3.3. Steady-Loading Noise and Forward-Flight Induced Unsteady-Loading Noise

Horizontal flight of a drone at small, negative pitch angle is addressed in this section as responsible for the onset of BLH and for the associated sound generation. Its effect when compared to hover is to involve a non-zero lateral fluid motion in the plane of rotation combined with an axial fluid motion normal to this plane. In absence of accurate prediction of the lift variations on a blade section, a crude estimate is provided by assuming a uniform oblique fluid motion through the rotor disk, with the angle

as shown in

Figure 1b and the velocity

. The latter is equal to the advancing speed and of opposite direction.

The blade cross-section of radius

r is assumed a flat-plate of chord

c inclined by the angle

with respect to the plane of rotation (rotor disk), parallel to the chord line of the true cross-section profile, as shown in

Figure 3. If the flight is assumed along the positive coordinate

X (

axis) for a counterclockwise rotating rotor, and if the considered blade element is on this axis at the origin of time, the instantaneous oncoming tangential and axial flow speeds on the cross-section are

and

, respectively. This leads to expressions for the relative speed at rotor inlet

and the associated angle of attack

as

noting that the relative spanwise velocity component does not enter the problem.

A cruder analysis assuming a negligible pitch angle

would lead to

and

, providing a first estimate of the fluctuations when the actual pitch angle is unknown. At very low frequencies, the lift variations induced on the blade section can be assessed from a quasi-steady approximation and from the relation between angle of attack and lift coefficient

. Based on the theoretical value

of Cauchy’s potential theory [

24] and assimilating the airfoil to a flat plate, the instantaneous sectional lift simply reads

where

c and

ℓ are the chord and span of the considered blade segment, and

is the density of air. Partly because the advancing ratio

is small in practice, the time variations of the lift are close to sinusoidal. This is confirmed by deriving the differential

with

As a result, the onset of the dominant BLH orders

is expected, with weaker amplitudes at orders

. To check that point, estimates of the coefficients

of the Fourier series of

, not shown for conciseness, have been calculated from the definition

The mean value associated with steady-loading noise was found typically between 7 and 10 times higher than the BLH amplitudes , whereas higher harmonics were negligible. This crude approximation probably overestimates the relative contribution of steady-loading noise because it ignores the mean-flow gradients, in particular the induced axial flow in the vicinity of the rotor disc. Yet it provides an easy way of comparing the orders of magnitude of steady-loading and unsteady-loading noise.

Equation (

2) states that steady-loading noise is associated with the radiation-efficiency factor

, with

and

, plotted in

Figure 4a as a function of

n in equivalent decibels. The factor is an increasing function of

X. It is clear that this noise is poorly radiating at low blade-tip Mach numbers for quite large numbers of blades. Yet it becomes significant at higher Mach numbers and/or for small blade numbers, especially if flow distortions are small. As explained above, operation with non-zero lateral flow primarily generates the blade-loading harmonics of orders

that trigger the Bessel functions

as efficiency factors. These two are also plotted in

Figure 4b,c to illustrate the discussion.

is to multiply by the steady force

on the considered blade segment, whereas the other two are to multiply by the BLH

and

, both having the same order of magnitude. The first outcome from the figure is that the factor

can be neglected, whereas the factor

must be considered because it exceeds that of the steady loading, especially at low Mach numbers at the BPF. The drone D1 addressed by Misiorowski et al. [

18] corresponds to the indicative value

reported as the red data in

Figure 4. In this case, the weighting factor of the BLH

is 20.9 dB higher than that of the steady load at the BPF. As a result, unsteady-loading noise is expected to exceed steady-loading noise at that frequency as soon as the lift variations reach about 16% of the steady lift. Strictly speaking, the steady-loading possibly radiates a noticeable sound at the blade-tip Mach number of 0.18 and for a two-bladed rotor. This is emphasized by the red dots in

Figure 4a. However, the rate of decrease is so fast that the radiation efficiency at 2PBF is already 21.4 dB lower than at the BPF. This suggests that, in practice, steady-loading noise is probably overwhelmed by unsteady-loading noise from the second tone to higher harmonics, even with quite moderate distortions.

