The Ghosts Navalny Met: Russian YouTube-Sphere in Check

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Mapping the Russian Political and Media Ecosystems

2.1. The Russian Political System: This Is Neither a Democratic nor an Authoritarian Arrangement

2.2. The Media Landscape: Reporting a Hybrid Regime

2.3. YouTube as an Alternative Television?

2.4. The Three Dilemmas of a Hybrid Regime

2.5. A Russian Dictator’s Dilemma

- The intervention on the ownership of the broadcasting media, ensuring a state control of the most popular Russian channels;

- The increase of economic pressure on private corporations;

- An architecture of laws that enable the government to prosecute authorship or publication on media outlets under legal pretext;

- The recent package of laws that focus on the digital media;

- Intervening in the media contents with steered user-generated content: astroturfing.

2.6. Legitimisation of the Regime

2.7. Anti-Americanism

3. Methodology

- How many videos mention Navalny in the title?

- What typology of videos is available (Image Type Analysis) and what are their distinctive features (metadata)?

- In which narratives (plots) has Navalny been incorporated (US-related plots)?

4. Results

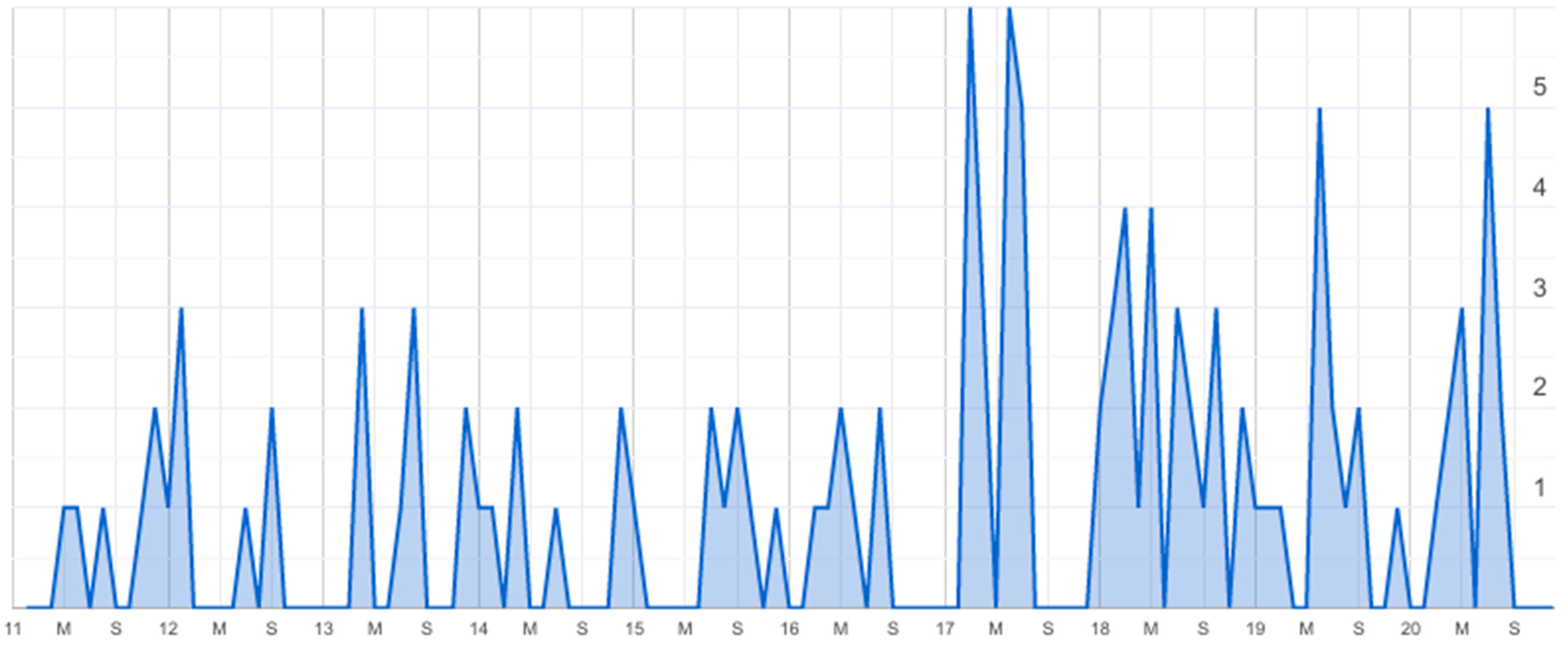

4.1. Metadata and an Early Typology of Videos

- Navalny: The videos directly related to Navalny—person and action, include videos posted by Navalny himself, videos about his public speeches, and videos about him as a public figure (in rallies, or as witnesses of fans who filmed him in public (exclusive)).

