Rural Landscapes as Cultural Heritage and Identity along a Romanian River

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How are rural landscape and rural identity constructed at the local level?

- What role does the river Mureș play in shaping the rural and regional belonging of the country people in the area?

2. Theoretical Background

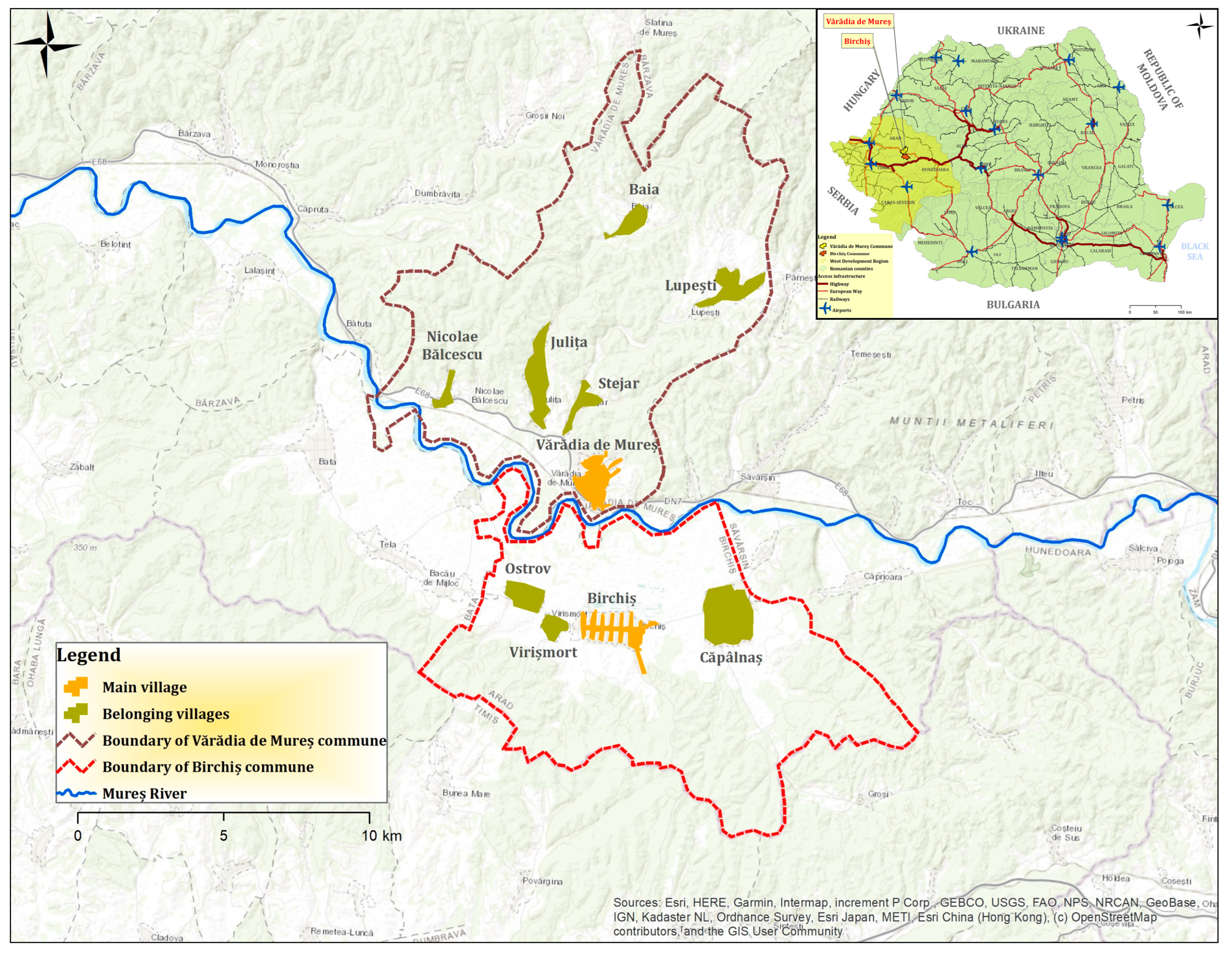

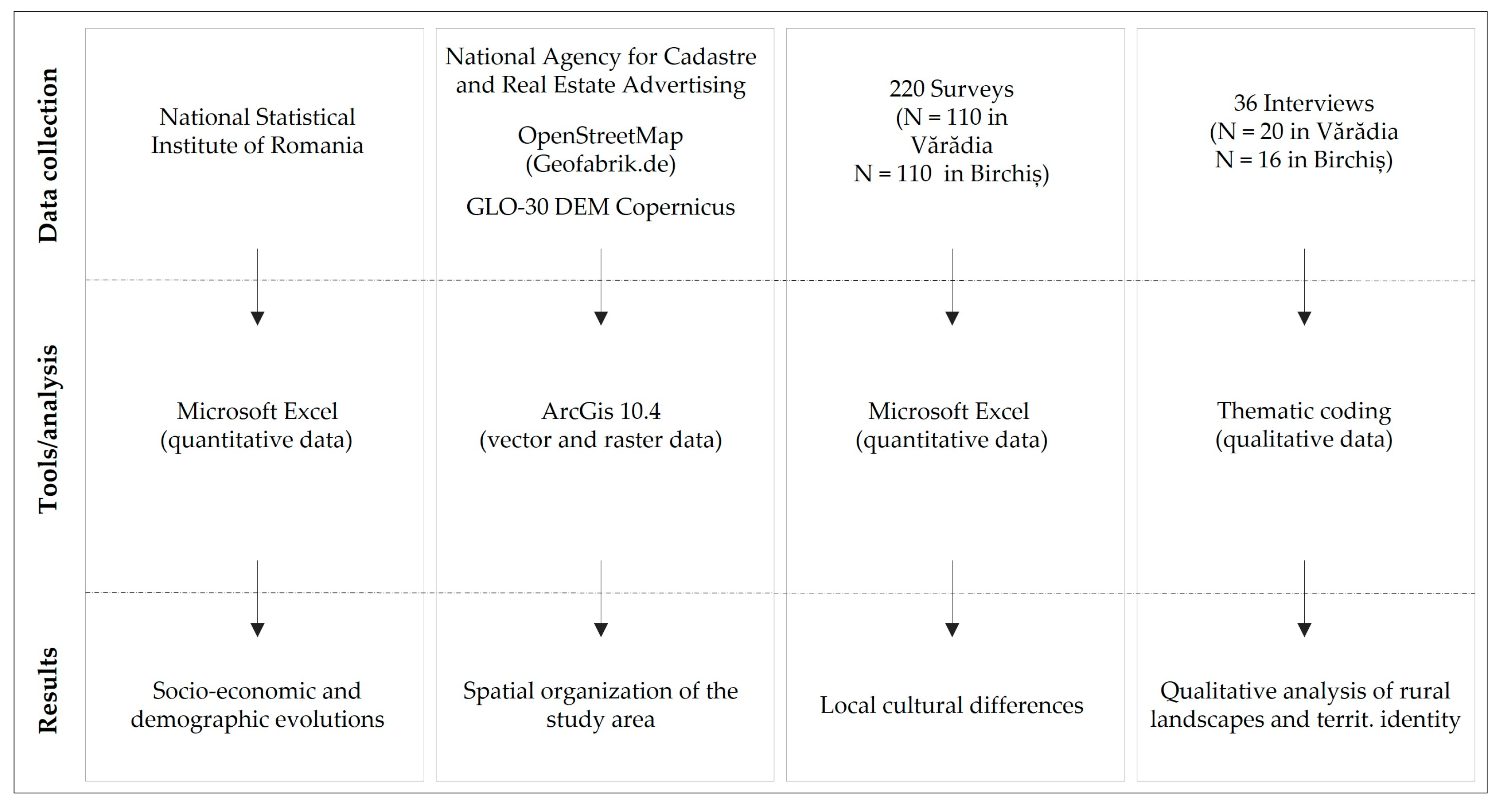

3. Study Area, Materials and Methods

4. Results

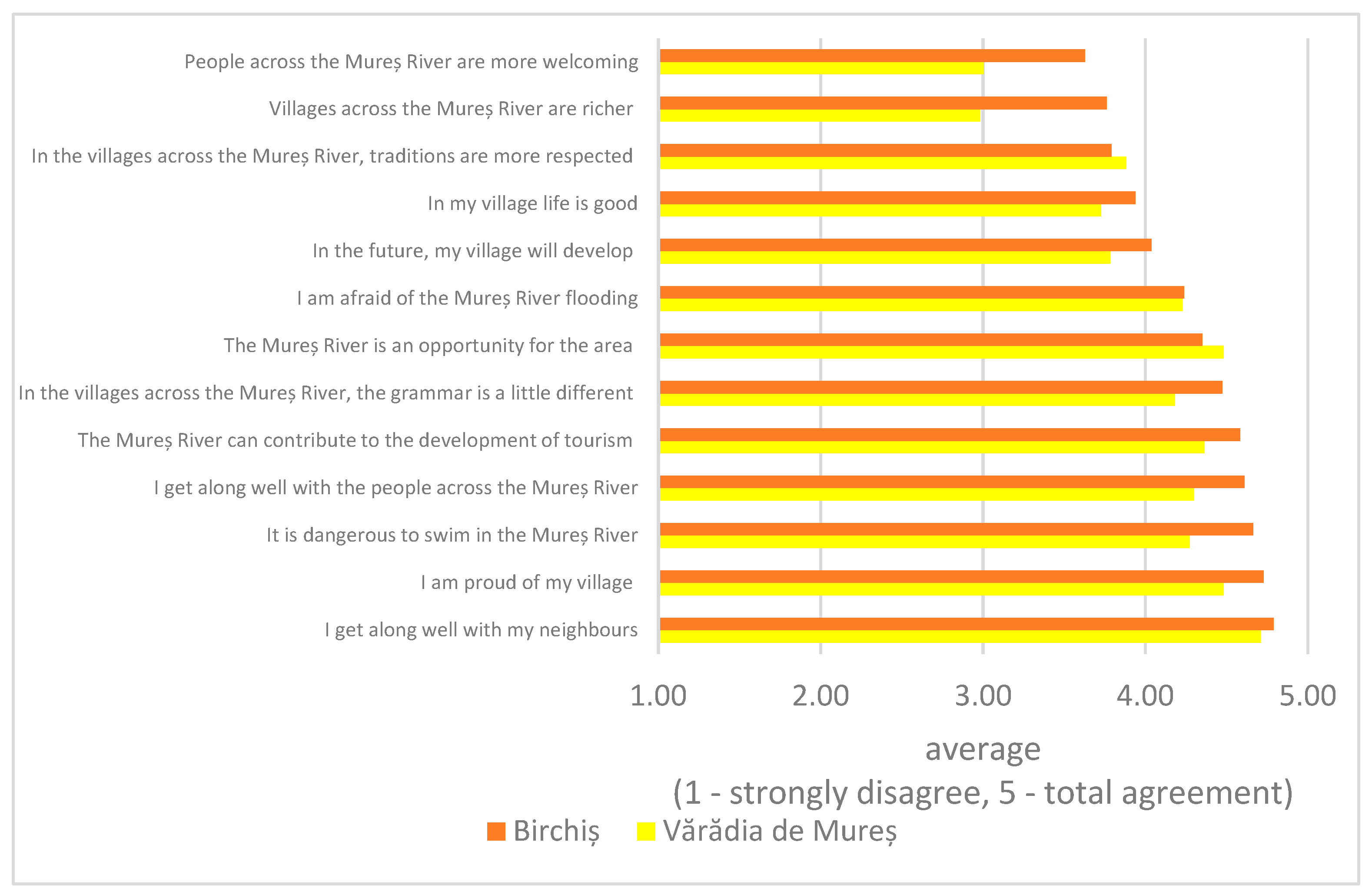

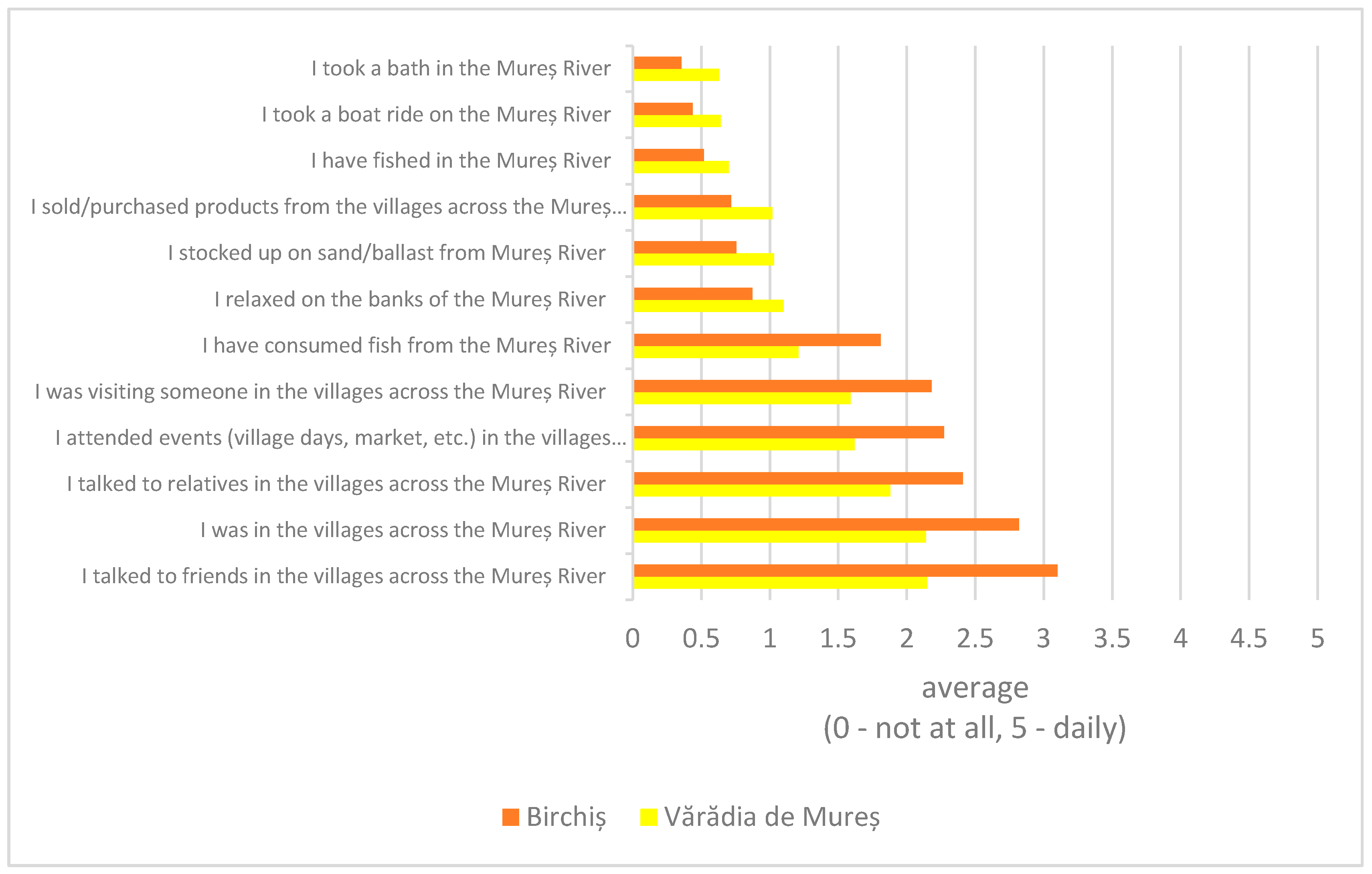

4.1. A Quantitative Approach to Local Cultural Heritage Differences

4.2. A Qualitative Analysis of Rural Landscapes and Territorial Identity

4.2.1. A Broader Perspective on the Rural Lived Rural Space

4.2.2. The Mureș: The Balance between Benefits and Risks at the Local Rural Level

4.2.3. Imagery of Regional Belonging at the Border between the Banat and Crișana Regions

4.2.4. Main Disadvantages of the Rural Areas Studied

4.2.5. The Voice of Local Residents: Ideas, Visions, Beliefs, and Suggestions

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Banini, T.; Ilovan, O. Representing Place and Territorial Identities in Europe; Springer International Publishing: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976; Volume 67, 156p. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; 442p. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. Questions of locality. Geography 1993, 78–82, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Paasi, A. Region and place: Regional identity in question. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2003, 24, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R. On the Concept of Territorial Competitiveness: Sound or Misleading? Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 2395–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane, P. Environmental Sustainability and Territorial Competitiveness: A Comparison between Italian Provinces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, P.; Graziano, P.; Dallara, A. A capacity approach to territorial resilience: The case of European regions. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2018, 60, 285–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, V. Water: Nature and Culture; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 2015; 224p. [Google Scholar]

