few relief blocks that had entered the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, albeit—as far as we know—without making the connection with the Leiden statues. Obviously, in the middle of the 19th century, access to museum collections worldwide was way more difficult than it is today, and so the link between the tomb and the statues was left to Geoffrey Martin, a specialist of New Kingdom art, who—about 130 years later, in the 1970s—made the connection and managed to convince the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) in London to endeavour and find the tomb of Maya and Merit at Saqqara, indeed in cooperation with the RMO.

The joint Anglo-Dutch excavations were thus initially focused on the New Kingdom (approx. 1390-1213 BCE), aiming at the reconstruction of the archaeological context of parts of the Leiden collection from Saqqara and others that were lost due to the wide geographic distribution by means of the early treasure hunts and the art trade. The first discovery by the then Anglo-Dutch mission in 1975 was, however, not the tomb of Maya and Merit (which would have to wait until 1986), but of an even more important official: general Horemheb (

Figure 2)! Horemheb was even more important, historically speaking, as he was the general who would become king of Egypt, an example of exceptional social mobility. Horemheb’s royal tomb is situated at the Valley of the Kings, near the modern town of Luxor, in Southern Egypt.

Horemheb had thus built the Saqqara tomb for himself, and when he became king, many of his representations in that tomb were adorned with the ureaus, a symbol of royal power (

Figure 3). This suggests that his Saqqara tomb was used for the veneration of Horemheb as king after his ascension to the throne, an idea also supported by of the votive ostraca and graffiti found in his tomb. That same Horemheb is now also linked to Leiden through its more recent partner, the Museo Egizio in Turin, which holds some exceptional statues of Horemheb as king, one showing the king with the god Amun (

Figure 4), the other with his wife Mutnodjmet (

Figure 5), who was probably buried in his Saqqara tomb.

The statue of the royal couple is especially interesting; on the back is an inscription on which Horemheb presents himself as restorer of order in Egypt, as Tutankhamun had done on his famous restoration stela after the Amarna period, with both kings providing important historical documents, even though the text should be viewed as a royal common place of the ruler restoring the order in Egypt rather than an attempt of acuate history writing. The reorganisation of the country by Horemheb is described in the important inscription on the back of the statue now in the Museo Egizio, which informs us about Horemheb having ‘brought order to the country…He has searched all the temples of the gods reduced to ruin in this country and restored them as they were in ancient times. He has arranged for regular daily offerings to be made with all the vessels of their temples made of gold and silver. He has equipped them with priests and lectors selected from the pick of the army, and assigned hem fields and cattle, with all the wherewithal provided.’ On the left-hand side of the throne, there is a variation of the sema-tawy with an imperial slant, where the papyrus and the lotus become the chains that imprison ethnically marked enemy people, and in particular, an unprecedented image of a winged female sphinx, believed to be the personification of Syria, who worships the name of the queen. These reliefs reveal another aspect of Egyptian art: the ability of artists to innovate, vary and enrich the traditional repertoire to meet new communicative needs at the time of Horemheb.