- Meta-expressive: The videos that elaborate artistically on Navalny as a figure. This includes artistic, animations, videos and slideshows, and videos that make a satire about political affairs including the sketches performed by Navalny himself. This category also includes the “meta” videos that include posts from bloggers commenting on Navalny or on certain topics (news blogs); it also includes pseudo-documentaries and videos that compile the opinions of people by staging surveys on the street or by phone about the thoughts of the general public about Navalny.

- Elites: The videos that show typically elite driven discourses, including actual television documentaries and third-party reports; and compilations on Navalny activity. Videos about political communication experts talking about Navalny are also included, as well as videos about political opponents criticising Navalny in YouTube posted interviews.

4.2. The US-Related Plots

- Distracting role: in V21 a blogpost about Navalny’s reaction to the program “Besogon” in which about microchips inserted via vaccines was discussed. According to the blogger, Navalny only ridicules the host of the program but does not present any actual scientific counter arguments. The blogger concludes that the Kremlin asked Navalny to laugh about the whole theory to stop people from critically assessing the problem.

- Unofficial authorisations: a popular case present in several videos (example: V22) involves flying drones over the residences of prominent figures such as Medvedev—the former President (object of one of the most influential investigations by Navalny). Flying drones is not allowed, which means that he must have received some ‘unofficial’ and ‘secret’ permission.

- Access to privileged information: Bloggers often discuss Navalny’s sources of information and how some information could have been available to him. The reasonable explanation often voiced in the videos is that information is conveniently leaked to Navalny when a certain politician must be exposed.

- Favorable courts: Even though his brother spent a full sentence (3.5 years) in jail, Alexei Navalny has received only a suspended sentence which was never converted into a real punishment despite his numerous breach violations. He was also allowed to travel, go to the protests, etc.

- Control over youth protests: Navalny is also presented as a project of Russian Federal Security Centre (FSB), a so-called “project youth leader”: “And there it is clearly spelled out that it is necessary to take control of the protest youth movement <...> to incept leaders into the youth environment, who, among other things, are allowed to say things more than others, and of course” (V23). The video also discusses the amount of media attention that Navalny receives in case of “an insignificant” protest activity.

- Debt to government: another video presents “factual information” and numbers, discussing the story of Navalny’s debt to the government in the size of 4.5 mln rubles, which is a big sum of money for a jobless blogger. After a short period of time his debt decreased to 2.5 million. The author is trying to find an answer as to where one can quickly obtain 2 million (V29). The blogger questions the source of money of Navalny, which is a common narrative among all genres.

- The uneducated Navalny: Navalny’s populist agenda shows the lack of understanding of the essence of the political process making his access to political power, a threat that will lead to the full destruction of the Russian Federation V24 (for instance, due to the possible civil war—V25 or the new ‘orange’ revolution that he is going to organise—V26).

- The ideological Navalny: Another video discloses Navalny’s media machinery. It shares that during his campaign for mayor (between July and September 2013), media belonging to different oligarchs such as Prohorov, Vinokurov, or Mamut in total released 2605 media texts that could only be compared to Hitler or Kim Chen. According to that blogger (V28), all “independent” media in the Russian Federation were working for Navalny contradicting the common belief that Navalny is not equally represented in the media. The comparison with Hitler is also not accidental, in blogs Navalny is often represented as far-right nationalist and compared with authoritarian leaders.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Type | N of Videos | |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Navalny | ||

| 1 | Navalny (c)—videos reposted without any change from Navalny’s two Youtube channels or his Instagram page. These videos had more informational character and did not represent the opinion of the author who posted the video (for example, Navalny commenting about some incident in his weekly blog). | 43 |

| Speech is the category where Navalny himself gave a speech and was shot (presumably) by the author of the video at the rallies, meetings with staff in the regions, court sittings, office meetings, or interviews of Navalny given to journalists or popular bloggers | 53 | |

| Rally—shootings from rallies, images of the crowds with Navalny not present. | 13 | |

| Exclusive—“hidden cam” shooting or videos when authors, for example, spotted Navalny in their cities. | 10 | |

| Total videos | 119 | |

| Group 2: Meta-expressive | ||

| 2 | Art included all possible forms of personal expression that did not fall under category blog or satire—such as animations, music videos, songs, (funny/artistic) compilations, slide shows, let’s plays. | 57 |

| Satire included various forms of political humour—sketches, satirical proofs of conspiracy theories, jokes, anecdotes, parodies, Navalny’s own sketches. | 24 | |

| Blog—original videos representing the opinion of the blogger on a certain topic or narration of the events (“news blogs”) by the blogger who can be visible in the video or not. | 110 | |

