Abstract

This paper examines housework reallocation during China’s stringent pandemic lockdowns in 2020, where individuals were homebound and job-free while employment status remained unchanged. Utilizing a mixed-method approach, it analyzes 1669 surveys and 100 interviews to understand changes in domestic labor patterns and the underlying reasons. The findings indicate that men increased their participation in grocery shopping but decreased in cooking, cleaning, and laundry during the lockdown. This gender-task pattern was mirrored in multi-generational households, where younger family members often took on these tasks. The reasons articulated for these shifts predominantly converged around the ‘doing gender’ theory. Women, particularly those working full-time, had more time to engage in household chores. Men, while also having more available time, predominantly focused on grocery shopping, a task that gained masculine connotations during the lockdown. Factors such as perceived differences in household labor quality, difficulty delegating housework, and reduced workload led to women’s increased involvement and specialization in domestic tasks. The study challenges the notion that economic factors are the primary drivers of gender-based division of housework. Instead, it suggests that ingrained gender norms continue to dictate domestic roles, as evidenced during the lockdown period devoid of usual economic and time pressures.

Keywords:

housework division; COVID-19 pandemic; lockdowns; China; time availability; gender; generation 1. Introduction

Research on housework division excluding childcare (Sullivan 2013) has surged since the COVID-19 pandemic began. The pandemic and following unprecedented lockdowns have been viewed as an exceptional setting as genders needed to adjust to the new circumstances that were different in multiple dimensions of the work–family interface. Studies from several developed countries found mixed results on whether the pandemic caused a fairer division of housework between genders. In Italy, women took on more housework than men (Del Boca et al. 2020), while in Canada and Spain, the quarantine led to a more equal distribution as individuals had more available time to respond to domestic demands (Farré et al. 2020; Shafer et al. 2020). The situation in the US and UK presented a complex picture; some studies suggested a more balanced redistribution of housework, while others indicated a less equitable division, often exacerbated by childcare responsibilities (Carlson et al. 2021; Chung et al. 2020; Dunatchik et al. 2021; Sánchez et al. 2021; Sevilla and Smith 2020). Some studies from developing countries showed that lockdowns reinforced traditional gender roles in domestic responsibilities, with genders specializing in different types of housework (e.g., Obioma et al. 2022). However, little is known about how families adapted in China, where the most stringent lockdown measures were ever imposed. A notable exception is the recent study by Xu et al. (2022), which examined the transition of housework duties between generations within various household arrangements.

In response to the emergence of COVID-19, China implemented strict measures. Wuhan was on lockdown since 23 January 2020, followed by most cities and towns through (at least) February in the form of Spring Festival holiday extensions. All provincial units (including autonomous regions and direct-administered municipalities) in mainland China responded with Tier-1 measures, the highest level prescribed by the government, including suspending work, business, school, and gatherings (see Appendix A Table A1).

Unlike most countries’ lockdowns that only suspended public activities, China’s Tier-1 lockdowns in early 2020 featured a “closed-off management” system that directly impacted both public and private spheres (Liu et al. 2021). In this setup, each residential unit—whether a residential compound or a village—maintained just a single open gateway. Community workers monitored every resident’s temperature, face coverings, and entry/exit passes, effectively regulating movement around the clock. Residents were given quota-controlled permission to leave the unit (for example, one person per household every one or two days), with some regions even imposing a complete ban on leaving. Instead, residents could pick up deliveries from designated areas within the communal unit. In the most restricted areas, assigned community workers delivered goods to residents in need.

In addition to physical confinement, the suspension of productive activities was another aspect of China’s lockdowns. Unlike in other countries where teleworking was an option, the timing of China’s lockdowns coincided with the traditional Spring Festival holiday, a period when most production activities are already halted. These lockdowns ranged in duration from 27 to 99 days, with the average being 43 days (see Appendix A Table A1) for more details.

Consequently, China’s lockdowns had a fairly uniform impact on domestic lives, effectively isolating a vast majority from their usual market work. Estimates suggest that at the end of January, which coincided with the Chinese New Year, approximately 90% of the workforce was not engaged in active employment. Even in the subsequent months of February and March, only about 36% and 28% of people, respectively, returned to work (Public Books 2020). This scenario created an unusual setting in which a large majority of the population found themselves confined to their homes without employment for an extended duration. During this period, individuals either continued to receive income from their employers or relied on savings accumulated from previous employment, thereby sustaining the existing economic balance between genders.

Previous discussions on housework division, including those during the pandemic, have largely been grounded in an economic framework, which posits that domestic activities are essentially a byproduct of productive relationships. Market work assumingly determines the time and economic resources that genders have available for negotiating household responsibilities and affects venues for gender display. However, the unique circumstances of China’s stringent lockdowns, framed as an emergency state response, offer a different context for this study.

During these lockdowns, the economic variables that typically influence household dynamics were temporarily held constant owing to the suspension of most productive activities during a national holiday. Consequently, this setting—where individuals were confined to their homes and largely disengaged from employment—presented an unparalleled opportunity to examine gender interactions within households. By considering the pandemic lockdowns as an external shock that froze productive activities while preserving economic status, the division of domestic labor among confined, job-free individuals can be scrutinized in a novel light.

In this article, I explore the effects of China’s 2020 pandemic lockdowns on the gender-based division of household labor. Utilizing the unique conditions created by these strict lockdown measures, I examine shifts in the allocation of housework responsibilities across genders and generations and delve into the underlying reasons for any observed changes. The paper is organized as follows: I begin with a succinct overview of the theoretical framework surrounding the gender division of housework, along with an examination of how this division has evolved during the global pandemic. Subsequently, I outline the distinct cultural context that characterizes domestic labor divisions in China and describe the adjustments made to the survey methodology to suit this context. This is followed by a presentation of the sample distribution and the data analysis techniques employed. The final sections offer a discussion of the results, culminating in a summary of the key findings, their broader implications, and the study’s limitations.

2. Gender Division of Housework

The division of housework between genders can be explained through three determinants: money, time, and gender. Prevailing views suggest that either money or time plays a role in perpetuating inequality from the productive to the reproductive sector. These views contend that women perform more housework because they earn less in the labor market and have less bargaining power (Lachance-Grzela and Bouchard 2010; Lyonette and Crompton 2015) or have more idle time available (Bianchi et al. 2000; Gough and Killewald 2011; van der Lippe et al. 2018). On the other hand, the gender-based approach highlights that gender roles and expectations have a structural impact on behavior. The act of performing and not performing housework is, in and of itself, a manifestation of ‘doing gender’ (Bittman et al. 2003; West and Zimmerman 1987).

Recent decades have seen an increasing emphasis on the gender-based approach, as women continue to shoulder the majority of housework despite their increased economic resources and reduced time availability resulting from women’s growing participation in market work (Bünning 2020; Hook 2017; Meil et al. 2023; Presser 1994; van der Lippe et al. 2018). Indeed, housework has historically been constructed as women’s work, and performing or avoiding it can be a means of displaying gender (Brines 1994) or neutralizing deviance from gender expectations (Bittman et al. 2003; Greenstein 2000; Sullivan 2011) accordingly.

Although the distribution of economic and time resources may change, the gender structure remains primarily stable, even though ideological changes may occur over time (Risman 2011; Sullivan et al. 2018). Gender relations permeate society’s individual, interactional, and institutional dimensions, which should be considered when examining the relationship between gender and non-gender-based factors, such as economic resources and time (Risman 2004). Therefore, even though time and money appear gender-neutral, their values may still be gendered due to their different denotations between women and men.

The proliferation of research has further intensified the debate surrounding the root causes of the gendered division of household labor, with many empirical tests inadvertently subject to spuriousness due to the intricate nature of the subject (see Bianchi and Milkie 2010 for a review). For example, endogeneity biases are a concern in empirical tests when differentiating between the effects of time and money or gender and time/money because time availability is highly correlated with income (Jenkins and O’Leary 1995), and individuals may forgo higher-paying, time-consuming jobs to prioritize family commitments (Hook 2017). For this reason, the COVID-19 lockdowns have been perceived as a unique opportunity to observe how an external shock has impacted housework divisions and to test which determinants are more influential in this context.

3. Housework Reallocation during the Pandemic

Research on the division of household chores during the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that the crisis has significantly impacted household dynamics and the distribution of household work. Studies have primarily focused on two sources of change: the increased available time (e.g., Hipp and Bünning 2021; Meraviglia and Dudka 2021) and domestic insourcing (e.g., Collins et al. 2021; Hank and Steinbach 2021) during the period.

The effects of changes in time arrangements as the primary driver of the new housework divisions have yielded mixed results regarding gender (in)equalization. For example, a comparison of two representative samples of Italian working women before and after the onset of the pandemic found that over two-thirds of women and 40% of men spent more time doing housework. Women’s workload increased independently of their partner’s working arrangements, whereas men contributed more only when their partners continued to work (Del Boca et al. 2020). Farré et al. (2020) found that although men increased their participation in housework in a Spanish sample, the extent was slight compared to the burden that fell on women. In contrast, studies from North America and Australia suggest a more gender-egalitarian division of household chores during the initial months of lockdowns, with men contributing more while having more time at home (Carlson et al. 2021; Craig and Churchill 2021; Shafer et al. 2020). However, this equilibrium is disrupted when childcare is factored in. The introduction of childcare responsibilities tends to tilt the balance of domestic labor toward women, further intensifying their workload (Dunatchik et al. 2021).

