1. Introduction

Shoes and boots, as well as clothing, meet one of the basic human needs: protecting the body from the climate and the habitat in which we move. As a result of technical development and the exploitation of different manufacturing materials, the organization and corporate specialization of artisans linked to the production of footwear and the growing demand for individualization (even if expressed through group membership), footwear has become a differentiated object, creative and representative of each individual’s social status [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

The obvious fact that most male and female inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula in the Early Modern period wore footwear is in inverse proportion to the number of studies addressing this issue and, therefore, to the quality of our knowledge about this subject. In fact, the study of the history and manufacture of footwear has aroused little interest among Iberian historians and archaeologists. In the absence of original and well-preserved specimens in public or private collections, archaeologists have chosen to disregard the abundant remains recovered in excavation contexts. These remains being abundant, we must acknowledge the reasons that have justified such a choice. On the one hand, the amount of incomplete remains recovered in archaeological contexts and the absence of a strategy for managing and including these particular typologies in collections has sustained a conservative policy limited to the identification of the materials used, counting the number of similar items, indicating the dimensions and providing an approximate description of the typology (shoe, boot or sole) of the objects. On the other hand, the dispersion of archaeological interventions (mostly emergency salvage work or interventions with limited specifications) and the complex preventive conservation of this type of objects, made of organic materials, hinder the storage and further study of the remains, resulting in the subsequent disposal by teams of archaeologists and heritage managers.

Likewise, visual and written sources are also scarce or difficult to interpret. In Portuguese visual heritage, particularly sculpture and painting, the representation of footwear is not abundant since there is scarce genre painting, and most of the depictions refer to reconstitutions of public and religious environments in which men’s shoes and boots are not very distinctive or detailed, and women often have their feet covered by gowns [

8]. Moreover, the written documentation, despite being descriptive, tends to be limited to clothing, with little mention of footwear and, above all, little detail regarding its technical and formal characteristics [

9]. See, for example, the inventory of the dowry of the Infanta Beatriz (1522), which was the motto for the DRESS project (Designing fashion from 16th century sources) and which describes the objects, and also the trousseau, taken by the Portuguese princess to the court of Savoy on the occasion of her marriage to the duke. There must have been shoes among these objects, namely the well-known chapins (chopines) worn by the ladies of the Iberian court, yet there is no record of any pair of shoes in the entire inventory [

10] (pp. 122–142).

The DRESS project (2019–2022;

https://vestenovafcsh.wixsite.com/websiteen/dress, accessed on 18 December 2022), whose aim was to study the process of making a garment based on the descriptions of the inventory of the dowry of the Infanta Beatriz of Portugal (1504–1538), was a key moment for the analysis and reflection on the results presented herein. Indeed, the project brought together a multidisciplinary team of researchers who asked the same questions at different moments and who had access to the archaeological remains and data recorded in excavation reports. Given the absence of written data in the inventory and of visual representations that might provide information about the footwear worn by the infanta, we were interested in trying to understand what type of footwear was worn at the Portuguese court in the first half of the 16th century. We resorted, therefore, to the archaeological information that was known to exist, but had never been analysed.

In this context, the excavation conducted in 1998, in the bay of Angra do Heroísmo [

11] (pp. 199–210), [

12] (pp. 211–232), and the consequent reports on the Angra D shipwreck (hereafter ANGD), a 17th century vessel sunk in the Azores, provided relevant data regarding the quantity/quality of the different forms of shoes recovered. The remains found at ANGD had a significant advantage: they could be extrapolated to the Iberian context, given the associated material culture, namely Andalusian ceramics and mercury. On the other hand, the absence of similar studies for the Spanish case encouraged extrapolation, also made possible by the dynastic and cultural proximity between the Portuguese, Castilian and Aragonese crowns, which, having always been significant, became even closer in the transition from the 15th to the 16th century, following a series of marriages between members of the Portuguese and Castilian lineages with first-degree kinship, a ‘dynastic obsession’ [

13] (p. 99) which would culminate in the governance of both crowns under a single dynasty after 1580.

Even so, and as we shall see further on, the identified and studied ANGD artefacts continued to raise issues from the point of view of the characterisation of the DRESS project, since there were no remains that could be unequivocally identified as being of female use. Thus, case studies with similar archaeological characteristics were added, in order to broaden and diversify the information about shoe forms and their associated chronologies. Two other archaeological sites were chosen: the Santa Clara-a-Velha (Poor Clares) Monastery (hereafter SCV), located in the South bank of the Mondego River and abandoned by the nuns in 1677, and Campo das Cebolas (Old Market, hereafter CCLX), a Lisbon urban market site where land has been gained from the river since the 15th century. These three case studies were deemed representative because they not only portray different daily life contexts but also share similar archaeological features: humid or waterlogged environment contexts where the preservation of organic materials, such as leather, cork, or wood, has been secured.

This will be a contribution to the classification of future findings and also to the knowledge of Iberian fashion. With this goal in mind, we gathered information on shapes, sizes, uses, construction techniques and materials used, as well as their social and environmental contexts [

14].

Although the Iberian Peninsula features specific footwear characteristics, such as the chopines, and given the precarious development of these studies for the Iberian world, the critical bibliography about the formal and technical development of footwear, mainly related to findings from Northern Europe, is a methodological and narrative tool for the elaboration of this paper, since it has been testing different approaches and consolidating interpretations about the various footwear typologies and shapes, associated to different social contexts and uses.

By addressing these three identified and well-preserved leather footwear assemblages, we aim at both their conservation, the development of academic interests on the different types of materials recovered in archaeological excavations and a change in the corresponding heritage management solutions.

