1. Introduction

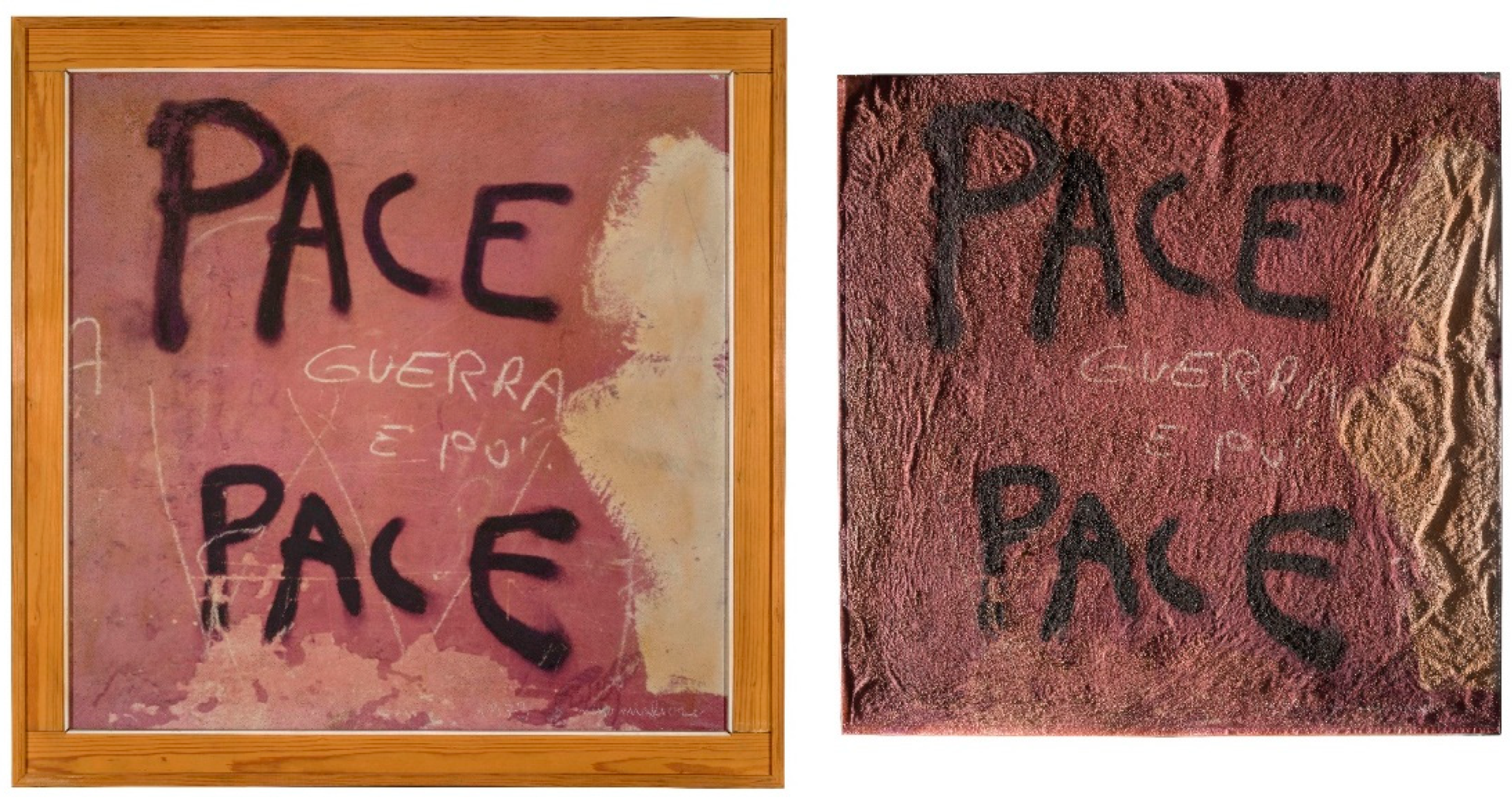

Pace (

Figure 1) can be described as one of the most experimental artworks created by Nino Migliori. It is part of

Walls, a very significant series of the author’s production, and, since 1975, it has been included in the permanent collection of MAMbo—Museum of Modern Art of Bologna [

1]. What makes

Pace so peculiar is the fact that it is a photo-based artifact, which means it has the characteristics and conservation necessities of both a contemporary artwork and an object of experimental color photography.

