Dunhuang Architectural Studies, 1926–2024

Abstract

:1. Introduction

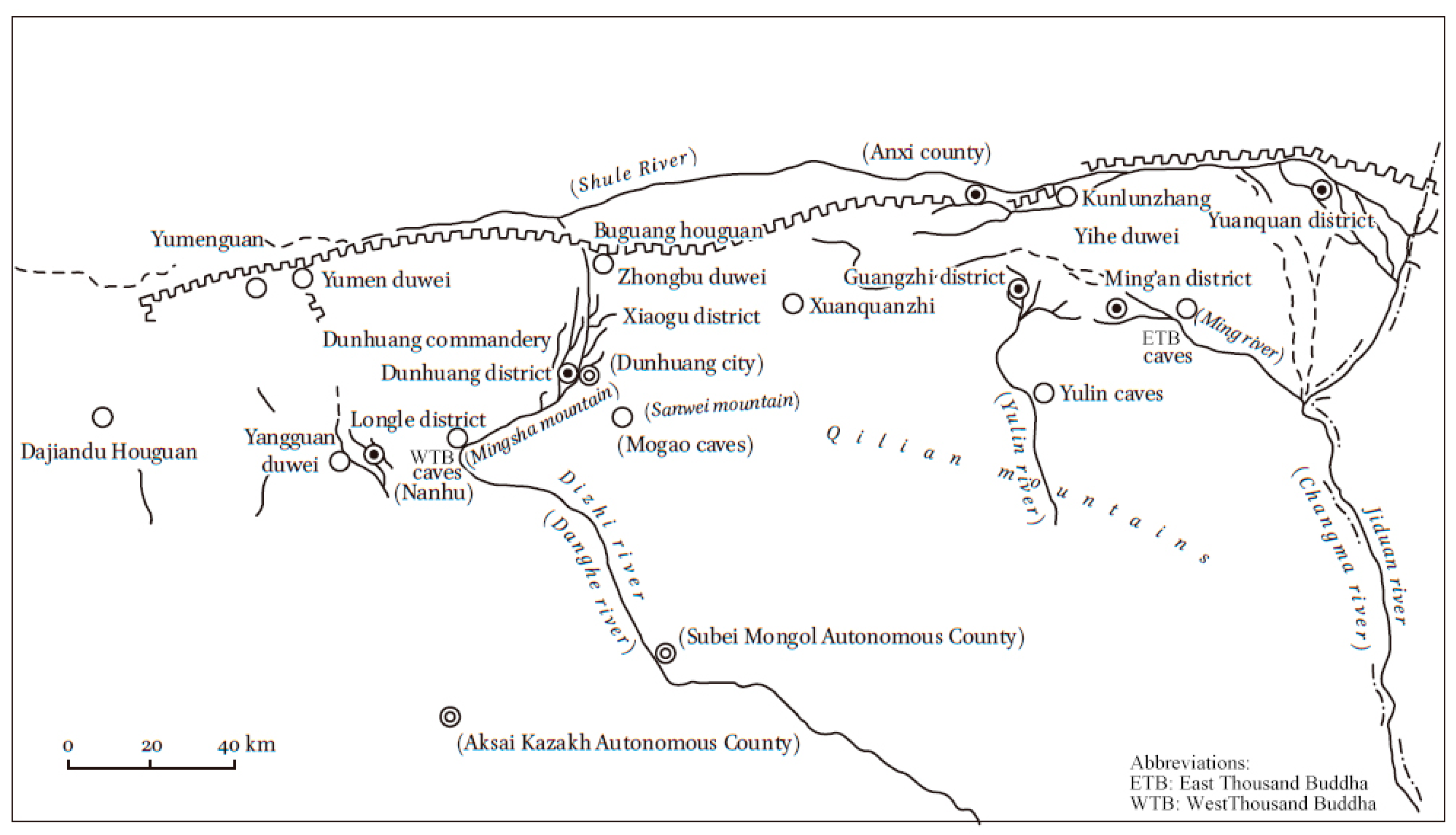

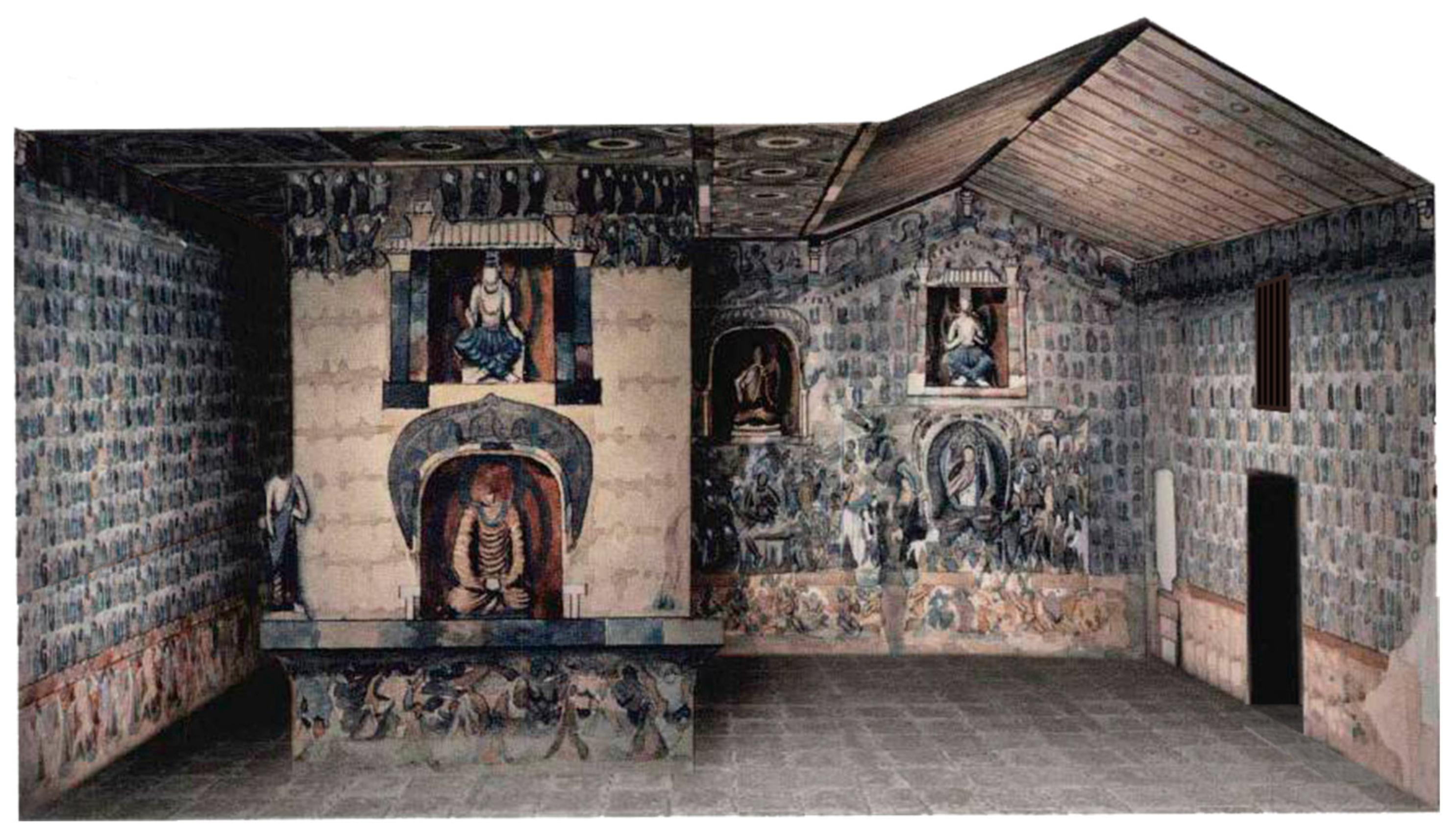

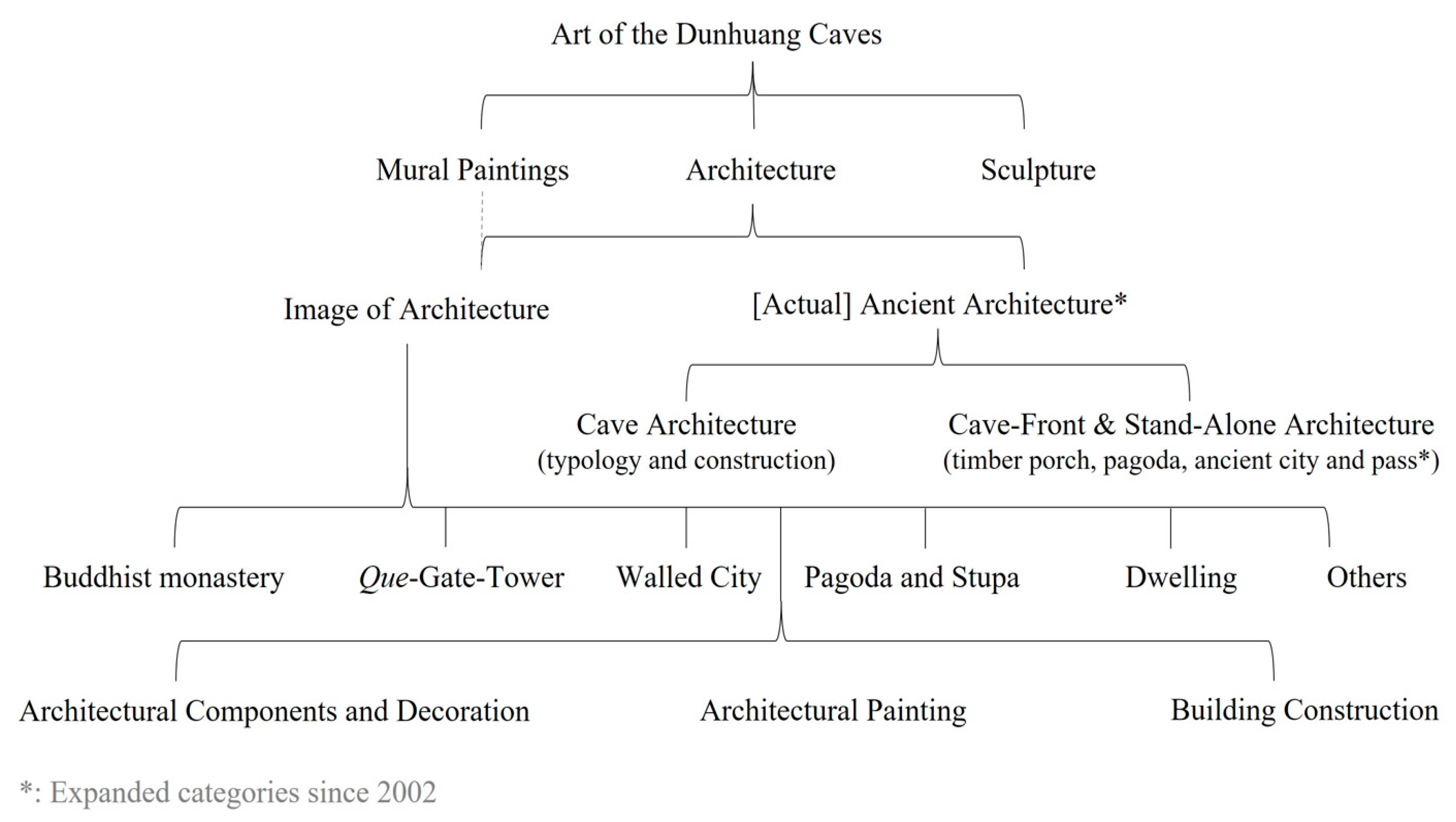

1.1. Scope: Pictorial and Actual Buildings from the Dunhuang Caves

1.2. Historical Accessibility and Assessments

1.3. Overview of the Field’s Developments and Inquiries

2. The First Phase (1926–1950): Early Exploration of Materials and Methods

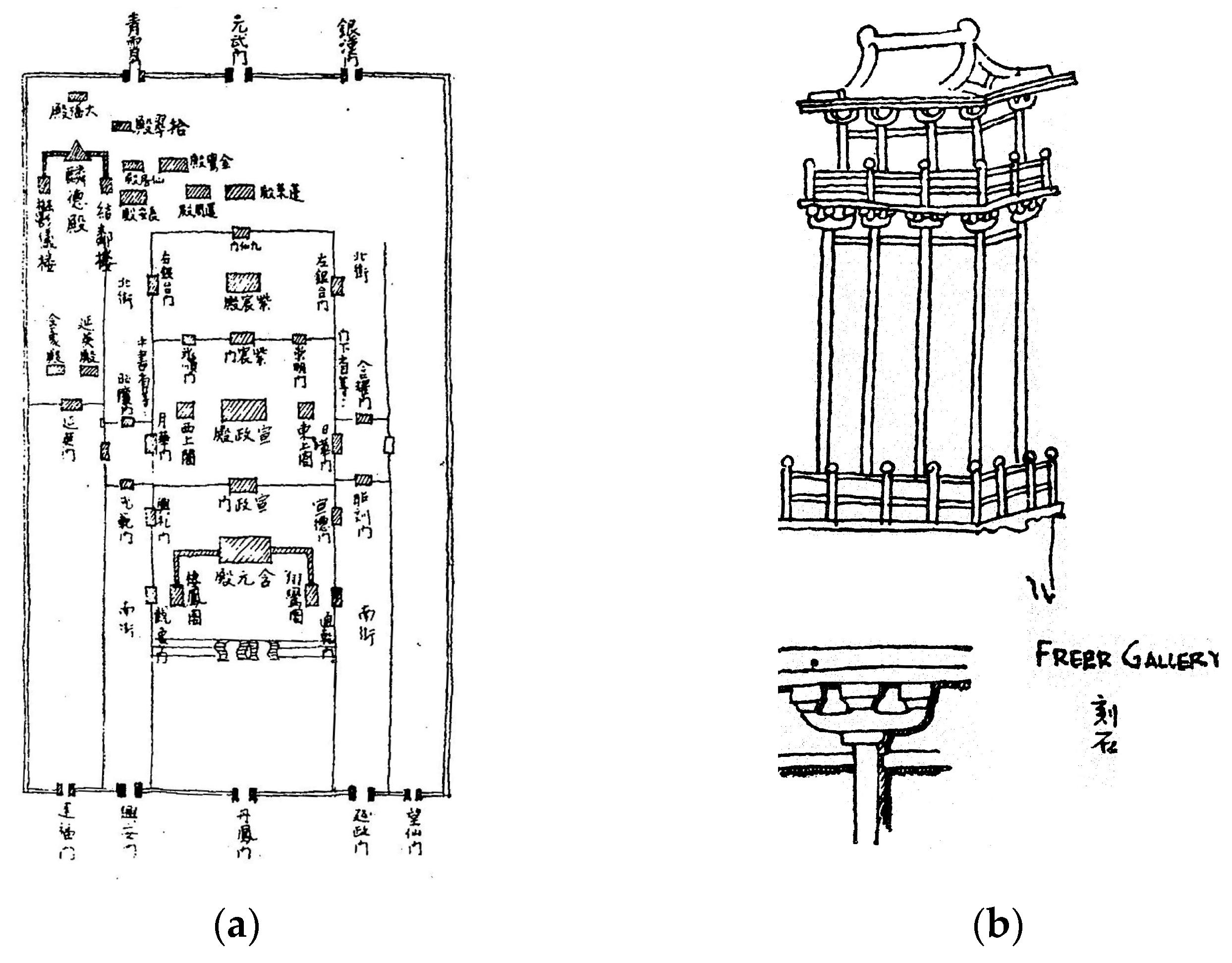

2.1. SRCA Scholarship Shaping the Discourse About Chinese Architectural History

2.2. An Art Historical Glimpse into Religious Visual Culture

3. The Second Phase (1950–2000): Taxonomy Versus Spatial Conception

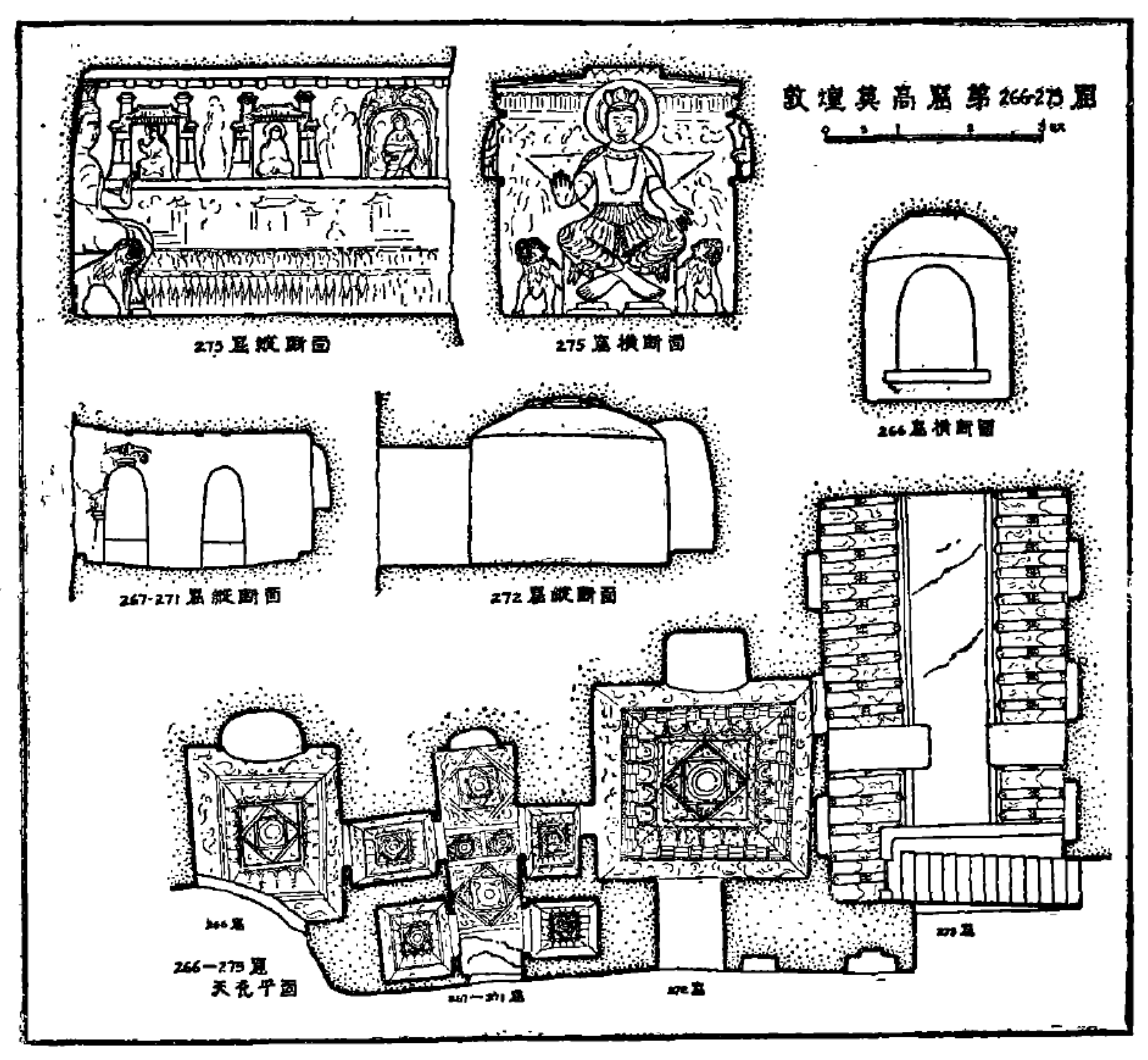

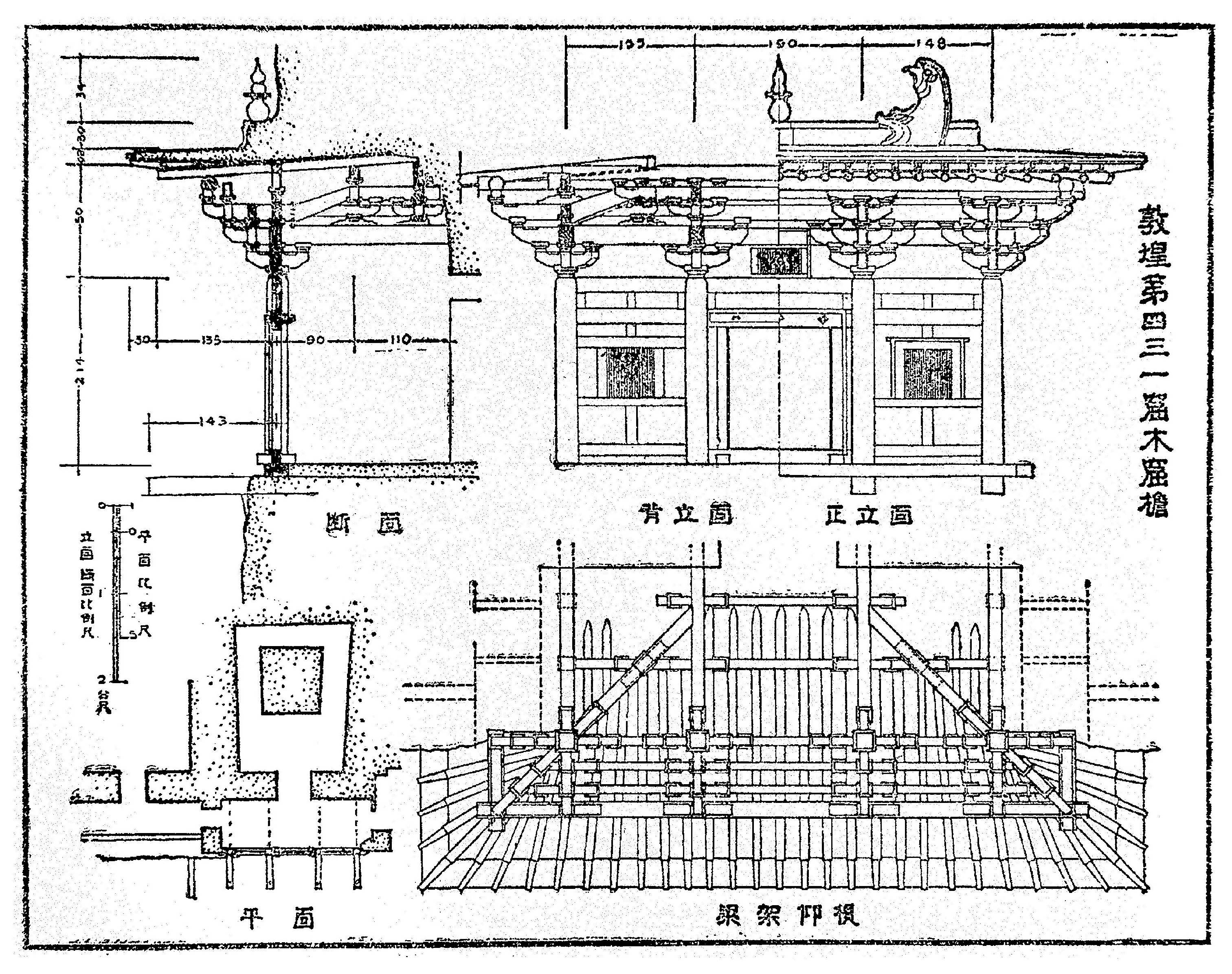

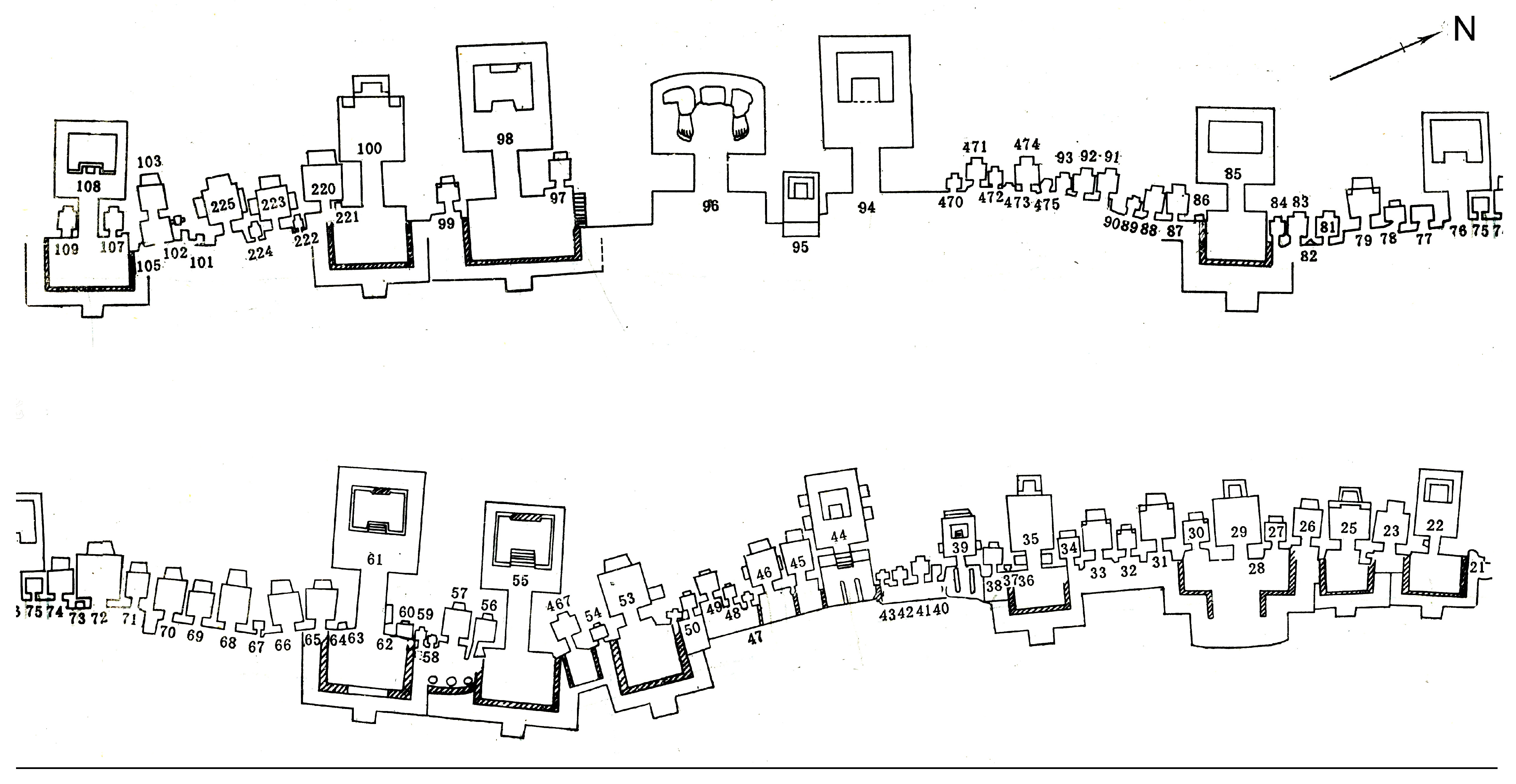

3.1. Archaeological Fieldwork and Knowledge About the Cave-Front Architecture

3.2. Establishment of a Comprehensive Research Framework

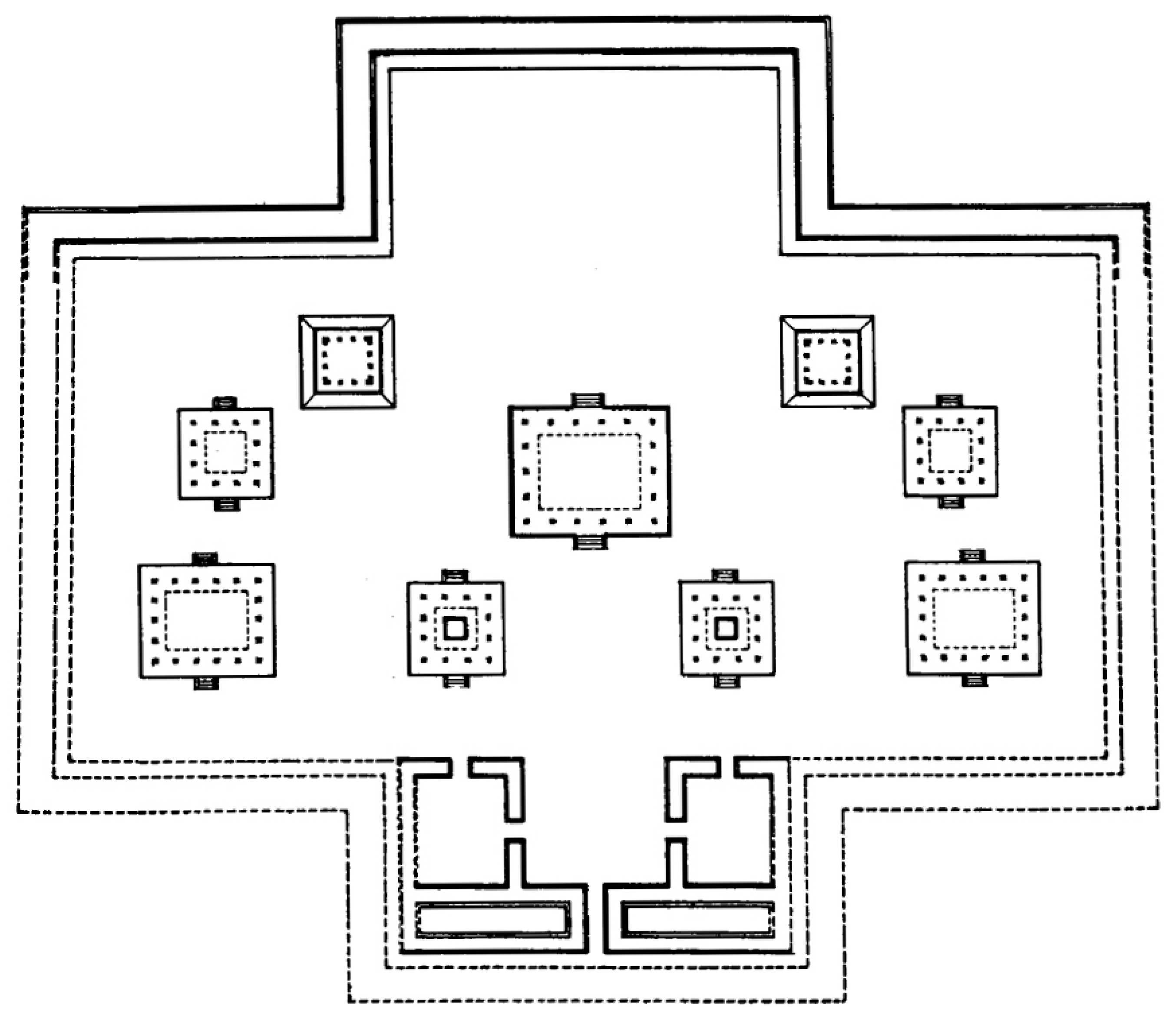

3.3. Visual Representation and Spatial Conceptions

3.4. Social History and the Production of Cave Space

3.5. Inquiries About the Relationships Between Image and Site, Cave and Stand-Alone Architecture

4. The Third Phase (Since 2001): New Materials, Perspectives, and Technologies

4.1. Blooming Publications, Correlated Visual Materials, and Surveys of Built Environment

4.2. Developments of Scholarship on Visual Representation of Architecture

4.3. A New Perspective: Space as an Analytic Tool

4.4. Digital Technologies for Research and Display

5. Reflections: Toward a Fuller Understanding of Space

5.1. Achievements and Limitations of Current Scholarship

5.2. Four Interrelated Aspects of Space

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Bulling earned a PhD degree from Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität (today, Humboldt University) in Berlin in 1936, and Boerschmann taught Chinese architecture in Berlin between 1924 and 1944 and lectured at the Institute of Art History at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität between 1938 and 1944. |

| 2 | Although many Dunhuang-based scholars, including Sun and Xiao, began to publish their studies no earlier than the late 1970s and early 1980s, many of the materials in their studies were collected in the 1950s–1960s. |

| 3 | Zhao, Mo, and Chen were SRCA members who had engaged in surveys of Chinese architectural heritage since the foundation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. |

