Abstract

This research explores the application of model order reduction (MOR) techniques for blast wave propagation and mitigation. Blast waves, with their rapid pressure changes and highly nonlinear behavior, pose significant challenges for predictive modeling. MOR, a mathematical dimensionality reduction technique, offers a solution by simplifying the complexity of large-scale dynamical systems described by differential equations. These systems can be computationally expensive to solve through conventional numerical schemes. MOR creates a reduced-order model (ROM) that retains the essential features and behavior of the original system but with fewer degrees of freedom. Unlike traditional high-fidelity simulations that are accurate but computationally expensive, MOR allows for multi-query scenarios. This approach significantly reduces computational demands without sacrificing accuracy, making it a valuable tool for engineers and professionals in safety engineering and defense planning. The study also enables the creation of reduced-order models based on high-fidelity simulations of blast wave interactions with structures, promoting their broader adoption in safety planning and structural assessments.

1. Introduction

The full resolution of coupled engineering problems often requires significant computational resources. Traditional numerical methods like finite element, finite volume and spectral methods can effectively solve these engineering problems [1]. On the other hand, they create computationally expensive numerical problems, which are time consuming and memory demanding, particularly in multi-query or real-time scenarios, due to the high number of degrees of freedom (DOFs) involved. Engineering design often requires performing parametric studies where the same equation should be solved multiple times for some varying parameters μ within the design domain. These parameters may be boundary conditions, initial conditions, material properties, geometric features, source terms, or varying loads. Recently, techniques such as the dimensionality reduction in the partial differential equation (PDE) gained significant attention. In particular, reduced-order models (ROMs) aim to reduce this computational burden by constructing a lower-dimensional approximation of the original system, enabling faster computations while maintaining acceptable accuracy. Among these, the Reduced Basis (RB) method emerged as one of the most popular and used [1]. The RB methodology assumes that the parameterized solution of the PDE can be represented on a lower-dimensional manifold, which can be described by a linear subspace spanned by a particular set of basis functions [2]. Two common techniques for generating these functions are Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) and greedy algorithms. POD extracts the most energetic modes from a collection of high-fidelity numerical simulations of the governing equations of the system under investigation. Greedy algorithms, on the other hand, are more efficient in exploring the parameter space by iteratively selecting basis functions that maximize approximation quality. The resulting reduced basis is then employed to project the governing equations onto a smaller set of DOFs, leading to significant reductions in computational cost. Most RB methods follow an offline–online paradigm. In the offline phase, a reduced space is created using “snapshots”, i.e., high-fidelity solutions at selected parameter values. The reduced space is exploited in the online phase to quickly approximate solutions for new parameter values. However, for complex nonlinear problems, traditional projection-based RB methods may not be efficient due to the high cost of computing projection coefficients. MOR techniques can be divided into intrusive and non-intrusive. The former requires complete access to the full-order model (FOM) equations and operators; the latter does not require this information but uses data-driven strategies to approximate the ROM based on the input–data relationship. Therefore, non-intrusive RB methods provide an alternative by using interpolation techniques to avoid directly projecting the full-order system. There is a recent interest in generating completely non-intrusive models without the need for access to high-fidelity problem operators to establish surrogate models. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) have emerged as a popular solution to represent a nonlinear map for describing the trajectory of the POD basis coefficients evolving over time. The projection data train the NN, i.e., choosing its weights to best fit the data in the POD-spanned reduced-order space. Therefore, this peculiar model reduction technique is referred to as POD-ANN [3]. The present work investigates applying POD-ANN to reduce the computational complexity of a common problem in protective engineering: the impact of a blast wave on a plate. The governing PDEs in such problems are parameterized by several variables, making real-time evaluations computationally expensive. In addition, the spatial and temporal resolution to correctly capture phenomena such as shock and fast transient loads is very high, leading to high-fidelity models that can become massive. For the sake of simplicity, this work is limited to a representative case with just two parameters: the time and the explosive charge mass. The structure of this work is as follows. The Section 2 describes the case study under consideration and details the procedures for implementing the POD-NN model reduction. Section 3 presents the numerical findings for the case study, while the Section 4 and Section 5 report the discussion and the conclusions of this research, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

This section is organized into two subsections. The first describes the finite element model and the second delves into implementing the adopted non-intrusive model order reduction framework.

