Climate Change Misinformation in the United States: An Actor–Network Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Approach and Structure

3. Climate Change Misinformation Context and Issues

3.1. CCM in the U.S.

3.2. Notable Findings from Past CCM Studies

4. Understanding CCM Using Social Theory and Concepts

4.1. Actor–Network Theory and Black-Boxing

4.2. CCM in Actor–Network Studies

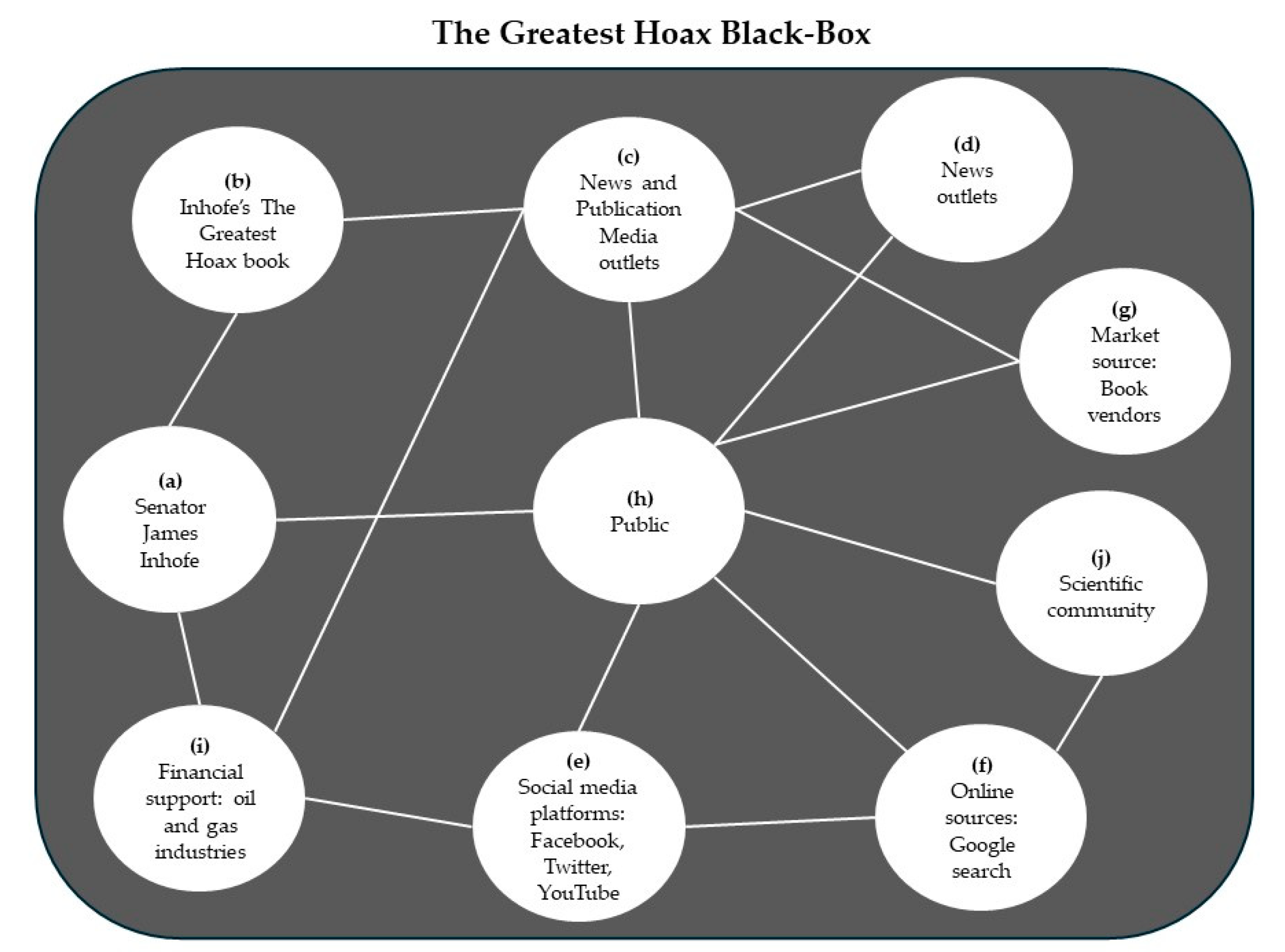

4.3. CCM as a Black box

- (a)

