Harnessing Vernacular Knowledge for Contemporary Sustainable Design through a Collaborative Digital Platform

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Digital Platforms for Managing Cultural Heritage

- Lehmbau im Weinviertel [22] is created by the Think Spacial! project with the goal of cataloguing earthen constructions in the Weinviertel region of Austria. A crucial component of the project is the engagement of Citizen Science, which involves the participation of local individuals in the process of mapping heritage [12].

- Mapa da Terra, focused on sharing knowledge on sustainable methods of construction [28,29]. It is a collaborative cartography showcasing building experiences using natural materials. The initiative intends to cultivate a network of individuals who are interested in sustainability and natural construction, with the intention of inspiring them through the platform’s content;

- Mediterrenet [30] collects and geolocates professionals who are experts in earthen building techniques.

- MEA (Map of Earthen Architectures) [35], a project by Associazione Internazionale Città della Terra Cruda, aims to crowdsource information on earthen architecture, including its network of experts and related events in Italy.

2.2. VerSus Wheel: 15 Sustainable Principles to Codify Lessons from Vernacular Knowledge

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Objectives and Methodological Approach

3.1.1. Fostering a Case-Based Reasoning Approach to Integrate Vernacular Lessons into More Conscious Design

3.1.2. Enhancing a Network of People Interested in Sustainability and Vernacular Heritage through a Collaborative and Inclusive Tool

3.1.3. Enhancing User Experience and Usability in the Heritage for People Platform

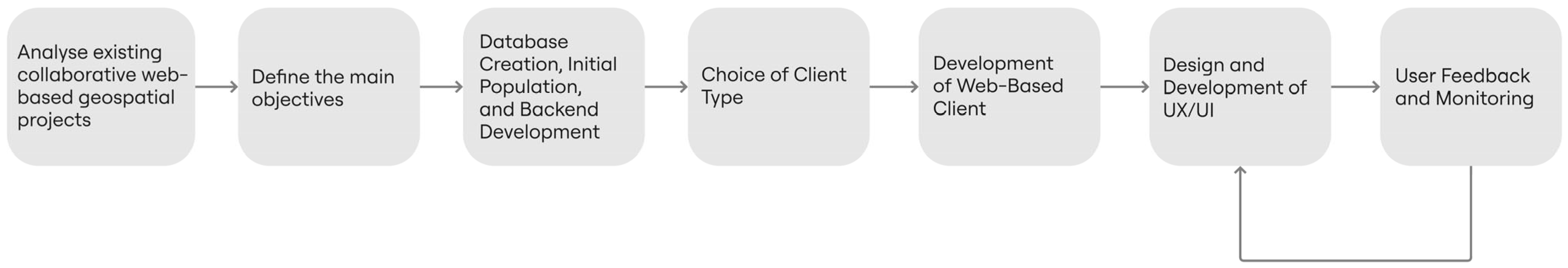

3.2. Technical Development and UX/UI Design

3.2.1. Database Creation, Initial Population, and Backend Development

3.2.2. Choice of Client Type

3.2.3. Development of Web-Based Client

3.2.4. Design and Development of UX/UI

3.3. Monitoring, Feedback, and Implementation

- All participants found the app useful, particularly valuing its classification, documentation, and mapping features.

- Some participants encountered issues with uploading images, locating entries, and linking to external material. They also suggested enhancements, such as adding PDF presentations, detailed references for each image, reducing upload times, and improving map functionality.

- All participants reported that the process of adding a new feature was easy.

- Most participants expressed a desire to use and consult the app in the future.