At the beginning of 2020, after a state of conservation assessment, Pace was evaluated as being in urgent need for conservation treatment and for this reason, in July of the same year, it was transported to the Conservation Laboratories of the Conservation Department at the Fine Arts Academy of Bologna. Due to the complex structure of the artifact and the uncommon materials used by the author, an extensive preliminary study phase was considered necessary before starting to plan the conservation treatment. Although it was conducted as a fundamental preliminary step in developing an intervention methodology to address Pace-specific conservation issues, it is believed that this approach could be a valid starting point for the analysis and treatment of other contemporary photographic objects with similar types of mountings. In addition, the same study and treatment methodologies could be applied to the issues encountered on the numerous artworks included in the Walls series examined throughout this study. The examined artifacts were created with similar techniques but, in most of the cases, they presented a simpler structure with fewer layers as a result of a less complex artistic experimentation process. Both the in-depth research and the conservation treatment were conducted in the context of a master’s degree thesis project and this paper intends to explain in detail how the examination, analysis and treatment of this experimental artwork of contemporary color photography were carried out.

2. The Preliminary Research on Pace: Introductory Remarks and Final Objectives

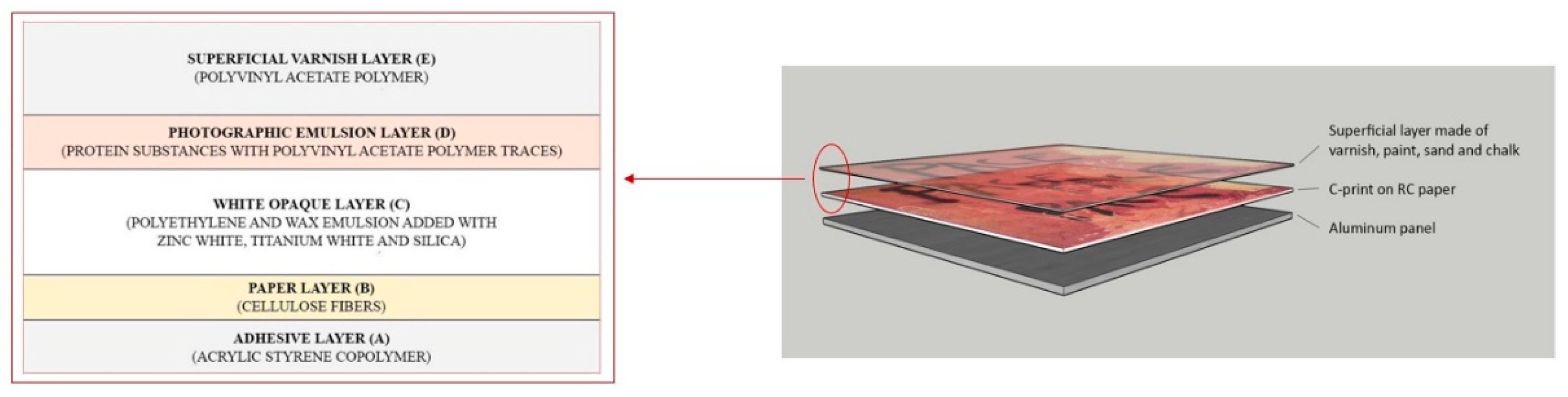

Pace consists of a large format c-print (100 × 100 cm) mounted on an aluminum panel by the author himself in a unique and complex making process. During the preliminary study phase, the focus has been mainly on the analysis of the structure of the artwork and the characterization of the materials used by the artist.

Pace, which was created out of a photographic print (hence, making it reproducible in theory), is actually an unicum, namely the sole existing exemplar of this specific kind of artifact. From the beginning, it became apparent that the understanding of the structure would not be easy since

Pace showed a layered structure (

Figure 2) in which the overlays appeared merged together.

