Primary Amenorrhea in Adolescents: Approach to Diagnosis and Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- A properly functioning hypothalamus–pituitary axis;

- -

- Well-developed and active ovaries;

- -

- Outflow tract without abnormalities.

2. Definition

- -

- Adolescent who did not reach menarche by the age of 14 years;

- -

- Adolescent who did not reach menarche after more than 3 years since thelarche occurrence;

- -

- Adolescent who did not reach menarche by the age of 13 years and without secondary sexual characteristic development;

- -

- Adolescent who did not reach menarche by the age 14 years and with suspected eating disorder or excessive exercise, with signs of hyperandrogenism, or with failure to thrive.

3. Causes of Primary Amenorrhea

- 1—Endocrine defects of the hypothalamus–pituitary–ovarian axis.

- 2—Genetic defects of the ovary.

- 3—Metabolic diseases.

- 4—Autoimmune diseases.

- 5—Infections.

- 6—Iatrogenic causes (radiotherapy, chemotherapy).

- 7—Müllerian tract defects.

- 8—Environmental factors.

- 9—Idiopathic

| 1—Endocrine Defects within the Hypothalamo–Pituitary–Ovarian Axis (HPOa) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2—Müllerian defects (Normogonadotropic amenorrhea) |

3.1. Endocrine Defects of the Hypothalamus–Pituitary–Ovarian Axis

3.1.1. Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism

Congenital Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism

- -

- The genes encoding kisspeptin and its receptor (KISS1 and KISS1R) and neurokinin B and its receptor (TAC3 and TACR3), which regulate GnRH release, should be the first to be screened in clinical settings for equivocal cases, such as delayed puberty versus idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, because they are the main causes of GnRH pulse generator defects.

- -

- In Kallmann syndrome, the screening of specific genes should be prioritized based on their association with clinical features: synkinesis (KAL1), dental agenesis (FGF8/FGFR1), bone anomalies (FGF8/FGFR1), and hearing loss (CHD7, SOX1). New genes have been recently identified and the list of genes involved in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism is still growing.

Acquired Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism

- -

- Brain tumors: craniopharyngioma, astrocytoma;

- -

- Central nervous system infiltration diseases (e.g., histiocytosis);

- -

- Chemo- or radiotherapy;

- -

- Hyperprolactinemia [11].

Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea

3.1.2. Hypergonadotropic Hypogonadism

- -

- XX hypergonadotropic hypogonadism;

- -

- X0 hypergonadotropic hypogonadism;

- -

- XY hypergonadotropic hypogonadism.

XX Hypergonadotropic Hypogonadism

- (a)

- Premature ovarian insufficiency

- (b)

- Metabolic disorders

- Classic galactosemia affects around 1/25,000 of new-born girls and is due to mutations in the GALT gene that decrease/abolish galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltranserase activity, leading to the toxic accumulation of galactose in the ovaries and in the whole body. Several mechanisms have been postulated, including the direct toxicity of galactose to oocytes and follicles, leading to accelerated atresia of the ovarian pool [17].

- Thalassemia and sickle cell disease are the most prevalent inherited hemoglobin disorders (recessive pattern). Transfusion-related iron overload may lead to gonad dysfunction, the absence of puberty development, and PA [18].

- Other metabolic disorders also may be associated with PA [19], such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (due to 17-hydroxylase enzyme deficiency) and aromatase deficiency. In some girls, PA may be associated with type 1 diabetes, low BMI and abnormal pulsatile GnRH secretion.

- Obesity: adolescents with severe obesity usually have elevated levels of plasma androgens. The normalization of plasma androgens upon weight loss leads to the resumption of ovulation, suggesting that overweight-related hyperandrogenism is the cause of amenorrhea in adolescent girls with obesity [20].

- PCOS: It is not rare that PA may lead to the detection of PCOS, especially when severe insulin resistance is present in the peri-pubertal period in adolescents with central obesity, early hyperinsulinism and insulin resistance [21,22]. Many PCOS features appear during early adolescence, such as oligomenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, and signs of hyperandrogenism. PA is an uncommon manifestation of PCOS (1.4 to 14% of girls present PA as an initial feature of PCOS) [21]. Early hyperinsulinism, insulin resistance, and central obesity are observed in girls with severe PCOS [22].