For comparison, different parameters corresponding to the quadrotor vehicle analyzed with flow computations by Yoon et al. [

19] can also be assessed from the same Bessel-function plots. The blade number in the reference is

and the blade-tip Mach number about 0.7. Only values of

n that are multiples of 3 and the three curves for

are selected in this case. They are shown in blue in the figure. Now the rate of decrease of the curves is much slower. The relatively large values of the function

make steady-loading noise expected as a very significant contribution, for several BPF harmonics. Typically the decrease is only of 1.4 dB between the BPF and 2BPF, and about 7 dB between the BPF and 4BPF. Furthermore the weighting factor

acting on the BLH of order

is 8.2 dB higher than the factor

. This stresses that for the same rate of unsteady loading the higher speed corresponds to a smaller difference of radiation efficiency between steady-loading noise and unsteady-loading noise.

In fact, the true forward flight of a quadrotor produces more complex flow and lift fluctuations, with different BLH amplitudes and orders. This is why attention is paid now to computed flow results on a real drone configuration, and the way they can be used for more accurate sound predictions. The quadrotor investigated by Misiorowski et al. [

18] is selected as an example because all required parameters can be found in the reference. The configuration, approximately defined as D1 in

Table 1 and shown in

Figure 1b, includes the full quadrotor but neither the struts nor the main body of the drone. Therefore the flow blockage and the associated distortions are ignored, which means that only unsteady loads caused by the oblique relative flow are captured. Results from an incompressible Detached-Eddy Simulation were obtained for an advancing flight speed of 10 m/s and a pitch angle of

. Iso-contours of the sectional thrust coefficient

(per unit span) in the rotor plane as computed in the reference are roughly reproduced in

Figure 5a, for the starboard front rotor only. Though a similar analysis could be performed for the rear rotor, it is not essential for the present purpose. Indeed the test is essentially aimed at ranking steady-loading noise and unsteady-loading noise for a rotor in side-flow, on the one hand, and both rear and front rotors have similar qualitative flow features, on the other hand [

18]. The view is from above and the rotor is spinning clockwise. The symmetric-image distribution would hold for the portside rotor spinning counterclockwise. The indicative values provided in the figure point high-thrust and low-thrust areas over the rotor disk, corresponding to the advancing and retreating blades, respectively. This is responsible for substantial lift variations on the blades and associated unsteady-loading noise. Indeed, angular variations on the disk correspond to time variations on the blades. Circular cuts of the isocountour-map for ten evenly spaced radii

,

, have been considered to compute the Fourier coefficients of the sectional lift, thus the BLH, according to the definition

In this operation the angle

is followed in the clockwise direction to be in accordance with the time correspondance. The discrete spectrum of the

coefficients is displayed as a bar-graph in

Figure 5b.

corresponds to the averaged thrust of each blade segment, thus the source of the steady-loading noise. The bar-graph evidences thrust harmonics of orders ± 1 of about 20% to 30% of the mean thrust, which makes unsteady-loading noise an efficient contribution. This is substantially more than the aforementioned rough estimates based on the quasi-steady approximation. Therefore, the latter could be used to infer the minimum level of BLH expected in forward flight, in absence of more accurate information about the flow. Anyway, the results confirm the recognition of the modes ± 1 as the typical signature of forward flight. Two periods of the unwrapped angular profiles of the sectional lift at the ten extraction radii are plotted in

Figure 6 for completeness. The profiles of the inner area (cuts 1 to 5) are plotted in black and gray; they exhibit a monotonic increase. The profiles of the outer area (cuts 6 to 10) are plotted in pink and colors; they have a substantial plateau of nearly equal minimum values. The maximum lift is found at the cuts 6 and 7. These profiles depart substantially from the quasi-sinusoidal shape expected from the simple analysis based on Equation (

6). This is mainly attributed to the aerodynamic coupling between the four rotors and to the detailed features of the induced axial flows, ignored in the analytical model but reproduced in the numerical simulation.