- Sipos, G.; Blanka-Végi, V.; Ardelean, F.; Onaca, A.; Ladányi, Z.; Rácz, A.; Urdea, P. Human-nature relationship and public perception of environmental hazards along the Maros/Mureş River (Hungary and Romania). Geogr. Pannonica 2022, 26, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkon, A.; Traugot, M. Place matters, but how? Rural identity, environmental decision making, and the social construction of place. City Community 2008, 7, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Rural geography: Blurring boundaries and making connections. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 3, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R. Cultural politics and the hydrosocial cycle: Water, power and identity in the Andean highlands. Geoforum 2014, 57, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R. Water, Power and Identity: The Cultural Politics of Water in the Andes; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boelens, R.; Getches, D.; Guevara-Gil, A. Water struggles and the politics of identity. In Out of the Mainstream: Water Rights, Politics and Identity; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Terlouw, K. Iconic site development and legitimating policies: The changing role of water in Dutch identity discourses. Geoforum 2014, 57, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; Turnock, D.; Woudstra, J. Identity and multiculturalism in the Romanian Banat. Méditerranée 2008, 110, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berceanu, I.; Popa, N.; Creţan, R. Towards a regional crossover model? The roles played by spatial vicinity and cultural proximity among ethnic minorities in an East-Central European borderland. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2023, 15, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R. Who owns the name? Fandom, social inequalities and the contested renaming of a football club in Timisoara, Romania. Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Porta, D.; Diani, M. Social Movements: An Introduction; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; 384p. [Google Scholar]

- Glemain, P.; Bioteau, E.; Dragan, A. Les finances solidaires et l’économie sociale en Roumanie: Une réponse de “proximités” à la régionalisation d’une économie en transition? Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2013, 84, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkli, J.; Paasi, A. Geography, space and identity. In Voices from the North: New Trends in Nordic Human Geography; Öhman, J., Simonsen, K., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2003; pp. 141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.; Paasi, A. Guest Editorial: Regional world(s): Advancing the geography of regions. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A.; Harrison, J.; Jones, M. Handbook on the Geographies of Regions and Territories; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2018; 544p. [Google Scholar]

- Terlouw, K. Local Identities and Politics: Negotiating the Old and the New; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; 154p. [Google Scholar]

- Doiciar, C.; Creţan, R. Pandemic populism COVID-19 and the rise of the nationalist AUR party in Romania. Geogr. Pannonica 2021, 25, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, M. Governmentality, subject-building, and the discourses and practices of devolution in the UK. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2003, 28, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, M. Building new subjectivities: Devolution, regional identities and the re-scaling of politics. In Territory, Identity and Spatial Planning; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 320–334. [Google Scholar]

- Beel, D.; Jones, M. Region, Place, Devolution: Geohistory still matters. In The Routledge Handbook of Place; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Guibernau, M. National identity, devolution and secession in Canada, Britain and Spain. Nations Natl. 2006, 12, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Popa, N. Social Economy in Post-communist Romania: What Kind of Volunteering for What Type of NGOs? J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2017, 19, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Deconstructing regions: Notes on the scales of spatial life. Environ. Plan. A 1991, 23, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. The region, identity, and power. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 14, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Regional planning and the mobilization of ‘regional identity’: From bounded spaces to relational complexity. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1206–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, G. Territorial competitiveness and local and regional economic development: A classic tale of ‘theory led by policy’. In Handbook of Local and Regional Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 344–355. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. Territorial Competitiveness and Development Policy; Orkestra Basque Institute of Competitiveness: Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, 2008; Volune 31, p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M.; Chakraborty, A.; Chakraborty, S. Rivers and Society Landscapes, Governance and Livelihoods; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Valdaliso, J.M.; Wilson, J.R. Strategies for Shaping Territorial Competitiveness; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2015; 276p. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, P.; Parrilli, M.D.; Curbelo, J.L. (Eds.) Innovation, Global Change and Territorial Resilience; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; 512p. [Google Scholar]