4. Results

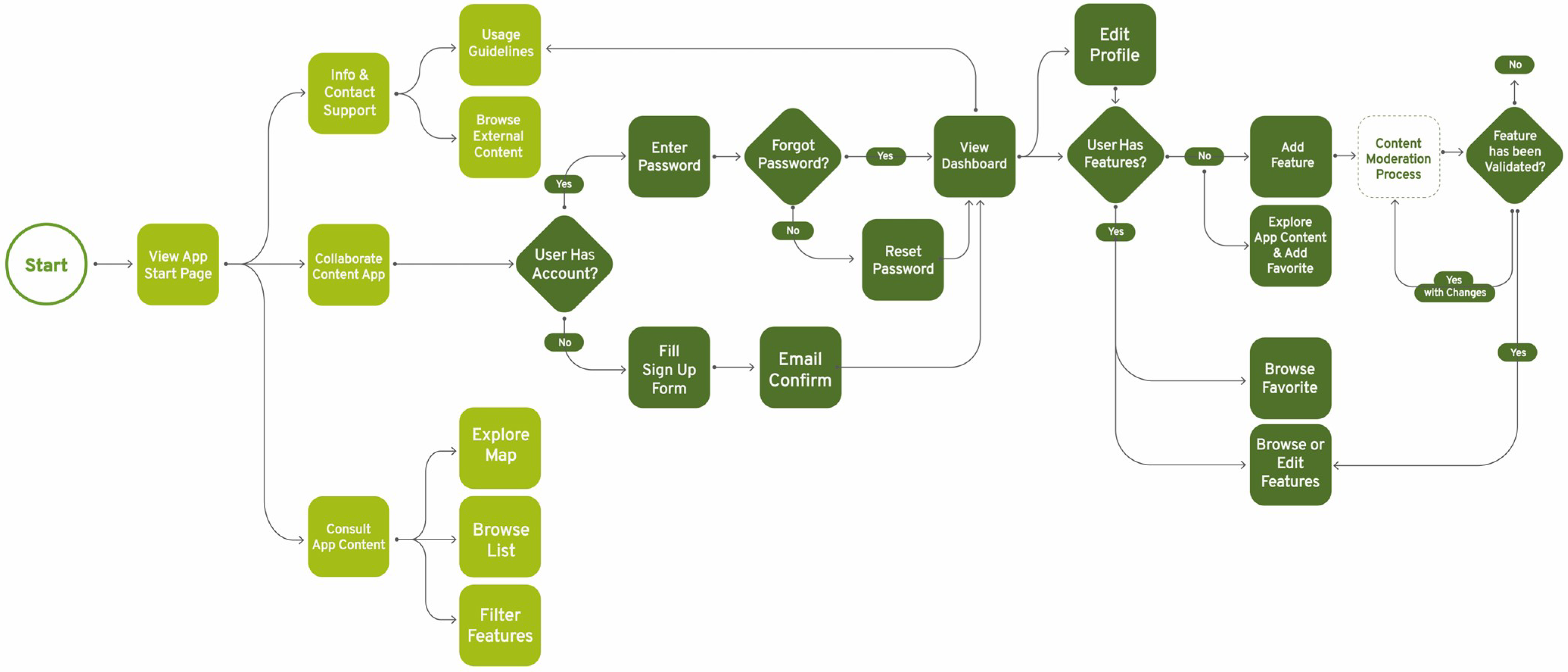

4.1. Description of the Prototype: Flows and Functionality

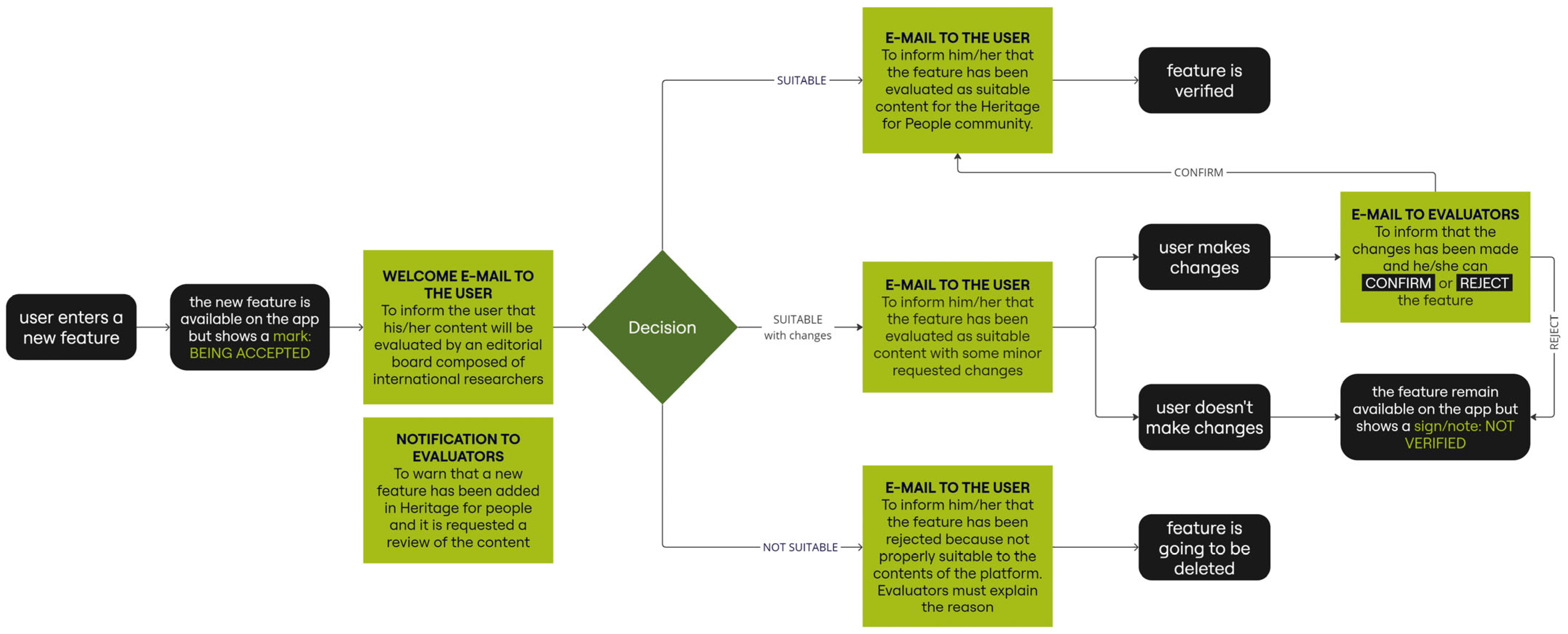

4.2. Content Moderation Process

5. Discussion

5.1. Systematisation of Vernacular Knowledge

5.2. Knowledge Sharing, Collaborative, and Inclusive Approach

5.3. User Experience and Accessibility

5.4. Engaging Students and Educative Approach

5.5. Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, A.T.; Truong, N.S.H.; Rockwood, D.; Tran Le, A.D. Studies on sustainable features of vernacular architecture in different regions across the world: A comprehensive synthesis and evaluation. Front. Archit. Res. 2019, 8, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Esparza, J.A. Vernacular Technologies and Vernacular Architecture. A Tendencies’ Review in Scholarly Publication Over the Last Twenty Years. In Building Engineering Facing the Challenges of the 21st Century. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Bienvenido-Huertas, D., Durán-Álvarez, J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; Volume 345, pp. 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, M.; Dipasquale, L.; Mecca, S. VerSus. Heritage for Tomorrow. Vernacular Knowledge for Sustainable Architecture; FUP: Firenze, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, P. Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World. 3 Volumes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bologna, R.; Hasanaj, G. Advanced Models For The Construction of An Nbs Catalogue For Resilience And Biodiversity. Agathón Int. J. Archit. Art Des. 2023, 13, 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Omelyanenko, O.; Vitaliy, A.O. Development of Community Infrastructure Based on the Local Resource-Based Approach. Her. Econ. Sci. Ukr. 2023, 1, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windhager, F.; Federico, P.; Schreder, G.; Glinka, K.; Dörk, M.; Miksch, S.; Mayr, E. Visualization of Cultural Heritage Collection Data: State of the Art and Future Challenges. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2019, 25, 2311–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heritage for People. Available online: https://heritageforpeople.unifi.it/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Mileto, C.; Vegas, F.; Correia, M.; Carlos, G.; Dipasquale, L.; Mecca, S.; Achenza, M.; Rakotomamonjy, B.; Sanchez, N. The European Project VerSus+/Heritage for People. Objectives and Methodology. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 44, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipasquale, L.; Mecca, S.; Montoni, L. Heritage for People. Sharing Vernacular Knowledge to Build the Future; DidaPress: Firenze, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea, A. Modelli GIS nel Cultural Resource Management. Archeol. E Calc. 2000, 11, 153–170. Available online: http://www.archcalc.cnr.it/indice/PDF11/1.10%20Dandrea.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Schauppenlehner, T.; Eder, R.; Ressar, K.; Feiglstorfer, H.; Meingast, R.; Ottner, F. A Citizen Science approach to build a knowledge base and cadastre on earth buildings in the Weinviertel region, Austria. Heritage 2021, 4, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.; Kingston, R.; Carver, S.; Turton, I. Web-based GIS to enhance public democratic involvement. In Proceedings of the Geocomp, Mary Washington College, Fredericksburg, VA, USA, 27–28 July 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaudo, F.; Agosto, E.; Ardissone, P. GIS and Web-GIS, Commercial and Open Source Platforms: General Rules for Cultural Heritage Documentation. In Proceedings of the XXI International CIPA Symposium, Athens, Greece, 1–6 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- García-Esparza, J.A.; Tena, P.A. A GIS-based methodology for the appraisal of historical, architectural, and social values in historic urban cores. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandreau, D.; Delboy, L. World Heritage: Inventory of Earthen Architecture; CRATerre-ENSAG: Grenoble 2012. Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2973/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Sigecweb. Available online: https://www.sigecweb.beniculturali.it/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Catalogo Generale dei Beni Culturali. Available online: https://catalogo.beniculturali.it/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Desiderio, M.L.; Mancinelli, M.L.; Negri, A.; Plances, E.; Saladini, L. Il SIGECweb nella prospettiva del catalogo nazionale dei beni culturali. DigItalia 2013, 8, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sosbrutalism. Available online: https://www.sosbrutalism.org/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Elser, O. SOS Brutalismus Ein Zwischenbericht. Die Denkmalpfl. 2019, 77, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmbau im Weinviertel. Citizen Science Projekt zu Lehmbau im Weinviertel. Available online: https://cs-lehmbau.boku.ac.at/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Hiberatlas. Historic Building Energy Retrofit Atlas. Available online: https://hiberatlas.eurac.edu/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Haas, F.; Herrera, D.; Hüttler, W.; Exner, D.; Troi, A. Historic Building Atlas: Sharing best practices to close the gap between research & practice. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Energy Efficiency in Historic Buildings (EEHB2018), Visby, Sweden, 26–27 September 2018; pp. 236–245. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10863/8802 (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Herrera-Avellanosa, D.; Rose, J.; Thomsen, K.E.; Haas, F.; Leijonhufvud, G.; Brostrom, T.; Troi, A. Evaluating the Implementation of Energy Retrofits in Historic Buildings: A Demonstration of the Energy Conservation Potential and Lessons Learned for Upscaling. Heritage 2018, 7, 997–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage Atlas Porto. Available online: https://heritageatlasporto.arq.up.pt/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Ferreira, T.C.; Ordóñez-Castañón, D.; Fernandes Póvoas, R. Methodological approach for an Atlas of architectural design in built heritage: Contributions of the School of Porto. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2023; ahead of online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapadaterra. Available online: https://mapadaterra.org/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Grappi, L.; Guerra, K. Mapadaterra platform. In Heritage for People; Dipasquale, L., Mecca, S., Montoni, L., Eds.; Didapress: Florence, Italy, 2023; p. 213. [Google Scholar]

- Mediterre Network. Available online: https://www.kisskissbankbank.com/en/projects/mediterre-un-site-internet-pour-le-reseau-de-la-construction-terre-mediterraneen (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Red Nacional de Maestros de la Construcción Tradicional. Available online: https://redmaestros.com/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- García Hermida, A. La Red Nacional de Maestros de la Construcción Tradicional. PH Boletín Del Inst. Andal. Del Patrim. Histórico 2019, 27, 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartoterra. Available online: www.cartoterra.net (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Paccoud, G.; Rakotomanokjy, B. Cartoterra, un atlas en ligne des architectures de terre, Poster #206. In Proceedings of the Terra 2016, XIIe Congrès Mondial Sur Les Architectures de Terre, Lyon, France, 11–14 July 2016; Available online: https://craterre.hypotheses.org/files/2016/10/206.jpg (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- MEA- Map of Earthen Architectures. Available online: https://www.terracruda.org/it/mappa-mea (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Kolodner, J. Case-Based Reasoning; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993; p. 668. [Google Scholar]

