1. Introduction: Crossroads of Trade and Material Culture in the Pre-Sahara Region

There is a Moroccan proverb that blurs the conceptual opposition between the centripetal forces of human settlement and political organization and their centrifugal counterparts; or, between a centralized regime in the form of city-state, and nomadism, mobility, and openness to the unknown. The Moroccan proverb states “the king’s throne is his saddle”, while there is another proverb that says that “the royal tents are never stored”—indicating that in order to rule, the king has to be in constant motion [

1]. Traditionally, Moroccan kings held four imperial capitals—Fez, Marrakech, Meknes, and Rabat—and they used to occasionally move between them to make themselves known and to exercise their sovereignty (a habit that ceased when the country became a French protectorate in 1912). According to written evidence from one such journey, the encampment of the monarch Mulay Hasan in the Tafilalt (southeastern Morocco) in 1893 consisted of about 40,000 people and close to sixty tents [

1]. The situation of the royal court being in constant transition between the northern centers of official power and the pre-Sahara frontier by crossing the high Atlas Mountains is interesting as a conceptual hybrid between the homogeneity and heterogeneity of human settlement. However, the hybridity of this transitional situation is only conceptual, because in practice, some Moroccan (Arab) kings were reported to have ended their lives at the end of this dangerous journey on account of environmental conditions and local (Berber) political unrest, whereas some other kings were reported to look much older upon their return back to the “Makhzen” (Moroccan center of power and accompanying institutions) in comparison with their appearance just before the journey. This means that in spite of the traditional mobility of Morocco’s monarchical regimes, their governance was far from exemplifying a perfect system of control over all in their subject territory. In addition, the hybrid nature of this transitional situation is only conceptual because, in practice, frontier cities in southern Morocco, such as the historic city-state of Sijilmassa in the Tafilalt, operated as a main regional highway where “its dromedary caravans were as important to the trade of the Sahara as contemporary Venice and its shipping were to that of the Mediterranean” [

2] (pp. 259–261). The case of Sijilmassa is particularly challenging because, on the symbolic and imaginary level, it operated simultaneously as a centripetal-cum-centrifugal settlement. This twofold existence of Sijilmassa was well summarized by the geographer of Islam Eric Ross in his review of a recent pioneering monograph on the city [

3] in the words: “Capital of no powerful empire, its success cannot easily be explained” [

2] (p. 261).

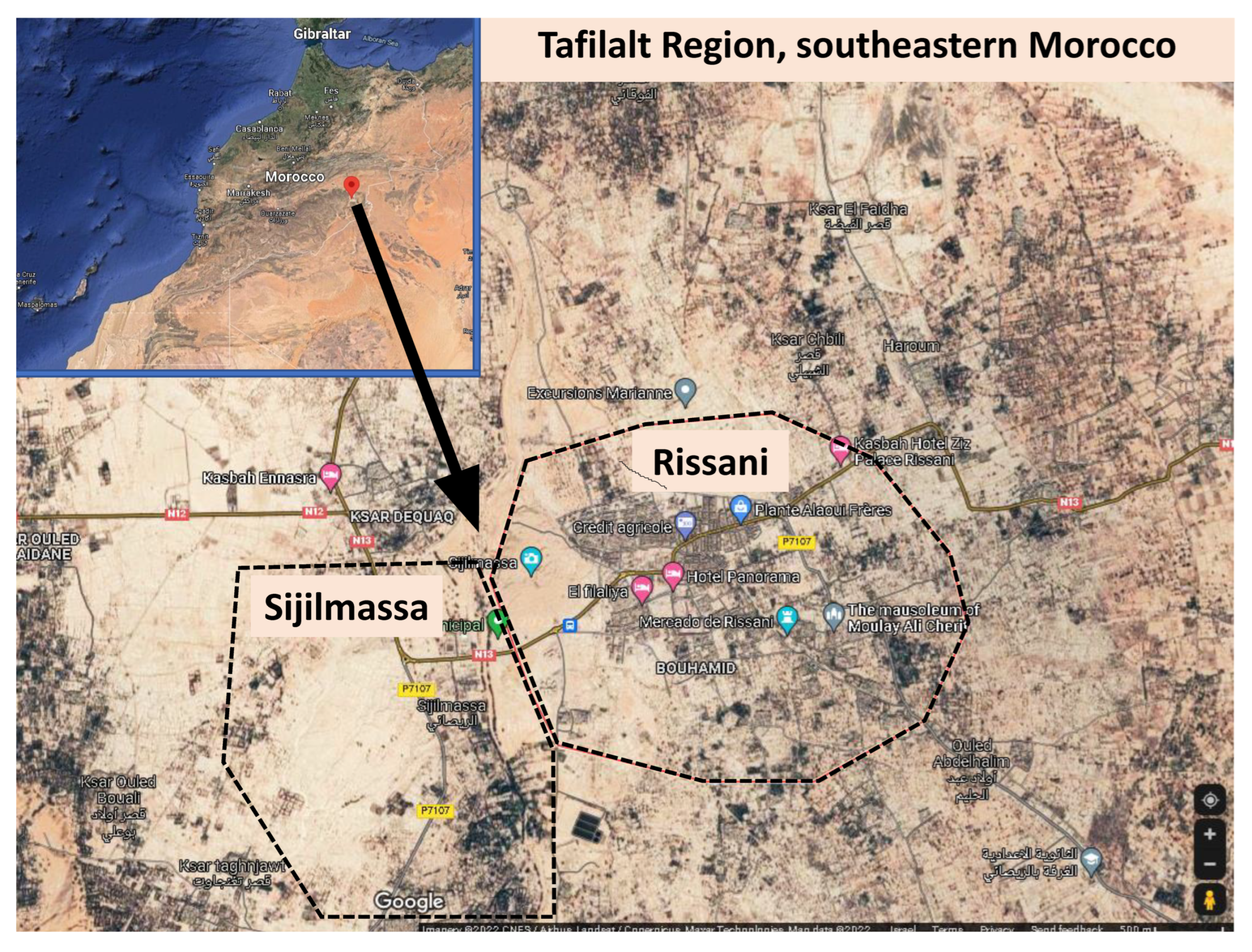

This article analyzes aspects of material culture in the Tafilalt region by intertwining Sijilmassa’s history and the history of its present-day successor, the city of Rissani (

Figure 1). Situations of human mobility, intra-group relations and wide regional influences as engendered by trans-Saharan trading activity are highlighted throughout. Against this background, the history of Tafilalt’s Jewish indigenous minority and everyday existence will be brought into the fore, with particular attention paid to their wedding contracts (

ketubah-s) as an artistic object. Situated between the written text and the material culture, the aesthetic and formalistic symbolism of these contracts will be decoded in an innovative manner, with affinity to both Tafilalt’s built-form and the conceptual visual imagery of the pre-Sahara region, facing sub-Saharan Africa.

The article is quite unconventional in terms of its contribution to the current state of study, in three ways. First, the geographers, historians and archeologists that have seriously dealt with Sijilmassa/Rissani and their environs were far from giving full, in-depth attention to the indigenous Jewish element and its multifaceted material expressions [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Moreover, a monograph on Tafilalt’s Jewish community with respect to material culture, such as the layout of the settlement and its architecture, domestic furniture and cloth, jewelry, and relevant documents has yet to be written.

Second, research on Moroccan Jewry tends to prefer the coastal urban settlements and the areas north of the Atlas Mountains more generally. The few studies on Tafilalt’s Jewry are mainly centered on history and intra-group relations [

13,

14,

15,

16]; their vernacular customs and everyday practices as related to beliefs, ways of life, and rituals in the life cycle [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], and linguistic aspects, lamentations and poems [

23,

24]. Attention to Judaica artifacts or built forms in the Tafilalt is minimal in such publications, which are preoccupied with texts and, to a lesser extent, with popular oral culture. These studies have been not exclusively—but are mostly—conducted by scholars of Judaism—many of whom are of Jewish Moroccan descent, and of Filali (from the Tafilalt) descent. They normally lack an appropriate background in art or architectural history.

Thirdly, area studies scholars that deal with sub-Saharan Africa, West Africa and the Sudanese belt in terms of human geography, architectural history and art history do not normally cover Jewish aspects, nor have an appropriate background in Jewish Studies (these works are too numerous to mention), though rare exceptions exist [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. In its focus on the

ketubah-s, an understudied group of objects, and in transcending the typical geographic boundaries that define scholarship on Morocco, the article’s contribution to scholarship lies also in positioning Jewish material culture within recent studies that are engaged with medieval trans-Saharan trade systems. A recent transdisciplinary work on this subject, for instance, edited and introduced by Kathleen Berzock [

33], puts the Jewish contribution for the making of the trans-Saharan trade infrastructure in the far background, at best

1.