| 4 | The Guiyijun Circuit (歸義軍, lit. returning to righteousness army) is a tributary state of the Tang Empire and its successors. When Dunhuang was a seat of the Guiyijun regime, the secular and monastic leaders of this regime commissioned quite a few monumental cave temples at the Mogao site. |

| 5 | As Xiao suggests, the image or architecture containing content that is prescribed by Buddhist scriptures is more idealized than their prototypes in real life and is constrained by the traditional methods of representing three-dimensional forms in paintings. Therefore, Xiao usually justifies the validity of the image of architecture by comparing it with historical texts, archaeological findings, or comparative cases in East Asia. |

| 6 | For instance, Xiao sees the central-altar cave without a backscreen as a variant of the upturned-funnel cave type, but most archaeologists and non-architectural specialists see the backscreen-less cave and the backscreened cave as two variants of the central-altar cave type. Furthermore, Xiao negates the possible connection between the central-altar cave and the central-pillar cave, whereas some other scholars found the architectural vocabularies of the central-altar cave in both the central-pillar cave and the upturned-funnel cave. |

| 7 | Earlier studies of Dunhuang murals of architecture, such as those by Liang Sicheng, Bulling, and Su Bai, also included trace-copy line drawings of visual details in a mural, such as pavilions, pagodas, bracket sets, and railings. But Xiao was the first one to trace-copy the architecture in an entire painting composition. Accordingly, the more ambitious way of trace-copying raised new issues of visual composition, spatial representation, and the relationship between architectural and figural elements in the painting. |

| 8 | In the 1950s–1970s, religious art was generally accepted to be a kind of “spiritual opium” that the dominant class imposed on the subordinate class by the Chinese intellectuals. Although the role of the artisans—who represent the “working class” in premodern China—in the production of the Dunhuang Buddhist art received positive acknowledgment, the works of art were considered to be counterrevolutionary. |

