Investigating Colors and Techniques on the Wall Paintings of the ‘Tomb of the Philosophers’, an Early Hellenistic Macedonian Monumental Cist Tomb in Pella (Macedonia, Greece)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

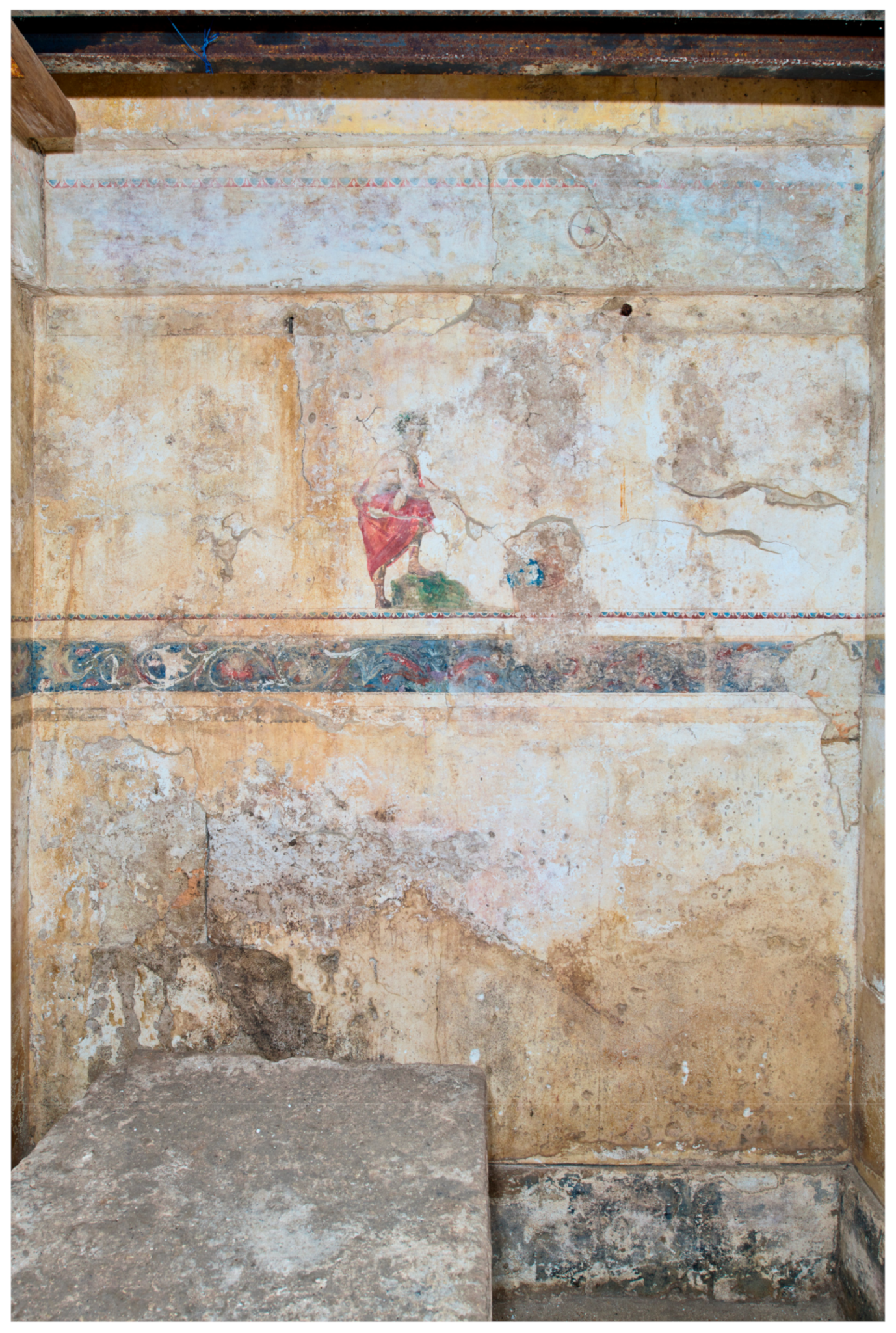

2.1. The Tomb and Its Painted Decoration

- The toichobate. This is the lowest part of the wall, which was painted dark blue (0.30–0.35 m high);

