The Framing of the National Men’s Basketball Team Defeats in the Eurobasket Championships (2007–2017) by the Greek Press

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Successes of Greek National Teams and Media Coverage

1.2. Framing Theory

1.3. The Primary Frames in the Media and the Persuasion Processes

1.4. Sports Journalism and the Effects of Framing

1.5. The Attribution of Responsibility Frame

1.6. Aim of the Study and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method Selection

2.2. Selection of Approach—Research Validity

2.2.1. Material Selection and Recording Procedures

2.2.2. Frame Measurements

2.2.3. Reliability Coding

3. Results

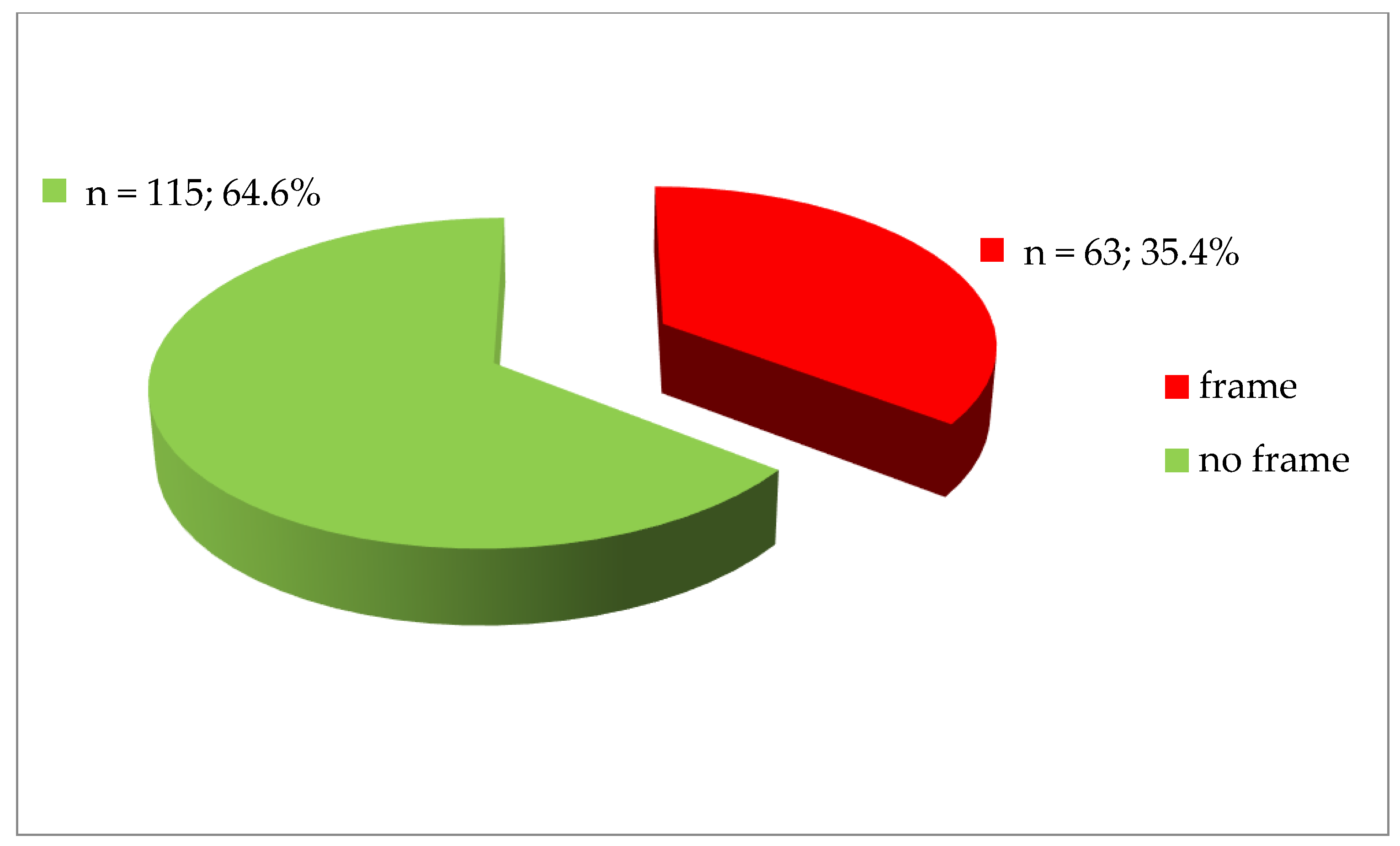

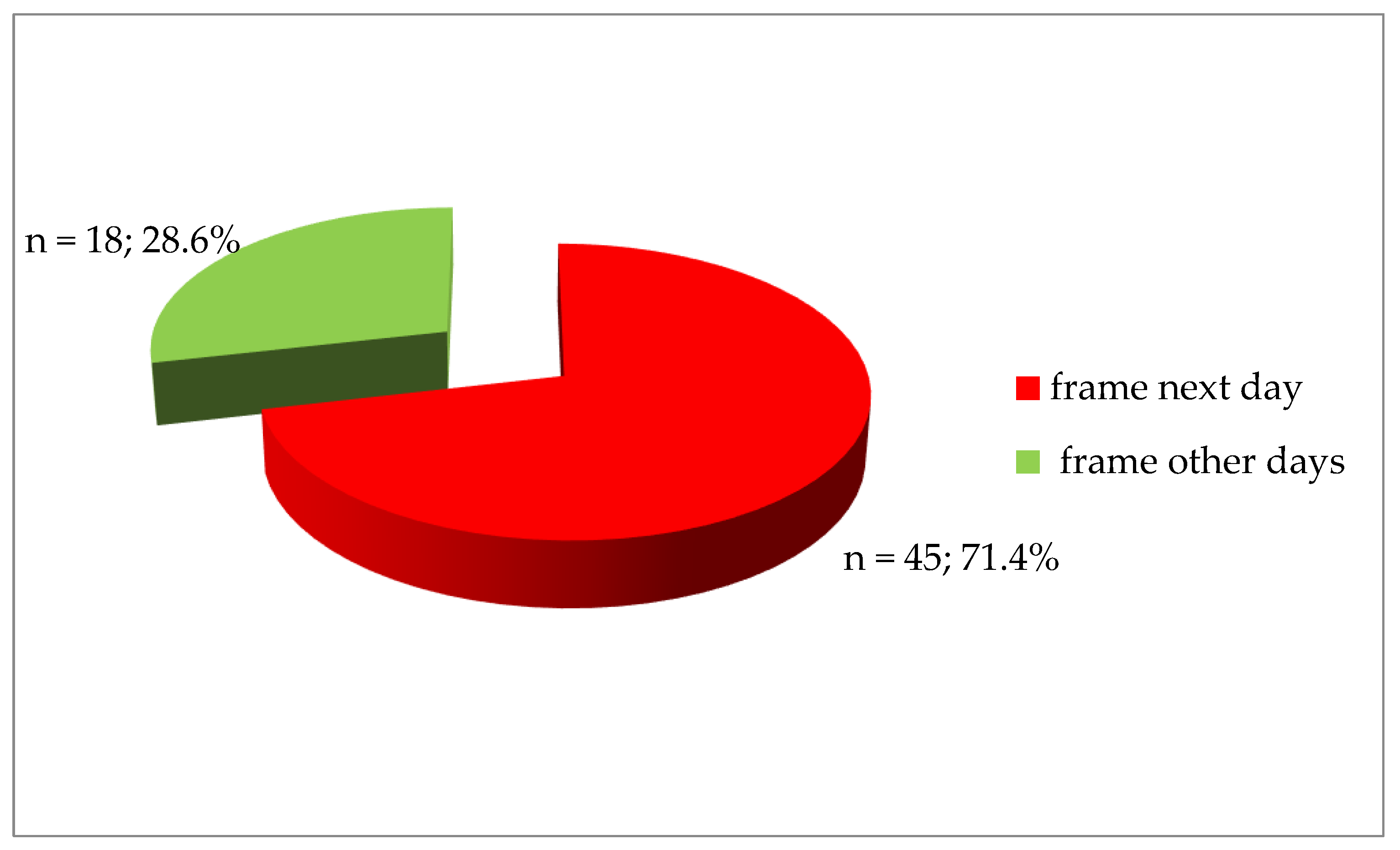

3.1. The Attribution of Responsibility Frame

3.2. The Differences in Framing between the Newspapers

3.3. Defeat Causes Focused on, and Agents and Individuals Blamed by the Media

- (1)

- The players’ weaknesses in the game (METROSPORT 2007a).

- (2)

- The players’ mistakes in the game (METROSPORT 2009b, 2017a).

- (3)

- Τhe fatigue and the loss of strength by the athletes (KATHIMERINI 2017; METROSPORT 2009c; TA NEA 2007a).

- (4)

- The players’ stress (METROSPORT 2013b).

- (5)

- The viruses that afflicted the players (ETHNOS 2007).

- (6)

- The losses of players caused by injuries (METROSPORT 2011).

- (7)

- The athletes’ decision not to participate in the championship (KATHIMERINI 2011).

- (8)

- The lack of:

- Focus of the basketball players in the game (METROSPORT 2013c, 2017c);

- Faith in their abilities by the athletes (METROSPORT 2015);

- Passion in their game (METROSPORT 2017b).

- (9)

- The coaches’ mistakes (ETHNOS 2013; METROSPORT 2007b).

- (10)

- Bad refereeing (METROSPORT 2009a).

- (11)

- Off-field factors, such as:

- The uproar in the stadium (METROSPORT 2007c);

- The bad scheduling of the championship that deprived the players of rest (TA NEA 2007b);

- Even in… superstitions! (METROSPORT 2007d; TA NEA 2015).

- (12)

- The wrong handlings by the Greek Basketball Federation administration members, such as:

- The coach selection (METROSPORT 2013a);

- Other decisions and actions both by its president George Vasilakopoulos1 and by the general secretary Panagiotis Tsagronis2, such as the improper scheduling/bad scheduling (TA NEA 2017).

3.4. Other Frames and the Framing Function

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences in Coverage

4.2. The Focus of the Articles on the Defeat Causes and the Agents and Individuals the Responsibilities Were Linked with

4.3. Other Frames and Framing Functions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | George Vasilakopoulos was the president of the Greek Basketball Federation. |

| 2 | Panagiotis Tsagronis was the General Secretary of the Greek Basketball Federation. |

| 3 | This is the country with the current name Republic of North Macedonia, as the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) was renamed with the Prespa agreement on 12 June 2018, a name which it used in the event studied in this paper. |

