The Interspecific Abundance–Occupancy Relationship in Invertebrate Metacommunities Associated with Intertidal Mussel Patches

Abstract

1. Introduction

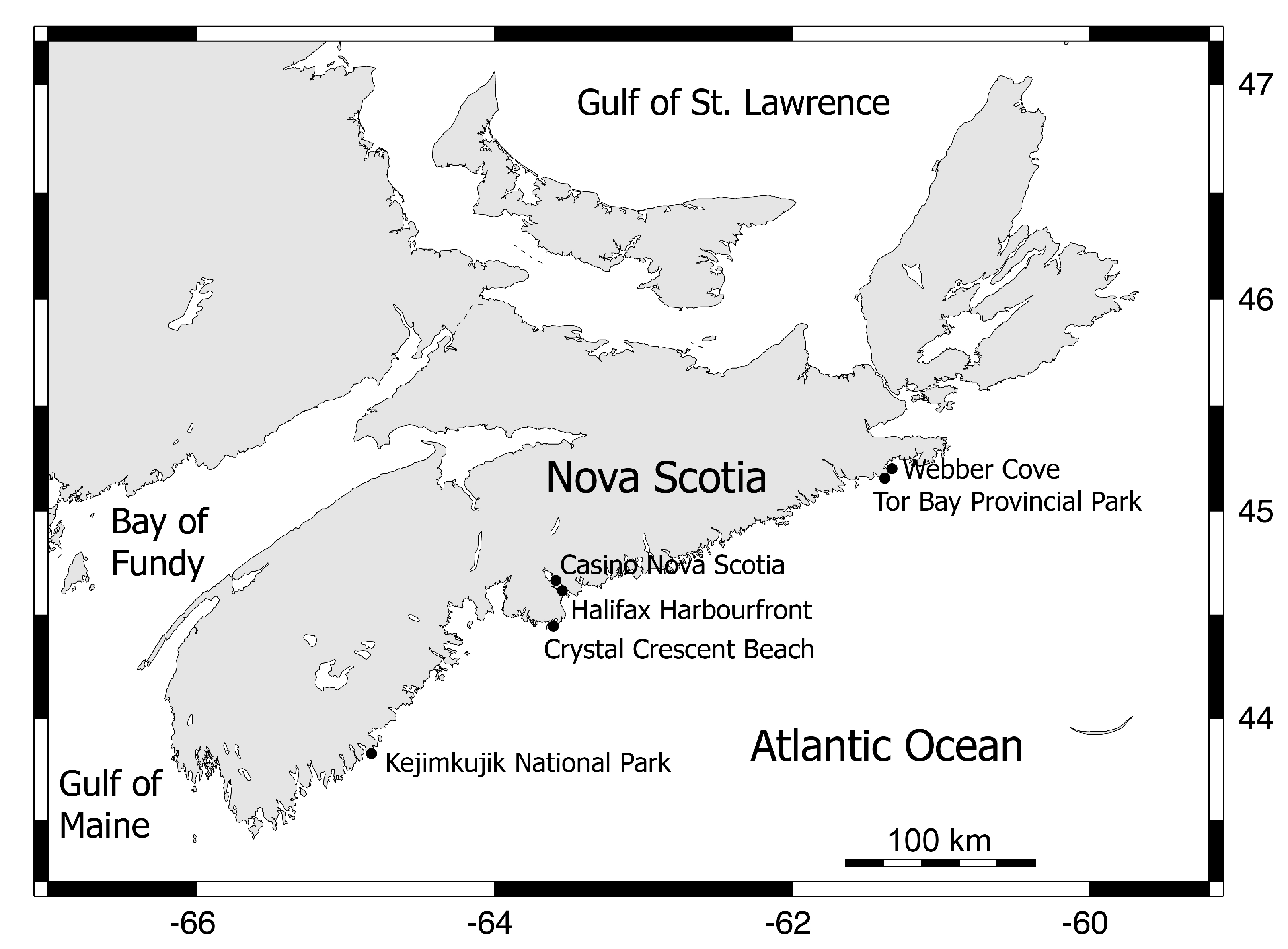

2. Materials and Methods

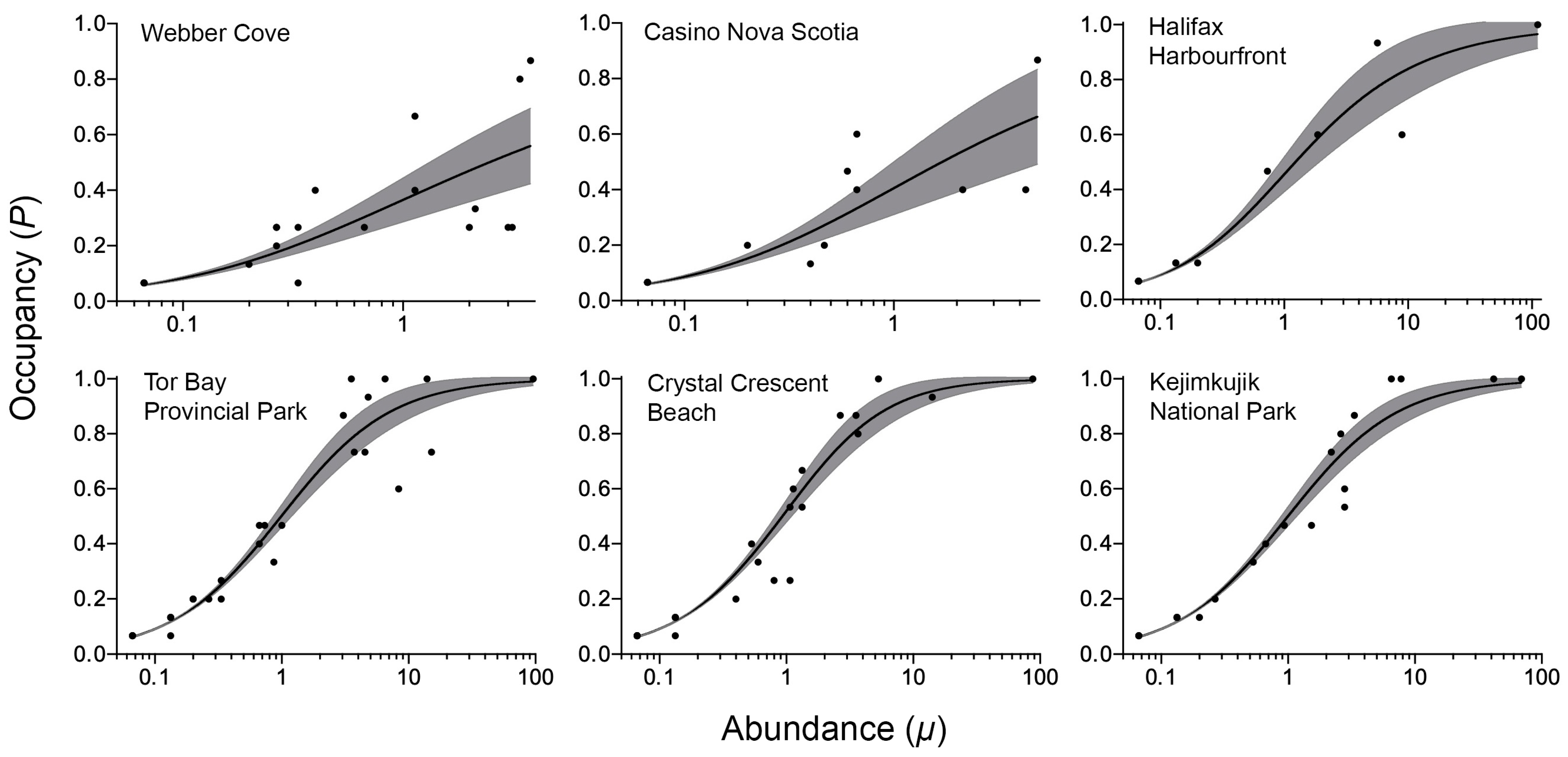

3. Results

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blackburn, T.M.; Cassey, P.; Gaston, K.J. Variations on a theme: Sources of heterogeneity in the form of the interspecific relationship between abundance and distribution. J. Anim. Ecol. 2006, 75, 1426–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izabel-Shen, D.; Höger, A.L.; Jürgens, K. Abundance–occupancy relationships along taxonomic ranks reveal a consistency of niche differentiation in marine bacterioplankton with distinct lifestyles. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 690712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Caten, C.; Holian, L.; Dallas, T. Weak but consistent abundance–occupancy relationships across taxa, space, and time. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2022, 31, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foggo, A.; Bilton, D.T.; Rundle, S.D. Do developmental mode and dispersal shape abundance–occupancy relationships in marine macroinvertebrates? J. Anim. Ecol. 2007, 76, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.J.; Tyler, E.H.M.; Somerfield, P.J. Life history mediates large-scale population ecology in marine benthic taxa. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 396, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, H.L.; Freckleton, R.P. Understanding the role of species dynamics in abundance–occupancy relationships. J. Ecol. 2010, 98, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberk, W.C.E.P.; van der Velde, G.; Esselink, H. Explaining abundance–occupancy relationships in specialists and generalists: A case study on aquatic macroinvertebrates in standing waters. J. Anim. Ecol. 2010, 79, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedo, D.D.; Lamb, E.G. Temporal changes in abundance–occupancy relationships within and between communities after