The impact of domestic insourcing on the gendered division of housework has been more consistent as women have been found to take on more of the extra domestic work while the service sector was closed. Previous studies suggest domestic outsourcing has been a major factor in gender convergence in household activities since this century, significantly reducing women’s housework time (Sullivan et al. 2018). However, with the pandemic leading to unprecedented de-institutionalization, families experienced increased domestic responsibilities when restaurants and laundry services closed, and household servants were discontinued for personal precautions and/or policy prohibitions. This might increase women’s household responsibilities, particularly for those who previously benefited from domestic outsourcing (Hank and Steinbach 2021). As a result, women took on three times more of the increased housework than men in 2020 (United Nations 2020).

While research from around the world has effectively informed our understanding of the pandemic’s gendered impacts, most samples contain changes in paid work arrangements that complicates establishing a direct causal link to changes in the gender division of housework. The pandemic’s impacts on employment, particularly affecting women’s likelihood of job loss or transition to telecommuting, raises questions about how these changes in employment status relate to housework responsibilities (Adams-Prassl et al. 2020; Alon et al. 2020; Azcona et al. 2020; Hupkau and Petrongolo 2020; Kashen et al. 2020). Some studies suggest that women spontaneously (albeit unwillingly) reduced their paid work hours or quit jobs to respond to the increased domestic demands during the pandemic (e.g., Andrew et al. 2022; Craig and Churchill 2021; Mooi-Reci and Risman 2021), while others argue that women’s disproportionate increase in domestic contributions was a result of their higher job volatility that caused them to spend more time at home than men during the crisis (e.g., Biroli et al. 2021; Farré et al. 2020; Hayes and Lee 2023; Reichelt et al. 2021; Sevilla and Smith 2020). On the flip side, men experiencing job loss often grapple with heightened emotional stress linked to societal expectations of masculinity and breadwinning, potentially leading to a return to traditional household labor roles (Andrew et al. 2022). Gender dynamics are also evident in remote work scenarios, with male-dominated occupations being more conducive to remote arrangements, offering men greater flexibility. In contrast, women in the service industry, which is less adaptable to remote work, face challenges (United Nations 2020), potentially reducing the gender gap in domestic labor as remote work permits more time at home (Farré et al. 2020).

The pandemic’s economic shifts thus significantly influence the gender division of household chores. This aligns with previous research, suggesting that the disparate impact of employment changes on gender largely dictates domestic labor division (Berghammer 2022; Craig and Churchill 2021; Del Boca et al. 2020; Hayes and Lee 2023; Reichelt et al. 2021). However, can economic factors be controlled in order to study the nuances of domestic labor divisions? China’s strict lockdowns spatiotemporally confined people for a relatively long time while many productive activities were temporarily suspended. Despite this, most people’s economic status and resources remained relatively stable. This situation rendered genders ostensibly equally available for household chores, independent of employment status. Furthermore, the closure of most public amenities and transportation systems during this period may have redefined the physical landscape in which gender roles were expressed through different housework practices.

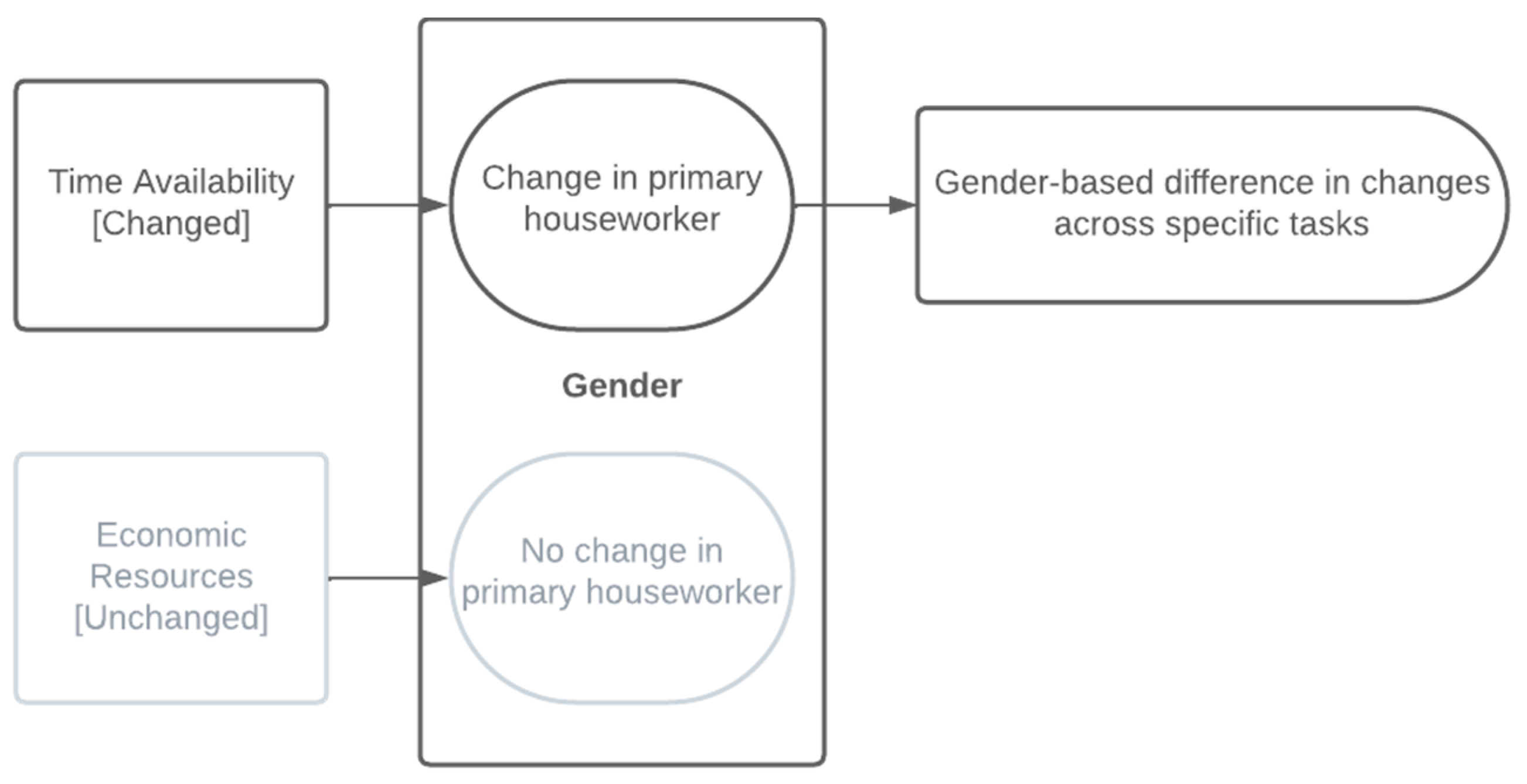

If economic resources were the dominant factor affecting the division of household labor, we would expect to see minimal changes between genders in this context. In other words, any observed changes in the distribution of domestic responsibilities can be more clearly attributed to available time variations (see Figure 1). Gender, furthermore, may serve as a critical determinant in how these task redistributions manifest differently among men and women across different types of chores.

Figure 1.

The analysis logic model.

Therefore, comparing household labor divisions before and during China’s stringent lockdowns offers a unique opportunity for a more isolated examination of the effects of changes in available time and de-institutionalization without the confounding variables of employment status changes.

4. Housework Division in the Chinese Context

Theories on housework division have primarily been developed and tested in advanced Western contexts, where the nuclear family structure is a norm. However, applying these models to places where intergenerational co-residence is common can be problematic. In China, for instance, over 67% of parents aged 65 and older lived with their adult children in 2005 (Zeng and Xie 2014). If including proximate residence, the figure rises to over 80% of conjugal households in a nationally representative sample in 2010 (Gruijters and Ermisch 2019). Co-residence may have been even more common during the lockdown, given the family reunion tradition during the Spring Festival.

The involvement of older generations, residing either together or nearby, substantially alters the domestic labor dynamics for younger ones, contingent upon the elders’ life course stage, such as offering assistance during health or needing support during sickness or old age (Cheng 2018; Gruijters and Ermisch 2019). By excluding extended family members and focusing only on the spouses’ division, existing methods may omit crucial or primary houseworkers and result in biased findings. However, involving more family members in the study can exponentially increase the complexity of the housework division, making the research more challenging. Therefore, exploring housework division effectively and efficiently in the Chinese context may require adapting the existing methods to account for these features.

4.1. Intergenerational Living and Housework

While a growing body of the literature has examined the impact of intergenerational living arrangements on housework division, most studies still focus solely on the within-couple division of domestic labor, treating the presence of extended families as either a control or explanatory variable (e.g., Craig and Powell 2017; Spitze and Ward 1995). Hu and Mu (2021) investigated the effect of intergenerational living on the spousal housework division in China. However, due to data limitations, they did not explicitly examine the gender of the actual houseworker if it was someone other than the married couple. Although they acknowledged the gender significance of senior family members, it was inferred from changes in the couples’ housework hours. The lack of examination of the extended family’s labor division hinders our understanding of intergenerational gender roles in household work.

4.2. Generational and Gender Differences

In the context of the expanded household structure, the division of housework can be complicated by generational and gender differences related to crucial factors, such as gender role attitudes and workforce participation. This is especially true in China, a country that has experienced significant economic and social changes in recent decades. On the one hand, Confucianism has ingrained a hierarchical social order that respects male superiority culturally (e.g., patrilineality) and structurally (e.g., patrilocality) (Johnson 1983). As a result, Chinese and other East Asian women carry a higher percentage of housework compared to their Western counterparts (Kan and Hertog 2017; Kim 2013; Qian and Sayer 2016).