- Off-white, unpainted plaster band. 1.00–1.06 m high;

- Two tainiae. Two narrow bands, one light brown (0.035–0.038 m high) and one off-white (0.036 m high);

- A kosmophoros. This is a frieze (0.135–0.15 m high) that is decorated with elaborate floral patterns on a blue background. The decorative scheme of this frieze includes scrolls, acanthus leaves and lilies, smaller flowers and perhaps anemones;

- Tainia. This narrow off-white band is 0.04–0.043 m high;

- Egg-and-dart painted Ionian molding, approximately 0.018 m high;

- Main figural frieze. This is the highest of the decorated sections, measuring 0.75–0.82 m, where figures of philosophers are represented (two figures on the south wall, two on the north, one on the east and one standing figure on the west wall; see below for more details of the figures);

- Recessed socket. Unpainted, approximately 0.09–0.10 m high; it would have perhaps supported a wooden lining;

- Figural frieze. About 0.32 m in height, this protruding section shows riders on galloping horses, rosettes and, according to the original publication, stelai with palmette crownings. Each stele appears to be on top or behind a mound. The background of the frieze is light blue;

- Egg-and-dart painted Ionian molding. As the previous one, this was approximately 0.018 m high;

- Conclusive elements. A painted tainia in light yellow, 0.30 m high. Painted mutules and guttae are found on the north and south sides, between the beam sockets and along the upper edge of the uncut sections of the blocks.

State of Preservation of the Main Figural Scenes

2.2. Scientific Methodology

2.2.1. High-Resolution Digital Photography and Broadband Imaging

2.2.2. Handheld X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

2.2.3. Cross-Sections

2.2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy Coupled with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Microanalyzer (SEM-EDAX)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preliminary Stages

3.2. The Painter’s Colorful ‘Palette’ (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5)

| Location | Elements | Tentative Identification | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Plaster | Ca, Fe, Cu, Sr, Pb, Ba? | Calcium carbonate | |

| (b) Hand, flesh tone | Ca, Ti, V, Fe, Cu, Sr, Pb | Vanadinite, lead-based white, Egyptian blue | High concentration of Pb, suggesting the use of a lead-based white. Egyptian blue also shows high IR luminescence. |

| (c) Green leaf over yellow | Ca, V, Fe, Cu, Sr, Ba, Pb | Malachite, vanadinite, Egyptian blue | V may relate to vanadinite in the yellow underlayer (see location e). Cu may relate to both Egyptian blue (see also VIL images) and, especially, a Cu-containing mineral, such as malachite. |

| (d) Red lips | Ca, V, Fe, Cu, Sr, Ba, Pb | Red ochre, lead-based white, vanadinite | As the main paint layer appears to be missing from this area, the red pigment may correspond to a colored underdrawing/preparation. |

| (e) Yellow temple/yellow leaf | Ca, V, Fe, Cu, Sr, Ba, Pb | Vanadinite, lead-based white, Egyptian blue | V, Cu and Pb are elements already found in the skin tones, probably in the form of vanadinite, a Pb-based white and Egyptian blue (see also VIL images). The yellow paint layer may be related to the leaves of the wreath, rather than the skin tones (see location c). The presence of litharge could not be excluded or confirmed. |

| (f) Dark brown mantle | Ca, Ti, V, Fe, Cu, Sr, Pb | Yellow/brown ochre, lead-based white | This layer contains considerable amounts of Fe, suggesting the use of ochres, possibly applied with a Pb-based white and a darker pigment (perhaps carbon, given the strong absorption in the IR-reflected image). |

| (g) Yellow mantle | Ca, Ti, V, Fe, Cu, Sr, Pb | Yellow/brown ochre, vanadinite, lead-based white | This layer contains considerable amounts of Fe, suggesting the use of ochres, possibly applied with a Pb-based white and vanadinite. The presence of litharge could not be excluded or confirmed. |