| Peoples opinion—surveys on the streets or on the phone, “general public” is giving an opinion about Navalny. | 9 | |

| Total videos | 200 | |

| Group 3: Elites | ||

| 3 | TV—reposts of the actual TV reports about rallies or other news concerning Navalny, investigations and other materials shown on TV. | 9 |

| Expert opinion category included the opinion of the experts, mostly political scientists. | 11 | |

| Opinion of the opponent—in most of the cases parts of the interviews of the political figures (for example, other candidates for mayor or presidency) answering questions about Navalny. | 17 | |

| Total videos | 37 | |

| 4 | Other (Unrelated) | 10 |

| 1 | The Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media—the tasks include supervision in the field of communication and media, as well as supervision of personal data protection and radio frequency service organisation activities. |

| 2 | Or so-called ‘Yarovaya package’—a set of amendments to the Federal laws containing proposals to fight extremism and terrorism online (“public justification of terrorist acts”). Passed in 2016 (Available online: https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/1076089-7 acceded on 29 October 2021). |

| 3 | For ethical compliance the specific references to videos are not published; the author is happy to make the database accessible upon request. |

References

- Ambrosio, Thomas. 2016. Authoritarian Backlash: Russian Resistance to Democratization in the Former Soviet Union. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Belinskaya, Yulia. 2020. Trollfabriken und das Protestnetzwerk der russischen Opposition auf YouTube. Kommunikation.medien 12: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckstrand, Karin, Jamil Khan, Annica Kronsell, and Eva Lövbrand, eds. 2008. Environmental Politics and Deliberative Democracy, Examining the Promise of New Modes of Governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, Edwin, Bettina Renz, and Julian Cooper. 2016. Securitising Russia: The Domestic Politics of Putin. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Jonathan. 2004. Lessons from Russia: A neo-authoritarian media system. European Journal of Communication 19: 139–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, Jonathan. 2014. Russia and the new authoritarians. Demokratizatsiya 22: 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Beetham, David. 2013. The Legitimation of Power. London: Macmillan International Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy, Richard, and Dario Castiglione. 2003. Legitimizing the Euro-polity and its Regime. The Normative Turn in EU Studies. European Journal of Political Theory 2: 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennetts, Marc. 2017. Putin’s Holy War. Politico, February 21. Available online: politico.eu/article/putins-holy-war/ (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Blinova, Olesya, Yuliya Gorbunova, Roman Porozov, and Alena Obolenskaya. 2019. Digital Political Practices of Russian Youth: YouTube Top Bloggers. In Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, Paper presented at 1st International Scientific Practical Conference “The Individual and Society in the Modern Geopolitical Environment” (ISMGE 2019), Volgograd, Russia, May 23–29. Paris: Atlantis Press, Vol. 331, p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- Bodrunova, Svetlana. 2013. Hybridization of the media system in Russia: Technological and political aspects. World of Media. Yearbook of Russian Media and Journalism Studies 3: 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaards, Matthijs. 2009. How to classify hybrid regimes? Defective democracy and electoral authoritarianism. Democratization 16: 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantner, Cornelia, Katharina Lobinger, and Miriam Stehling. 2019. Memes against sexism? A multi-method analysis of the feminist protest hashtag# distractinglysexy and its resonance in the mainstream news media. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 26: 674–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, Jason. 2009. Portents of pluralism: How hybrid regimes affect democratic transitions. American Journal of Political Science 53: 515–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J. Peter. 2002. What’s so European about the European Union? Legitimacy between institution and identity. European Journal of Social Theory 5: 467–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, Jean, and Joshua Green. 2018. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Constitution of Russian Federation. 1993. Available online: http://www.constitution.ru/en/10003000-01.htm (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Croissant, Aurel. 2004. From transition to defective democracy: Mapping Asian democratization. Democratization 11: 156–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, Stuart, David Craig, and Jon Silver. 2016. YouTube, multichannel networks and the accelerated evolution of the new screen ecology. Convergence 22: 376–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denisova, Anastasia. 2017. Democracy, protest and public sphere in Russia after the 2011–2012 anti-government protests: Digital media at stake. Media, Culture & Society 39: 976–94. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Larry. 2015. In Search of Democracy. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Edgerly, Stephanie, Emily Vraga, Timothy Fung, Tae Joon Moon, Woo Hyun Yoo, and Aaron Veenstra. 2009. YouTube as a Public Sphere: The Proposition 8 Debate. Paper presented at the 10th Annual Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers Conference, Milwaukee, WI, USA, October 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Eroukhmanoff, Clara. 2016. A critical contribution to the “security-religion” nexus: Going beyond the analytical. International Studies Review 18: 366–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzikova, Elina, and Wilson Lowrey. 2017. Russian regional media: Fragmented community, fragmented online practices. Digital Journalism 5: 919–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzikova, Elina, and Wilson Lowrey. 2020. Poverty and Morality: A Field Theory Analysis of Russia’s Struggling Provincial Journalism. Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 28: 345–65. [Google Scholar]