- Martuwarra, R.; Unamen, S.; Poelina, A.; Wooltorton, S.; Guimond, L.; Sioui Durand, G. Hearing, voicing and healing: Rivers as culturally located and connected. River Res. Appl. 2022, 38, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.P.; Jackson, S.; Tharme, R.E.; Douglas, M.; Flotemersch, J.E.; Zwarteveen, M.; Arthington, A.H. Understanding rivers and their social relations: A critical step to advance environmental water management. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2019, 6, e1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schillinger, K.; Lycett, S.J. The flow of culture: Assessing the role of rivers in the inter-community transmission of material traditions in the upper Amazon. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2019, 26, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, K. Rivers as Bridges–Rivers as Boundaries Some Reflections on Intercultural Exchange on the Danube. Ethnol. Balk. 1997, 1, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Borthwick, A.G.; Ni, J. Human affinity for rivers. River 2022, 1, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.F. A River Forever Flowing: Cross-Cultural Lives and Identities in the Multicultural Landscape; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2003; 200p. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, C.A.; Reo, N.J.; Turner, D.A.; Cook, J.; Dituri, F.; Fessell, B.; Wilson, M. “The river is us; the river is in our veins”: Re-defining river restoration in three Indigenous communities. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavili, F.; Gkounta, S. Rivers to live by: The economic, social, cultural benefits of rivers and the role of architecture in its enhancement. Sustain. Mediterr. Constr. 2015, 2, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. The Cultural Value of Rivers: The Case of the Loire. In Theme Water and Cultural Diversity, Proceedings of the Third World Water Forum, Kyoto, Japan, 16–23 March 2003; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 319–326. [Google Scholar]

- Voiculescu, S. Timisoara and the culture of water. In The Romanian Post-Socialist City: Urban Renewal and Gentrification; Voiculescu, S., Creţan, R., Ianăş, A., Satmari, A., Eds.; Universitatii de Vest: Timisoara, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pavel, S.; Jucu, I.S. Urban transformation and cultural evolution of post-socialist European cities. The case of Timisoara (Romania): From ‘Little Vienna’urban icon to European Capital of culture (ECoC 2021). City Cult. Soc. 2020, 20, 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, P. Reproduction of the identity of a region: Perceptual regions based on formal and functional regions and their boundaries. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2023, 105, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridanpää, J. Imagining and re-narrating regional identities. Nord. Geogr. Publ. 2015, 44, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, L.A. Using the past to construct territorial identities in regional planning: The case of Mälardalen, Sweden. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anděl, J.; Balej, M.; Bobr, L. Landscape types and regional identity–by example of case study in Northwest Bohemia. AUC Geogr. 2019, 54, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonsich, M. Meanings of place and aspects of the Self: An interdisciplinary and empirical account. GeoJournal 2010, 75, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlouw, K. Transforming identity discourses to promote local interests during municipal amalgamations. GeoJournal 2018, 83, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvoll, S.; Rye, J.F. Elite discourses of regional identity in a new regionalism development scheme: The case of the ‘Mountain Region’ in Norway. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. -Nor. J. Geogr. 2009, 63, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainikka, J. The role of identity for regional actors and citizens in a splintered region: The case of Päijät-Häme, Finland. Fenn. -Int. J. Geogr. 2013, 191, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semian, M.; Chromý, P. Regional identity as a driver or a barrier in the process of regional development: A comparison of selected European experience. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. -Nor. J. Geogr. 2014, 68, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.; Utych, S.M. You’re not from here!: The consequences of urban and rural identities. Political Behav. 2021, 45, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, S. Rural Identities: Ethnicity and Community in the Contemporary English Countryside; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; 170p. [Google Scholar]

- Molnárová, K.J.; Skřivanová, Z.; Kalivoda, O.; Sklenička, P. Rural identity and landscape aesthetics in exurbia: Some issues to resolve from a Central European perspective. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2017, 25, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezák, P.; Dobrovodská, M. Role of rural identity in traditional agricultural landscape maintenance: The story of a post-communist country. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 43, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Leal, J. Rural tourism and national identity building in contemporary Europe: Evidence from Portugal. J. Rural. Stud. 2015, 38, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A. Rurality, identity and morality in remote rural areas in northern Spain. J. Rural. Stud. 2014, 35, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, N. Bridging identity divides in current rural social mobilisation. Identities 2013, 20, 598–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messely, L.; Dessei, J.; Lauwers, L.H. Regional identity in rural development: Three case studies of regional branding. Appl. Stud. Agribus. Commer. 2010, 4, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, V. Substantial connections: Water and identity in an English cultural landscape. Worldviews Glob. Relig. Cult. Ecol. 2006, 10, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatout, S. ‘States’ of scarcity: Water, space, and identity politics in Israel, 1948–59. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2008, 26, 959–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestigaard, T. Water, Culture and Identity: Comparing Past and Present Traditions in the Nile Basin Region; BRIC: London, UK, 2009; 272p. [Google Scholar]