2.1. Case Study: Blast-Loaded Steel Plate

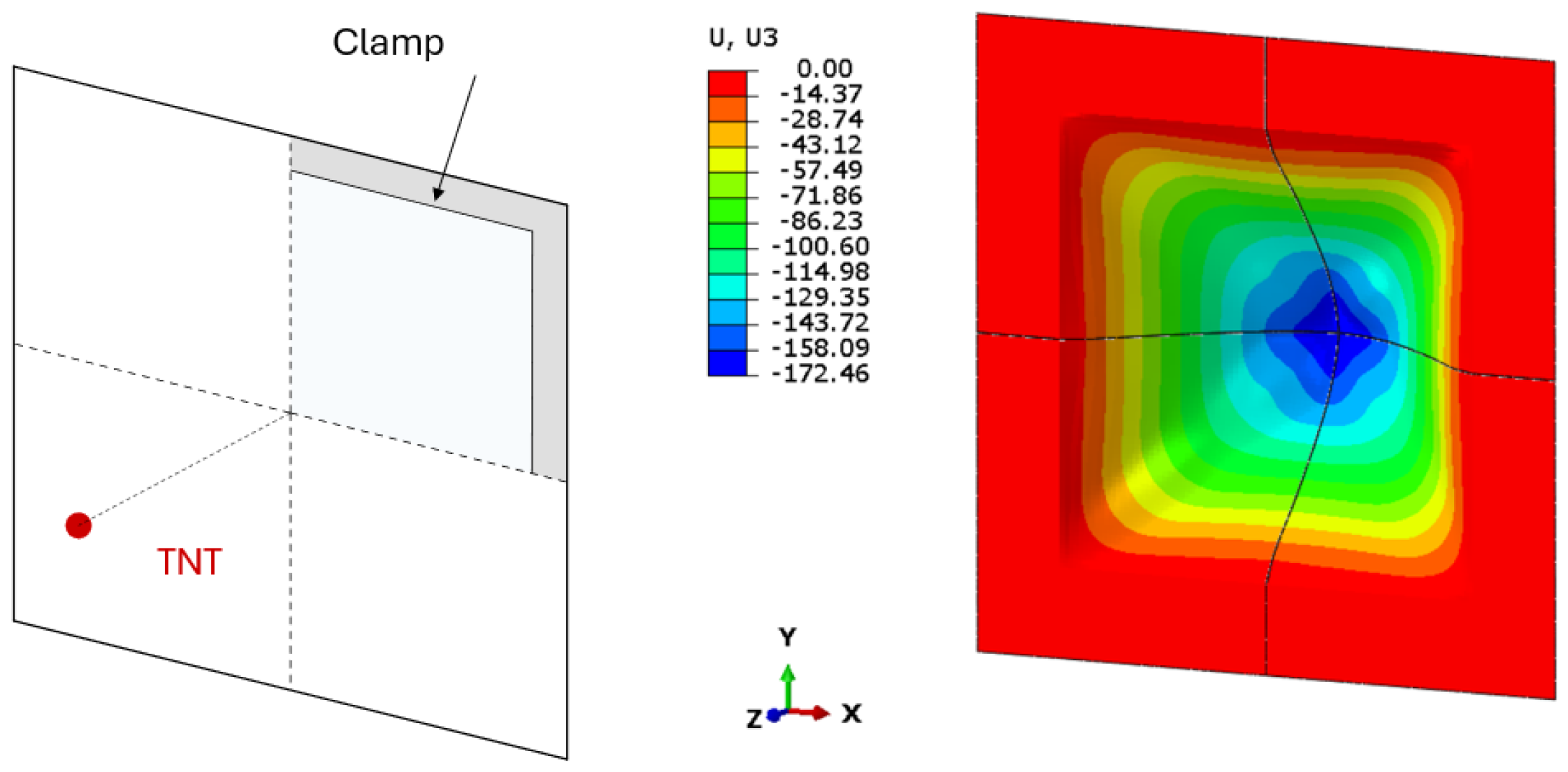

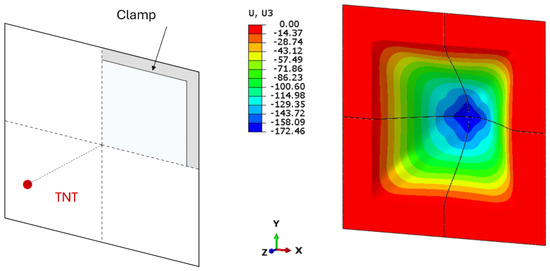

As a simple case study, a steel sheet made of Weldox 500E, produced by Swedish Steel AB (SSAB), is considered. The metal sheet is assumed to be 1 mm thick with an area of 700 × 700 mm2. The exposed area, free to deflect when subjected to blast loading, is 500 × 500 mm2 because of the boundary conditions. The plate is indeed constrained by a clamp, which replicates the effect of bolted joints. All around the border, there is a portion of the plate with a width of 100 mm where all displacement and rotations are prevented because of the encastre constraint. Then, a spherical TNT charge is placed at a stand-off distance of 1800 mm. Due to the double planar symmetry of the model’s geometry, load, and boundary conditions, only one quarter of the sheet is simulated. The built-in CONWEP [4] algorithm is used to model the interaction between blast waves and structures. Figure 1 shows the complete model representation. On the left, it is possible to see a schematic representation of the problem, while on the right, the displacement field induced by the explosion is shown. The construction of the snapshot matrix that stores all the solutions computed in the high-fidelity finite element framework is realized by varying the mass of the explosive. Indeed, the mass of the TNT charge ranges from 1 kg to 5 kg with increments of 0.1 kg for each of the simulations performed. As a result, the full-order model consists of 41 numerical simulations, where the parameter varied is the TNT charge mass, while all other conditions remain constant.

Figure 1.

Geometrical details of the case study (left) and final permanent deformed shape (right). All values are expressed in mm.

When the explosive detonates, it generates a blast wave, represented as a pressure wave applied to the structure, exerting a force on it. Such extreme loading on the structure may lead to plate rupture, plastic permanent deflection or elastic oscillations. Based on the reference system selected, as shown in Figure 1 (right), the permanent deflection is conventionally considered negative. No experimental validation is pursued in this case because this is out of the scope of this work. Indeed, this case is considered a representative scenario to assess the feasibility of an ROM framework for blast-related problems. In particular, the mass and stand-off distance are chosen to ensure that no plate rupture occurs while producing permanent plastic deformations, even in the least severe case, rather than just elastic oscillation. The software Abaqus Explicit [5] is used to model the blast wave’s effect on the structure with each numerical simulation set to a total time of 20 ms. The elastoplastic behavior of the steel is described using the Johnson–Cook constitutive law [6] reported in Equation (1):

Material data are obtained from the literature, specifically from Weldox 500E from Ref. [7], as reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Johnson–Cook material constants for Weldox 500E [7].

Other properties needed for modeling the material, such as elastic or physical properties, are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

General material constants for Weldox 500E [7].

The elastic modulus E and the Poisson’s ratio describe the elastic behavior of the material, is the density, is the specific heat capacity and is the fraction of plastic work converted into heat. The model is meshed with shell elements of type S4, which is a 4-node doubly curved general-purpose shell suitable for finite membrane strains. The mesh is structured and uniform, and all elements have a size equal to 5 mm. Convergence analysis revealed that this element size is adequate to capture the stress gradient while providing a reasonable compromise in terms of computational cost.

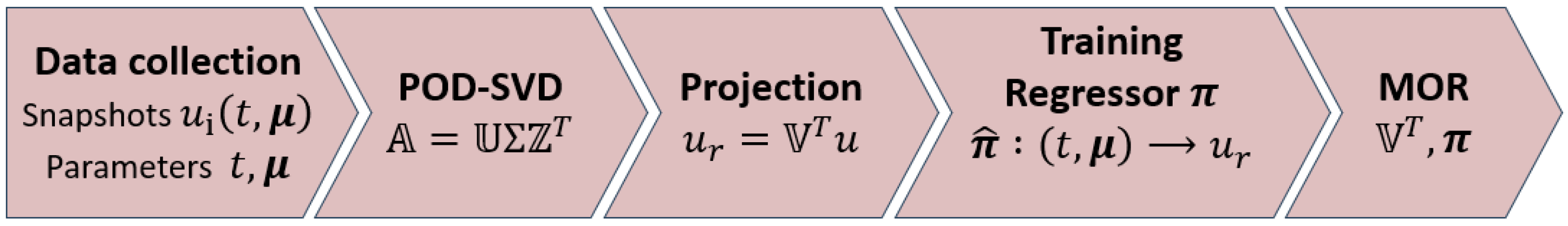

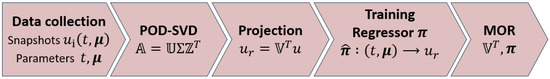

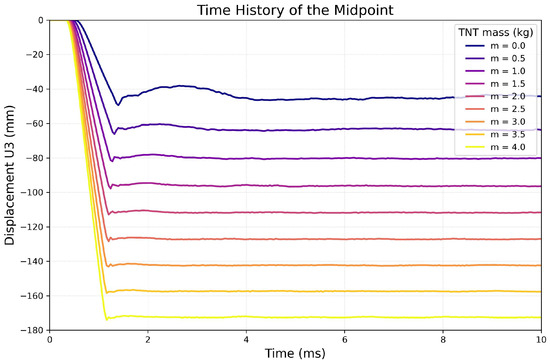

2.2. Model Order Reduction Framework

This work’s model order reduction (MOR) technique is classified as non-intrusive because it relies solely on a data-driven approach without requiring any information about the numerical solver used in the full-order model. In addition to constructing the reduced basis, the non-intrusive MOR employs a regression model as a surrogate for querying new solutions. This meta-model approximates the full-order system within the subspace defined by the reduced basis [3,8]. Figure 2 shows the stages in order to define the offline phase of a non-intrusive MOR.

Figure 2.

Workflow for offline stage in non-intrusive MOR.

In particular, the needed steps are outlined more in detail below:

- Collection of meaningful data from the FOM. A snapshot matrix is built by collecting all displacement fields computed with the full-order analyses as reported in Equation (2).Each displacement field represents the solution evaluated at different times and TNT charge masses . The collected data should represent all possible behaviors that can be replicated later in the ROM. The dimensions of this matrix are where N is the number of DOF of the FOM, i.e, the unknown of the system, is the number of parameter evaluations that are computed through the FOM and is the number of time-steps recorded from the finite element simulation.

- POD is performed on snapshot matrix . The first step is to perform the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD), which leads to a factorization of the snapshot matrix as shown in Equation (3):where and are called singular matrices. is a matrix where the singular values are stored. Column vectors of are called modes of the matrix. The projection matrix is constructed by taking the nth column of the matrix . The procedure of collecting the first n modes from to , as reported in Equation (4), is defined as the POD of a matrix.