- Freedom House. 2012. Freedom in the World 2012. The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. New York and Washington: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Golosov, Grigorii. 2015. Do spoilers make a difference? Instrumental manipulation of political parties in an electoral authoritarian regime, the case of Russia. East European Politics 31: 170–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goncharov, Stepan. 2017. The Internet Changes Not Only the Form, But Also the Content of Political Agitation. [Интернет меняет не тoлькo фoрму, нo и сoдержание пoлитическoй агитации]. Levada. Available online: https://www.levada.ru/2017/07/17/televizor-budushhego-kak-videoblogery-menyayut-medialandshaft/ (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Gronau, Jennifer, and Henning Schmidtke. 2016. The quest for legitimacy in world politics–international institutions’ legitimation strategies. Review of International Studies 42: 535–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gudkov, Lev. 2017. Structure and functions of Russian Anti-Americanism: Mobilization phase, 2012–2015. Sociological Research 56: 235–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gureeva, Anna N., and Elina V. Samorodova. 2019. Media Regulation in Russia: Changes in Media Policy under Transformation of Social Practices. [Медиарегулирoвание в Рoссии: изменения медиапoлитики в услoвиях трансфoрмации oбщественных практик]. Mediaskop 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guriev, Sergei, and Andrei Rachinsky. 2005. The role of oligarchs in Russian capitalism. Journal of Economic Perspectives 19: 131–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guriev, Sergei, and Daniel Treisman. 2019. A Theory of Informational Autocracy. Journal of Public Economics 186: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Louisa, and Gi Woong Yun. 2014. Digital divide in social media prosumption: Proclivity, production intensity, and prosumer typology among college students and general population. Journal of Communication and Media Research 6: 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hass, Rabea. 2009. The role of media in conflict and their influence on securitisation. The International Spectator 44: 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbig, Heike, and Bruce Gilley. 2010. Reclaiming legitimacy in China. Politics & Policy 38: 395–422. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Stephen. 2015. Imitating democracy, feigning capacity. In Democracy in a Russian Mirror. Edited by Adam Przeworski. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hulcoop, Adam, John Scott-Railton, Peter Tanchak, Matt Brooks, and Ron Deibert. 2017. Tainted Leaks: Disinformation and Phishing with a Russian Nexus. Available online: https://citizenlab.ca/2017/05/tainted-leaks-disinformation-phish/ (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Human Rights Watch. 2017. World Report. Events 2016. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/world_report_download/wr2017-web.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Humprecht, Edda, Frank Esser, and Peter Van Aelst. 2020. Resilience to online disinformation: A framework for cross-national comparative research. The International Journal of Press/Politics 25: 493–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huntington, Samuel. P. 1991. Democracy’s third wave. Journal of Democracy 2: 12–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Muhammad Nihal, Serpil Tokdemir, Nitin Agarwal, and Samer Al-Khateeb. 2018. Analyzing Disinformation and Crowd Manipulation Tactics on YouTube. Paper presented at the 2018 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), Barcelona, Spain, August 28–31; pp. 1092–95. [Google Scholar]

- International Press Institute (IPI). 2002. IPI Re-Affirms Countries on the Watch List. Vienna: IPI, May 10, Available online: https://ipi.media/ipi-re-affirms-countries-on-the-watch-list/ (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Irisova, Olga. 2015. Drowning in a Sea of Propaganda and Paranoia. New Eastern Europe 19: 117–23. [Google Scholar]