2. Historical Context

The history of footwear and the shoemaking craft in Early Modern Portugal, including its branches, such as chapineiro (i.e., a shoemaker specializing in chopines), is yet to be written. If, on the one hand, the craft has been studied from the point of view of the characterization and social organization and the technical development, on the other hand, a synthesis or even an overview of footwear history itself is still missing. The few existing studies on materials, techniques and manufacturing methods are dispersed and do not support the establishment of a sequential and interpretative narrative of the history of footwear in Portugal, despite the relevance of this industry to the country’s economy. We would highlight, in this context, the finding of an important footwear production unit in Guimarães, in Northern Portugal, where several structures were identified, including tanning vats in the leather area, related to the assets of the Shoemakers’ Guild and Hospital, dating from the late 15th century [

15] (pp. 8–57). Footwear, whether from a heritage point of view or in terms of historical or archaeological analysis is, therefore, a subject without visibility.

The shoemaking craft was included in the type of artisanal activities carried out in autonomous workshops which, in turn, were collectively integrated into the so-called guilds or corporations, whose purpose was to define the quality and manufacturing standards, the requirements for learning the trade and the regulation of the business itself, i.e., determining who could open a shop as the master of a particular trade [

16]. The coeval corporative system did not extend beyond the municipal territory and was therefore under the jurisdiction of the municipality, which had some say in its decisions. Even so, there was some autonomy towards the existence of a corporative self-regulation in terms of prices, quality, production and distribution of goods in relation to the municipal and royal powers, which allowed meeting the aspirations and interests of shoemakers as an economic group.

The oldest known regulation in Portugal pertaining to borzeguineiros (buskin makers; a type of boot with a knee-high shaft), sapateiros (shoemakers), soqueiros (mule makers) and chapineiros (chopine makers) dates from 22 September 1489. On 13 September 1532, a new regulation was issued to regulate the shoemakers’ activity, this being a logical consequence of the importance and meaning that the footwear sector was reaching in the Portuguese kingdom and of the concern in trying to regulate this craft. Despite the persistence of a certain disorganization of the crafts until the end of the 16th century, this was an attempt to differentiate the specialized trades and to meet the consumption needs, while assuring that the type of footwear made by shoemakers, clog makers, chopine makers and buskin makers had the best possible quality.

According to Friar Nicolau de Oliveira’s book Livro das Grandezas de Lisboa, in 1620, there were 864 ‘sapateiros da obra nova’ (i.e., shoemakers who actually made shoes), 60 ‘sapateiros de calçado velho’ (i.e., shoemakers who mended used shoes) and 20 ‘sapateiros de chapins dourados’ (i.e., chopine makers). The number of shoemakers, much higher than all the other crafts, illustrates the conspicuousness and consumption variety of these everyday objects in the city of Lisbon.

In the context of footwear production, the case of chopines in Iberia deserves to be highlighted, namely in the scope of the project and artefacts presented and discussed in this paper. Nicolau de Oliveira recognized it in the early 17th century by singling out the chopine makers from the rest of craftsmen who made or mended shoes. This specialisation among professional shoemakers confirms the widespread use of this type of shoe, exclusively feminine, among the population. Indeed, its use was probably common among several social groups, since courtly consumption would hardly justify the existence of such a large number of professional shoemakers (n.b. the figures mentioned above only pertain to Lisbon). The reasons for this fact are still to be ascertained, but the abundance of the materials used in the manufacture of the sole and height of the shoe, specifically cork, and the objects and practices that remained after the long Arab presence in the Iberian Peninsula (711 to 1249 in Portugal and 1492 in Spain) may contribute to the justification. Moreover, chopines were also common in several regions of the Italian Peninsula, where both the Arab presence and the commercial exchanges within the silk routes and the contacts with the Ottoman Empire were recurrent.

Chopines have been interpreted by historiography as objects of otherness, symbols of status and Iberian dynastic identity [