This article is structured around three main sections. The first section reviews the history of Sijilmassa as a settlement through the lens of the “mobility” issue, as a consequence of its involvement in trans-Saharan trade. The section moves between the shifting ruling dynasties, the removal of the regional capital from Sijilmassa to Rissani after the fall of the first (and its short later revival), and the changing form of settlement from a centrifugal (double) walled urban entity into a sporadic, decentralized, quasi-village-like urban form. In the second section, the persistent mobility (an oxymoron) of the Jewish presence in Morocco and in the Tafilalt is expanded upon, in respect of its origins, ethnic composure, geography and organization. Site-related and toponymic aspects of continuity and change are also highlighted in the Tafilalt. Understanding these issues of cultural geography, spatial mobility, architecture and identity is crucial in setting the stage for decoding the decorative and other motifs that appear on the Jewish

ketubah-s, which are the subject of the third, and last, section. The third section is thus focused on traditional Jewish marriage contracts from the region, and their common textual and visual features, in comparison to equivalent documents from other countries and regions. Through the interpretation of the visual repertoire that appears in these contracts, with attention to some key symbols and their meaning, an aesthetic and conceptual conversation with Filali architectural forms will be revealed, as well as with sub-Saharan Africa imageries. This conversation can teach us about the unexpected nature of the dissemination of ideas and cultural “flows” through a long-distance trade network, and about the infrastructures, peoples, and goods that were involved in this trade. This is true even though exact channels for the dissemination of such “flows” are impossible to detect in a teleological, diffusionist manner, such as from one place to another, chronologically [

34,

35]

2. This section puts in the foreground two main motifs in the decoration of the

ketubah-s, namely, the gate and the quincunx. As we shall see, these motifs are tightly associated with the idea of the simultaneous geographical mobility of the Jewish community through its trading networks on the one hand, and its place connectedness on the other. Inspired by analogous arguments concerning the material culture of other (multilateral) Jewish communities in different geographical areas since the late Middle Ages, such as the Atlantic world [

36,

37,

38], this article is a pioneer in applying such an argument in the trans-Saharan context.

2. Sijilmassa: A Trade Infrastructure between Sedentism and Nomadism

The great medieval oasis city of Sijilmassa was renowned for its intermediary role in the long-distance trade infrastructure connecting Mediterranean port cities with the Sahelian port cities of western Sudan. Recognized by the World Monuments Fund as a protected site in 1996, the ruins of the city are located along the River Ziz in the Tafilalt oasis of southeastern Morocco, a few kilometers north of the town of Rissani (

Figure 1). According to medieval Arabic sources, Sijilmassa was established in 757 CE by Kharijite refugees from the orthodox Islamic mainstream [

39]

3, who sought spiritual relief in the hinterland among Berber groups (Banu Midrar, Miknasa) [

40,

41]

4. However, though obscure, the founding history of the city might precede the eighth century by being attributed to a Roman army officer who led his troops from the coast westwards towards Mauritania, up to the borders of the then town of Messa, from which the toponym Sijilmassa is derived [

40]

5. As a trade entrepot that organized caravans for gold across the Sahara and as a Maghrebian center for gold minting, Sijilmassa had flourished for about 650 years [

42]

6. It extended more than five kilometers along the River Ziz and was encircled by mud-brick walls that encompassed both the city and its surrounding oasis of agricultural fields. Its commercial life was organized around a central intramural market and an extramural market for caravans to arrive and depart [

3,

5]. According to archeological estimations, the population of the city in its zenith, about two hundred years before its fall in the late fourteenth century, stood close to 30,000 residents [

5].

Because of its location in the Moroccan hinterland south of the Atlas Mountains on the verge of the Sahara Desert, and on account of its accumulated wealth, Sijilmassa was able to assert its independence from the central regime, especially under its original dynasty of the Midrarid (757–976) [

9]. However, because of these geo-political and economic reasons, the history of Sijilmassa was marked by several successive invasions, mainly by Berber dynasties (e.g., the Maghrawa, Sanhaja, Masmuda, Banu Marin). Of these, the Almoravid movement of the Sanhaja under the spiritual leader Abdallah ibn Yasin should be highlighted, as Sijilmassa was their first conquest in 1055. Following this conquest, the Almoravids stretched over the western Maghreb and Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain), while imposing, in Levtzion’s words, a “rigorous puritan brand of Islam based upon a strict interpretation and application of Muslim law” [

43] (p. 78). Their successors, who established the Almohad Caliphate, took control of the city in 1146 while implementing an even more strict interpretation of Islam [

44]. Apart from these Berber dynasties, Arab political elites also gained an alternating control in the city up until the fourteenth century. Originating in Morocco’s main urban centers of power, Spain (the Cordoban caliphate) and Tunis (Kairouan), these elites coveted this important northern terminus in the western trans-Sahara trade route (

Figure 2). In the writings of a dozen Muslim visitors between the ninth and the sixteenth centuries (about Sijilmassa), as well as in current Moroccan imagery (about Rissani), the site signifies simultaneously a far-away place and an important crossroads [

3].

Sijilmassa was still a thriving and a relatively safe place during the four-month visit made by the Moroccan traveler Ibn-Battuta on his way to Timbuktu, at the end of 1351. Ibn-Battuta described a city laid out north–south, which included sanitary infrastructure of public toilets and baths, gardens, decorated houses and traded goods from Cordoba to Cairo [

3]. Sijilmassa was finally abandoned in 1393, due to instability caused by rivalries among and within the Berber ruling dynasties, especially the Almohads and the Marinids, and by further invasions of semi-nomadic tribes that gradually immigrated from the Arabian Peninsula. These events coincided with the growing presence and political influence of Spanish and Portuguese agencies along Morocco’s western coast during the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries, what stimulated a new demand for gold through the coastal ports. As a result, the trade network had been diverted westwards from Tafilalt, and the role of Sijilmassa reduced [

46]. Though it is hard to estimate the proportion of gold that the Portuguese had managed to redirect towards their coastal trading settlements, this development clearly negatively influenced the trans-Saharan caravan trade and those who traditionally profited from it—the oasis centers of Tuwât and Drâa-Tafilalt [

47]. Sijilmassa was rebuilt in the early eighteenth century under the orders of Morocco’s Sultan Moulay Ismail (1645–1727) who was born in Tafilalt, but this venture was finally overrun and destroyed by Berber groups (Aït Atta) in 1818 [