- As a prominent political figure, Senator Inhofe possesses significant power and influence over public opinion and policy decisions regarding climate change. Inhofe has utilized his platform to propagate the narrative of climate change as a hoax, in the process solidifying his position as a leading voice of climate change denial. He authored “The Greatest Hoax: How the Global Warming Conspiracy Threatens Your Future” in 2012, and he has delivered speeches and engaged in public discourse that undermines the credibility of climate science and dismisses the overwhelming evidence supporting anthropogenic climate change. In 2015, he also infamously brought a snowball onto the Senate floor as a prop for his argument that global warming was not real (The Guardian 2015). By disseminating the hoax narrative, he undermines climate science and influences environment- and climate-related policies which threaten the fossil fuel industries. Inhofe is a central actor in the misinformation network, as he fulfills his objective within the misinformation network to advance his political agenda. He also leverages his position as a senator to amplify his hoax narrative.

- (b)

- Inhofe’s book serves as a pivotal actor in spreading CCM. Its objective is to present a persuasive argument that climate change is a hoax, thereby shaping public opinion and influencing policy decisions. Through the dissemination of this book, the hoax narrative of climate change gets reinforced.

- (c)

- Specifically in the case of Senator Inhofe’s book, the publishing house WorldNetDaily (WND)—an American far-right news website—played a role in the black box network by disseminating the book to a wider audience. WND is known for publishing content voiced by or originating from right-wing politicians and pundits (Nelson 2012). By leveraging its platform and audience reach, WND amplifies the narrative of climate change denial presented in Inhofe’s book, contributing to the reinforcement of skepticism surrounding climate science. WND serves as a critical actor in the dissemination of CCM, functioning within a network of interconnected actors. Whether through opinion pieces, news coverage, or social media posts, WND amplifies the climate denial agenda for its audience. Media outlets act as intermediaries within the network, amplifying Inhofe’s narrative to a wider audience. The objective is to attract viewership by catering to the biases and interests of their audience and to perpetuate the hoax narrative and contribute to the dissemination of misinformation on climate change.

- (d)

- Between the publisher and the public, various channels contribute to the dissemination and amplification of Senator Inhofe’s climate change denial narrative. In the case of the publisher, news outlets (including newspapers, television channels, or online websites) are vital in conveying information to the public, amplifying the message of Inhofe’s book through coverage and reporting, simplifying its content, and making it challenging for the public to critically examine climate change denialism.

- (e)

- The dissemination of a false narrative is also often influenced by several interconnected characteristics in a social network (Treen et al. 2020). For example, users on social media platforms are connected to other users through a network of friends, followers, or groups. This is where the role of social media is crucial, because once the misinformation is posted online, it reaches a global audience within a short period of time (Boussalis and Coan 2018). When one user shares false information or a claim about climate change, then it instantly reaches the user’s connections in his or her network. Various studies suggests that Facebook and Twitter are often used to propagate misinformation about climate science to the public (Al-Rawi et al. 2021). In this case, these social media platforms serve as avenues for promoting the book and engaging with supporters, further amplifying the narrative. Supporters of Inhofe’s climate denial narrative may also use specific features on Facebook, such as pages and groups, to promote his book or share excerpts from his book, thereby engaging with like-minded individuals within their network. Moreover, user engagement metrics on Facebook, such as likes, shares, comments, and posts related to Inhofe’s book and its contents, may also provide insights into public interest and interaction with the CCM narrative. Other social media platform products like YouTube videos, capable of going viral, may provide another avenue for spreading Inhofe’s message widely and swiftly, reinforcing the simplicity of the narrative and impeding public inquiry.