On the other hand, gender parity has been promoted in China since the establishment of the communist state in 1949, with an emphasis on equalizing property rights (e.g., ownership, heirship) and marriage practices (e.g., monogamy, rights to divorce) to mobilize women into the workforce. Women’s paid employment has been considered a socialist achievement, with paid employment being the norm in China for both sexes across classes and generations. Despite this, the revolution did not address the cultural and structural aspects of the patriarchal system (Gruijters and Ermisch 2019). As a result, since the early 1990s, China’s adoption of neoliberalism has widened gender gaps in labor force participation and pay, with women disproportionately affected by the withdrawal (e.g., employment-based creches) or privatization (e.g., from the state- to employer-funded maternity leave) of socialist welfare provisions. The participation of women in China’s labor force has seen a notable decline since 1990, a trend that runs counter to advancements in gender equality observed in many other countries over the same period. According to data from the International Labour Organization (2021), the gap in labor force participation rates between men and women in China has widened from 9.4 percentage points in 1990 to 14.2 percentage points in 2019. Likewise, the gender pay gap has also deteriorated: in 1988, women earned 86.3% of what men earned, but this ratio dropped to 76.2% by 2004 (He and Wu 2018).

Given such a historical context, intergenerational co-residency inevitably comprises cohorts with distinct gender role attitudes, working experiences, and bargaining resources in the domestic labor division. Older individuals typically harbor conservative gender ideologies, yet de-gendering is also noticed among seniors. Silver (2003) suggested that as individuals progress into their third (60–84 years) and fourth stages (85+ years) of life, traditional gender expectations in everyday life often soften. This weakening is associated with integrating feminine and masculine traits due to biopsychological and socioeconomic shifts (e.g., retirement, dependency). This transition is more pronounced in retired men, who face greater losses in power, income, status, public recognition, and family authority than their female counterparts. Supporting this, research shows that men tend to increase their household responsibilities more than women as they age (Verbrugge et al. 1996). Goh’s (2011) ethnographic study found a similar shift in urban Chinese families, with grandparents yielding to parents in child discipline and taking on more chores to alleviate pressure on dual-income couples, challenging the traditional Confucianist hierarchy and highlighting seniors’ reduced power.

5. Methods and Data Collection

5.1. Research Design

This study employs the qualitative method proposed by Lyonette and Crompton (2015) to examine the primary responsibility for routine housework types, including grocery shopping, cooking, cleaning, and laundry (Coltrane 2000; Crompton and Lyonette 2011), before and during the initial COVID-19 lockdown.1

While retrospective inquiry into primary housework responsibilities may not offer the granularity of time-based measurements, it provides a higher degree of accuracy by minimizing recall errors, especially considering that the periods under investigation were several months removed from the time of data collection (Hook 2017; Lyonette and Crompton 2015).

This method also affords greater consistency in the comparisons by adjusting for situational changes, like a lockdown, that could temporarily alter the volume of chores yet not significantly shift the primary responsibility. For example, in households where women traditionally performed the majority of chores and had lower earnings, this pattern would likely persist during the lockdown. This would hold true even if men took on additional tasks in response to heightened domestic needs, given that the economic status quo remained a significant factor in housework division. Utilizing this qualitative approach allows us to exclude inconsequential shifts and focus only on substantial changes in the primary housework roles, thus highlighting cases that merit deeper theoretical exploration.

Respondents were asked about their family’s experience with long-time quarantine during the 2020 Spring Festival. To identify qualified participants for this study—those whose households were under quarantine without any intervening work-related activities and who reported stable economic status—follow-up questions concerning the housework division were posed only to those who indicated that “All family members experienced extended quarantine without work” and that there were “No changes in employment status during the lockdown”.

A mixed-method approach, combining a survey and interviews, was adopted to ensure the inclusivity of diverse household arrangements. The survey used a broad conceptualization of family, categorizing members by gender. The central questions of the survey (see Appendix A Table A2) aimed to explore the gender-based division of general housework and specific tasks to identify shifts during the lockdown period. However, it is important to note that this qualitative approach may not fully capture instances where changes in responsibilities were equally distributed between genders (e.g., mutual increases or decreases in tasks). To mitigate reporting bias stemming from social desirability, the survey options designated either female or male family members as the primary contributors to household labor. All other arrangements, including those involving an equal division of tasks, were categorized under “Others” and were subject to text-based follow-up for further clarification (Geist and Cohen 2011; Kan 2008).

Follow-up interviews probed further to capture the patterns of change and perceived reasons for such changes. The interview guidelines included three open-ended questions regarding primary houseworkers and reasons for changes:

- Q1: Who was the primary houseworker of (four types) at the usual time/before the lockdown?

- Q2: Who was the primary houseworker of (four types) during the lockdown?

- Q3: (For differences between Q1 and Q2 responses). Why did your family make such a change?

This approach potentially broadened applicable cases from heterosexual couples to more diverse circumstances as long as different sexes lived together.

The generational relationship between the named houseworker and the respondent was coded. Divisions in both households were queried if the respondent’s household structure changed during the lockdown (e.g., reunion with parents). For respondents who lived alone or without an opposite-sex member during either examined period (before or during the lockdown), housework divisions in the bigger family (e.g., parents’ home) were compared to maximize case inclusion. This approach, however, led to the technical exclusion of households comprising same-sex couples from the analysis. Consequently, in some cases, the respondent was not a houseworker; still, they provided a lens through which to observe the division in their family.

5.2. Survey Distribution

Fieldwork commenced in May 2020 after all lockdowns were lifted in mainland China. Utilizing a Qualtrics questionnaire and online interviews, I gathered data from adult residents, primarily disseminated through paid services on WeChat and Weibo, with the aim of collecting 2000 survey responses and 100 qualified interviews from Chinese citizens 18 and older. Voluntary response sampling, a technique frequently employed in online surveys, served as the chosen sampling methodology.

Upon survey completion, participants could opt for an interview by adding me via a provided QR code linked to my WeChat account. Once added as a contact, I introduced myself as a researcher and inquired about their willingness and availability to partake in an interview. Participants were offered the choice of verbal or written communication methods facilitated by the WeChat platform. Of the 100 participants who partook in interviews, 78 elected to provide written responses. Intriguingly, those who opted for verbal communication generally were older.

The selection of the response format may be subject to social desirability bias, a psychological tendency wherein respondents manage impressions or adjust their self-representations to conform with socially accepted norms or attitudes (Bergen and Labonté 2019). Written responses, compared to verbal ones, could potentially introduce further bias, given that they permit more time for reflection and editing (Jackson and Messick 1958). Nonetheless, the study’s design serves as a countermeasure against such biases. Specifically, the study employs a comparative analysis of the allocation of household labor before and during periods of pandemic-induced lockdowns. This methodology effectively mitigated bias, evidenced by the consistency in the respondents’ reporting of household chore distribution across the time frames examined (Paulhus 2002). This consistency enables the study to accurately capture any transitions in household labor dynamics, which is the primary focus of this research.

It is worth noting that while 26 respondents added my account, they did not respond to subsequent interview inquiries. Additionally, five interviews were prematurely terminated and were therefore not included in the final count toward the study’s targeted goals. Each interviewee received a CNY 30 incentive upon completion, encouraging them to circulate the survey within their networks.

Of the 2030 questionnaire responses collected by November 2020, 105 were removed due to the lack of housework-related input, and 256 were disqualified due to missing information. A total of 100 interviews were conducted by August 2020 involving respondents who had experienced extended quarantine without the presence of working family members. However, four interview cases were later removed from the analysis: these were instances where respondents lived without any family members of the opposite sex. Additionally, one case was excluded where the respondent resided solely with a young child before and during the lockdown period. The exact response rate for the questionnaire is undetermined due to the digital nature and wide range of solicitation networks. The interview response rate was 15.8% when including non-responsive participants or 12.7% when not, which aligns with typical online interview response rates.

