PNAE (National School Feeding Program) and Its Events of Expansive Learnings at Municipal Level

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Context of PNAE at National Level

3. Cultural–Historical Activity Theory and Theory of Expansive Learning

4. Methodology and Methodological Procedures

5. Results

5.1. Activity System in the Municipality of Porto Velho

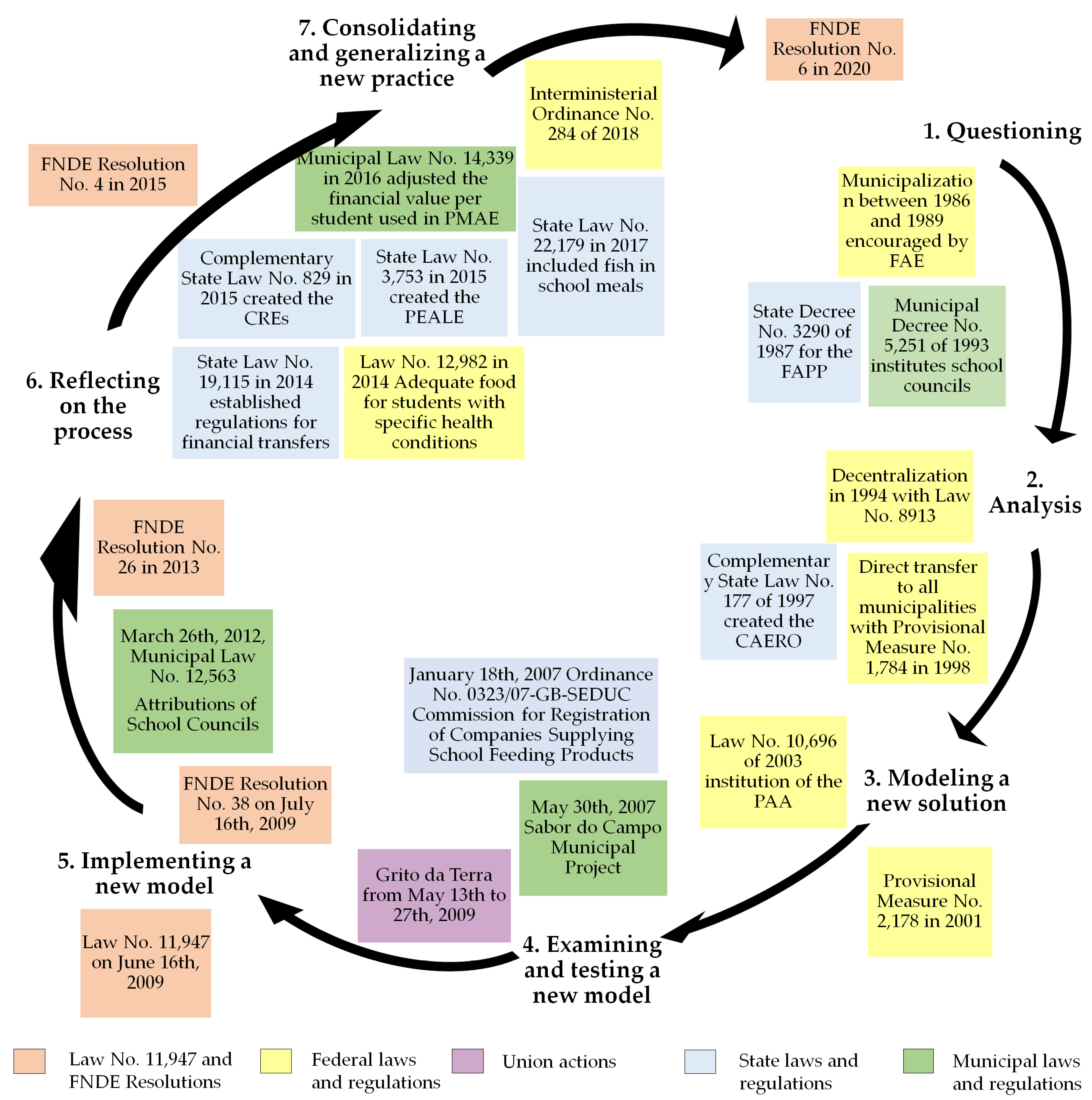

5.2. Expansive Learning to Comply with Law No. 11,947

5.2.1. Historical Facts between 1981 and 2002

5.2.2. Organization and Institution of Law No. 11,947 between 2003 and 2012

“It’s not from 2003, it’s from 1995 of Fernando Henrique Cardoso government... When it was 2003 we revived this. The first PAA was made here in Porto Velho. The first PAA when it was shelved in 95 during the Fernando Henrique Cardoso government... when Lula arrived, he rescued it there, but it was kind of stuck in the drawer who discovered this was Roberto Sobrinho there in Brasília. He wasn’t a candidate for anything at the time. He found out and came and called me, “there’s a law like that... does it interest us here in the city? I said “I’m interested” “How are we going to do it?” “I’m going to call the association”. 38 associations came, from these 38 associations we selected some that had document... we selected 8, of these 8, just 5 were approved. Of these 5 we did the project for Brasília, the PAA resource it was from Ministry of Social Development (MDS). When we started the PAA, to spread the PAA in Brazil, we took the project to Brasília. I went to show Lula, our first resource in Porto Velho, was of 622 thousand Reais. It was very sudden, we had to finish by 25 December … a SEMED server helped a lot.” ____Interviewee ECON01

“At the time of the Ministry of Citizenship, I took a basic technician’s course in Manaus, Santa Maria, in Rio Grande do Sul, Brasília, at family farming fairs. They sent me to Brasília, I know it was because I was one of the pioneers to participate in the MDA courses, I had everything paid to participate in the course to be the creator. We were going to be the base of the Citizenship territory, mainly in the Madeira Mamoré territory, which would be here in Porto Velho, Guajará-Mirim to Itapuã, in the 5 municipalities.” ____Interviewee EREC01

“It was via Brasília, right … we used to write our own Grito da Terra, Grito da Terra Nacional, it was a national publication. We discussed costs with the federal government, with ministers, all this demand for public policies aimed to family farming. The era of food acquisition, agrarian reform and settlements, health, education, rural housing, there are several items that we discussed within the National Grito. There were 10 thousand, 15 thousand rural workers in Brasília. A committee, we formed 15 days to 30 days before. I participated until 2013. There we first discussed with the minister the demand. Then they said what could be met, what could not be met. Sometimes it was very favorable, sometimes with victories, sometimes not so positive, right.” ____Interviewee ECON01