- (c)

- Autoimmune diseases

- (d)

- Infections

- (e)

- Iatrogenic causes (radiotherapy, chemotherapy)

- (f)

- Environmental factors (lifestyle, EDCs)

- (g)

- Idiopathic

X0 Hypergonadotropic Hypogonadism: Turner Syndrome

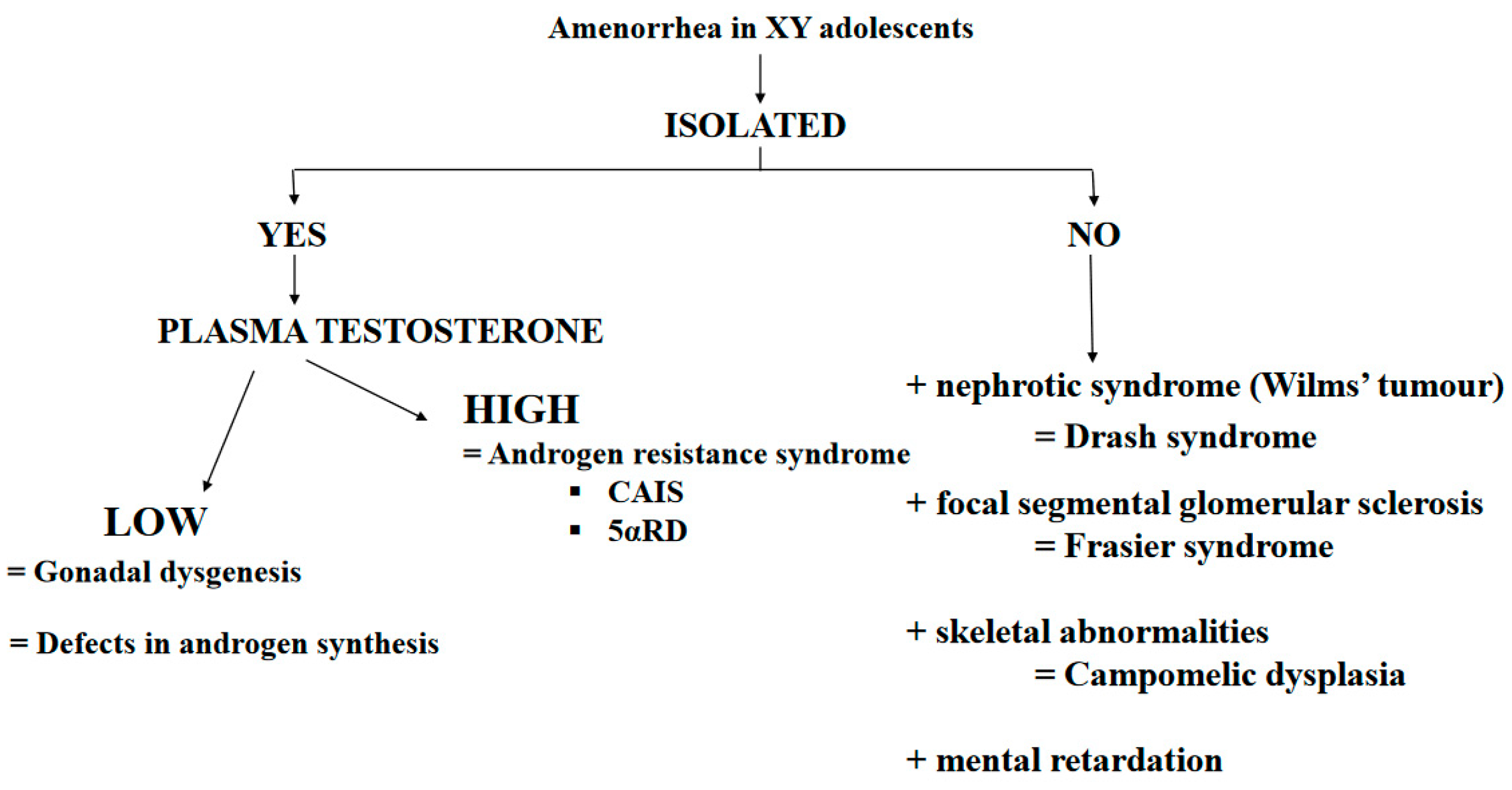

XY Hypergonadotropic Hypogonadism: Disorders of Sex Development (DSD)

- (a)

- Gonad dysgenesis:

- (b)

- Testosterone Production Defects

- (c)

- Androgen-resistance disorders

- Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS)