6. Sample Distribution and Data Analysis Methods

6.1. Sample Distribution

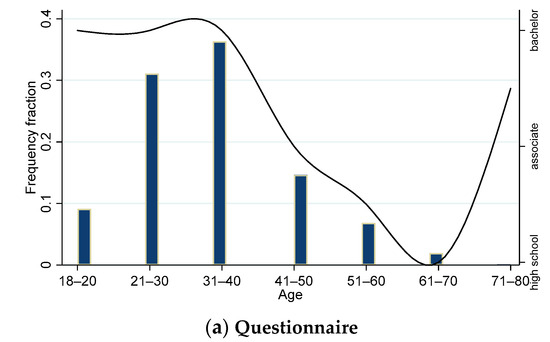

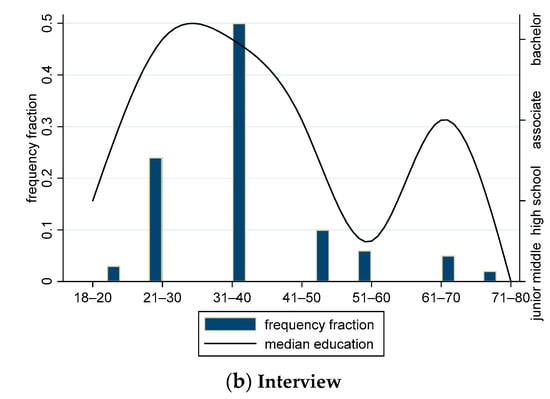

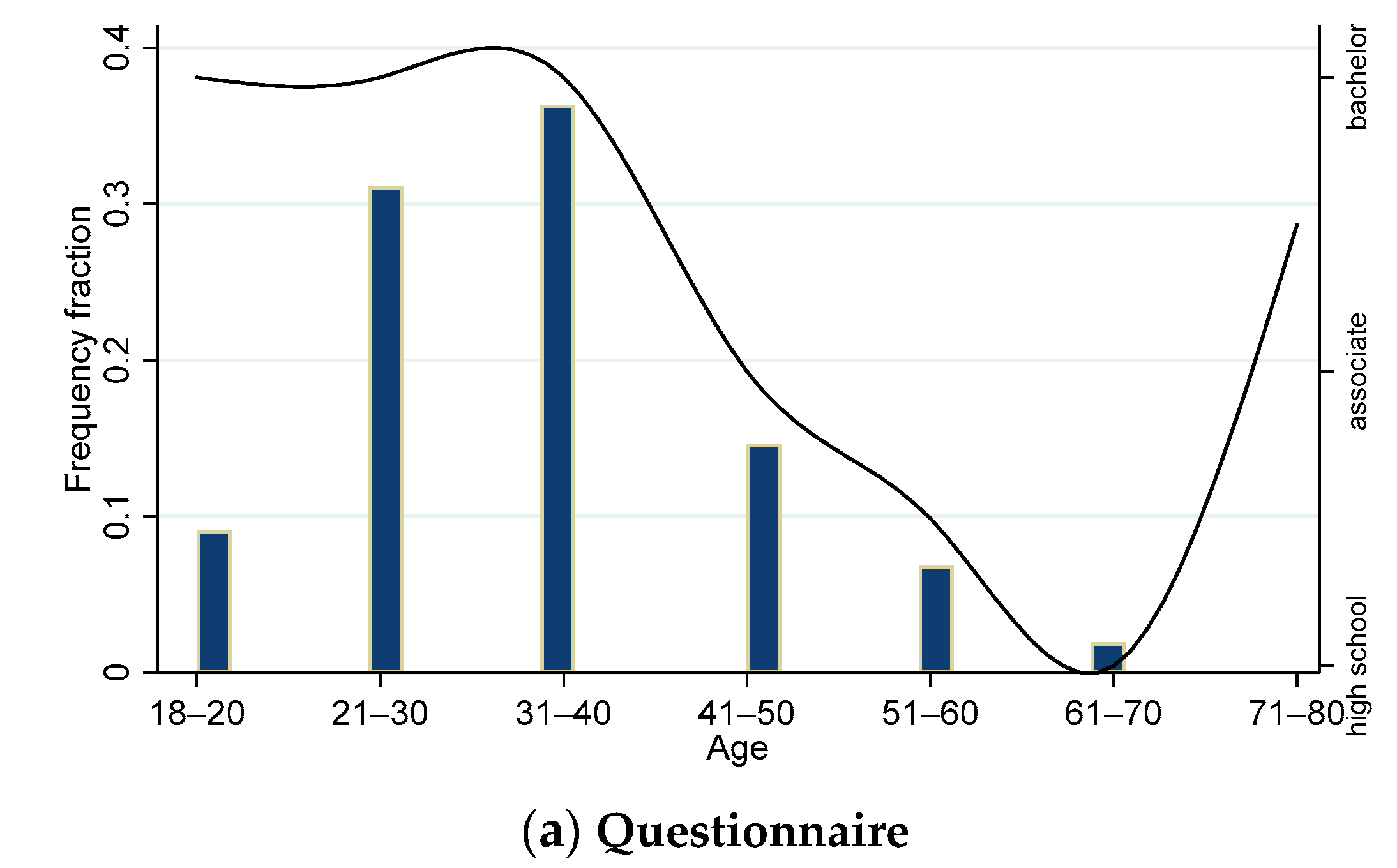

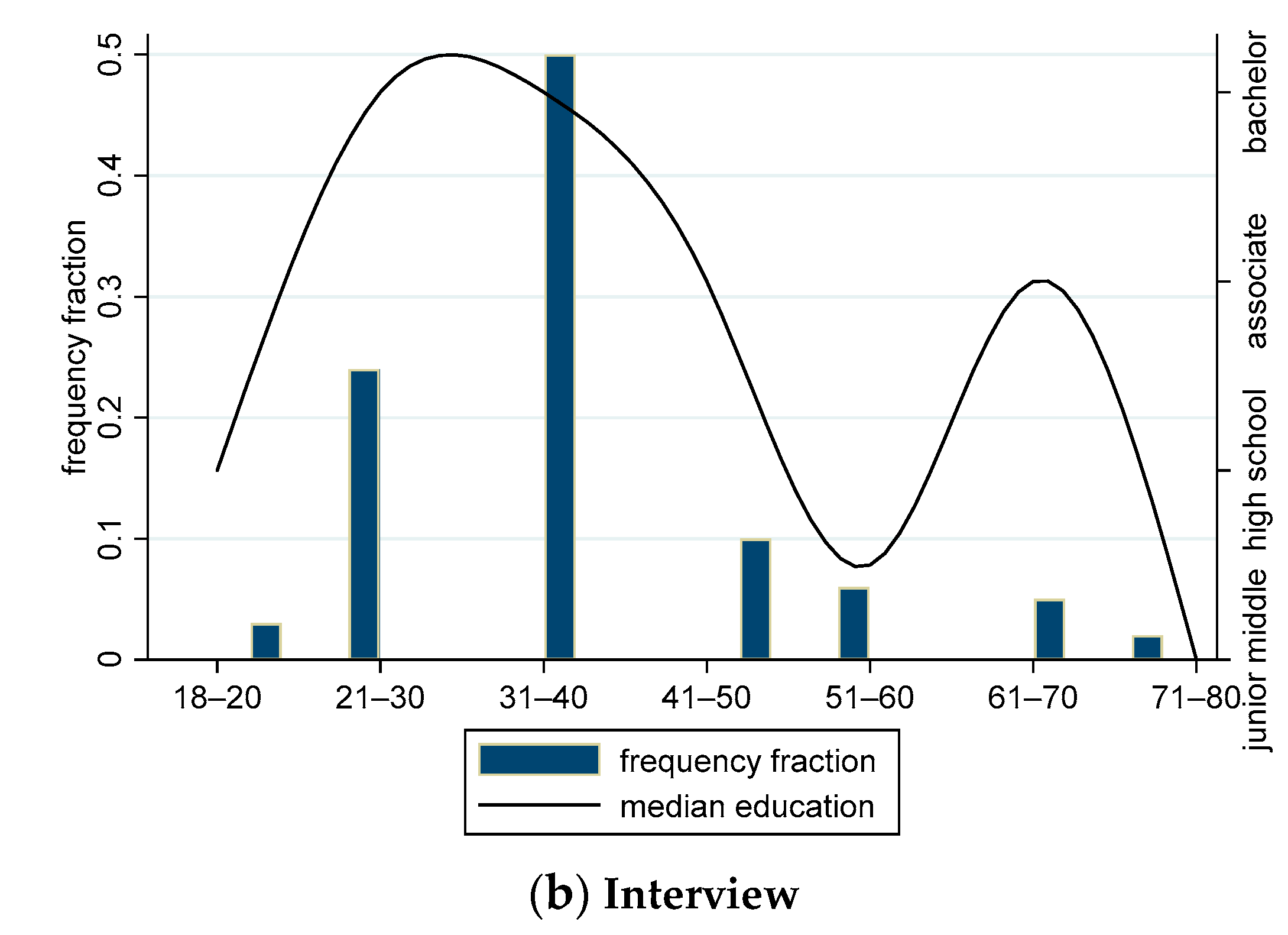

The interviewees technically form a subset of the survey participants per the recruitment design. A comparison of their distributions helps illustrate their representativeness. Out of 1669 survey responses, 57% (n = 950) were from females, over 70% were from urban dwellers, 62% had children, and nearly 61% held a bachelor’s degree or higher. Among the 100 interviewees, 78 were women, 90 lived in urban areas, 62 had children, and 61 possessed at least a bachelor’s degree. In contrast, China’s national urbanization rate in 2020 stood at 63.9%, with 37.2% of households having school-age children and around 15.6% of the population having a college degree (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2021). Additionally, the survey found a notable prevalence of intergenerational co-residence, with 60% of respondents living in multi-generational households before and 72% during the lockdown. This trend was similarly observed among the interviewees, with 52 living in such households before and 76 during the lockdown.

As Table 1 illustrates, the characteristics of respondents can significantly influence their reported reallocation of housework during the lockdown. For instance, an increase in household size was often associated with men contributing more to shopping, whereas women took on a greater overall load and cleaning tasks.

Table 1.

Gender-based reallocation of household labor during lockdowns: overall changes and detailed multivariate regression analysis (coded as 1 = from women to men or more equitable, 0 = unchanged, −1 = from men to women or less equitable).

The presence of young and school-age children often reinforces traditional gender roles. Women with such children are typically more involved in housework in addition to childcare than those without (Dunatchik et al. 2021; Hochschild and Machung 2012). As Table 1 demonstrates, the necessity for extra childcare or tutoring during the lockdown significantly impacts domestic labor distribution, with women showing increased involvement in cooking and cleaning. Lastly, higher education levels correlate with more egalitarian gender role attitudes (Steiber et al. 2016), linked to a more equitable distribution of household labor during lockdown periods (e.g., Berghammer 2022). This trend is corroborated in the current sample as well. As Table 1 indicates, education significantly predicts a more equal household labor distribution during lockdown across all task types except cooking, when controlling for other variables.