| 9 | Giedion proposed a three-phased development of space in Western architecture: architecture as space-radiating volumes, as interior space, and as both volume and interior space. In comparison, Inoue proposed a four-stage development of space in Japanese architecture: preeminence of the material object, plastic composition and pictorial composition, interior space, and from geometric space to movement space. |

| 10 | Xiao first studied the flower pagoda and pointed out the similarity between the bracket set of the flower pagoda and those depicted in Tang-period Dunhuang murals, but the recognition of overall pagoda form, especially the distinctive lotus-flower-like finial, is a further step. |

| 11 | For instance, in addition to being cited in scholarly works, the rendering of the Mogao cliff face has been reproduced and displayed in exhibitions in China in the 2020s. |

| 12 | The examination of the plastic representation of architecture in the Chinese caves began in the first decade of the twentieth century, as exemplified by Japanese scholar Ito Chuta’s examination of the Yungang grottoes [129,130], but the systematic studies of various kinds of representation occurred after these kinds of materials had been surveyed and studied. |

| 13 | The concept of a “representative cave” has existed since the Dunhuang Institute began to present selective works of art of Dunhuang in exhibitions and photo albums. But rather than focusing on the period style and artistic quality as the “representative cave” indicates, the term originary cave denotes the consideration of the degrees of convention and innovation that occurred in a cave design. |

| 14 | Researchers have been using the drawing and 3D modeling software that has been widely applied in architectural design, such as AutoCAD, Sketchup, Rhinoceros, and Autodesk Revit Architecture, for trace-copy and spatial reconstruction of architectural images. |

| 15 | 3D printing has been applied to replicate polychromic statues of Dunhuang and to turn digital reconstructions of the images of architecture into physical models. For examples of the latter, see the exhibition A Thousand Years of Construction: The Beauty of Dunhuang Architecture at the Exhibition Center of Dunhuang Academy since May 2022. |

| 16 | The cave makers include Buddhist priests and institutes, fundraisers, patrons, and artisans. Cave makers may adopt one or more identities. |

