Abstract

Radical left culture and heritage—understood as incarnations of leftist artefacts and praxis both past and present—have taken risks in challenging hegemonic machinations often when it is unpopular to do so. To the ire of hegemons, leftist projects across the globe have marshalled places, spaces, and technologies into sites of empowerment and struggle utilising ‘small’ and ‘big’ acts of resistance and critical interventions to champion social justice—sometimes successfully, and at other times, less so. However, the preservation of projects’ artefacts, praxis, and memory work has been anything but straightforward, owing primarily to institutional politics and infrastructural and resourcing issues. Taking The Freedom Archives (FA) as a case study, this article explores how FA is preserving the distinctive political education programme that underpinned the iconic liberation struggle in Guinea-Bissau that kickstarted the seismic, global decolonisation project in the late 1950s. The article argues that FA could substantially enhance the preservation and memorialisation of that programme in the Metaverse—if this materialises as a fully open, interoperable, and highly immersive space (1) unfettered by hegemonic regulation, and (2) characterised by ‘strategic witnessing’, ‘radical recordkeeping’, and user agency. In doing so, FA would serve as an exemplar for leftist projects globally.

1. Introduction

This article conceptualises radical left culture and heritage1 as expressions and embodiments of ways of being, doing, feeling, imagining, knowing, living, seeing, thinking, working, and interacting with others that are in some shape or form impelled by a social justice ethos that may or may not have its roots in the past [1,2,3,4]. This culture and heritage are manifest in tangible, intangible, and digital forms that range from artefacts to sites of encounter and production to the adherence to customs, knowledges, motivations, principles, skills, traditions, and values that are conserved, preserved, and passed on from generation to generation of leftists to maintain a sense of identity and continuity [5,6,7]. However, the preservation and memorialisation of that sense of identity and continuity, and by extension related artefacts and praxis, have been anything but straightforward. A viable and sustainable solution to addressing this circumstance, this article posits, is the Metaverse in its fully developed form—if the latter’s current vision as a widely accessible, open, immersive, and interoperable environment as presented later on in this article is realised. In putting this overarching argument forward—and wherever appropriate—the article cross-references and signposts key arguments and recurring ideas and concepts by pinpointing relevant sections, subsections, and endnotes throughout in an effort to help readers connect analysis and discussion as accessibly and effectively as possible.

In making its case, the article proceeds as follows. It discusses the methodological approach underpinning analysis and discussion in Section 2. At the heart of that approach is the combination of (1) previous ethnographic fieldwork, (2) a meta-analysis of key academic literature and industry expert commentary on and around the opportunities and challenges associated with the Metaverse, and (3) the study of documentary evidence—including archival research. The Freedom Archives (FA) (https://freedomarchives.org/, accessed on 7 March 2018), which is taken as the case study in this article, is briefly introduced—and the justification for its selection provided. Section 3 discusses how varied leftist cultural interventions and traditions have been framed over time and across the globe—highlighting some of the most central features that have been said to characterise those interventions and traditions. In doing so, carefully selected examples of an artistic (literary, performative, and visual), journalistic, activist, and authorial nature are described at length for illustration. Taken together, the examples are significant because they not only reflect the sheer breadth and variety of leftist cultural traditions and rich praxis but are also bound by the same core recurring theme of challenging hegemony and associated injustice, exploitation, and oppression, albeit drawing on numerous means, instruments, and tools.

Although radical left cultural and heritage projects have undertaken many efficacious and varied interventions—both in the past and present—Section 4 picks up some of the greatest challenges that have stymied the capability of many projects to preserve their artefacts, critical praxis, and associated memory adequately. Crucially, preservation is unpicked to provide a nuanced understanding that captures what is termed as ‘passively stored memory’ and ‘actively circulated memory’—drawing on seminal work at the intersection of the canon, archive, cultural memory, performance, and identity by Aleida Assmann, Jan Assmann, and Diana Taylor. The two terms—‘passively stored memory’ (the archive) and ‘actively circulated memory’ (the canon)—are picked up in Section 5 and operationalised in the analysis of how FA circumvents institutional politics as well as infrastructural and resourcing challenges. Discussion here brings into focus how FA utilises ‘strategic witnessing’ and ‘radical recordkeeping’ to reclaim control of, and reaffirm the power to, expression of leftist hi(stories), influence, memory, narratives, and representations. Particular emphasis is placed on the unique political education programme that underpinned the widely acclaimed revolutionary movement in Guinea-Bissau that paved the way for the deconstruction of colonialism in Africa and around the world. The key architects of that programme were (1) Amílcar Cabral, and (2) the liberation movement party he founded under the name of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC).

Where FA’s digital archive currently preserves ‘passively stored memory’ of PAIGC’s political education programme in 2-D formats that are static and sterile and as such, do not allow for artefacts to be animated in ways that enhance users’ capabilities to absorb, process, and understand key historical information effectively, Section 6 discusses the distinctive architecture and rich possibilities that existing Metaverse-type environments presently offer, highlighting key opportunities and challenges. This also includes an exploration of what the fully developed Metaverse could offer—if its vision as a readily accessible, empowering, highly immersive, resilient, trustworthy, low-maintenance, sustainable, and interoperable environment materialises. Section 7 explores how FA could leverage key ‘metaversal’ opportunities to considerably elevate its memorialisation work of PAIGC’s learning curricular (including both the protagonists featured therein and those absent) through use of 3-D immersive experiences. Such use—which I call ‘metaversal memorialisation’—would clearly not be limited to FA and leftist cultural projects. Far from it, it would lend itself well to utilisation by any individuals, social formations, entities, and organisations engaged in heritage work widely considered—whose ultimate goal is to keep the past operational in the present. Although there is a high likelihood that many of the serious problems afflicting the mobile Internet could very well be carried over into the development and use of the fully developed Metaverse, this article concludes on a cautiously optimistic note in Section 8. That note positions the Metaverse as an environment that is capable of reconfiguring engagement with FA’s preservation and memory work in novel, creative, empathic, personalised and communal, inclusive, and immersive ways. In turn, this would effectively and meaningfully memorialise connections between the past and present in the continuing struggle for social justice, thereby rendering FA a desirable model for leftist projects across the globe.

2. Multi-Pronged Methodological Approach, and Data Analysis

Analysis and discussion in this article are underpinned by the application of a set of interrelated methods comprising (1) previous ethnographic fieldwork conducted by the author, (2) meta-analysis, and (3) the study of documents and artefacts—including archival research. Previous ethnographic fieldwork has involved my immersion as a participant observer in the organisational settings and technological spaces of radical left projects over extended periods of time—dating from 2010 to this day. This has enabled (1) first-hand observation of behaviours, critical interventions, practices, and traditions of leftist settings across various countries, (2) conduct of in-depth semi-structured qualitative interviews to understand behaviours and norms—including associated beliefs, motivations, principles, and values (a) not amenable to observation, and (b) needing clarification, (3) examination of artefacts and documents in various formats about, and relevant to, the leftist settings under study, and (4) production of comprehensive, written accounts of my analysis of overall activity in leftist settings selected as case studies [8,9,10,11]. Ethnographic data was complemented by a meta-analysis that summarised and compared (1) working definitions, (2) current features, and (3) touted opportunities and challenges associated with the development and prospective use of the Metaverse. The greatest strength of this technique is that it allowed me to generate thorough reviews of literature and industry expert opinion supplied in a wide range of new academic outputs as well as authoritative and rich non-academic secondary sources in unobtrusive fashion [10,12].