While the samples generally represent the population in terms of urban residence, there is an overrepresentation of females,2 families with children, and highly educated individuals. This skewness might arise from the survey’s content appealing more to females and parents and the internet-based method favoring technologically adept respondents, often seen in online and domestic activity surveys. Therefore, when interpreting the findings, it is crucial to remain cognizant of these potential biases, which could render the samples leaning toward being more egalitarian than might be observed in the broader population.

A comprehensive comparison and contrast between the survey and interview samples, demonstrating the representative nature of the interviewees’ sociodemographic distribution in relation to the larger survey sample, can be found in Appendix B.

6.2. Data Analysis Methods

I analyzed quantitative and qualitative data to validate patterns of change and the underlying reasons. Descriptive and statistical analyses were used for the quantitative data to reveal reallocation patterns, followed by qualitative data to show the perceived reasons for such changes.

I utilized ATLAS.ti software (version 9) to organize the interview data, codes, themes, and memos, including a reflexive diary. I used the template approach (Crabtree and Miller 1999) and the constant comparative method (Glaser and Strauss 1967) for analysis. First, I coded the interviews using a priori codes derived from the interview guidelines to sort data into two themes (who and why) based on task types. Then, I conducted inductive analysis within each category to identify common experiences and themes as subcodes. Using the subcodes as new deductive codes, I conducted a new cycle of inductive analysis to identify new patterns and themes with genders compared.

Comparisons were made between female and male family members of the same generation if their housework responsibilities (volume and type) changed during the lockdown. The comparisons were then drawn across generations, both between and within genders. This approach allowed for detecting housework reallocation trends, both intersexually and intergenerationally. The process was iterated until no new codes emerged. The last step was to detect the connections between the themes and distinguish the reasons for each identified change pattern. I grouped the codes by gender and generation according to their connections to each pattern. I conducted the coding process twice, with the second round two weeks after the first round to enhance dependability.

A total of 67 codes were deduced, revealing seven mutually exclusive patterns of housework reallocation during the lockdown period. These emergent patterns include (1) a shift of housework responsibilities from male to female members, (2) a shift from female to male members, (3) men taking on new household tasks, (4) women taking on new household tasks, (5) the redistribution of housework from male to other male members, (6) the redistribution from female to other female members, and (7) no change in the primary individual responsible for housework. The findings have been corroborated through the use of a reflexive diary log (Thorpe 2004). In the subsequent section, we will discuss themes and patterns that emerged as highly grounded and dense codes3 (Elliott 2018) to illustrate both the patterns and narrated reasons for the shifts in domestic responsibilities.

7. Result and Discussion

7.1. Theme 1: Who Did Housework?

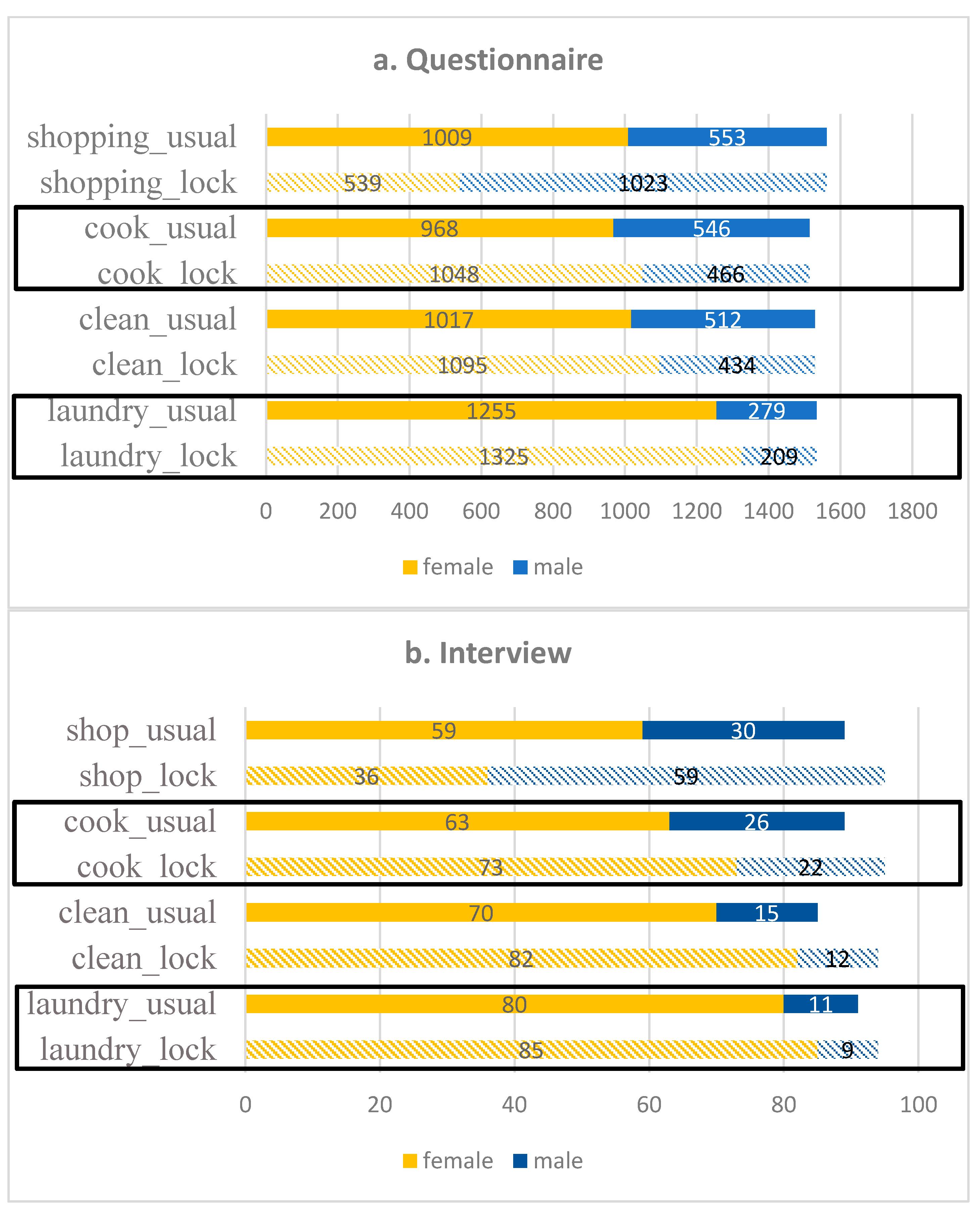

During lockdowns, most questionnaire respondents reported no change in household chore division, while 44% reported some changes (see Figure 2 and Table 2(I)). In over 65% of instances where changes were reported, male family members performed more housework, whereas female involvement increased in 31% of households. The proportion of responses indicating no change fell when it came to specific housework tasks, with 42% of questionnaire respondents and 22% of interviewees reporting no alteration in the four tasks under discussion.

Figure 2.

Changes in the primary houseworker by gender and task type.

Table 2.

Changes in housework division between genders during lockdowns.

The “Others” option—pertaining to cases where neither male nor female family members were the primary houseworkers—was chosen in 107 entries for shopping, 155 for cooking, 135 for laundry, and 140 for cleaning. For respondents who chose “Others” instead of a division between genders, a follow-up question was provided to clarify the specific situation. Among all text inputs, “paid house helpers did it” was the most commonly given detail when provided.

Interview cases that deviated from standard scenarios were meticulously coded. This coding accounted for instances where responsibilities were reported as equally distributed or collaboratively managed. These instances constitute a third category, supplementing the core categories that identify either males or females as the primary contributors to domestic tasks.

Consistency in change trends is evident when comparing the two samples: male family members reported taking on a greater portion of grocery shopping but less of other housework types. Such shifts are statistically significant, as the larger survey response sample corroborates.

Drawing upon in-depth interview data, the analysis reveals a key complexity: changes in household structure have notable effects on the division of domestic labor across the two periods examined. Specifically, households that changed their living arrangements during the lockdown displayed a more complicated dynamic. The shifts in the number of family members of different genders may have prompted adjustments in domestic labor allocation beyond simple redistribution among existing members.

To offer a clear portrayal of these effects, I have categorized the households based on the interview data. Generally, two distinct groups emerged concerning household structural changes: The first consists of families that downsized during the lockdown, accounting for five households; the second group comprises families that experienced reunions, totaling 24 households. Excluding these particular groups, the remaining 66 interviewees came from households that maintained a stable structure throughout the time frames under examination. Among these, 14 were not part of inter-generational co-residing households in either time frame.

In addition to these structure-based classifications, a separate subgroup emerged, consisting of families that had once employed domestic helpers. This subgroup introduced unique complexities in the division of domestic labor during the lockdown, primarily due to the loss of access to paid assistance, which could potentially influence the type and extent of family members’ domestic responsibilities.