The author Nino Migliori used this print as a starting point for his experimentation and he used different kinds of media and techniques to create a completely different and unique artwork. He intervened not only on the surface of the print, but also underneath it and on the mounting. The objective of this process was to recreate the appearance and the perception of the wall he shot and he succeeded in this effort in an extremely realistic way. In order to plan and perform an adequate treatment to solve the conservation issues encountered, such as detachments, planarity distortions and mechanical damages, which was indeed the ultimate purpose of this project, an in-depth research preliminary phase was deemed necessary. This research was conducted in three phases, each with the aim of analyzing a particular aspect of the artwork’s creation. The first phase entailed a thorough literature review on the series of Walls, with the purpose of understanding and contextualizing the artifact within the author’s production as far as possible. Subsequently, the second part of the research allowed one to precisely reconstruct the process behind the creation of Pace, providing fundamental insights for the study of the execution technique through direct examination of the artwork and data gathering through research and interviews. Eventually, in the third and last phase, the more technical aspects of the artwork’s creation were addressed, focusing on the materials’ characterization, the identification of the photographic technique and the definition of the component layers’ stratigraphic sequencing, using both non-invasive and micro-invasive diagnostic techniques.

3. Nino Migliori and the Walls Series

The photographer Nino Migliori was born in Bologna in 1926 and started shooting in the late 1940s. To this day, he is one of the most active experimenters in Italian photography and his production is one of the most varied and interesting in European image culture [

2]. His heterogeneous production is made up of both canonical photographs in documentary style and incredible experiments, such as the

Walls series. Throughout his career, the contact with contemporary art and artists has been fundamental to his experiments in photography; in fact, while they cannot be traced back to a specific period of his production, experimentation can be considered more a method or a line of research that he has never abandoned to this day.

Walls can be considered one of the founding series of his production and during the thirty years of shooting mural surfaces, from 1949 to the late 1970s, Migliori has investigated the walls in an original way and from different points of view [

3]. The author himself stated that he always approached the walls he shot without much interest in planning ahead, but in retrospect it is perhaps possible to divide his production into three periods. Initially he was driven by curiosity about marks on walls, then by interest in stains and molds, and toward the end by the concept of writing on walls. This was a time when the author considered the wall a real medium for writing, for communication and also for gestures [

4].

Pace was created during the last period and this first part of the research made clear that, among the artworks of the same years, it is definitely one of the most experimental.

4. Reconstruction of the Creation Process through Direct Examination and Interviews

The second phase of the research focused on the reconstruction of the artifact creation process and on the identification of the print photographic process. The initial step to reconstruct the creation process was the direct examination of some other artworks from the

Walls series, mostly housed at the Nino Migliori Foundation in Bologna [

5] (IT), at the Museum of Contemporary Photography (MUFOCO) [

6] in Cinisello Balsamo (IT), and at the Study Centre and Communication Archive (CSAC) [

7] of the University of Parma (IT). After careful examination of the artworks, it became clear that the execution technique of

Pace was very peculiar; among the examined objects,

Pace was the only one showing that type of material application, made of sand and mixed media, above and under the print layer. The following step was to interview people connected to

Pace and its creation, such as Paolo Barbaro, Nino Migliori and Marina Nella Truant. Paolo Barbaro from CSAC has collaborated for years with the author Nino Migliori and the Studio Villani, a renowned photographic studio in Bologna, where Nino Migliori used to print his color photographs [

8,

9]. He provided important information on the materials and techniques generally used by the printers of the Studio Villani, allowing one to formulate an initial hypothesis on the print photographic technique. All the information he delivered was confirmed and enforced during a later interview with the author himself (

Figure 3) and with the Director of the Nino Migliori Foundation, Marina Nella Truant. They both provided fundamental insights on the artistic and social context in which Nino Migliori conducted his experimentation. On this occasion, it was made clear that the print was not only mounted on an aluminum secondary support, using a vinylic-based adhesive applied with a brush, but that it was also manipulated by the photographer, who experimented on the artifact by applying sea sand of different grain sizes above and below the print. Nino Migliori also made use of other media, such as chalk, varnishes, and synthetic paints, with the aim of emphasizing some graphic elements of the photograph so as to give it a realistic appearance, resembling the wall surface.