- Ruru, J. The right to water as the right to identity: Legal struggles of indigenous peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand. In The Right to Water; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Bilotta, E.; Bonnes, M.; Ceccarelli, M.; Martorella, H.; Carrus, G. Local identity and the role of individual differences in the use of natural resources: The case of water consumption. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommes, L.; Boelens, R. Urbanizing rural waters: Rural-urban water transfers and the reconfiguration of hydrosocial territories in Lima. Political Geogr. 2017, 57, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P.; Cook, I.; Crang, P.; Goodwin, M.; Painter, J.; Philo, C. Practicing Human Geography; Sage: London, UK, 2000; 440p. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, D.H.; Herb, G.H. How geography shapes national identities. Natl. Identities 2011, 13, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, M.; Alem, N.; Edwards, S.J.; Blanco Coariti, E.; Cauthin, H.; Hudson-Edwards, K.A.; Sánchez, M.O. Community exposure and vulnerability to water quality and availability: A case study in the mining-affected Pazña Municipality, Lake Poopó Basin, Bolivian Altiplano. Environ. Manag. 2017, 60, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamfir, D.; Stoica, I.V. Demographic Changes and Challenges of Small Towns in Romania. In Urban Dynamics, Environment and Health; Sinha, B.R.K., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dragan, A.; Crețan, R.; Bulzan, R. The spatial development of peripheralisation: The case of smart city projects in Romania. Area 2023, 56, e12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSEE. Statistical Data. The Romanian Institute of Statistics/Tempo Online. 2023. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro/shop/ (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Ianoș, I.; Cocheci, R.-M.; Petrișor, A.-I. Exploring the Relationship between the Dynamics of the Urban–Rural Interface and Regional Development in a Post-Socialist Transition. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qual. Res. 2006, 6, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; Covaci, R.N.; Jucu, I.S. Articulating ‘otherness’ within multiethnic rural neighbourhoods: Encounters between Roma and non-Roma in an East-Central European borderland. Identities 2023, 30, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancuța, C.; Jucu, I.S. Sustainable Rural Development through Local Cultural Heritage Capitalization—Analyzing the Cultural Tourism Potential in Rural Romanian Areas: A Case Study of Hărman Commune of Brașov Region in Romania. Land 2023, 12, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T.; Creţan, R.; Jucu, I.S.; Covaci, R.N. Internal migration and stigmatization in the rural Banat region of Romania. Identities 2023, 30, 704–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.; Campbell, L.M.; Hay, C.J.; Naesje, T.F.; Ndumba, A.; Purvis, J. Rivers as resources, rivers as borders: Community and transboundary management of fisheries in the Upper Zambezi River floodplains. Can. Geogr. 2007, 51, 280–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasiński, D.; Meinhof, U.H. Looking across the river: German-Polish border communities and the construction of the Other. J. Lang. Politics 2002, 1, 23–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, N.; Dragan, A.; Marian-Potra, A.C.; Matichescu, M.L. Opportunities: Source of synergy, or of conflict? Positioning of creative industry actors within a European Capital of Culture Project. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Interview Code | Gender | Age Group | Occupation | Educational Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | F | 60–65 | Industrial worker | Secondary school |