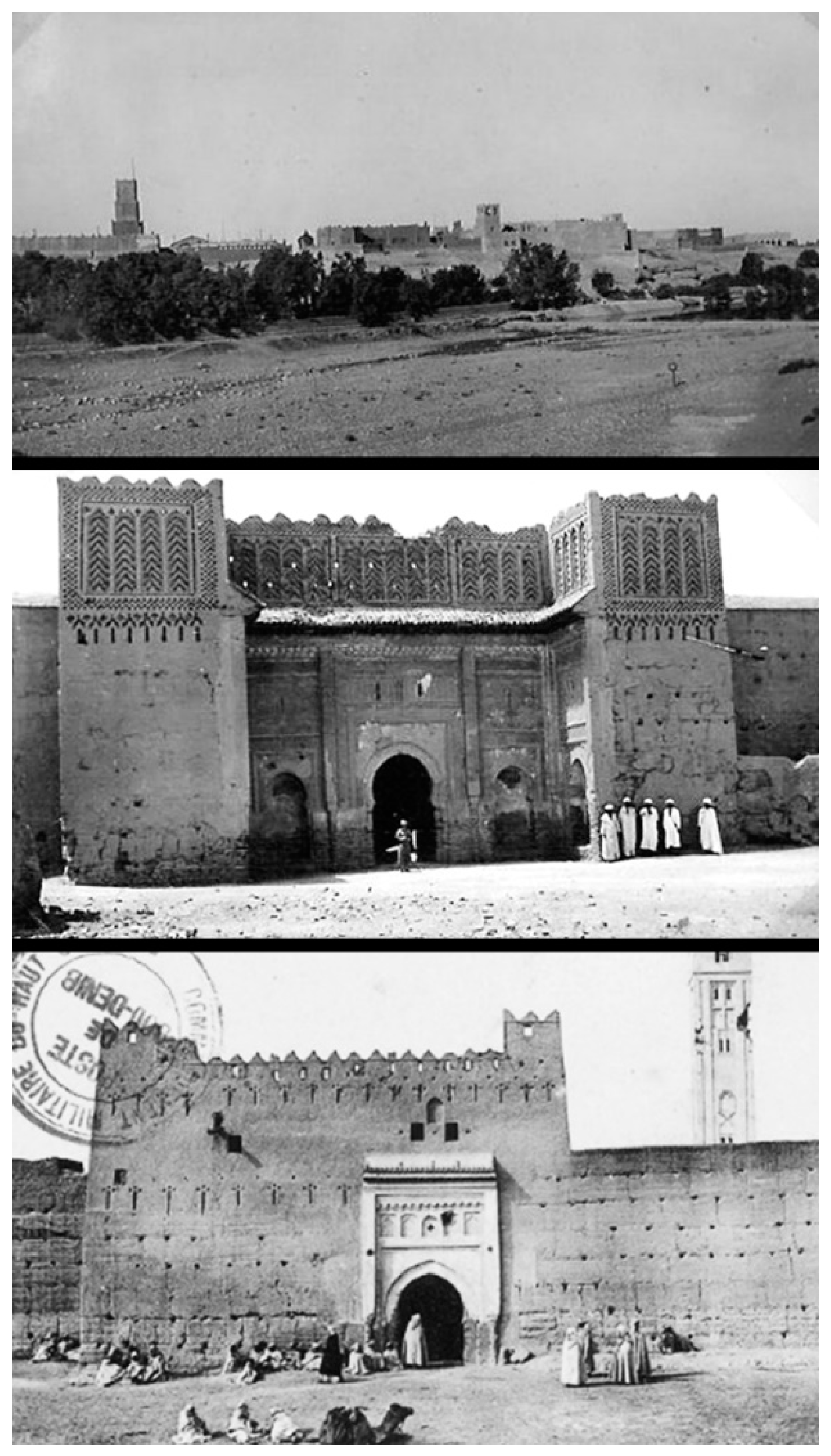

48] (

Figure 3).

In fact, following the fall of Sijilmassa in 1393, the Tafilalt region became decentralized in terms of both political power and its settlement form. Together with the decline in the gold trade, the centripetal morphology of the settlement had turned into a centrifugal one by the seventeenth century. A new landscape of a multiplicity of

qaṣar-s (commonly known as “qasr” or in the plural, “qsour”, meaning mud-brick walled villages) and

kasbah-s (citadels or castles) was created (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), consolidated by an elaborate infrastructure of dams and canals along the Ziz [

7].

According to oral traditions collected among the

qaṣar-s, there are some villages that claim to be the first established in the region after the fall of Sijilmassa, with their residents claiming to be direct descendants from the city [

5]. Gradually, from the fourteenth century onwards, Rissani, the neighboring town of erstwhile-Sijilmassa, became the most dominant city in the region against the background of its dozens of

qaṣar-s. Rissani is inhabited today by close to 25,000 residents that constitute part of the over 80,000 residents in the Tafilalt region (

Figure 6). Aside from grain and vegetable fields, Rissani’s major economic activity is still the production of palm dates which, as in historical times, has contributed to the wealth and power of the local (Alaouite) dynasty. As the current Moroccan reigning dynasty, the Alaouites assign special importance to the Tafilalt region, from which they rose to power at the beginning of the seventeenth century.

Historically, in addition to palm dates and alongside the trade in gold, another source of wealth of the Filali-s (the inhabitants of the Tafilalt) was the fact that the region was a strategic point of passage for the so-called “Salt Road”, along which trade caravans traveled between the northern and southern parts of the Sahara. While this trade infrastructure had consisted mainly of salt, cloth, leather, weapons and spices were additionally exchanged in the south for slaves and gold. By connecting Fez to Timbuktu and Koumbi Saleh (the capital of the ancient Ghana empire) (

Figure 2), Sijilmassa/Rissani and their environs constituted “the farthest point to which water flows seasonally outward from the Atlas […] Beyond the Tafilalt stretches the full Sahara, where the interstices of human life are few and far between” [

5] (p. 82). Cosmopolitan Sijilmassa therefore “linked different ecologies of people and places together: through it, the worlds of Islam, North Africa and the Mediterranean were connected with the Sahara, West Africa, and the non-Muslim world” [

6] (p. 29). The population of Sijilmassa, as a prosperous commercial center based on long-distance connections, was an inherently mobile, “floating population” [

14] (p. 259).

The city’s social tapestry on the eve of its decline in the fourteenth century encapsulated several basic divisions including oasis residents and nomads; Arabs and Berbers with variegated origins; Muslim and Jews; freemen, slaves and servants, mostly originated from Western Sudan; holy men (or saints, both within Islam and Judaism) and ordinary people (as identified by Lightfoot and Miller, “Sijilmassa” [

5]). We will expand on the Jewish indigenous element. Documented in passing in the writings of several Muslim visitors to Sijilmassa until the late medieval period [

14] and continued through Sijilmassa’s modern incarnation, Rissani and its metropolitan

qaṣar-s by the 1960s—the Jewish element was an important agent in the shaping of the trade infrastructure in the Tafilalt. There follows a background on the Jewish presence there and its special character, structured around the issues of mobility and material culture that are central to our argument. This background is essential in order to fully grasp the subsequent innovative analysis that decodes several key forms and formulations in the visual repertoire of the Filali-Judaic material heritage.

3. The Jewish Presence in Morocco and the Tafilalt: Persisting Mobility, Persisting Ancient Toponymy

Scholars of Judaism have pointed to the long-term Jewish presence in North Africa, including Morocco, over the last two millennia. Archeological evidence such as a Hebrew epitaph found in the Roman site Volubilis, and other Judaic objects dated to the third and fourth centuries, testify to this presence from at least the times of both the Roman and the Arab conquerors [

49]. There are many legends regarding the Jewish presence in Morocco before that time, but none of them are verifiable [

50]

7. The Visigoth persecutions in seventh century Spain resulted in further Jewish immigration waves, as did the reconquest of Spain by the Christians at the end of the fifteenth century [

51]. The Jewish communities in Morocco were often thriving, and constituted a considerable minority. Of them, about three quarters lived in urban centers by the late nineteenth century, and a quarter lived in small towns and rural settlements at a considerable distance from the urban centers. Among the latter communities that had been inhibited included numerous villages and small towns in three great valleys of the pre-Sahara region, that is, the Sous, Drâa, and Ziz (Tafilalt) [

52,

53,

54]

8. Specialized in trading in urban-based goods and producing artisanal crafts, Jews of the pre-Sahara region constituted an important and active element in the traditional economy [

52,

55,

56].

From medieval times to the nineteenth century, both the country’s central authorities (the Makhzen) and the often-competing regional authorities south of the Atlas obliged the Jews to live in the

mallāḥ-s, that is, residential quarters that were specifically designated for Jews. Before the establishment of the first

mallāḥ in Fez in 1438 under the Marinid Sultanate, Jews cohabited with Muslims in the same quarters in the urban areas [

57]. Forms of the

mallāḥ could vary between a quarter within a Muslim urban settlement encircled by a wall with a main gate, and a concentration of Jewish residences without a surrounding wall, within a walled

qaṣar/village. In remote

qaṣar-s, it could be just a hamlet separated from the village or an allocated space in a Muslim premise [

52] (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). The latter situation was indeed characteristic of the rural areas, where a few Jewish families or wandering male artisans often shared the same streets or even the same houses with Muslims [

16]. The official explanation for the confinement of the Jewish communities in the walled

mallāḥ-s was for protection by the central authority or its provincial local governors and military. As pointed out by Joseph Chetrit, Judeo-Berber and Judeo-Arab relations were ambivalent despite their intimate acquaintance, mutual knowledge, and mundane cooperation. Jews in Morocco were considered “as the religious, cultural and political Other” [

16] (p. 20), whose socio-political status was legally structured as

dhimmi, that is, inferior subjects and dependent high-tribute payers. Muslims (Arabs and Berbers) were the “dominant masters and Jews were protected clients at best or else people with neither protection nor esteem in ordinary situations” [

16] (p. 20) (see also [

15,

58]). Moreover, not only were the

mallāḥ-s located, especially in many of the

qaṣar-s of Tafilalt, as the first quarters right after the villages’ main gate, but this gate constituted the most vulnerable place during the region’s many rebellions against the central regime and intra-Berber quarrels, particularly until the establishment of the French Protectorate (1912–1956) [

56,

59,

60]

9. Additionally, the

mallāḥ-s’ confinements often facilitated anti-Jewish violence, involving human losses and material damage [

13,

47,

61,

62,

63,

64]

10, while facilitating the spread of infectious diseases, such as bubonic plague [

24] (p. 782). The inherent weakness of Morocco’s Jews and their fragile and insecure status had lasted a very long until their dramatic departure from Morocco, mainly to Israel, in the 1950s [

63,

64,

65]

11.