3. Inspiration from Past and Present

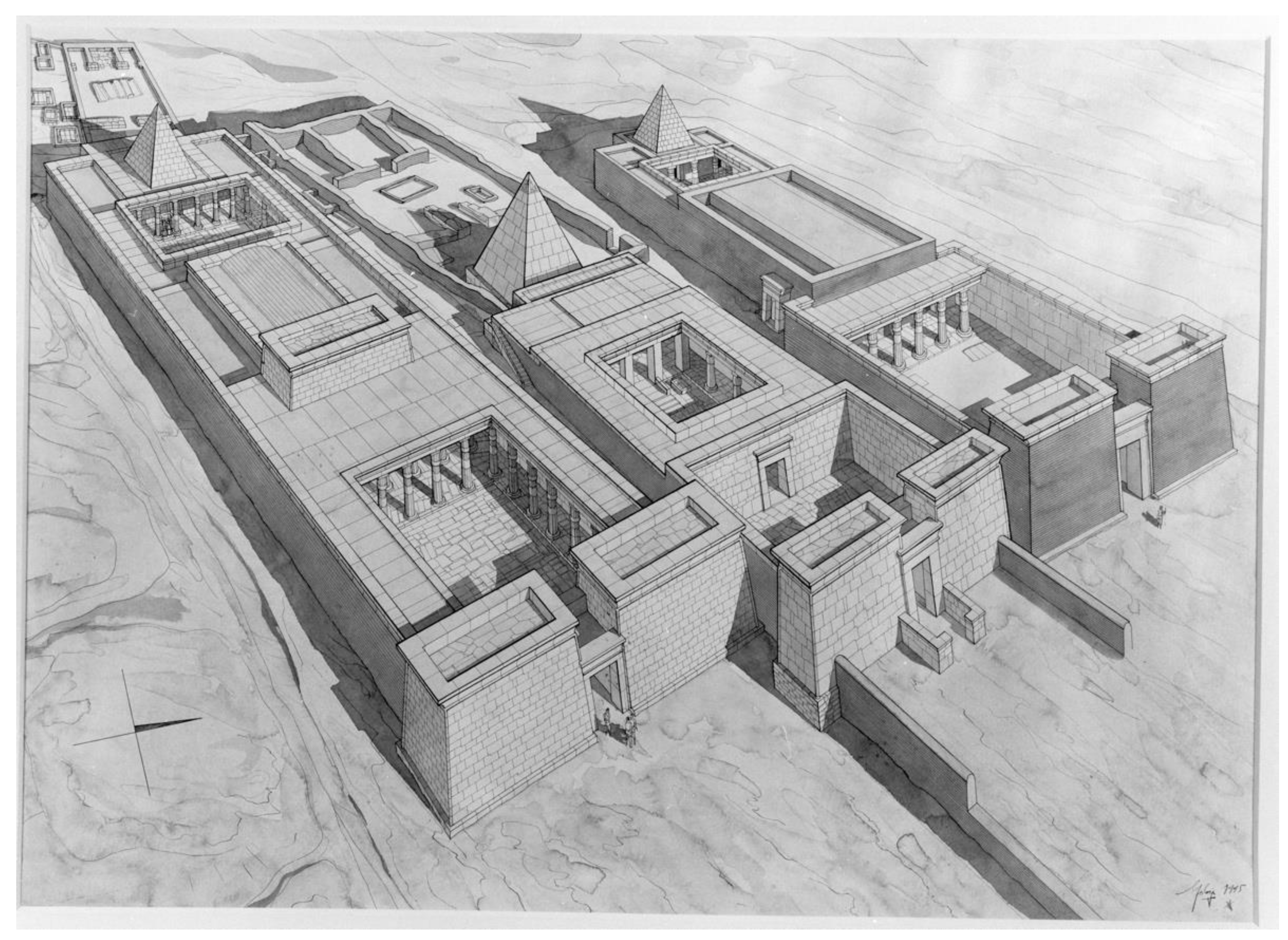

Returning to the Leiden-Turin excavations at Saqqara, the tomb of Maya and Merit was discovered in 1986 (then in cooperation with the Egypt Exploration Society), allowing us to know exactly the place where the three statues stood in their tomb, and thus restoring at least part of the archaeological record scattered by the 19th century treasure hunters. In the past almost 50 years, more than twelve monumental New Kingdom tombs have been found (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), allowing the Leiden-Turin Expedition to target larger questions and move forward to a wider understanding of the site of Saqqara as a whole.

Furthermore, excavation methods have changed since the 1970s and so the new cooperation project no longer focuses on investigating the monumental tombs from the New Kingdom (the time of Maya), but also tries to better understand the archaeological remains of human interaction with respect to the long history of the site. This is vital because at the time of Maya and Horemheb, several Old Kingdom pyramids and numerous mastabas were still visible and had stood there for over a thousand years. For example, if we look at the colourful design of fish and plants in the tomb of Iniuia (

Figure 8), we wonder if he and his artists might have been inspired by the relatively nearby Old Kingdom mastaba of Hesi (

Figure 9). Iniuia worked as scribe of the royal treasury at the time of Tutankhamun like Maya and must thus have worked under Maya’s supervision. Later, he became overseer of the cattle of Amun and high steward. Similar to Maya’s tomb, Iniuia’s was also first dismantled by art traders and his sarcophagus is in the Louvre today (

Figure 10). Curiously, his sarcophagus is not mummiform, as was usual, but wears the clothes of the living, hinting at the desire of the deceased to be revived and live forever.