Before the lockdown, household work was highly unequal, with females primarily responsible for most tasks. Men in these households were somewhat more involved in tasks like grocery shopping and cooking, but this was the case in only approximately one-third of the families surveyed. These findings align with existing research on the gender-based division of household labor in China under normal circumstances. For instance, a study conducted in Beijing revealed that women were responsible for the bulk of all surveyed household chores (Zuo and Bian 2001). Similarly, a cross-national comparative study indicated that 83% of Chinese women were in charge of meal preparation, 57% handled laundry, and 69% performed domestic cleaning on a daily basis. In stark contrast, fewer than 12% of Chinese men engaged in meal preparation or laundry, and a mere 17% contributed to daily household cleaning activities (Kan and Hertog 2017). Adding to this body of evidence, a recent study by Peng and Wu (2022), based on a national representative sample, disclosed that Chinese women spent, on average, 67% more time on household chores compared to their male counterparts. Intriguingly, the current sample—which skews toward a more educated demographic often presumed to espouse more egalitarian views on gender roles—did not markedly diverge from these well-established patterns in the actual allocation of household responsibilities, at least before the lockdown was implemented.

Nonetheless, a particular subsample is noteworthy: families that had employed domestic helpers showed a more balanced, and at times male-biased, division of household duties. In such households, the domestic helpers mainly took on cleaning, grocery shopping, and cooking tasks. As a result, aside from laundry, only a minor proportion of these families indicated that female members were principally responsible for the remaining household chores, as Table 3 details.

Table 3.

Percentage of female family members as primary houseworkers in household with (w) and without (w/o) paid helpers. A positive-value change rate indicates women’s increased responsibilities during lockdowns and vice versa.

During the lockdown, changes in domestic division varied across household tasks according to gender and generation. Overall, four distinct gender-specific patterns emerged concerning the increase in household labor. First, among the families that experienced changes, men substantially increased their grocery shopping participation during the lockdown, whereas women assumed greater responsibilities in cooking, cleaning, and laundry. Second, the transition to domestic insourcing disproportionately increased the domestic workload for women compared to men. Third, in multi-generational households—irrespective of any structural changes—there was a reported uptick in household chores performed by the younger generation during the lockdown. However, these generational shifts were also gender-specific: responsibilities for grocery shopping transitioned to younger men, while cooking, cleaning, and laundry duties were predominantly shifted to younger women. Finally, in households that experienced downsizing, the onus for all tasks invariably shifted to younger-generation women.

Male family members considerably increased their involvement in grocery shopping. In most cases (61% in the questionnaire sample and 62% in the interview sample), male family members were the primary shoppers, and about half of these men were not the primary shoppers before the pandemic. Even in households that relied primarily on online shopping during the lockdown (seven households), the majority (five households) reported that their male family members were responsible for picking up deliveries from outside (i.e., a designated area in the neighborhood), while women made the orders. In contrast, men’s participation in cooking, cleaning, and laundry decreased during the lockdowns.

Among families who transitioned to domestic insourcing due to the loss of paid helpers, the bulk of the additional housework predominantly fell upon women. As a result, the gender parity observed before the lockdown disintegrated. Women assumed a larger share of responsibilities in households that had previously employed domestic helpers compared to those that had not, as Table 3 evidences. Interestingly, the previously noted trend of men taking on more shopping duties did not persist in households that had once hired helpers. In these settings, women were primarily tasked with roles previously managed by domestic staff. This pattern may indicate the existing gender segregation commonly seen in the domestic help industry. Indeed, all interviewed households that had employed helpers—primarily for cleaning but sometimes for a range of tasks—reported their outsourced labor force to be female, except for non-routine, heavy-duty chores such as deep cleaning kitchen ventilation systems. This suggests that women reclaimed tasks that had been previously outsourced, highlighting the persistent gender disparity in domestic labor. Contrastingly, no gender segregation was observed in handling additional tasks that emerged due to circumstances such as the pandemic or lockdown. Both male and female family members were reportedly involved in these responsibilities.

These gender-based redistribution patterns in housework involve bidirectional shifts between men and women. Specifically, men have increasingly assumed shopping responsibilities previously held by women, while women have primarily taken over the other three tasks—cooking, cleaning, and laundry—from men. This reallocation is nuanced by intersectional variations in both gender and generational roles across different household chores, as Table 4 details.

Table 4.

Generational shifts in multi-generational households. Mean values for generations are reported, with the number of observations for each category. The generation of the respondent is denoted as 0; one or two generations older are indicated as 1 or 2, respectively, and one generation younger is indicated as −1.

In multi-generational households that retained stable structures during the lockdown, chores generally shifted toward younger men, particularly in the realm of shopping. Conversely, younger women took on a larger share of other household duties. When men were identified as the primary individuals responsible for cooking and cleaning—no cases were reported for laundry—they were more often from an older generation during the lockdown period than before. These shifts in both gender and generational roles are also present in households that experienced reunification during the lockdown. A notable difference here is that, while fewer in number, shopping tasks performed by female family members during the lockdown were primarily undertaken by women from the younger generation. Finally, among the few households that downsized during the pandemic, the reallocation of household chores was overwhelmingly skewed toward younger women across all categories of tasks.

7.2. Theme 2: Why Reallocated Housework?

When queried about the redistribution of housework during the pandemic, participants cited gender-specific reasons. These responses underscored the concept of ‘doing gender,’ where both female and male family members reinforced their gender roles through increased or decreased housework contributions in the changed circumstances.

Narrated reasons for men’s increased participation in housework included anxiety/fear, distance/mobility, physical strength, selective preferences, and low-quality demands. This increase was mainly seen during the early stages of lockdowns, where households in urban areas took advantage of quota-controlled leaving policies to go grocery shopping. Men’s increased involvement in grocery shopping and delivery picking was attributed to other family members’ anxiety and fear, particularly with health concerns articulated in the explanations (e.g., pregnant women, young children, or other health-related considerations). Additionally, men’s strength and mobility advantages were noted to explain their increased share when shopping was restricted to fewer trips or nearby markets were closed. For instance, F04 (18 yrs) remembered her father’s uncommon initiative to go grocery shopping during the pandemic to protect her and her mother, especially as her college entrance exam was approaching. F63 (33 yrs) attributed her husband’s delivery picking activities to cold weather and fear of the virus. F45 (28 yrs), a single woman living with her parents and younger sister during the lockdown, recalled her father as the primary shopper because “he drove and could carry more stuff.” M21 (31 yrs), reunited with his parents during the lockdown, shopped with his father instead of his mother, who was the primary shopper at the usual time. He explained their labor division: “[N]earby markets and stores were all closed. My dad drove to a supermarket farther away, and I was responsible for carrying stuff.”

Thus, the pandemic context may have temporarily altered the gender label associated with grocery shopping, allowing men to demonstrate bravery, responsibility, mobility, and strength, consistent with traditional masculine attributes. This temporary masculinization of the grocery shopping task resulted in an increase in men’s domestic participation, aligning with the concept of ‘doing gender.’ Similar results have been found in pandemic-related household research conducted in Italy, Britain, and America (Biroli et al. 2021).

In addition to being viewed as chivalrous or strong, other justifications made for men’s increased housework participation during the lockdowns paradoxically focused on men’s perceived inferiority in domestic chores, such as the lowered demand for quality or the occupation of female family members with more demanding domestic tasks, leaving men to handle the easier ones. For instance, F45 (28 yrs) noted, “Our [food] appetite was small then, so the shopping was relatively simple… It should not be stressful for him (her father) because we only needed a few kinds of stuff”.

Despite this increase in “easier” housework, it is still consistent with traditional masculinity. Similarly, women’s uptake of “tough” work aligns with the notion of femininity. This finding is consistent with Voßemer and Heyne’s (2019) study, which showed that both men and women spent more time on housework when staying home longer, but their division of labor was based on gender. From this perspective, the type of housework performed may be more important than the overall time spent on housework in displaying and affirming gender roles.

Narrated reasons for women’s increased participation in housework included the high quality, greater time availability, difficulty delegating or managing tasks, reduced household workload, and compensation for others’ domestic labor. These justifications were more nuanced and complex than those for men, likely due to the social perception of routine domestic activities as feminine and women’s involvement being taken for granted without the need for justification.

In contrast to men perceived as incompetent, female family members’ increased participation in domestic tasks was often justified by their superior skills and competence. For example, one prominent reason for women’s increased cooking contribution during the lockdown was the presence of picky eaters at home, especially for experienced female houseworkers whose skills and completion quality had been recognized.

The competence explanation was also applied to some female family members who took on new household responsibilities during the lockdown, even if they had not performed those before. For instance, F62 (34 yrs), an office clerk with rudimentary cooking skills before the pandemic, began contributing more actively to meal preparation by leveraging cooking apps for guidance. She eventually became the sole cook in her household as her culinary efforts were deemed superior to those of other family members. During the interview, F62 shared pictures of her cooking to demonstrate the quality and commented, “My daughter said they were better than restaurant food”.

The competence explanations for women’s increased participation in housework were not limited to cooking but were also present in other household tasks. Female family members were perceived to have more elaborate routines in doing specific tasks, resulting in perceived better quality and justifying their increased housework load when all were available. For example, respondents compared the laundry practices of female family members (e.g., completely handwashing, handwashing before machine washing, or separate laundry for underwear and outerwear) to those of men (e.g., single-load machine laundry) to exemplify women’s perceived superiority in completing housework. Implicit in these explanations is that women had more available time during the lockdown, which allowed them to take on more domestic responsibilities with perceived higher quality than they had been able to manage before when their market work or other activities had occupied their time.