| 17 | This approach is exemplified by archaeologist Giuseppe Vignato’s long-term studies of the Kuchan caves. His recent monograph, in collaboration with art historian Satomi Hiyama, systematically examines the natural and built environments with the concept of “the sense of place” [162]. |

References

- Liang, S. Boxihe xiansheng guanyu Dunhuang jianzhu de yifeng xin 伯希和先生關於燉煌建築的一封信 [A letter from professor Paul Pelliot to Liang Ssu-ch’eng]. Zhongguo Yingzao Xueshe Huikan 中國營造學社彙刊 [Bull. Soc. Res. Chin. Archit.] 1932, 3, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S. Women suo zhidao de tangdai fosi yu gongdian 我們所知道的唐代佛寺與宮殿 [Buddhist temples and palaces of the Tang dynasty that we know]. Zhongguo Yingzao Xueshe Huikan 1932, 3, 75–114. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S. Dunhuang bihua zhong suo jian zhongguo gudai jianzhu 敦煌壁畫中所見中國古代建築 [Chinese traditional architecture seen in the Dunhuang wall paintings]. Wewu Cankao Ziliao 文物參考資料 [Cult. Relics] 1951, 5, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M. Dunhuang Jianzhu Yanjiu 敦煌建築研究 [A study of Dunhuang Architecture]; Cultural Relics Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Zhao, S. Dunhuang Yishu Da Cidian 敦煌藝術大辭典 [Encyclopedia of Dunhuang Art]; Dunhuang Yanjiu Yuan 敦煌研究院 [Dunhuang Academy], Ed.; Shanghai Cishu Chuban She: Shanghai, China, 2019; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M. Dunhuang Jianzhu Yanjiu, 3rd ed.; Zhongguo Jianzhu Gongye Chuban She: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, N.; Reed, M.; Tevvy Ball, T.; Getty Conservation Institute; Getty Research Institute; Dunhuang Academy. Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, X. Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang. Galambos, I., Translator; Brill: Leiden, Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R.; Sun, Y. Dunhuang Shiku Quanji 21: Jianzhu Hua Juan 敦煌石窟全集 21: 建築畫卷 [Comprehensive Collection of the Dunhuang Grottoes: Volume 21 on Architectural Painting]; Shangwu Yinshu Guan: Hong Kong, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Sun, R. Dunhuang Shiku Quanji 22: Shiku Jianzhu Juan 敦煌石窟全集 22: 石窟建築卷 [Comprehensive Collection of the Dunhuang Grottoes: Volume 22 on Cave Architecture]; Shangwu Yinshu Guan: Hong Kong, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang shi zhi bianzhuan weiyuan hui 敦煌市志編撰委員會 [Editing committee of the gazetteer of Dunhuang City] (Ed.) Dunhuang Shi Zhi 敦煌市志 [Gazetteer of Dunhuang City, abbreviated as DHSZ]; Xinhua Chuban She: Beijing, China, 1994; pp. 262–268. [Google Scholar]