Accessing much of the latest insights currently unavailable widely was further facilitated by the study of documentary evidence which enabled me to cross-reference different (and sometimes conflicting) perspectives on (1) the trajectories of leftist cultural preservation, and (2) the promise of the Metaverse in considerably transforming various areas of human activity. Archival research allowed for the exploration of varied holdings of numerous leftist archives—with a particular focus on The Freedom Archives (FA) taken as the case study in this article. FA is a pioneering, educational, leftist archive based in the US that has prolifically documented and disseminated the social justice work undertaken by numerous national and international progressive movements during the countercultural era2 [13] and beyond. FA was carefully selected as the case study because of its (1) subscription to leftist conventions and praxis since its inception in the mid-to-late 1990s—although its founders have subscribed to left-wing ideology and values since the 1960s as appendages of the countercultural movement, (2) strong and long track record of preserving varied leftist artefacts and culture in a variety of formats, and (3) global influence and reach in terms of iteratively informing and shaping ‘strategic witnessing’ and ‘radical recordkeeping’ as key elements of leftist critical and empowering praxis.

Crucially, this methodological approach supported the triangulation of data effectively and helped put them in wider perspective. The approach also considered key issues relating to authenticity, credibility, reflexivity, and meaning during the processes of data collection and data analysis [14]. An inductive approach to the analysis of (1) interview and observational data generated from previous ethnographic fieldwork, (2) meta-analysis review data, and (3) the study of documentary evidence—including archival research was employed. That approach was helpfully informed by grounded theory [15] which I utilised to (1) pull out and categorise key information and themes, (2) make connections among them, (3) pinpoint recurrent connections, (4) make sense of them, and (5) offer explanations through (a) formulating arguments, and (b) building analysis and discussion throughout this article.

3. Conceptualising Radical Left Culture and Heritage

This section theorises expressions, embodiments, and incarnations of artefacts, critical praxis, and traditions that have characterised generations of individual leftists, projects, and the diverse constituencies they have advocated for and served. It provides a selection of mostly artistic (literary, performative, and visual), journalistic, activist, and authorial examples to illustrate the operationalisation of leftist beliefs, ideas, motivations, and principles over time and across different geographies.

3.1. ‘Say[ing] the Unsayable, Suggest[ing] the Unsuggestable, Do[ing] the Undoable’

In the early 1900s, the Russian performing artist and clown—Vladimir Leonidowitch Durov—steadily built a reputation in Europe for mocking powerful elites for their indifference to the numerous social and economic ills that afflicted many ordinary people. In 1907 while performing in Germany governed by Emperor Wilhelm II, Durov satirised Wilhelm II in a subtle and skilfully improvised manner—according to a third-person account described by Joel Schechter [16] (p. 2). Durov placed a cap worn by German police officers at the time in the circus ring. Referring to the cap as ‘Helm’ meaning ‘helmet’ in English, he prompted his trained pig to retrieve it. Making use of the technique of ventriloquism3, Durov then conditioned the pig to appear to be saying ‘Ich will Helm’ translated into English as ‘I want the helmet’. But this phrase can also be translated as ‘I am Wilhelm’. The audience applauded because they understood the phrase to be a pun equating Emperor Wilhelm II to a pig. Likewise, the German police officers in attendance understood the pun but did not take kindly to it which resulted in Durov’s unfortunate arrest and prosecution. His pig was fortunate to escape prosecution. If it had not been for that third-person account, this incident might never have been documented.

Fast forward to the peak of national resistance against European colonial rule in Africa during the 1950s. When discussing the national liberation of African colonies from European powers, the name Amílcar Cabral is very rarely mentioned in public discourses—if at all. Yet, according to Peter Karibe Mendy, Amílcar Cabral has been profiled by the New York Times ‘as “one of the most prominent leaders of the African struggle against white supremacy”’ and by ‘The Times of London […] as “one of the most extraordinary leaders and thinkers of modern Africa”’ [17] (n.p). Mendy notes further that ‘[i]n February 2020, Cabral was voted second greatest leader of all time (after Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Sikh Empire) by more than 5000 readers of the BBC World Histories Magazine, which commissioned historians to compile a list of 20 great leaders in world history’ [17] (n.p). To put this in perspective, Winston Churchill (British Prime Minister between 1940 and 1945, and then again between 1951 and 1955) and Abraham Lincoln (US President between 1861 and 1865) were voted third and fourth greatest leaders of all time respectively4. For a person of such international stature, it is baffling why Amílcar Cabral and his key achievements (including as an influential author and writer) are not much more widely known—and commemorated and celebrated accordingly.

Born in Guinea-Bissau (formerly Portuguese Guinea), educated in Portugal as an agronomist, and working in that role as a Portuguese colonial government employee on return to his native country, Amílcar Cabral is said to have been preoccupied with developing political theories and adopting strategies for combating fascist ideology and liberating Guinea-Bissau (and by extension the whole of Africa) from colonial rule. Charles Peterson narrates that after Cabral founded the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), he and his associates engaged in thoughtfully planned and carefully executed political resistance to colonial rule over years [18] (n.p). Resistance initially took the form of workers’ strikes that advocated for better wages and improved working and living conditions. However, vicious and sustained Portuguese reprisal and repression gradually escalated PAIGC’s resistance into full-scale, guerrilla-style military warfare that sought nothing less than national independence. Sadly, Amílcar Cabral’s fight against colonial repression led to his assassination in early 1973 at the hands of Portuguese machinations. On the bright side, national independence was secured not long after. Cabral’s tireless efforts and call to action from the mid-1950s onwards inspired other African countries to liberate themselves from colonial rule. His legacy inspires many in Africa and beyond to confront ‘injustice, deprivation, exploitation, and oppression’ and to express ‘solidarity “with every just cause”’ [17] (n.p). Had Amílcar Cabral not been a prolific writer, valuable accounts of his critical political interventions that set in motion a seismic, historical, and political change project that spanned the globe, would very likely not have seen the light of day.

Around the time Amílcar Cabral was plotting to topple colonial rule in Africa during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Art Kunkin—a pioneering underground journalist, a mover and shaker of the countercultural movement in the US, and founder of the prominent Los Angeles Free Press newspaper (LAFP)—was extremely critical of the actions of state authorities and other elites. According to Bruce Fessier, Art Kunkin and LAFP enjoyed the reputation of being ‘the best, most professionally[-run] underground weekly’ in the US that ‘help[ed] build opposition to the Vietnam War by publicising the times and places of anti-war protests’ and ‘touched [protestors and other readers] like Instagram and Twitter [now X]’ touch their users today [19] (n.p). Art Kunkin’s advocacy and satirical journalism mocked and outraged state authorities to the point that LAFP reporters were denied press passes to cover key criminal and political events. This coincided with a time when state authorities had been implicated in a range of criminal activities and unsavoury political dealings [1]. In writing elsewhere [8] (p. 369), I have narrated how—out of utter frustration—Art Kunkin then published a news article with the headline ‘There Should Be No Secret Police’ in which the names, phone numbers, and addresses of eighty narcotics police officers in California were listed. State authorities prosecuted Art Kunkin and LAFP which resulted in the paper’s bankruptcy. This subsequently distracted attention from the wrongdoings of state authorities that had been spiralling out of control and which the paper had reported on in the kind of breadth and depth that established papers shied away from [1]. Had other countercultural activists, social movement scholars, and Art Kunkin’s family not told this story, there would likely be no record of it today.

Leap forward to 2014. Following the forceful annexation of Crimea, Russia was criticised internationally for breaching Ukraine’s national sovereignty. Opposition to the annexation grew both from within Ukraine and outside [20]. One Crimean native by the name of Oleh Sentsov—a progressive filmmaker and well-known anti-fascist activist—was very critical of, and overly vocal about, Russia’s excessive brutal repression and unjust occupation. While most people understandably fled Crimea, he chose to stay to engage in peaceful protest activity. According to a scholarly account by Zakhar Popovych [21] (n.p), Oleh Sentsov came together with ‘Crimean democratic socialists and anarchists from the Student Action union’ as well as other activists to protest Russian occupation. Although Sentsov did not utilise film for his activist work in this particular instance, he became a symbol for the struggle against Russian imperialism. Sentsov called for justice for all political prisoners in Russia and mocked Russian foreign politics which led to his arrest and subsequent prosecution for conspiracy to commit terrorism [22]. Tom Grater narrates that Oleh Sentsov was ‘sentenced to 20 years for “terrorism acts”’—charges that Amnesty International described as ‘fabricated’—and while incarcerated, went ‘on a hunger strike that lasted 145 days, leaving many believing he would never make it out alive’ [23] (n.p). Miraculously, he did, was released in September 2019, and has since resumed making progressive films. If Sentsov’s story had not been told and retold by witnesses, fellow activists, sympathetic journalists, and family members, it would probably never have been documented. Perhaps Sentsov would not even be alive today. If anyone thought that Oleh Sentsov’s experience of brutal detention in Russia was going to deter him from taking part in efforts to repulse the most recent Russian invasion of Ukraine that started on 24 February 2022, they were mistaken. According to Jay Nordlinger [24] (n.p) who interviewed Sentsov recently, Sentsov is doing ‘what conscience has compelled him to do’ which is to continue engaging in ‘activism’ and ‘soldiery’ in defence of his country.