- Thanks to matrix , it is now possible to perform the solution projection from the full-order model into the reduced space. The dimensionality decrease from the original size to a dimension equal to the truncated value of n is given by being a rectangle matrix in the most general case. The full-order solution projection onto a lower dimensional space can express the value u as a linear combination of the new basis that spans the reduced space and the combination coefficient. From linear algebra, it holds that combination coefficients are the reduced representation of the full solution onto the space . The original solution can be easily retrieved as a linear combination of the reduced basis vector, collected in , and the coefficient of combination is . Indeed, Equation (5) holds:

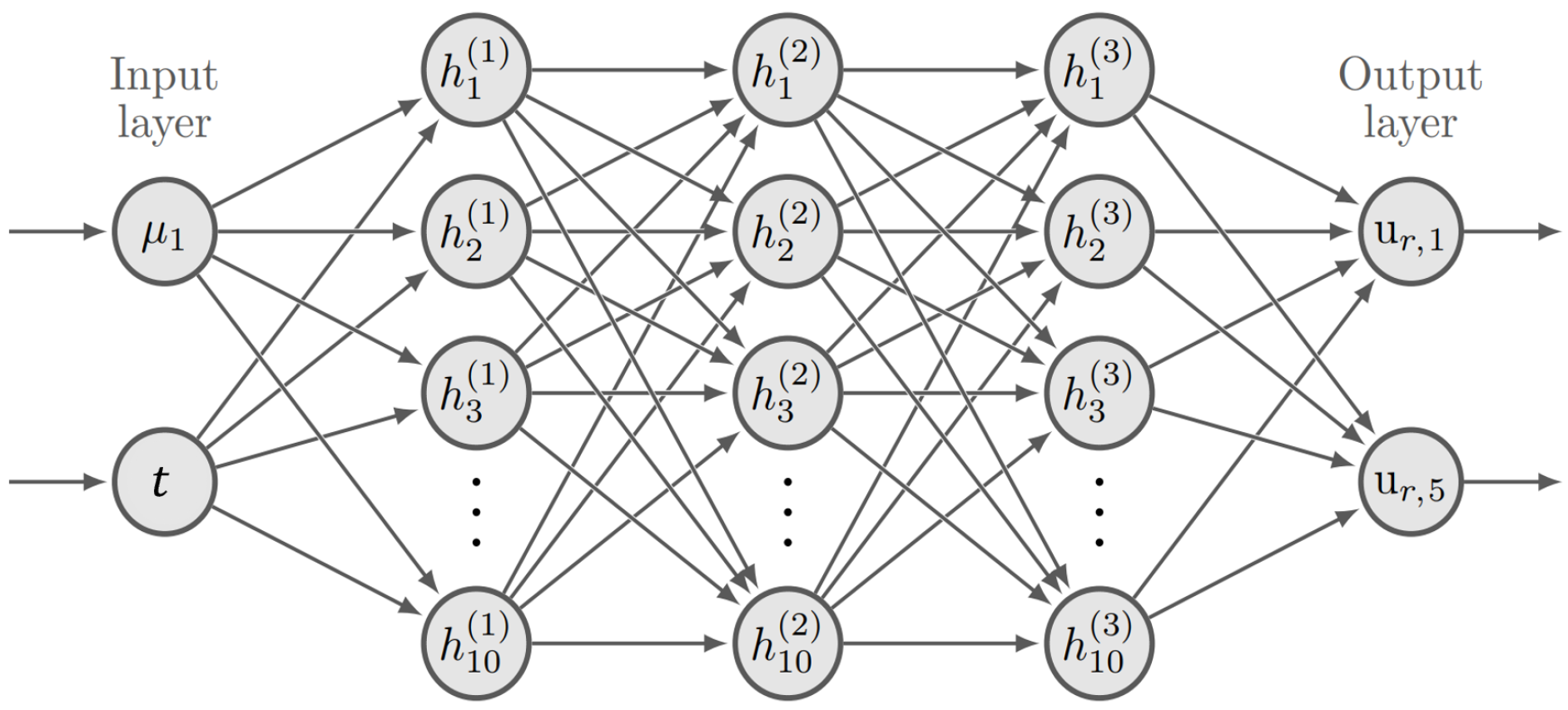

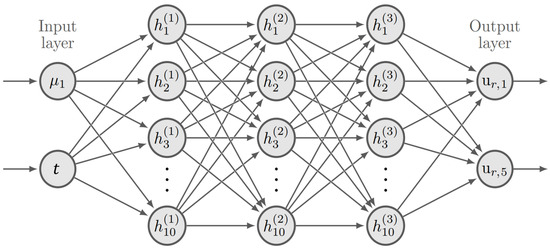

- The previous step allows processing information made available by the FOM. However, to deal with a query of parameters the model has never computed, it is necessary to learn a nonlinear map whose input is the set of parameters t and μ, while the output is the solution represented in the reduced space . The nonlinear mapping can be approximated by a neural network , which learns the nonlinear map relationship between the given input and output as reported in Equation (6):Time t is considered a scalar value included in the interval where T is the ending time of the simulation. On the other hand, μ is a vector belonging to the space of parameters P. The Cartesian product between these two quantities gives origin to all the possible combinations of inside the design space . The neural network aims to learn how to map from these combinations to the corresponding solution in the reduced space. The problem can be defined as a regression problem solved via a supervised learning approach. Figure 3 shows this work’s fully connected deep neural network.

Figure 3. Fully connected neural network used in the regression phase in the MOR.Indeed, for this case, a dense, fully connected neural network with 2 inputs and 5 outputs is considered a suitable architecture. Three hidden layers are introduced, each of them with 10 neurons and with a ReLU activation function. The input is the time, which is always considered a parameter in this scenario, and the mass of TNT. The parameter can be a vector in the more general case, but in this case, it is a scalar value. Table 3 summarizes the ANN architecture.

Figure 3. Fully connected neural network used in the regression phase in the MOR.Indeed, for this case, a dense, fully connected neural network with 2 inputs and 5 outputs is considered a suitable architecture. Three hidden layers are introduced, each of them with 10 neurons and with a ReLU activation function. The input is the time, which is always considered a parameter in this scenario, and the mass of TNT. The parameter can be a vector in the more general case, but in this case, it is a scalar value. Table 3 summarizes the ANN architecture. Table 3. Artificial Neural Network architecture.

Table 3. Artificial Neural Network architecture. - The definition of both a projection matrix and a regression map make it possible to perform model order reduction via the POD-NN approach.

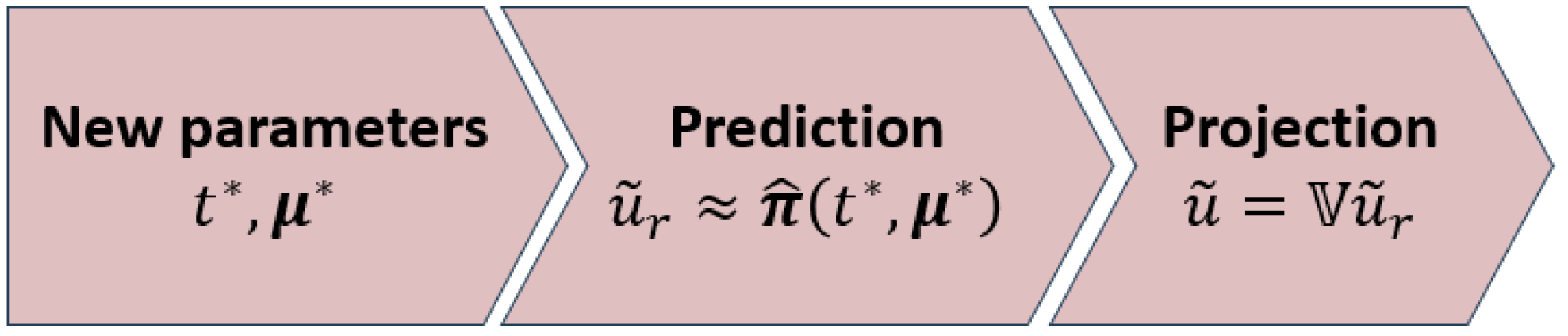

Once the training phase is over, the model can be deployed in the online stage. The dimensionality of the FOM, which was already addressed in the offline stage, no longer leads to the complexity of the computation. In particular, the online phase is structured into a 2-stage workflow. Firstly, the prediction for the new query is performed, and then the projection matrix is applied to reconstruct the solution in the original problem domain. Figure 4 shows the online stage of a non-intrusive ROM.