| 4 | Giannis Antetokounmpo and Theodoros Papaloukas were basketball players of the Greek National Team in 2009 Eurobasket Championship |

| 5 | Andrea Trinchieri was the National Team coach in the 2013 Eurobasket Championship. |

| 6 |

References

- Alabaster, Jay. 2017. News coverage of taiji’s dolphin hunts: Media framing and the birth of a global prohibition regime. Asian Journal of Journalism and Media Studies 1: 45–73. [Google Scholar]

- Androulakis, Georgios. 1997. Sports terminology and Greek language: Borrowing, comparisons with other European languages, problems, suggestions. Paper present at the 1st Conference on Greek Language and Terminology, Hellenic Society of Terminology, Athens, Greece, October 30–November 1; pp. 337–47. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Androulakis, Goergios. 2008. Researching Greek print sports: Methodological, linguistic and social issues. In The Discourse for Mass Communication. The Greek Example. Edited by Politis Periklis. Thessaloniki: Institute of Modern Greek Studies (Manolis Triandaphyllidis Foundation), pp. 72–111. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Apodytiriakias. 2016. Bravado, His Brother in the National Team. Available online: https://www.apodytiriakias.gr/athlitika/2016/07/08/ntailiki-ton-adelfo-tou-stin-ethniki-o-antetokoumpo.aspx (accessed on 21 March 2022). (In Greek).