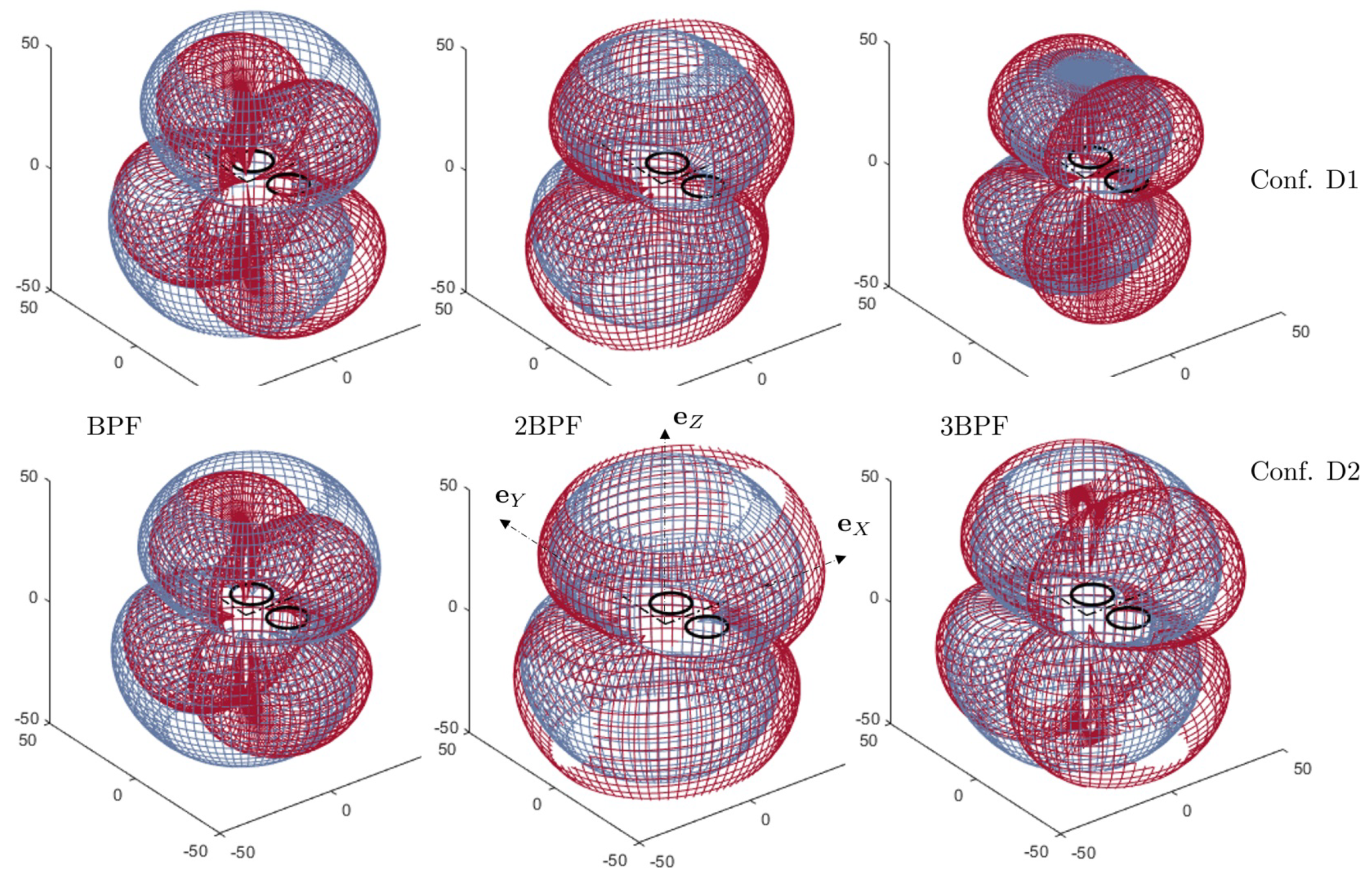

Typical sound predictions made with the present analytical model are reported in

Figure 7 in terms of three-dimensional directivity patterns. They are based on a source-mode expansion at the ten aforementioned radii, fed with the complex-valued blade-loading harmonics associated with the bar-graph in