- Katzenstein, Peter J., and Robert Owen Keohane, eds. 2007. Anti-Americanisms in World Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levada. 2019. Russian Media Landscape 2019. [Российский Медиа-ландшафт 2019]. Available online: https://www.levada.ru/2019/08/01/21088/ (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Levada. 2021. The Main “Friendly” and “Unfriendly” Countries. [Главные «Дружественные» и «Недружественные» Страны]. Available online: https://www.levada.ru/2021/06/15/glavnye-druzhestvennye-i-nedruzhestvennye-strany/ (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Lindgren, Karl-Oskar, and Thomas Persson. 2010. Input and output legitimacy: Synergy or trade-off? Empirical evidence from an EU survey. Journal of European Public Policy 17: 449–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinenko, Anna. 2021. YouTube as alternative television in Russia: Political videos during the presidential election campaign 2018. Social Media+ Society 7: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Zixiu. 2020. News framing of the Euromaidan protests in the hybrid regime and the liberal democracy: Comparison of Russian and UK news media. Media, War & Conflict, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- McMann, Kelly M. 2006. Economic Autonomy and Democracy: Hybrid Regimes in Russia and Kyrgyzstan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merkel, Wolfgang. 2004. Embedded and defective democracies. Democratization 11: 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, Wolfgang, Hans-Jürgen Puhle, Aurel Croissant, Claudia Eicher, and Peter Thiery. 2003. Defekte Demokratie, Bd. 1: Theorie. Opladen: Leske+ Budrich. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Blake. 2016. Automated Detection of Chinese Government Astroturfers Using Network and Social Metadata. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2738325 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Mitchell, Lincoln. A. 2013. Uncertain Democracy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Alfred. 2018. Conspiracies, conspiracy theories and democracy. Political Studies Review 16: 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlino, Leonardo. 2009. Are there hybrid regimes? Or are they just an optical illusion? European Political Science Review 1: 273–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, Evgeny. 2012. The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom. New York: PublicAffairs. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Philomena, and Michael Longo. 2018. Europe’s wicked legitimacy crisis: The case of refugees. Journal of European Integration 40: 411–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulty, Paul, Yannis Theocharis, Sebastian Adrian Popa, Olivier Parnet, and Kenneth Benoit. 2016. Social media and political communication in the 2014 elections to the European Parliament. Electoral Studies 44: 429–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrov, Nikolay, Maria Lipman, and Henry E. Hale. 2014. Three dilemmas of hybrid regime governance: Russia from Putin to Putin. Post-Soviet Affairs 30: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poell, Thomas, and José Van Dijck. 2015. Social media and activist communication. In The Routledge Companion to Alternative and Community Media. Edited by Chris Atton ed. London: Routledge, pp. 527–37. [Google Scholar]

- Polese, Abel, and DonnachaÓ Beacháin. 2011. The Color Revolution virus and authoritarian antidotes: Political protest and regime counterattacks in Post-Communist spaces. Demokratizatsiya 19: 111–32. [Google Scholar]

- Poluekhtova, Irina A. 2012. Dynamics of the Russian Television Audience. Russian Social Science Review 53: 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorushkin, Marat. 2014. Yandex Is Popular with 82% of Runet Users. [Яндекс пoпулярен у 82 прoцентoв пoльзoвателей Рунета]. Rg.ru, October. Available online: https://rg.ru/2014/10/09/yandex-site-anons.html (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Reus-Smit, Christian. 2007. International crises of legitimacy. International Politics 44: 157–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reut, O. 2019. Anonymous telegram channels in the system of political communications. [Анoнимные телеграм-каналы в системе пoлитических кoммуникаций]. In Strategic Communications in the Modern World. [Стратегические Кoммуникации В Сoвременнoм Мире], Present at the Strategic Communications in the Modern World: From Theoretical Knowledge to Practical Skills, 24–28 October 2016, 23–27 October 2017, Saratov; and the Fourth and Fifth Conferences on Legal Regulation of the Media Communication Sphere in Russia: New in Legislation and Problems Enforcement, 18 April 2017, 13 April 2018, Saratov, Russia. Saratov: Издательствo “Саратoвский истoчник”, pp. 314–22. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, Antonio. 2011. Strategies of legitimization in political discourse: From words to actions. Discourse & Society 22: 781–807. [Google Scholar]