- Bairaktaris, Ιoannis. 2014. You Know That…. Available online: https://www.contra.gr/podosfairo/.7178244.html (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Banerjee, Mousumi, Michelle Capozzoli, Laura McSweeney, and Debajyoti Sinha. 1999. Beyond Kappa: A Review of Interrater Agreement Measures. Canadian Journal of Statistics 27: 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerman, Max H. 1984. The Relevance of Kahneman and Tversky’s Concept of Framing to Organizational Behavior. Journal of Management 10: 333–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, Travis R., and Karen L. Hartman. 2018. Stealing Thunder through Social Media: The Framing of Maria Sharapova’s Drug Suspension. International Journal of Sport Communication 11: 369–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourlakis, Nikos. 2019. The End of “Masony” Hurt Basketball 9. Available online: https://www.sportime.gr/bloggers/nikos-mpourlakis/to-telos-tis-masonias-pligose-to-basket/ (accessed on 11 July 2021). (In Greek).

- Bryman, Alan. 2017. Social Research Methods. Athens: Gutenberg. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Cacciatore, Michael A., Dietram A. Scheufele, and Shanto Iyengar. 2016. The End of Framing as We Know It and the Future of Media Effects. Mass Communication and Society 19: 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaj, Lindita. 2010. Media Framing through Stages of a Political Discourse: International News Agencies’ Coverage of Kosovo’s Status Negotiations. International Communication Gazette 72: 635–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcary, Marion. 2009. The Research Audit Trial—Enhancing Trustworthiness in Qualitative Inquiry. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 7: 635–53. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, Meaghan K., and Daniel S. Mason. 2016. Damage Control: Media Framing of Sport Event Crises and the Response Strategies of Organizers. Event Management 20: 119–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassino, Daniel. 2007. Entman, Robert M. Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion, and U.S. Foreign Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. Journal of Conflict Studies 27: 128–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1960. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement 20: 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, Daniel Sarver, Cheryl Ann Lambert, David Cassilo, and Zachary Humphries. 2017. Kap takes a knee: A media framing analysis of Colin Kaepernick’s anthem protest. In Looking Back, Looking Forward: 20 Years of Developing Theory & Practice. Paper presented at the 20th International Public Relations Research Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, March 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran, Paul E. 2006. Emotional framing in Australian journalism. Paper presented at the Australian & New Zealand Communication Association International Conference, Adelaide, South Australia, July 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo, Paul. 2017. Framing: Media frames. In The international Encyclopedia of Media Effects. Edited by Patrick Rössler, Cynthia A. Hoffner and Liesbet van Zoonen. New York: Wiley, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo, Paul. 2019. Framing theory and journalism. In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies. Edited by Tim P. Vos and Folker Hanusch. New York: Wiley Blackwell-ICA, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo, Paul, and Donna Shaw. 2018. Journalism as framing. In Handbook of Communication science: Journalism. Edited by Tim P. Vos. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 205–33. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo, Paul, and Jim A. Kuypers. 2010. Doing News Framing Analysis. Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Gavin. 2014. Framing Theory. Available online: https://masscommtheory.com/theory-overviews/framing-theory/ (accessed on 23 April 2018).

- Dimitrova, Daniela V., Lynda Lee Kaid, Andrew Paul Williams, and Kaye D. Trammell. 2005. War on the Web: The immediate news framing of Gulf War II. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 10: 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, Douglas. 2002. Representing gun owners. Frame identification as social responsibility in news media discourse. Written Communication 19: 44–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitriu, Diana-Luiza. 2013. Who is responsible for the team’s results? Media framing of sports actors’ responsibility in major sports competitions. Revista Română de Comunicare şi Relaţii Publice 15: 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunning, Eric, Patrick Murphy, and John Williams. 1986. Spectator violence at football matches: Towards a sociological explanation. The British Journal of Sociology 37: 221–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Shelly Chaiken. 2007. The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Social Cognition 25: 582–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, Peter. 2017. Cheerleaders or critics? Australian and Indian sports journalists in the contemporary age. Digital Journalism 5: 532–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 43: 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, Robert M. 2007. Framing bias: Media in the distribution of power. Journal of Communication 57: 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESIEA. 1979. Statute of the Journalists’ Union of Athens Daily Newspapers. Available online: https://www.esiea.gr/katastatiko (accessed on 21 March 2022). (In Greek).