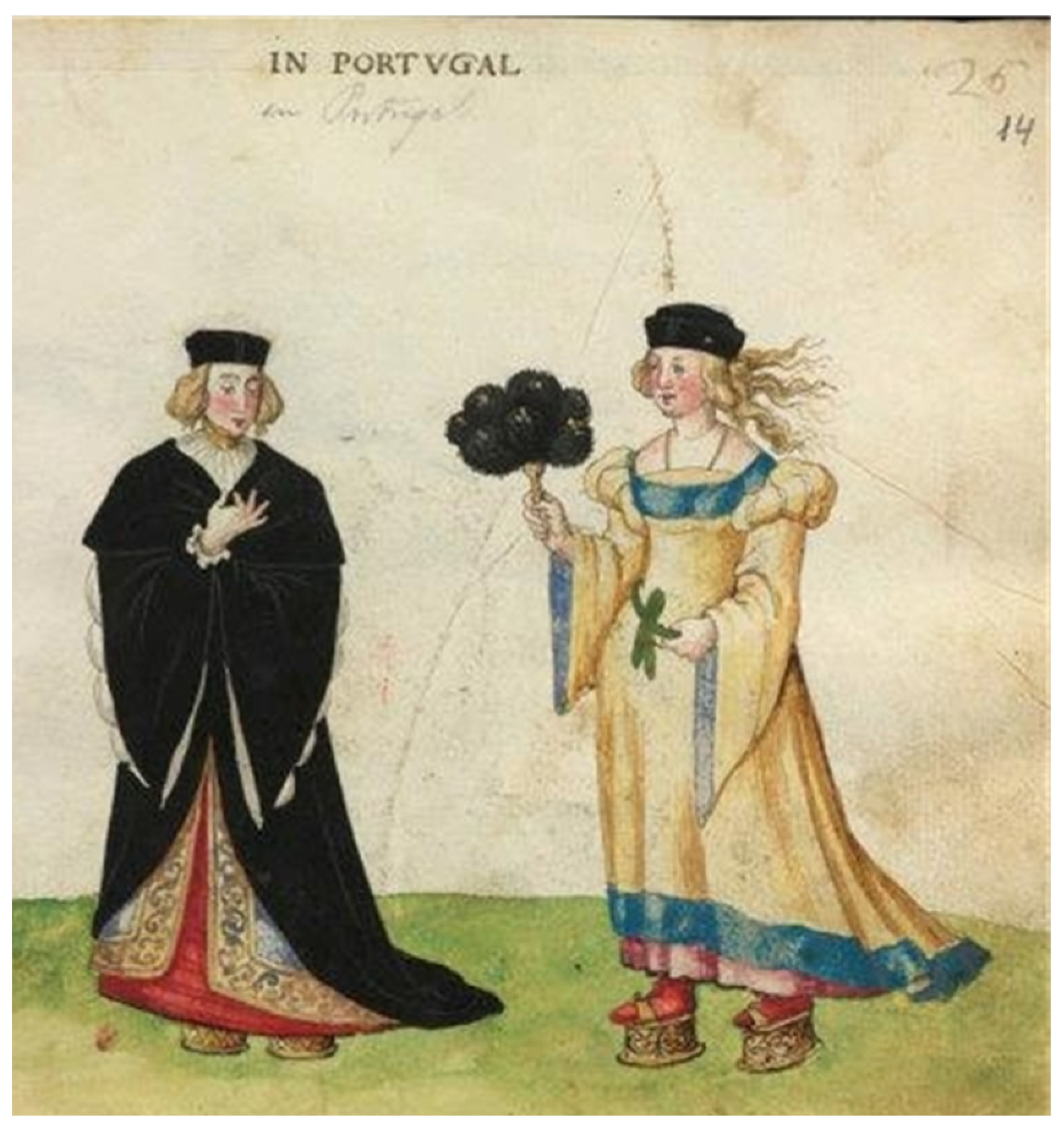

17], and a synthesis on its materiality is non-existent. There is an absence of written and visual Portuguese and Spanish documentation that might contribute to this synthesis, so it is not surprising that the representations of chopines appear mainly through the eyes and by the hands of foreign travellers in the Peninsula, as can be seen in

Figure 1. In this sense, the presentation of the archaeological results discussed in this paper is relevant for the construction of a formal and material knowledge of this type of artefacts.

Even though there are records of shoemakers’ shops in several areas of the city, most of them and the most famous ones were concentrated in Rua Nova (New Street) and Rua dos Douradores (Gilders Street) streets, according to the inquisitorial procedures, which support an effective mapping of the trades performed in Lisbon throughout the modern period [

15,

18,

19].

3. Organisation and Manufacturing Techniques in the Portuguese Context

In Portugal, the tanning of hides used mainly sumac—a shrub about three metres high, with round, reddish fruits containing a large amount of tannin—and oak bark, which resulted in a strong, hard leather that was used to make shoe soles. Tanning with sumac resulted in a softer and more flexible leather, which was not suitable for making soles, but could be used for lining shoes. Water was another essential substance for shoe making, since it was used to soften and make the leather flexible and mouldable to the shape that it kept after drying.

The sole is the basis of any type of footwear, because it is the part that has to bear the weight of the body and direct contact with the ground, and it is therefore the one that suffers the most wear and tear. This is where the thicker and more resistant leathers are used. Soles were usually made of cow or ox leather, but cordovan, i.e., male goat and sheep hide, could also be used [

19] (p. 9). The footwear manufacturing process was widespread throughout Europe [

20], adapting to the most accessible materials in each region.

The first task was to execute the cut of the shoe, which required shaping and cutting the leather for several different parts that compose the shoe, using very sharp knives, called trinchetes or shoemaker’s knives. Another very useful tool was also used, the coarse textured rasp or file, which was used to scrape and trim the soles. The different parts were sewn together and then assembled in a wooden mould shaped like a foot. These moulds were made by the mould makers in various sizes, according to the shoes that shoemaker made to order (

Figure 2).

The most important part of the cut was the upper part of the shoe, the vamp, which covered the foot; depending on the type of shoe, there was also a piece of leather or other material supporting the foot on the back side. However, a shoe was made up of many other elements; for example, the leather trimmings with which certain parts of the shoe were reinforced; the counters that stiffened the heel; the velts, leather straps that were sewn between the sole and the vamp; the barreta, a strip of sheepskin padding that was placed inside the shoe to reinforce the seams and the toe of the shoe to avoid hurting the toes; the insole, a piece of leather that was placed over the sole, inside the shoe, to soften the surface on which the foot rested; and the linings that covered the inner part of the shoe.

Sewing the various parts of the shoe together was a two-step task. The first stage consisted in sewing the different parts of the shoe together; next, the parts were sewn to the sole. To do so, shoemakers used awls, an indispensable tool to pierce the leather in order to sew the shoes with a specific, strong and resistant thread, which was spun on a spindle and waxed. Once the shoe had been pierced, the thread was waxed, placed in the trough and hand pulled to hold the different parts of the shoe together. The wax made the thread slide better, preserving it longer and providing greater adherence to the leather. Once the sole was sewn it was trimmed with a knife and finished, which usually consisted of placing strips of leather around the whole sole to protect the shoe from friction with the ground. These tools were used by both shoemakers who made new shoes and those who mended shoes. As previously mentioned, the latter only mended shoes as they were deteriorating, wearing out and tearing. These garments were not accessible to all, and new shoes were expensive. Thus, shoes were intensively reused and could be repeatedly mended throughout their useful life.