As regards the identification of the photographic technique, there were certain factors which complicated the visual examination of the print. First of all, the whole surface of the photograph appeared covered by a thick layer of mixed media which included chalk, pigmented paint and sea sand; therefore, the image layer of the print could be observed only through the cracks and losses of the mixed media superficial layer. After careful examination of the image layer in those points, it became clear that the surface was too compromised by the author’s intervention and the observation was deemed inconclusive. Then, the back of the photograph was completely cloaked by the aluminum secondary support; therefore, it was not possible to observe the back of the print nor to identify any back printing related to manufacturers and type of photographic paper. The only indication that could lead to the identification of the photographic technique was the examination of the signs of deterioration, which, in most cases, refer to specific photographic processes. Starting from this consideration, a literature search about typical alterations of color photographic materials was carried out in order to compare the conservation issues found on this print with what could be found in the literature [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. This part of the research revealed a paucity of information in the literature on deterioration of photo-based contemporary objects. This factor, along with the substantial lack of presented case-studies and intervention methodologies for the treatment of similar artworks, has brought crucial attention to some challenges and difficulties for the conservators. At this point of the research, the most relevant information were the data gathered through the interviews, especially regarding the materials and photographic processes commonly used at Studio Villani, along with the direct examination of the photographic alterations which could be observed on

Pace. This led to the assumption that this contemporary artwork was made out of a chromogenic print or c-print, a common color photographic process used from 1942 to the present [

14]. Confirmation of this hypothesis was sought through an analytical approach for the identification of the photographic process.

7. The Treatment of Detachments and Lifts of the c-Print from the Secondary Support

To perform a safe and effective conservation treatment, the elaboration of a new intervention methodology was necessary to address the severe alterations observed on the artwork, bearing in mind its peculiarities as a photographic object and a contemporary work of art.

Before starting to treat the detachments of the print from the aluminum panel, it was necessary to conduct some cleaning operations to remove potentially harmful surface dirt and to improve the chemical and physical stability of the superficial layer. The artwork framing did not include a protective glass; in fact, its surface was in direct contact with the frame and therefore exposed to any kind of environmental factor, such as dust and dirt. Although the artifact had been kept in a museum environment approximately since its creation, a light layer of dust and particulate air pollution had nevertheless deposited on the surface. It was therefore considered essential to proceed with cleaning as the first step of the conservation treatment, choosing materials and methods compatible with the chemical and physical characteristics of the artwork surface. The choice of cleaning materials was oriented towards the ones suitable for photographic objects’ cleaning, while being soft and adaptable to the superficial layer morphology. The artist applied sea sand on the artwork surface and the superficial layer presented some cracks and losses; thus, it was fundamental to perform the cleaning operation in a gentle yet effective manner in order to avoid altering this fragile surface.

The cleaning was performed in two phases: dry-cleaning and hydrogel cleaning.

The dry-cleaning [

18] operation was carried out using a polyurethane sponge specifically designed for conservation, which was used to clean the surface with light and gentle strokes (

Figure 18). Its characteristics, such as flexibility and softness, made it possible to carry out an effective cleaning while simultaneously respecting the complex surface morphology of the superficial layer. The compact micro-porous structure of the PU sponge was proven to be particularly suitable for removing the finest dirt residues.

The hydrogel cleaning was performed using high water-retention viscoelastic PVA-borax hydrogel at 8% [

19]. This is a transparent and non-adhesive gel that can adapt to surface irregularities under very light pressure, thanks to its particular malleability and specific viscoelastic properties. This type of hydrogel has a high water retention and therefore a reduced wettability, which allowed us to perform a safe and effective cleaning of the surface (

Figure 19).

The treatment of detachments was addressed after these preliminary cleaning operations. Before the conservation treatment, the c-print was unevenly detached from the underlying aluminum panel and addressing this problem was the main focus of the treatment. At first, the possibility of completely detaching the photograph from the underlying aluminum panel by using solvents was considered, but this procedure would have compromised the original adhesive and sand layer, leading to the displacement and loss of most of those materials. For this reason, the methodology elaborated still comprehended the use of the solvent but it was not used to remove the print from the secondary support in this case. The application methods described below made it possible to use solvent to reactivate the original adhesive, allowing one to preserve the glue and sand layer while working on the re-adhesion of the print. The methodology elaborated to address this conservation problem consisted of two phases: the first, concerning the solvent reactivation of the original adhesive with ethyl acetate, [

20] and the second, involving the addition of small amounts of Plextol B500 adhesive in demineralized water (1:1 ratio) to the areas of the artifact where the reactivation of the original adhesive alone was insufficient. Initially, the re-adhesion of areas with minor detachments was addressed, starting from the most internal areas on the left of the artwork and gradually moving closer to the edges, in order to limit the retention of solvent in the internal areas and facilitate its evaporation. In the most inaccessible areas, ethyl acetate was applied through injections of calibrated amounts in proportion to the extent of the detached area, while the application was done by brush at the edges (

Figure 20).