disturbance. J. Veg. Sci. 2013, 24, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulks, L.; Svanbäck, R.; Ragnarsson-Stabo, H.; Eklöv, P.; Östman, Ö. Intraspecific niche variation drives abundance–occupancy relationships in freshwater fish communities. Am. Nat. 2015, 186, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhonen, J.; Jokimaki, J. Temporally stable species occupancy frequency distributions and abundance–occupancy relationship patterns in urban wintering bird asseemblages. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manne, L.L.; Veit, R.R. Temporal changes in abundance–occupancy relationships over 40 years. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boraks, A.; Amend, A.S. Fungi in soil and understory have coupled distribution patterns. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, B.; Akçakaya, H.R. Interspecific variability in demographic processes affects abundance-occupancy relationships. Oecologia 2022, 198, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez, D.; Arribas, P.; Macías-Hernández, N.; Emerson, B.C. Dispersal ability and niche breadth influence interspecific variation in spider abundance and occupancy. Royal Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 230051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matas-Granados, L.; Draper, F.C.; Cayuela, L.; de Aledo, J.G.; Arellano, G.; Ben Saadi, C.; Baker, T.R.; Phillips, O.L.; Honorio Coronado, E.N.; Ruokolainen, K.; et al. Understanding different dominance patterns in western Amazonian forests. Ecol. Lett. 2024, 27, e14351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, R.S.K. Intraspecific abundance–occupancy–patchiness relations in the intertidal benthic macrofauna of a cool-temperate North Sea mudflat. Estuaries Coast. 2022, 45, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, R.S.K. Interspecific abundance-occupancy relations along estuarine gradients. Mar. Environ. Res. 2022, 181, 105755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Genne, B.; Scrosati, R.A. The interspecific abundance–occupancy relationship in rocky intertidal communities. Mar. Biol. Res. 2022, 18, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, D.; Hawkins, S. Intertidal Ecology; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Menge, B.A.; Branch, G.M. Rocky intertidal communities. In Marine Community Ecology; Bertness, M.D., Gaines, S.D., Hay, M.E., Eds.