Shoemakers worked sitting on wooden benches or on wide benches with lids, like chests, where they generally kept tools and consumables. They also had hangers on which they hung the finished shoes, displaying them in their shops for consumption by the population (

Figure 3).

3.1. Archaeological Contexts

3.1.1. Angra D (ANGD)

As mentioned before, the vessel referred to as ANGD puts on view the context of a Hispanic shipwreck, which occurred in the Angra do Heroísmo bay, in the Azores, with an archaeological chronology and cultural context dated to the beginning of the 17th century (

Figure 4) [

21]. The archaeological intervention conducted in 1998 revealed the context of a very well-preserved ship. The preserved section of the hull measured almost 29 m in length by a maximum of nine metres in width [

21] (p. 125). Deposited at a depth of eight metres and less than 20 m from the coastline, the Angra D wreck was covered with the ship’s own ballast stones and a thick layer of sediment and silt. The recovered assemblage, as well as the ship’s architectural features, indicate a Hispanic context. Specifically, the recovered ceramics included several fragments of botijas (water jugs), Andalusian majolica and tinajas (large storage jars) produced in the south of the Peninsula and the presence of mercury, are clearly indicative of a possible Hispanic origin for this context [

11], [

21] (p. 573). Mercury, used exclusively by the Castilians in the extraction of silver from the Potosi mines in Mexico, served as an important index fossil for the unequivocal definition of the origin and dating of this shipwreck to the first quarter of the 17th century [

12] (pp. 211–232), [

21] (p. 573).

Although the site is located at a shallow depth, only eight metres, and is regularly battered by storms, this has not prevented the context from remaining sealed and stable [

22]. The thick depositional layer of sediment combined with the ballast favoured the preservation of the remains, namely the preservation of organic material due to the prevailing anaerobic conditions [

23]. This explains the good condition not only of the structural components of the ship, but also of a vast assemblage of materials—wood, leather, vegetable fibres and foodstuffs—mostly related to life on board [

24,

25]. This was the recovery context of numerous leather remains, most of them related to footwear [

11,

12].

In the ANGD footwear assemblage only the soles were preserved, as the remaining components of each piece of shoes were completely disintegrated. The issue of slow sedimentation and the context of an accident, which originated the wreckage, can be one of the factors for the disintegration of the shoes, along with the action of natural agents such as storms and waves that regularly interfere with stability of the site. The absence of some components has hindered the interpretation of typologies, especially because there are not many Iberian references for comparison. However, from what we were able to ascertain, taking into account the comparisons with other contemporaneous European examples, we were able to identify mainly soles of possible gaiters and low boots. A total of 60 leather items were recovered, 17 of which were identified as shoe soles and four as heels (

Table 1). The other items correspond to different shoe components that still need to be identified. Although some of the different components that are associated with shoes are generically recognizable, the different footwear components that were out of context still need further study. According to the shipwreck studies that defined a chronology for the site, these soles provide a typological reference for an Iberian context from the beginning of the 17th century.

One of the important aspects is that some soles show use and patch marks, attesting to their intensive reuse and a possible pathology of the feet (

Figure 5). Another example indicates a thinner and tapered shoe; five layers of leather from the same shoe were preserved. They could belong to a female shoe, possibly indicating the position of a high heel. Four heels with wooden tacks inside were also identified (

Table 1).

3.1.2. Santa Clara-a-Velha (Poor Clares) Monastery, Coimbra (SCV)

The second context concerns the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Velha in Coimbra. This important monastery, located on the left bank of the Mondego River, constitutes an important testimony to the life of seclusion of a Poor Clares community, hierarchically organized just like the secular society (

Figure 6). Built between 1316 and 1330, it was occupied until 1677.

The female convents of the modern period replicated some topoi of life shared with the society in which they were integrated, hierarchically organised and expressing the privileges and duties attributed to each of the social groups. As a matter of fact, convents housed the royal and noble daughters who had not been able or willing to marry and therefore needed a status consistent with their lineage. These ladies rarely entered cloistered life alone, taking with them a more or less numerous retinues of ladies-in-waiting, maids and slaves who recreated within the conventual walls the courtly atmosphere in which their ladies had been born and brought up. Thus, beyond the immutable rituals and hierarchies perpetuating a certain social order, wealthier nuns—who were not always wealthy in terms of dowry, but only in social status and lineage—entered the convent with objects and trousseau that belonged to them, including dresses, shoes and fashionable accessories. Often transformed and reused, for example as paraments or to dress images of the Christ Child, many of these artefacts survived the passage of time and were used until they were worn out or buried in the nuns’ tombs, extending their life as archaeological objects and collectors’ items [

26,

27].

Since almost the beginning of its construction, the proximity of the Mondego River and the site’s low elevation, permeable by the water table, resulted in the whole complex being vulnerable to river flooding. Initially, floods were cyclical but soon became constant due to the rapid siltation process of Mondego River.

Throughout the 15th century, floods in the monastic area became very frequent, silting up the building and compromising health conditions, resulting in the increase of diseases. The Poor Clare’s struggle against water became insufficient to guarantee the safety of the monastery community that faced constant calamities caused by the rise of water levels. To put an end to such a tortuous battle, in 1647 King John IV ordered the construction of a new monastery in a higher area of the city of Coimbra. The nearly three hundred years of continuous use of this secluded elite community provided a testimony of female everyday life, especially material culture for personal use. Furthermore, successive floods originated layers of artefact deposition, which were preserved under water and in muddy areas [

27]. These adverse conditions, in coeval terms, led to constant adjustment, raising the occupation levels, and thus creating successive layers of deposition, which were ideal for the preservation of evidence of monastic daily life until today.