Wind back to 2016. Los Angeles-based artist Illma Gore made headlines when her painting featuring the then-presumptive nominee of the Republican Party in the US—Donald Trump with a small penis—went viral on social media and the Internet. In the Guardian Newspaper, Gore [25] (n.p) explained that the painting was intended among other things ‘to evoke an emotion’ and ‘to raise questions about how we think about gender’. For instance, if an influential figure like Donald Trump is painted ‘with a massive penis’, does this signal his powerfulness—imagined or real? And does a small penis equate to effeminacy? If the answer is yes, ‘what is wrong with effeminacy to begin with?’—Illma Gore asked. Predictably, Trump and his supporters were outraged. Illma Gore was subjected to online abuse, assault, and serious threats of legal action, grievous bodily harm, and even death. Facebook and other dominant digital platforms banned her work. Amidst intense adversity, Gore [25] (n.p) defended her artistic freedom by ‘reach[ing] out to galleries in the hope of exhibiting [her painting]’ but ‘US galleries were scared to show it—scared of going up against Trump, scared of receiving the same threats [she] did’. A breakthrough was achieved when Maddox Gallery in London put the painting on display. The painting, however, remains inaccessible on some major digital platforms to this day.

These forms of producing, practising, and shaping culture represent a very small selection of innumerable examples of artistic, journalistic, activist, and authorial projects across the globe that I conceptualise as ‘radical’ in the sense commonly associated with left-wing political ideology and related values. With the exception of Amílcar Cabral and Art Kunkin, I am not sure Vladimir Leonidowitch Durov, Oleh Sentsov, and Illma Gore would perceive themselves as being ‘radical’—let alone identify as ‘leftist cultural producers or practitioners’. But I argue that their critical interventions are indeed ‘radical’ projects in the leftist tradition in their very different ways. They are ‘radical’ in the sense that they advocate ‘social reform [and champion] independence of or departure from what is usual or traditional’ [2] (p. 1), albeit to varying degrees. To borrow Sharon Lockyer’s [26] (p. 767) words, projects that produce, practise, and shape culture in a radical, left-wing way generally:

say the unsayable, suggest the unsuggestable, do the undoable and express thoughts and desires that are normally suppressed in serious [hegemonic] discourse. [Such projects] facilitate the transgression of social norms and mores, allow the [producer or practitioner] to engage in risk taking and to push at the boundaries of acceptability.

By equating Emperor Wilhelm II to a pig, Vladimir Leonidowitch Durov clearly did ‘the undoable’ during a time period when the authority of powerful actors in society was neither questioned nor subject to mockery—at least publicly. Likewise, Amílcar Cabral did ‘the undoable’ by internationally defying colonial oppression—thereby making himself the arch-enemy of the Portuguese colonial government and some of its allied European colonial superpowers. In a similar vein, Art Kunkin did ‘the undoable’ when his LAFP divulged the names, phone numbers, and addresses of eighty Californian police officers. Oleh Sentsov suggested ‘the unsuggestable’ by referring to the Russian occupation of Crimea as an act of ‘cowardice’ and publicly calling the pro-Russian government administering the peninsula ‘criminals’ [22] (n.p). Illma Gore’s Trump painting attracted controversy with the intention of stimulating debate and discussion about perceptions of gender and power in society—implications of which are often publicly unspoken but nonetheless thought of, and experienced first-hand, by many on a regular basis. In their different ways, then, these projects took risks and prodded at the boundaries of what is deemed acceptable by established hierarchies.

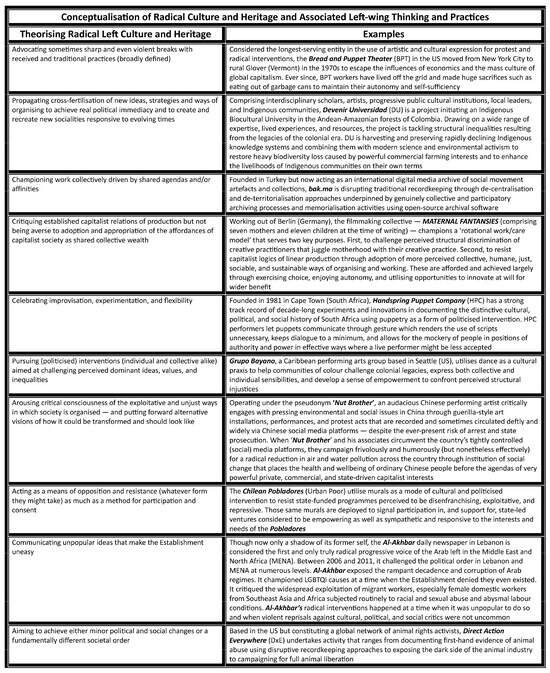

Projects that produce, practise, and shape culture in radical left ways—many of which involve the making of the arts (literary, performing, and visual), lifestyles, experiences, film, news, digital content, and other ephemera often spanning diverse periods, locations, and topics—have a long and rich tradition of making critical interventions in the cultural, economic, social, and political circumstances of the day [8,27,28,29,30,31]. For Lisa Tessman [32] (p. 4), such critical interventions focus on transforming systems of exploitation, oppression, and subjugation through fighting against established formalities, hierarchies, and hegemons of different kinds that put social justice out of reach for many people. The range of projects listed in Figure 1 below captures the conceptualisation of interventions impelled by radical culture and heritage and associated left-wing thinking and practices.

Figure 1.

The theorisation and examples of radical left culture and heritage presented here have been collated and synthesised by the author from the following works: [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

3.2. Small and Big Acts of Resistance as Critical Interventions in the Leftist Cultural Tradition

Here, it is worth discussing acts, projects, and struggles located on opposite ends of what we could think of as a radical leftist continuum encompassing modes of critical intervention. One end of that continuum accommodates everyday acts and artefacts while revolutionary movement projects and liberation struggles occupy the other end. Some everyday acts and artefacts considered as critical interventions are not necessarily conceived of as ‘radical’ in the sense explained above at the time of undertaking (or making and sharing), but nonetheless end up ‘becom[ing] unexpectedly politicised’ as Chuck Kleinhans puts it [6] (p. 25). An example Kleinhans [6] gives is the vicious beating of Rodney King in 1991 in Los Angeles by police officers. On the thirtieth anniversary of this event in March 2021, Sam Levin retold the story of how ‘[t]here were no smartphones at the time, but [that] a witness filmed the beating from his balcony and gave the footage to a local news station. It was one of the first videos to capture this form of abuse that was so common’ [47] (n.p). Although the video itself did not trigger civil disobedience, riots, and mass protests, the subsequent acquittal of the police officers responsible for Rodney King’s beating did. ‘That is the only way they hear us sometimes’, said a citizen—who experienced the mass protests first-hand—of the local authorities in Los Angeles [47] (n.p). Thirty years on and with the ubiquity of smartphones, everyday recordings of police brutality, abuse, and institutional misconduct remain highly politicised both in the US and in many countries across the globe.