Figure 4.

Workflow for online stage in non-intrusive ROM.

To exploit this new architecture, the following steps are required:

- Define a new set of parameters and which must be computed. These can be parameters already considered in the snapshot matrix, never computed parameters or a combination of both cases.

- A fast query to the model can be addressed. The neural network can compute the solution corresponding to selected parameters in the reduced space as expressed in Equation (7).

- The predicted solution in reduced space is just a vector whose components are the coefficient in combination with the reduced basis, and by performing the projection with , it is possible to retrieve the solution expressed in the original space but at a lower computational cost.

The problem selected for this work in real engineering applications should not require dimensionality reduction due to its limited domain. Still, it was selected as an example problem for fast transient phenomena to show that ROM is successful. Indeed, three vectors should be defined as in Equation (8):

where the size of the first vector is given by the spatial resolution at which the time is stored, the size of the second vector depends on the parameter change in different scenarios, and the last vector’s dimension is due to the spatial resolution of the mesh on the steel plate. The resulting snapshot matrix for this case study is . The ROM framework is implemented in Python using the library dlrom [9].

3. Results

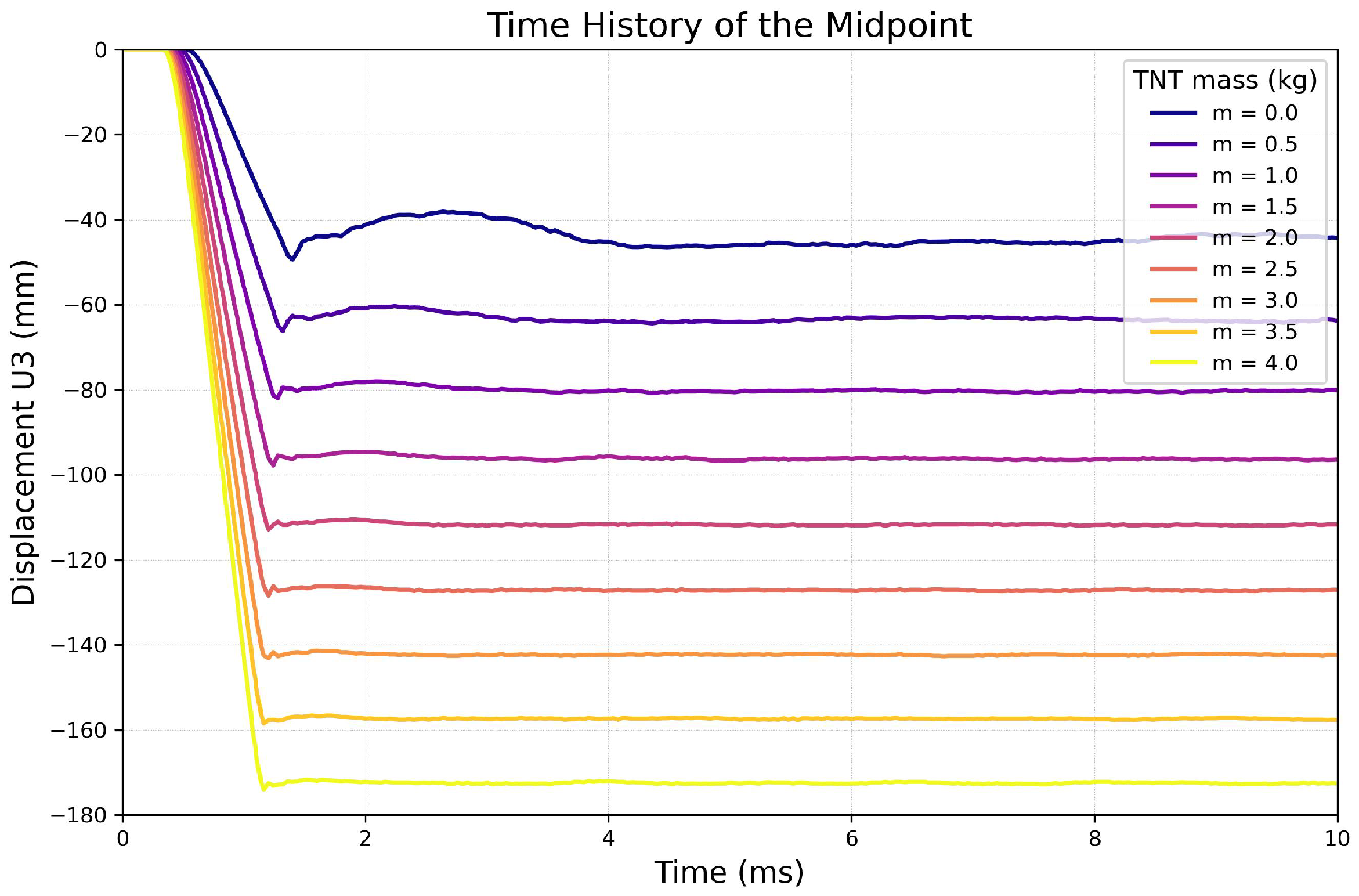

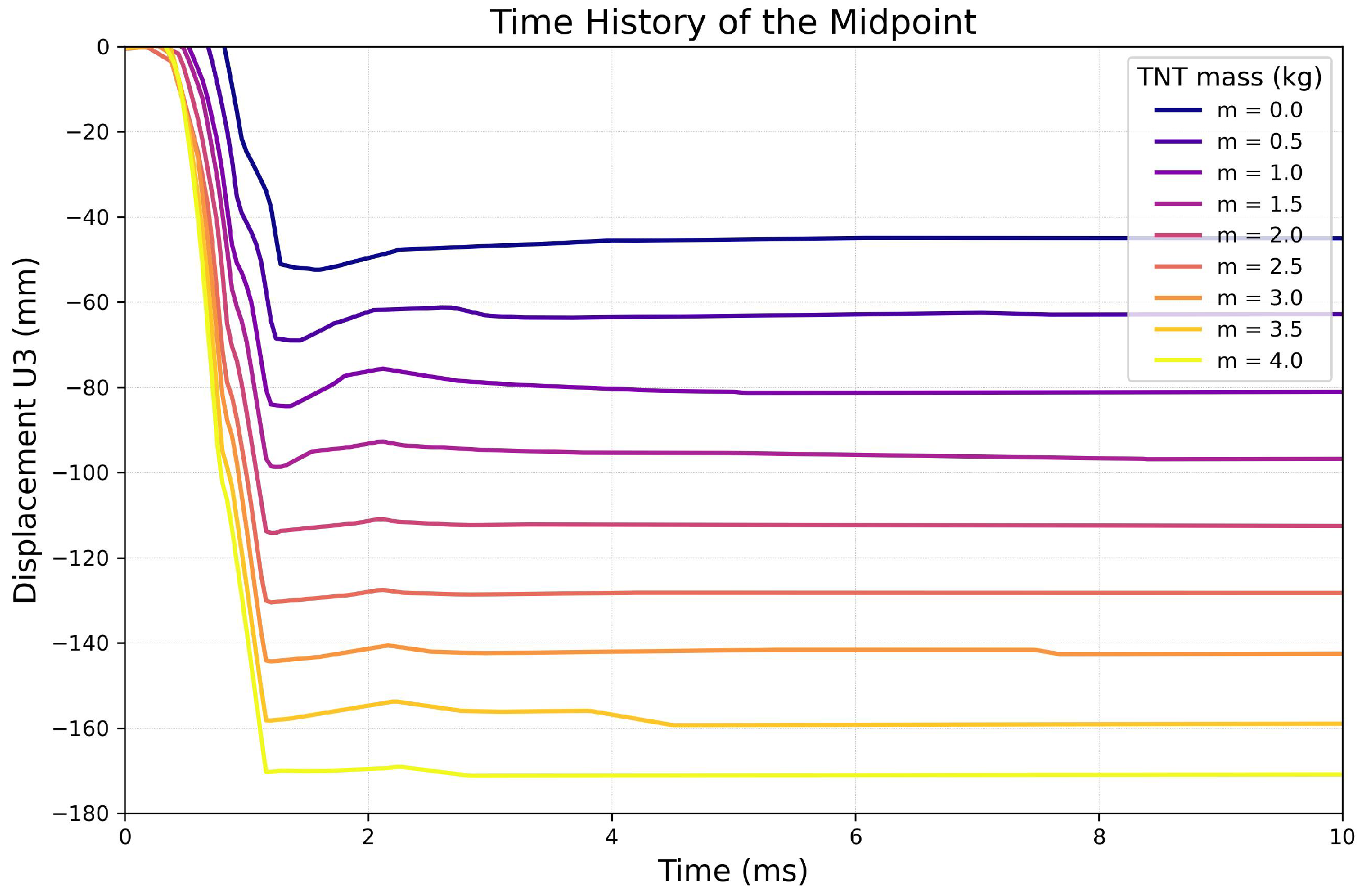

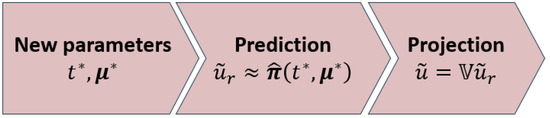

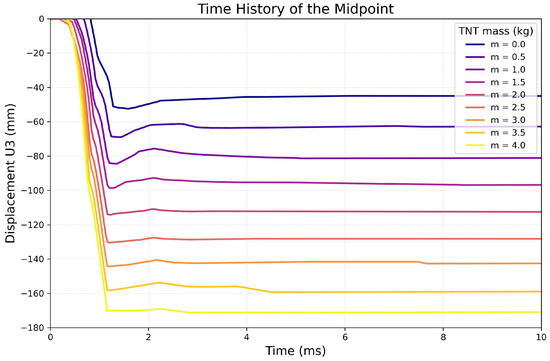