- 5α-reductase deficiency

3.2. Normogonadotropin Ovulatory Amenorrhea: Congenital Müllerian Defects

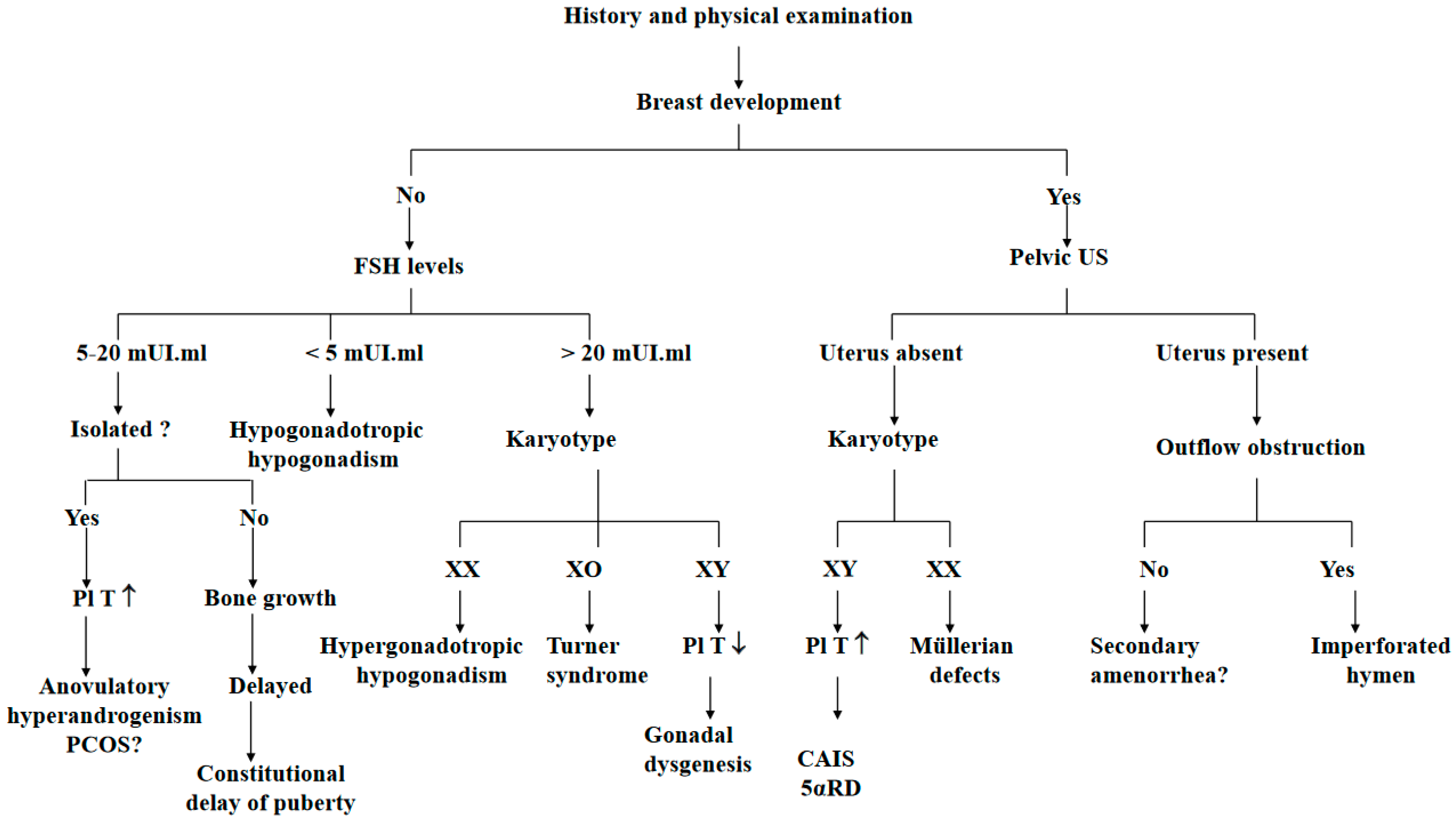

4. Primary Amenorrhea Evaluation

- (a)

- PA evaluation begins by collecting the patient’s medical history (general health and lifestyles), particularly to identify chronic diseases and exposure to radiation or chemotherapy during infancy. It is important to obtain information about the history of galactorrhea, headache, and cyclical abdominal pain.

- (b)

- A physical examination must include height and weight, and a body mass index (BMI) calculation. The Tanner stage of breast development is a good marker of the degree of estrogenization [19]. Features suggestive of Turner syndrome must be recorded. A scrupulous examination of the external genitalia and cervix should be conducted [5].

