Abstract

Disrupted sleep is common among nursing home patients and is associated with cognitive decline and reduced well-being. Sleep disruptions may in part be a result of insufficient daytime light exposure. This pilot study examined the effects of dynamic “circadian” lighting and individual light exposure on sleep, cognitive performance, and well-being in a sample of 14 senior home residents. The study was conducted as a within-subject study design over five weeks of circadian lighting and five weeks of conventional lighting, in a counterbalanced order. Participants wore wrist accelerometers to track rest–activity and light profiles and completed cognitive batteries (National Institute of Health (NIH) toolbox) and questionnaires (depression, fatigue, sleep quality, lighting appraisal) in each condition. We found no significant differences in outcome variables between the two lighting conditions. Individual differences in overall (indoors and outdoors) light exposure levels varied greatly between participants but did not differ between lighting conditions, except at night (22:00–6:00), with maximum light exposure being greater in the conventional lighting condition. Pooled data from both conditions showed that participants with higher overall morning light exposure (6:00–12:00) had less fragmented and more stable rest–activity rhythms with higher relative amplitude. Rest–activity rhythm fragmentation and long sleep duration both uniquely predicted lower cognitive performance.

1. Introduction

Typical reported indoor lighting levels in care homes may be insufficient for proper circadian entrainment [1,2,3,4]. Light is the dominant time cue (zeitgeber) for entraining the circadian clock to local time [5,6]. A central pacemaker in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) generates 24 h rhythms in physiology and behavior, including sleep and activity. The SCN receives light information from intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells that contain the photopigment melanopsin [7,8,9]. In humans, the action-spectrum for non-visual light responses peaks in the blue range, between 420–480 nm [10,11,12,13,14,15].

Older adults are particularly susceptible to circadian rhythm disturbance. Aging is associated with cellular changes in the SCN, particularly in patients with dementia [16]. Additionally, age-related eye problems and retinopathies—such as senile miosis, cataracts, and optic nerve degeneration—impair ocular light transmission to the SCN [17,18,19], especially for short-wavelength blue light [20,21]. Age-related circadian rhythm disturbances include advanced circadian phase (early sleep timing), a dampening in the amplitude of circadian rhythms and more fragmented and less stable rest–activity rhythms [16,22,23,24,25,26]. Between 40 and 70% of older adults suffer from sleep disturbances, with an increased frequency in older adults with dementia [27].

Circadian rhythm disturbances and poor sleep have been linked to cognitive decline and poor health in older adults [28]. Compared to age-matched healthy adults, patients with dementia have a more fragmented and lower amplitude 24 h rest–activity rhythm [29,30,31]. Reduced amplitude, instability and fragmentation of the 24 h activity rhythm are also linked to depression in older adults [32], even when symptoms are mild, which is common in elderly persons.

Increasing zeitgeber strength may help compensate for the age-related reduced responsiveness to light. Residents of senior homes show positive effects of higher photopic illuminance on rest–activity rhythms [33,34,35,36,37,38], mood and anxiety [35,39,40]. Long-term exposure to high illuminance (e.g., 1000 photopic lux for 15–42 months) during the day has been shown to slow down cognitive deterioration in senior home residents with Alzheimer’s disease [39]. Increased light exposure has also been shown to improve sleep and cognitive performance in community-living elderly people without dementia [41]. An alternative to bright light exposure is blue-enriched lighting designed to deliver high circadian stimulation during the day. Figueiro and colleagues [35,42] found improved sleep and mood and reduced agitation following four weeks of blue enriched light (9325 K/~324 lux and 5000 K/~600 lux at the eyes) exposure in institutionalized patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Hopkins and colleagues [40] found positive (increased daytime activity and reduced anxiety) and negative (increased night-time activity, reduced sleep efficiency and quality, advanced rest–activity rhythm) effects of daytime blue-enriched lighting (17,000 K/~900 lux at 1.6 m in the direction of gaze) in senior home residents without dementia. Other lighting intervention studies in senior homes found no effects of photopic illuminance and dynamic lighting [43,44,45].

The efficacy of light is dependent on the biological time-of-day (circadian phase) of light exposure. Daytime light exposure, especially in the morning, is associated with improved sleep, mood, alertness, and cognition [36,37,39,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54], whereas light exposure in the evening and night-time has been shown to have acute disruptive effects on sleep by delaying circadian timing (e.g., later sleep timing) and suppressing the release of melatonin [55,56,57]. It is thus essential to schedule light exposure in accordance with the circadian variation in the response to light. New developments in light-emitting-diode (LED) technology now enable light to be programmed (dynamic) to provide high intensity blue-enriched light during the day and low intensity, warm light at night. At present, research on dynamic lighting to promote circadian entrainment is limited. Muench and colleagues [43] found no effect of dynamic lighting on the rest–activity and melatonin profiles, emotions, and agitation behaviour in patients with severe dementia. However, they did observe a significant effect of individual light exposure, whereby residents with higher average daily light exposure showed longer emotional expression of pleasure and alertness, higher quality of life, less time spent in bed, and later bed and sleep times. Higher individual daytime light levels in senior home residents have also been shown to predict fewer night-time awakenings and a later acrophase (peak) of the daily rest–activity cycle [46].

The current pilot study examines the effect of dynamic lighting—changing in intensity (~80–1000 photopic lux) and colour temperature (~2700–5000 K) over the 24 h day to mimic the natural light/dark cycle of the sun—on sleep, cognition, and well-being (depression, fatigue, and sleep-quality) in 14 senior home residents. Participants wore wrist accelerometers to track 24 h sleep, rest–activity, and light exposure profiles over a 75 day period consisting of 5 weeks of conventional lighting (control condition, ~320 photopic lux and ~3500 K) and 5 weeks of circadian lighting (experimental condition), in a counterbalanced order. At the beginning of the study, prior to the manipulations of lighting, baseline cognitive performance was assessed. At the end of each condition, cognitive performance (week 4 of each condition) and self-reported depression, fatigue, and sleep quality (week 5 of each condition) were assessed. As the effect of lighting can take several weeks to impact physiology and behaviour, the last valid 14 days of each condition were used for statistical analyses (see Materials and Methods).

We predicted that circadian lighting, compared to conventional lighting, would (1) enhance circadian rhythm amplitude and stability of entrainment, as indicated by increased sleep duration, better sleep quality (less frequent awakenings and higher sleep efficiency), reduced rest–activity fragmentation (lower intradaily variability), stabilization of the rest–activity rhythm (higher interdaily stability), and higher relative amplitude of the rest–activity rhythm; (2) improve performance on cognitive batteries (Pattern Comparison and Processing Speed Test; Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test; Dimensional Change Card Sort Test); and (3) improve well-being (lower depression and fatigue and better sleep quality). Given that brighter morning light conditions have been associated with improved sleep, mood, and cognition, we also predicted that participants with higher levels of morning light exposure would exhibit stronger rest–activity rhythms and better cognitive performance and well-being (lower depression and fatigue and improved sleep quality).

2. Results

2.1. Participant Demographics

We studied 14 (two male) senior home residents between the age of 70–94 years (M = 82.6 ± SD = 6.6). Participants were randomly assignment to either group A (5 weeks experimental followed by 5 weeks control) or B (5 weeks control followed by 5 weeks experimental; see Supplementary Table S1 for group demographics). The ethnic background of participants was primarily Asian (N = 11). Seven participants resided in assisted-living suites and seven in independent-living suites. The majority of participants were early chronotypes (see Supplementary Table S2) relative to the general adult population [58]. Participants’ chronotype, assessed using the ultra-short version of the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire (µMCTQ), ranged from extremely early (mid-sleep = 0.6 h past midnight) to intermediate (mid-sleep = 4.08 h past midnight). Our sample included participants with impaired cognitive performance. Averaged uncorrected standardized scores in the Pattern Comparison and Processing Speed Test were relatively low (73.07 ± 18.25, range from 47 to 103) with five participants scoring below two standard deviations from the National Institute of Health (NIH) toolbox population mean (100 ± 15).