This section presents results by combining the case study and the previously introduced MOR framework. Finite element simulations are performed according to the plan defined previously in order to have enough data to populate the snapshot matrix . It is trivial to state that higher loading causes larger plastic deformation of the metal sheet, resulting in greater permanent deflection. This trend is clearly visible in Figure 5, which shows the deflection for selected TNT masses.

Figure 5.

Displacement vs. time of the midpoint for several values of TNT mass.

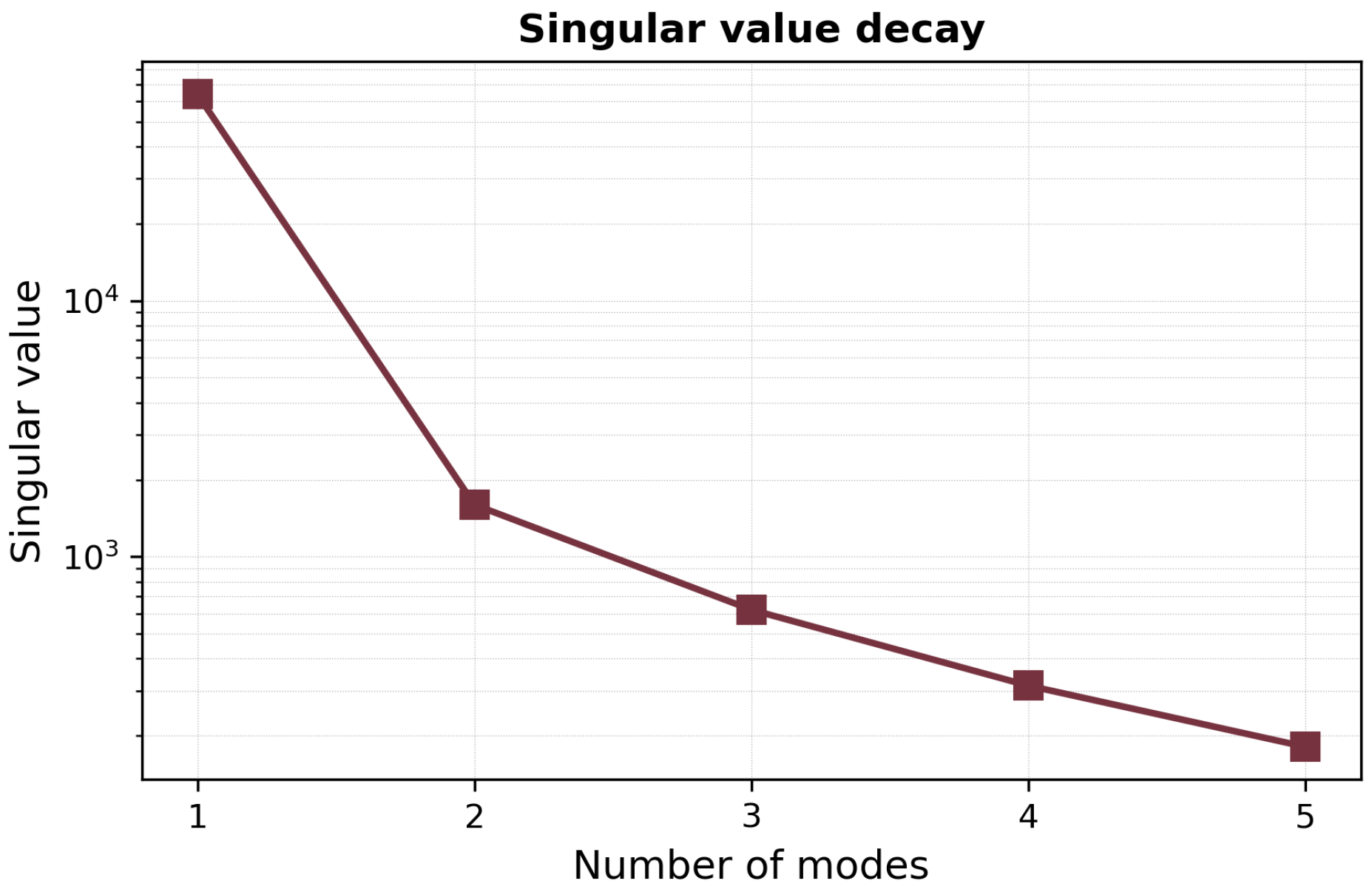

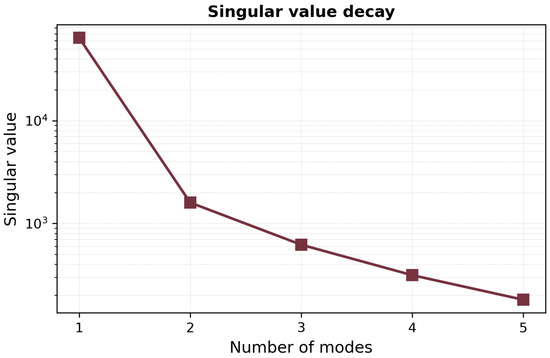

After an initial transient phase where the blast wave interacts with the structure, the dynamic load ceases, leaving only a permanent deflection of the structure. Figure 6 shows the magnitude of the singular values retrieved from the matrix Σ considering the first five modes.

Figure 6.

Singular value decay in logarithmic plot.

Indeed, the approximation is truncated to five modes to build the ROM. In order to evaluate the degree of approximation introduced by the truncation and the linear projection, a projection error is defined in Equation (9). is the ith node of the complete model. These values undergo two linear transformations through the projection matrix . The error is defined as an average considering all points and their normalized distance between the full-order solution, , and the correspondent solution retrieved starting from the POD approach, i.e., . Assuming that the dimension of is 51 × 5, i.e., just five modes are selected, and the projection error is 0.29%. Therefore, five modes are considered an adequate number of modes to represent the plate dynamic compared to the 51 spatial coordinates of the original problem.