- ETHNOS. 2005. The “other Greece” SHINED. ETHNOS, September 26. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- ETHNOS. 2007. Our National Team lost in the details. ETHNOS, September 17. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- ETHNOS. 2013. Trinchieri counts days (as a coach). ETHNOS, September 16. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Figgou, Lia. 2020. Agency and accountability in (un) employment-related discourse in the era of “crisis”. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 39: 200–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontpages. 2022. Newspaper Headlines. Sports. Available online: www.frontpages.gr (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Gitlin, Todd. 1980. The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media and the Making an Unmaking of the New Left. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin, Todd. 2003. The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1986. Frame Analysis. Boston: Northeastern University. First published in 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Paul. 1974. Soccer’s tribal wars. New Society 29: 602–4. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Virginia S., and Jan Boehmer. 2020. Sport for Development and Peace: Framing the Global Conversation. Communication & Sport 8: 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HBF. 2021. Great Times. List of the Games in Which Our National Teams Took One of the First Three Places. Available online: https://www.basket.gr/megales-stigmess/ (accessed on 21 March 2022). (In Greek).

- Hearns-Branaman, Jesse Owen. 2020. Using GMG’s news game as a pedagogical tool: Exploring journalism students’ framing practices. Media Practice and Education 21: 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, Juan José, Lifen Cheng, and Carlos Muňiz. 2005. Framing Latin America in the Spanish press: A cooled down friendship between two fraternal lands. Communications 30: 359–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Cartee, Karen S. 2005. News Narratives and News Framing: Constructing Political Reality. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, Michael, and Christer Clerwall. 2018. Transparency to the rescue? Evaluating citizens’ views on transparency tools in journalism. Journalism Studies 19: 1923–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KATHIMERINI. 2011. The National Team achieved its goal and gave future promises. KATHIMERINI, September 20. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- KATHIMERINI. 2017. The National Team had the means but lacked the strength. KATHIMERINI, September 14. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Knight, Myra Gregory. 1999. Getting past the impasse: Framing as a tool for public relations. Public Relations Review 25: 381–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsanti, Maria-Dimitra, and Nikolaos Tsigilis. 2020. Doping incidents in sports: Presentation and coverage in the electronic press. In Sports and Media. Rhetoric, Identities and Representations. Edited by Tsigilis Nikolaos and Diamantis Mastrogiannakis. Thessaloniki: Zygos, pp. 147–75. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Kozman, Claudia. 2017. Measuring issue-specific and generic frames in the media’s coverage of the steroids issue in baseball. Journalism Practice 11: 777–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kreuter, Judith. 2021. Ideas and Objects, Meaning and Causation—Frame Analysis from a Modernist Social Constructivism Perspective. In Climate Engineering as an Instance of Politicization. Edited by Kreuter Judith. Cham: Springer, pp. 73–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lecheler, Sophie, and Claes H. De Vreese. 2019. News Framing Effects. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Nicky, and Andrew J. Weaver. 2015. More than a game: Sports media framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and enjoyment. Communication & Sport 3: 219–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ličen, Simon, and Andrew C. Billings. 2013. Affirming nationality in transnational circumstances: Slovenian coverage of continental franchise sports competitions. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 48: 751–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ličen, Simon, and Mojca Doupona Topič. 2008. The imbalance of commentators’ discourse during a televised basketball match. Kinesiology 40: 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard, Matthew, Jennifer Snyder-Duch, and Cheryl Campanella Bracken. 2002. Content analysis in mass communication: Assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Human Communication Research 28: 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnamara, Jim R. 2005. Media content analysis: Its uses, benefits and best practice methodology. Asia Pacific Public Relations Journal 6: 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Marland, Alex. 2012. Political photography, journalism, and framing in the digital age: The management of visual media by the Prime Minister of Canada. The International Journal of Press/Politics 17: 214–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsiola, Maria, Panagiotis Spiliopoulos, and Nikolaos Tsigilis. 2022. Digital Storytelling in Sports Narrations: Employing Audiovisual Tools in Sport Journalism Higher Education Course. Education Sciences 12: 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, Jörg. 2009. What’s in a frame? A content analysis of media framing studies in the world’s leading communication journals, 1990–2005. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 86: 349–67. [Google Scholar]