In the pre-Sahara region, biologists have drawn our attention to the unusual blood group frequencies of the Jews of the Tafilalt oases, particularly to the very high occurrence of blood group B (the collection of specimens for testing occurred between the 1950s and the 1970s in both Morocco and Israel and was used for various studies [

66,

67,

68]). These data, including other genetic frequencies that characterize the Jewish communities of the pre-Sahara region, is marked by a considerable genetic distance from the neighboring Berber populations, as well as from black populations in the north-western part of Africa with whom there were trade and other occupational contacts. Moreover, considerable genetic distance has been found from other Jewish communities, such as of Libya, or even from the Sephardic Jews of Morocco [

68]—that is, the communities that were expelled from Spain in the fifteenth century, and who for hundreds of years after, were regarded as “exiles” by indigenous Jewish “residents” who feared commercial rivalry. The Sephardic, on their part, who tended to live in the coastal cities, also separated themselves from the “native” Jews. This voluntary separation took the forms of preserving their own cultural practices, synagogues, cemetery sections, material culture, etc. [

69]. While biologists assign the high degree of genetic isolation of Tafilalt Jews to their geographic and religious situation (bordering the Sahara to the south, the Atlas Mountains to the north, Algeria’s political boundary to the east, and with 200 km of stone desert to the west until the next river), they characterize the Filali Jews’ blood group as essentially Mediterranean and southwestern Asiatic, as found in many parts of southern Europe or north Africa [

67]. Thus, the Jewish communities from the interior of the country “are more likely descendants of earlier preexisting communities […] if so, then these ‘inland Jews’ are even more distinct from the Arab and Berber populations among whom they lived than are the coastal urban Jews” [

68] (p. 470).

However, this picture of various scales, degrees and spatialities of isolation of (Filali) Jews does not contradict, but rather completes, research conclusions in both osteoarcheology and history regarding the human populations from the pre-Sahara region over the long term (including the indigenous Jewish component). That is, that there has been a great deal of spatial mobility and a dynamic inter-ethnic correspondence in this region, against the background of long-distance trade and related occupational expertise. For instance, archeological evidence shows that populations used to traverse the Sahara Desert in spite of the environmental challenges of heat and rough physical terrain. At the same time, the examination of cranial morphology testifies that the Sahara still posed limitations to gene flow between the regions’ populations [

70,

71]. In the same line, in his chapter “The Jews of Sijilmasa and the Saharan Trade” (from the tenth century to the city’s ruin in the sixteenth century), Nehemia Levtzion highlights aspects of geographic mobility, resilience and fluidity that were shared among the participating groups in this trade [

14]. According to Levtzion, after the Arab conquest of North Africa and during the Middle Ages, the Jewish traders of Sijilmassa and environs did not cross the Sahara themselves

12. Rather, they controlled much of the commodities that were brought from the Sudanese region and its southern hinterland, and the transfer of these commodities from their pre-Sahara posts to the Mediterranean coastal cities.

For instance, a tenth century journey from Sijilmassa to Qayrawān lasted two months, passed through Maghrebian (not Saharan) deserts and involved a cosmopolitan network of Jewish traders and scholastic aristocracy. While Sijilmassa prospered and was renowned as a center of Jewish learning, this network of human capital stretched as far as Fustat (Old Cairo) and further east, with a possible connection to Iraq. In the words of Levtzion “Such long-distance connections and mobility is typical of a floating population associated with prosperous commercial centers” [

14] (p. 259). Identifying three different sections of trading infrastructure along this trans-continental system—each with its own specialized ethnic groups, means of transportation and economy—Levtzion pointed out Sijilmassa and environs as part of the first section. In this section, the northern pre-Sahara region, donkeys were mainly employed. The two other sections are the southern Sahara region of the Sahel (e.g., the towns of Walata, Timbuktu and Gao), using camel caravans and conducted by Arab and Berber traders, and the northern fringe of the forest (e.g., Bonduku, Wangara), where donkeys were interchanged with human porters and where African Muslims met with other forest groups [

14] (p. 256). Though the Jewish traders often had to continue their occupations under harsh conditions of anti-Jewish riots, persecutions and forced conversions (see endnote 10), the best environment for their economic prosperity was that of political decentralization and ethno-religious pluralism [

72].

From a historiographic point of view, the collapse of Sijilmassa in the late fourteenth century was accompanied by a discontinuity of historical sources. In terms of archeology, written sources and oral histories, it is difficult to trace the period between the city’s fall and the renewed flourishing of the Tafilalt region from the seventeenth century (following the introduction of a large-scale infrastructure for irrigation through canals and dams by the Alaouite dynasty and their conquest of this region, and then of Morocco). Since the seventeenth century, the main form of settlement in Tafilalt has been mainly in dispersed villages and/or

qaṣar-s, each with a different morphology and social composition. The architecture of the

qaṣar-s does not normally predate the seventeenth century, and many of the pre-Sahara Berber groups, such as the Amazigh, possess hardly any written primary sources reflecting their historical heritage [

4,

73]. Interestingly, Sijilmassa occupies a special place in the memory and oral history of specific village communities that claim to be descendants of the city, who gradually reinhabited the place after its fall. According to oral interviews that were conducted in Tafilalt in summer 1992 (with over 100 informants from over 20 villages), most Arabic speakers claimed to be descended from the city, and their oral traditions narrate its destruction [

5] (p. 87).

Similarly to other autochthonous populations, we can only presume that at least some of the small, dispersed, and resilient communities of Jewish traders and artisans that resided in the

qaṣar-s’

mallāḥ and other places in the vicinity of the villages of Tafilalt since the seventeenth century (and in nearby areas such Sous, Drâa and eastwards in Tuoat), also originated in Sijilmassa. This is a presumption, as research on the Jewish material heritage and monuments at the pre-Sahara region both before and after the seventeenth century is meagre, including their currently abandoned quarters, and other public or private buildings (now inhabited by their neighbors, in secondary use, or deserted in a dilapidated state) [

52,

56,

73]. Due to the relative scarcity of historical sources south of the Atlas Mountains, the more Eurocentric-bias in the research literature regarding Moroccan Jewry and the Sephardi heritage north of the Atlas, a complementary study on the Judaic unique heritage at the pre-Sahara region has yet to be conducted.