Muddy environments are ideal for the conservation of organic material such as wood, fibres, fruits, seeds, insects and their larvae, parasite eggs, animal and human remains, skin and soft tissues. The anaerobic environment of muddy ecosystems reduces the biological oxidation that causes the destruction of organic components. The impermeability of the mud or ooze thus inhibits the influx of oxygen, slowing down the degradation process of organic materials [

28,

29].

The characteristics of both this monastic community and the preservation conditions of its archaeological materials deposit, along with the fact that several excavation reports were available to the scientific community, led to the decision of contacting the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Velha Museum, nowadays preserved as a national heritage site. The DRESS project team had access to the assemblage of pieces of leather and shoes recovered during the archaeological excavations conducted at the monastery between 1995 and 2001, aimed at minimizing the impact of dredging, and at the rehabilitation of the convent ruins to house a museum, thus giving this space a new life as well as visitors.

Even though few footwear remains were preserved during the post-excavation stage, we realized that many more pieces of leather were probably recovered during the intervention. The lack of conditions for the preventive treatment and conditioning of organic materials in Portugal, at the time of the intervention, meant that many of the items did not survive. Following analysis, the surviving assemblage totalled twenty-three leather elements linked to shoe production. We identified three complete soles, fifteen fragmented soles, one thin heel, four cork soles, two cork base chopines and a leather chopine cover. From this assemblage, we would highlight the thin profiles and the reduced size of the soles, especially those made of cork. One of the soles also has use and patch marks, indicating its intense use. The dimensions of some soles also indicate reduced sizes, which may be connected to young novices entering the convent.

We would also highlight the presence of chopines, which are not common finds in archaeological contexts, as they are only preserved in damp or waterlogged environments. As already mentioned, chopines are a highly significant element of the Early Modern Portuguese footwear characterization, and they were used as both a symbol of social rank and to prevent damaging shoes on the dirt streets. The chopine was in fact a shoe that was tied to a sort of platform made from different materials, often cork or wood, which lifted it several centimetres off the ground.

3.1.3. Campo das Cebolas (Old Market), Lisbon (CCLX)

The Campo das Cebolas is a space located in a relevant axis of the city’s riverside. Hence, it preserved the remains of an intense daily activity over the centuries. This was a walking area connecting the river to the city, where several landfills were made over time to gain space on the riverfront and to consolidate the riverbanks (

Figure 7).

The archaeological intervention was conducted between 2016 and 2017 and aimed at minimizing the impact of the construction of an underground car park. In this context, and for more than a year, all the sediment removal works were monitored by a large team of technicians, including archaeologists specialising in different areas. The intense human occupation of this entire riverside area of the city of Lisbon, once a central axis of the city, as evidenced by both historical and iconographic sources, foresaw the presence of many remains of the most different life experiences, including remains of nautical contexts, given the proximity of the aquatic context of the Tagus River. Indeed, the intervention revealed a wealth of archaeological remains dating from Roman period to 20th century. Many artefacts were recovered, namely ceramics, but also a large number of organic materials that were preserved in a humid environment, such as wood, wicker or leather objects. The extensive archaeological intervention at Campo das Cebolas (Old Market) also reached zones of the former interface area between river and city limits, including landfills and riverbank consolidation zones, where remains of port structures and nautical contexts have been identified. These remains of vessels were fully excavated and dismantled piece by piece to be subsequently removed and kept in tanks filled with water, to be inventoried and studied afterwards.

During the excavation, numerous leather remains were recovered from the different layers of mud in this area. The study and report of this intervention is still ongoing. However, judging from the first analyses of the numerous leather, cork and wood shoe components recovered, and their comparison with contemporaneous footwear, we are convinced that this important site can provide information for the elaboration of essential typologies for the study of Portuguese footwear between the 16th and 17th centuries. A total of more than 311 leather pieces associated with shoe soles, 104 cork soles and 14 complete shoes were identified. The study of these elements is still ongoing, but we would highlight some forms such as low shoes and mules, never mentioned in Iberian archaeological presentations.

4. Materials and Methods

This study on footwear in Portuguese/Iberian context started from the assemblage recovered from the ANGD site. As there is no historical data that may indicate the chronology and identification of the ship, the whole study of this site was based on the information provided by the archaeological remains. If some artefacts seemed to indicate with some certainty that we were dealing with a Hispanic context from the beginning of the 16th century, e.g., the ceramics, other items raised many questions due to the lack of parallels, as happened with the leather materials. During the process of searching for parallels for the shoe soles forms found in ANGD, we realized that there was a gap regarding studies on footwear in southern Europe in the 16th–17th century. Given the lack of parallels, we chose to use the studies conducted in Northern Europe, namely the references from the Netherlands and England, where this problematic is more developed, thus using the typologies defined in these contexts [

30,

31]. Different typologies of footwear found in archaeological excavations were analysed for the first time in a context of Portuguese/Iberian origin. Through the chronological references provided by the ANGD index fossils, such as ceramics or ship features [

21,

32], it was possible to start a reference collection that could be compared with others from equivalent contexts and periods. Each identified leather element was sorted. Those that were in better condition and better able to clarify the questions we wanted to answer were recorded, and drawn, taking into account the issues pertaining to form, function and uses. Additionally, considering which social groups they would be intended and bearing in mind the presumable social universe of a ship circulating between Europe and Americas in the early 17th century. In this context, the historical and social referent of life on board for this period guided some of the questions regarding the footwear remains. We chose to apply a rigorous method for recording the size of soles, forms, wear, and construction methods that allowed us to understand typologies of the footwear existing on board. Following a methodology already presented by Goubitz [

31,

33], all soles and leather fragments were recorded individually, at 1:1 scale, by tracing on acetate sheet as can be seen in

Figure 8. In each piece or set, a colour coding system was created to highlight information such as sewing marks (in blue), wear marks, pressure marks (in brown), fractures or cracks (in green or brown), among other aspects deemed relevant. The same methodology was subsequently applied to the other two contexts also analysed herein, SCV and CCLX (See

Table 1).