Quite recently, the expedition received additional financial support by the Dutch Research Council to study Saqqara not only as a burial place for the deceased but also as a dwelling place of the living, i.e., as a place that was regularly visited by tomb builders, scribes and artists who decorated the tombs, the priests who performed ritual sacrifices, and spectators and participants in the divine processions, as well as other passers-by, who strolled over the necropolis, venerated the deceased or became inspired by the ancient monuments

5. All these people used the necropolis in their own way and created a sound space that we can only imagine today

6. Perhaps we get a glimpse of the noises of the ancients when our own excavation works take place at Saqqara, usually including the sound of cheering calls of our Egyptian workmen, the construction works of carpenters and builders, the sounds of the donkeys who carry water to the desert and lorries removing our discarded sands (which obviously the ancients did not have). While we do not intend to equalise modern and ancient Egypt, the logistics are comparable: manpower and anything else needed for both people and their work needs to travel to the desert plateau, the main difference obviously being that we excavate existing structures whereas the ancients had to bring all building materials for their construction works from the city of Memphis and its quarries. In our 2019 season, we found an element that has been interpreted as part of the nod of a chariot

7 (

Figure 11), which may give rise to the idea of a high official losing it when he came to the site to inspect the works at his tomb (an idea not to be proven of course). The procedures of who was granted permission of a plot of land for tomb building by whom, and how exactly the architectural design and the decorative programme were chosen in interaction between tomb owner and his work force remain highly unclear

8. What we see today is the interaction of the ancients with the existing landscape and vice versa, i.e., their own agency and response what was already there that created the cultural geography we excavate today. The owners of the monumental tombs wanted to prosper in the hereafter. They belonged to the highest social echelons of their time and used their burial monuments to demonstrate and immortalise their good taste and high status, but as we shall see they extended their commemoration to a range of others belonging to their household or professional community. Within what was accepted as tomb decoration in terms of layout and design, none of the tombs are therefore exactly the same. Architecture, tomb decoration and texts in the tombs were consciously executed to coordinate and harmonise with neighbouring tombs, or sometimes to outdo them, and while both profession and decency usually play a role in the tombs, people made very different choices as to emphasize either the one or the other, and clear strategies are visible of how the tomb owners chose to knit themselves and others into the commemorative web of the tomb, or make people vanish. The representation of the tomb owner’s subordinates (and sometimes their burial along with the owner) in the tombs thus clearly reflected their social networks, but it also allowed loyal servants to join the ranks of the honoured dead and to benefit from the worship of their superiors. It is therefore necessary to adopt a wider understanding of representations of individuals in tombs beyond the idea that individuals only serve the benefit of the deceased. For example, the offering bearers in the tomb of Maya (

Figure 12) are identifiable by name and title and thereby gain status as being part of Maya’s extended network that is commemorated in his tomb beside other ‘generic’ characters who symbolize a function (such as offering bearer, but not a specific person). How important the choice in favour of or against names and titles was, is clear from the fact that others, for example, the name of one of the servants in the tomb of Tia and Tia (

Figure 13), was deliberately removed, perhaps when he had fallen into disgrace. Another example are the representations of mourners, that typically appear as part of the funerary processions, which are usually represented on northern walls of the entrance areas of the tombs. While the motif of ritually re-enacting the funeral of the deceased is thus quite common, different choices can be detected as to who is part of that procession. Some individuals, such as Meryneith at Saqqara (

Figure 14), seem to stress rather an abundance of mourners. His idea seems to have been to show a large number of people mourning him, without mentioning any names or titles, which would have made any individual in the extensive queues of mourners recognizable to the tomb visitors. Others such as Merymery in Leiden (

Figure 15a,b), whose tomb was probably also situated at Saqqara but has not yet been rediscovered, decided to show a smaller queue, and outlined specific individuals by name and title, among which was his own wife, Meritptah, among other members of his household. These were examples of variation in who is represented, but also the meaning of motifs in the tomb decoration could be creatively played with. For example, the Leiden tomb owner, Paatenemheb, listens to a harp player (

Figure 16), whereas chief singer Raia represents himself playing the harp perhaps as a hint to his profession

9. (

Figure 17).