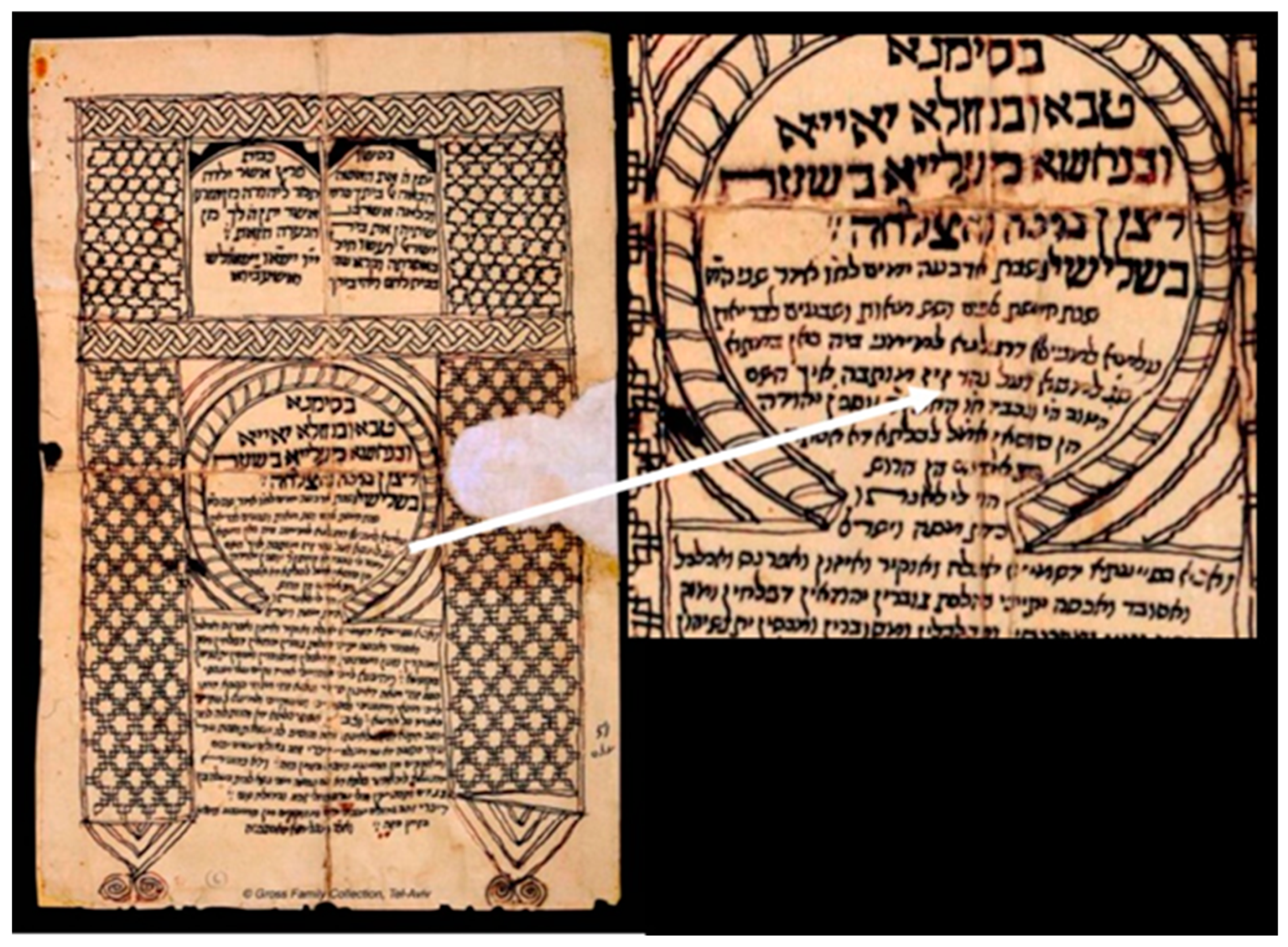

Against this background, we would like to turn our attention to written documentation that strengthens this presumption and the role of Sijilmassa in the historical memory of Tafilalt’s Jewish communities (the area become a flourishing center for Jewish learning from the nineteenth century, under the Abuhatzeira rabbinical family) [

22,

74]. This can be found in the traditional version of contemporary

ketubah-s (Jewish marriage contracts), as prepared by the influential Abuhatzeira family; the earliest of such documents that have been preserved from the southern Tafilalt region are dated to the early nineteenth century, and the latest are assigned to the mid-twentieth century

13 (for more, see next section). While it has been a convention to indicate in the

ketubah the locality where the marriage took place, we have noticed that in almost all the

ketubah-s from that period in Tafilalt, the old toponym of “Sijilmassa” was indicated as the sole (imaginary) archetypical place for the marriage. This is regardless of the specific village/

qaṣar or town the married couple came from. Among the relevant examples for such settlements are: Rissani, Erfoud, Essifa, Jorf, Mezguida, El Gourfa, Irara, Guighlan, and Bouzmella; all of these settlements still exist today and contained a

mallāḥ until the early 1950s. Moreover, all of these settlements surround Rissani (Sijilmassa) more or less concentrically. Their Jewish communities were traditionally referred to in the

ketubah-s in these very words, as to where the wedding ceremony was conducted: “here in the place of Sijilmassa that sits on the River Ziz.”

14 (

Figure 9).

In the writing of the Abuhatzeira family [

75,

76]—particularly, the

responsa literature of the rabbis Maklouf and Shalom, which was compiled during their time in the Tafilalt and nearby Béchar (Algeria)—there is an explanation for this practice; that is, for this specific community to identify itself with a toponym of a city that had long ceased to exist and was no longer used in everyday parlance of the surrounding groups for spatial orientation. The explanation is based on pure halakhic considerations, according to which, in spite of the fact that the toponym of Sijilmassa has been generally forgotten even by its own people, its memory has been preserved in Jewish written documents of marriage and divorce contracts from ancient Sijilmassa, even though such documents have not survived to this day. According to Jewish law, two main conditions must pertain in order to continue using the ancient name and not to introduce any toponymic change: (a) that the original ancient name “has not been forgotten completely”, which means that it was indicated in marriage and divorce contracts that took place in the settlement in historical times; and (b) that the Jewish community that inhabited the settlement in ancient times did not cease to exist because of forced expulsion (forced exile, anti-Jewish violence, etc.), or that the original toponym did not change because of, and following, a forced expulsion of the Jewish community [

75,

76]. If these two conditions exist, as in the case of Sijilmassa, then, by the virtue of genealogy, the old name is legally valid and should be used at the present.

This means, among other things, that Filali Jews used to designate themselves as “Sijilmassi” as well (this is also true regarding today, both in the diaspora and in Israel, as part of their identity and cultural heritage). By recalling the non-existent city—in which they were aware there had been thriving Jewish scholasticism and commercial enterprise—they had managed to create some continuity between the present and the past, establishing in modern Tafilalt similar qualities of religious scholasticism and commercial enterprise (

Figure 10). Even if there is an element of imagination in this toponymic continuity that might have been structured through the textual formula of the

ketubah-s (and divorce contracts), the commemoration of Sijilmassa in this way testifies to its collective symbolic role in the everyday life and rituals of the name-preservers. This commemoration also testifies to the community’s place attachment as an essentially indigenous people, and to the validity of their historical memory. For instance, anti-Jewish riots in the Tuwât, Drâa, and Tafilalt regions, including persecutions of Sijilmassa’s Jews by the city’s ruling dynasties in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, have been memorialized for centuries through tragic poems [

24,

61]. Both Maklouf and Shalom themselves, and many other Abuhatzeira family members, had to flee to various areas within and beyond the Tafilalt following the murder of Rabbi David Abuhatzeira in 1920 (Maklouf to Erfoud and Shalom to Béchar)

15. Yet in spite of and contrary to this backdrop, both tell us with confidence that the Jewish community that inhabited Sijilmassa in ancient times did not vanish because of antisemitism. To borrow the words of Shalom in this context:

After all, we have heard in our ears the elders telling and saying, Jews and Ishmaelites living in the land of Tefilalt, that initially there was one big city and all the people were in it […] and one morning that whole city was destroyed, with all its inhabitants, and all those who were saved from death, Jews and Ishmaelites, supported for their families and built houses, towns and villages, in the same original place of the above-mentioned first city, and settled in them and their sons and grandsons to this day […]. Once I visited one village in the Tafilalt called Mezguida, and there was a gentile there, very old, of about one hundred, who told me that when he was a child his father told him what he heard from the father of his father, that in his days the entire Tafilalt constituted one big city, and then it fell. And we also say that there are still visible and hidden signs from which it is clear that it was so and happened in that way. We proved and ascertained that at first the land of Tefilalt was one city and was called Sijilmassa, and therefore it was written in the divorce and marriage contracts here in the place of Sijilmassa that sits on the River etc. Then he even said that that city was destroyed and all its houses fell etc., and its remaining people returned and rebuilt houses and towns and villages in that destroyed place. Still, they maintain the original practice to write in the divorce and marriage contracts in the place of Sijilmassa without indicating the name of their own villages […] and it is forbidden to change from past years the practice of earlier times [

76] (pp. 371–372, authors’ translation).

This means that the indigenous Jewish consciousness “knew” that Sijilmassa Jewry fell together with the fall of the city, and that it became a centrifugal settlement existing together with the surrounding Berber and Arab communities, and not because of any specific forced expulsion. This oral and partially written local history sits well with the oral histories that were collected from the surrounding groups as to the fall of the city, and as to its later decentralized incarnation, which partly involved descendants of its original inhabitants [

3,

5]. In addition, it can be presumed that the memory of Sijilmassa as a regional centripetal center of power was idealistically stimulated by the Filali Jewish community facing their more recent sporadic, highly mobile demography of settlement: a transitional situation “resulting from drought, epidemics and the shifting of economic activity from one town or region to another […] often related to political changes” [

52] (p. 61), and considering the organization of these communities in the form of “chains of small mellahs (often numbering only several dozen families) were separated by small distances, rarely more than a day’s walk” [

52] (p. 63), as part of the network trade.