Applying the same recording methodology enabled a comparative analysis of the three collections, contrasting the two intertidal contexts, a conventual and an urban one, with the ANGD shipwreck context. The choice of these two contexts was made taking into account, firstly, the chronology of the sites, between 16th and 17th centuries, and secondly, the availability of the materials whose study was deemed relevant in the scope of the DRESS project, e.g., footwear. The fact that these leather items were associated to coherent contexts, with well-defined chronologies, made it possible to analyse the whole set, focusing not only on its forms but also on its possible uses. The depositional conditions of Santa-Clara-a-Velha and Campo as Cebolas, in humid or waterlogged environments, were essential for the preservation of large quantities of organic materials, including leather. Among all the fragments of leather and soles recovered from the different sites, the soles selected for this study were those that were whole or had enough integrity to determine the shape of both the toe and the heel. A few soles that retained manufacture or use/wear marks or had exceptional forms were also selected, such as some heels, cork soles and chopines. In other words, items that might help characterizing the universe of footwear in Portugal and in the Iberian context. The artefacts belonging to these three assemblages were subsequently compared, in terms of their different shapes and sizes, leading to the elaboration of a first typological and chronological proposal for Modern Age footwear in Portuguese and Iberian contexts.

5. Results

The analysis of the forms selected from Angra D for this study showed that out of the 16 identified items only four were complete and had a higher level of integrity. Items ANGD/98-582; ANGD/98-708 (1 and 2); ANGD/98-197.11 and ANGD/98-708 (see Tipology 2), with round toes, tapering in the central area and with rounded heels, may belong to clogs or mules, according to the comparison with Northern European typologies [

31] (pp. 80–81), as can be seen in

Figure 9.

On the other hand, the fragmented soles of items ANGD/98-798.1, ANGD/98-342 and ANGD/98-S.R. show wide rounded toes, indicative of possible boot or ankle boot forms, resembling forms recovered from the San Juan, a 16th century shipwreck found at Red Bay, in the Coast of Labrador (Canada) [

30] (pp. 113–117).

Amongst the Angra D assemblage, item ANGD/98-187.3 was deemed particularly relevant, since it differs from other pieces due to its tapering or pointed toe, which may correspond to a borzeguim (buskin) or pontilha. This form, as well as ANGD/98-342, show use marks, including two wear tears. The wear mark on ANGD/98-187.3 indicates a tear caused by repeated flexion of the foot, while the wear of ANGD/98-342 indicates greater load on the big toe area, one of the parts of the shoe that is subjected to greater pressure.

All the broad heels found at Angra D show features consistent with shoes or clogs, being made of several layers of leather, between six and nine layers, attached by stitching with thread and wooden tacks in the central part. The ANGD/98-582 form is the most complete piece of footwear, with five layers of leather still intact and in situ, including the inner sole, which was in contact with the foot. The leather was thin and well cared for, indicating a delicate shoe, given the tapering of the piece in the heel area, which raises the possibility of corresponding to a female heeled shoe.

The Santa Clara-a-Velha assemblage had few complete forms, and only three soles were selected, CSV-E11, SCV-T76 and SCV-T74, very similar to each other in shape and size (see Typology 3,

Appendix A). The slightly tapered toe and wide central part indicate a possible closed shoe. The complete leather forms show marks of heavy wear and abrasion, which can be indicative of extensive use. The sole recorded as SCV-T95 is incomplete, only the central part was preserved. However, it is one of the most tapered forms in this context, closer to the ANGD forms, and may correspond to a clog. The presence of a thin heel (see

Figure 10) with a height of some 2.5 cm, composed of four layers of leather and structured in the centre by a single wooden tack, was also deemed relevant. Parallels for this form can be found in other 17th century northern European forms, namely from the Dordrecht excavations [

31] (p. 90), as can be seen in

Figure 11.

The other forms of footwear that were complete and preserved at Santa Clara-a-Velha correspond to cork soles or chopines. Two of them, SCV-T28 and SCV-T28.1, were identified as being soles of thin, tapered shoes. The analysis of their structure revealed no evidence of how they would be attached to the other components of the shoe. The conservation and restoration treatment to which they were subjected hindered the observation of such details, since these pieces were impregnated with PEG. This resin stabilises the cork, preventing it from disintegrating and oxidising, but at the same time the pieces become shiny, which prevents observation of details [

28] that might facilitate the interpretation of the way in which the object was manufactured. Items SCV-T36.3, SCV-T36.1, SCV-T36.2 and SCV-T36.4 are parts of chopines. Chopines were made of several overlying cork layers, attached by means of resins and leather threads. The various overlaid layers were then lined with leather or cloth and served to protect the footwear from the dirt of the streets, by raising the feet above ground level. In the case of the Santa Clara-a-Velha (Poor Clares) Monastery assemblage, the parts of the preserved chopines still showed traces of the holes used for passing the leather threads required for overlaying different cork layers.