- (c)

- Imaging studies routinely include pelvic ultrasonography to confirm the presence of ovaries and the uterus.

- (d)

- The initial hormone evaluation is limited to the serum-follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), testosterone and prolactin [10]. Pregnancy must be ruled out because adolescents may ovulate before the first period. A karyotype should be obtained in all adolescents with high FSH serum levels.

- In function of the initial examination: PA with or without breast development, with or without evidence of androgen excess, with or without galactorrhea, with or without weight loss, with or without growth failure.

- In function of the FSH levels: hypergonadotropic hypogonadism (elevated FSH), hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (low FSH) or eugonadism (normal FSH).

- In function of the karyotype: XX, XO or XY [51].

5. Management

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klein, D.A.; Paradise, S.L.; Reeder, R.M. Amenorrhea: A Systematic Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 100, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, C.; Gaspari, L.; Maimoun, L.; Kalfa, N.; Paris, F. Disorders of puberty. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 48, 62–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, N.H.; Carlson, J.L. The Pathophysiology of Amenorrhea in the Adolescent. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1135, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmreck, L.S.; Reindollar, R.H. Contemporary issues in primary amenorrhea. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2003, 30, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Master-Hunter, T.; Heiman, D.L. Amenorrhea: Evaluation and treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2006, 73, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Popat, V.B.; Prodanov, T.; Calis, K.A.; Nelson, L.M. The Menstrual Cycle: A biological marker of general health in adolescents. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1135, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Pediatrics; Committee on Adolescence; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Menstruation in Girls and Adolescents: Using the Menstrual Cycle as a Vital Sign. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 2245–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.M.; Nelson, L.M. Amenorrhea and bone health in adolescents and young women. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 15, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoncini, T.; Genazzani, A.R.; Giannini, A. The Long-Term Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Amenorrhea. In Frontiers in Gynecological Endocrinology; Sultan, C., Genazzani, A., Eds.; ISGE Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Current evaluation of amenorrhea. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 90, S219–S225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, P.; Nachtigall, L.B. Hyperprolactinemia and Pituitary Causes of Amenorrhea. In Amenorrhea; Santoro, N., Neal-Perry, G., Eds.; Contemporary Endocrinology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pedreira, C.C.; Maya, J.; Misra, M. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: Impact on bone and neuropsychiatric outcomes. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 953180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Berga, S.L.; Kaplan, J.R.; Mastorakos, G.; Misra, M.; Murad, M.H.; Santoro, N.F.; Warren, M.P. Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 1413–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanner, L.; Hakim, J.C.; Kankanamge, C.D.; Patel, V.; Yu, V.; Podany, E.; Gomez-Lobo, V. Noncytotoxic-Related Primary Ovarian Insufficiency in Adolescents: Multicenter Case Series and Review. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2018, 31, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskenazi, S.; Bachelot, A.; Hugon-Rodin, J.; Plu-Bureau, G.; Gompel, A.; Catteau-Jonard, S.; Molina-Gomes, D.; Dewailly, D.; Dodé, C.; Christin-Maitre, S.; et al. Next Generation Sequencing Should Be Proposed to Every Woman with “Idiopathic” Primary Ovarian Insufficiency. J. Endocr. Soc. 2021, 5, bvab032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Roy, S.; Halder, A. Study of frequency and types of chromosomal abnormalities in phenotypically female patients with amenorrhea in Eastern Indian population. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Erven, B.; Berry, G.T.; Cassiman, D.; Connolly, G.; Forga, M.; Gautschi, M.; Gubbels, C.S.; Hollak, C.E.; Janssen, M.C.; Knerr, I.; et al. Fertility in adult women with classic galactosemia and primary ovarian insufficiency. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamsen, L.S.; Kristensen, S.G.; Pors, S.E.; Bøtkjær, J.A.; Ernst, E.; Macklon, K.T.; Gook, D.; Kumar, A.; Kalra, B.; Andersen, C.Y. Consequences of β-Thalassemia or Sickle Cell Disease for Ovarian Follicle Number and Morphology in Girls Who Had Ovarian Tissue Cryopreserved. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 11, 593718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.Y.; Cheon, C.K. Evaluation and management of amenorrhea related to congenital sex hormonal disorders. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 24, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itriyeva, K. The effects of obesity on the menstrual cycle. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2022, 52, 101241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmiel, M.; Kives, S.; Atenafu, E.; Hamilton, J. Primary Amenorrhea as a Manifestation of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome in Adolescents: A unique subgroup? Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2008, 162, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledger, W.L.; Skull, J. Amenorrhoea: Investigation and treatment. Curr. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2004, 14, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeliga, A.; Calik-Ksepka, A.; Maciejewska-Jeske, M.; Grymowicz, M.; Smolarczyk, K.; Kostrzak, A.; Smolarczyk, R.; Rudnicka, E.; Meczekalski, B. Autoimmune Diseases in Patients with Premature Ovarian Insufficiency—Our Current State of Knowledge. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowska, B. Autoimmune premature ovarian failure. Menopause Rev. 2016, 15, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, E.M.; Albert, A.; Murray, M.C. HIV and amenorrhea: A meta-analysis. AIDS 2019, 33, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cejtin, H.E.; Evans, C.T.; Greenblatt, R.; Minkoff, H.; Weber, K.M.; Wright, R.; Colie, C.; Golub, E.; Massad, L.S. Prolonged Amenorrhea and Resumption of Menses in Women with HIV. J. Women’s Health 2018, 27, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kooi, A.-L.L.F.; Mulder, R.L.; Hudson, M.M.; Kremer, L.C.; Skinner, R.; Constine, L.S.; van Dorp, W.; Broeder, E.V.D.-D.; Falck-Winther, J.; Wallace, W.H.; et al. Counseling and surveillance of obstetrical risks for female childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors: Recommendations from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 224, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneventi, F.; Locatelli, E.; Giorgiani, G.; Zecca, M.; Locatelli, F.; Cavagnoli, C.; Simonetta, M.; Bariselli, S.; Negri, B.; Spinillo, A. Gonadal and uterine function in female survivors treated by chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/or bone marrow transplantation for childhood malignant and non-malignant diseases. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 121, 856–865; discussion 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonska, O.; Shi, Z.; Valdez, K.E.; Ting, A.Y.; Petroff, B.K. Temporal and anatomical sensitivities to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin leading to premature acyclicity with age in rats. Int. J. Androl. 2010, 33, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemaitilly, W.; Li, Z.; Krasin, M.J.; Brooke, R.J.; Wilson, C.L.; Green, D.M.; Klosky, J.L.; Barnes, N.; Clark, K.L.; Farr, J.B.; et al. Premature Ovarian Insufficiency in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 2242–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargus, E.; Deans, R.; Anazodo, A.; Woodruff, T.K. Management of Primary Ovarian Insufficiency Symptoms in Survivors of Childhood and Adolescent Cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2018, 16, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, S.L.; Laven, J.; Hakvoort-Cammel, F.; Schipper, I.; Visser, J.; Themmen, A.; de Jong, F.; Heuvel-Eibrink, M.v.D. Assessment of ovarian reserve in adult childhood cancer survivors using anti-Mullerian hormone. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 24, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Q.H.Y.; Anderson, R.A. The role of antimullerian hormone in assessing ovarian damage from chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2018, 25, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-A.; Choi, J.; Park, C.S.; Seong, M.-K.; Hong, S.-E.; Kim, J.-S.; Park, I.-C.; Lee, J.K.; Noh, W.C.; ASTRRA Trial Investigators. Post-chemotherapy serum anti-Müllerian hormone level predicts ovarian function recovery. Endocr. Connect. 2018, 7, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reifschneider, K.; Auble, B.A.; Rose, S.R. Update of Endocrine Dysfunction following Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 1536–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Zhou, C.; Rattan, S.; Flaws, J.A. Effects of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals on the Ovary. Biol. Reprod. 2015, 93, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vabre, P.; Gatimel, N.; Moreau, J.; Gayrard, V.; Picard-Hagen, N.; Parinaud, J.; Léandri, R. Environmental pollutants, a possible etiology for premature ovarian insufficiency: A narrative review of animal and human data. Environ. Health 2017, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigante, E.; Picciocchi, E.; Valenzano, A.; Dell’Orco, S. The effects of the endocrine disruptors and of the halogens on the female reproductive system and on epigenetics: A brief review. Acta Medica Mediterr. 2018, 34, 1295. [Google Scholar]