| (h) Black Hair | Ca, Ti, V, Fe, Cu, Sr, Ba, Pb | Carbon-based black, lead-based white | No distinctive elements aided the identification of the black pigment. The strong absorbance in the IR-reflected image may point to the presence of a carbon-based black. |

| Location | Elements | Tentative Identification | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| (i) Blue | S, Ca, Ti, Fe, Cu, Sr, Pb | Egyptian blue | The presence of S is unclear. Possible explanations include the use of gypsum or indicative of sulphation, which is a likely explanation. |

| (j) Purple | S, Ca, Ti, V, Mn, Fe, Cu, Sr, Pb | Unknown colorant likely of organic origin, with Egyptian blue and lead-based white | No traces of Br were detected. |

| (k) Yellow | S, Ca, Ti, V, Fe, Cu, Sr, Pb | Vanadinite, lead-based white | |

| (l) Orange | S, Ca, Ti, V, Fe, Cu, As, Sr, Pb | Arsenic-based orange, ochres, lead-based white | Options include mimetite, orpiment, realgar, pararealgar. |

| (m) Red | S, Ca, Fe, Cu, Sr, Zr, Ba, Hg, Pb | Cinnabar, lead-based white | |

| (n) Green | S, Ca, Ti, V, Mn, Fe, Cu, Zn, As, Sr, Zr, Pb | Conichalcite | The presence of Zn may be related to adelite minerals. |

| (o) Black | S, Ca, V, Mn, Fe, Cu, Sr, Ba, Pb | No distinctive elements aided the identification of the black pigment. Possibly a carbon-based black, based on the strong absorption in the IR-reflected images. |

| Location | Elements | Tentative Identification | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| (p) Green | K, Ca, V, Mn, Fe, Cu, Sr, Ba, Pb | Copper-based green, lead-based white | This spectrum is similar to (c) |

| Location | Elements | Tentative Identification | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| (q) Purple | S, Ca, Fe, Br, Sr, Ba, Pb | Brominated compound | Likely mainly 6,6′-dibromoindigo |

| Samples | Top Surface Color/ Location | Stratigraphy of Paint Layers from Top to Bottom | Elements | Suggested Pigments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P.1 Figure 18a | Light brown/coarse grained plaster layer | Ca, Si, Al | Calcium carbonate, clay | |

| P.2 Figure 18b | Light yellow/band from the upper zone | Semi-transparent yellow layer with orange grains | Si, Ca, Fe, K, Al, Cl, Ti | Yellow ochre |

| P.3 Figure 18c | Yellow/rolled-up papyrus from the north wall | Yellow layer with black particles | Ca, Fe, Pb, Si | Yellow ochre mixed with lead white and carbon black (?) (inferred from strong absorption in the IR range) |

| P.4 Figure 18d | Bright red/himation of the male figure, west wall | Red layer | S, Hg, Ca, Si | Cinnabar |

| P.5 Figure 18e | Bright red/flower from the scroll frieze, north wall | 1. Red-orange layer 2. Black layer | 1. S, Hg, Ca, Si 2. Si, Ca, Al | 1. Cinnabar 2. Carbon black (inferred from strong absorption in the IR range) |

| P.6 Figure 18f | Bright red/egg-and- dart Ionian molding, south wall, upper part | Red-orange layer | S, Hg, Ca, Si | Cinnabar |

| P.7 Figure 18g | Red/Egg-and- dart Ionian molding, south wall, lower part | Red layer | Fe, Ca, Si, Al | Iron oxides (hematite) |

| P.8 Figure 18h | Orange-brown/flower from the scroll frieze, north wall | 1. Yellow-orange layer 2. Black layer 3. Blue particles | 1. Ca, Fe, Al, Si 2. Si, Ca 3. Cu, Ca, Si | 1. Hematite/goethite 2. Carbon black (inferred from strong absorption in the IR range) 3. Egyptian blue |

| P.9 Figure 18i | Brown/garment of the figure (left), north wall | Yellow layer with orange particles | Ca, Fe, Si, Al | Iron oxides (hematite, goethite) |