We would highlight SCV-T77, a totally unique piece in Portuguese context, which corresponds to a leather chopine cover. The oval shaped piece was used to cover the cork layers of the chopine, protecting it from wear and softening the contact with the shoe (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

This unique item features a thin central layer, which sustained the pressure of the body’s weight, and, around it, a portion of thicker leather, which covered the sides of the chopine. This piece was not totally intact, showing wear in the area pressed by the foot, with pieces of leather missing both on the front and on the back, in the areas where more pressure was applied while walking (

Figure 13).

Regarding the Campo das Cebolas (Old Market) assemblage, the post-excavation inventory work is still in progress and only a few recorded items are available. However, some forms were selected which, due to their composition and typology, seemed important for this study as they were found in stratigraphic units securely dated to the 16th century and because they are related to the other forms under analysis, namely the chopines. These elements were recovered from the riverside area of the city of Lisbon, where successive landfilling has been carried out since medieval times, to gain living space along the banks of the Tagus River. This nearby area, which connected the port area of the Santarém Wharf to the Rua Nova dos Mercadores Street, was one of the busiest streets of the city.

Items CCLX16_SAP002 and CCLX16_SAP010 correspond to two types of mules and were almost complete (see Typology 3,

Appendix A). In the case of CCLX16_SAP002, this mule form with the highest degree of integrity allowed us to fully understand how the sole and the upper part covering the foot were attached. The sole has a wide, square-shaped toe, which was fragmented at the toe, and a thin heel, as shown in

Figure 14.

The upper part still preserved the folding areas that were attached to the base, and it was possible to observe the connection between the lower and the upper parts. CCLX16_SAP010 (see

Figure 15) was a little more fragmented than CCLX16_SAP002. However, it differs from the former due to a small decorative fringe on the upper part. This fringe is quite worn, and the sole is incomplete, missing part of the heel. This is a slightly more tapered form at the heel, in relation to CCLX16_SAP002, as can be seen by comparing

Figure 14 and

Figure 15.

These two examples of mules are entirely unique in archaeological context, but parallels for this typology can be found in 16th century Portuguese iconography, as can be seen on a 1541 painting, shown in

Figure 16. The precise date of this painting and the fact that its author was a court painter of King Manuel I (r. 1495–1521) also allow us to securely contextualise the use of this type of shoe at the Portuguese court during the first half of the 16th century.

Four pieces related to chopines from the Campo das Cebolas (Old Market) assemblage were also selected for this study. Numerous cork artefacts were recovered during the archaeological intervention, many of which corresponded to chopines or parts of chopines. Although during the excavation they were not immediately recognized as elements related to footwear, crossing data with the DRESS project enabled the identification of the chopines. These items are not yet fully accounted for, but the selected pieces, due to their integrity, show some interesting details of their construction, namely the presence of leather or fabric covers that wrapped the shoes. The study of the chopines also revealed the way in which the layers were overlaid in order to reach the desired height of the chopine. Item CCLX_SAO006.1 still had two layers of cork in situ, and some of the leather threads used to attach the two parts have also been preserved. We do not know whether this piece is complete or not. However, considering that it would be necessary to place the foot at the highest possible level to keep it away from the dirtiness of streets and tracks, we would hypothesise that it had more layers, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Item CCLX16_SAP009 (see

Figure 17) belongs to a patten or galosh and is yet another of the unpublished footwear remains identified in a Portuguese archaeological context.

As a piece of footwear, it had the same function as the chopine, i.e., to elevate the feet above ground level. However, this piece, which is concave in the centre, does not rest completely on the ground, and features only two points of contact. The foot was fastened by one or two straps which would pass around the toe and instep, thus tying the foot to the shoe. European parallels indicate that pattens were used since the medieval period and into the Early Modern Age. In Northern Europe they are mostly made of wood, as illustrated in

Figure 18. The use of cork is a specific characteristic of the Portuguese and Iberian context, where this raw material is abundant.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In the scope of this preliminary study on Portuguese footwear, which can be extrapolated to the broader Early Modern Age Iberian context, we would start by pointing out that the Iberian scenario proved to be substantially different from Northern Europe, where the study of footwear is a well-established research area, particularly in Scandinavia, the Netherlands and England [

20,

29,

31,

34]. Thus, the latter served as a methodological basis for our approach to the subject.

Although the archaeological context originally identified as being able to contribute to our research in the scope of the DRESS project was a ship, several similarities and equivalences were found between the different Iberian forms of footwear identified in other terrestrial contexts in intertidal areas. As previously mentioned, the context of research and historical reconstruction of the process of creating the garments of a Portuguese infanta in the early 16th century led to the development of a strategy to mitigate the absence of written and visual information provided by coeval sources. The fact of having assembled a multidisciplinary team, with archaeologists who had excavated at different sites, enabled diversifying the knowledge and contributing to the advancement of the state of the art of several subjects related to the history and cultures of clothing, namely the accessories and particularly footwear, the subject of this paper. Both the rigorous recording of the pieces found at Angra D and consequent awareness of the importance of these remains for the construction of a narrative on material culture used in daily life by the Early Modern communities in Portugal contributed to broadening the research possibilities of the DRESS project. This was combined with the search for assemblages with similar remains and, in this sense, the collaboration of other entities, such as scientific coordinators of the archaeological intervention conducted at Campo das Cebolas (Old Market) (Cláudia Manso, Catarina Garcia and Brígida Baptista) and the directors and conservators of the Santa Clara-a-Velha (Poor Clares) Monastery.