Everyday acts guided by the leftist cultural tradition utilise experimentation and struggle, and sometimes involve risk-taking, in bearing witness to, and questioning, conditions of existence dominated by established hierarchies and formalities in society [5,6,48,49]. Making use of varied and continually evolving aesthetics and styles of production, many leftist projects—including many of those presented in Figure 1 above—have exploited everyday acts as critical interventions. Often, those interventions have been ‘radically’ efficacious in building on progressive, oppositional, countercultural conventions and narratives to challenge and subvert the status quo—sometimes successfully, and at other times, less so. Those interventions have also been adept at proposing alternative, bold, and concrete visions of what perceived, fairer, more widespread, and lasting changes in culture and society might look like [4,7,10,50]. This is reminiscent of what Steve Crawshaw and John Jackson in their widely acclaimed book—Small Acts of Resistance: How a Bit of Courage, Tenacity and Ingenuity Can Change the World—refer to as small and innovative acts of resistance undertaken around the world. Those small acts of resistance typically tend to (1) challenge structural inequalities and associated exploitation and subjugation by hegemons at a micro level, and (2) reimagine how this state of affairs could be transformed to achieve as close to comprehensive and sustained social justice as possible for individuals and the varying social formations of which they are a part [34].

In a similar vein, what I call ‘big’ acts of resistance—as exemplified by revolutionary ventures and liberation struggles—draw on innovation among other things to challenge hegemons, albeit at a macro level. This level encompasses a much broader scope and is typically characterised by much greater intensity than the micro level comprising everyday acts and artefacts. Leftist critical interventions in liberation struggles are manifested through attempts to free people from the tentacles of exploitation, repression, and subjugation [51,52]. The ultimate goal is to attain absolute freedom through (1) dismantling the repressive institutions that overpower the capacity of oppressed people to control their destiny, (2) reclamation of political, economic, cultural, social, environmental, and technological sovereignty, and (3) deployment of a range of tools at different junctures ranging from labour strike action to educational projects to citizen development programmes to cultural resistance to armed struggle [32,53,54]. Amidst the pursuit of these key goals, however, liberation struggles have also involved racialisation, human depravity, extreme suffering, war atrocities, and severe loss of human lives—leaving legacies in places that have been termed ‘difficult heritage’ or ‘dark heritage’5 [55,56,57]. Amílcar Cabral’s seismic, decolonisation project, which we will return to later, offers a useful illustration of how liberation struggles can be efficacious as leftist critical interventions—despite operating in extremely hostile circumstances. Cabral called for the doctrines of ‘return to the source’ and ‘re-Africanisation’ which comprised the pursuit of cultural renewal. That renewal was informed by (1) the readaptation of precolonial African traditions, (2) the embrace of positive contributions from colonial oppressors’ cultures, and (3) the cultivation of democracy, good governance as well as socioeconomic and technological development on the terms of Africans [58] (pp. 424–436).

In doing so, Cabral boldly expressed thoughts and desires that were routinely suppressed during the peak of colonial rule. At the same time, he articulated what impactful and successful acts of resistance undertaken by leftist projects have done across history. Around the climax of European colonial rule in Africa in the early-to-mid 1950s, Amílcar Cabral communicated accessibly how horrible and violent colonial life was—and how much worse it was destined to get. He also conveyed persuasively what a better life would look like outside the confines of colonial domination—and what he saw as the most realistic paths towards colonial destruction [52]. By offering this explanation of, and motivation for, the commitment to overthrow the colonial system of oppression across Africa, Cabral laid the foundation for its demise. It is worth adding that the critical interventions impelled by small and big acts of resistance are characterised by three key common drivers among many other features. First, leftist interventions are driven by anger which helps projects to maintain a hard resolve against the perceived adversary. Second, they exhibit courage which helps projects to take risks, to make sacrifices, and to accept loss. Third, they require loyalty whereby actors within projects demonstrate unequivocal feelings of support for, and allegiance to, the cause(s) of resistance [25,34,54,59,60]. However, whether it is everyday acts and artefacts of defiance at a micro level or big acts of resistance at a macro level, the preservation of corresponding critical interventions and associated cultural traditions and heritage has not been straightforward.

4. ‘Benign Neglect’, Structural Discrimination, Resourcing Issues, and the Politics of Preservation

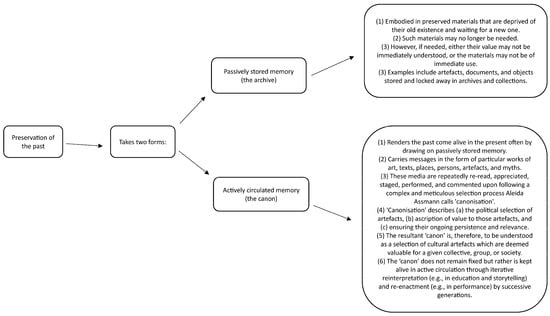

Many projects producing, practising, and shaping culture in the radical left-wing tradition have either had their work preserved inadequately or not preserved altogether. Preservation here is commonly understood to encompass work that is collected and conserved by public cultural organisations such as established museums and archives on the one hand, and on the other, work that is preserved by the projects themselves—if they have the requisite resources at their disposal. Elsewhere, I have drawn on the seminal work by Aleida Assmann, Jan Assmann, and Diana Taylor [61,62,63] at the intersection of the canon, archive, cultural memory, performance, and identity to illuminate a critical and more refined understanding of preservation in a two-fold sense. Preservation can take either a passive or an active form. In its passive form, preservation captures cultural artefacts that are no longer needed because their immediate use is not known and, thus, stored away in archives awaiting possible new use(s). For Aleida Assman, such artefacts embody passively stored memory that can be called upon at a later point [61] (pp. 9–10). In the later sections of this article, I refer to this as passive memorialisation.

In its active form, preservation renders the past come alive in the present—often utilising passively stored memory as base material. Here, information, messages, and symbols embedded in cultural artefacts such as works of art, customs, traditions, texts, and symbolic sites actively circulate memory through repeated appreciation, re-reading, recitation, performance, review, reinterpretation, and re-enactment. To Aleida Assmann, this results from ‘canonisation’—a complex process which involves (1) a political selection of artefacts, (2) ascription of value to those artefacts, and (3) rendering those artefacts continually relevant [61] (p. 9, emphasis in original). In this scenario which I allude to as active memorialisation later on in this article, the ensuing ‘canon’ does not remain fixed but rather is kept alive in active circulation through iterative reinterpretation and re-enactment by successive generations [64]. It is worth noting that canonised artefacts are susceptible to being locked away in archives at some point if not in use in the same way that archived artefacts become base material for the canon when needed [61,65]. Please see Figure 2 below for a graphical (re)presentation of the concepts of passively stored memory (the archive) and actively circulated memory (the canon).

Figure 2.

This diagrammatic (re)presentation of passive stored memory and actively circulated memory has been assembled by the author drawing on the following works: [49,61,62,63,64,65].

More often than not, projects have not been able to conserve and preserve their work as a result of very limited means. In other instances, (1) a lack of time (owing to the pressure to move on swiftly from one intervention to the next) and (2) negative perceptions (seeing some interventions as not having been as efficacious and successful as hoped for) have been the causes for not preserving work [6,66]. Where traditional museums and archives have collected radical left artefacts, projects have had to cede control and contend with dominant representations which have proven problematic [49,65,67,68,69,70]. In other instances, projects have had their resources viewed and treated by dominant institutions as mere ‘collectibles, “salvage” projects, or tools for institutional diversification’ [71] (p. 203) in efforts to boast compliance with equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) agendas and to tout community engagement track records [72]. In yet other instances—particularly in the Global South, leftist collections housed in public cultural institutions have been destroyed during turbulent events. For instance, Sonia Vaz Borges has narrated that the archives holding the vital collections of Amílcar Cabral and his African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) were destroyed and lost during the civil war that engulfed Guinea-Bissau between 1998 and 1999 [51] (p. 19).