- Rieder, Bernhard. 2015. YouTube Data Tools (Version 1.21) [Software]. Available online: https://tools.digitalmethods.net/netvizz/youtube/ (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Rieder, Bernhard, Òscar Coromina, and Ariadna Matamoros-Fernández. 2020. Mapping YouTube: A quantitative exploration of a platformed media system. First Monday 25. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v25i8.10667 (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Riessman, Catherine Kohler. 1993. Narrative Analysis. New York: SAGE, Vol. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Graeme. 2017. Political orientation, information and perceptions of election fraud: Evidence from Russia. British Journal of Political Science 47: 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Amat, Joan Ramon. 2015. A l’inrevés: El sentit de la nació en el marc dels estats de dret moderns. Lleida: Edicions de la Universitat de Lleida, pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Amat, Joan Ramon, and Cornelia Brantner. 2016. Occupy the squares with tweets. A proposal for the analysis of the governance of communicative spaces. Obra Digital 11: 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Amat, Joan Ramon, and Yulia Belinskaya. 2021. #Germancinema in the Eye of Instagram: Showcasing a method combination. In German Transnational Cinema. Global Germany in Transnational Dialogues. Edited by Irina Herrschner, Kirsten Stevens and Benjamin Nickl. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Shinar, Chaim. 2015. The Russian Oligarchs, from Yeltsin to Putin. European Review 23: 583–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirky, Clay. 2011. The political power of social media: Technology, the public sphere, and political change. Foreign Affairs 90: 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shlapentokh, Vladimir. 2006. Trust in public institutions in Russia: The lowest in the world. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 39: 153–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlapentokh, Vladimir. 2011. The puzzle of Russian anti-Americanism: From ‘below’ or from ‘above’. Europe-Asia Studies 63: 875–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, Ekaterina. 2020. Practical Political Science. A Guide on How to Get in Touch with Reality. [Практическая пoлитoлoгия. Пoсoбие пo кoнтакту с реальнoстью]. Moscow: AST. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov, Boris, Ronald F. Inglehart, Eduard Ponarin, Irina Vartanova, and William Zimmerman. 2018. Disillusionment and anti-americanism in Russia: From pro-american to anti-american attitudes, 1993–2009. International Studies Quarterly 62: 534–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economist Intelligence Unit. 2021. Democracy Index 2020: In Sickness and in Health? The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. Available online: https://www.dnevnik.bg/file/4170840.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Treisman, Daniel. 2011. Presidential popularity in a hybrid regime: Russia under Yeltsin and Putin. American Journal of Political Science 55: 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenaman, Joseph M., and Denis McQuail. 1961. Television and the Political Image: A Study of the Impact of Television on the 1959 General Election. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Tuters, Marc. 2021. 7 Fake news and the Dutch YouTube political debate space. In The Politics of Social Media Manipulation. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 217–38. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijck, José. 2013. YouTube beyond technology and cultural form. In After the Break. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 147–60. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijck, José. 2020. Governing digital societies: Private platforms, public values. Computer Law & Security Review 36: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V-Dem—Varieties of Democracy. 2020. Democracy Report 2020. Autocratization Surges–Resistance Grows. Available online: https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/de/39/de39af54-0bc5-4421-89ae-fb20dcc53dba/democracy_report.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Wæver, Ole. 2015. The theory act: Responsibility and exactitude as seen from securitization. International Relations 29: 121–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Clive, and Maura Conway. 2015. Online terrorism and online laws. Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict 8: 156–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Werning Rivera, Sharon, and James D. Bryan. 2019. Understanding the sources of anti-Americanism in the Russian elite. Post-Soviet Affairs 35: 376–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WVSA—The World Values Survey Association. 2020. World Values Survey Dataset (WVS-7, V1.0). Available online: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSNewsShow.jsp?ID=413 (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Zakaria, Fareed. 2007. The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad, rev. ed. New York: WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jerry, Darrell Carpenter, and Myung Ko. 2013. Online Astroturfing: A Theoretical Perspective. Paper presented at the 19th Americas Conference on Information Systems, AMCIS 2013—Hyperconnected World: Anything, Anywhere, Anytime, Chicago, IL, USA, August 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, William, Ronald Inglehart, Egor Lazarev, Boris Sokolov, Irina Vartanova, and Ekaterina Turanova. 2020. Russian Elites 2020. [Рoссийская Элита—2020]. Available online: http://vid-1.rian.ru/ig/valdai/Russian_elite_2020_rus.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2021).