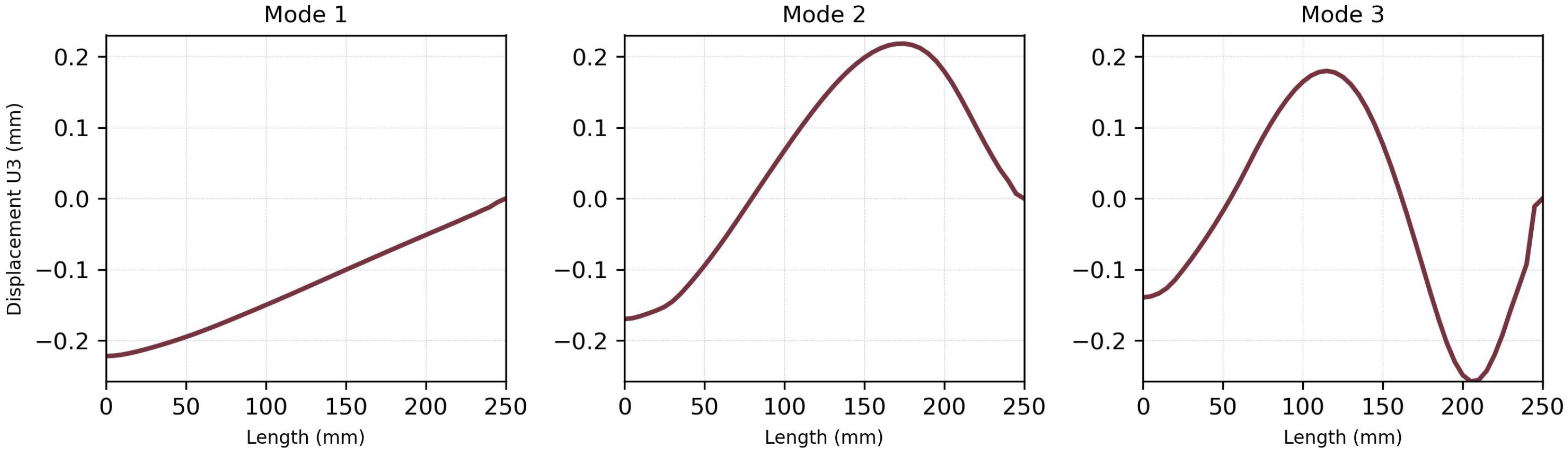

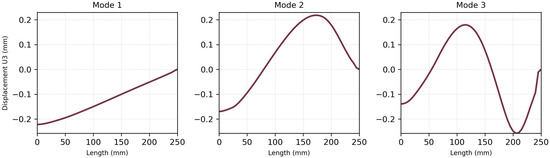

Each of the nth singular values stored in the matrix Σ is associated with a mode, which is the nth column vector of . Figure 7 contains the first three modes, and it is possible to associate them with a physical interpretation for the problem under consideration.

Figure 7.

First 3 modes for the problem when POD is performed.

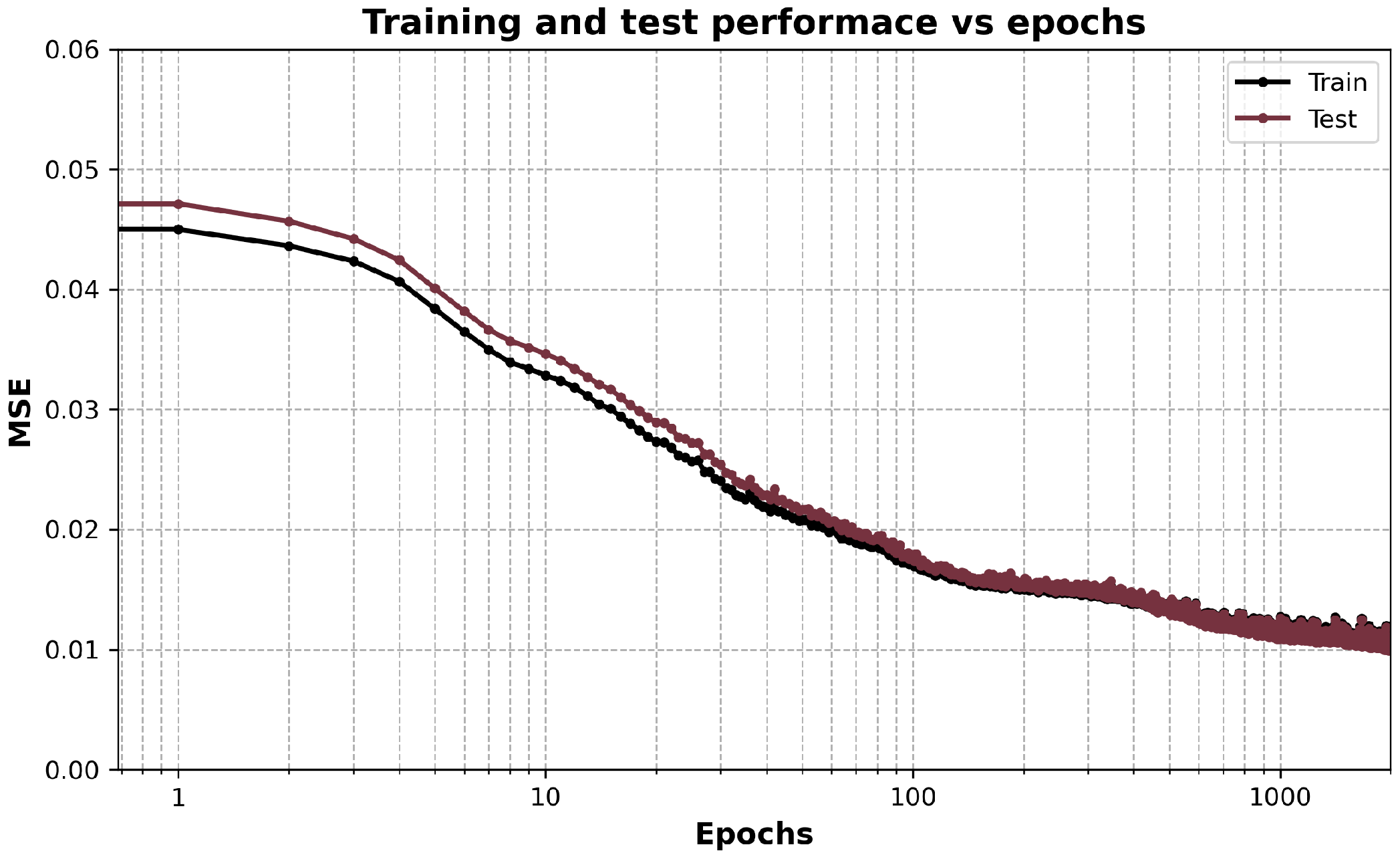

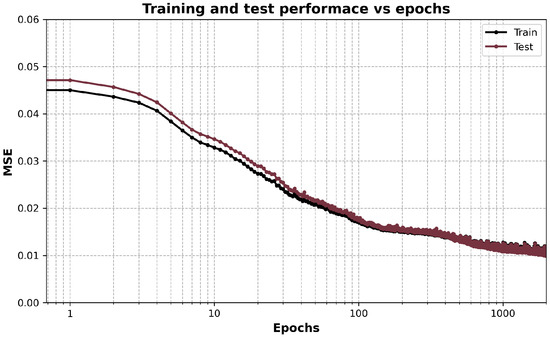

The first mode captures the deformed shape of the plate, while the higher modes are oscillatory ones where the frequency increases by increasing the mode number. The reduced dimensionality can be interpreted as a linear combination of such modes where the first one is responsible for the permanent final deformation multiplied by an adequate scale factor, while the others are responsible for describing the dynamical loading experienced during the transient load of the blast wave. Combining all these reduced bases leads to the reconstruction of the full-order model response with a lower number of DOFs. The snapshot matrix is divided into two subsets for training and testing purposes in a randomized way to promote an efficient learning phase. The training stage is performed over 2000 epochs, and the performance over the training and test sets are reported in Figure 8. The loss function is expressed as the Mean Square Error (MSE); the final values for train and testing, respectively, are equal to 0.01038% and 0.01049%.