2.2. Condition Effects

2.2.1. Actigraphy

Actigraphy data were collected over a period of 75 days from each participant. Activity counts for each minute of the day were imported to Actiware software to generate 24 h actigraphy plots. Intervals with watch removals exceeding 5% invalid time SW or invalid time L (see Table 5 for definitions of study variables) were excluded, except for 24 h sleep duration where a 10% threshold was used (see Section 4). An interval refers to a time interval, which can either be manually entered into Actiware (e.g., 6:00 to 12:00) or computed by Actiware (e.g., sleep interval) based on a participants’ activity profile. After exclusions, total valid days of data collection averaged 58.4 ± 16.6 complete nights (range 24–75 nights) and 53.2 ± 16.2 complete days (range 20–72 days).

Values for daily total and maximum white light exposure were obtained by Actiware software and averaged for each participant over the last 14 days (minimum of 10 days and nights, excluding incomplete/missing days/nights) of data collection in each condition (see Section 4). Related samples Wilcoxon signed rank tests showed that the two conditions did not differ in total or maximum white light exposure in the morning (6:00–12:00) or evening (20:00–0:00) hours (see Table 1 for sample means (M) and standard deviations (SD) and medians). During the nighttime hours (22:00–6:00), there was a significant difference (of 31 photopic lux) in maximum white light exposure between conditions, with higher white light intensities in the control condition.

Table 1.

Light exposure per condition and Wilcoxon signed rank test comparisons.

Values for daily sleep variables (nocturnal sleep duration, sleep latency, wake after sleep onset (WASO), sleep efficiency) as well as 24 h sleep duration (sum of daily rest interval sleep minutes) were obtained by Actiware and averaged for each participant over the last 14 days (minimum of 10 days and nights, excluding incomplete/missing days/nights) of data per condition (see Section 4). Minute-bin activity counts were imported to Clocklab software to compute daily activity onset (AO), acrophase, as well as relative amplitude (RA), intradaily variability (IV) and interdaily stability (IS) in each condition. Incomplete days were excluded. In the case of interrupted data collection (e.g., missing days), we used the sequence with the most days (minimum of 5 consecutive days) over the last 14 days of data per condition. Definitions of dependent variables are provided in Table 5 in Section 4.

Table 2 contains sample median values of the sleep and rest–activity variables in the experimental and control conditions and Wilcoxon signed rank test z scores. Wilcoxon signed rank tests revealed no significant difference in sleep and rest–activity variables between conditions. Mixed design ANOVA comparing sleep and rest–activity variables between conditions (within-subject comparisons) with group (A vs. B based on order of condition) as a between-subject factor showed no significant effects of condition, group, or condition*group, except for acrophase, where there was a significant between-subject effect of group (F(1, 12) = 7.219, p = 0.02) and a significant interaction (F(1, 12) = 9.423, p = 0.01). Both groups delayed in acrophase by an average of 30.5 ± 36.5 min over weeks of data collection (from end August to mid-October), with group A delaying in mean acrophase from 14.01 to 14.64 (38 ± 36 min) and group B from 12.27 to 12.65 (23 ± 38 min). Levene’s test indicated homogeneous variances for both conditions.

Table 2.

Sample median values of study variables per condition and Wilcoxon signed rank tests.

2.2.2. Cognition

NIH toolbox raw scores on the Pattern Comparison and Processing Speed Test and computed scores on the Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test and Dimensional Change Card Sort Test were used. Two participants (one from group A and one from group B) were absent for the second assessment of cognitive batteries (travel and illness) and three participants (two from group A and one from group B) only completed the Pattern Comparison Processing Speed Test due to task difficulty. One of these three participants (group A) was able to complete the Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test for the first (experimental condition) but not the second testing (control condition). This self-selection bias resulted in overall higher scores in the Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test and Dimensional Change Card Sort Test.

Related samples Wilcoxon signed rank tests showed no significant difference between conditions for the three cognitive batteries (see Table 2). Mixed design ANOVA comparing scores between conditions (within subject comparison) and groups (between-subject factor) showed no effects of condition, group or group*condition for the Pattern Comparison and Processing Speed Test and Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test. There was a significant between-subjects effect of group (F(1, 7) = 11.39, p = 0.012; group A had higher scores) and a trend (p < 0.1) for a significant group*condition interaction on the Dimensional Change Card Sort Test (F(1, 7) = 4.518, p = 0.071). Wilcoxon signed rank test revealed a significant improvement in computed scores in the Dimensional Change Card Sort Test from test session one to test session two: z = −2.13, p = 0.033, likely due to a learning effect. Additionally, we found no effect of condition on the three cognitive tests when controlling for baseline performance as a covariate in repeated design ANOVA.

2.2.3. Well-Being

For each participant, we computed scores of depression (Geriatric Depression Scale), fatigue (Daily Fatigue Form), and sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, sleep quality item) in the control and experimental conditions. One participant was absent for the second assessment of questionnaires (illness) and one participant did not answer the sleep quality item. In the control condition, three participants reported mild depression, one moderate depression and one severe depression. It is worth noting that the two participants who reported moderate and severe depression reported only mild depression in the experimental condition. Table 2 shows sample median scores from the questionnaires in the control and experimental conditions and Wilcoxon signed rank test z scores. There was no significant difference in participants’ scores of depression and sleep quality. There was a trend for lower fatigue in the experimental condition, which went away after Bonferroni correction for multiple tests.

2.2.4. Lighting Feedback

Table 2 shows participants’ subjective assessment of the lighting in both conditions on a 6-point scale ranging from −3 (extremely dissatisfied) to 3 (extremely satisfied). Two participants were absent for the second assessment (illness and travel). There was no significant difference in participants’ liking of the experimental versus control lighting.

2.3. Pooled Data: Individual Light Exposure

We computed participant averages for all sleep and activity variables over the span of their study participation (58.4 ± 16.6 nights and 53.2 ± 16.2 days). In the case of interrupted data collection (e.g., missing days), we computed separate values for each sequence of consecutive days (minimum 5 days) and averaged across sequences. We pooled uncorrected standardized scores from the three cognitive batteries and scores from the questionnaires over both conditions. See Supplementary Table S3 for sample means and standard deviations of study variables.

Participants slept an average of 6.75 ± 1.21 h a night, which is comparable to the observed sleep duration of 6.38 ± 0.95 in 1734 older adults reported by Luik and colleagues [32] (t(13) = 1.15, p = 0.270). Participants napped on average 39 ± 82 min a day (range 0–254 min). With naps included, participants slept an average of 7.41 ± 1.83 h a day. Additionally, mean sleep latency (21.42 ± 11.11, t(13) = 1.24, p = 0.235) and WASO (80.52 ± 29.24, t(13) = 1.42, p = 0.180) were comparable to the values reported by Luik and colleagues [32]. On average, participants in our sample woke up for 80.5 min a night, with a range of 47–149 min. However, compared to Luik’s sample of older adults [32], our sample had a significantly higher IV (t(13) = 9.387, p ≤ 0.000) and lower IS (t(13)= −7.80, p ≤ 0.000), indicating a more fragmented and less stable rest–activity cycle.