It is fair to say that the artefacts of many projects have not been preserved by mainstream museums and archives for two main reasons. First, the tendency of projects to overly criticise, satirise, and taunt dominant hierarchies means the ‘centuries old’, ‘predominantly singular and authoritative’ taxonomic order used by those hegemons to ‘collect, identify, describe and document artefacts’ [72] (pp. 110–111) invariably discriminates against such projects in favour of ‘the important and powerful people [in] society’ [2] (p. 2). For Katherine Jarvie and colleagues, this reflects ‘benign neglect’ that not only fails to recognise and appraise projects engaging with radical left culture as ‘significant’ and worthwhile, but also denies them the opportunity to contribute to ‘societal memory’ [73] (p. 354). Second, the projects’ predominant coverage of arts and cultural activity on the fringes of society, dissident politics, minority concerns, alternative lifestyles, and even revolutionary movements has been perceived to be siloed inside subcultures viewed as peripheral and unimportant [4,74,75,76]. This view is routinely taken by hegemonic structures rooted in ‘an ideology that is fundamentally oppressive in nature’ [2] (p. 3) and ‘privilege[s] the perspective of the status quo’ [73] (p. 357).

For instance, it is not straightforward that the projects introduced earlier by Vladimir Leonidowitch Durov, Amílcar Cabral, Art Kunkin, Oleh Sentsov, and Illma Gore are eligible for preservation as legitimate records of ‘societal memory’—in part due to their fiery and unapologetic attacks on the institutional structures run by the status quo6. In the specific context of the distinctive, global, decolonisation project spearheaded by Amílcar Cabral and PAIGC, Sonia Vaz Borges reports on how the Portuguese National Archives Office maintains a record of Cabral and the PAIGC that is extremely adversarial. Borges recounts that PAIGC’s heritage on record is ‘built with the intention of defending [the] Portuguese colonial government and thus present[ing] an unfavourable picture of PAIGC and [its] achievements’ [51] (p. 19). In a similar vein, Miguel Cardina and Inês Nascimento Rodrigues direct attention to how successive Portuguese governments have appropriated and exploited power relations and moral hierarchies to undermine the goals achieved by Amílcar Cabral and PAIGC through the deployment of antagonistic and prejudiced narratives, myths, and symbologies [53,54].

As briefly mentioned earlier, many projects have not been able to preserve their own work. Some have left their past behind unpreserved [1,10,59]. Others have simply ‘sold out’ and crafted a new identity for themselves in a bid to move with the times [3,66,77,78]. Yet others have simply not had access to adequate infrastructure and associated resources in the form of manpower, technical expertise, and funding to preserve their work on their own terms. In a recently published edited collection titled Radical Film, Art and Digital Media for Societies in Turmoil, for example, Jacob Geuder [79] and John Akomfrah and colleagues [80] draw attention to the infrastructural challenges of preserving radical left culture and heritage—particularly issues of technology, funding, and accessibility—faced by the ‘Mídia Independente Coletiva’ in Brazil and the former Black Audio Film Collective in the UK, respectively. That said, the tide has been steadily turning. In particular, as the cost of (digital) technologies has considerably and continually fallen, so have opportunities opened up for leftist projects to proactively preserve their artefacts in different ways.

5. ‘Strategic Witnessing’, ‘Radical Recordkeeping’, and Complementary Modes of Memorialisation

Emerging discourses and scholarship are reporting on projects that collect, compile, and passively and actively memorialise radical left culture and heritage mostly on their own terms [38,68,72,73]7. Utilising the opportunities and tools afforded by the ubiquity of digital platforms as a result of continually decreasing technology costs, projects are creating, administering, and interpreting their work and wider activist ephemera for much broader publics on an increasingly networked basis as Özge Çelikaslan’s map drawing of archival alliances across the globe effectively demonstrates [38]. In doing so, projects are not only ‘using [passive and active memorialisation] in radical ways’ to render left-wing culture and heritage alive, but also achieving ‘unprecedented reach and immediacy of impact’ through engaging in ‘a form of “strategic witnessing”’ [73] (p. 353). Projects bear witness by asking critical ‘questions of [one-sided, hegemonic] truth[s] and experience[s], presence[s] and absence[s], death[s] and pain, seeing and saying[s], and trustworthiness of perception’ [59] (p. 1034). Projects utilise such ‘witnessing’ to involve individuals, diverse publics, and social movements in the processes of collaboratively documenting and commemorating activist and radical left ephemera across various personal and collective offline and virtual contexts. In turn, those contexts transcend cultural, political, economic, social, geographical, and technological boundaries. In what follows, we look at the concepts of ‘strategic witnessing’, ‘radical recordkeeping’, and memorialisation in action at The Freedom Archives (FA) which is taken as the case study in this article.

5.1. Decolonising and Giving Voice to Marginalised Leftist Pasts at the Freedom Archives (FA)

The Freedom Archives—henceforth abbreviated to FA throughout the rest of this article—is a non-profit educational archive located in San Francisco in the US. Since its inception in the late 1990s, FA has been committed to the preservation and dissemination of historical audio, video, and print materials documenting progressive movements and culture from the 1960s onwards. According to FA’s current co-directors, Nathaniel Moore and Claude Marks [81] (n.p), artefacts spanning ‘anti-colonial struggles […] in-depth interviews and reports on social and cultural issues; activist voices from a number of social justice movements; and original and recorded music, poetry, and sound collages’ have been preserved. These artefacts were produced by a broad range of left-leaning cultural producers and workers who intervened in, and covered, issues and themes ranging from anti-imperialism to human rights to internationalism to liberation struggles. In doing so, those producers and workers gave marginalised groups and movements a voice—one that was typically ‘unheard in, or distorted by, the establishment media’ [81] (n.p). Over the years, FA has continued to restore and catalogue artefacts stored on carrier technologies of different kinds, thereby ‘saving them from further deterioration and loss, and making their historical value and lessons accessible to future generations’ [81] (n.p).

The archival research I conducted revealed that FA preserves its artefacts in a variety of formats including VHS and radio cassette tapes, CD-ROMS, DVDs, still photographs, photo displays, pamphlets, journals, website, blog posts, in-house documentaries, and publications of different kinds. Proceeding this way, according to Moore and Marks, ensures that the histories and cultures of resistance are rendered accessible at a different time for current and future generations [81] (n.p). To use Rebecca Schneider’s words, provision of broad access in this way happens ‘across multiple registers [and] in multiple media’ [33] (p. 7). This approach supports ‘strategic witnessing’ in serving a three-fold, critical objective at FA. First, it challenges conventional archival and preservation systems. Second, it counters dominant narratives about societal events, (hi)stories, and memories. Third, it affords wider publics ‘opportunities to piece together fragmented historical narratives drawing on new and multiple accounts’ based on those publics’ experiential knowledge [72] (p. 119; see also [76]). Clearly, this considerably helps FA to circumvent the existing institutional politics discussed under Section 4 that stymie the conservation and memorialisation of, and ongoing engagement with, radical left culture and heritage. FA further operationalises ‘strategic witnessing’ through a wider portfolio of activities and offerings.

Moore and Marks [81] (n.p) report that FA (1) ‘regularly produce[s] original documentaries and educational media [based on its archival collections] for use within schools and as tools for community building’, (2) ‘maintain[s] an active youth development program that encourages engagement with historical materials’, (3) ‘provides media production training as well as fostering a love for progressive history’, and (4) runs ‘strong, cooperative, and effective partnerships and project-based connections with a number of youth organizations, local high schools, community colleges, and 4-year colleges and universities’. Indeed, FA’s impact appears remarkable. ‘Since 2003’, Moore and Marks note, ‘hundreds of young people have passed through the archives as a result of [FA’s] program’ [81] (n.p). Beyond youth development, the co-directors observe that FA ‘has [not only] become a national and international source of media of great interest to young people and students, but also to teachers, diverse community organizations, media outlets, filmmakers, activists, historians, artists and researchers [81] (n.p). In Moore and Marks’ words, FA’s wide-ranging work as discussed thus far facilitates passive and active memorialisation of leftist heritage through ‘assist[ing] [people] in unearthing lessons of the recent past and lifting up voices intentionally removed from the dominant views of history [thereby] creating deeper understandings and decolonizing the past’ [81] (n.p). To this end, FA deploys ‘radical recordkeeping’ as a praxis of critical intervention. It is to this praxis that the discussion now turns.