- (f)

- Google searches, a common source of online information, may also direct individuals to resources related to Inhofe’s book, perpetuating the simplified narrative and obstructing critical examination.

- (g)

- Book vendors and online sellers, such as Amazon, facilitate the accessibility of Inhofe’s book to a broader audience, contributing to the amplification of the narrative and reinforcing the black-boxing of CCM. Moreover, reviews and recommendations by like-minded individuals and groups on these platforms may further influence the public’s decision to engage with the book and its contents, contributing to promoting more discussion around this narrative.

- (h)

- The public absorbs and internalizes the message that climate change is a hoax through repeated exposure to misinformation. They serve as both recipients and interpreters of misinformation propagated by Inhofe and other actors within the network. Their objective is to make sense of the information they encounter and form opinions on climate change based on the narratives presented to them. By consuming and internalizing the hoax narrative, individuals may develop skepticism towards climate science and resist calls for action on climate change (Treen et al. 2020). The general public serves as the audience for Inhofe’s book and other forms of media that perpetuate CCM.

- (i)

- According to a 2019 report, Senator Inhofe received USD 1,530,500 from the fossil fuel industry during his career to disprove climate change (Geary 2019). Furthermore, between 1989 and 2020, Senator Inhofe received significant funding from various entities with vested interests in the oil and gas industries, namely, Koch Industries and American Consolidated Natural Resources, to contribute to Inhofe’s climate denial campaigns (McKie 2023). Similarly, Senator Inhofe had strong connections with organizations known for opposing climate change action, such as the Heartland Institute, an American conservative and libertarian think tank well-known for climate change skepticism (Boykoff 2023). The financial support and platform from corporations, think tanks, and other entities sharing a common goal has a role in amplifying climate denial voices. In this way, this kind of support has been leveraged in the creation of a network of like-minded individuals and entities to reinforce the narrative that climate change is a hoax. They further bolster skepticism towards climate science and maintain their dominance in society.

- (j)

- Although, the scientific community strives to communicate the consensus on anthropogenic climate change and the need for urgent action, their efforts are often discredited by actors like Inhofe, who deny that climate change is caused by humans (Petersen et al. 2019). The dissemination of hoax narratives undermines public trust in scientific information and leads to doubts about the reality of climate change. The emergence and reproduction of false or fabricated information or news regarding climate change, which infiltrates the scientific community, may result in a whirlwind of concerns and discussions surrounding such information (Alonso García et al. 2020).

5. Counteracting Measures against Climate Change Misinformation

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Extracted definition from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/misinformation (accessed on 22 April 2024). |

| 2 | Extracted definition from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/disinformation (accessed on 22 April 2024). |

| 3 | https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bruno-Latour (accessed on 22 April 2024). |