| P.10 Figure 18j | Brown/garment of the figure (right), south wall | Yellow layer with black particles | Ca, Fe, Si, Al, Pb | Iron oxides (goethite) mixed with carbon black (inferred from strong absorption in the IR range) |

| P.11 Figure 18k | Blue/egg-and-dart Ionian molding, south wall, lower part | Light blue layer | Cu, Ca, Si | Egyptian blue |

| P.12 Figure 18l | Blue/background of the frieze with the horse race, south wall | Blue, semi-transparent layer | Cu, Ca, Si, Al, Fe | Egyptian blue |

| P.13 Figure 18m | Blue/Egg-and- dart Ionian molding, south wall, upper part | Blue layer | Si, Ca, Cu | Egyptian blue |

| P.14 Figure 18n | Green/flower from the scroll frieze, north wall | 1. Green layer with yellow particles 2. Traces of a thin black layer | 1. Cu, As, Ca, Si, Al, Fe 2. Si, Ca, Cu, C | 1. Conichalcite 2. Carbon black (inferred from strong absorption in the IR range) |

| P.15 Figure 18o | White/flower from the scroll frieze, west wall | Opaque white layer | Pb, Na, Al, Ca | Lead white |

| P.16 Figure 18p | Blue/background from the scroll frieze, west wall | 1. Blue particles in a semi-transparent white matrix 2. Traces of a thin black layer | 1. Cu, Ca, Si 2. Si, Ca, Cu, C | 1. Egyptian blue 2. Carbon black (inferred from strong absorption in the IR range) |

| P.17 Figure 18q | Purple/flower from the scroll frieze, west wall | Dark purple-black layer | Ca, Na, Mg, Si, P, Pb | Organic colorant |

3.3. Color and Painting Technique

3.3.1. The Frieze with the Horse Race

3.3.2. The Scroll Frieze’s (Kosmophoros) Polychromy

3.3.3. Cast Shadows and Skin Tones on the Figures of the Main Frieze

3.4. New Iconographical Evidence Revealed through Imaging

3.4.1. The Frieze with the Horse Race

3.4.2. The Figure of the Man on the West Wall

3.4.3. The Figures of the North Wall

3.4.4. The Figure of the Man on the East Wall

3.4.5. The Two Figures of Men on the South Wall

3.4.6. The Rocky Landscape

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brecoulaki, H. La Peinture Funéraire de Macédoine. Emplois et Fonctions de la Couleur, IVe-IIe Siècle av. J.-C.; Centre de Recherches de l’Antiquité Grecque et Romaine, Fondation Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique: Athens, Greece, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kakoulli, I. Greek Painting Techniques; Archetype: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S. Hellenistic Painting in the Eastern Mediterranean, Mid-Fourth to Mid-First Century B.C. In The Cambridge History of Painting in the Classical World; Pollitt, J.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 170–237. [Google Scholar]

- Scheibler, I. Die Malerei der Antike und Ihre Farben; Jonas Verlag: Weimar, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Plantzos, D. The Art of Painting in Ancient Greece; Kapon Editions: Athens, Greece, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rhomiopoulou, K.; Schmidt-Dounas, B. Das Palmettengrab in Lefkadia, Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, 21. Beiheft; Verlag Philipp von Zabern: Mainz am Rheim, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andronikos, M. Vergina. The Royal Tombs; Ekdotiki Athinon: Athens, Greece, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Andronikos, M. Βεργίνα ΙΙ. «O τάφος της Περσεφόνης»; The Archaeological Society at Athens: Athens, Greece, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tsimbidou-Avloniti, M. Μακεδονικοί τάφοι στον Φοίνικα και στον Άγιο Aθανάσιο Θεσσαλονίκης; Archaeological Resources Fund: Athens, Greece, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lilimbaki-Akamati, M. Κιβωτιόσχημος τάφος με ζωγραφική διακόσμηση από την Πέλλα, Πέλλης 1; Ministry of Culture, 17th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brecoulaki, H. Greek Painters. Colours and Materials. In The Painters of Pompeii. Roman Frescoes from the National Archaeological Museum of Naples; Grimaldi, M., Ed.; Electa: Napoli, Italy, 2022; pp. 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Brecoulaki, H. Greek Painting and the Challenge of Mimesis. In A Companion to Ancient Aesthetics; Destrée, P., Murrey, P., Eds.; Wiley: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 218–236. [Google Scholar]