“Then in 2011 we went from 6 to 182 family farmers, counting on the members, because the cooperative demanded the largest number of members. We had a very high demand, because we went to television when I went to local channel. Those who watched the TV program were participating. We had the corridor full of farmers.” ____Interviewee ESEME01

“ESEME01 is good people and she has been there since the beginning. At the time ESEME01 was from SEMED and I was from SEMAGRIC, so when there were meetings, it was a clash all the time. There was dialogue and it was very good! Things have developed in our time, advanced a lot.” ____Interviewee EEPP01

5.2.3. Consolidation and Inspections in the Period between 2013 and 2020

“There have already been situations of a lot of loss of meals, at a certain time there was an audit by the FNDE and they suggested that it is a loss for the student, it is a loss for the resource. When you arrive at school you have 50 kg of expired beans ready to go to waste to be incinerated … what are we going to do? The principal will be held responsible. That’s where you practically no longer find expired products.” ____Interviewee ECAEM01

“There is a concern on the part of the government to promote family farming, which we already had here through Law No. 3753 [62] and Decree No. 22,177 on fish, we saw that the state, as a state in which fish farming is quite developed. So, we managed to include fish and other foods produced in the state from family farming and cooperatives in school meals and this is very interesting. The return of this is gratifying for those who work in the community project.” ____Interviewee ESED02

“To give support, there is an inter-ministerial ordinance that allows the purchase of products, from the local culture, from the northern region of the state. So, there are some products that are regionalized and with this inter-ministerial ordinance, we have already managed to purchase a lot of products.” ____Interviewee ESED01

“The old way that FNDE did was to transfer to the municipality, right, and each executing unit, each school, opened an account to receive the transfer. So, every school had an account to receive the transfer. Not now, the difference is that the municipality had to open one account, right. The municipality is going to put an end to these accounts, it is going to apply for corporate cards. I like to compare it to an additional card […] actually, SEMED already sent a document in 2019 explaining to principals. For example, School X has this limit … there’s no way to cross this limit. […] The PMAE, at first its continuation in the traditional way was discussed, then it was decided to use a PMAE card. It will continue in the traditional way until the PNAE card stabilizes. At least 6 months this year, right, so that we can overcome any problems that may arise. And then, next year, the PMAE card.” ____Interviewee ESEME03