The amount of solvent to inject was calibrated through some empirical tests, in which the 0.1 mL of ethyl acetate was spread on a flat glass surface. The diffusion of the solvent was measured in centimeters in order to approximately assess the spreading of ethyl acetate when injected onto a flat surface (

Figure 21). Whether the measurement of the diffusion on the glass did not take into consideration the swelling of the original adhesive and the presence of sand, it was still possible to use the results of this empirical test as a guide to calibrate the amount of solvent to inject in each area. The same test was carried out to measure the spreading of the Plextol B500 solution in order to calibrate the adhesive injections as well.

After this operation, the areas were placed under weight until complete evaporation of the solvent, which, despite its particular volatility, took several days in most cases. The weights were applied to the surface of the artwork initially by interposing Melinex monosiliconate sheets in order to prevent direct contact between the photographic print and the weights used (

Figure 22). Once the setting time of the reactivated original adhesive had passed, the artwork was placed again under weight, this time interposing some non-woven fabric sheets and felts to facilitate the evaporation of the solvent through more permeable layers.

The cushioning effect of the felt layer allowed one to exert an effective yet gentle pressure on the surface while preserving the morphology of the artifact superficial roughness (

Figure 23). This operation was carried out over the entire surface of the artwork affected by the detachments; once the solvent had completely evaporated, it was noticed that the reactivation of the original adhesive alone was insufficient in some areas.

Those areas were mainly located on the right side of the artwork, characterized by the most severe detachments and alterations in flatness, as well as at the edges of the work of art, where the original adhesive was almost absent due to the fact that it was unevenly applied by the author using a brush. The remaining detachments were treated with the application of a conservation adhesive which consists of an acrylic dispersion in water. In this case, it was decided to apply Plextol

® B 500 adhesive with a brush at the edges and through injection in the internal areas after diluting it with demineralized water (1:1) to facilitate the injection. Throughout this operation, any micro excesses of adhesive that had leaked from the edges or injection holes were carefully removed with a damp cotton swab to avoid causing any kind of alteration on the artwork surface. The selection of an aqueous, solvent-free dispersion adhesive, used to treat the areas where the organic solvent was found to be ineffective, was made to ensure a confined treatment to the detached areas, as the injection of a solvent-based adhesive could have caused the occurrence of further detachments in areas previously unaffected. This is for two reasons: first, the solvent diffusion through the original adhesive layer would have not been easy to control, due to the affinity of the adhesive with organic solvents; and second, the characteristic high viscosity of solvent-based polymeric solutions would have been an obstacle in the injection phase, leading to the use of more diluted solutions and therefore the injection of larger amounts of solvent, increasing the risk of creating new detachments [

21]. During the drying of the adhesive, the same precautions were taken as in the previous solvent evaporation phase. It may be important to point out that the operations described were carried out extremely gradually, over several weeks, during which the time required for complete drying and total evaporation of the solvent was given to the materials. The time frames needed for the drying of the original and the new adhesives were evaluated taking into consideration the ethyl acetate and water volatility and by carrying out empirical tests of solvent evaporation through layered materials similar to the one of the artwork in the same environmental conditions. The strict compliance of the necessary time frames was decisive for the effectiveness of the intervention, while respecting the constituent materials of the artifact, which, at the end of the operation, appeared unaltered in their physical and aesthetic consistency (

Figure 24).

In addition, the artwork was monitored during every stage of the treatment through the observation of the surface in raking light, which made it possible to intervene safely, with a high degree of awareness and control of the immediate effects of the products used and their application methods. At the end of the intervention, it was possible to notice how the combined action of the two methods described above made it possible to achieve an optimal result in the re-adhesion of the photographic print to the aluminum panel, and how the controlled drying underweight allowed it to regain the flatness of the print (

Figure 25).