- Lilimpaki-Akamati, M. Νέος κιβωτιόσχημος τάφος με ζωγραφική διακόσμηση στην Πέλλα; AEMTh 15; Auth Press: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2001; pp. 451–460. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, Y.; Sakellari, H.; Kavousanaki, D.; Minos, N. Φυσικοχημικός χαρακτηρισμός χρωστικών από του κιβωτιόσχημο τάφο της Πέλλας. In Κιβωτιόσχημος τάφος με ζωγραφική διακόσμηση από την Πέλλα, Πέλλης 1; Lilimbaki-Akamati, M., Ed.; Ministry of Culture, 17th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2007; pp. 138–175. [Google Scholar]

- Triantafyllou, S. Κιβωτιόσχημος τάφος Πέλλας με ζωγραφική διακόσμηση. Τα αποτελέσματα της οστεολογικής εξέτασης. In Κιβωτιόσχημος τάφος με ζωγραφική διακόσμηση από την Πέλλα, Πέλλης 1; Lilimbaki-Akamati, M., Ed.; Ministry of Culture, 17th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2007; pp. 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, D. Aratus Phaenomena. Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries 34; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Minos, N.H. συντήρηση των τοιχογραφιών του τάφου. In Κιβωτιόσχημος τάφος με ζωγραφική διακόσμηση από την Πέλλα, Πέλλης 1; Lilimbaki-Akamati, M., Ed.; Ministry of Culture, 17th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2007; pp. 134–136. [Google Scholar]

- Verri, G. The spatially resolved characterisation of Egyptian blue, Han blue and Han purple by photo-induced luminescence digital imaging. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 394, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verri, G.; Saunders, D. Xenon flash for reflectance and luminescence (multispectral) imaging in cultural heritage applications. Br. Mus. Tech. Bull. 2014, 8, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Saatsoglou-Paliadeli, C.h. Compendiaria. In La pittura parietale in Macedonia e Magna Grecia; Pontrandolfo, A., Ed.; Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi in ricordo di Mario Napoli, Salerno-Paestum, 21–23 novembre 1996; Università degli Studi di Salerno, Dipartimento di Beni Culturali, Pandemos: Salerno, Italy, 2002; pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Brecoulaki, H.; Perdikatsis, V. Ancient Painting on Macedonian Funerary Monuments, IV-III c.B.C.: A Comparative Study on the Use of colour. In Colour in Ancient Greece. The Role of Colour in Ancient Greek Art and Architecture (700-31 B.C.), Thessaloniki, Greece, 12–16 April 2000; Tiverios, M.A., Tsiafakis, D.S., Eds.; Aristotelean University Press: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2002; pp. 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Brecoulaki, H. Precious colours in Ancient Greek polychromy and painting: Material aspects and symbolic values. Rev. Archéologique 2014, 1, 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Skovmøller, A.; Brøns, C.; Sargent, M.L. Egyptian Blue: Modern Myths, Ancient Realities. J. Rom. Archaeol. 2016, 29, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostomitsopoulou Marketou, A.; Andriulo, F.; Steindal, C.; Handberg, S. Egyptian Blue Pellets from the First Century BCE Workshop of Kos (Greece): Microanalytical Investigation by Optical Microscopy, Scanning Electron Microscopy-X-ray Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy and Micro-Raman Spectroscopy. Minerals 2020, 10, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecoulaki, H.; Verri, G.; Guimier-Sorbets, A.-M.; Avlonitou, L. Eclectic uses of Egyptian blue in Greek painting: A versatile painting material. In Archaeology of Colour. Technical Art History Studies in Greek and Roman Painting and Polychromy; Brecoulaki, H., Ed.; in preparation.