“It’s going to make life easier for everyone, right... Even yesterday I contacted the FNDE, if there is a demand from people who want to trade, but can’t get the machine, they made an exception for the transfer, it just has to be very well documented that there is no internet where the family farmer is located, the justification for making this exception has to be well founded. But there was also a whole demand, right, which nowadays everyone is already adapted with electronic invoices […] So this guy who issues electronic invoices, at some point he has access to the internet and then he could possibly also use the machine.” ____Interviewee ESEME03

“People have their demand and simply apply. And we have to comply. Now there is that partnership that should be on both sides we don’t have. They simply handed over the card and didn’t even inform … I went informally to inquire, but no one notified me saying that I needed to adapt or anything. So, I believe that in this sense there should be a better partnership, right, to be able to help because the producer suffers too much to produce even more in Porto Velho, it’s not easy. […] There is a cost, right. It’s another bill that the producer will have to pay. I think so … if it’s to improve, I agree, but you also have to look at the producer’s situation and I felt that people have not taken this into account.” ____Interviewee ECFARO01

6. Discussion

“The federal government likes to be provoked. By the provocation we say our need, if we keep quiet, the government is going to think that everything is ok. So, we provoke the governments aiming to say what we need. We go to negotiation waiting to be assisted.” ____Interviewee ECON01

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação (FNDE). Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar (PNAE). Dados da Agricultura Familiar: Aquisições da Agricultura Familiar no período de 2011 a 2016. Brasília/DF, 2019. Available online: https://www.fnde.gov.br/programas/pnae/pnae-consultas/pnae-dados-da-agriculturafamiliar (accessed on 16 November 2019).

- Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação (FNDE). Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar (PNAE). Sobre o PNAE. Brasília/DF, 2019. Available online: https://www.fnde.gov.br/index.php/programas/pnae/pnae-sobre-oprograma/pnae-historico (accessed on 16 November 2019).

- Silva, E.O.; Amparo-Santos, L.; Soares, M.D. Alimentação escolar e constituição de identidades dos escolares: Da merenda para pobres ao direito à alimentação. CSP–Cad. Saúde Pública 2018, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluf, R.S.J.; Luz, L.F. Sistemas Alimentares Descentralizados: Um Enfoque de Abastecimento na Perspectiva da Soberania e Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional. R. Janeiro, UFRRJ/CPDA/OPPA, 2016, 22 p. (Texto de Conjuntura, 19). Available online: http://oppa.net.br/acervo/textos-fao-nead-gpac/Texto%20de%20conjuntura%2019%20-%20Renato%20MALUF%20--%20Lidiane%20DA%20LUZ.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Brasil. Lei Federal nº 11,947 de 16 de junho de 2009. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF, 2009. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2014/Lei/L12982.htm (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Brasil. Resolução nº 26, de 17 de junho de 2013. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 2013. Available online: https://www.fnde.gov.br/index.php/acesso-a-informacao/institucional/legislacao/item/4620-resolu%C3%A7%C3%A3o-cd-fnde-n%C2%BA-26,-de-17-de-junho-de-2013 (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Brasil. Resolução nº 4, de 3 de abril de 2015. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 2015. Available online: https://www.fnde.gov.br/index.php/acesso-a-informacao/institucional/legislacao/item/6341-resolu%C3%A7%C3%A3o-cd-fnde-mec-n%C2%BA-4,-de-3-de-abril-de-2015 (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Brasil. Resolução nº 6, de 8 de maio de 2020. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 2020. Available online: http://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-n-6-de-8-de-maio-de-2020-256309972 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Brasil. Lei Federal nº 8,666 de 16 de junho de 1993. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 1993. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8666cons.htm (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Triches, R.M.; Schneider, S. Alimentação Escolar e agricultura familiar: Reconectando o consumo à produção. Saúde Sociedade 2010, 19, 933–945. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/sausoc/v19n4/19.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia E Estatística (IBGE). Estimativas Populacionais Para os Municípios e Para as Unidades da Federação Brasileiros em 01.07.2017; Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia E Estatística (IBGE): Brasília, Brazil, 2017. Available online: https://ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Populacao/Estimativas_2017/estimativa_dou_2017.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Velho. Acidade. 2019. Available online: https://www.portovelho.ro.gov.br/artigo/17800/a-cidade# (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- Engeström, Y.; Sannino, A. Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings and future challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 2010, 5, 1–24. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248571723_Studies_of_expansive_learning_Foundations_findings_and_future_challenges (accessed on 26 October 2019). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engeström, Y. Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. J. Educ. Work. 2001, 14, 133–156. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13639080020028747 (accessed on 26 October 2019). [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. Learning by Expanding: An Activity Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Peixinho, A.M.L. A trajetória do Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar no período de 2003–2010: Relato do gestor nacional. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2013, 18, 909–916. Available online: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S1413-81232013000400002&script=sci_abstract&tlng=pt (accessed on 26 October 2019). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brasil. Medida Provisória nº 2178-36 de 24 de agosto de 2001. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 2001. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/MPV/2178-36.htm (accessed on 26 April 2019).