5.2. ‘Radical Recordkeeping’ and the Potential of Interactive and Immersive Memorialisation

‘Radical recordkeeping’ is understood as the radical departure from traditional institutional acquisition and disposal policies and associated documentation, storage, and preservation conventions. It describes disruptive systems that subvert perceived conventional, rigid, and inflexible schema of classification used to arrange, organise, conserve, and present artefacts, collections, and records of various kinds [69,70,73,82]. Those disruptive systems tend to be typically employed by cultural, political, and social formations involving activist and politicised communities, entities, and groups that take the initiative to document their (hi)stories on their own terms. As one such entity, FA takes the concept of ‘radical recordkeeping’ further to capture ‘relationships and use from all aspects of creation, capture, organisation and pluralisation’ [82] (p. 173). ‘Pluralisation’ in particular evokes approaches to preservation that are akin to ‘leaderless and anti-hierarchical […] decentralised “anarchives” [that] offer a framework in which everyone can define their history’—one that ‘is made by ordinary individuals coming together to conduct acts in groups’ [83] (pp. 262–264; see also Monika Rodriguez and Michael Pierce [84]). Through taking a decentralised approach to preservation, FA demonstrates facilitation of acts of critical intervention undertaken in groups.

FA foregrounds participatory approaches to the passive and active memorialisation of the culture and heritage of left-wing, progressive movements through ‘radical recordkeeping’ as a praxis reflective of struggle and empowerment. For Moore and Marks, that empowerment begins with ‘a digital search engine that allows for increased access to [FA’s] holdings through a less academic and more user-friendly exploration of materials’ [81] (n.p). Through archival research, I found that FA maintains a very rich online archival resource that features fourteen major collections presented in alphabetical order—with each subdivided into numerous subcollections. The subcollection of most relevance for my purposes in this article is titled ‘African Liberation Movements’ within the ‘International Liberation Struggles’ collection. Materials on Amílcar Cabral and PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde can be accessed under a further subcollection titled ‘Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique’. As the title suggests, this subcollection also contains materials from liberation struggles in Angola led by The People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and in Mozambique led by the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO). According to FA, the subcollection ‘contains primary accounts, personal narratives and a graphic novel from the various wars of liberation’—the majority of which were produced by the respective liberation movements themselves [85] (n.p). The interface of FA’s archival website makes the materials accessible using a range of filters including (1) media type, (2) source format, (3) year of origin, (4) title, (5) subject, (6) author, and (7) keywords.

Altogether, the subcollection contains twelve items broken down into eleven documents in PDF format and one audio file as the media types. The materials originate from six richly illustrated monographs, three transcripts of interviews and speeches, two pamphlets, and one MP3 audio file, and date back to the period between 1971 and 1986. Although the materials are variously titled, they are closely intertwined with the following overarching subject areas typically tackled by leftist projects at micro and macro levels, albeit taking various approaches to intervention: (1) Africa, (2) national liberation, (3) anti-imperialism, (4) Marxism, (5) black liberation, (6) colonialism, (7) education, and (8) women. Later in this article, Section 7 will home in on the subject area of education—exploring how FA could use Metaverse-type environments and the fully developed Metaverse to animate the political education programme that Amílcar Cabral and PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde deftly instrumentalised in the struggle against colonial domination. Interestingly, the FA website interface lists forty-two further materials that are ‘hidden’ and designated with the notification ‘no digital version is available’. This is because those materials have not yet been digitised—very likely as a result of some of the infrastructural and resourcing challenges discussed under Section 4. Limited staffing capacity and issues of access and technology are cases in point. Archival research revealed that the non-digitised materials include radio news programmes on VHS cassette tapes, music and poems on radio cassette tapes, speeches on CD-ROMS as well as various analyses and statements written up in articles, monographs, pamphlets, periodicals, and publicity materials. Most of these artefacts were generated between the late 1950s and 1980s.

By providing access to materials documenting some of the key activities underpinning the learning curricular devised and delivered by Amílcar Cabral and PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde in this way, FA contributes vitally to the preservation of the passively stored memory of (1) ‘the hard work of those who [have] more generally advocated for societal improvements [including tackling widespread illiteracy through provision of accessible education]’ [2] (p. 1), and (2) their commitment to ‘disrupting the dominance of [the racialising, colonial education system] and mitigat[ing] actively against [the] silenced voices [of the colonised Guinean and Cape Verdean people]’ [86] (p. 73). However, the contention of this article is that memorialisation could be taken to an even greater level to achieve much wider efficacy. FA’s virtual archival collection is currently mostly static and even sterile but could benefit from animation and enhanced interactivity. A number of commentators have discussed possibilities offered by Web 2.0 to deliver interactive content in ways that allow users to interact with materials through immersion. Because interactive and immersive environments are highly complex and distinctly specialised and, therefore, very costly to construct and maintain despite the cost of technology gradually falling, it is mostly dominant digital platforms that have afforded them. One such digital platform is ‘Second Life’ [57,87]. For example, in his fascinating work that promotes social justice through preserving selected ‘dark heritage’ of Black US Americans dating back to the 1920s, the anthropologist Edward González-Tennant has drawn inspiration from heritage projects that have used interactive and immersive capabilities offered by ‘Second Life’ [57]. Although this would sound appealing to FA, other commentators have called for caution.

Andrew Prescott, for instance, draws on a digital humanities perspective8 [88] to suggest that avoiding the use of dominant digital platforms and tools in favour of adopting more autonomous and decentralised solutions offers a more hopeful and promising way forward [83]. The banning of Illma Gore’s Trump painting on Facebook and other popular digital platforms, as we saw earlier under Section 3.1, clearly shows that such platforms can be hostile to leftist critical interventions through seeking to exclude and silence critical voices and alternative perspectives. In their own recent research on this topic, Katherine Jarvie and colleagues substantiate this by arguing that dominant digital platforms ‘are a place for activism but also a place for censorship of radical voices’ [73] (p. 365). With the support and resources of a higher education institution and a number of foundations, Edward González-Tennant created an independent website that offers interactive and immersive capabilities that enable users to interact closely with leftist heritage outside the purview of established digital platforms—with a particular focus on a venture called the Rosewood Heritage and VR project [89]. Whilst FA operates its own archival website on its own terms, and those of its users, it does not appear to enjoy the same level of support and resources—despite maintaining partnerships with various entities. The same can be said for many leftist cultural projects as well as individuals, entities, and organisations undertaking heritage work widely considered. That said, the growing number of Metaverse-type environments and huge promise of the Metaverse as we are going to see under Section 6 and Section 7 below, may make a considerable difference.

In two recent, informative pieces of work on and around how activism, critical creative praxis, and consumer/user engagement could thrive through use of immersive technologies, Yee et al. [90] and Dwivedi et al. [91] point to the Metaverse that is currently under construction by engineers and creatives—one in which emancipatory technologies and spaces can be imagined, designed, and built both for individual and collective experiences and practices. These authors express optimism that if the Metaverse materialises in the foreseeable future, it ‘will be more immersive, open, accessible, and interactive than previous [digital] technologies’ [91] (p. 758). This could potentially take FA’s ‘strategic witnessing’ and ‘radical recordkeeping’ approaches to passive and active memorialisation of leftist, progressive struggles to a much higher level. In what follows based on what is currently known about the Metaverse, the discussion unpacks what it is, explores the opportunities and challenges that have been said to characterise it, and analyses how FA and other leftist projects could employ it for more interactive and immersive memorialisation.

6. The Metaverse: Context, History, and Definitional Issues

At the time of writing, what the Metaverse actually is remains unclear. Rory Greener observes that ‘[d]espite the popularity of the Metaverse, the concept is still unclear to many’ [92] (n.p). Following Yee et al. [90] and Dwivedi et al. [91], virtually all commentators put the lack of an explicit definition to the fact that the Metaverse is still being built and as such, embodies an unknown quantity. My meta-analysis of industry expert commentary and emerging scholarly research on this topic revealed a clear pattern. Many contributions approach discussion of the Metaverse from a predominantly commerce-oriented perspective—highlighting opportunities for business growth, sales enhancement, workforce efficiency and productivity, and profit maximisation predominantly in the realms of advertising, branding, construction, engineering, entertainment, fashion, finance, manufacturing, marketing, retail, service provision, and tourism.