- Hoag, B.D.; Tsai, S.L.; Williams, D.D.; Cernich, J.T. International Guideline Adherence in Girls with Turner Syndrome: Multiple Subspecialty Clinics versus Coordinated Multidisciplinary Clinic. Endocr. Pract. 2022, 28, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trolle, C.; Mortensen, K.; Hjerrild, B.E.; Cleemann, L.; Gravholt, C.H. Clinical care of adult Turner syndrome—New aspects. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Rev. 2012, 9 (Suppl. 2), 739–749. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, A.; Johannsen, T.H.; Stochholm, K.; Viuff, M.H.; Fedder, J.; Main, K.M.; Gravholt, C.H. Incidence, Prevalence, Diagnostic Delay, and Clinical Presentation of Female 46,XY Disorders of Sex Development. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 4532–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.F.; Filho, L.G.F.; Silva, K.I.; Trauzcinsky, P.A.; Reuter, C.; Souza, M.B.M. The XY female and SWYER syndrome. Urol. Case Rep. 2019, 26, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, C.; Lumbroso, S.; Paris, F.; Jeandel, C.; Terouanne, B.; Belon, C.; Audran, F.; Poujol, N.; Georget, V.; Gobinet, J.; et al. Disorders of Androgen Action. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2002, 20, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimoun, L.; Philibert, P.; Cammas, B.; Audran, F.; Bouchard, P.; Fenichel, P.; Cartigny, M.; Pienkowski, C.; Polak, M.; Skordis, N.; et al. Phenotypical, Biological, and Molecular Heterogeneity of 5α-Reductase Deficiency: An Extensive International Experience of 55 Patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimoun, L.; Philibert, P.; Bouchard, P.; Öcal, G.; Leheup, B.; Fenichel, P.; Servant, N.; Paris, F.; Sultan, C. Primary amenorrhea in four adolescents revealed 5α-reductase deficiency confirmed by molecular analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95(804.e1–804.e5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deligeoroglou, E.; Athanasopoulos, N.; Tsimaris, P.; Dimopoulos, K.D.; Vrachnis, N.; Creatsas, G. Evaluation and management of adolescent amenorrhea. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1205, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, I.d.M.P.e.; Britto, R.L. Diagnosis and treatment of müllerian malformations. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 59, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapczuk, K.; Kędzia, W. Primary Amenorrhea Due to Anatomical Abnormalities of the Reproductive Tract: Molecular Insight. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, C.; Biason-Lauber, A.; Philibert, P. Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster–Hauser syndrome: Recent clinical and genetic findings. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2009, 25, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newbery, G.; Neelakantan, M.; Cabral, M.D.; Omar, H. Amenorrhea in adolescents: A narrative review. Pediatr. Med. 2019, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, C.; Park, Y.; Pyun, J.-A.; Kwack, K. Next generation sequencing identifies abnormal Y chromosome and candidate causal variants in premature ovarian failure patients. Genomics 2016, 108, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasner, A.; Rehman, A. Primary Amenorrhea; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Seppä, S.; Kuiri-Hänninen, T.; Holopainen, E.; Voutilainen, R. Management of endocrine disease: Diagnosis and management of primary amenorrhea and female delayed puberty. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 184, R225–R242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldewey, S.K.L. Different approaches to Hormone Replacement Therapy in women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Gynecol. Reprod. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 2, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Huhtaniemi, I.; Hovatta, O.; La Marca, A.; Livera, G.; Monniaux, D.; Persani, L.; Heddar, A.; Jarzabek, K.; Laisk-Podar, T.; Salumets, A.; et al. Advances in the Molecular Pathophysiology, Genetics, and Treatment of Primary Ovarian Insufficiency. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 29, 400–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, E.J.; Im, D.H.; Park, Y.H.; Byun, J.M.; Kim, Y.N.; Jeong, D.H.; Sung, M.S.; Kim, K.T.; An, H.J.; Jung, S.J.; et al. Female with 46, XY karyotype. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2017, 60, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaspari, L.; Paris, F.; Kalfa, N.; Sultan, C. Primary Amenorrhea in Adolescents: Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Endocrines 2023, 4, 536-547. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines4030038

Gaspari L, Paris F, Kalfa N, Sultan C. Primary Amenorrhea in Adolescents: Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Endocrines. 2023; 4(3):536-547. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines4030038

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaspari, Laura, Françoise Paris, Nicolas Kalfa, and Charles Sultan. 2023. "Primary Amenorrhea in Adolescents: Approach to Diagnosis and Management" Endocrines 4, no. 3: 536-547. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines4030038

APA StyleGaspari, L., Paris, F., Kalfa, N., & Sultan, C. (2023). Primary Amenorrhea in Adolescents: Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Endocrines, 4(3), 536-547. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines4030038