Table 3 shows the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients between participants’ total white light exposure in the morning (6:00–12:00), evening (20:00–00:00) and night (22:00–6:00) and participants’ sleep and rest–activity, processing speed (uncorrected standardized scores) and questionnaire scores (depression, fatigue, and sleep quality) pooled over both conditions. Participants with greater morning light exposure had significantly lower IV and higher IS and RA. Morning light correlations with IV, IS and RA remained significant (p ≤ 0.05) after controlling for activity onset with two-tailed partial correlations (r = −0.722 p = 0.005; r = 0.587 p = 0.035; r = 0.656 p = 0.015). Participants with greater morning light exposure also tended (p < 0.1) to have higher scores on the processing speed test. High evening light exposure correlated with shorter sleep duration and a trend (p < 0.1) towards later acrophase and reduced fatigue.

Table 3.

Correlations between white light exposure and main outcome variables.

Table 4 contains Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients between all outcome variables. Participants with low processing speed (PS) had significantly higher IV and longer nocturnal sleep duration. Participants with processing speed scores below 70 (over 2 SD below the population mean) slept on average two hours (124 min) longer per night compared to residents with higher processing speeds (scores above 70).

Table 4.

Correlations between main study variables.

To further explore the relationship between morning light exposure, rest–activity rhythm, and processing speed, we ran a series of forced entry multiple regressions in SPSS to predict IV, IS, RA and processing speed (see Supplementary Tables S4–S7), entering morning light (6:00–12:00) and potential confounding variables as predictors. Results show that morning light exposure predicted participants’ IV, IS and RA, after controlling for age, chronotype, depression, fatigue, and processing speed. Morning light exposure did not predict processing speed after controlling for age, IV and nocturnal sleep duration. Both IV and sleep duration uniquely predicted processing speed, independent of age and morning light exposure.

3. Discussion

This study examined the effects of dynamic circadian lighting—changing in intensity and colour temperature over the 24 h day—on sleep, cognitive performance, and well-being in 14 senior home residents between the age of 70–94 years. The study was conducted as a within-subject study design over 5 weeks of circadian lighting and 5 weeks of conventional lighting, in a counterbalanced order. Participants wore wrist accelerometers to track rest–activity and light exposure and completed cognitive batteries (NIH toolbox) and questionnaires (depression, fatigue, sleep quality, lighting appraisal) at the end of each condition. We found no effect of lighting condition on residents’ sleep duration, sleep latency, sleep efficiency, nocturnal awakening, and rest–activity phase, fragmentation, stability, and amplitude. Additionally, there was no effect of lighting condition on participants’ cognitive performance and well-being, and participants’ rating of both lighting conditions showed no preference for circadian over conventional lighting. Individual light exposure levels varied greatly between participants but did not differ between lighting conditions, except at night (22:00–6:00), where conventional lighting had a higher maximum light output than circadian lighting.

Our results confirm that circadian rhythms in senior home residents are highly disturbed, with greater disturbance in cognitively impaired residents [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Consistent with previous research [22,23,24,25,26], our sample had phase advanced and low amplitude rest–activity rhythms that were highly fragmented (high IV) and variable over time (low IS). We found IV to be a significant predictor of impaired cognitive performance, which is also consistent with previous research [4,29,30,31]. Fragmented activity rhythms have been observed in patients with early-onset dementia [59] and have been hypothesized to contribute to neurodegenerative processes [23,60,61,62]. Consistent with previous research [4,46], long sleep duration, independent of IV, was also a significant predictor of impaired cognitive performance, whereby participants with lower processing speed spent more time sleeping, especially at night. Circadian rhythm disturbances have been shown to be most pronounced in adults over the age of 80 years [25,63]. The majority of our sample (11/14) exceeded 80 years in age.

Pooled data from both conditions showed that participants with higher morning light exposure (6:00–12:00) had less disrupted rest–activity rhythms (less fragmented and more stable rhythms, and higher relative amplitude) even when controlling for potential confounding variables such as activity onset, age, chronotype, depression, fatigue, and cognitive performance. Although the direction of causality in this association is not known, one possible interpretation is that morning light exposure strengthens circadian entrainment and buffers cognitive decline in senior home residents. This is a cause for concern, given that older adults generally receive little daytime light exposure [1,2,3,4], particularly so for institutionalized older adults with dementia, who have been reported to experience as little as 2 min a day of bright light [3,64]. Current COVID-19 pandemic restrictions are likely to further limit older adults’ exposure to outdoor light. Of particular concern are winter months, when reported light exposure levels are even lower compared to summer months [65,66]. Decreased light exposure during winter months is also associated with a delay in circadian phase [67,68]. Consistent with this, our sample showed a significant delay in acrophase from August to October.

Our study has several limitations: First, although the number of days of data collection for each participant was high, the total participant sample size was low, which reduces the probability of detecting a treatment effect.

Second, light intensities in the treatment condition (~1000 photopic lux, horizontal plane) may have been too low to benefit circadian processes relative to the control condition. Light intensities >5000 photopic lux at the eye are recommended to treat depression, and other published lighting intervention studies have used 1000–2500 photopic lux at the eye level, in the direction of gaze, e.g., [36,39]. Zeitzer and colleagues [57] found that half of the maximal phase delaying response achieved in response to a single episode of evening bright light (~9000 photopic lux in the horizontal angle of gaze) can be obtained with just over 1% of this light (dim room light of ~100 photopic lux in the horizontal angle of gaze) with a saturating response above ∼550 photopic lux in the horizontal angle of gaze. Figueiro recommends a minimum of 400–600 photopic lux at the cornea and a correlated colour temperature (CCT) > 5000 K during the day and a maximum of 80–100 photopic lux and a CCT < 2800 K at the cornea in the evening to promote circadian entrainment [69]. It is also worth noting that the lighting levels in our control condition were ~320 photopic lux ((~30 foot-candle (fc), horizontal plane)) at 5′ below the fluorescent fixture(s) in the apartments, which is higher than typically reported lighting levels in senior homes [1]. The lighting levels in our treatment condition may provide significant benefits in cases where the control lighting levels are lower than in our study.

Another potential study limitation is that the light intervention may have been too short to elicit detectable changes in behaviour. Longitudinal studies (e.g., 1–2 years, controlled for confounding effects of aging) may give more substantive results. Nonetheless, similar studies were able to find beneficial effects of lighting within 4 weeks, e.g., [35]. Additionally, our study took place during the late summer and early autumn (August to October 2019), when people generally receive high levels of daytime light exposure, compared to winter months. Seasonal differences in light exposure have also been shown in senior home residents and affect people with dementia disproportionately [65,66]. During winter months, older adults with dementia have lower light and activity levels and greater circadian rhythm disturbance compared to age-matched healthy adults [66]. Therefore, we expect a stronger effect of artificial lighting during winter months.

A final study limitation is that our accelerometer obtained light measurements that likely underestimated true illuminance values. The Actiwatch has poor illuminance-sensing accuracy under moderately intense artificial and natural sunlight conditions. Joyce and colleagues [70] found that the Actiwatch 2 increasingly underestimated true illuminance with increasing illumination, with the highest variability between photometer and Actiwatch illuminance for illuminance values over 2500 photopic lux. In response to ~20,000 photopic lux white LED light and 30,000 photopic lux sunlight, the Actiwatch 2 underestimated illuminance by recording only 25% and 46% of the true illuminance value, respectively. While calibrated research-grade photometers provide much more accurate quantifications of light levels, they are not practical for measuring the exposure of a freely moving individual over time. Additionally, relative to a location at the plane of the cornea, photosensors worn on the wrist underestimate the actual light levels received by the eye and the circadian system [71]. Jardim and colleagues found that compared to the eye level, the measurement differences were on average 50 photopic lux higher during the day and 50 photopic lux lower at night [72]. Additionally, our wrist-worn light sensors may at times have been obstructed by clothes and/or blankets. Although we advised participants to not cover their light sensors, we did not impose any clothing restrictions.