Accounts do exist of how the Metaverse and associated infrastructures and technologies are being leveraged to address some major challenges afflicting social justice including (1) disparities in universal access to public services such as education and healthcare, (2) widespread poverty, and (3) social exclusion. For example, Metaverse Seoul—a pioneering, smart city government authority initiative in South Korea—offers ‘various public services while focusing on “freedom”, “inclusion”, and “connection”’ [93] (n.p). In Japan, cross-sectoral partnerships involving local government authorities and activists operating under the entity called ‘Whole Earth Foundation’ (WEF) collaborate on the administration and upkeep of infrastructures and associated public services using blockchain technologies (see Section 6.1) in the context of participatory governance [94].

On the whole, however, accounts of how the Metaverse could be used to champion social justice causes appear to be few and far between at the time of writing. That said, I assert that there is much that can be learnt from, and said about, the opportunities touted for business and enterprise in the Metaverse. Those opportunities are transferrable to the passive and active memorialisation of radical left culture and heritage more generally.

Two fervent champions of business opportunities in the Metaverse, in my view, have been McKinsey & Company and Deloitte by far. Drawing on new, extensive industry research, McKinsey & Company note that ‘[t]he [M]etaverse seems to be whatever people’s imaginations dream it to be [which renders it] difficult to define, even though the term has been in circulation for decades’ [95] (p. 10). Beyond varied and vivid imaginations—and the issues of definition they engender—the authors add that ‘the [M]etaverse is real, potentially revolutionary, and has the makings of a significant opportunity’ [95] (p. 10). Below, I argue how that ‘significant opportunity’ might meaningfully, effectively, and significantly enhance the passive and active memorialisation of FA’s subcollection on PAIGC’s learning programmes that underpinned the revolutionary movement in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde and ultimately contributed substantially to the demise of colonialism on the African continent. But before doing so, it is worth discussing what the Metaverse is shaping up to become. In doing so, it is helpful to place a particular focus on what the recent history of new media technologies might reveal about how the Metaverse might end up developing.

6.1. The Metaverse and Its ‘New Building Blocks’

In an attempt to show how the Metaverse will become reality sooner rather than later despite still being an unknown quantity, a number of commentators offer an interesting analogy premised on the understanding that the Metaverse will be the successor of the mobile Internet [94,95,96,97]. Blau et al. at Deloitte remark that because the Metaverse is still currently under construction, ‘trying to describe what it will be is like trying to describe to someone in 1990 what the Internet would become’ [98] (p. 3). In a similar vein, Eric Ravencraft observes that just as the Internet existed in the 1970s with no indication whatsoever of what it would eventually turn out to become fifty years later, so too is the Metaverse [96]. ‘[I]t’s too new to define what it means’, adds Ravencraft, but ‘there are some new building blocks in place’ [96] (n.p, emphasis in original). To understand these ‘new building blocks’ and the significance they hold, it is fruitful first to take a look at a brief historical overview of recent new media technologies. Doing so is instructive because it points to patterns of development that might be indicative of how the Metaverse could develop. It is worth taking the Internet as a prime example.

The Internet is not considered a singular technology but a series of new media technological innovations that have been gradually designed, tested, iterated, and applied as ‘building blocks’ to support connectivity, communication, processing, storage, and uptake at scale [99,100,101,102,103]. ‘Building blocks’ here have encompassed conventions; technical standards; compatibility considerations; communication protocols (that enable remote computers to connect to each other and to communicate); operating systems; regulatory frameworks; interfaces; the convergence of software and hardware; adoption and diffusion schemes; and more recently the shift from the World Wide Web (WWW) to digital platforms such as apps that use the Internet for access but not the browser for display [102,103,104,105,106,107].

Newer ‘building blocks’ can be added to this mix: Augmented Reality (AR); Virtual Reality (VR); Mixed Reality (MR); Neuro-enhanced Reality (NeR); blockchain technologies; networks and connectivity (e.g., 5G); computing power (e.g., cloud, edge); and Web 3.0 or Web3. AR describes a set of technologies that superimposes digital data, images, and other content on physical spaces—mostly via mobile devices such as smartphones, but increasingly via wearables including head-mounted displays (HMDs) and smart glasses [108,109]. VR depicts a set of technologies that immerses users in artificially constructed virtual environments in which users’ sense of presence is heightened—akin to the feeling of being submerged in those environments [110,111]. MR is said to combine VR and AR among other technologies through use of a series of cameras, sensors, and often Artificial Intelligence (AI)-enhanced technology to process data about a physical space and to use that information to create digitally-enhanced experiences that feel as immersive and realistic as possible [112,113]. MR does this by tracking object surfaces and boundaries as well as the positioning and movement of human beings in that environment [113,114]. NeR draws on methods of neurostimulation to enable users to smell certain types of scent via brain-computer/machine interfaces integrated in users’ HMDs [91]. NeR is said to offer greater technological embodiment due to its ability to bypass other intermediate stages of sensory perception by stimulating relevant brain regions directly [115].

Blockchain technologies describe infrastructures comprising decentralised databases that (1) are considered to be secure, (2) allow for the permanent, immutable, and transparent recording of data and related activities (e.g., cryptocurrency transactions), and (3) facilitate the sharing of information across networks with no hierarchies [94,116]. Effective information-sharing here hinges on very fast networks with low latency—understood as the time between instructing a wireless device to perform an action and that action being completed—to enable (1) simultaneous connectivity of a large number of devices at any one given time, and (2) the processing and transfer of vast volumes of data [95,97,98]. One such technology that connects networks at much greater speed is 5G with far greater capacity, and at considerably reduced latency9. All the ‘building blocks’ described thus far, commentators observe, will be able to function in an interoperable fashion—if considerable technological advances in computing power are made to enable the running of the Metaverse.

Edge computing in particular is singled out because it ‘enables data to be captured, stored, and processed locally across smart devices and local networks rather than in the cloud, [something that] helps solve problems of limited bandwidth and latency—critical for an immersive, high-fidelity experience’ [95] (p. 23). Web 3.0 or Web3—described as the third generation of the web—is being constructed to offer a decentralised architecture characterised by (1) no central authority, (2) a high degree of interoperability across different applications, data sources, networks, and technologies (such as the ‘building blocks’ depicted until this point), (3) greater accountability and security, and (4) considerable user empowerment [90,95,117,118]. In what follows next, it is worth looking at how the ‘building blocks’ described so far are already shaping the contours of what the Metaverse could become—including supplying useful working definitions, identifying areas for opportunities, and pointing towards key challenges.

6.2. ‘Metaverse Moments’: Opportunities and Challenges

The ‘building blocks’ described above tell us a great deal about the remarkable and rapid progress of new media technological advancements in recent years. In the particular context of the Metaverse, those technologies are not to be merely thought of as stand-alone and self-contained. To Blau et al., it is more helpful to think of them as a ‘convergence of several separate technologies [that] can create the experience of an immersive, three-dimensional environment in which users interact with their surroundings and other users as if they are in a shared space’ [98] (p. 3, emphasis in original). Beyond merely being a virtual space, the authors add, the Metaverse will include both the physical and digital/virtual worlds in the user’s experience. To Ed Greig, ‘[t]he more these components intertwine, the closer we get to a fuller version of the [M]etaverse’ [99] (n.p). In a podcast series titled At the Edge run by McKinsey & Company [100,119,120], a renowned futurist, consultant, and author on the Metaverse by the name of Cathy Hackl provides her working definition of the Metaverse. That definition, which follows below, underlines the centrality of the notion of convergence, and by extension, pulls the discussion of the ‘new building blocks’ of the Metaverse described up to this point neatly together:

I believe it’s a convergence of our physical and digital lives. It’s our digital lifestyles, which we’ve been living on phones or computers, slowly catching up to our physical lives in some way, so that full convergence. It is enabled by many different technologies, like AR and VR, which are the ones that most people tend to think about. But they’re not the only entry points. There’s also blockchain, which is a big component, there’s 5G, there’s edge computing, and many, many other technologies. To me, the [M]etaverse is also about our identity and digital ownership. It’s about a new extension of human creativity in some ways. But it’s not going to be like one day we’re going to wake up and exclaim, ‘The metaverse is here!’ It’s going to be an evolution [120] (n.p).