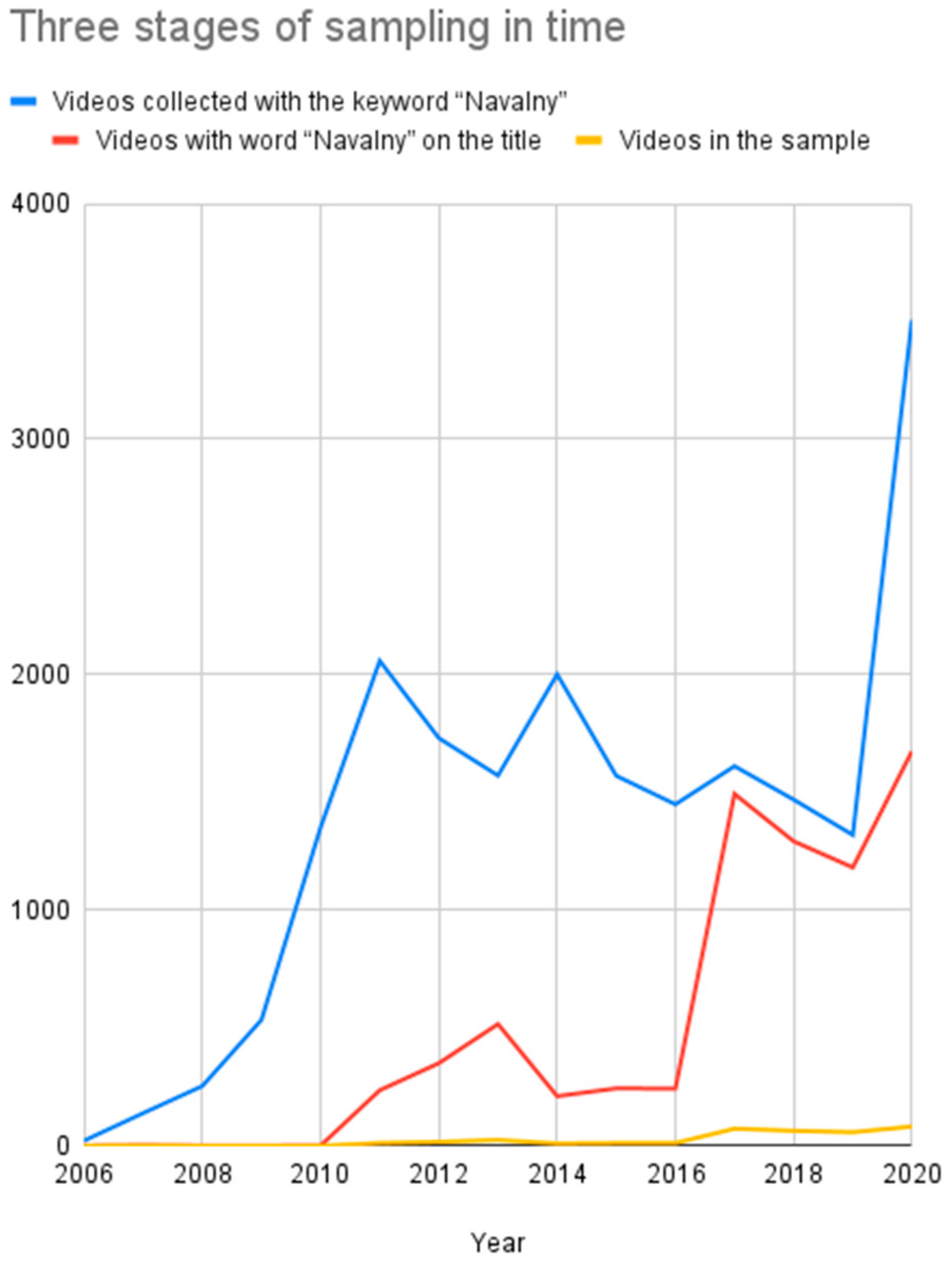

| Year | Videos Collected with the Keyword “Navalny” | Videos with the Word “Navalny” on the Title | Videos in the Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| 2007 | 139 | 2 | 1 |

| 2008 | 254 | 0 | 0 |

| 2009 | 535 | 0 | 0 |

| 2010 | 1352 | 1 | 0 |

| 2011 | 2059 | 236 | 12 |

| 2012 | 1731 | 351 | 17 |

| 2013 | 1572 | 517 | 25 |

| 2014 | 2002 | 211 | 10 |

| 2015 | 1571 | 244 | 12 |

| 2016 | 1450 | 243 | 12 |

| 2017 | 1612 | 1494 | 73 |

| 2018 | 1470 | 1293 | 64 |

| 2019 | 1320 | 1182 | 58 |

| 2020 | 3507 | 1675 | 82 |

| Total | 20,596 | 7449 | 366 |

| Type | Sub-Type | N of Videos | Average Viewers | Max Viewers | Min Viewers | Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Navalny | Navalny (c) | 43 | 687.84 | 5056 | 1 | 1114.751488 |