- Matthes, Jörg, and Matthias Kohring. 2008. The content analysis of media frames: Toward improving reliability and validity. Journal of communication 58: 258–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, Maxwell E. 2005. A look at agenda-setting: Past, present and future. Journalism Studies 6: 543–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, Maxwell E., and Donald L. Shaw. 1972. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly 36: 176–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, William J. 1986. The vicissitude of attitudes and similar representational constructs in twentieth-century psychology. European Journal of Social Psychology 16: 89–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- METROSPORT. 2007a. One Speed Back. METROSPORT, September 6. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2007b. Soul without a system. METROSPORT, September 17. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2007c. The bet was lost in the details. METROSPORT, September 16. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2007d. The curse of the small final. METROSPORT, September 17. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2009a. Complaints on refereeing. METROSPORT, September 20. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2009b. We did not play well. METROSPORT, September 14. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2009c. Zisis: We had no energy. METROSPORT, September 14. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2011. Amazing atmosphere we fought until the end. METROSPORT, September 18. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2013a. Dry-headed Italian coach. METROSPORT, September 18. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2013b. I have no complaints, the team was stressed. METROSPORT, September 9. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2013c. Trinchieri: We were not mentally strong. METROSPORT, September 10. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2015. We would take it (the game) if we believed it. METROSPORT, September 16. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2017a. Leaky defense. METROSPORT, September 3. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2017b. Τhe ones who play with soul are the ones who should play in our National Team. METROSPORT, September 6. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- METROSPORT. 2017c. We should learn from our mistakes and be more concentrated with Slovenia. METROSPORT, September 3. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Mijatov, Nikola, and Sandra S. Radenović. 2019. (Mis)use of football: Analysis of media reports about matches between Serbia and Croatia in 2013. SPORT: Science & Practice 9: 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mikelonis, Ashley. 2017. Exploring the Success and Defeat of Ronda Rousey: A Content Analysis of Twitter and Newspaper Coverage from 2014–2016. Master’s thesis, School of Journalism, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Thomas E., and Zoe M. Oxley. 1999. Issue framing effects on belief importance and opinion. The Journal of Politics 61: 1040–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Thomas E., Rosalee A. Clawson, and Zoe M. Oxley. 1997. Media framing of a civil liberties conflict and its effect on tolerance. American Political Science Review 91: 567–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, Russell W., Marion R. Just, and Ann N. Crigler. 1992. Common Knowledge. Chicago: Chicago University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newsbeast. 2021. Responsibility and Martins the lost Cup—The First to Leave Olympiakos. Available online: https://www.newsbeast.gr/sports/arthro/7428593/efthyni-kai-martins-to-chameno-kypello-o-protos-pou-fevgei-apo-olybiako (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Pan, Zhongdang, and Gerald M. Kosicki. 1993. Framing analysis: An approach to news discourse. Political Communication 10: 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, Roi. 2013. Greece. In International Sports Press Survey 2011. Quantity and Qulity of Sports Reporting. Edited by Horky Thomas and Jörg-Uwe Nieland. Norderstedt: BoD–Books on Demand, vol. 5, pp. 123–28. [Google Scholar]