McKinsey & Company helpfully summarise the working definitions of the Metaverse presented above in two categories (i.e., basic and advanced)—with each comprising three key tenets. ‘At its most basic, the [M]etaverse will have three features: (1) a sense of immersion, (2) real-time interactivity, and (3) user agency’ [95] (p. 11). In its fully advanced form, it will include: ‘(1) interoperability across platforms and devices, (2) concurrency with thousands of people interacting simultaneously, and (3) use cases spanning [many areas of] human activity’ [95] (p. 11). Emerging scholarly work and industry commentary (including my own research) on and around developments in Metaverse-type environments reveal that some of these features—basic and advanced alike—are already being witnessed, and associated technologies being applied, in primarily business, enterprise, entertainment, and manufacturing realms (though not exclusively as we shall see shortly). For example, ‘interoperability across platforms and devices’ is already occurring where MR (i.e., an environment in which both physical and virtual worlds co-exist) is being applied to enhance engagement and interaction with variously packaged offerings intended to educate, entertain, and provide memorable (immersive and non-immersive) experiences in the hospitality and tourism industries [91,109,114,121].

Likewise, ‘use cases spanning many areas of human activity’ are continually being identified. For instance, the German automobile brand—BMW—has recently completed the design and launch of its latest digital twin10 [95,98,108,122]. plant which will house the production of all the brand’s electric vehicles in due course [119]. Capitalising on the interoperability of the ‘building blocks’ depicted above—including the convergence of physical and virtual worlds, BMW is enabling its work teams spread across its thirty or so manufacturing sites worldwide to collaborate in real-time on holograms11 of vehicle prototypes [122]. Work teams can access the life-size holograms from any angle to work on design details without having to build expensive physical prototypes. Furthermore, those teams do not have to travel to a particular manufacturing site to carry out that work. A key lesson here is that a fully developed Metaverse would offer a great, efficient, and productive space to experiment and explore first at low cost and at great length before designing and producing for the real world. This would apply to both commercial and non-commercial contexts. In the latter context as we shall see in Section 7.3, one can vision FA’s Metaverse users accessing and working on the materials documenting the learning programmes designed and delivered by Amílcar Cabral and PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde during the liberation struggle in ways that (1) question absences and silences, (2) challenge and reinterpret existing knowledge, (3) correct taken-for-granted insights and truths, and (4) produce wholly new knowledge and deeper understandings based on multi-vocal accounts.

Earlier under Section 6, I briefly mentioned the ‘Whole Earth Foundation’ (WEF) and its distinctive work which is activist and non-commercial in nature. WEF utilises blockchain technologies driven by a Web3 platform called ‘Tekkon’ to champion ‘social good by empowering users (citizens) to help fix their local community’s infrastructure’ [123] (n.p). According to a recent news account [124], Tekkon crowdsources information about the condition of public utilities such as power lines and water networks in a number of countries, particularly in Southeast Asia. Crowdsourcing participants are remunerated through payment in cryptocurrency which can be exchanged in physical currency. The information collected is sold to utility companies not to make profit but to support (1) the remuneration of crowdsourcing participants, and (2) the sustenance of WEF’s activist operational needs. The overarching rationale for this, from the perspective of WEF, is two-fold. First, to help lower the cost of maintenance by flagging up urgent utility cases that need to be prioritised. This is extremely important considering that persistent austerity is limiting the ability of government authorities to provide comprehensive maintenance. Second, to stimulate a sense of civic engagement amongst local communities as part of efforts to strengthen decentralised governance models whose ultimate aim is to foster accountability, transparency, and sustainability [94,124]—all of which are central goals typically pursued by leftist projects.

I argue that the knowledge and learning from these use case examples—including the opportunities they present—are not only transferable and valuable to other areas of human activity, but also reflect glimpses of the Metaverse that Cathy Hackl calls ‘Metaverse Moments’ [120]. In Section 7, we are going to look at what those ‘moments’ might mean in terms of considerably enhancing the passive and active memorialisation of FA’s subcollection on the political education programme that impelled the liberation struggle led by Amílcar Cabral and PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. For now, it is worth turning our attention to some of the key aspects that could pose serious challenges to those ‘moments’. In the words of Ed Greig, while [m]any of the [M]etaverse ingredients are with us now’ [99] (n.p) and have largely elicited feelings of anticipation, other commentators have observed mixed reactions [97,101,108,119]. Hadi et al., for example, note ‘sentiments ranging from excitement, fascination, and hope, to confusion, skepticism, and even fear’ [125] (p. 1). The less positive sentiments, it might be argued, are grounded in key historical precedents that give cause to temper that ‘excitement’ and ‘hope’ with realism. McKinsey & Company capture this brilliantly when contextualising the widely perceived transformative potential of the Metaverse:

Such generational changes rarely happen overnight. They tend to take years and are the result of an accumulation of incremental advances, driven by an ethos of experimentation on platforms that allow creativity to flourish. And because they ultimately result in fundamental changes to our lives, they may also present risks for individuals and society [95] (p. 57).

Whereas some risks are known, others are not12 [126]. Again, taking the recent history of the Internet as an illustrative example here is helpful. A crucial lesson is that investing a lot of thought and work in learning from mistakes made in the context of developing the mobile Internet would substantially benefit the construction of the Metaverse as a truly accessible and transformative environment. For a range of reasons, the design of the Internet has turned out not to provide a user experience that is accessible to all [64,127,128,129]. If the Metaverse is designed and constructed with the (dis)abilities, neurodiverse conditions, and needs of all users in mind, then it would be a genuinely accessible environment. Issues of privacy and trust on the Internet, in relation to the indiscriminate collection and exploitative use of user data, continue to pose a recurrent challenge [128,129,130]. Many of the ‘building blocks’ discussed under Section 6.1—to use the words of Richard Ward in his capacity as an expert technologist—‘record and gather an incredible amount of personal data [meaning] the full [M]etaverse experience [will] go to the next level of data collection’ [119] (n.p). If user data are collected and used responsibly—including secure storage, then the Metaverse would be a more trusted environment.

Time after time, Internet users (and their property) have been harmed through acts that have ranged from various kinds of abuse to deception to hacking to harassment to misinformation [100,104,107]. If the codes of conduct set up to regulate behaviour and engagement with content are fair and non-exploitative—and enforced justly, the Metaverse would be a well-governed environment. Putting in place stronger safeguards to block harmful acts would not only improve good governance, but also render the Metaverse a much safer environment. Speaking of governance, giant global tech corporations have been reported to have amassed and concentrated enormous control and power of Web 2.0 and related digital platforms for their sole business interests [48,106,116,128,131,132]. According to Dal Yong Jin, this consolidation of dominance has manifested itself through (1) engendering ‘asymmetrical information flows and discrimination [in the design and use of digital platforms]’, and (2) ‘establishing norms and attitudes about [platform] uses, standards, and practices of systemic colonisation’ [129] (p. 13). The ever-present tension between intellectual property rights (IPR) on the one hand, and sharing and re-use on the other, is a case in point. Clearly, this militates against the vision of the Metaverse as a fair, open, and interoperable environment that is not at the mercy of hegemons. Sadly, those hegemons are already jostling and positioning themselves as best as they can to exploit the Metaverse for their own corporate ends [101]. No wonder ‘confusion’, ‘scepticism, and ‘fear’ abound in relation to what the Metaverse might end up looking like.