Time availability was also explicitly acknowledged as a factor in explaining women’s increased household labor, especially for those young or middle-aged groups who were full-time employed before the lockdown. For example, F10 (33 yrs), a manager of a transnational company and a mother of a kindergartener, had previously faced challenges balancing work and family life, leaving her with limited time for household chores. However, when her child and parents—the primary houseworkers at the usual time—left the city for their hometown due to safety concerns, F10 found herself in an unusual situation with newfound time. With neither work nor child-rearing to consume her days, she took on the full spectrum of domestic chores.

On the other hand, the explanation of time availability was not explicitly used to justify men’s increased participation in household labor. On the contrary, the lack of time was often cited as a reason for men’s previous lack of involvement. F01 (38 yrs) described a conflict with her parents over the distribution of household chores when they all lived together in her parents’ house.

My parents did all the housework… Maybe that was too much, six people under a roof for a long time, they grumbled to me at my husband’s laziness and urged me to ask him to do some [housework]… My husband was very busy [in the usual time]—almost 200 days out of one year, either abroad or in the sky—so I didn’t ask him [to help with the housework] to give him a break. However, my parents saw no moves from him, [so] they were irritated and kept coming to me.

Similarly, M18 (29 yrs) provided insight into the lack of housework redistribution between his parents when they were both at home: “My father works at a forest reserve, so he’s rarely at home. When he does return, he prefers to rest and leaves all the housework to my mom.” The prior absence of men was often cited to excuse their limited housework contributions. Interestingly, having more time during the lockdown did not lead to an expansion of their duties, as their wives were also at home. Instead, their previous unavailability was used to rationalize their continued lack of involvement as a form of compensation. While having more time is necessary for increasing domestic contributions, it alone seems insufficient to expand men’s housework responsibilities. Even in the absence of economic activities during the lockdown, the influence of existing financial resources and power structures persisted in the division of household tasks, resulting in a lack of meaningful change.

Women’s increased participation was also attributed to the exhaustion from managing housework alongside family members who were passive or unwilling to offer help. When asked if male family members increased their household labor while at home, F66 (36 yrs) likened her husband to an “abacus bead” that did not move unless being moved.

F66: He hid in the study (and wouldn’t come out) unless you called him or came out only around mealtime.Q: So, did you increase your housework load at that time?F66: Yes, I was also at home, ain’t I?Q: Was there any agreement, or did you initiate taking housework? Why did you increase your undertakings?F66: No agreement. It’s like you had to call him, or he wouldn’t do (housework), so I was too lazy to call. I’d rather save the effort to do (the housework) myself.Q: So he was not very active (in doing housework)?F66: No. [He was behaving] like an abacus bead that only moves when you move it.Q: Do you also plan (household) tasks at the usual time? Does he do any?F66: Basically, yes. If you ask him, he will, but if you don’t ask, he won’t even bother looking at it.

If expanding the definition of housework to include organizational and cognitive tasks such as recognizing housework needs, coordinating schedules, planning meals, managing shopping lists and/or housekeepers, and monitoring finish quality, it becomes clear that female family members were heavily burdened with these responsibilities, as observed across the researched periods. This type of labor, though often invisible, underscores women’s critical role in organizing daily domestic life (Daminger 2019; Risman 2011). Zimmerman et al. (2002) coined the term “household quarterback” to describe this role, while men are often seen as providing support and only assisting women when the workload becomes overwhelming.

Female respondents reported taking on even more housework during the pandemic lockdown to alleviate the burden of organizational and cognitive labor. This finding suggests that such invisible labor can be energy-draining and resented (see also Daminger 2019). As a result, female houseworkers preferred hands-on tasks over organizational and cognitive labor when possible, and the lockdown practically increased their ability to complete housework independently by extending their time at home. This discovery confirms the notion of task specialization, with a specific mechanism from women’s perspective.

Alongside the challenge of delegating and managing housework with family members, the reduced demand for housework during the lockdown also contributed to women’s specialization in household tasks. M21 (31 yrs) reported fewer cleaning demands due to the absence of visiting relatives and friends. F74’s (35 yrs) family stopped tidying toys daily (coded as cleaning) when the children were at home, who would quickly mess the toys up again. F59 (61 yrs) reduced her laundry load by skipping all family members’ work attire during the job-free time. Consequently, housework sharing was reduced and often fully burdened by female family members.

Women’s increased participation in certain tasks during the lockdown was also driven by their perception of fairness or compensation for other family members’ increased housework labor. For instance, F77 (57 yrs) took over cleaning from her husband and explained that she was “let[ting] him take a rest for he already worked (for shopping)”. Similarly, M21’s (31 yrs) mother took care of the remaining housework after M21 and his father went shopping, including mopping the floor (coded as cleaning) and doing laundry that his father previously shared. In other words, primary houseworkers attempted to “balance” the load after other family members carried more than before.

These findings present a novel perspective on fairness and satisfaction in the housework division. Carriero’s (2011) distributive justice framework explains why women perceive fairness despite gendered and unequal housework division through two referents: inter-gender (e.g., a wife comparing her load to her husband’s) and intra-gender (e.g., a woman comparing herself to other women or her husband to other men) comparisons. However, this study shows that houseworkers perceived the new, more equal division as “unfair” by comparing their own workload before and during the lockdown, thus defending the previous “unequal equity” by taking on tasks from others. This perception of fairness based on self-comparison may result in resistance to changes in housework division, even when other factors (i.e., earnings, time) have changed, as previously noted in research (e.g., Gershuny et al. 2005; Greenstein 2000; Lyonette and Crompton 2015; Risman and Johnson-Sumerford 1998). The effect was most pronounced among older-generation women, usually the primary houseworkers and organizers, supporting the notion of ‘doing gender.’ Furthermore, women’s pivotal role in housework organization enabled them to control others’ assignments while safeguarding their domains, acting as “gatekeepers” of gendered housework.

Narrated reasons for increased participation across all genders concentrated on preference and family reunion but with distinct expressions. For instance, families mentioned leisure or outings solely as the rationale for taking on grocery shopping or delivery picking. After being confined at home—mostly in small apartments—for an extended period, some families highly desired the opportunity to go out.

Except for me, [my family] fell over each other with going out… At last, it turned out to be a competition of getting up early, [because] who could get up earlier would take the pass to leave.(F45, 28 yrs)

I am good at shopping. [So] I made the (online) orders, and he (the husband) was responsible for picking them up as couriers couldn’t get into our unit. He could grasp the chance to enjoy some cigarettes on the way.(F10, 33 yrs)

Even though this rationale was classified gender-neutral as it was identified in justifications for workload taken by all genders, it was more likely to be applied to male family members, perhaps because they were primarily responsible for shopping or delivery pickup during lockdowns.

Interest in cooking was a reason for increased participation among family members during the lockdown, observed in eight cases (six females and two males), who often received social rewards for their contribution. For example, F62 (34 yrs), who learned cooking from apps and was appreciated by her daughter, stated, “Just follow (the instructions given by) the apps. [It’s] very interesting and fulfilling after you finish them.” Since female family members predominantly performed cooking, the interest was skewed toward explaining women’s increased participation, particularly for those young or middle-aged who were previously unavailable for the activity before the lockdown.

Generational Differences in the redistribution of household chores emerged among multi-generational families during the lockdown period. These shifts occurred irrespective of whether families had recently reunited or lived together before the lockdown. Specifically, when the primary individual responsible for household chores was male, there was a shift in roles during family reunions: the younger generation primarily took over the task of grocery shopping, while the older generation assumed cooking and cleaning, albeit in very few cases (refer to Table 4 for details). Conversely, when the primary houseworker was female, the responsibility for all examined chores consistently shifted toward the younger generation.

The reasons cited for these changes are consistent with the aforementioned gender divisions. Emphasis was often placed on the physical strength, bravery, and health of younger male family members when grocery shopping was assigned during the pandemic. Conversely, the increased availability of younger female family members was frequently noted as the rationale for their assumption of other household chores.

Goldscheider and Lawton (1998) posit that living in a multi-generational household can reinforce traditional gender norms within the family structure. As observed, while most household chores are traditionally considered feminine, the role of grocery shopping has been masculinized in this particular context. This strengthening of conventional gender roles may have influenced younger family members to conform to these norms, resulting in women assuming a greater share of domestic responsibilities and men reducing their involvement in all tasks except grocery shopping. The more balanced participation of older generations, especially among male family members, aligns with the concept of de-gendering in later life stages (Silver 2003). This suggests that the expression of masculinity among older men is generally less emphasized compared to their younger counterparts, leading to unique intergenerational patterns in the distribution of household chores between genders.

The reallocation of housework during lockdowns revealed the manifestation of ‘doing gender’ in individual, interactive, and institutional contexts, affecting the use of increased time availability for housework. Increased time availability enabled women to take on more household responsibilities, but additional changes may be necessary to increase men’s participation. During China’s pandemic lockdown, the temporary masculinization of grocery shopping resulted in a dramatic increase in male housework participation, but only in shopping activities.

Women’s time availability enabled them to specialize in domestic tasks for their perceived better-quality household services or reduce the organizational and cognitive labor required for timely tasks. This underscores the gender-based division of household labor, where women serve as the main contributors. As the contributions from these main contributors grew due to either additional available time or a decrease in their domestic workload, the need for supplemental contributors, generally men, lessened. This led to a reduction in shared domestic responsibilities across all activities except for grocery shopping.

During the lockdown period, the increase in domestic labor performed by younger women was commonly attributed to their greater availability, owing to a reduction in external work commitments and other activities.