Comparisons between our study and previous lighting intervention studies are made difficult due to different methods, including light intensity, light source, duration and timing of light exposure, and the location of the lighting (e.g., communal rooms with varying participant accessibility). Spitschan and colleagues [73] recently proposed detailed minimum guidelines on reporting light exposure in human chronobiology and sleep research. Some standardization of lighting protocols and procedures would also benefit future studies of smart circadian lighting to improve sleep, cognition, and mood in the elderly.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Site and Participants

The study took place at two adjacent buildings at a residence for seniors. The residence provides 51 one-bedroom units and 8 studios for assisted-living residents (building I) and 32 one-bedroom units for independent living (building II) residents. The majority of residents are of Japanese-Canadian descent (first and second generation) with an age range of 65–100 years. The culturally sensitive residence offers social, recreational, and spiritual activities (e.g., chair gymnastics, music, crafts, tea and chat, church service). While all residents have a large degree of independence in day-to-day living, qualified staff are available as needed for personal assistance 24 h a day. Residents supply their own furniture and are encouraged to make their suites their own home. Each apartment has a full kitchen, a living room, one bedroom, one bathroom, a balcony, and a storage space. The executive director of the residence estimated the rate of dementia to be about 15–20%.

Initially, 19 (5 male) senior residents between the age of 70–105 volunteered to participate in this study. The inclusion criteria for participants were: (1) must currently live at the study site; (2) no intention to travel during the study period; (3) able to read and write in English or Japanese to a sufficient level in order to understand the consent form and complete questionnaires; (4) competent to consent. Two participants died and three participants withdrew from the study. Their data were not included in the data analyses. The final 14 participants (2 male) were between 70–94 years (82.6 ± 6.6). The ethnic background of the participants was primarily Asian (N = 11). Seven participants were assisted-living (building I) and seven were independent-living residents (building II). All 14 participants lived on their own, in one-bedroom suites. Harmonized ethics committee approval by Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia, and Fraser Health Authority was received prior to beginning the study (REB H18-02309).

4.2. Study Design

The study was conducted as a within-subject study design over 75 days during summer/fall (August to October) 2019. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups (group A and B) to counterbalance the order of conditions. Group A received 5 weeks of circadian lighting (experimental) followed by 5 weeks of conventional lighting (control). Group B received 5 weeks of conventional lighting (control) followed by 5 weeks of circadian lighting (experimental). At the beginning of the study, demographic information and the µMCTQ were assessed in a one-on-one interview. Participants’ sleep was continuously tracked with wrist accelerometers over a span of 75 days (35 days per condition, plus a few days prior to and in-between lighting manipulations). Analyses regarding experimental effects of lighting only include actigraphy data collected during the last 14 days of each condition. Participants’ cognitive performance (three batteries from the NIH toolbox) and well-being (scales of depression, fatigue, and sleep quality) were assessed during the last week of each condition during one-on-one appointments (30–60 min) in the participants’ homes or common rooms. A baseline cognitive performance was assessed at the beginning of the study, prior to experimental light manipulation. One-on-one interviews and assistance were provided in either English or Japanese, depending on the language fluency of the participant. The study was not blinded. Participants had to approve of lighting installations inside their private living space and participants and researchers were able to recognize treatment conditions due to visible differences in emitted light in both conditions.

Lighting Conditions

During the 5 week experimental condition, Nano-Lit Quantum dot LED lighting (Nano-Lit Technologies, Vancouver BC, Canada) was installed in the residents’ private suite kitchen/living room area and bathroom. During the 5 week control condition, participants were exposed to their conventional lighting in the kitchen/living room area. The lighting could be switched on or off manually, but participants were asked not to use the light switch during the experimental condition (a reminder note was taped next to the light switch). To ensure uniformity between suites, new 2700 Kelvin (K) LED light bulbs were installed in all the suites’ bedroom, hallway, and dining areas (A19 60 W lamps, Philips 9.5A19/LED/827/E26/DIM 1PK 8/1) for both conditions. Additionally, a 2700 K safety smart sensor night light (Emotionlite Plugin Night Light 2700 K) was installed in the bathrooms to discourage participants from switching on the bathroom lights at night. The two buildings differed in ceiling height and number of retrofit light fixtures. Building I had a 9’ ceiling height and retrofitted 2 lighting fixtures. Building II had a ceiling height of 8′ and retrofitted a single light fixture.

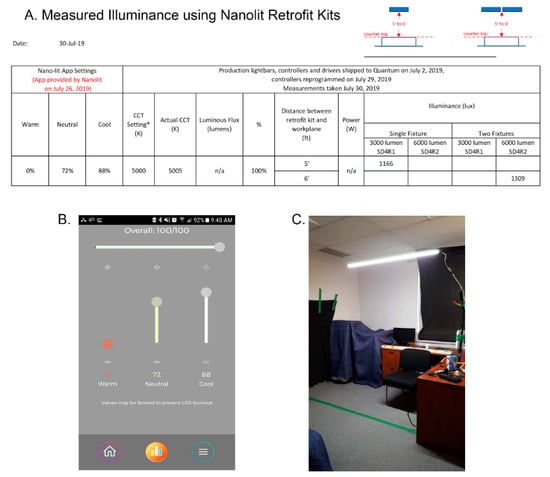

Experimental condition: in contrast to typical LED light, which uses a yellow phosphor-based coating to create white light, Quantum Dot LED lighting uses nanocrystals that can be tuned to emit all colors across the visible spectrum. This creates high-quality white light with precise color temperatures and high colour rendering. The colour rendering index (CRI) was 92 at 2700 K and at 4000 K and 97 at 6500 K. Photometric shop measurements on 30th July 2019 of the single fixture SD4R1 (3000 lumen) and double fixture SD4R2 (6000 lumen) at 100% intensity at 5000 K were completed at 6′ (building I) and 5′ (building II) from source (distance between the retrofit plane and countertop, see Figure 1). Measurements were taken remotely from the window so that daylight did not contribute to illuminance readings. Figure 1 shows the photometric shop light output measurements for double fixtures (6000 lumen) at 6′ and single fixtures (3000 lumen) at 5′. With 20% loss from existing light fixture lens, the light intensity was estimated to be 1047 photopic lux for building I and 933 photopic lux for building II. In situ measurements in one of the suites from building I, with two luminaires at 6′ distance between fixture and light meter, with the 6000 lumen Nano-Lit modules operating at 5000 K, recorded an illuminance of 915–970 photopic lux (85–90 fc). Photometric shop and in situ measurements were obtained at horizontal plane with an illuminance meter (model # 401025) by Extech Instruments.

Figure 1.

(A) Photometric shop light output measurements measured horizontally at 5′ and 6′ distance between retrofit plane and countertop (3′). * predicted CCT. (B) Screenshot of Nano-Lit app settings. (C) Photometric shop measurements were obtained remotely from the window so that daylight did not contribute to illuminance.

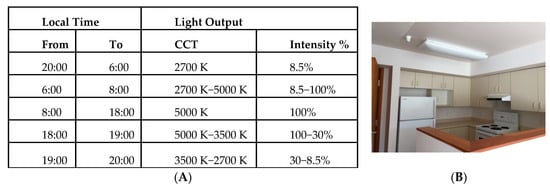

The circadian lighting was programmed on a 24 h cycle with gradual changes in light intensity and colour temperature over the 24 h day (see Figure 2). Manufacturer obtained tabulated spectra at 10 nm spacing between 380–730 nm are reported in Table S8 in the Supplementary Materials. As recently recommended (73), the spectral irradiance was converted into absolute α-opic radiances expressed in mW/(m2 sr) by weighting the spectrum by the spectral sensitivity of each of the five photoreceptors separately (L, M and S cones, rods, and melanopsin-encoded intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs)) and summing up the values across wavelength bands. This was obtained with CIE S 026 Toolbox v1.49a (https://doi.org/10.25039/S026.2018.TB) using the recently standardized spectral sensitivities CIE S 026/E:2018 [74]: CIE 10_cone fundamental, the CIE rod fundamental, and a standardized melanopsin spectral sensitivity. Our toolbox outputs for the 5000 K setting (8:00–18:00) are presented in the Supplementary Materials. Note, the toolbox input spectra at 5 nm spacing were extrapolated from the 10 nm spectra spacing provided to us by the manufacturer.