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 221–251. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, N.M.; Scrosati, R.A.; Valdivia, N.; Meunier, Z.D. Global taxonomic and functional patterns in invertebrate assemblages from rocky-intertidal mussel beds. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibold, M.A.; Holyoak, M.; Mouquet, N.; Amarasekare, P.; Chase, J.M.; Hoopes, M.F.; Holt, R.D.; Shurin, J.B.; Law, R.; Tilman, D.; et al. The metacommunity concept: A framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecol. Lett. 2004, 7, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, R.H.; Branch, G.M. Large scale patterns and trophic structure of southern African rocky shores: The roles of geographic variation and wave exposure. J. Biogeogr. 1996, 23, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindegarth, M.; Gamfeldt, L. Comparing categorical and continuous ecological analyses: Effects of wave exposure on rocky shores. Ecology 2005, 86, 1346–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaven, C.S.; Scrosati, R.A. Benthic community composition across gradients of intertidal elevation, wave exposure, and ice scour in Atlantic Canada. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 369, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas, L.P.; Donnarumma, L.; Palomo, M.G.; Scrosati, R.A. Intertidal mussels as ecosystem engineers: Their associated invertebrate biodiversity under contrasting wave exposures. Mar. Biodiv. 2014, 44, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, A.C.; Penniman, C.A.; Harris, L.G. Northwest Atlantic rocky shore ecology. In Intertidal and Littoral Ecosystems (Ecosystems of the World); Mathieson, A.C., Nienhuis, P.H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; Volume 24, pp. 109–191. [Google Scholar]