Figure 5b. The radius of the observation sphere is 10

, with origin at the quadrotor center-point. Therefore, the observer is in the acoustic far field, in the sense that the distance multiplied by

is larger than the wavelength at the BPF, around 150 Hz, but not in the geometric far-field with respect to the general dimensions of the quadrotor. Yet, the basic directivity lobes are already well structured. All radii are taken into account and only the pair of contrarotating front rotors is considered. Indeed, the aft rotors radiate at different frequencies because of their different rotational speed. The test is primarily aimed at comparing the relative amplitudes of the acoustic signatures of the steady loading on the blades and of the lift fluctuations due to forward motion with negative pitch angle. Furthermore, both rotors are synchronized in the test with a zero phase shift (upper plots) and with a phase shift of half a blade passage (lower plots). In the first case, both rotor configurations are symmetric images of each other with respect to the vertical mid-plane of the quadrotor, as well as their isolated acoustic fields. In the second case, any blade-tip passage of one rotor at the minimum distance of both tip circles takes place between two passages of the other rotor. The directivity diagrams are plotted as interpenetrating meshed surfaces for a better illustration of the differences between the sound field of a single rotor and that of the pair of rotors. They exhibit main lobes separated by extinction angles.

The directivity at the BPF is shown for the steady-loading noise only in the left plots and for the total noise in the middle plots. Obviously, the former is much lower than the latter, except at

angles approaching

. Steady-loading noise therefore contributes to the horizontal radiation for normal operating conditions. It could contribute, for instance, to the sound received on building walls during urban operations. In other directions, the sound is essentially attributed to unsteady loads on the blades. The amplitude of steady-loading noise decreases dramatically at higher harmonics. This is why only the total-noise directivity, almost equal to that of the unsteady-loading noise, is shown for the harmonic 3BPF in the right plots; it exhibits a larger number of lobes as an effect of higher non-compactness. A general feature of the tonal noise of a single rotor in arbitrary distortion is the dominant radiation around the rotational axis, associated with the symmetric mode fed with the BLH

. Unlike steady-loading noise, unsteady-loading noise preferentially radiates vertically. The synchronization with zero phasing reinforces the sound around the vertical plane with respect to what the radiation of a single rotor would be. In contrast, the half-blade passage phasing leads to the cancellation of the sound in the vertical plane aligned with the forward flight direction for odd harmonic orders, as expected, at the price of a more efficient radiation at oblique angles. The outcomes of those sample results are twofold. Firstly, thrust and forward-flight associated contributions to the total sound have different radiating properties. Secondly, the former is significant only at lowest frequencies. By virtue of the weaker loudness at low frequencies in terms of the A-weighted decibels, unsteady-loading noise clearly dominates. Yet, in view of the test case reported in

Figure 7, and apart from the different directivity patterns, steady-loading noise at the BPF is only about 10 dB below unsteady-loading noise. This suggests that it could dominate in hover, at least if no other mean-flow distortion is considered. However, such distortions can also be generated by supporting struts, as discussed in

Section 3.4.

For a complementary view of basic interference features of the sound field, maps of the instantaneous acoustic pressure in the rotor plane

and in the neighborhood of the pair of rotors are shown in

Figure 8. Over-pressures and under-pressures are shown in red and blue, respectively, green corresponding to the undisturbed static pressure. Arbitrary but comparable color scales are used, in the range

for steady-loading noise and in the range

for the total noise. Only the BPF is illustrated, for conciseness. The first two sub-plots illustrate the radiation of the port-side rotor only (the rotors are featured as white circles) for the steady-loading noise in

Figure 8a and the total noise in

Figure 8b. The expected mode 2

, with clearly formed spiral branches, is recognized in the first case. A mode complex pattern is found in the second case, with a dominant mode

fed by the BLH of order

. Steady-loading noise maps of the pair of rotors are shown for zero phasing and half-blade passage phasing in

Figure 8c,d, respectively. In the case of zero phasing, the rotors are perfect symmetric images of each other, as well as the associated wavefront patterns. Therefore, the map is again symmetric with respect to the

axis. In the case of half-blade passage phasing, the sound pressure is zero at any time along the

axis, with out-of-phase pressure fluctuations on both sides of the axis. In both cases, the four lobes seen on the directivity diagrams in

Figure 7 (left side) are already formed at quite short distances from the center of the quadrotor, with local distortions in the very vicinity of the rotors. Finally, similar maps are plotted for the total noise in

Figure 8e,f, with, again, symmetry in the case of zero phasing, and cancellation in the vertical plane aligned with the flight direction in the case of half-blade passage phasing. Qualitatively, in view of the color scales, the amplitude of the total noise is about three times higher than that of the steady-loading noise.