Figure 2.

(A) 24 h setting (building I) of correlated colour temperature (CCT) in Kelvin (K) and % light output intensity in the experimental condition and (B) photograph of study site and lighting fixture.

Control condition: during the 5 week control condition, participants were exposed to their conventional lighting in the kitchen/living room area. In situ measurements below the fluorescent fixture(s) in the apartments for both buildings measured an average of ~30 fc (320 photopic lux). Measurements were taken at night so that daylight did not contribute to illuminance readings. Measurements were made at horizontal plane with an illuminance meter (model #401025) by Extech Instruments.

4.3. Materials and Procedures

4.3.1. Wrist Accelerometers

Daily sleep and photopic light exposure profiles were assessed with 11 Actiwatch 2 (6 in group A and 5 in group B) and 3 Spectrum devices (1 in group A and 2 in group B) by Philips Respironics, Murrysville, PA. The wrist-worn devices use accelerometers to measure movement at 32 hz, which was binned into 1 min epochs, and use a light sensor to record illumination exposures ranging from 0.01 to more than 100,000 photopic lux. Actiwatch sleep–wake algorithms have been validated with polysomnography [75,76,77,78]. The accelerometers had to be removed from the wrist while bathing and were collected by research assistants for battery charging about every 7–14 days for up to 72 h at a time.

Activity counts for each minute of the day were imported to the Philips Respironics Actiware version 6.0.9 to generate 24 h actigraphy plots to visually inspect the participants’ sleep–wake cycle and obtain daily values for sleep and light variables (see Table 5). Intervals with more than two continuous hours of missing data were excluded to prevent a time-of-day effect. We manually excluded activity data when (a) the participant was known or had reported to have removed the watch, or (b) no activity counts were registered for >2 h. Often, nocturnal sleep was interrupted by extended periods of waking. In these cases, the software chose sleep onset and wake times from the longer of two sleep bouts during the nocturnal period. If the following criteria were met, then the two sleep bouts were joined to allow reported sleep onset and wake time to represent one sleep period across the entire nocturnal period (by using the sleep onset from the earlier bout and wake time from the later bout). Criteria for combining sleep periods were (a) the period of nocturnal activity occurred during µMCTQ reported sleep times; (b) the period of nocturnal activity occurred after the lights had been switched off, determined by visual inspection of light behavior (off/on); (c) the period of nocturnal activity occurred during a time when the subject was “usually” asleep/inactive as compared to their overall actigraphy data; (d) the participant must have been asleep for at least 2 h prior to the period of awakening; (e) the duration of the nocturnal awakening had to be shorter than the shortest period of sleep.

Table 5.

Definitions of sleep, light, and rest–activity variables.

Activity counts for each minute of the day were also imported to Clocklab version 6.1.0.1. (Actimetrics, Wilmette, IL, USA) 6 to quantify rest–activity variables using nonparametric indicators [79] by means of activity onset (AO), acrophase, intradaily variability (IV), interdaily stability (IS), and relative amplitude of the rhythm (RA). See Table 5 for variable definitions.

4.3.2. Cognitive Tests

Cognitive performance was assessed with three cognitive batteries from the National Institutes of Health Toolbox Cognition Battery (NIHTB-CB) [80] presented in an app on a touch screen tablet (iPad, 6th generation) in protected cases (Avawo kids case) that can be folded back into a stand for horizontal viewing or touching position. The battery was designed to provide a set of standardized tests that could be utilized across diverse study designs and populations in large cohort studies and clinical trials from ages 3–85. The NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery (NIHTB-CB) includes subtests that evaluate processing speed, executive function, and working memory. Uncorrected standard scores compare the performance of the test takers to those in the entire NIH toolbox nationally representative normative sample (100 ± 15), regardless of age or any other variable. Although the NIHTB-CB was not designed to substitute comprehensive neuropsychological assessment, data indicate it is a valid tool for broad assessment of cognition in dementia and predementia conditions [81].

Before the study began, all participants were extensively trained on the use of touch screens and the use of cognitive batteries so as to minimize learning effects. Participants were trained and tested on the cognitive batteries during one-on-one assessments with the same research personnel in the participants’ homes or common rooms. Communication during training and testing was either in English or Japanese, depending on the language fluency of the participant. Instructions (in English) appeared visually on the monitor (and at times auditorily) and were also read aloud (and if necessary, translated) by the research personnel. All practice and test sessions started with the NIH toolbox touchscreen tutorial and each test started with a practice block during which the participants were given feedback on whether a response was correct or not. During test administration, no feedback was provided by the research personnel. Test sessions took place on Saturday and Sunday mornings, either between 10:00–11:00 or 11:00–12:00. The day and time of participants’ test sessions were kept consistent over the study. We used the following three tests from the NIHTB-CB, in the order presented below:

- The Pattern Comparison and Processing Speed Test is a 3 min processing speed test. This test measures the speed of processing by asking participants to discern whether two side-by-side pictures are the same or not. The items are presented one pair at a time on the computer screen, and the participant is given 90 s to respond to as many items as possible (up to a maximum of 130 items). The participant’s raw score is the number of items answered correctly in a 90 s period, with a range of 0–130. Higher scores indicate a faster speed of processing. To evaluate simple improvement or decline over time, one can use the raw score obtained from each assessment. Slow processing speed has been associated with normal aging, with decreased processing speed being a significant contributor to age-related decline in other cognitive domains [82].

- The Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test is a 3 min test to assess a participant’s attention and inhibitory control. Participants are required to indicate the left–right orientation of a centrally presented arrow while inhibiting attention to the potentially incongruent stimuli that surround it. In some trials, the orientation of the flanking stimuli is congruent with the orientation of the central stimulus, and in others, it is incongruent. Performance on the incongruent trials provides a measure of inhibitory control in the context of visual selective attention. Scoring is based on a combination of accuracy and reaction time. The score provides a way of gauging raw improvement or decline from time 1 to time 2 (or subsequent assessments). This computed score ranges from 0–10, but if the score is between 0 and 5, it indicates that the participant did not score high enough in accuracy (80 percent correct or less). A change in the participant’s score from time 1 to time 2 represents real change in the level of performance for that individual since the previous assessment.

- The Dimensional Change Card Sort Test is a 4 min test designed to assess cognitive flexibility/task switching. Two target pictures are presented that vary along two dimensions (e.g., shape and color). Participants are asked to match a series of bivalent test pictures (e.g., yellow balls and blue trucks) to the target pictures, first according to one dimension (e.g., color) and then, after a number of trials, according to the other dimension (e.g., shape). “Switch” trials are also employed, in which the participant must change the dimension being matched. It consists of four blocks (practice, pre-switch, post-switch, and mixed). Scoring is based on a combination of accuracy and reaction time. The computed score provides a way of gauging raw improvement or decline from time 1 to time 2. This computed score ranges from 0–10, but if the score is between 0 and 5, it indicates that the participant did not score high enough in accuracy (80 percent correct or less). A change in the participant’s score from time 1 to time 2 represents real change in the level of performance for that individual since the previous assessment.