4. Jewish Marriage Contracts in a City of Transit: Formalistic Trajectories

Positioned between the written text and the material culture, the Jewish marriage contract is a central object in the wedding ceremony. Apart from the text and its legal implications (providing for a man’s wife to receive an agreed sum of money from him in case of divorce or death), the document acts as a protective artifact, an amulet, in this crucial and symbolic moment in the life cycle [

77]. Throughout history, many communities globally, and especially Sephardi and Oriental Jewry, have turned this document into an artistic object, by incorporating decorative imageries. The visual repertoire of the

ketubah-s has been thus associated with universal Jewish concepts and related motifs of the wedding occasion, such as certain signs, charms or letters of blessing. Among the latter are, for instance: fish for fertility, the Shield of David (hexagram) for protection, gate and bricks for building a new home, drawings of Jerusalem’s landscapes as a place of yearning, and the numbers five and eighteen (

hayy/to live) against the evil eye. At the same time, decorations made under the influence of the wider hosting culture, region or country can be also noticed in the

ketubah-s, such as: zodiac and putti (male child angels) in Italy, crescent and stars in the Ottoman Empire, a gate in the form of a horseshoe arch in North Africa, a tapestry-like arabesque in Persia, or an arabesque dotted with the lotus flower in India [

77,

78]

16 (

Figure 11).

The Filali-Sijilmassi traditional

ketubah-s shared some special features in terms of text and decorative images [

19,

79]

17. These documents, in addition to the above-mentioned indication of the (old) toponym that was identified with the place of the ceremony, tended to be relatively short in comparison with the traditional Sephardi

ketubah. The Sephardi document, for instance, tended to include the signatures of those participating in the ceremony, to mention the names of previous family ancestors, and to incorporate a list of dowry items or additional sums of money. The Filali traditional practice was to attach a separate document for such a list, in order not to embarrass poor couples because the

ketubah is read in public at the ceremony [

19]. As for the images, the Filali-Sijilmassi

ketubah tends to be especially simple, in conformity to the artistic style of other items of material culture, such as jewelry, cloth or furniture (see examples below). These documents normally share a decorative formula of a central gate in the form of a colonnade or arcade, sometimes horseshoe-shaped. The gate represents the publicity of proclaiming the wedding, and the entrance to a new phase in life. Above the gate appears a row of two or three windows, in which blessing verses are incorporated to symbolize hope and protection, sometimes with the addition of figurative motifs from the region’s mundane life such as palm trees, or a charcoal dispenser and a jug of water that represent the drinking of tea and the flow of life. Often, very simple geometric or floral shapes are also intertwined in the design, which is generally controlled by contour lines [

19] (

Figure 9 and

Figure 12).

We would like, however, to contribute to the research literature that has dealt so far with Morocco’s Sephardi [

77,

78] and Sijilmassi [

19]

ketubah-s. This is by further analyzing and interpreting two of the key decorative motifs that characterize the Sijilmassi

ketubah-s, which are the gate and the geometric shapes. In bringing together transdisciplinary research studies, a new light can be thrown on these documents of Judaica: on the one hand, our interpretation points to the “place attachment” of the Jewish communities in southern Tafilalt; on the other, it points to the simultaneous “mobility” of these communities in terms of bridging between the different regions and peoples that were engaged in the long-distance trade infrastructure. By highlighting the expressions of material culture of these communities, our interpretation adds another thread to the tapestry of the broadening field of the African continent’s art history. It also stresses the traditional role of these southern Jewish communities as traders-

cum-scholars-

cum-artisans along the trans-Saharan route [

29,

30], and their active involvement in the production of the region’s cultural heritage.

The idea of (frequently compulsory) Jewish geographical mobility and trading networks since the Middle Ages, on the one hand, and Jewish place connectedness wherever their communities settled, on the other, has already been discussed by Jewish Studies scholars, though not normally regarding the trans-Saharan trading infrastructure. For instance, the history of Jews in cosmopolitan maritime trading centers since the late-medieval to the modern periods has been researched by several scholars with respect to their material culture [

36,

38]. As shown by Barry Steifel [

37], synagogue’s architectural and internal design in the Atlantic world (that is, in the European states that bordered the Atlantic and their colonies or former colonies), following the expulsion of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula in the late fifteenth century, responded to the changing needs of their respective communities. In terms of spatial arrangement and ornamental programs, these sacred spaces operated at two levels simultaneously: they echoed geographical and historical generic motifs (such as the Holy Temple, or Spanish stylistic influences), and they reflected site-relatedness in their building materials, built shapes and iconography. The mirroring of this bipartite tendency in synagogue design in this context of mobility-cum-place attachment can be paralleled with the trans-Saharan trade routes and the prominent role of Sijilmassa and Sijilmassi Jews in this infrastructure on the one hand, and the visual motifs that were included in the Jewish

ketubah-s on the other. In its examination of this group of objects of material culture in Morocco, the article highlights two main visual motifs, which are the gate and the quincunx. As will be shown below, the gate motif can be aligned with the idea of Filali Jewish connectedness to the place of Sijilmassa, while the quincunx can be aligned with the concept of Filali Jewish mobility.

4.1. The Gate: A Motif of Place Attachment

Because the wedding ceremony is traditionally perceived as a critical moment in the series of life cycle stations, “the gate” is one of the prominent and oldest motifs in the

ketubah. This is true especially among Sephardi communities in Europe and beyond, and Jews in Islamic lands at the time, because of their particular attention to the decoration of the document. In many of the

ketubah-s, in a practice that is also present in the décor of the

ketubah-s from the Cairo Genizah

18, the associated blessings are located in the upper part of the document in bolded superscriptions in square letters (

Figure 9,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13). A recurrent such blessing was

yivnu ve-yatsliḥu (“May they build and prosper”) for a strong and safe home, in view of life’s uncertainties, also accompanied by an illustration of a gate and bricks [

77] (p. 111). The Cairo Genizah reveals written evidence that testifies to the faithful connections between North African Jewry (including Kairouan and Sijilmassa, which were also interconnected through a few selected Jewish marriages intended to promote this trade route) and the

Geonim. This latter term refers to a period from the seventh century to the mid-eleventh century CE, when the presidents of the two great Babylonian Talmudic Academies and the one in Eretz Israel (the Land of Israel/Palestine) were accepted as the spiritual leaders of Jewish communities worldwide. Correspondence from the tenth and eleventh centuries between the North Africa communities and the widely consulted Geonim dealt with seemingly every practice and aspect of life, including marriage issues and contracts, with mentions of Sijilmassa [

17,

80].

Therefore, in Morocco, in matters of the artistic style of the

ketubah, we identified two main architypes of “gates”: a simpler and more graphic version of the “residents” (who were the Jewish indigenous communities with pre-fifteenth century roots), among whom is the Filali-Sijilmassi

ketubah (

Figure 9 and

Figure 13), and the more flamboyant version with arabesque-like, curved floral motifs of the “exiles” (the post-fifteenth century Sephardi communities) (

Figure 13). It could be interesting to suggest some association, even if only implied and imagined, between the predominance of the “gate” as depicted in these traditional documents of Judaica as mirrored in

ketubah-s from Morocco, and the predominance of the “gate” in the physical world, namely, in Morocco’s traditional built-form. The gate has been a salient feature in the architecture of the

qaṣar-s, which are rural walled villages

19. Because of its prominence in the design and realization of the

qaṣar-s, the gate has been often accentuated in a semi-pavilioned built-form with decorative friezes (e.g.,

Figure 4). Similarly, in the urban sphere, a considerable number of accentuated gates of some (late-)medieval and early-modern walled cities in Morocco (

casbah-s,

madīnah-s) have been well preserved (e.g.,

Figure 14), and wherever a

mallāḥ existed in both kinds of settlement, it was normally defined by an additional gate (

Figure 7).