- Politis, Periklis. 2001. Oral and written speech. In Encyclopedic Guide to the Language. Edited by Anastasios-Phoivos Christides. Thessaloniki: Center for the Greek Language, pp. 58–62. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Politis, Periklis. 2008. The Language of Television News. The News Bulletins of Greek Television (1980–2010). Thessaloniki: Institute of Modern Greek Studies (Manolis Triandaphyllidis Foundation). (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Price, Vincent, David Tewksbury, and Elizabeth Powers. 1997. Switching trains of thought: The impact of news frames on readers’ cognitive responses. Communication Research 24: 481–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PSAT. 2013. Statute of Greek Sports Journalists Association. Available online: https://psat.gr (accessed on 21 March 2022). (In Greek).

- Ramadan, Fadlan A., and Narayana M. Prastya. 2019. When Media Owning Sports Club: Republika Editorial Policy in News Coverage about Inter Milan and Satria Muda. Asian Journal of Media and Communication (AJMC) 3: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Reese, Stephen D. 2007. The framing project: A bridging model for media research revisited. Journal of Communication 57: 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendon, Hector, Maria de Moya, and Melissa A. Johnson. 2019. “Dreamers” or threat: Bilingual frame building of DACA immigrants. Newspaper Research Journal 40: 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeers, Timothy. 2019. ‘We go green in Beijing’: Situating live television, urban motor sport and environmental sustainability by means of a framing analysis of TV broadcasts of Formula E. Sport in Society 22: 2089–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheufele, Bertram. 2004. Framing effects approach A theoretical and methodological critique. Communications 29: 401–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SDNA. 2021. Boloni’s responsibility Is Clear—Olympiakos Lost Well in Toumba. Available online: https://www.sdna.gr/podosfairo/831095_xekathari-i-eythyni-toy-mpoloni-kalos-ehase-o-olympiakos-stin-toympa-vid (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Semetko, Holli A., and Patti M. Valkenburg. 2000. Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. Journal of Communication 50: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Fuyuan, and Heidi Hatfield Edwards. 2005. Economic individualism, humanitarianism, and welfare reform: A value-based account of framing effects. Journal of Communication 55: 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, Pamela J., and Timothy Vos. 2009. Gatekeeping Theory. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Adam F., and Jennifer Jerit. 2007. Toward a theory relating political discourse, media, and public opinion. Journal of Communication 57: 254–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Lauren Reichart, and Ann Pegoraro. 2020. Media framing of Larry Nassar and the USA gymnastics child sex abuse scandal. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 29: 373–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiliopoulos, Panagiotis. 2007. Violence and Aggression in the Work and Life of PSAT Sports Editors. Thessaloniki: PAN-PAN. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Spiliopoulos, Panagiotis. 2020. Media made sport: The contribution of the Media to the development and dissemination of Sports in Greece. In Sports and Media. Rhetoric, Identities and Representations. Edited by Tsigilis Nikolaos and Diamantis Mastrogiannakis. Thessaloniki: Zygos, pp. 177–209. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Spiliopoulos, Panagiotis, Mastrogiannakis D. Diamantis, Lydia Kokkina, and Nikolaos Tsigilis. 2020. Working in a male-dominated universe: Stereotypical attitudes towards Greek female sports journalists. PANR Journal 685–700. Available online: https://www.panr.com.cy/?p=7398 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Sportime. 2021. Frontpage of Sportime Newspaper 19/8/2021. Available online: https://www.sportime.gr/frontpage/19-8-2021/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- STAR. 2018. “No” to vouvouzeles from FIBA. Prohibits Their Use in Mud Basketball. Available online: https://www.star.gr/eidiseis/athlitika/75971/ochi_stis_vouvouzeles_apo_ti_fiba (accessed on 21 March 2022). (In Greek).