Figure 8.

MSE decrease during the training and test stage of the neural network.

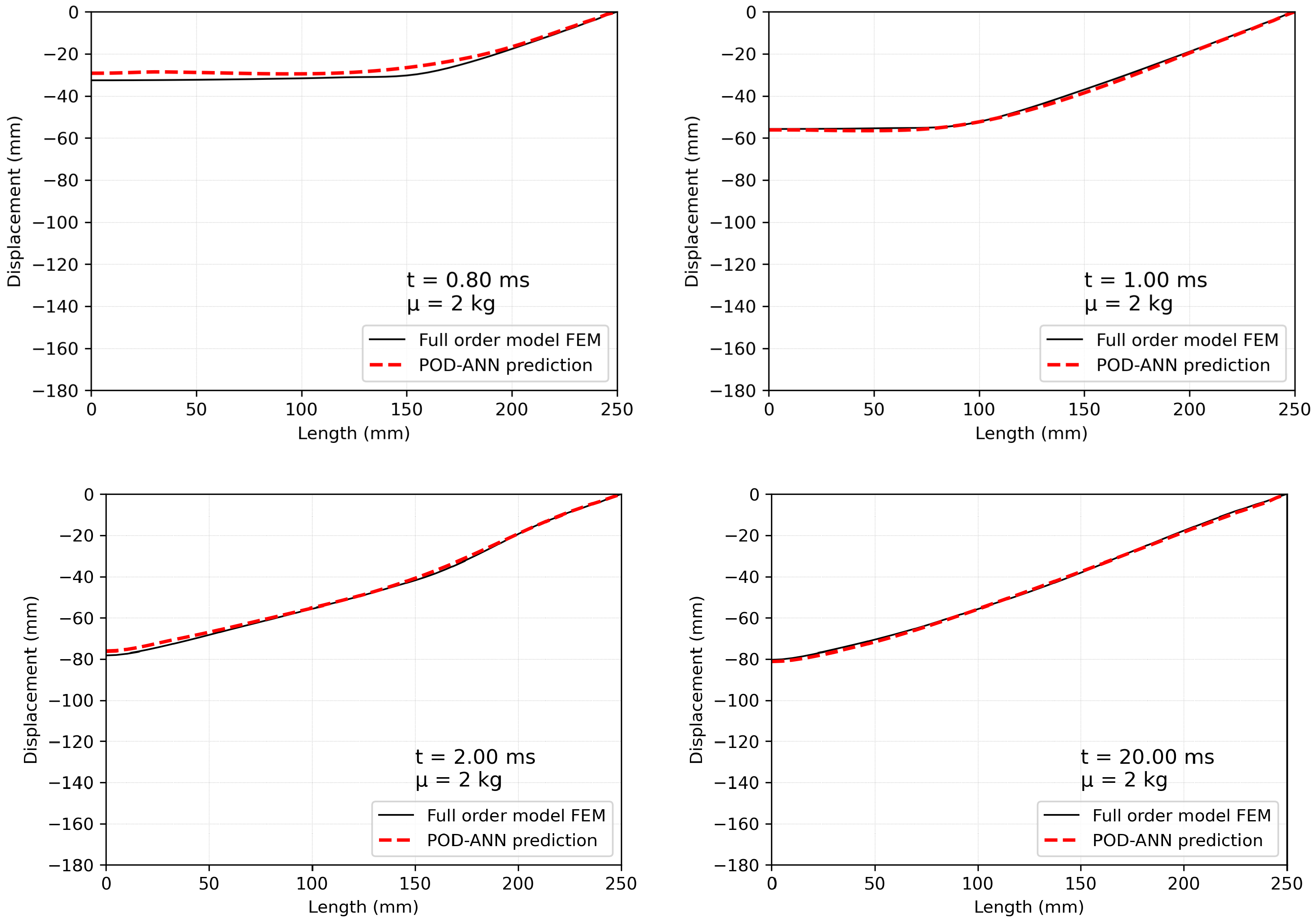

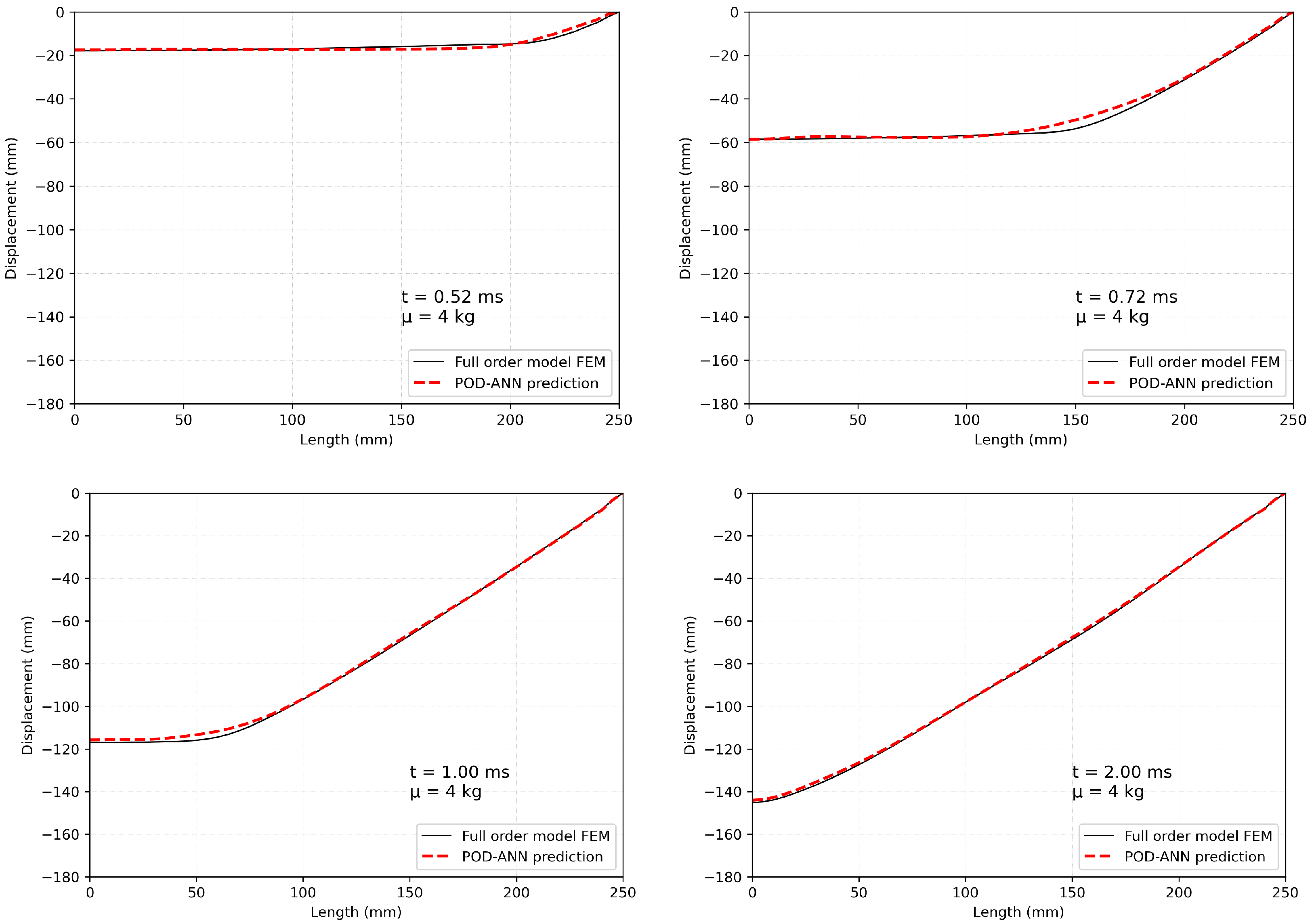

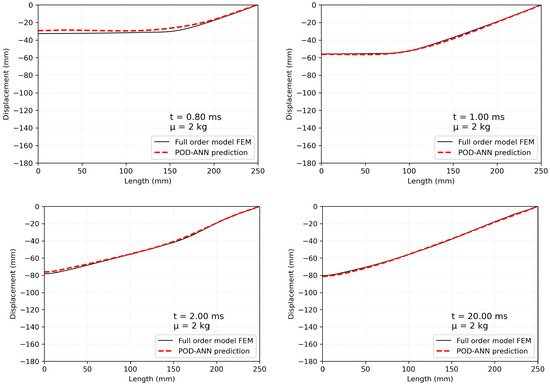

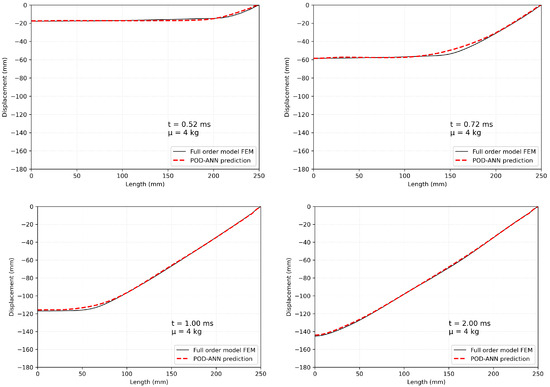

Once the ANN is trained, ROM will be ready to use. Two meaningful cases are considered to show the method’s capability. The mass is 2 kg in the first case, and it is set to 4 kg in the second case. Different time steps in Figure 9 and Figure 10 represent the trend of the displacement field for both the FOM and the ROM with a good agreement. The reduced model can capture both the initial transient where the deformation starts and the final permanent displacement of the plate once the blast load vanishes.

Figure 9.

Different timeframe of the displacement field of the plate when subjected to an explosion caused by 2 kg of TNT.

Figure 10.

Different timeframe of the displacement field of the plate when subjected to an explosion caused by 4 kg of TNT.

4. Discussion

In summary, the proposed framework successfully reduces the model dimension of the analyzed problem in a non-intrusive manner. A strong agreement between the full-order model (FOM) and the reduced-order model (ROM) is observed, as illustrated by the comparison between the representations shown in Figure 5 and Figure 11. The former represents a high-fidelity solution, while the latter is based on a combination of only the first five modes. As a result, the ROM lacks higher-frequency modes, accounting for the plate’s localized dynamics. It is important to note that the plot in Figure 11 is just a linear combination of these five modes, where the combination coefficients are determined through neural network regression. The original problem comprises 51 local basis functions, i.e., the shape functions associated with each finite element node. In contrast, the reduced model replaces these general-purpose local basis functions with a set of global basis functions. Although fewer in number, these global bases are more complex and problem-specific, thus requiring fewer degrees of freedom while effectively capturing the dominant behavior of the system under study.

Figure 11.

Displacement vs. time of the midpoint for several values of TNT mass for the reduced-order model.

The main discrepancies between the two models occur in the initial transient regime, where the ROM curve slightly deviates from the FOM. However, once the initial dynamic effects have terminated, the permanent plastic deformation of the plate is captured with an error of less than 1% across all reported cases and for all parameters within the design space considered for the TNT charge. The main advantage of the ROM solution is the computational time. Given the same hardware, the CPU time of the FOM is around 100 ms, while the time needed for the ROM to compute the same scenario is 3.27 ms. Despite the simplicity of the case study, it can be inferred that reduced-order methods can be satisfactorily employed for highly nonlinear problems, such as those involving blast loads. Additionally, although the presented scenario does not require these methods, the reduction of approximately 97% in computation time highlights the effectiveness of the ROM technique. Hence, this work’s natural evolution corresponds to applying the framework to scenarios of greater complexity and, particularly, of greater computational burden regarding FOM.

5. Conclusions