The Leiden-Turin research also includes carefully compared new finds of wall decoration with relief blocks that have been in museum collections for some time. Recent research by Nico Staring has shown that a relief that is now in Berlin (

Figure 18) originally came from a tomb in the Leiden-Turin excavation area

10. This tomb was rediscovered a few years ago, but its owner could not be identified, because most wall reliefs had already been removed in the 19th century, similar to the case of the Leiden examples mentioned above. As a result of Staring’s work, the tomb owners can now be identified as the military officer Ry and his wife Maia, also living under the reign of Tutankhamun and Horemheb. The relief shows the deceased couple receiving offerings consisting of incense, a libation, papyrus, flower bouquets, a duck and a calf. The bald man wearing a leopard skin is a priest. The accompanying inscription states that he is a servant called Ahanefer, again an example of superiors (Ry and Maia) sharing the commemorative area of the tomb with their loyal subordinate, and is even more intimate than in the case of Maya above. However, the scene is interesting for another reason as well; Huw Twiston Davies’s recent study of the accompanying text has shown the full consequences of the text being an adaptation of the Book of the dead spell 149L, usually describing the underworld mounds

11. By creative rewording, Maia and Ry appropriated the spell to emphasise their desire to stay alive in order to engage into eternal offerings, i.e., a similar message with a different choice of means similar to the one Iniuia seems to have aimed for in his sarcophagus design. Lastly, there is the matter of architectural design. In principle, and probably to some degree depending on people’s means and the space available, there was a choice between either bigger or smaller free-standing tombs, such as the examples discussed above, or rock-cut tombs, such as those in the area of the Bubasteion at Saqqara, not discussed here

12. Slightly younger than the tombs already mentioned, and of Ramesside age, is a small chapel built in the area north of the tomb of Maya, suggesting that the monumental tombs of the time of Tutankhamun and Horemheb were built about 25m apart, with the space in between filled up later, often but not always (see the case of Tia above,

Figure 7) by smaller tombs. In the 2017 fieldwork campaign of the Leiden-Turin Expedition to Saqqara, two small limestone funerary chapels with associated tomb shafts had already been identified. The tomb of Maya in the south would have probably had had a northern neighbour of comparable size. The small limestone chapel in question now was uncovered in 2018, apparently left unnoticed by 19th century art hunters (

Figure 19a). The decoration is unusual: two couples are cut of the limestone in half-relief on the western wall (

Figure 19b). The chapel decoration is architecturally rather uncommon, presenting extraordinarily carved half-cut statues at the centre of the western wall. Six figures are carved here in a very high relief (almost as in the round statuettes) executed with an eye to great detail, even though the state of preservation is not perfect, unfortunately. Two couples stand side by side, the men in the middle, the women on the left and right, each with a child beside her, possibly stressing once again the importance of the tomb owners’ family (albeit we do not know the name and the individuals might as well have been connected by profession rather than family ties). The sleeves of the ladies’ dresses nicely fill the spaces between each couple, hanging in a half-round shape that was fashionable in the reign of Amenhotep III and seems to have celebrated a comeback in the Ramesside period, perhaps as a reference to a glorious past from about a century earlier. The man on the left wears a duplex wig and the typical Ramesside dress, a composite garment consisting of a long bag tunic with wide sleeves in combination with a wraparound sash kilt tied on the front; the man on the right has a bare shaven head and wears a long wraparound sash kilt tied on the front. The kilts of both men display a trapezoid front panel. The face of the male figure on the right is damaged, but his shaven head suggests that he was a priest, while the other man wears the garment befitting a high official more generally. The position of these figures at floor level is also interesting. No parallels are known to us for such chapel decoration in its original architectural context, but there are parallels in museum collections also from the reign of Amenhotep III, such as the stela that shows Nebnetjeru together with his wife and mother (

Figure 20), and the upper part of another one made for the two brothers Ptahmose and Meryptah (

Figure 21), their parents and a colleague, representing again two choices of display for either more emphasis on (blood) family ties and professional representation.

One of the best parallels for the Leiden-Turin chapel at Saqqara is perhaps a stela now in the Louvre Museum (

Figure 22) from Abydos, which shows two standing couples underneath a row of sitting gods. The individuals here represented are the high priest of Osiris, Wennefer, with his wife Ty on the left, and his father Mery with his wife (and mother of Wennefer) standing underneath the seated figures of four gods: Hathor, Horus, Osiris and Isis. A set of four cartouches on the top frame securely dates the stela to the reign of Ramses II., perhaps suggesting a similar date for our Leiden-Turin chapel, and indeed showing that the borrowing from what seems to be an Amenhotep III style was not uncommon.