- Brasil. Portaria Interministerial nº 1010 de 08 de Maio de 2006. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 2006. Available online: https://repositorio.observatoriodocuidado.org/bitstream/handle/handle/1554/Portaria%20%20Interministerial%20N%c2%ba%201.010_8%20maio%202006.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Brasil. Resolução nº 38, de 16 de julho de 2009. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 2009. Available online: http://educacaointegral.mec.gov.br/images/pdf/res_cd_38_16072009.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Das Neves, J. Módulo introdução: Sobre os CECANES’s. In Formação de Nutricionista para Atuação no PNAE, 2018, 1st ed.; Mafra, R., Ed.; Centro Colaborador de Alimentação e Nutrição do Escolar de Santa Catarina: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2018; pp. 9–26. Available online: https://cecanesc.paginas.ufsc.br/files/2019/07/1.05-Apendice-1.05.-caderno-de-formacao-ead-de-nutricionistas.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Broch, A.E. Congresso Nacional aprova projetos importantes para o MSTTR. J. CONTAG Brasília 2009, 6, 3. Available online: http://www.contag.org.br/imagens/f1620contagmaiojunho.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Brasil Lei Federal nº 10,520, de 17 de julho de 2002. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 2002. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/2002/l10520.htm (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Brasil. Decreto nº 10,024, de 20 de setembro de 2019. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 2019. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/decreto-n-10.024-de-20-de-setembro-de-2019-217537021 (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Brasil. Lei Federal nº 13,987 de 7 de abril de 2020. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF, 2020. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/lei-n-13.987-de-7-de-abril-de-2020-251562793 (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Brasil. Resolução nº 2, de 9 de abril de 2020. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 2020. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-n-2-de-9-de-abril-de-2020-252085843 (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Engeström, Y. From learning environments and implementation to activity systems and expansive learning. Int. J. Hum. Act. Theory 2009, 2, 17–33. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/228665699.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2019).

- Sannino, A. Activity theory as an activist and interventionist theory. Theory Psychol. 2011, 21, 571–597. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0959354311417485 (accessed on 20 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Leontiey, A.N. Problems of the Development of the Mind; Progress: Moscow, Russia, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, M. Cultural Psvchology: A Once and Future Discipline; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, P.; Cole, M. Current activity for the future: The Zo-ped. In Children’s Learning in the “Zone of Proximal Development”, 1st ed.; Rogoff, B., Wertsch, J.V., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1984; pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sampieri, R.H.; Collado, C.F.; Lucio, P.B. Metodologia da Pesquisa, 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill: São Paulo, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Introduction to Qualitative Research. Qualitative Research in Practice: Examples for Discussion and Analysis, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Charreire, S.; Durieux, F. Explorer et tester: Deux voies pour la recherche. In Méthodes de Recherche en Management; Org. Thietart, R.A. et coll; Dunod: Paris, France, 2003; Available online: https://www.dunod.com/sites/default/files/atoms/files/9782100711093/Feuilletage.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Cruz, L.B. O processo de Formação de Estratégias de Desenvolvimento Sustentável de Grupos Multinacionais. Ph.D. Thesis, Doctorate in Administration. Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil, 13 November 2007. Available online: https://lume.ufrgs.br/handle/10183/12416 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design Methods, 6th ed.; Cosmos Corporation–SAGE: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.; Kumar, V.; Day, G. Pesquisa de Marketing, 1st ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Triviños, A.N. Introdução a Pesquisa em Ciências Sociais: A Pesquisa Qualitativa em Educação, 1st ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. Focus on Research Methods Whatever Happened to Qualitative Description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Introdução à Pesquisa Qualitativa, 3rd ed.; Costa, J.E., Translator; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland, J. Styles of reporting qualitative field research. Am. Sociol. 1974, 9, 101–111. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27702128?seq=1 (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Lofland, J.; Lofland, L.H. Analyzing Social Settings: A Guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis, 3rd ed.; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo; Edições 70: São Paulo, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaria Municipal de Educação (SEMED). Relatório Anual do Exercício Financeiro de 2019; Porto Velho: Rondônia, Brazil, 2019.

- Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento Da Educação (FNDE). Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar (PNAE). Alunado por ação do Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar. 2020. Available online: https://www.fnde.gov.br/pnaeweb/publico/relatorioDelegacaoEstadual.do (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- Rondônia. Decreto Estadual nº 23,444, de 18 de dezembro de 2018. Diário Oficial [do] Estado de Rondônia, Porto Velho, RO. 2018. Available online: http://ditel.casacivil.ro.gov.br/COTEL/Livros/Files/D23444.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- Spinelli, M.A.S.; Canesqui, A.M. O programa de alimentação escolar no estado do Mato Grosso: Da centralização à descentralização (1979–1995). Rev. Nutr. 2002, 15, 105–117. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S1415-52732002000100011&script=sci_abstract&tlng=pt (accessed on 14 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Porto Velho. Decreto Municipal nº 5,251, de 10 de Novembro de 1993; Diário Oficial [do] Município de Porto Velho: Porto Velho, Brazil, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Lei nº 8,913, de 12 de julho de 1994. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 1994. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/LEIS/L8913.htm (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Rondônia. Decreto Estadual nº 6,681, de 26 de janeiro de 1995. Diário Oficial [do] Estado de Rondônia, Porto Velho, RO. 1995. Available online: http://ditel.casacivil.ro.gov.br/COTEL/Livros/Files/D6681.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Rondônia. Decreto Estadual nº 6901, de 22 de junho de 1995. Diário Oficial [do] Estado de Rondônia, Porto Velho, RO. 1995. Available online: http://ditel.casacivil.ro.gov.br/COTEL/Livros/Files/D6901.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Rondônia. Lei Estadual Complementar nº 177, de 9 de julho de 1997. Diário Oficial [do] Estado de Rondônia, Porto Velho, RO. 1997. Available online: https://sapl.al.ro.leg.br/media/sapl/public/normajuridica/1997/310/310_texto_integral (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Brasil. Medida Provisória nº 1,784 de 14 de dezembro de 1998. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF, 1998. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/MPV/Antigas/1784.htm (accessed on 26 April 2019).

- Brasil. Lei nº 10,696, de 2 de julho de 2003. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 2003. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/LEIS/2003/L10.696.htm (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Valnier, A.; Ricci, F. Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos (PAA): Uma análise comparativa nos estados de Rondônia e Acre. Campo-Território: Rev. Geogr. Agrária 2013, 8, 198–228. Available online: http://www.seer.ufu.br/index.php/campoterritorio/article/view/21732l (accessed on 2 August 2019).

- Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Velho. Prefeitura reforça alimentação de alunos do campo. 2019. Available online: https://www.portovelho.ro.gov.br/artigo/1974/prefeitura%EF%BF%BEreforca-alimentacao-de-alunos-do-campo (accessed on 23 November 2019).

- Rondônia. Portaria nº 0323/07-GAB/SEDUC, de 18 de janeiro de 2007. Diário Oficial [do] Estado de Rondônia, Porto Velho, RO. 2007. Available online: http://www.diof.ro.gov.br/data/uploads/diarios-antigos/2007-01-23.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Porto Velho. Decreto Lei Municipal nº 12,563, de 26 de março de 2012. Diário Oficial [do] Município de Porto Velho, Porto Velho, RO. 2012. Available online: https://www.portovelho.ro.gov.br/uploads/docman/decreto_n._12.563-12_dispoe_sobre_os_conselhos_es.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Rondônia. Lei Estadual Complementar nº 680, de 7 de setembro de 2012. Diário Oficial [do] Estado de Rondônia, Porto Velho, RO. 2012. Available online: http://www.diof.ro.gov.br/doe/07_SETEMBRO_ESPECIAL.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Brasil. Lei Federal nº 12,982 de 28 de maio de 2014. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF, 2014. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2009/Lei/L11947.htm (accessed on 26 April 2019).