- Pelliot, P. Les grottes de Touen-houang: Peintures et sculptures Boudhiques des epoques des Wei, des Tang et des Song 1914–1924; Paul Geithner: Paris, France, 1924; 6 Volumes. [Google Scholar]

- Gosudarstvennyi Ermitazh [Russia] 俄羅斯國立艾爾米塔什博物館; Dunhuang Academy; Shanghai Publishing House of Traditional Books [Shanghai guji chuban she 上海古籍出版社] (Eds.) Eluosi Guo Li Ai’ermitashi Bo Wu Guan Cang Dunhuang Yi Shu Pin 1997–2005 俄羅斯國立艾爾米塔什博物館藏敦煌藝術品 1997–2005 [Dunhuang Art Collection in the State Hermitage Museum of Russia 1997–2005]; Shanghai Publishing House of Traditional Books: Shanghai, China, 2005; 6 Volumes. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, C.-J. Mogao Ku Xing 莫高窟形 [The Shape of the Mogao Caves]; Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica: Taipei, China, 1996; 3 Volumes. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, N.S. Chinese Architecture: A History; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S. A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture: A Study of the Development of Its Structural System and the Evolution of Its Types; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, N.S. Standard Architecture in a Multi-centered Multi-cultural Age. In Tenth-Century China and Beyond: Art and Visual Culture in a Multi-Centered Age; Wu, H., Ed.; The Center for the Art of East Asia, Department of Art History, University of Chicago, and Art Media Resources: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012; pp. 38–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, L. Vision and Site: Revisiting a Pure Land Cave of Dunhuang. Religions 2024, 15, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K. Hōryūji no kenchiku yōshiki to Shina Rikuchō no kenchiku yōshiki ni tsuite 法隆寺の建築様式と支那六朝の建築様式に就いて” [On the architectural style of Horyuji Temple and the architectural style of the Six Dynasties in China]. In Naitō Hakushi Kanreki Shukuga Shināgaku Ronsō 內藤博士還暦祝賀支那學論叢 [Dr. Naito’s Sixtieth Birthday Commemoration: Essay Collections on China Studies]; Naitō, T., Haneda, T., Eds.; Kōbundō Shobō: Kyōto, Japan, 1926; pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X. Understanding Chinese Research Work on Architectural History. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 2014, 73, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Ecke, G. The Institute for Research in Chinese Architecture 中國營造辜勝: A Short Summary of the Field Work Carried on from Spring 1932 to Spring 1937. Monum. Serica 1937, 2, 448–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K.; Liu, D. Falong si yu han liuchao jianzhu shiyang zhi guanxi 法隆寺與漢六朝建築式樣之關係 [Horyuji and the architecture of the Han and Six Dynasties in China]. Zhongguo Yingzao Xueshe Huikan 1932, 3, 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bulling, A. Die chinesische Architektur von der Han-Zeit biszum Ende der T’ang-Zeit. Ph.D. Dissertation, Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- J. B. Reviewed Work: Die Chinesische Architektur von der Han-Zeit bis zum Ende der T’ang-Zeit. Rev. Des Arts Asiat. 1936, 10, 229.