| I2 | F | 60–65 | Teacher | High school |

| I3 | M | 60–65 | Retired army officer | High school |

| I4 | M | 35–40 | Economist | University |

| I5 | F | 35–40 | Nurse | High school |

| I6 | F | 60–65 | Carer | Secondary school |

| I7 | M | 55–60 | Social worker | High school |

| I8 | F | 50–55 | Social worker | High school |

| I9 | F | 35–40 | Carer | Secondary school |

| I10 | F | 60–65 | Industrial worker | Secondary school |

| I11 | F | 35–40 | Economist | University |

| I12 | F | 55–60 | Meteorologist | University |

| I13 | F | 40–45 | Economist | University |

| I14 | F | 50–55 | Farmer | High school |

| I15 | M | 50–55 | Industrial worker | University |

| I16 | F | >80 | Shop manager | Secondary school |

| I17 | F | 20–25 | Student | University |

| I18 | M | 70–75 | Driver | Secondary school |

| I19 | F | 45–50 | Hydrologist | High school |

| I20 | M | 50–55 | Electro-mechanical engineer | High school |

| I21 | F | 45–50 | Teacher | University |

| I22 | F | 35–40 | Farmer | High school |

| I23 | F | >80 | Farmer | Secondary school |

| I24 | M | 20–25 | Farmer | High school |

| I25 | M | >80 | Forestry worker | Secondary school |

| I26 | F | >80 | Farmer | Primary school |

| I27 | M | 55–60 | Forestry worker | High school |

| I28 | M | 20–25 | Student | University |

| I29 | F | 40–45 | Biologist | University |

| I30 | M | 45–50 | Builder | High school |

| I31 | M | 55–60 | Teacher | University |

| I32 | M | 70–75 | Carer | High school |

| I33 | F | 25–30 | Nurse | University |

| I34 | F | >80 | Cook | Primary school |

| I35 | M | 20–25 | Student | University |

| I36 | M | 66–70 | Veterinarian | High school |

| Selected Methods and Themes | Major Results |

|---|---|

| The quantitative approach to local cultural heritage differences Themes 1. Localism/rootedness; 2. (Regional) pride; 3. Rural authenticity 4. Different socio-economic uses of the Mures river. | The village is the primary locus of attachment for its inhabitants, extending beyond the conventional boundaries of attachment to country, region, or Europe. |

| People living south of the Mures river are more attached to the historic region of Banat, while those to the north are more attached to Crișana region. | |

| The relationship between the inhabitants and the Mures River is complex and multifaceted. The Mures River occupies the lowest position in the hierarchy of identity preferences. Conversely, the river is regarded as a multifaceted resource. | |

| Residents’ interactions (i.e., family visits, attending events/fairs) on either side of the river are rare. | |

| Despite the river’s provision of resources, the local population perceives it as a danger and rarely engages in activities such as swimming, sunbathing, boating, or fishing. | |

| Qualitative approach Themes 1. A broader per-spective on the rural lived space | Local people have a sentiment of nostalgia for the past, holding the view that traditions and the prevailing modes of conduct in the present have undergone a decline. |

| 2. The Mureș: benefits and risks at the local rural level | The Mureș river is a significant resource for the local population. It provides fertile agricultural land, moisture for plants, building materials, and drinking water for animals. However, it also poses a significant risk of flooding and drowning, with fatalities reported in both villages. |

| 3. Imagery of regional belonging at the border between the Banat and Crișana regions | Residents hold more favorable opinions of individuals residing across the river than they do of themselves. |

| 4. Disadvantages of the rural areas studied | The absence of a proximate urban center has precipitated an economic downturn and a migration of younger individuals. This is the primary rationale for the dearth of socio-economic and cultural vibrancy in the villages. |

| 5. The voice of local residents: visions and suggestions | The proximity of the King of Romania’s Castle (less than 10 km from both villages) and the existence of a European road and railroad present promising prospects for the area. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dragan, A.; Creţan, R.; Jucu, I.S.; Oancea, O.A. Rural Landscapes as Cultural Heritage and Identity along a Romanian River. Heritage 2024, 7, 4354-4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7080205

Dragan A, Creţan R, Jucu IS, Oancea OA. Rural Landscapes as Cultural Heritage and Identity along a Romanian River. Heritage. 2024; 7(8):4354-4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7080205

Chicago/Turabian StyleDragan, Alexandru, Remus Creţan, Ioan Sebastian Jucu, and Oana Andreea Oancea. 2024. "Rural Landscapes as Cultural Heritage and Identity along a Romanian River" Heritage 7, no. 8: 4354-4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7080205

APA StyleDragan, A., Creţan, R., Jucu, I. S., & Oancea, O. A. (2024). Rural Landscapes as Cultural Heritage and Identity along a Romanian River. Heritage, 7(8), 4354-4373. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7080205