- Spalding, M.D.; Fox, H.E.; Allen, G.R.; Davidson, N.; Ferdaña, Z.A.; Finlayson, M.; Halpern, B.S.; Jorge, M.A.; Lombana, A.; Lourie, S.A.; et al. Marine ecoregions of the world: A bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. BioScience 2007, 57, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J.C.; Scrosati, R.A. Distribution of cryptic mussel species (Mytilus edulis and M. trossulus) along wave exposure gradients on northwest Atlantic rocky shores. Mar. Biol. Res. 2014, 10, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, D.J.; Bates, J.A. Morphological variation of Mytilus edulis and Mytilus trossulus in eastern Newfoundland. Mar. Biol. 1999, 133, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, H.L.; Scheibling, R.E. Physical and biological factors influencing mussel (Mytilus trossulus, M. edulis) settlement on a wave-exposed rocky shore. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1996, 142, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J.C.; Scrosati, R.A. Mussel and dogwhelk distribution along the north-west Atlantic coast: Testing predictions derived from the abundant-centre model. J. Biogeogr. 2011, 38, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrosati, R.A.; Arribas, L.P.; Donnarumma, L. Abundance data for invertebrate assemblages from intertidal mussel beds along the Atlantic Canadian coast. Ecology 2020, 101, e03137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, A.R.; Gaston, K.J.; He, F. Occupancy–abundance relationships and spatial distribution: A review. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2002, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Gaston, K.J. Estimating species abundance from occurrence. Am. Nat. 2000, 156, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrosati, R.A. Abundance and Occupancy Data for Invertebrate Species Associated to Intertidal Mussel Patches. Figshare Dataset. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertness, M.D. Atlantic Shorelines: Natural History and Ecology; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti-Cecchi, L.; Trussell, G.C. Intertidal rocky shores. In Marine Community Ecology and Conservation; Bertness, M.D., Bruno, J.F., Silliman, B.R., Stachowicz, J.J., Eds.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, S.J.; Pack, K.E.; Firth, L.B.; Mieszkowska, N.; Evans, A.J.; Martins, G.M.; Åberg, P.; Adams, L.C.; Arenas, F.; Boaventura, D.M.; et al. The intertidal zone of the north-east Atlantic region: Pattern and process. In Interactions in the Marine Benthos: Global Patterns and Processes; Hawkins, S.J., Bohn, K., Firth, L.B., Williams, G.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 7–46. [Google Scholar]

- Menge, B.A.; Caselle, J.E.; Milligan, K.; Gravem, S.A.; Gouhier, T.C.; White, J.W.; Barth, J.A.; Blanchette, C.A.; Carr, M.H.; Chan, F.; et al. Integrating coastal oceanic and benthic ecological approaches for understanding large-scale meta-ecosystem dynamics. Oceanography 2019, 32, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menge, B.A.; Sutherland, J.P. Community regulation: Variation in disturbance, competition, and predation in relation to environmental stress and recruitment. Am. Nat. 1987, 130, 730–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellend, M. The Theory of Ecological Communities; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Viana, D.S.; Chase, J.M. Spatial scale modulates the inference of metacommunity assembly processes. Ecology 2019, 100, e02576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovaskainen, O.; Rybicki, J.; Abrego, N. What can observational data reveal about metacommunity processes? Ecography 2019, 42, 1877–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurman, L.L.; Barner, A.K.; Garcia, T.S.; Chestnut, T. Testing the link between species interactions and species co-occurrence in a trophic network. Ecography 2019, 42, 1658–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, F.G.; Cazelles, K.; Gravel, D. Co-occurrence is not evidence of ecological interactions. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23, 1050–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menge, B.A. Indirect effects in marine rocky intertidal interaction webs: Patterns and importance. Ecol. Monogr. 1995, 65, 21–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | k (95% C.I.) | Adjusted R2 (p) | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Webber Cove (wave-sheltered) | 0.32 (0.13–0.51) | 0.51 (0.0004) | 20 |

| Halifax Harbourfront (wave-sheltered) | 0.65 (0.29–1.02) | 0.94 (<0.0001) | 12 |

| Casino Nova Scotia (wave-sheltered) | 0.43 (0.11–0.76) | 0.67 (0.0006) | 13 |

| Tor Bay Provincial Park (wave-exposed) | 1.02 (0.59–1.45) | 0.92 (<0.0001) | 28 |

| Crystal Crescent Beach (wave-exposed) | 1.23 (0.66–1.79) | 0.94 (<0.0001) | 24 |

| Kejimkujik National Park (wave-exposed) | 1.00 (0.64–1.36) | 0.95 (<0.0001) | 22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scrosati, R.A. The Interspecific Abundance–Occupancy Relationship in Invertebrate Metacommunities Associated with Intertidal Mussel Patches. Ecologies 2025, 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6010004

Scrosati RA. The Interspecific Abundance–Occupancy Relationship in Invertebrate Metacommunities Associated with Intertidal Mussel Patches. Ecologies. 2025; 6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleScrosati, Ricardo A. 2025. "The Interspecific Abundance–Occupancy Relationship in Invertebrate Metacommunities Associated with Intertidal Mussel Patches" Ecologies 6, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6010004

APA StyleScrosati, R. A. (2025). The Interspecific Abundance–Occupancy Relationship in Invertebrate Metacommunities Associated with Intertidal Mussel Patches. Ecologies, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6010004