In multi-generational households, the distribution of household chores was significantly biased toward the younger generation. More precisely, younger men predominantly assumed the responsibility of grocery shopping, while younger women were chiefly tasked with other domestic duties. In this particular context, grocery shopping has taken on a masculine connotation, whereas other household tasks continue to be perceived as traditionally feminine. This accentuated division of labor underscores the concept of ‘doing gender’ among younger family members, particularly when cohabiting with older relatives.

When put into context, it becomes evident that the notion of ‘doing gender’ serves as a pivotal factor in shaping the allocation of household responsibilities for both men and women, even when men exhibit increased participation in certain chores.

In contrast to existing research, the current study provides a unique lens on this issue by focusing on the initial period of China’s stringent lockdown, which coincided with the Spring Festival—a time when employment status was largely stable while productive activities were on hold. This setting allowed us to exclude the effect of economic status as a variable influencing the division of household labor. Surprisingly, even when economic factors were controlled for, traditional gender patterns persisted.

The findings of this study challenge the commonly held belief that economic considerations play a significant role in dictating the gender-based division of household chores. In the absence of economic fluctuations and participation, the persistence of traditional domestic labor roles can more directly be attributed to ingrained gender norms. The lockdown, in this case, served as an unencumbered platform for the manifestation of these deeply rooted gender norms, free from the usual time constraints that might otherwise intervene.

8. Conclusions

The lockdowns in China during the COVID-19 pandemic offered a valuable opportunity to observe changes in household labor when all genders were homebound and job-free while employment status remained constant. This mixed-method study investigated patterns and reasons for housework reallocation in a unique context.

Housework sharing increased during the lockdown, but only men’s participation in grocery shopping increased significantly while other routine duties like cooking, cleaning, and laundry decreased. This gender-task pattern was mirrored in multi-generational households, where younger family members were more likely to assume these roles. Notably, when domestic tasks were insourced, the burden of housework increased more substantially for women than men.

Regarding reasons for reallocation, the study found that ‘doing gender’ had dominant effects through increased time availability and task specialization. Although necessary for increased housework participation, time availability alone was only sufficient to increase women’s household workload, particularly those who were full-time employed. Men’s participation required additional changes, such as masculinizing domestic tasks or female family members’ time constraints. The unique context of China’s pandemic lockdowns temporarily relabeled grocery shopping with traditional masculine attributes, increasing men’s participation alongside increased time availability. The perceived gender-based difference in household labor quality, the difficulty in delegating housework, and the reduced workload facilitated women’s task specialization and increased their participation while all genders were available. The notion of ‘doing gender’ played a pivotal role in shaping the gendered distribution of housework across generations.

This study corroborates that the housework reallocation during China’s stringent lockdowns mirrored trends observed in other nations, where changes in employment status were considered a significant factor in the gender-based division of housework. This affirmation strengthens the premise of the ‘doing gender’ thesis as a dominant factor in dictating the distribution of housework, irrespective of changes in time, economic parameters, or the lack thereof.

As a pioneering study exploring gender and generational housework reallocation during an urgent crisis, this research has various limitations. First, the workload information relies entirely on respondents’ retrospective reporting, inherently introducing recall biases and potential distortions due to reporting habits (Kan 2008). However, using a qualitative probing method, asking about the primary housework provider, may reduce such inaccuracies compared to strategies detailing hours spent on household activities. Still, this approach only captures significant changes, not the subtler adjustments that may be more prevalent, making the second shortcoming.

Additionally, the study’s samples are skewed toward female participants, which presents another concern. The insights drawn from interview narratives are likely biased, disproportionately reflecting women’s perspectives on domestic labor.

Next, this study consciously excludes childcare despite acknowledging its substantial influence on housework reallocation. While several instances demonstrate the intertwined decision-making process of childcare and housework divisions, I chose not to incorporate childcare due to its inherent complexity and potential to distract from the main focus of the study. Theoretically, decisions regarding childcare and housework may be underpinned by different dynamics, with housework often perceived as a more feminine and less enjoyable task (Sullivan 2013). Not all households in the current sample bore childcare responsibilities, yet all had housework tasks. Moreover, childcare requirements significantly shift with a child’s age and developmental stage, necessitating varying care providers. Despite these considerations, this paper does not encompass the full scope of domestic activities, which merits separate, in-depth exploration. A separate analysis focusing on childcare duties found that households with young children exhibited a less equitable division of housework, a disparity that was further exacerbated during the lockdown.

Another limitation lies in the varying durations of lockdowns and the dynamic nature of household divisions. As the lockdown extended, the division of household tasks may have shifted. Unfortunately, this study’s retrospective approach does not allow tracking of these potential fluctuations over time. A possible post hoc strategy could involve distinguishing between respondents residing in areas enduring extended lockdowns and those who did not. After applying this strategy and excluding respondents who reported living in Hubei province, Beijing, or Tianjin during the lockdown (refer to Table A1), the pattern of changes remained consistent, suggesting that the lockdown duration did not substantially influence the overall trends in the housework division, as measured by the role of primary houseworkers (detailed results available upon request).

Finally, as noted in the Sample Distribution section, the current samples are biased toward highly educated individuals, potentially inflating their representativeness of China’s broader population. Higher education levels are often associated with greater resource access and progressive gender ideologies. Although the division of housework in the samples was consistent with nationally representative data before the lockdown, this skew could still influence how housework was reallocated during the lockdown period. Consequently, it is important to recognize that this sample bias might portray a level of gender equality higher than the general population.

Funding

This research was funded by the Faculty First Award at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (20-0292).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author extends her sincere appreciation to Arielle Kuperberg for her instrumental role in conceptualizing the idea of this study. Special thanks are also due to Cindy Brooks Dollar for her invaluable and repeated input on various drafts of this paper. Gratitude is further extended to colleagues and graduate students in the Sociology Department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG), whose contributions during the working paper series were pivotal in refining the initial draft of this research. Additionally, the author is grateful to Jerry A. Jacobs for his insightful enhancements that significantly enriched this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Duration of Tier-1 lockdowns responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in mainland China.

Table A1.

Duration of Tier-1 lockdowns responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in mainland China.

| Code | Provincial Unit | Close Date * | Reopen Date * | Lockdown Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beijing | 23 January 2020 | 30 April 2020 | 98 |

| 2 | Chongqing | 24 January 2020 | 1 March 2020 | 47 |

| 3 | Shanghai | 24 January 2020 | 24 March 2020 | 60 |

| 4 | Tianjin | 24 January 2020 | 30 April 2020 | 97 |

| 5 | Anhui | 27 January 2020 | 25 February 2020 | 32 |

| 6 | Fujian | 24 January 2020 | 27 February 2020 | 34 |

| 7 | Guangdong | 23 January 2020 | 24 February 2020 | 32 |

| 8 | Gansu | 25 January 2020 | 21 February 2020 | 27 |

| 9 | Guangxi | 24 January 2020 | 24 February 2020 | 31 |

| 10 | Guizhou | 24 January 2020 | 24 February 2020 | 31 |

| 11 | Henan | 25 January 2020 | 19 March 2020 | 54 |

| 12 | Hubei | 24 January 2020 | 2 May 2020 | 99 |

| 13 | Hebei | 24 January 2020 | 3 April 2020 | 70 |

| 14 | Hainan | 25 January 2020 | 26 February 2020 | 32 |

| 15 | Heilongjiang | 25 January 2020 | 5 March 2020 | 40 |

| 16 | Hunan | 24 January 2020 | 11 March 2020 | 47 |

| 17 | Jilin | 25 January 2020 | 26 February 2020 | 32 |

| 18 | Jiangsu | 25 January 2020 | 24 February 2020 | 30 |

| 19 | Jiangxi | 24 January 2020 | 12 March 2020 | 48 |

| 20 | Liaoning | 25 January 2020 | 22 February 2020 | 28 |

| 21 | Inner Mongolia | 25 January 2020 | 25 February 2020 | 31 |

| 22 | Ningxia | 25 January 2020 | 28 February 2020 | 34 |

| 23 | Qinghai | 26 January 2020 | 26 February 2020 | 31 |

| 24 | Sichuan | 24 January 2020 | 26 February 2020 | 33 |

| 25 | Shandong | 24 January 2020 | 8 March 2020 | 44 |

| 26 | Shaanxi | 25 January 2020 | 28 February 2020 | 34 |

| 27 | Shanxi | 25 January 2020 | 23 February 2020 | 29 |

| 28 | Xinjiang | 25 January 2020 | 26 February 2020 | 32 |

| 29 | Tibet | 30 January 2020 | 7 March 2020 | 37 |

| 30 | Yunnan | 24 January 2020 | 24 February 2020 | 31 |

| 31 | Zhejiang | 23 January 2020 | 1 March 2020 | 38 |

* Information was gathered by monitoring and tracking the announcements made by each provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The table presented has been adapted and modified from the working paper titled “Pandemic Lockdowns and Trust in Local Government in China” by Ting Wang, Bing Ye, and Yucong Zhao.

Table A2.

Core questions in questionnaire.

Table A2.

Core questions in questionnaire.

| Question | Choices (Single) | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall change in the housework division | During the COVID-19 lockdowns in early 2020, was the housework division more equal between genders? |

|

| (If the answer to the preceding question is either option a or b) The housework division was more/less equal during the lockdowns because |

| |

| Activity-specific change | Before the lockdown, who did most cooking/cleaning/shopping/laundry? |

|

| During the lockdown, who did most cooking/cleaning/shopping/laundry? |

|

Appendix B. Survey and Interview Sample Comparison