- Eastaugh, N.; Walsh, V.; Chaplin, T.; Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium: A Dictionary of Historical Pigments; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 105–106. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, J.; FitzHugh, E.W. Pigments Based on Carbon. In Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Volume 4; Berrie, B.H., Ed.; National Gallery of Art: Washington, DC, USA; Archetype Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gliozzo, E.; Ionescu, C. Pigments—Lead-based whites, reds, yellows and oranges and their alteration phases. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2022, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, B.; Jockey, P.h. Le marbre, l’or et la couleur. Nouveaux regards sur la polychromie de la sculpture hellénistique de Délos”. In Peinture et Couleur dans le Monde Grec Antique; Descamps-Lequime, S., Ed.; Musée du Louvre: Paris, France, 2004; pp. 163–191. [Google Scholar]

- Karydas, A.; Brecoulaki, H.; Bourgeois, B.; Jockey, P. In situ X-ray fluorescence analysis of raw pigments and traces of polychromy on Hellenistic sculpture at the archaeological museum of Delos. Bull. De Corresp. Hellénique 2009, 51, 811–829. [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard, B.; Rodler, A.; Bredal-Jørgensen, J.; Klein, S.; Brøns, C. A Highly Unusual Constituent in Roman Polychromy; Goldsmith: Paris, France, 2017; Session 12a, Book of Abstracts; p. 2320. [Google Scholar]

- Nord, A.G.; Tronner, K.; Björling Olausson, K. Copper vanadate minerals found in mediaeval mural paintings. Stud. Conserv. 2012, 57, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, W.N.; Frost, R.L.; Williams, P.A. Molecular structure of the adelite group of minerals: A Raman spectroscopic study. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2003, 34, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buisson, N.; Burlot, D.; Eristov, H.; Eveno, M.; Sarkis, N. The Tomb of the Three Brothers in Palmyra: The Use of Mimetite. Archaeometry 2015, 57, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brøns, C.; Stenger, J.; Bredal-Jørgensen, J.; Di Gianvincenzo, F.; Brandt, L.Ø. Palmyrene Polychromy: Investigations of Funerary Portraits from Palmyra in the Collections of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Heritage 2022, 5, 1199–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broers, F.T.H.; Janssens, K.; Nelson Weker, J.; Webb, S.M.; Mehta, A.; Meirer, F.; Keune, K. Two Pathways for the Degradation of Orpiment Pigment (As2S3) Found in Paintings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 8847–8859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanmeert, F.; De Keyser, N.; van Loon, A.; Klaassen, L.; Noble, P.; Janssens, K. Transmission and reflection mode macroscopic X-ray powder diffraction imaging for the non-invasive visualization of paint degradation in still life paintings by Jan Davidsz. de Heem. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 7153–7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, B.J.; Frost, R.L.; Martens, W.N. Characterization of conichalcite by SEM, FTIR, Raman and electronic reflectance spectroscopy. Miner. Mag. 2005, 69, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brecoulaki, H.; Sotiropoulou, S.; Katsifas, C.; Karydas, A.G.; Kantarelou, V. A microcosm of colour and shine. The polychromy of chryselephantine couches from ancient Macedonia. Technè. Sci. Serv. L’histoire L’art Préservation Biens Cult. 2014, 40, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jambor, J.L.; Owens, D.R.; Dutrizac, J.E. Solid solution in the adelite group of arsenates. Can. Mineral. 1980, 18, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Brecoulaki, H. Sur la technè de la peinture grecque ancienne d’après les monuments funéraires de Macédoine. Bull. De Corresp. Hellénique 2000, 124, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurizio, A.; Arrais, A.; Marsano, F.; Agostino, A.; Fenoglio, G.; Idone, A.; Gulmini, M. A diagnostic study on folium and orchil dyes with non-invasive and micro-destructive methods. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 142, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Verri, G.; Bourgeois, B.; Yannick, V.; Jeammet, V.; Pérez-Arantegui, J.; Degano, I.; Carò, F. (Forthcoming). Purple for the δῆμος: Art and Luxury in Greek Coroplastic Polychromy of the 4th-3rd century BCE. In Color & Space. Interfaces of Ancient Architecture and Sculpture. Proceedings of the 10th Round Table on Polychromy in Ancient Sculpture and Architecture; 2020; in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Aceto, M. Pigments—The palette of organic colourants in wall paintings. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2021, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronti, L.; Felici, A.C.; Ménager, M.; Vieillescazes, C.; Piacentini, M. Spectral Behaviour of White Pigment Mixtures Using Reflectance, Ultraviolet-Fluorescence Spectroscopy, and Multispectral Imaging. Appl. Spectrosc. 2017, 71, 2616–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalaitzi, M. Figured Tombstones from Macedonia, Fifth—First Century BC; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Dounas, B. Macedonian Grave Tumuli. In Tumulus as Sema. Space, Politics, Culture and Religion in the First Millenium BC; Olivier Henry, O., Kelp, U., Eds.; Topoi, Berlin Studies of the Ancient World, 27; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 101–142. [Google Scholar]