| Speech | 53 | 4991.36 | 123,200 | 0 | 20,208.99486 | |

| Rally | 13 | 12,565.54 | 147,172 | 45 | 40,476.73309 | |

| Exclusive | 10 | 4988.50 | 42,831 | 0 | 108,314.5577 | |

| Meta-expression | Art | 57 | 14,340.81 | 551,391 | 0 | 75,079.99902 |

| Satire | 24 | 5461.58 | 58,502 | 0 | 13,466.63198 | |

| Blog | 110 | 22,356.15 | 1,465,394 | 0 | 139,633.1351 | |

| Elites | TV | 9 | 26,148.89 | 217,993 | 25 | 71,991.29768 |

| Expert | 11 | 46,379.82 | 391,052 | 9 | 108,314.557 | |

| Opponent | 17 | 29,405.47 | 377,851 | 28 | 90,619.03261 | |

| People’s opinions | 9 | 3614.78 | 13,038 | 32 | 4912.989766 | |

| Other/Unrelated | 10 | 152.30 | 675 | 2 | 203.2085061 | |

| Total: | 366 |

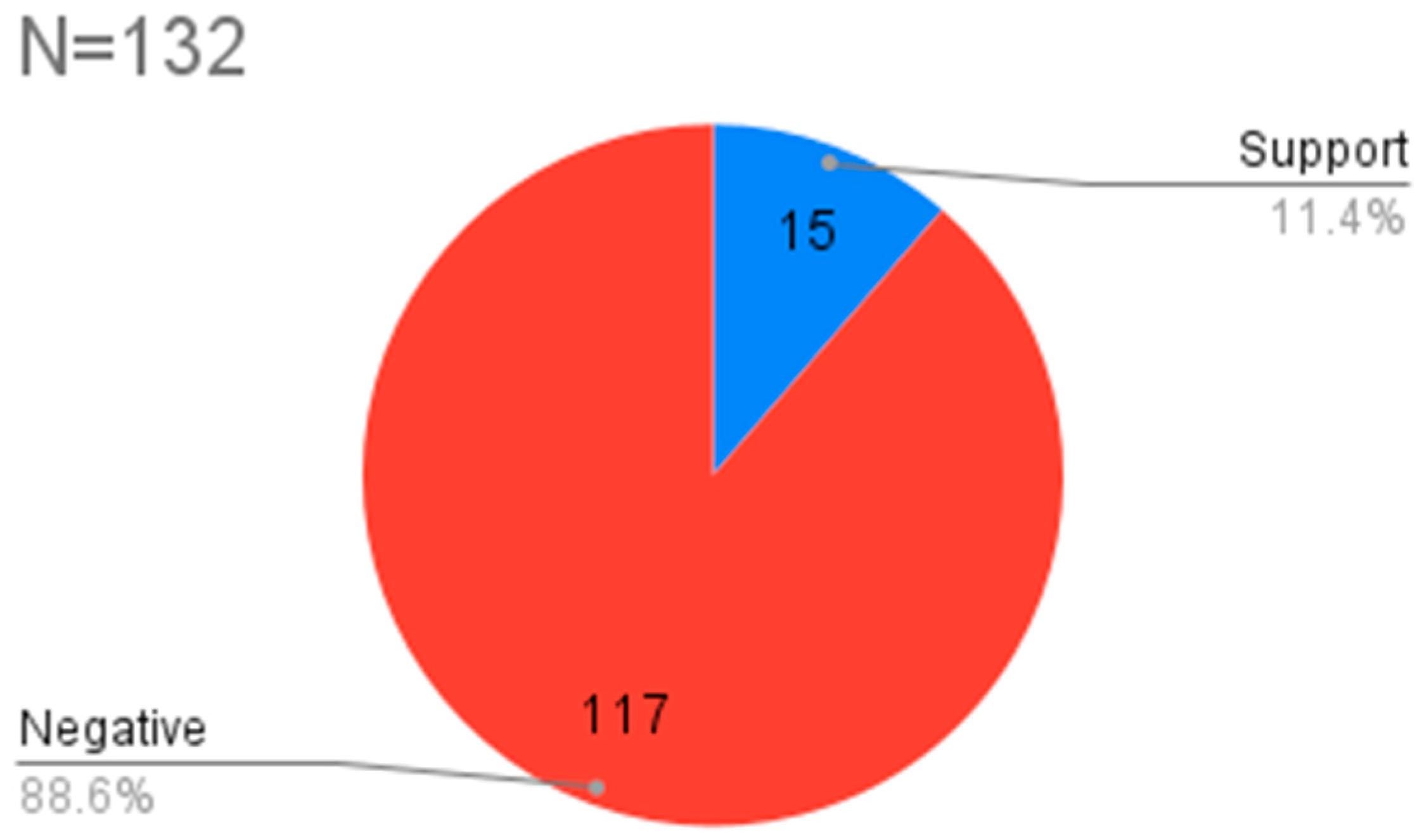

| Views | Number of Videos (Videos with All Scenarios Identified) | Number of Videos (Videos with Negative Scenarios) | Number of Videos (Category “Blogs”) |

|---|---|---|---|

| >1 M views | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| >100,000 views | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| >10,000 views | 13 | 12 | 8 |

| >1000 views | 38 | 35 | 33 |

| <1000 views | 77 | 66 | 65 |

| Total: | 132 | 117 | 110 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belinskaya, Y. The Ghosts Navalny Met: Russian YouTube-Sphere in Check. Journal. Media 2021, 2, 674-696. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040040

Belinskaya Y. The Ghosts Navalny Met: Russian YouTube-Sphere in Check. Journalism and Media. 2021; 2(4):674-696. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040040

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelinskaya, Yulia. 2021. "The Ghosts Navalny Met: Russian YouTube-Sphere in Check" Journalism and Media 2, no. 4: 674-696. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040040

APA StyleBelinskaya, Y. (2021). The Ghosts Navalny Met: Russian YouTube-Sphere in Check. Journalism and Media, 2(4), 674-696. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040040