- Liu, D. Cong lishi tuxiang dao jianzhu xinxi: Yi 1930–1950 niandai liangwei xuezhe yi Dunhuang bihua wei sucai de jianzhu shi yanjiu chengguo wei li 從歷史圖像到建築資訊—以1930–1950年代兩位學者以敦煌壁畫為素材的建築史研究成果為例 [From historical images to architectural information research of architectural history on Dunhuang frescoes by two scholars from the 1930s to the 1950s]. Jianzhu Xuebao 2014, 9–10, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bulling, A. Buddhist Temples in T’ang Period, Part I. Oriental Art 1955, 1, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bulling, A. Buddhist Temples in T’ang Period, Part II. Oriental Art 1955, 1, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kögel, E. The Grand Documentation: Ernst Boerschmann and Chinese Religious Architecture (1906–1931); De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boerschmann, E. P’u t’o shan: Die heilige Insel der Kuan yin, der Göttin der Barmherzigkeit; Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer: Berlin, Germany, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Kögel, E. Early German Research in Ancient Chinese Architecture (1900–1930). Berl. Chinahefte Chin. Hist. Soc. 2011, 39, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Prip-Møller, J. Preface. In Chinese Buddhist Monasteries: Their Plan and Its Function as a Setting for Buddhist Monastic Life; G.E.C. Gad: Copenhagen, Danmark; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z. Transcending History: (Re)Building Longchang Monastery of Mount Baohua in the Seventeenth Century. Religions 2022, 13, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Dunhuang Mogao Ku Jingtu Bian Jianzhu Tuxiang Yanjiu 敦煌莫高窟淨土變建築圖像研究 [A Study of the Architectural Images in Pure Land Illustrations of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves]. Ph.D. Dissertation, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, S.E. Buddhist Archaeology in Republican China: A New Relationship to the Past. Proc. Br. Acad. 2011, 167, 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Artstor, Mellon International Dunhuang Archive (MIDA). Available online: https://www.artstor.org/collection/mellon-international-dunhuang-archive/ (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Ching, D.C.Y. (Ed.) Visualizing Dunhuang: Seeing, Studying, and Conserving the Caves; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, C.-J. Huabei shiku de shidaixing yu diyu xing 華北石窟的時代性和地域性 [The epochal and the regional characteristics of cave-temples in northern China]. Zhongyang Yanjiu Yuan Lishi Yuyan Yanjiu Suo Jikan 中央研究院歷史語言研究所集刊 [Bull. Inst. Hist. Philol. Acad. Sin.] 1957, 29, 545–612. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, C.-J. Dunhuang mogaoku wantang ku de fenxi yu yanjiu 敦煌莫高窟晚唐窟的分析與研究 [An analytical study of the late-Tang Dunhuang Mogao caves]. Hanxue Yanjiu 漢學研究 [Chin. Stud.] 1993, 11, 259–323. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J. Dunhuang shiku kaogu bainian huigu 敦煌石窟考古研究百年回望 [Review of the century of archaeological studies of the Dunhuang caves]. In Woxin Guichu Shi Dunhuang: Fan Jinshi Zishu 我心歸處是敦煌: 樊錦詩自述 [My Heart Takes Home in Dunhuang: Oral Autobiography of Fan Jinshi]; Fan, J., Gu, C., Eds.; Xianggang Zhonghe Chuban Youxian Gongsi: Hong Kong, China, 2020; pp. 399–409. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R.; Qi, S.; Yang, X. Puti Shuxia 菩提樹下 [Under the Bodhi Tree]; Zhongguo Qingnian Chuban She: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M. Yi Ye Yi Puti: Wo Zai Dunhuang Shiwu Nian 一葉一菩提: 我在敦煌十五年 [One Leaf for a Bodhi in a Leaf: My Fifteen Years in Dunhuang]; Xinxing Chuban She: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, Z.; Mo, Z.; Su, B.; Yu, M. Dunhuang shiku kancha baogao 敦煌石窟勘察報告 [Survey report about the Dunhuang caves]. Wenwu Cankao Ziliao 1955, 2, 39–70, pls. 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Chen Mingda Quanji 2: Gudai Diaosu Yu Shiku Yishu Yanjiu 陳明達全集 2: 古代雕塑與石窟藝術研究 [Comprehensive Collection of Chen Mingda 2: Studies of Ancient Sculpture and Cave Art]; Zhejiang Photography Publishing House: Hangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Dunhuang fujin de gujianzhu: Chengcheng wan tuta ji laojun tang cishi zhi ta 敦煌附近的古建築: 成城灣土塔及老君堂慈氏之塔 [Ancient buildings near Dunhuang: An earthen pagoda at Chengcheng bent and the Pagoda of Maitreya near Laojun hall]. Wenwu Cankao Ziliao 1955, 2, 109–110. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M. Dunhuang Mogao ku fujin de liangzuo Song ta 敦煌莫高窟附近的兩座宋塔 [Two Song-period pagodas near the Dunhuang Mogao caves]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 1983, 3, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M. Zhongguo shikusi kuqian jianzhu de faxian yu yanjiu 中國石窟寺窟前建築的發現與研究 [Discoveries and studies of the cave-front architecture of Chinese caves]. Zhongguo Wenhua Yichan 中國文化遺產 2018, 5, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Ma, S. Mogaoku kuqian diantang yizhi 莫高窟窟前殿堂遺址 [Ruins of Frontal Buildings Added to Mogao Grottoes]; Wenwu Chuban She: Beijing, China, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, W. Dunhuang Mogao ku di 72–76 ku kuqian diantang yizhi qingli fajue baogao 敦煌莫高窟第72–76窟窟前殿堂遺址清理發掘報告 [Report of the archaeological excavation of the front-hall remnants of Dunhuang Mogao Cave 72–76]. Kaogu Xuebao 2002, 4, 493–513. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Wang, J.; Guo, J. Dunhuang mogao ku jiucenglou laogu xin faxian 敦煌莫萵窟‘九層樓’考古新發現 [New archaeological discoveries of the “nine-story pavilion” of Dunhuang Mogao caves]. In 2000 Nian Dunhuang Xue Guoji Xueshu Taolun Hui Lunwen Tiyao Ji 2000年敦煌學國際學術討論會論文提要集 [Collections of the Paper Abstracts of the International Conference on Dunhuang Studies in 2000]; Dunhuang Acedemy, Ed.; Dunhuang Academy: Dunhuang, China, 2000; pp. 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. Dunhuang shiku laba randeng fenpei kukan mingshu 敦煌石窟臘八燃燈分配窟龕名數 [List of caves for distributing lanterns during the light up on the eighth day of the twelve month]. Wenwu 1959, 5, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D. Jiuzhou daxue wenxue bu cang Dunhuang wenshu ‘xin dade zao kuyan jiliao’ tanwei 九州大學文學部藏敦煌文書《新大德造窟簷計料》探微 [A preliminary study of records about building materials used by the new Bhadanta in rebuilding the eaves of a cave of Dunhuang manuscript kept in the Literary Department of Kyūshū University]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 1993, 3, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Q. Dunhuang shiku songchu kuyan ji beiwei dong neidougong shulue 敦煌石窟宋初窟簷及北魏洞內斗拱述略 [Brief discussion of the early-Song cave eaves and the Northern-Wei bracket-sets inside the caves at the Dunhuang caves]. Tumu Jianzhu Yu Huanjing Gongcheng 土木建築與環境工程 [J. Chongqing Jianzhu Univ.] 1957, 1, 51–75. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M. Mogao ku di 196 kuyan yanjiu 莫高窟第196窟簷研究 [A study of the timber-structured façade of Mogao Cave 196]. In Keji Shi Wenji 7: Jianzhu Shi Zhuanji 科技史文集7: 建築史專輯 [Essay Collections About the History of Science 7: Volume on Architectural History]; Jianzhu Shi Zhuanji Bianji Weiyuan Hui 建築史專輯編輯委員會 [Editing Committee of the Volume on Architectural History], Ed.; Shagnhai Kexue Jishu Chuban She: Shanghai, China, 1981; pp. 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M. Dunhuang Mogaoku di 53 ku kuqian Song dai jianzhu fuyuan 敦煌莫高窟第53窟窟前宋代建築復原 [Theoretical reconstruction of a Song-period building in front of Mogao Cave 53 of Dunhuang]. Kaogu 1977, 6, 412–421. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. Mogao ku 55 ku kuqian jianzhu fuyuan yanjiu 莫高窟55窟窟前建築復原研究 [Reconstructional study of the frontal architecture of Mogao Cave 55]. Jianzhu shi 2018, 2, 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J. Riben Jiuzhou daxue cang Dunhuang wenshu suoji kuyan de fenxi yu fuyuan 日本九州大學藏敦煌文書所記窟簷的分析與復原 [A reconstruction and analysis of the grotto wood eaves recorded in the Dunhuang document collected at Kyūshū University, Japan]. Wenwu 1993, 12, 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W. Dunhuang kukan mingshu kao 敦煌窟龕名數考 [Study of the list of caves of Dunhuang]. Wenwu 1959, 5, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D. 10 shiji zhongqi de mogaoku yamian gaiguan—Guanyu ‘laba randeng fenpei kukan mingshu de jige wenti 10 世紀中期的莫高窟崖面概觀—關於<臘八燃燈分配窟龕名數>的幾個問題 [Overview of the Mogao cliff surface in the mid-tenth century—Several question about the manuscript titled “List of Caves for Distributing Lanterns during the Light up on the Eighth Day of the Twelve Month”]. In 1987 Nian Dunhuang Shiku Yanjiu Guoji Taolunhui Wen Ji: Shiku Kaogu Bian 1987年敦煌石窟研究國際討論會文集·石窟考古編 [Proceedings of the International Conference on Dunhuang Cave Studies in 1987]; Dunhuang Academy, Ed.; Liaoning Meishu Chubanshe: Shenyang, China, 1990; pp. 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D. Dunhuang Shiku Yingzao Shi Daolun 敦煌石窟營造史導論 [A Guide to the Construction History of the Dunhuang Caves]; Xinwenfeng Chuban Gufen Youxian Gongsi: Taipei, China, 2003; pp. 118–150. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y. Mogao ku waimao bianqian de jige wenti 莫高窟外貌變遷的幾個問題 [Several problems about the changes of the appearance of the Mogao caves]. In 1987 Nian Dunhuang Shiku Yanjiu Guoji Taolunhui Wen Ji: Shiku Kaogu Bian 1987年敦煌石窟研究國際討論會文集·石窟考古編 [Proceedings of the International Conference on Dunhuang Cave Studies in 1987]; Dunhuang Academy, Ed.; Liaoning Meishu Chubanshe: Shenyang, China, 1990; pp. 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M. Mogao ku bihua zhong de fosi 莫高窟壁畫中的佛寺 [Buddhist monasteries in Dunhuang mural paintings]. In Zhongguo Shiku: Dunhuang Mogao Ku 中國石窟: 敦煌莫高窟 [Chinese Caves Series: Dunhuang Mogao Caves]; Dunhuang Yanjiu Yuan, Ed.; Wenwu Chuban She: Beijing, China; Heibonsha: Tokyo, Japan, 1982; Volume 4, pp. 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M. Dunhuang Mogao ku de dongku xingzhi 敦煌莫高窟的洞窟形制 [The cave typology of the Mogao grottoes of Dunhuang]. In Zhongguo Shiku: Dunhuang Mogao Ku 中國石窟: 敦煌莫高窟 [Chinese Caves Series: Dunhuang Mogao Caves]; Dunhuang Yanjiu Yuan, Ed.; Wenwu Chuban She: Beijing, China; Heibonsha: Tokyo, Japan, 1982; Volume 2, pp. 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M. Mogao ku de Tang Song kuyan 莫高窟的唐宋窟簷 [Cave porches of the Tang and Song periods at the Mogao Caves] (unpublished paper written before 1981).

- Lin, W.-C. Building a Sacred Mountain: The Buddhist Architecture of China’s Mount Wutai; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J. Mogao ku qianqi shiku de dongku xingzhi he ticai bujv (zhaiyao) 莫高窟前期石窟的洞窟形制和題材佈局 (摘要) [Cave typology and iconographical distribution in the Mogao caves of the former periods (abstract)]. Dunhunag Yanjiu 1988, 15, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Su, B. Zhongguo Shiku Si Yanjiu 中國石窟寺研究 [Studies of Chinese Caves]; Wenwu Chuban She: Beijing, China, 1996; pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J. The Caves of Dunhuang; Dunhuang Academy in collaboration with London Editions: Hong Kong, China, 2010; pp. 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P-P. Chinese Monastic Buddhist Architecture in the Sui and Tang Dynasties: A Study of the Spatial Conception. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of London (SOAS), London, UK, 1992.