3.4. Generic Potential-Interaction Noise Model

A single rotor-strut system of a drone is similar to the technology of the tail rotor of a helicopter. Indeed, the transmission shaft radially positionned just downstream of the rotor for the latter plays the same obstruction role as the strut for the former. A strong tonal noise is generated in this case, for which an analytical model has been proposed by Roger et al. [

23,

25], as follows. The distorted flow around any shaft cross-section is assimilated to the two-dimensional potential flow around a circle [

26]. Exact analytical expressions are deduced for the Fourier coefficients of the upwash (velocity fluctuation normal to the chord) experienced by the blades when crossing the distortion periodically, by complex-residue calculations. The expressions, not reproduced here for conciseness, have been implemented for a single rotor in both cases D1 and D2, assuming that the relative flow downstream of the blades is aligned with the local chord line, for simplicity. This defines the angle of the flow relative to the strut, of speed

, accordingly. The results for the angular upwash profiles

at the 10 radii previously defined are reported in

Figure 9 and those for the associated Fourier coefficients

in

Figure 10. Repeated predictions previously performed with the exact analytical solution confirmed the relevance of an empirical best fit proposed by Roger and Kucukcoskun [

23]. According to this fit, the complex-valued distortion harmonics are approximated as

where

are adjustable parameters, functions of the configuration. The empirical fit allows estimating the BLH in any architecture for which a propeller operates in close vicinity of a radial strut or arm once the latter is assimilated to an equivalent cylinder of circular cross-section. In the present application, the simplified expression, Equation (

8), has been found to deviate from the exact results for very attenuated distortion profiles, and to be quite relevant for pronounced ones. It agrees qualitatively with the alternately positive and negative values illustrated in

Figure 10, especially for the configuration D2. Therefore, it could become the basis of a simplified formulation for extensive impact studies, provided that the coefficients are tuned beforehand on some typical test cases. Such an investigation is beyond the scope of the present work.

In configuration D1, the strut is quite thin and far away below the rotor disk, leading to a priori negligible potential distortion at the rotor position. Indeed, the equivalent radius

a is of about

and the interaction distance of about

. The corresponding weak upwash is illustrated in

Figure 9a. In contrast, configuration D2 features quite thick struts at shorter interaction distance, which generate a strong potential distortion. The corresponding upwash plotted in

Figure 9b is about 10 times larger. The azimuthally averaged value of the upwash

contributing to the thrust-associated coefficient

of

Section 3.3 is not considered in the present prediction only aimed at assessing unsteady-loading noise. Furthermore, the decrease of the amplitude

with the harmonic order

s is slightly faster in configuration D1.

In view of the chordwise compactness of the blades (chord length smaller than the acoustic wavelengths) and of the moderate Mach numbers (about 0.2), the sectional BLH can be approximately inferred from Sears’ theory, leading to the expression

, where

stands for the classical Sears’ function [

14] and

c for the chord length of the blades at the radius

r.

Typical directivity patterns of potential-interaction noise as deduced from the upwash profiles in

Figure 9 are shown in

Figure 11, for configurations D1 and D2 at the same rotational speed of 4058 rpm. Both differ in terms of amplitudes. Unexpectedly, the sound at the BPF is of similar level in both cases, in spite of the much closer obstruction caused by the struts in configuration D2. In fact, the larger size in configuration D1 balances the weaker distortion. The difference in radiated noise is more pronounced at higher BPF harmonics, especially at 3BPF for which configuration D2 is much louder, as expected from its general design. A shorter rotor-strut distance induces stronger and more impulsive lift variations on the blades, thus a lower decrease of the BLH envelope, which also makes more sound expected at higher BPF harmonics.

Because both the potential distortion and the forward-flight effect generate BLH of all orders, they have similar radiating features. For a single rotor, the sound is again mainly radiated vertically, with a minimum around the rotational plane. Synchronization with zero phasing reinforces this trend, whereas half-blade passage phasing forces radiation at oblique directions and leads to sound cancellation in the vertical plane aligned with the flight direction.