- Rouveret, A. Histoire et Imaginaire de la Peinture Ancienne (Ve siècle av. J.-C.-Ier siècle ap. J.-C); École Française de Rome: Rome, Italy, 1989; pp. 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Petsas, P.h. O τάφος των Λευκαδίων; The Archaeological Society at Athens: Athens, Greece, 1967; pp. 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, V.J. Hellenistic Painting Techniques: The Evidence of The Delos Fragments; E.J. Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1985; pp. 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rouveret, A.; Walter, P. Peintures Grecques Antiques; Fayard/Musée du Louvre: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Abramitis, D.H.; Abbe, M.B. A Group of Painted Funerary Monuments from Hellenistic Alexandria in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Technè 2019, 48, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzi, M.; Stamatopoulou, Μ. Bookrolls and Writing Tablets as Pictorial Gear: Images of Literati on Macedonian and Thessalian Tombstones of the Classical and Hellenistic Periods. In Ancient Macedonia VIII; Pappas, V., Terzopoulou, D., Eds.; Institute for Balkan Studies: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2021; pp. 539–585. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J. The Material Culture of Greek Astronomy. JHA 1999, 30, 237–286. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, S. The Genesis of Hipparchus’ Celestial Globe. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2018, 18, 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. Elusive Stones: Reading Posidippus’ Lithika Through Technical Writing on Stones. In Labored in Papyrus Leaves: Perspectives on an Epigram Collection Attributed to Posidippus (P.Mil.Vogl. VIII 309); Hellenic Studies Series 2; Acosta-Hughes, B., Kosmetatou, E., Baumach, M., Eds.; Center for Hellenic Studies: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brecoulaki, H.; Verri, G.; Kalaitzi, M.; Maniatis, Y.; Lilimpaki-Akamati, M. Investigating Colors and Techniques on the Wall Paintings of the ‘Tomb of the Philosophers’, an Early Hellenistic Macedonian Monumental Cist Tomb in Pella (Macedonia, Greece). Heritage 2023, 6, 5619-5647. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6080296

Brecoulaki H, Verri G, Kalaitzi M, Maniatis Y, Lilimpaki-Akamati M. Investigating Colors and Techniques on the Wall Paintings of the ‘Tomb of the Philosophers’, an Early Hellenistic Macedonian Monumental Cist Tomb in Pella (Macedonia, Greece). Heritage. 2023; 6(8):5619-5647. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6080296

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrecoulaki, Hariclia, Giovanni Verri, Myrina Kalaitzi, Yannis Maniatis, and Maria Lilimpaki-Akamati. 2023. "Investigating Colors and Techniques on the Wall Paintings of the ‘Tomb of the Philosophers’, an Early Hellenistic Macedonian Monumental Cist Tomb in Pella (Macedonia, Greece)" Heritage 6, no. 8: 5619-5647. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6080296

APA StyleBrecoulaki, H., Verri, G., Kalaitzi, M., Maniatis, Y., & Lilimpaki-Akamati, M. (2023). Investigating Colors and Techniques on the Wall Paintings of the ‘Tomb of the Philosophers’, an Early Hellenistic Macedonian Monumental Cist Tomb in Pella (Macedonia, Greece). Heritage, 6(8), 5619-5647. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6080296