Against this background, we would like to draw attention to a particular aesthetic feature that characterizes one of the surviving early eighteenth-century mud-brick gates that encircled the city of Sijilmassa, today part of an archeological site. The gate is crowned by a decorative frieze in the form of a row of pseudo-windows (note that this frieze is made of straight lines in the form of a colonnade, and not of a blind arcade) (

Figure 3). It is unknown, however, whether the style of this gate imitated the gates of ancient Sijilmassa, which have not survived. Interestingly, this particular aesthetic feature—of the gate’s crowning row of pseudo-windows—is repeated regionally in Tafilalt. For instance, it is repeated in the modern gate of Rissani (

Figure 6). Though this (western) gate is a modern creation made of concrete, and though it is hailed on countless travel websites as a jewel of traditional architecture and has become the most photographed monument in the city, it was directly inspired by the older adobe gate in Efroud, twenty kilometers to the north

20. Erfoud’s seventeenth century gate also has a crowning row of pseudo-windows. In its architectural neo-regionalism, Rissani’s main gate also directly corresponds with the city’s older, seventeenth century gates, which again feature the same motif (

Figure 15). This motif is also repeated in the gates of some other Filali

qaṣar-s, some of which are also dated to the seventeenth century (

Figure 4), the time of the region’s revival, and even earlier. For instance, the crowning row of blind windows over the gate’s opening can be seen clearly in two out of the four gates of Qaṣar al-Mansuriyya to the immediate north of old Sijilmassa (the decoration of its other two gates is now in a ruinous state) [

81]. Of them, the first (also the oldest) is dated to the second half of the fifteenth century or the beginning of the sixteenth, and the second (the newest and in current use) to some time in the nineteenth century. Moreover, in terms of building technique and materials, archeologists today closely associate al-Mansuriyya’s first gate with the old site of Sijilmassa [

81]. This means that the Filali architectural style and ornamental features originated in the Middle Ages and continued to be developed throughout the ages, while preserving some of their initial configurations—an argument that is only strengthened by the neo-regional stylistic echoes of Rissani’s modern gate.

This particular feature of the crowning frieze made of pseudo-windows is not typical of the gates of Moroccan settlements in other regions, which were essentially decorated with friezes of other motifs and styles

21 (e.g.,

Figure 7 and

Figure 14). As already mentioned, the motif of the gate that features in many of the Filali-Sijilmassi “residents’”

ketubah-s is characterized by a row of two to four windows in its the upper part. This aesthetic feature is unique to the representation of the gate in the wedding contracts of this region

22, and it does not normally appear in such documents from other regions in Morocco. We therefore suggest an original interpretation by connecting vernacular architectural traditions with vernacular written traditions, by correlating between the Filali three-dimensional form of the gate and its two-dimensional expression in Filali Judaica. Whether both traditions cite an archetypical built-up model gate from ancient Sijilmassa remains an open question due to the lack of specific archaeological evidence.

What can be learnt from such a formalistic and symbolic echoing of neighboring cultures? First, it can testify to the depth of autochthonous identities, their self-determination through patrimony, and their sense of place-making. Yet while the lived-experience and historic heritage of the Filali Arab and Berber majority have been continued to this day without considerable interference, the Jewish heritage of Morocco in general and of Tafilalt in particular is “no more forever” [

25,

30,

83]

23. If we accept the Cambridge Dictionary definition for “nostalgia” as “a feeling of pleasure and also slight sadness when you think about things that happened in the past” (2022, online), we might consider how the Filali-Jewish community has been at least twice displaced

24, and thus has a “double-layered” nostalgia. The “first nostalgia”, of self-definition through patrimony, is being sustained at present by the first and second generations of Filali Jews in their current countries of residence, mostly Israel. It can be dated back to the post-1950s and -1960s periods, when the total majority of this community ceased to exist in Morocco, while its material cultural heritage is still being vividly preserved

25. The “second nostalgia” of self-definition through patrimony can be dated back to the returning of the indigenous (and Jewish) communities to Tafilalt within three hundred years of the fall of Sijilmassa in the late fourteenth century, in the form of decentralized settlements and a series of small

mallāḥ-s. This nostalgia was concretized by the Filali Jewry through at least three expressions: (a) archetypical toponymic self-referencing as “Sijilmassi”; (b) inscribing this practice of referring to a nonexistent-city-of-memory in the

ketubah with relation to wedding ceremonies that took place in all the towns and

qaṣar-s in Tafilalt; and (c) in the

ketubah’s prominent visual image of the gate, which had been employed not only as a classical universal Judaic motif, but also, in its specific design, as a reference to the vernacular architectural heritage of southern Tafilalt.

In this way, these marriage contracts can be perceived as embodying the concept of “place attachment”, as has been theorized in human geography research, where it has been discussed in intimate connection to spatial mobility, dynamism and disharmonious populations transition. Tied with “nostalgia”, the concept of “place attachment” has often been described in human geography as “the emotional or affective bonds between people and places”, with close attention to neighborhood scale and the everyday, and to “processes of meaning-making that transform

space into

place” [

84] (p. 1). “Place attachment” includes elements such as the extent to which residents are dependent on the place to sustain their needs; the centrality of the place in their self-identity through memories and life events; and the residents’ ability to anticipate their mundane interactive routine in the place in the near or distant future [

84]. The last element of special importance is the historiography of the concept, which points to the considerable attention assigned by scholars to situations of displacement and compulsory removals due to environmental, political or economic reasons [

85,

86]. This implies that the concept has been mostly researched in situations where a threat to the residents’ lives in the place pertains, similarly to the changing conditions in Morocco/Tafilalt for the safety of Jews since the 1950s, or to Sijilmassa’s collapse in 1393. “Place attachment” as symbolic capital is therefore a key concept in our material–cultural context, as exemplified. The next section will cast some light on another facet of the Filali Judaic material culture, with interdisciplinary affinity to “place attachment”, spatial mobility, and long-distance trading activity. Here again, the regional

ketubah-s will constitute a starting point, but toward other avenues of exploration.

4.2. The Quincunx: A Mobile Trans-Saharan Motif

Another prominent decorative motif that frequently appears on Filali-Sijilmassi

ketubah-s is the quincunx, which signifies an arrangement of five objects, with four at the corners of a square or rectangle and the fifth at its center (

Figure 16). However, this motif has never been mentioned, identified as such, or interpreted in the meagre research literature about these wedding documents

26; nor in the literature about Filali-Jewry’s material culture more generally, though there are decorative expressions of the quincunx in various material–cultural mediums, such as amulets, jewelry, and fabric (

Figure 17 and

Figure 18). The specific objects that are seen in the latter figures (i.e., 17, 18) for instance, are collected and presented in the Jewish diaspora’s ethnographic collections or local community collections of erstwhile Moroccan (-Filali) Jews in Israel, and are equally represented in the accompanying literature that documents the community’s life cycle and social practices

27. Hence, as traditional objects that had been passed down within the Filali community for generations, mostly as part of the dowry of the Jewish bride, their dating goes back to the date of the attached Figures. These visual expressions testify to the interface between the various ethnic groups that were involved in the trans-Saharan trading activity, through the circulation of people in space, materials and ideas. These expressions also testify, as we shall see, to the sharing of common beliefs and practices, including artisanry expertise such as weaving and iron working, mystical beliefs concretized in talismans and numerology, etc. We assume that the reason for this non-identification of the motif of the quincunx in the material culture of the Filali-Jewry by scholars of (southern Moroccan) Judaism is a lack of an appropriate background in Africa studies. Vice versa, sub-Saharan Africa area studies scholars have not been generally engaged with any aspect of Judaic cultures, philosophies or artistic expressions [

25,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]

28. Still, tracing the paths of traffic of the quincunx between the visual legacies of different groups to the north and south of the Sahara Desert, the full meaning of this motif and its symbolism constitutes a riddle, and is subject to a wide range of interpretations.

For instance, in a study of the wall art of Walata (eastern Mauritania, see “Oualata” in

Figure 2), a major caravan city situated on the route from Timbuktu to Sijilmassa, the anthropologist John Shoup documented a variety of quincunx configurations [

88] (

Figure 19, left). The history of this motif in Walata is assigned to the period between the Almoravids, via exiled Andalusian Muslims, to dynamic developments in the present. While Shoup has not identified this motif explicitly as a quincunx, he has managed to pioneeringly typologize it according to societal use, location within the residential unit, and meaning accorded by the house-users. The open-courtyard houses, made of stone, are coated with a thick layer of reddish clay, on which the colorful designs are inscribed by professional women artisans in certain key areas on the outer and inner walls, such as around the openings. The rich variety of indigenous quincunx symbolism includes representations of a foundation stone and water drain, as well as purification, marriage or fertility prospects, and God’s blessing. Shoup points to a possible, though unproven, equivalence to some Jewish practices (such as the

mezuzah charm placed on the doorway, an element that existed in the city in these parts) and to similar designs seen in Saharan historical manuscripts (such as quincunx roundels). Other inspirations for these designs are associated with an Andalusian heritage and with medieval southern Sudanese kingdoms such as Mali and Ghana [

88] (pp. 186, 188, 191). In another context, the ethno-mathematician Ron Eglash assessed the West African (assumingly Wolof) roots of the African-American Benjamin Banneker, through the latter’s mathematical thinking [

89]. This is through his employed numerology and geometric system, some of which was consciously based on quincunx riddles. Identifying the quincunx as a most pervasive religious symbol in Senegal, Eglash commented on the two-dimensional expressions of this motif in vernacular ancient and contemporary designs, mainly Wolof. These include, among others, amulets, floor tiles, prayer mats, and iron and leather works (

Figure 19, right). He also commented on this motif’s Islamic indication as “the light of Allah” (e.g., in the city of Touba), and on what he assigned to pre-Islamic, “original” indication as “power radiating in all directions” (e.g., in Burkina Faso) [

89] (pp. 311–315). The time span between historically rooted traditional quincunx designs and the modern expressions of these designs testifies to the significance of the quincunx motif at a regional level and to its aesthetic patrimony, at the same time as being a commonly used geometric pattern that characterizes the area. This somewhat echoes the neo-regional stylistic revival of Rissani’s gate, which is further exemplified in the following.