References

- Almiron, Núria, Jose A. Moreno, and Justin Farrell. 2023. Climate change contrarian think tanks in Europe: A network analysis. Public Understanding of Science 32: 268–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso García, Santiago, Gerardo Gómez García, Mariano Sanz Prieto, Antonio J. Moreno Guerrero, and Carmen Rodríguez Jiménez. 2020. The Impact of Term Fake News on the Scientific Community. Scientific Performance and Mapping in Web of Science. Social Sciences 9: 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawi, Ahmed, Derrick O’Keefe, Oumar Kane, and Aimé-Jules Bizimana. 2021. Twitter’s Fake News Discourses Around Climate Change and Global Warming. Frontiers in Communication 6: 729818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoruso, Marco, Daniele Anello, Vincenzo Auletta, Raffaele Cerulli, Diodato Ferraioli, and Andrea Raiconi. 2020. Contrasting the Spread of Misinformation in Online Social Networks. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 69: 847–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Neela. 2017. How Big Oil Lost Control of Its Climate Misinformation Machine. Available online: https://insideclimatenews.org/news/22122017/big-oil-heartland-climate-science-misinformation-campaign-koch-api-trump-infographic/ (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- Bast, Joseph L. 2013. IPCC Exaggerates Risks: Opposing View. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Bayes, Robin, Toby Bolsen, and James N. Druckman. 2023. A Research Agenda for Climate Change Communication and Public Opinion: The Role of Scientific Consensus Messaging and Beyond. Environmental Communication 17: 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernauer, Thomas. 2013. Climate Change Politics. Annual Review of Political Science 16: 421–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björklund, Erik. 2022. The Cultural Production of Climate Disinformation: A Social Network Analysis of the NIPCC. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1685766/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Bloomfield, Emma Frances, and Denise Tillery. 2019. The Circulation of Climate Change Denial Online: Rhetorical and Networking Strategies on Facebook. Environmental Communication 13: 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsen, Toby, and James N. Druckman. 2015. Counteracting the Politicization of Science. Journal of Communication 65: 745–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsen, Toby, and James N. Druckman. 2018. Do partisanship and politicization undermine the impact of a scientific consensus message about climate change? Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 21: 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussalis, Constantine, and Travis G. Coan. 2018. Commentary on “Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and coping with the post-truth era”. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 6: 405–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, Maxwell T. 2008. Lost in Translation? United States Television News Coverage of Anthropogenic Climate Change, 1995–2004. Climatic Change 86: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, Maxwell T. 2023. Climate change counter movements and adaptive strategies: Insights from Heartland Institute annual conferences a decade apart. Climatic Change 177: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, Maxwell T., and Jules M. Boykoff. 2007. Climate Change and Journalistic Norms: A Case-Study of US Mass-Media Coverage. Geoforum 38: 1190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Rupert. 2000. Social identity theory: Past achievements, current problems and future challenges. European Journal of Social Psychology 30: 745–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, Michel, and Bruno Latour. 1981. Leviathan: How Actors Macro-Structure Reality and How Sociologists Help Them to Do So. Available online: http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/09-LEVIATHAN-GB.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Carvalho, Anabela. 2010. Media (Ted) Discourses and Climate Change: A Focus on Political Subjectivity and (Dis)Engagement. WIREs Climate Change 1: 172–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Sijing, Lu Xiao, and Akit Kumar. 2023. Spread of Misinformation on Social Media: What Contributes to It and How to Combat It. Computers in Human Behavior 141: 107643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Brett, and Richard York. 2005. Carbon metabolism: Global capitalism, climate change, and the biospheric rift. Theory and Society 34: 391–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colston, Nicole M., and Toni A. Ivey. 2015. (un)Doing the Next Generation Science Standards: Climate change education actor-networks in Oklahoma. Journal of Education Policy 30: 773–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, John. 2019. Understanding and Countering Misinformation about Climate Change. In Handbook of Research on Deception, Fake News, and Misinformation Online. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, John, Stephan Lewandowsky, and Ullrich K. H. Ecker. 2017. Neutralizing Misinformation through Inoculation: Exposing Misleading Argumentation Techniques Reduces Their Influence. PLoS ONE 12: e0175799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordella, Antonio, and Maha Shaikh. 2003. Actor Network Theory and After: What’s New for IS Research? ECIS 2003 Proceedings. January. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/48909918_Actor-network_theory_and_after_what’s_new_for_IS_research (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Crawford, T. Hugh. 2020. Actor-Network Theory. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressman, Darryl. 2009. A Brief Overview of Actor-Network Theory: Punctualization, Heterogeneous Engineering & Translation. Available online: https://summit.sfu.ca/item/13593 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Cresswell, Kathrin M., Allison Worth, and Aziz Sheikh. 2010. Actor-Network Theory and its role in understanding the implementation of information technology developments in healthcare. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 10: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabla-Norris, Era, Thomas Helbling, Salma Khalid, Hibah Khan, Giacomo Magistretti, Alexandre Sollaci, and Krishna Srinivasan. 2023. Public Perceptions of Climate Mitigation Policies: Evidence from Cross-Country Surveys. Staff Discussion Notes 2023 (002). Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/006/2023/002/article-A001-en.xml (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Claire Parnet. 2007. Dialogues II. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Ding, Edward W. Maibach, Xiaoquan Zhao, Connie Roser-Renouf, and Anthony Leiserowitz. 2011. Support for Climate Policy and Societal Action Are Linked to Perceptions about Scientific Agreement. Nature Climate Change 1: 462–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolwick, Jim S. 2009. ‘The Social’ and Beyond: Introducing Actor-Network Theory. Journal of Maritime Archaeology 4: 21–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckman, James N. 2017. The Crisis of Politicization within and beyond Science. Nature Human Behaviour 1: 615–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsasser, Shaun W., and Riley E. Dunlap. 2013. Leading Voices in the Denier Choir: Conservative Columnists’ Dismissal of Global Warming and Denigration of Climate Science. American Behavioral Scientist 57: 754–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency. 2024. Overview of Greenhouse Gases. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases#:~:text=Global%20Warming%20Potential%20(100%2Dyear,gas%20emissions%20from%20human%20activities (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Farmer, G. Thomas, and John Cook. 2013. Understanding Climate Change Denial. In Climate Change Science: A Modern Synthesis: Volume 1—The Physical Climate. Edited by Farmer G. Thomas and John Cook. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 445–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, Justin. 2016. Network structure and influence of the climate change counter-movement. Nature Climate Change 6: 370–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, Justin, Kathryn McConnell, and Robert Brulle. 2019. Evidence-Based Strategies to Combat Scientific Misinformation. Nature Climate Change 9: 191–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, Justin. 2019. The growth of climate change misinformation in US philanthropy: Evidence from natural language processing. Environmental Research Letters 14: 034013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, Tara, and Richard Edwards. 2010. Actor-Network Theory in Education. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, Ben. 2005. From Actor-Network Theory to Political Economy. Capitalism Nature Socialism 16: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franta, Benjamin. 2021. Early Oil Industry Disinformation on Global Warming. Environmental Politics 30: 663–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, Pierre, Michael O’Sullivan, Matthew W. Jones, Robbie M. Andrew, Judith Hauck, Are Olsen, Glen P. Peters, Wouter Peters, Julia Pongratz, Stephen Sitch, and et al. 2020. Global Carbon Budget 2020. Earth System Science Data 12: 3269–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, Cary, and Brian Kennedy. 2016. The Politics of Climate. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2016/10/04/the-politics-of-climate/ (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Gabbatiss, Josh. 2021. The Carbon Brief Profile: United States. Carbon Brief. Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org/the-carbon-brief-profile-united-states/ (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Geary, John. 2019. The Dark Money of Climate Change. ESSAI 17. Available online: https://dc.cod.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1691&context=essai (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Gopal, Keerti. 2023. Mike Huckabee’s “Kids Guide to the Truth About Climate Change” Shows the Changing Landscape of Climate Denial. Inside Climate News. Available online: https://insideclimatenews.org/news/31072023/huckabees-kids-guide-to-climate/ (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Gromet, Dena M., Howard Kunreuther, and Richard P. Larrick. 2013. Political ideology affects energy-efficiency attitudes and choices. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: 9314–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, Andrew M., and Benjamin A. Lyons. 2020. Misinformation, Disinformation, and Online Propaganda. In Social Media and Democracy. Edited by Joshua A. Tucker and Nathaniel Persily. SSRC Anxieties of Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 10–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Shannon. 2015. Exxon Knew about Climate Change Almost 40 Years Ago. Scientific American. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/exxon-knew-about-climate-change-almost-40-years-ago/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Hassan, Isyaku, Rabiu M. Musa, Mohd Nazri Latiff Azmi, Mohamad Razali Abdullah, and Siti Zanariah Yusoff. 