- Rondônia. Decreto Estadual nº 19,115, de 25 de agosto de 2014. Diário Oficial [do] Estado de Rondônia, Porto Velho, RO. 2014. Available online: http://ditel.casacivil.ro.gov.br/COTEL/Livros/Files/DEC19115.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Rondônia. Lei Estadual Complementar nº 829, de 15 de julho de 2015. Diário Oficial [do] Estado de Rondônia, Porto Velho, RO. 2015. Available online: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:OLzkevX5cdUJ:ditel.casacivil.ro.gov.br/COTEL/Livros/Files/LC829.docx+&cd=1&hl=pt-BR&ct=clnk&gl=br (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Rondônia. Lei Estadual nº 3,753, de 30 de dezembro de 2015. Diário Oficial [do] Estado de Rondônia, Porto Velho, RO. 2015. Available online: http://ditel.casacivil.ro.gov.br/COTEL/Livros/Files/L3753.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Velho. Educação. Available online: https://www.portovelho.ro.gov.br/artigo/23270/educacao-prefeitura-aumentara-em-100-o-repasse-a-merenda-escolar-neste-ano-letivo. (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- Rondônia. Decreto Estadual nº 22,179, de 8 de agosto de 2017. Diário Oficial [do] Estado de Rondônia, Porto Velho, RO. 2017. Available online: http://ditel.casacivil.ro.gov.br/COTEL/Livros/Files/D22179.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Ministério da Transparência, Fiscalização E Controle. Programa de Fiscalização em Entes Federativos–V05º Ciclo Número do Relatório: 201801060. Brasília, MTFC, 2018. Available online: https://eaud.cgu.gov.br/relatorios/?colunaOrdenacao=dataPublicacao&direcaoOrdenacao=DESC&tamanhoPagina=15&offset=0&titulo=Programa+de+Fiscaliza%C3%A7%C3%A3o+em+Entes+Federativos+%E2%80%93+V05%C2%BA++Ciclo+N%C3%BAmero+do+Relat%C3%B3rio%3A+201801060&palavraChave=ROND%C3%94NIA%2C+SEDUC#lista (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Brasil. Portaria Interministerial nº 284 de 30 de maio de 2018. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF, 2018. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/29306868/do1-2018-07-10-portaria%EF%BF%BEinterministerial-n-284-de-30-de-maio-de-2018-29306860 (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Brasil. Decreto nº 7,775, de 4 de julho de 2012. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF, 2012. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2012/Decreto/D7775compilado.htm (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Brasil. Resolução nº 59, de 13 de julho de 2013. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF. 2013. Available online: http://www.lex.com.br/legis_24599200_RESOLUCAO_N_59_DE_10_DE_JULHO_DE_2013.aspx#:~:text=Estabelece%20as%20normas%20que%20regem,Alimentos%2C%20e%20d%C3%A1%20outras%20provid%C3%AAncias (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Rondônia. Edital de Chamamento Público nº 008/2020/CEL/SUPEL/RO. [Aquisição de gêneros alimentícios da agricultura familiar e do empreendedor familiar rural para o atendimento do Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar–PNAE e Programa Estadual de Alimentação Escolar–PEALE]. Rondônia: Superintendência Estadual de Licitações -SUPEL, 2019, 8. Available online: http://www.rondonia.ro.gov.br/licitacao/354223/ (accessed on 2 August 2020).