Besides the possibility of accessing the data and artefacts recovered in the excavations, the DRESS project team took into consideration the need to address archaeological sites featuring similar conditions, chronologies and contexts, in order to foster a comparative methodology. Hence, three different archaeological contexts linked to daily life were chosen, all in submerged or intertidal zones.

Despite some vicissitudes associated with this type of study—artefact conservation conditions, selection, and disposal of remains, reports and results still in progress—the archaeological results presented herein contribute to a remarkable advance in the state of the art regarding the typologies, materials and footwear techniques present in the Iberian Peninsula. The studied archaeological contexts surpass Portuguese environments, and the DRESS holistic approach reached for historic and visual contextualization of different cultural spheres, namely through the comparison with North European contemporaneous footwear examples. Indeed, Northern European studies were highly relevant as a methodological basis for our own study, particularly in terms of the recording and analysis methods applied to footwear remains. Still, and even though the data compiled and analysed are consistent and support the identification of different types of mules, boots, pattens and chopines, in comparative terms we can hardly go much further. Actually, comparison with Northern European typologies, particularly Scandinavian models, has shown that the situation within the Iberian empires is substantially different. See, for example, the case of chopines—local materials like cork, combined with leather, were the most widely used raw materials, as opposed to the wood and leather used in Northern Europe.

We would emphasize the presence of rounded shapes in the soles and the evidence of recurrent use of clogs, present in all the analysed cases, attesting to the permanence and widespread use of this type of footwear. Usually made of cheap and resistant materials, providing durability and some degree of comfort, which may be associated with the most demanding professions, e.g., seamen. The marks observed on two of the ANGD soles are indicative of the high degree of wear and tear of footwear in this period, typically very worn and subjected to harsh conditions, such as those that caused this shipwreck. Although no remains of chopines have been unequivocally identified in ANGD, the shape of item ANGD/98-582 supports the hypothesis that it most probably corresponds to a type of footwear of higher quality and finesse, which could be somehow related to a woman’s foot. In this case it is possible to observe the construction of the sole, consisting of at least five layers, reinforced at the heel. The tapering of the heel indicates the likelihood of a high heel. Some explanations for the absence of chopines in ANGD may be related to the fact that cork components may not have survived a shipwreck. In this context, footwear remains can also provide information about the composition of the crew—which hardly included women—but, above all, about the function of the ship, probably not a passenger carrier, or, if there were any female passengers, they would not be the kind of persons who wore chopines.

Regarding the forms identified in the Santa Clara-a-Velha (Poor Clares) Monastery assemblage, they are not particularly diverse or complex. However, it is worth mentioning the identification of a heel fragment (SCV-T95;

Figure 10). This can be explained either by the choices made in terms of materials disposal over years of consecutive excavations or by the absence of other elements besides the soles, which hinders a more detailed characterisation. Since SCV is the most homogeneous and coherent case study, namely because it is exclusively female, the recovered forms attest above all to a certain uniformity of the coeval usages. Indeed, the conventual universe reproduced the hierarchy and social relations of secular life on a smaller scale. Most of the community were nuns of humble origins and from social strata at the bottom of the pyramid, servants and slaves, whose life and death were anonymous, their belongings even being reused by the community. Nuns from the royalty, nobility or wealthier groups who could provide a quality trousseau representative of 16th- and 17th century elite garments were, therefore, fewer. Moreover, the very nature of these objects, made of sumptuous and delicate materials, favoured their degradation over time. Finally, the successive floods to which the monastery was subjected until it was abandoned in 1677, and even afterwards, led to an almost irreparable destruction of the tombs of the most relevant abbesses, buried in decorated stone boxes inside the church. Hence, so far it has not been possible to recover any remains of clothing or footwear that might have existed there.

However, the uniformity of the identified sole sizes along with the biological characterisation of the burials of this community [

27] are data that, jointly analysed, will allow us to reach more conclusions about the footwear and the ways in which it was used by women of the Early Modern period. Actually, all identified shoe and cork soles measure between 15 and 17 centimetres (see

Table 1), and we know from the palaeobiological data that the average height of these women would be 150 centimetres, which may provide a consistent working basis for the characterisation and development of size matching tables.

This paper also highlights the prevalence of chopines in an archaeological context, as suggested by the written sources, which is totally unprecedented in this type of studies. As already identified in SCV, we would also highlight the persistent remains of chopines and chopine pattens in CCLX, which provides further information on the remains of leather strips used to assemble the layers of cork. The presence of chopines in these two contexts reveals a certain equivalence of these items, both in terms of dimension, form and type of manufacture. The chopines from both SCV and CCLX display a structure of several layers of cork attached with thin leather twine. Although these pieces have only two layers, we believe that more layers of cork could be added to obtain more height, being subsequently covered with leather or fabric as observed in SCV-T77 (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

Despite the unprecedented wealth of archaeological remains recovered and analysed, related to the production of different sole forms, several doubts still persist, concerning the typological nature of these finds, since the remaining footwear components were not identified. The latter would have provided specific information about the final form of each type of shoe, how they were made, what materials were used, and certainly about which social groups wore them. Thus, and despite the consistency of the compiled data, there are still some gaps concerning forms and construction methods. Nevertheless, by presenting the state of the art this study may contribute to the disclosure of new or existing contexts in Southern Europe and the Mediterranean basin. To sum up, this text and the tables presented herein are a first exercise of analysis and systematization of the knowledge pertaining to the type of footwear preserved in Early Modern Iberian archaeological contexts. As such, we also aim at being able to raise awareness of these artefacts’ importance, often neglected, and to broaden its impact by creating bridges to Iberian imperial contexts and laying out items for comparison with other data from the European territory.