2023. Analysis of climate change disinformation across types, agents and media platforms. Information Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicke, Jeffrey A., Simone Lucatello, Linda D. Mortsch, Jackie Dawson, Mauricio Domínguez Aguilar, Carolyn A. F. Enquist, Elisabeth A. Gilmore, David S. Gutzler, Sherilee Harpe, Kirstin Holsman, and et al. 2022. North America. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1929–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inhofe, James. 2012. The Greatest Hoax: How the Global Warming Conspiracy Threatens Your Future, 1st ed. Washington, DC: WND Books. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 1992. Climate Change: The IPCC 1990 and 1992 Assessments. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/ipcc_90_92_assessments_far_full_report.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- IPCC. 1995. Climate Change 1995: IPCC Second Assessment Report. Available online: https://archive.ipcc.ch/pdf/climate-changes-1995/ipcc-2nd-assessment/2nd-assessment-en.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- IPCC. 2001. Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by Robert T. Watson and the Core Writing Team. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 2007. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by the Core Writing Team, Rajendra K. Pachauri and Andy Reisinger. Geneva: IPCC. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by the Core Writing Team, Rajendra K. Pachauri and Leo A. Meyer. Geneva: IPCC. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 2021. Climate Change Widespread, Rapid, and Intensifying—IPCC. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/2021/08/09/ar6-wg1-20210809-pr/ (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- IPCC. 2023. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by the Core Writing Team, Hoesung Lee and José Romero. Geneva: IPCC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Md Saidul, and Edson Kieu. 2021. Sociological Perspectives on Climate Change and Society: A Review. Climate 9: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, Shanto, and Masha Krupenkin. 2018. Partisanship as Social Identity; Implications for the Study of Party Polarization. The Forum 16: 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlova, Natascha, and Karen E. Fisher. 2012. “Plz RT”: A social diffusion model of misinformation and disinformation for understanding human behaviour. Paper presented at the ISIC2012, Tokyo, Japan, September 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Krarup, Troels Magelund, and Anders Blok. 2011. Unfolding the Social: Quasi-Actants, Virtual Theory, and the New Empiricism of Bruno Latour. The Sociological Review 59: 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkonen, Anna, Mark C. Stoddart, and Tuomas Ylä-Anttila. 2021. Actors and justifications in media debates on Arctic climate change in Finland and Canada: A network approach. Acta Sociologica 64: 103–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahsen, Myanna. 1999. The Detection and Attribution of Conspiracies. In Paranoia within Reason: A Casebook on Conspiracy as Explanation. Late Editions: Cultural Studies for the End of the Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Available online: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/P/bo3626884.html (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Latour, Bruno. 1987. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 1994. On Technical Mediation. Common Knowledge 3: 29–64. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 1999. Pandora’s Hope. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Available online: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674653368 (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Law, John. 1992. Notes on the Theory of the Actor-Network: Ordering, Strategy, and Heterogeneity. Systems Practice 5: 379–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, Eva K., and Sarah Estow. 2017. Responding to misinformation about climate change. Applied Environmental Education and Communication 16: 117–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, David, Matthew Baum, Nir Grinberg, Lisa Friedland, Kenneth Joseph, Will Hobbs, and Carolina Mattsson. 2017. Combating Fake News: An Agenda for Research and Action. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-05/apo-nid76233.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Lewandowsky, Stephan. 2021. Climate Change Disinformation and How to Combat It. Annual Review of Public Health 42: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Gilles Gignac, and Samuel Vaughan. 2013. The Pivotal Role of Perceived Scientific Consensus in Acceptance of Science. Nature Climate Change 3: 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Ullrich K. H. Ecker, and John Cook. 2017. Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the “Post-Truth” Era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 6: 353–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linfield, Mark. 2011. Frozen Planet. BBC Earth. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2092588/fullcredits (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Maertens, Rakoen, Frederik Anseel, and Sander van der Linden. 2020. Combatting Climate Change Misinformation: Evidence for Longevity of Inoculation and Consensus Messaging Effects. Journal of Environmental Psychology 70: 101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, Yadvinder, Janet Franklin, Nathalie Seddon, Martin Solan, Monica G. Turner, Christopher B. Field, and Nancy Knowlton. 