| Institution | Respondent Code | Respondent Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| SEDUC State Department of Education SAE—School Feeding Department | ESED01 | 1. Nutritionist responsible for the PNAE |

| ESED02 | 2. Administrative technician | |

| SEAGRI—State Department of Agriculture | ESEA02 | 3. Administrative technician |

| CAERO—Rondônia State School Feeding Council | ECAE01 | 4. Volunteer member |

| SEMED—Municipal Department of Education | ESEME01 | 5. Nutritionist responsible for contact with farmers |

| DIALE—School Food Division | ESEME02 | 6. Nutritionist for operational activities |

| ESEME03 | 7. Financial administrative | |

| CAEM—Muni. School Feeding Council | ECAEM01 | 8. Volunteer secretary of the council |

| CONTAG/ Porto Velho Rural Workers Union | ECON01 | 9. Union president |

| FETAGRO—Federation of Rural Workers and Family Farmers of Rondônia | EFF01 | 10. Treasurer |

| PROGRESSO fish processing industry | EPP01 | 11. Responsible veterinarian |

| COOPAGROVERDE | ECGREEN01 | 12. President |

| COOPAFARO | ECFARO01 | 13. President |

| RECA—Agricultural and Forestry Cooperative | EREC01 | 14. Cooperative representative in the capital Porto Velho |

| Association of family farmers in the Sector Chacareiro neighborhood | ESCH03 | 15. Associate who attends the PNAE individual modality |

| State Elementary School in the Central Zone with 450 students | EEEFBN01 | 16. Principal |

| District of Nova California State Elementary and Secondary School with 600 students | EEEFMB01 | 17. Principal |

| Rural Municipal School of Elementary Education with 47 students | EMEFRSA01 | 18. Principal |

| Municipal Elementary School in the Central Zone with 800 students | EMEFAFS01 | 19. Principal |

| EMEFAFS02 | 20. Principal Assistant | |

| Municipal Elementary School in the West Zone with 250 students | EMEFPC01 | 21. Principal |

| Questions | Principles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity Systems | Multiple Voices | Historicity | Contradictions | Expansive Cycles | |

| Who is learning? | Activity System between Municipal and State Managers and Family Farmers. | Nutritionists, CAERO, CAEM, SEDUC, SEMED, CONTAG, FETAGRO, CONSED, UNDIME. | Municipal and state managers and farmers. | Changes in attitude of principals and farmers. | |

| Why learn? | Expansion of the space for rural producers. | Balance between federal standards and economic and social needs within the municipality Mediation between local actors. | Historically, pressures from government, unions, civil society and associations, cooperatives, nutritionists emerge. | Contradictions between the subjects of the Activity System regarding rules, division of labor, mediational resources and Conflicts among farmers; a malfunctioning system attracts fewer family producers and offers students less healthy food. | Based on federal legislation, they create municipal and state laws that complement Law No. 11947 focusing on regional development and sustainability. |

| What do you learn? | Law No. 11947, FNDE Resolutions and Normative Instructions. | Rights and duties of subjects in the execution of the PNAE. | Reconcile the laws for the execution of the PNAE with laws for other processes that complement the final result. | Examples of experiences in other regions or departments; different interests of participating actors can be contradictory | Expansion of PNAE through the interaction of the secretariats, CAEM and CAERO, FETAGRO and CONTAG. |

| How do you learn? | Working groups, training offered to civil servants, support from political or union movements. | Courses promoted by MDS, MDA, FNDE and FETAGRO. | They learn through historical processes and analysis of experiences in other regions; including advance federal decisions. | FNDE, TCU, CAERO, CGU, CAEM, MTFC inspections that point out errors in the process. | Learning actions through questioning, analysis, implementation and reflection, including anticipation of future behavior. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

da Silva, E.A.; Pedrozo, E.A.; da Silva, T.N. PNAE (National School Feeding Program) and Its Events of Expansive Learnings at Municipal Level. World 2022, 3, 86-111. https://doi.org/10.3390/world3010005

da Silva EA, Pedrozo EA, da Silva TN. PNAE (National School Feeding Program) and Its Events of Expansive Learnings at Municipal Level. World. 2022; 3(1):86-111. https://doi.org/10.3390/world3010005

Chicago/Turabian Styleda Silva, Eliane Alves, Eugenio Avila Pedrozo, and Tania Nunes da Silva. 2022. "PNAE (National School Feeding Program) and Its Events of Expansive Learnings at Municipal Level" World 3, no. 1: 86-111. https://doi.org/10.3390/world3010005

APA Styleda Silva, E. A., Pedrozo, E. A., & da Silva, T. N. (2022). PNAE (National School Feeding Program) and Its Events of Expansive Learnings at Municipal Level. World, 3(1), 86-111. https://doi.org/10.3390/world3010005