- Starke, Christopher, and Felix Flemming. 2017. Who Is Responsible for Doping in Sports? The Attribution of Responsibility in the German Print Media. Communication & Sport 5: 245–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TA NEA. 2007a. Greece is tired. TA NEA, September 17. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- TA NEA. 2007b. Qualifying Theater. TA NEA, September 17. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- TA NEA. 2015. An inglorious end. The Spaniards’ curse is chasing us”. TA NEA, September 16. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- TA NEA. 2017. The defeat lit fires. TA NEA, September 6. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Tewksbury, David, and Dietram A. Scheufele. 2009. News framing theory and research. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Edited by Bryant Jennings and Mary Beth Oliver. New York: Routledge, pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tuchman, Gaye. 1978. Making News: A Study in the Construction of Reality. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Gorp, Baldwin. 2007. The constructionist approach to framing: Bringing culture back in. Journal of Communication 57: 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Vernikou, Chrisovalantou. 2019. Media, national athletic success and collective identity. Master’s Diploma thesis, Hellenic Open University, Patra, Greek. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Vernikou, Chrisovalantou, and Diamantis Mastrogiannakis. 2020. International athletic events and national identity in the political press: The successes of Eurobasket 1987 and Euro 2004. In Sports and Media. Rhetoric, Identities and Representations. Edited by Tsigilis Nikolaos and Diamantis Mastrogiannakis. Thessaloniki: Zygos, pp. 337–67. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Vetakis. 2009. He is looking for answers. TA NEA, September 16. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Villamar, Jennifer, and Timesha Smith. 2019. Exploring Sports Media: A content analysis on Japan and the United States media coverage during the 2015 Women’s World Cup Final. Journal of Management Science and Business Intelligence 4-2: 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, David H. 2007. Thoughts on Agenda Setting, Framing, and Priming. Journal of Communication 57: 142–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, David, Maxwell McCombs, and Donald L. Shaw. 2004. Agenda-setting research: Issues, attributes, and influences. In Handbook of political communication research. Edited by Kaid Lynda Lee. Mahwah: Erlbaum, pp. 257–282. [Google Scholar]

- Wenner, Lawrence A. 2003. Sport and Mass Media. Athens: Kastaniotis. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- White, Marilyn Domas, and Emily E. Marsh. 2006. Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Library Trends 55: 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willig, Carla. 2015. Qualitative Research in Psychology. Introduction. Athens: Gutenberg. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Xanthiotis, George, Panagiotis Spiliopoulos, and Nikolaos Tsigilis. 2020. Morphological characteristics of the written word in the coverage of basketball games by Greek sports websites. Physical Education & Sports 40: 139. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

| Newspaper | Frame Appearance Frequency (Overall) | Frame Appearance Frequency (the Day after the Game) |

|---|---|---|

| METROSPORT | 40 63.5% | 33 73.3% |

| KATHIMERINI | 4 6.3% | 1 2.25% |

| ETHNOS | 8 12.7% | 2 4.45% |

| TA NEA | 11 17.5% | 9 20% |

| TOTAL | 63 100% | 45 100% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spiliopoulos, P.; Tsigilis, N.; Matsiola, M.; Tsapari, I. The Framing of the National Men’s Basketball Team Defeats in the Eurobasket Championships (2007–2017) by the Greek Press. Journal. Media 2022, 3, 309-329. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3020023

Spiliopoulos P, Tsigilis N, Matsiola M, Tsapari I. The Framing of the National Men’s Basketball Team Defeats in the Eurobasket Championships (2007–2017) by the Greek Press. Journalism and Media. 2022; 3(2):309-329. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpiliopoulos, Panagiotis, Nikolaos Tsigilis, Maria Matsiola, and Ioanna Tsapari. 2022. "The Framing of the National Men’s Basketball Team Defeats in the Eurobasket Championships (2007–2017) by the Greek Press" Journalism and Media 3, no. 2: 309-329. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3020023

APA StyleSpiliopoulos, P., Tsigilis, N., Matsiola, M., & Tsapari, I. (2022). The Framing of the National Men’s Basketball Team Defeats in the Eurobasket Championships (2007–2017) by the Greek Press. Journalism and Media, 3(2), 309-329. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3020023