- Zambelli, M. La Conoscenza per il Progetto Il Case-Based Reasoning Nell’architettura e Nel Design; FUP: Florence, Italy, 2022; p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- Dipasquale, L.; Ammendola, A.; Ferrari, E.P.; Mecca, S.; Montoni, L.; Zambelli, M. A collaborative Web App to foster a knowledge network on vernacular heritage, craftspeople, and sustainability. In Proceedings of the HERITAGE 2022—International Conference on Vernacular Heritage: Culture, People and Sustainability, Valencia, Spain, 15–17 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sandesara, M.; Bodkhe, U.; Tanwar, S.; Alshehri, M.D.; Sharma, R.; Neagu, B.-C.; Grigoras, G.; Raboaca, M.S. Design and Experience of Mobile Applications: A Pilot Survey. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wever, R.; van Kuijk, J.; Boks, C. User-centred design for sustainable behaviour. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2008, 1, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, R.E.; Çöltekin, A.; Delazari, L.; Denney, B.; Mendonça, A.; Ricker, B.A.; Shen, J.; Stachoň, Z.; Wu, M. Making maps & visualizations for mobile devices: A research agenda for mobile-first and responsive cartographic design. J. Locat. Based Serv. 2024, 18, 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oordt, S.; Guzman, E. On the Role of User Feedback in Software Evolution: A Practitioners’ Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 29th International Requirements Engineering Conference (RE), Notre Dame, IN, USA, 20–24 September 2021; pp. 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchenaki, M. The Interdependency of Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 14th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, 27–31 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ginzarly, M.; Teller, J. Online communities and their contribution to local heritage knowledge. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 11, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sustainability Levels | Sustainability Principles | Sustainability Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Respecting nature and landscape |

|

| Taking benefit from natural and climatic resources |

| |

| Reducing pollution |

| |

| Ensuring human well-being and comfort |

| |

| Reducing disaster risks |

| |

| Socio-cultural | Preserving the cultural landscape |

|

| Transmitting and sharing building cultures |

| |

| Encouraging creativity |

| |

| Recognising intangible values |

| |

| Encouraging social cohesion |

| |

| Socio-economic | Supporting autonomy |

|

| Promoting local activities |

| |

| Optimising construction efforts |

| |

| Extending lifetime |

| |

| Saving resources |

|

| Question | Responses |

|---|---|

| Do you find the app useful? | Yes: 100% No: 0% |

| Share with us the most useful aspects | Most popular: Classification; Documentation; Mapping. Also prominent: Case studies; Find examples; Tags; Material section; Project database; References; Information; Knowledge. |

| Did you find any criticalities? | Most popular: Upload of images. Also prominent: Localisation; Link to extra material. |

| Any suggestions for improvement? | Most popular: Implementation of the map for localisation. Also prominent: Credits for each picture; expected time for uploading. |

| How did you find the process of adding features to the database? | Easy: 100% Not that easy: 0% |

| Are you going use/consult the app again? | Yes: 80% Probably: 20% No: 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dipasquale, L.; Ammendola, J.; Montoni, L.; Ferrari, E.P.; Zambelli, M. Harnessing Vernacular Knowledge for Contemporary Sustainable Design through a Collaborative Digital Platform. Heritage 2024, 7, 5251-5267. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090247

Dipasquale L, Ammendola J, Montoni L, Ferrari EP, Zambelli M. Harnessing Vernacular Knowledge for Contemporary Sustainable Design through a Collaborative Digital Platform. Heritage. 2024; 7(9):5251-5267. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090247

Chicago/Turabian StyleDipasquale, Letizia, Jacopo Ammendola, Lucia Montoni, Edoardo Paolo Ferrari, and Matteo Zambelli. 2024. "Harnessing Vernacular Knowledge for Contemporary Sustainable Design through a Collaborative Digital Platform" Heritage 7, no. 9: 5251-5267. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090247

APA StyleDipasquale, L., Ammendola, J., Montoni, L., Ferrari, E. P., & Zambelli, M. (2024). Harnessing Vernacular Knowledge for Contemporary Sustainable Design through a Collaborative Digital Platform. Heritage, 7(9), 5251-5267. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090247