- Ledderose, L. Jingtu bian jianzhu de laiyuan (zhaiyao) 净土变建筑的来源 (摘要) [Origins of the architecture in pure land transformation tableaux (abstract)]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 1988, 2, 98–99, 129–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.-P. Paradise on Earth: Architectural Depictions in Pure Land Illustrations of High Tang Caves at Dunhuang. Orient. Art 1995, 41, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D. Yidai zunshi xuejie kaimo: Shi Weixiang xiansheng de xianshen jingshen yu xueshu chengjiu 一代尊師 學界楷模——史葦湘先生的獻身精神與學術成就 [Master of a generation, model of an academic field: Self-sacrifice and academic accomplishments of Shi Weixiang]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 2000, 65, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang Academy (Ed.) 1983 Nian Quanguo Dunhuang Xueshu Taolunhui Wenji 一九八三年全國敦煌學術討論會文集 [Proceedings of the Domestic Conference on Dunhuang Studies in 1983]; Gansu Renmin Chuban She: Lanzhou, China, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang Academy (Ed.) 1987 Nian Dunhuang Shiku Yanjiu Guoji Yantao Hui Lunwen Ji 1987年敦煌石窟研究國際討論會文集 [Proceedings of the International Conference on Studies of the Dunhuang Caves in 1987]; Liaoning Meishu Chuban She: Shenyang, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W. Zailun chansheng Dunhuang fojiao yishu de shehui yinsu 再論產生敦煌佛教藝術的社會因素 [A revisit of the social factors in the production of Dunhuang Buddhist art]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 1989, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W. Zailun chansheng Dunhuang fojiao yishu de shehui yinsu 3; Shi, Lun Dunhuang fojiao yishu de xiangxiangli 論敦煌佛教藝術的想像力 [On the Imagination of Dunhuang Buddhist art]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 1986, 9, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W. Lue lun dunhuang wantang yishu de shisu hua 略論敦煌晚唐藝術的世俗化 [A brief discussion of the secularization of late-Tang Dunhuang art]. In Dunhuang Shiku Yishu: Mogao Ku Di 9, 12 Ku 敦煌石窟藝術: 莫高窟第9、12窟 [Art of the Dunhuang caves: Mogao Caves 9 and 12]; Dunhuang Academy, Ed.; Jiangsu Meishu Chubanshe: Nanjing, China, 1999; pp. 10–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B. Dunhuang de huahang yu huayuan 敦煌的畫行與畫院 [Painting profession and painting academy of Dunhuang]. In 1983 Nian Quanguo Dunhuang Xueshu Taolunhui Wenji Shiku Yishubian 一九八三年全國敦煌學術討論會文集石窟藝術編 [Proceedings of the Domestic Conference on Dunhuang Studies in 1983: Volume on Cave Art]; Dunhuang Academy, Ed.; Gansu renmin chuban she: Lanzhou, China, 1985; Volume 2, pp. 172–191. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D. Caoshi sandaku yingjian de shehui beijing 曹氏三大窟營建的社會背景 [Social contexts of the construction of the three grand caves of the Cao clan]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 1991, 26, 18–24+114. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D. Dunhuang Mogao Ku Shi Yanjiu 敦煌莫高窟史硏究 [Study on the History of the Mogao Grottoes of Dunhuang]; Gansu Jiaoyu Chuban She: Lanzhou, China, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.; Zheng, Y. Dunhuang Bei Ming Zan Jishi 敦煌碑銘贊輯釋 [Annotated Collection of the Stelae, Epitaphs, and Eulogies of Dunhuang]; Shanghai Guji Chuban She: Shanghai, China, 2019; 3 Volumes. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W. Lun Dunhuang fojiao yishu de shisuxing: Jianlun ‘jingang jingbian’ zai Mogao ku de chuxian yu xiaoshi 論敦煌佛教藝術的世俗性—兼論<金剛經變>在莫高窟的出現與消失 [On the secular character of Dunhuang Buddhist Art: The appearance and disappearance of the Diamond Sūtra transformation tableaux in the Mogao caves]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 1985, 5, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W. Shizu yu shiku 氏族與石窟 [Clans and caves]. In Dunhuang Yanjiu Wenji 敦煌研究文集 [Essay Collections in Dunhuang Studies]; Dunhuang Cultural Relics Research Institute, Ed.; Gansu Renmin Chuban She: Lanzhou, China, 1982; pp. 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D. Dunhuang de shizu yu Mogao ku 敦煌的世族與莫高窟 [Clans in Dunhuang and the Mogao caves]. Dunhuang Xue Jikan 敦煌學輯刊 [J. Dunhuang Stud.] 1995, 28, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Q. Art, Religion, and Politics in Medieval China: The Dunhuang Cave of the Zhai Family; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Giedion, S. Architecture and the Phenomena of Transition: The Three Space Conceptions in Architecture; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Giedion, S. The Eternal Present: A Contribution on Constancy and Change; Bollingen Foundation; Pantheon Books: New York, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, M. Nihon Kenchiku no Kukan 日本建築の空間 [Space in Japanese Architecture]; Kajima Shuppankai: Tokyo, Japan, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, M. Space in Japanese Architecture; Watanabe, H., Translator; Weatherhill: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.-C. What Did Architecture Do in Visualizing Dunhuang? In Visualizing Dunhuang: The Lo Archive Photos of the Mogao and Yulin Caves; Ching, D.C.Y., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 9, p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Cai, W. Xiangmo bianwen yu unhuang bihua zhong de Laoducha doushengbian 降魔變文與敦煌壁畫中的牢度叉鬥聖變 [The subjugation transformation text and the subjugation transformation tableau in Dunhuang murals]. In 1983 Nian Quanguo Dunhuang Xueshu Taolunhui Wenji Shiku Yishubian 一九八三年全國敦煌學術討論會文集石窟藝術編 [Proceedings of the Domestic Conference on Dunhuang Studies in 1983: Volume on Cave Art]; Dunhuang Academy, Ed.; Gansu Renmin Chuban She: Lanzhou, China, 1985; Volume 1, pp. 187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. What Is Bianxiang?—On the Relationship between Dunhuang Art and Dunhuang Literature. Harv. J. Asiat. Stud. 1992, 52, 133–134. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D. Tang Houqi Wudai Songchu Dunhuang Sengsi Yanjiu 唐後期五代宋初敦煌僧寺研究 [A Study of the Buddhist Monasteries in Dunhuang of the Late-Tang, Five Dynasties, and Early-Song Periods]. Ph.D. Dissertation, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2008; pp. 136–166. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, A.C. The Evolution of Buddhist Architecture in Japan. Ph.D. Dissertation, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA, 1944; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T. Chūgoku kenchiku teien to Hōōdō 中國建築庭園と鳳凰堂 [Chinese garden architecture and the Phoenix Hall]. In Byōdōin taikan 平等院大観 [Grand Scenes of the Byōdōin Temple]; Akiyama, T., Ed.; Iwanami Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 1988; Volume 1, p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, H. Heian jidai bukkyō kenchikushi no kenkyū: Jōdokyō kenchiku o chūshin ni 平安時代仏教建築史の研究: 浄土教建築を中心に [A Study of the History of Buddhist Architecture in the Heian Period: Focusing on Architecture of Pure Land Buddhism]; Chūōkōron Bijutsu Shuppan: Tokyo, Japan, 1992; pp. 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang Academy (Ed.) Dunhuang Shiku Quanji 1999–2005 敦煌石窟全集 1999–2005 [Comprehensive Collection of the Dunhuang Grottoes 1999–2005]; Shangwu Yinshu Guan: Hong Kong, China, 2005; 26 Volumes. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang Academy (Ed.) Dunhuang Shiku Yishu 1993–1998 敦煌石窟藝術 1993–1998 [Art of the Dunhuang Caves 1993–1998]; Jiangsu Meishu Chuban She: Nanjing, China, 1998; 22 Volumes. [Google Scholar]