The only scholar who has dealt so far with the quincunx and its derivative forms as a concept, with full attention paid to the vast region in question, as far as we are aware, is the art historian and architect Labelle Prussin. In her monograph

Hatumere (1986) [

90], she analyzed this motif with relation to the Islamic magic square construction and divination system, and identified it as

khātam in Arabic (and

khotam in Hebrew), which means “seal”, from which the Fulbe singular

hatumere (borrowed for her book title) derives. Containing several layers of possible meanings, this grapheme has been identified with West African Islam since late medieval times, and has been also inspired by the

kabbalah, which is a school of thought in Jewish mysticism originating in twelfth and thirteenth century Spain and Provence (Southern France), and which had spread to North Africa and the Sahel by the sixteenth century [

25]. Designed as a three-by-three (or four-by-four) nine-house square, this geometric configuration, known by the name “Allah”, constitutes a popular regional design. It appears in a two-dimensional form, such as in amulet designs, prayer books, clothing embroidery, and leather works, as well as in three-dimensional form, such as in architecture in hut design, ground plans of houses, and medieval city plans (

Figure 20A–E). In the town plan of Timbuktu, for instance, the quarters’ layout is intended to mirror the cosmological system with relation to the Polaris, a configuration that is also inherent in the very definition of the “quincunx” in astrology as an angel of 150° between two planets [

90] (chs 4–5). Another cosmological touch is hidden in the quincunx design of the “Agadez Cross”, an object that facilitated the spatial orientation of caravans in their journey across the Sahara through the night. The caravan guide used to hold this amulet–compass object in a certain position against the sky, while positioning parts of the “cross” in relation to designated stars

29 (

Figure 20F). As clearly exemplified by Prussin, this historical conceptual motif has been shared, with changing geo-contextual possible meanings, among a variety of groups on both sides of the Sahara, particularly in today’s Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea, Gambia, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Cameroon. Here again, the regional visual consciousness seems to enable an interplay between historical quincunx designs and recent configurations. Layers of interpretations accumulate into an ever-dynamic popular vernacular knowledge. Throughout the Mandingue (Mandinka) region, for instance, the calabash flower is represented by the quincunx and symbolizes material wealth (

Figure 21, right). According to a recent oral source, the head of the conservatory of natural dyeing techniques in Ségou, Mali, the quincunx/calabash flower constitutes one of the twenty basic symbols in the Mandingue aesthetic repertoire

30 (

Figure 21, left).

5. Conclusions

By mediating between different mediums of material culture in the Tafilalt region in southeastern Morocco, such as architecture, minor art, and manuscripts, this article demonstrates the dissemination of ideas and the cross pollination between the various groups that are native to the region. As part of a shared tradition of the organization of long-distance, trans-Saharan trade infrastructure, these groups (Berbers, Arabs, Jews, Sahelian and sub-Saharan Africans) intersected with each other in multifaceted ways, such as in the Tafilalt through retail and wholesale commerce, completing professional (in terms of transportation, artisanry), ethno-cultural, political and religious negotiations in more (or occasionally less) harmonious ways, and side-by-side residence in a variety of spatial expressions. Historically, from at least the eight to the fourteenth century, this long-distance trade infrastructure was centered on the city of Sijilmassa, which connected the world north of the Atlas Mountains with Black Africa, through the advantage of its physical location (on the frontier of governmentality, which resulted in a special ethno-political climate, and as an immediate pre-Saharan oasis). Despite the fall of Sijilmassa at the end of the fourteenth century due to considerable political instability in the Tafilalt, and despite unsuccessful attempts at its revival in the seventeenth century, it is safe to argue that the human settlement there has been continuous almost without interruption. The prolongation of Sijilmassa was pursued through the gradual rise of the present regional capital of Rissani (with the support of the Makhzen). Whether a centralized urban settlement surrounded by two walls (Sijilmassa), or a decentralized urban organization in the form of many dozens of sporadic quasi-village-like qaṣar-s in Rissani’s metropolitan area, there has been a continuity of human settlement in Tafilalt. The oral history of indigenous groups, partly documented, also supports assumptions of this continuity in terms of the original core of Sijilmassa’s communities.

Within this tapestry of pre-Saharan crossroads, and elements of mobility, transition, and intra-group cross-pollinations throughout the ages in southeastern Morocco, the indigenous Jewish community was an important agent in shaping the region’s landscape. Its presence characterized both historic Sijilmassa and modern metropolitan Rissani with its dozens of qaṣar-s, at least until the 1950s and 1960s. Fascinatingly, although the city of Sijilmassa today is an archeological site with few remains, and its name is no longer in regular use for orientation among the autochthonous resident groups in the Tafilalt, the Jewish community that had been scattered in small settlements all over the region preserved the name of the original settlement, Sijilmassa, and continued to define itself and its identity through it, for halakhic reasons. This habit continued in parallel with their use in the toponyms of Tafilalt and Rissani, and those of each qaṣar (and it continues today in the diaspora as well, especially in Israel, as an expression of identity). Our analysis of the world of aesthetic imagery as appears on the ketubah, the Jewish marriage contract, in its Filali version, reveals the richness and uniqueness of vernacular symbolism. As shown, this symbolism is cosmopolitan-cum-local as it is inspired by: (a) the world of global Jewish imagery; (b) Morocco’s architectural heritage and that of surrounding Tafilalt; (c) the conceptual imageries of other groups in the Sahel and sub-Saharan Africa, though it is impossible to trace the actual channels of inspiration in a teleological way.

In order to be able to better read the pre-Saharan environment and its correspondence with Judaic textual and aesthetic conceptions as embodied in the manuscripts in question, and to “read” and decode their visual repertoire, a transdisciplinary approach must be employed. The article has brought together research historiographies that are not normally intertwined, in an encounter that throws a new light on the study of Filali Judaica. This is achieved by crossing area studies (of both Middle East and sub-Saharan, Black, Africa), cultural studies (of both Muslim and Jewish cultures), and art history (of both architecture and minor arts including manuscripts); and with the prospect of seeing more of such interdisciplinary studies in the ongoing journey of exploring the variety of “flows” of human intercultural dissemination that have crossed the Sahara Desert. In this way, new avenues are opened through multidimensional “nomadic” discovery, which welcome innovative observations of the world and unexpected crossovers.

Today, the mobility potential of Morocco’s erstwhile large Jewish population seems to have another use by the Moroccan government, who are utilizing it to build bilateral infrastructure for tourism, based on cultural assets. Following the establishment of Israeli–Moroccan diplomatic relations in 2020, a direct Tel Aviv–Casablanca flight has been initiated by Royal Air Maroc. Well aware of the fact that Israel is the country where the largest number of Jews of Moroccan descent live, among them about 150,000 Jews whose country of birth is Morocco, and another 340,000 whose father was born there [

91], let alone the many Israelis who are third-generation immigrants from Morocco or alternatively with a partial family background situated there, the company came up with the slogan: “Welcome to your Country!” In this way, the cultural assets and history of an uprooted community [

92] are turned into an increasing economic asset by modern state politics and policies. Morocco aims to double its tourism sector from 10.3 million (2016) to 20 million (2020) tourists visiting annually; the number of Israeli tourists in Morocco currently stands at between 25,000 and 40,000 annually, mainly though organized tours, and is expected to triple [

93] (p. 9)

31.