This work exemplifies the application of model order reduction through POD and a fully connected neural network combined in an approach called POD-NN. Starting from an example of extreme loading conditions on a structure, such as a blast-loaded steel plate, a POD analysis is performed to find the dominant modes that carry the larger amount of information about the physics underlying the problem. A few modes are selected because they are representative of the phenomenon. This enables a reduction by one order of magnitude in the DOFs when transitioning from the full-order model, solved using a classical numerical scheme like finite elements, to the reduced-order model, which relies on just a few basis functions. Then, a supervised machine learning algorithm is trained to find a nonlinear map, which describes the dependency between the parameters and the solution in the reduced space. The ensemble of projection matrix , found via POD, and the nonlinear map , approximated by a neural network, make possible the model order reduction of the system under analysis. Once the neural network is trained, new and never-used parameters in the FOM are queried to obtain the system’s response in a never-computed case at the limited cost of the ROM. Indeed, the numerical method is effective, and its performance allows for a two-order-of-magnitude reduction in computational time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S., G.M., L.L. and A.M.; methodology, E.S., G.M. and L.L.; software, E.S., G.M. and L.L.; validation, E.S. and L.L.; formal analysis, E.S., G.M. and L.L.; investigation, E.S., G.M. and L.L.; resources, E.S. and G.M.; data curation, E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.; writing—review and editing, E.S., G.M., L.L. and A.M.; visualization, E.S.; supervision, M.G. and A.M.; project administration, M.G. and A.M.; funding acquisition, M.G. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CONWEP | Conventional Weapon |

| DOF | Degree Of Freedom |

| FOM | full-order model |

| MOR | model order reduction |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| PDE | partial differential equation |

| POD | Principal Orthogonal Decomposition |

| ROM | reduced-order model |

| SVD | Singular Value Decomposition |

References

- Quarteroni, A.M.; Manzoni, A.; Negri, F. Reduced Basis Methods for Partial Differential Equations: An Introduction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Benner, P.; Gugercin, S.; Willcox, K.E. A Survey of Projection-Based Model Reduction Methods for Parametric Dynamical Systems. SIAM Rev. 2015, 57, 483–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesthaven, J.S.; Ubbiali, S. Non-intrusive reduced order modeling of nonlinear problems using neural networks. J. Comput. Phys. 2018, 363, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, D.W. Microcomputer Programs CONWEP and FUNPRO, Applications of TM 5-855-1, ‘Fundamentals of Protective Design for Conventional Weapons’ (User’s Guide); US Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station: Vicksburg, MS, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp. Abaqus 2023 Documentation. Dassault Systèmes. 2023. Available online: https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/abaqus (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Johnson, G.R. A constitutive model and data for metals subjected to large strains, high strain rates and high temperatures. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Ballistics, Hague, The Netherlands, 19–21 April 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Børvik, T.; Dey, S.; Clausen, A.H. Perforation resistance of five different high-strength steel plates subjected to small-arms projectiles. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2009, 36, 948–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, C.; Lesjak, M.; Bach, C.; Duddeck, F. Data-driven models for crashworthiness optimisation: Intrusive and non-intrusive model order reduction techniques. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2022, 65, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, N.R. dlroms—A Package for Constructing Deep Learning Based Reduced Order Models (DL-ROMs). 2023. Available online: https://github.com/NicolaRFranco/dlrom/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).