- Digital Dunhuang Website. Available online: https://www.e-dunhuang.com/ (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- International Dunhuang Project Website. Available online: http://idp.bl.uk/ (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- “Dunhuang Mogao Caves” on the Digital Silk Road Project Website. Available online: http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/china-caves/dunhuang/ (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Sun, Y.; Zhou, Z. Mogao ku di 254, 257 ku zhongxinzhu ku de fuyuan yanjiu yu mingcheng kao: Tasi 莫高窟第254、257窟中心柱窟的復原研究與名稱考—塔寺 [A reconstruction study of the Mogao central-pillar Caves 254 and 257 and A study of the nomenclature “pagoda-temple”]. Zhongguo Jianzhu Shilun Huikan 中國建築史論彙刊 [J. Chin. Archit. Hist.] 2019, 18, 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Fan, J. Dunhuang Zhenshi Yu Xini 敦煌·真實與虛擬 [Dunhuang: Real and Virtual]; Zhejiang Daxue Chuban She: Hangzhou, China, 2003; pp. 99–270. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, W. Guanyu dunhuang mogaoku kuqian diantang yu kuyan jianzhu de shidai wenti 關於莫高窟窟前殿堂與窟簷建築的時代問題 [On the date of the hall in front of caves and cave eaves in Mogao grottoes]. Kaogu Yu Wenwu 2003, 1, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y. Mogaoku nanqu kuyan jianzhu yiji diaocha yanjiu 莫高窟南區窟簷建築遺跡調查研究 [A survey of the traces of façade architecture in the south section of the Mogao grottoes]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 2019, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z. From Earth to Heaven: An Architectural Spectacle of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves. Athanor 2022, 39, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. Between Virtual and Real: A New Architecture of the Dunhuang Mogao Caves. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Chicago, Chicago, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, W. Dunhuang Tulufan yijing sanzang fashi facheng gongde ku kao 敦煌吐蕃譯經三藏法師法成功德窟考 [A study of the merit cave of Facheng, the sūtra translator triple tripaka dharma master of Tibetan Dunhuang]. Zhongguo Zangxue 中國藏學 [China Tibetol.] 2008, 3, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X. Dunhuang tubo shiqi ta, ku chuizhi zuhe xingshi fenxi tanxi—Tubo tongzhi dunhuang shiqi de mijiao yanjiu zhi wu 莫高窟吐蕃時期塔, 窟垂直組合形式探析——吐蕃統治敦煌時期的密教研究之五 [A preliminary study of the vertical configuration of cave and pagoda during the Tibetan period at the Mogao caves—The fifth in the series studies of esoteric Buddhism at Dunhuang during the Tibetan-Occupied period]. Zhongguo Zangxu 中國藏學 [China Tibetol.] 2012, 3, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gansu Sheng Wenwu Ju 甘肅省文物局 [Bureau of Cultural Relics in Gansu Province]. Gansu Guta Yanjiu 甘肅古塔研究 [A Study of the Ancient Pagodas in Gansu Province]; Kexue Chuban She: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.-Z. Dunhuang Mogao Ku “Cishi Zhi Ta” Zhi Yanjiu 敦煌莫高窟“慈氏之塔”之研究 [A Study of the Earthen Pagodas at the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang]. Master’s Thesis, Yuan Kuang Institute of Buddhist Studies, Taoyuan, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J. Dunhuang Mogao Ku Tuta Yanjiu 敦煌莫高窟土塔研究 [A Study of the Earthen Pagodas at the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang]; Kexue Chuban She: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- International Dunhuang Project. Russian Explorations in Chinese Central Asia. Available online: http://idp.bl.uk/pages/collections_ru.a4d (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Kreitner, G. Im fernen Osten. Reisen des Grafen Bela Széchenyi in Indien, Japan, China, Tibet und Birma in den Jahren 1877–1880; Vero: Wien, Austria, 1881. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M.A. Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal Narrative of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China; Macmillan: London, UK, 1912; 2 Volumes. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkirk, P. Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia; Murray: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Menshikova, M.L. The Dunhuang Collection in the Hermitage. In Visualizing Dunhuang: The Lo Archive Photos of the Mogao and Yulin Caves; Ching, D.C.Y., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 9, pp. 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dudin, S.M. Monuments of Architecture in Western Turkestan. Arhitektruno-Hudozectchennyi Ezeniedielnik, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Dudin, S.M. Zhongguo Xinjiang de Jianzhu Yizhi 中國新疆的建築遺址 [Architectural Remnants in Xinjiang, China]; He, W.; Fang, J., Translators; Zhonghua Shuju: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.S. Repository of Ingenuity: Cave 61 and Artistic Appropriation in Tenth-Century Dunhuang. Art Bull. 2012, 94, 199–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Dunhuang jingbian hua fosi nei shuiti yu lutai bujv yanjiu 敦煌經變畫佛寺內水體與露臺佈局研究 [The water-platform layout of Buddhist temples in sūtra-illustration murals of the Dunhuang caves]. Jianzhu Shi 建築史 [Archit. Hist.] 2009, 2, 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. 6–11 shiji Mogao ku jingtu bian jianzhu tuxiang sheji yu pingmian buju yanjiu 6–11世紀莫高窟淨土變建築圖像設計與平面佈局研究 [A study of the visual design and layout of the architectural images in the pure land transformation tableaux in the Mogao caves of the sixth to eleventh century]. Zhongguo Jianzhu Shilun Huikan 中國建築史論彙刊 [J. Chin. Archit. Hist.] 2019, 18, 117–228. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L. 莫高窟148窟東方藥師經變中建築群佈局的推想 [Speculations on the architectural layout in the medicine buddha transformation tableau in Mogao Cave 148]. Jianzhu Yichan 建築遺產 [Herit. Archit.] 2022, 26, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Hantang Meishu Kongjian Biaoxian Yanjiu: Yi Dunhuang Bihua Wei Zhongxin 漢唐美術空間表現研究: 以敦煌壁畫為中心 [Representations of Space in Chinese art from the Han to the Tang Dynasty: A Study Based on Dunhuang Murals]; Zhongguo Renmin Daxue Chuban She: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Dunhuang Xifang Bian Kongjian Jiegou Yanjiu 敦煌西方變空間結構研究 [A Study of the Spatial Structure in the Western Pure Land Transformation Tableaux of Dunhuang]; Gugong Chuban She: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Steinhardt, N.S.; Harrer, A. Traditional Chinese Architecture: Twelve Essays; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 31–139, 226–252. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. Zhongguo Hanchuan Fojiao Jianzhu Shi: Fosi De Jianzao, Fenbu Yu Siyuan Gejv, Jianzhu Leixing Ji Qi Bianqian 中國漢傳佛教建築史: 佛寺的建造, 分佈與寺院格局, 建築類型及其變遷 [The History of Chinese Buddhist Architecture]; Qinghua Daxue Chuban She: Beijing, China, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 215–224, 288–306. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, N.S. Chinese Architecture in an Age of Turmoil, 200–600; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2014; pp. 95–248. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, C. Shina Sansei Unko no sekkutsu ji 支那山西雲岡の石窟寺, Part I [The cave temples of Yungang in Shanxi province, China]. Kokka 國華 1906, 197, 431–435. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, C. Shina Sansei Unko no sekkutsu ji 支那山西雲岡の石窟寺, Part II [The cave temples of Yungang in Shanxi province, China]. Kokka 國華 1906, 198, 483–494. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N. Dunhuang Mogao Ku Yu 6–11 Shiji Fosi Kongjian Bujv Yanjiu 敦煌莫高窟與6–11世紀佛寺空間佈局研究 [Research on Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang and Spatial Layout of Buddhist Monasteries from the Sixth to Eleventh Century]. Ph.D. Dissertation, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N.; Duan, Z. Dunhuang Mogao Ku Yu 6 Zhi 11 Shiji Fojiao Kongjian Buju Yanjiu 敦煌莫高窟與6至11世紀佛教空間佈局研究 [Research on Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang and Spatial Layout of Buddhist Monasteries from the Sixth Through Eleventh Century]; Zhongguo Jianzhu Gongye Chuban She: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. “Kongjian” de meishu shi “空間”的美術史 [Space in Art History]; Qian, W., Translator; Shanghai Renmin Chuban She: Shanghai, China, 2017; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Vinzent, J. From Space in Modern Art to a Spatial Art History: Reassessing Constructivism Through the Publication “Circle” (1937); De Gruyter Oldenbourg: München, Germany, 2019; pp. 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, S.K. Art and Practice in a Fifth-Century Chinese Buddhist Cave Temple. Ars Orient. 1990, 20, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, E.Y. Shaping the Lotus Sūtra: Buddhist Visual Culture in Medieval China; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kyan, W. Family Space: Buddhist Materiality and Ancestral Fashioning in Mogao Cave 231. Art Bull. 2010, 92, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-C. Relocating and Relocalizing Mount Wutai: Vision and Visuality in Mogao Cave 61. Artibus Asiae 2013, 73, 77–136. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, A.N. Water, Ice, Lapis Lazuli: The Metamorphosis of Pure Land Art in Tang China. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Chicago, Chicago, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chanchani, N. Mountain Temples & Temple Mountains: Architecture, Religion, and Nature in the Central Himalayas; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.Y. Architecture and Land on the Dark Side of the Moon: The Mogao Caves and Mount Sanwei. In Visualizing Dunhuang: The Lo Archive Photos of the Mogao and Yulin Caves; Ching, D.C.Y., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 9, pp. 149–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.S. Temples in the Cliffside: Buddhist Art in Sichuan; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Duara, P. The Crisis of Global Modernity: Asian Traditions and a Sustainable Future; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 281–282. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. Spatial Dunhuang: Experiencing the Mogao Caves; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. Kongjian de Dunhuang: Zhoujin Mogao ku 空間的敦煌: 走近莫高窟 [Spatial Dunhuang: Approaching the Mogao Caves]; Sanlian Chuban She: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. Shiku yanji meishu shi fangfalun ti’an—Yi Dunhuang Mogao ku wei li ‘石窟研究’美術史方法論提案—以敦煌莫高窟為例 [A proposal of an art historical methodology of “cave studies”—In the case of the Dunhuang Mogao caves]. Wenyi Yanjiu 文藝研究 [Lit. Art Stud.] 2020, 12, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, W.C. The Han-Tang Miracle at Dunhuang. In Art as History: Calligraphy and Painting as One; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Cave 45 Virtual Immersive Experience (2-D Version). YouTube Video. Available online: https://youtu.be/0uUIjgIH-5s (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Kenderdine, S. “Pure Land”: Inhabiting the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang. Curator Mus. J. 2013, 56, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AR MR XR. Huawei Cyberverse, AR Map App, Augmented Reality. YouTube Video 00:00–01:24. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YPbcNh_yN-o (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Jeffrey Shaw Compendium. Pure Land 360. Available online: https://www.jeffreyshawcompendium.com/portfolio/pure-land-360/ (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Jeffrey Shaw Compendium. Pure Land AR. Available online: https://www.jeffreyshawcompendium.com/portfolio/pure-land-ar/ (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Yang, H.; Wang, Q. Dunhuang Mogao ku shiku jianzhu xingzhi yu jiegou tezheng tanxi 敦煌莫高窟石窟建築形制與結構特徵探析 [Investigation of the architectural typology and structural features of the Dunhuang Mogao caves]. Xibei Daxue Xuebao (Ziran Kexue Ban) 西北大學學報 (自然科學版) 2022, 52, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhang, C.; Yao, J. Design of a virtual reality serious game for experiencing the colors of Dunhuang frescoes. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. Recarving the Dunhuang Grottoes: On the Roles of Architecture in the Process of Copying Buddhist Pure Land LANDSCAPES. Master’s Thesis, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Wu, J.; Yu, T.; Ding, X. Mogao ku di 172 ku beibi jianzhu tuxiang de sanwei shuzihua chengxian 莫高窟第172窟北壁建築圖像的三維數位化呈現 [3D digital rendering of architectural images in Mogao Cave 172]. Wenwu Baohu Yu Kaogu Kexue 文物保護與考古科學 [Sci. Conserv. Archaeol.] 2022, 34, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, J. “Shuzi bihua jianzhu” Dunhuang bihua zhong de jianzhu shuzihua jiangou: Yi Dunhuang Mogao ku di 361 ku nanbi xiqi diyi pu bihua tuxiang zhong fosi jianzhu weili “數字壁畫建築”敦煌壁畫中建築的數位化構建—以敦煌莫高窟第361窟南壁西起第一鋪壁畫圖像中佛寺建築為例 [Digital construction of the architecture in Dunhuang murals—With a case study of the Buddhist temple architecture in a painting in Mogao Cave 361]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 2022, 192, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- “Thousand Years of Construction” Website. Available online: https://www.youconf.cc/websites/dunhuang/index.html#video (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Zhang, Y. Dunhuang Bihua Zhong De Jianzhu ‘Huo’ Le 敦煌壁畫中的建築‘活’ 了 [Architecture Images in the Dunhuang Murals Have Been “Enlivened”]. Renmin Ribao (Haiwai Ban) 人民日報 (海外版) [China Daily (Overseas Version)], 7 June 2022. Available online: http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrbhwb/html/2022-06/07/content_25921682.htm (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Rawson, J. The Power of Images: The Model Universe of the First Emperor and Its Legacy. Hist. Res. 2002, 75, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Vignato, G.; Hiyama, S.; Kieffer-Pülz, P.; Taniguchi, Y. Traces of the Sarvāstivādins in the Buddhist Monasteries of Kucha; Dev Publishers & Distributors: New Delhi, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Summers, D. Real Spaces: World Art History and the Rise of Western Modernism; Phaidon: New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 431. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Z. Dunhuang Architectural Studies, 1926–2024. Heritage 2025, 8, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8030101

Zhou Z. Dunhuang Architectural Studies, 1926–2024. Heritage. 2025; 8(3):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8030101

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Zhenru. 2025. "Dunhuang Architectural Studies, 1926–2024" Heritage 8, no. 3: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8030101

APA StyleZhou, Z. (2025). Dunhuang Architectural Studies, 1926–2024. Heritage, 8(3), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8030101