4.3.3. Standardized Questionnaires

At the beginning of the study, we collected demographic information (participant age, gender, ethnicity, and whether they were living alone or not) and administered a chronotype questionnaire during one-on-one interviews with the participants in common rooms. We assessed participants’ well-being (depression, fatigue, and sleep quality) and lighting appraisal with questionnaires (see below) during the final week of each condition. Questionnaires were provided in English and/or Japanese language on iPads (6th generation) during one-on-one appointments with the same research personnel, in the participants’ homes or in common rooms. The participants were asked to complete the questionnaires on their own but were provided assistance from research personnel on a need basis. Assistance was provided in English and/or Japanese.

Sleep timing and chronotype were assessed with the ultra-short version of the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire (µMCTQ) [83]. The µMCTQ contains simple questions on the current timing of sleep and wake behaviour. As our participants have no workdays, we did not ask participants to report sleep patterns separately for work and free days. Instead, we asked them to report usual sleep patterns. Chronotype was assessed by means of mid-sleep.

Depression was assessed with the shortened form of the Geriatric Depression Scale [84], a 15-item self-report yes/no inventory in which participants rate the extent to which they have been bothered by various symptoms. Of the 15 items, 10 indicate the presence of depression when answered positively, while the rest indicate depression when answered negatively. Scores of 0–4 are considered normal, depending on age, education, and complaints; 5–8 indicate mild depression; 9–11 indicate moderate depression; and 12–15 indicate severe depression. The short form is more easily used by physically ill and mildly to moderately demented patients who have short attention spans and/or feel easily fatigued. It takes about 5 to 7 min to complete.

Fatigue was assessed with the short version of the Daily Fatigue Form [85]. The 7-item scale describes daily fatigue in the last day along a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Sample item: “How often did you feel tired?”

Sleep quality was assessed with one item from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [86]: “In the past month how would you rate your sleep quality?” on a 4-point scale from very good (0) to very bad (3).

Lighting appraisal was assessed with a seven-point Likert scale (0 = very unsatisfied, 3 = neutral, 6 = very satisfied): “How satisfied are you with the lighting?”, which was asked separately for the bedroom, living room, kitchen, and bathroom [48].

4.4. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were computed in SPSS version 25. Due to the small sample size (N = 14), we primarily used non-parametric statistical analyses as they are based on fewer assumptions (e.g., normal distribution). Correlations between variables were analyzed with Spearman’s rho and when comparing between experimental conditions, we performed related samples Wilcoxon signed rank tests. We used parametric tests to determine unique predictors of outcome variables by means of multiple regression and to compare conditions (within subject comparisons) while controlling for potential confounding variables (e.g., order of condition) by means of mixed design ANOVA. The significance level was set at α = 0.05. Due to a priori predictions of effect direction, we also report as statistical trends those cases in which p > 0.05 but < 0.1. Assuming an effect size (d) of 0.5 and power of 0.8, with α = 0.05, a priori power analyses with G*Power [87] estimated a required sample size of n = 35 for two-tailed predictions and n = 28 for one-tailed predictions.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2624-5175/2/4/40/s1, Table S1: Demographic statistics following random assignment into groups A and B; Table S2: Frequency of chronotype categories based on MCTQ assessed mid-sleep at the start of the study; Table S3: Sample mean and standard deviation of study variables; Table S4: Multiple regression predicting IV; Table S5: Multiple regression predicting IS; Table S6: Multiple regression predicting RA; Table S7: Multiple regression predicting processing speed; Table S8: Manufacturer tabulated spectra; Figure S1: Tabulated spectra at 2812 K (20:00–6:00), 3847 K (7:00), 5050 K (8:00–18:00) and 3446 K (19:00). Additional observation—concern for nighttime wandering; and the CIE S 026 α-opic toolbox outputs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J. and R.E.M.; methodology, M.J., R.E.M., T.L.-A.; software, M.J.; formal analyses, M.J.; investigation, M.J., resources, M.J. and R.E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.; writing—review and editing, R.E.M., T.L.-A.; visualization, M.J., R.E.M.; supervision, R.E.M.; project administration, M.J., C.S., F.F.; funding acquisition, M.J., R.E.M., T.L.-A., F.F. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from AGE-WELL NCE Inc., a member of the Networks of Centers of Excellence program, and funding from BC Hydro.

Acknowledgments

We thank BC Hydro and the Nikkei Senior Home for their support and commitment throughout the study. Special thanks go out to Cathy Makihara, Gina Hall, Tara Pagnottaro, Peter Kan, and our dedicated research assistants Stephanie U, Joanna Pater, Luce Calderon, Mark Laxton, Na Young Choi, Karina Thiessen, Bonnie Ng, April Ricafort, and Masaru Tomoda. Above all, we thank our lovely research participants for always welcoming us with open arms. T.L.-A. is a Tier II Canada Research Chair in Physical Activity, Mobility, and Cognitive Neuroscience.

Conflicts of Interest

M.J. is the founder of Circadian Light Therapy and scientific advisory board member at Fatigue Science. R.E.M. is an honorary scientific advisory board member at Circadian Light Therapy. C.S. works at BC Hydro, which partially funded this study. T.L.-A serves on the board of directors for the BC Brain Wellness Foundation Inc and the executive team of Synaptitude Brain Health Inc. (she does not receive personal fees for these roles). F.F. declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study or in the collection, analyses, and interpretation of data, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| SCN | suprachiasmatic nucleus |

| µMCTQ | ultra-short version of the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire |

| NIHTB-CB | National Institutes of Health Toolbox-Cognition Battery |

| RA | relative amplitude |

| IV | intradaily variability |

| IS | interdaily stability |

| CCT | correlated colour temperature |

| CRI | colour rendering index |

References

- De Lepeleire, J.; Bouwen, A.; De Coninck, L.; Buntinx, F. Insufficient lighting in nursing homes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2007, 8, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.S.; Kripke, D.F.; Gillin, J.C.; Hrubovcak, J.C. Exposure to light in healthy elderly subjects and Alzheimer’s patients. Physiol. Behav. 1988, 42, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancoli-Israel, S.; Kripke, D.F. Now I lay me down to sleep: The problem of sleep fragmentation in elderly and demented residents of nursing homes. Bull. Clin. Neurosci. 1989, 54, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ancoli-Israel, S.; Klauber, M.R.; Jones, D.W.; Kripke, D.F.; Martin, J.; Mason, W.; Pat-Horenczyk, R.; Fell, R. Variations in circadian rhythms of activity, sleep, and light exposure related to dementia in nursing-home patients. Sleep 1997, 20, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Roenneberg, T.; Kantermann, T.; Juda, M.; Vetter, C.; Allebrandt, K.V. Light and the human circadian clock. In Circadian Clocks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, C.; Garbazza, C.; Spitschan, M. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie 2019, 23, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.G.; Hankins, M.W. Circadian vision. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, R746–R751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencio, I.; Rodriguez, I.R.; Jiang, G.; Hayes, W.P.; Moreira, E.F.; Rollag, M.D. A novel human opsin in the inner retina. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattar, S.; Liao, H.W.; Takao, M.; Berson, D.M.; Yau, K.W. Melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells: Architecture, projections, and intrinsic photosensitivity. Science 2002, 295, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brainard, G.C.; Hanifin, J.P.; Greeson, J.M.; Byrne, B.; Glickman, G.; Gerner, E.; Rollag, M.D. Action spectrum for melatonin regulation in humans: Evidence for a novel circadian photoreceptor. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 6405–6412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brainard, G.C.; Sliney, D.; Hanifin, J.P.; Glickman, G.; Byrne, B.; Greeson, J.M.; Jasser, S.; Gerner, E.; Rollag, M.D. Sensitivity of the human circadian system to short-wavelength (420-nm) light. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2008, 23, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warman, V.L.; Dijk, D.J.; Warman, G.R.; Arendt, J.; Skene, D.J. Phase advancing human circadian rhythms with short wavelength light. Neurosci. Lett. 2003, 342, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, V.L.; Arendt, J.; Terman, M.; Skene, D.J. Short-wavelength sensitivity of the human circadian system to phase-advancing light. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2005, 20, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, H.R.; Lack, L.C. Effect of light wavelength on suppression and phase delay of the melatonin rhythm. Chronobiol. Int. 2001, 18, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, H.R.; Lack, L.C.; Kennaway, D.J. Differential effects of light wavelength in phase advancing the melatonin rhythm. J. Pineal Res. 2004, 36, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.J. Interacting influences of aging and Alzheimer’s disease on circadian rhythms. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 51, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charman, W.N. Age, lens transmittance, and the possible effects of light on melatonin suppression. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2003, 23, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddy, J.R.; Rollag, M.D.; Brainard, G.C. Pupil size regulation of threshold of light-induced melatonin suppression. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1993, 77, 1398–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, M.A.; Swaab, D.F. Living by the clock: The circadian pacemaker in older people. Ageing Res. Rev. 2006, 5, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brainard, G.C.; Rollag, M.D.; Hanifin, J.P. Photic regulation of melatonin in humans: Ocular and neural signal transduction. J. Biol. Rhythm. 1997, 12, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, V.L.; Skene, D. Impact of age on human non-visual responses to light. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2010, 8, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Someren, E.J.; Riemersma-Van Der Lek, R.F. Live to the rhythm, slave to the rhythm. Sleep Med. Rev. 2007, 11, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranah, G.J.; Blackwell, T.; Stone, K.L.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Paudel, M.L.; Ensrud, K.E.; Cauley, J.A.; Redline, S.; Hillier, T.A.; Cummings, S.R.; et al. Circadian activity rhythms and risk of incident dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older women. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 70, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers-Soeder, T.S.; Blackwell, T.; Yaffe, K.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Redline, S.; Cauley, J.A.; Ensrud, K.E.; Paudel, M.; Barrett-Connor, E.; LeBlanc, E.; et al. Rest-activity rhythms and cognitive decline in older men: The osteoporotic fractures in men sleep study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 2136–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musiek, E.S.; Bhimasani, M.; Zangrilli, M.A.; Morris, J.C.; Holtzman, D.M.; Ju, Y.S. Circadian rest-activity pattern changes in aging and preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, J.A.; Quante, M.; Godbole, S.; James, P.; Hipp, J.A.; Marinac, C.R.; Mariani, S.; Feliciano, E.M.C.; Glanz, K.; Laden, F.; et al. Variation in actigraphy-estimated rest-activity patterns by demographic factors. Chronobiol. Int. 2017, 34, 1042–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Someren, E.J. Circadian and sleep disturbances in the elderly. Exp. Gerontol. 2000, 35, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Feijter, M.; Lysen, T.S.; Luik, A.I. 24-h activity rhythms and health in older adults. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 2020, 6, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissová, K.; Bartoš, A.; Sládek, M.; Nováková, M.; Sumová, A. Moderate changes in the circadian system of Alzheimer’s disease patients detected in their home environment. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Someren, E.J.W.; Oosterman, J.M.; Van Harten, B.; Vogels, R.L.; Gouw, A.A.; Weinstein, H.C.; Poggesi, A.; Scheltens, P.; Scherder, E.J.A. Medial temporal lobe atrophy relates more strongly to sleep-wake rhythm fragmentation than to age or any other known risk. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2019, 160, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wams, E.J.; Wilcock, G.K.; Foster, R.G.; Wulff, K. Sleep-wake patterns and cognition of older adults with Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI): A comparison with cognitively healthy adults and moderate Alzheimer’s disease patients. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2017, 14, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luik, A.I.; Zuurbier, L.A.; Hofman, A.; Van Someren, E.J.; Tiemeier, H. Stability and fragmentation of the activity rhythm across the sleep-wake cycle: The importance of age, lifestyle, and mental health. Chronobiol. Int. 2013, 30, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Someren, E.J.; Kessler, A.; Mirmiran, M.; Swaab, D.F. Indirect bright light improves circadian rest-activity rhythm disturbances in demented patients. Biol. Psychiatry 1997, 41, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.S.; Tan, K.T.; Tay, L.; Wong, Y.M.; Ancoli-Israel, S. Bright light therapy as part of a multicomponent management program improves sleep and functional outcomes in delirious older hospitalized adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiro, M.G.; Plitnick, B.A.; Lok, A.; Jones, G.E.; Higgins, P.; Hornick, T.R.; Rea, M.S. Tailored lighting intervention improves measures of sleep, depression, and agitation in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia living in long-term care facilities. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancoli-Israel, S.; Gehrman, P.; Martin, J.L.; Shochat, T.; Marler, M.; Corey-Bloom, J.; Levi, L. Increased light exposure consolidates sleep and strengthens circadian rhythms in severe Alzheimer’s disease patients. Behav. Sleep Med. 2003, 1, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloane, P.D.; Williams, C.S.; Mitchell, C.M.; Preisser, J.S.; Wood, W.; Barrick, A.L.; Hickman, S.E.; Gill, K.S.; Connell, B.R.; Edinger, J.; et al. High-intensity environmental light in dementia: Effect on sleep and activity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishima, K.; Hishikawa, Y.; Okawa, M. Randomized, dim light controlled, crossover test of morning bright light therapy for rest-activity rhythm disorders in patients with vascular dementia and dementia of Alzheimer’s type. Chronobiol. Int. 1998, 15, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemersma-van der Lek, R.F.; Swaab, D.F.; Twisk, J.; Hol, E.M.; Hoogendijk, W.J.; Van Someren, E.J. Effect of bright light and melatonin on cognitive and noncognitive function in elderly residents of group care facilities: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008, 299, 2642–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, S.; Morgan, P.L.; Schlangen, L.J.M.; Williams, P.; Skene, D.J.; Middleton, B. Blue-enriched lighting for older people living in care homes: Effect on activity, actigraphic sleep, mood and alertness. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2017, 14, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.J.; Campbell, S.S. Physiology of the circadian system in animals and humans. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1996, 13, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiro, M.G.; Plitnick, B.; Roohan, C.; Sahin, L.; Kalsher, M.; Rea, M.S. Effects of a tailored lighting intervention on sleep quality, rest-activity, mood, and behavior in older adults with Alzheimer disease and related dementias: A randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2019, 15, 1757–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münch, M.; Schmieder, M.; Bieler, K.; Goldbach, R.; Fuhrmann, T.; Zumstein, N.; Vonmoos, P.; Scartezzini, J.L.; Wirz-Justice, A.; Cajochen, C. Bright light delights: Effects of daily light exposure on emotions, restactivity cycles, sleep and melatonin secretion in severely demented patients. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2017, 14, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancoli-Israel, S.; Martin, J.L.; Kripke, D.F.; Marler, M.; Klauber, M.R. Effect of light treatment on sleep and circadian rhythms in demented nursing home patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 50, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowling, G.A.; Hubbard, E.M.; Mastick, J.; Luxenberg, J.S.; Burr, R.L.; Van Someren, E.J. Effect of morning bright light treatment for rest-activity disruption in institutionalized patients with severe Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2005, 17, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shochat, T.; Martin, J.; Marler, M.; Ancoli-Israel, S. Illumination levels in nursing home patients: Effects on sleep and activity rhythms. J. Sleep Res. 2000, 9, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubekri, M.; Cheung, I.N.; Reid, K.J.; Wang, C.H.; Zee, P.C. Impact of windows and daylight exposure on overall health and sleep quality of office workers: A case-control pilot study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2014, 10, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, M.C.; Geerdinck, L.M.; Versteylen, M.; Leffers, P.; Meekes, G.J.; Herremans, H.; de Ruyter, B.; Bikker, J.W.; Kuijpers, P.M.; Schlangen, L.J. Patient room lighting influences on sleep, appraisal and mood in hospitalized people. J. Sleep Res. 2017, 26, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, G.W.; Reid, C.; Kaye, D.M.; Jennings, G.L.; Esler, M.D. Effect of sunlight and season on serotonin turnover in the brain. Lancet 2002, 360, 1840–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishima, K.; Okawa, M.; Shimizu, T.; Hishikawa, Y. Diminished melatonin secretion in the elderly caused by insufficient environmental illumination. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhofer, E.I.; Higgins, P.A.; Daly, B.J.; Burant, C.J.; Hornick, T.R. Hospital lighting and its association with sleep, mood and pain in medical inpatients. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1164–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.A.; St Hilaire, M.A.; Lockley, S.W. The effects of spectral tuning of evening ambient light on melatonin suppression, alertness and sleep. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 177, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiro, M.G.; Steverson, B.; Heerwagen, J.; Kampschroer, K.; Hunter, C.M.; Gonzales, K.; Plitnick, B.; Rea, M.S. The impact of daytime light exposures on sleep and mood in office workers. Sleep Health 2017, 3, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovell, B.B.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Gevirtz, R. Effect of bright light treatment on agitated behavior in institutionalized elderly subjects. Psychiatry Res. 1995, 57, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeisler, C.A. Perspective: Casting light on sleep deficiency. Nature 2013, 497, S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhi, N.; Thorne, H.C.; van der Veen, D.R.; Johnsen, S.; Mills, S.L.; Hommes, V.; Schlangen, L.J.; Archer, S.N.; Dijk, D.J. The spectral composition of evening light and individual differences in the suppression of melatonin and delay of sleep in humans. J. Pineal Res. 2012, 53, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitzer, J.M.; Dijk, D.J.; Kronauer, R.; Brown, E.; Czeisler, C. Sensitivity of the human circadian pacemaker to nocturnal light: Melatonin phase resetting and suppression. J. Physiol. 2000, 526 Pt 3, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg, T.; Kuehnle, T.; Juda, M.; Kantermann, T.; Allebrandt, K.; Gordijn, M.; Merrow, M. Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep Med. Rev. 2007, 11, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghiemstra, A.M.; Eggermont, L.H.; Scheltens, P.; van der Flier, W.M.; Scherder, E.J. The rest-activity rhythm and physical activity in early-onset dementia. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2015, 29, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, K.E.; Vitiello, M.V.; Larsen, L.H.; Prinz, P.N. Sleep/wake patterns in Alzheimer’s disease: Relationship with cognition and function. J. Sleep Res. 1995, 4, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiek, E.S.; Holtzman, D.M. Mechanisms linking circadian clocks, sleep, and neurodegeneration. Science 2016, 354, 1004–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; Musiek, E.S.; Hu, K.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Yaffe, K. Association between circadian rhythms and neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranah, G.J.; Blackwell, T.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Paudel, M.L.; Ensrud, K.E.; Cauley, J.A.; Redline, S.; Hillier, T.A.; Cummings, S.R.; Stone, K.L.; et al. Circadian activity rhythms and mortality: The study of osteoporotic fractures. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weldemichael, D.A.; Grossberg, G.T. Circadian rhythm disturbances in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 2010, 716453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nioi, A.; Roe, J.; Gow, A.; McNair, D.; Aspinall, P. Seasonal differences in light exposure and the associations with health and well-being in older adults: An exploratory study. HERD 2017, 10, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiro, M.G.; Hamner, R.; Higgins, P.; Hornick, T.; Rea, M.S. Field measurements of light exposures and circadian disruption in two populations of older adults. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 31, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stothard, E.R.; McHill, A.W.; Depner, C.M.; Birks, B.R.; Moehlman, T.M.; Ritchie, H.K.; Guzzetti, J.R.; Chinoy, E.D.; LeBourgeois, M.K.; Axelsson, J.; et al. Circadian entrainment to the natural light-dark cycle across seasons and the weekend. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantermann, T.; Juda, M.; Merrow, M.; Roenneberg, T. The human circadian clock’s seasonal adjustment is disrupted by daylight saving time. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 1996–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiro, M.G. Light, sleep and circadian rhythms in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2017, 7, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, D.S.; Zele, A.J.; Feigl, B.; Adhikari, P. The accuracy of artificial and natural light measurements by actigraphs. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 29, e12963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiro, M.G.; Hamner, R.; Bierman, A.; Rea, M.S. Comparisons of three practical field devices used to measure personal light exposures and activity levels. Light Res. Technol. 2013, 45, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, A.C.; Pawley, M.D.; Cheeseman, J.F.; Guesgen, M.J.; Steele, C.T.; Warman, G.R. Validating the use of wrist-level light monitoring for in-hospital circadian studies. Chronobiol. Int. 2011, 28, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitschan, M.; Stefani, O.; Blattner, P.; Gronfier, C.; Lockley, S.W.; Lucas, R.J. How to report light exposure in human chronobiology and sleep research experiments. Clocks Sleep 2019, 1, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CIE. CIE System for Metrology of Optical Radiation for ipRGC-Influences Responses to Light; CIE Central Bureau: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lichstein, K.L.; Stone, K.C.; Donaldson, J.; Nau, S.D.; Soeffing, J.P.; Murray, D.; Lester, K.W.; Aguillard, R.N. Actigraphy validation with insomnia. Sleep 2006, 29, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marino, M.; Li, Y.; Rueschman, M.N.; Winkelman, J.W.; Ellenbogen, J.M.; Solet, J.M.; Dulin, H.; Berkman, L.F.; Buxton, O.M. Measuring sleep: Accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of wrist actigraphy compared to polysomnography. Sleep 2013, 36, 1747–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigeon, W.R.; Taylor, M.; Bui, A.; Oleynk, C.; Walsh, P.; Bishop, T.M. Validation of the sleep-wake scoring of a new wrist-worn sleep monitoring device. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushida, C.A.; Chang, A.; Gadkary, C.; Guilleminault, C.; Carrillo, O.; Dement, W.C. Comparison of actigraphic, polysomnographic, and subjective assessment of sleep parameters in sleep-disordered patients. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Someren, E.J.; Hagebeuk, E.E.; Lijzenga, C.; Scheltens, P.; de Rooij, S.E.; Jonker, C.; Pot, A.M.; Mirmiran, M.; Swaab, D.F. Circadian rest-activity rhythm disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry 1996, 40, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, R.C.; Wagster, M.V.; Hendrie, H.C.; Fox, N.A.; Cook, K.F.; Nowinski, C.J. NIH toolbox for assessment of neurological and behavioral function. Neurology 2013, 80 (Suppl. 3), S2–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, K.; Krikorian, R.; Giovannetti, T.; Melendez-Cabrero, J.; Rahman, A.; Caesar, E.E.; Chen, J.L.; Hristov, H.; Seifan, A.; Mosconi, L.; et al. Utility of the NIH Toolbox for assessment of prodromal Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 10, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, C.N.; Natelson Love, M.C.; Triebel, K.L. Normal cognitive aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2013, 29, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotbi, N.; Pilz, L.K.; Winnebeck, E.C.; Vetter, C.; Zerbini, G.; Lenssen, D.; Frighetto, G.; Salamanca, M.; Costa, R.; Montagnese, S.; et al. The µMCTQ: An ultra-short version of the Munich ChronoType questionnaire. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2020, 35, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, J.I.; Yesavage, J.A. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence in the development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. J. Aging Mental Health 1986, 5, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou, C.; Schneider, S.; Junghaenel, D.U.; Broderick, J.E.; Stone, A.A. Measuring daily fatigue using a brief scale adapted from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®). Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).