2020. Climate Change and Ecosystems: Threats, Opportunities and Solutions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 375: 20190104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlon, Jennifer, Liz Neyens, Martial Jefferson, Peter Howe, Matto Mildenberger, and Anthony Leiserowitz. 2021. Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2021—Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Available online: https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us/ (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Marwick, Alice E. 2018. Why Do People Share Fake News? A Sociotechnical Model of Media Effects. Georgetown Law Technology Review. Available online: https://georgetownlawtechreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/2.2-Marwick-pp-474-512.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Matthews, Dylan. 2017. Donald Trump Has Tweeted Climate Change Skepticism 115 Times. Here’s All of It. Vox. Available online: https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/6/1/15726472/trump-tweets-global-warming-paris-climate-agreement (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- McCright, M. Aaron, Riley E. Dunlap, and Chenyang Xiao. 2013. Perceived scientific agreement and support for government action on climate change in the USA. Climatic Change 119: 511–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKie, Ruth E. 2023. The Foundations of the Climate Change Counter Movement: United States of America. In The Climate Change Counter Movement: How the Fossil Fuel Industry Sought to Delay Climate Action. Edited by Ruth E. McKie. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawararthne, Dilina, and Cristiano Storni. 2023. Black-boxing Journalistic Chains, an Actor-network Theory Inquiry into Journalistic Truth. Journalism Studies 24: 1629–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neisser, Florian M. 2014. ‘Riskscapes’ and risk management—Review and synthesis of an actor-network theory approach. Risk Management 16: 88–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Leah. 2012. Worldnet Daily Continues to Pump out Outrageous Propaganda. Available online: https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2012/worldnet-daily-continues-pump-out-outrageous-propaganda (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Newton, Tim J. 2002. Creating the New Ecological Order? Elias and Actor-Network Theory. The Academy of Management Review 27: 523–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, Brendan, Susan Ciccotosto, and Paul De Lange. 2014. Understanding the Application of Actor-Network Theory in the Process of Accounting Change. Toronto: Schulich School of Business. Available online: https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/34366/ (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Oreskes, Naomi, and Erik M. Conway. 2011. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook, Gordon, Adam Bear, Evan T. Collins, and David G. Rand. 2020. The Implied Truth Effect: Attaching Warnings to a Subset of Fake News Headlines Increases Perceived Accuracy of Headlines Without Warnings. Management Science 66: 4944–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Gordon, and David G. Rand. 2019. Fighting Misinformation on Social Media Using Crowdsourced Judgments of News Source Quality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116: 2521–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, Brian, Dlana Stuart, and Ryan Gunderson. 2019. Reconceptualizing Climate Change Denial: Ideological Denialism Misdiagnoses Climate Change and Limits Effective Action. Human Ecology Review 25: 117–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper-Wright, Tracy. 2020. Between Presence and Program: The Photographic Error as Counter Culture. In Technology, Design and the Arts—Opportunities and Challenges. Edited by Rae Earnshaw, Susan Liggett, Peter Excell and Daniel Thalmann. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 139–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poortinga, Wouter, Alexa Spence, Lorraine Whitmarsh, Stuart Capstick, and Nick F. Pidgeon. 2011. Uncertain climate: An investigation into public scepticism about anthropogenic climate change. Global Environmental Change 21: 1015–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rannard, Georgina. 2023. ExxonMobil: Oil Giant Predicted Climate Change in 1970s—Scientists. BBC News 2023, Sec. Science & Environment. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-64241994 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Readfearn, Graham. 2016. Revealed: Most Popular Climate Story on Social Media Told Half a Million People the Science Was a Hoax. Available online: https://www.desmogblog.com/2016/11/29/revealed-most-popular-climate-story-social-media-told-half-million-people-science-was-hoax (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- Robinson, Elmer, and Robert C. Robbins. 1968. Sources, Abundance, and Fate of Gaseous Atmospheric Pollutants. Final Report and Supplement. United States. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/6852325 (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Rode, B. Jacob, Amy L. Dent, Caitlin N. Benedict, Daniel B. Brosnahan, Ramona L. Martinez, and Peter H. Ditto. 2021. Influencing climate change attitudes in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology 76: 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Hector. 2009. The Black Box. Available online: http://95.216.75.113:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/164/Rodriguez_The%20Black%20Box.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Sarathchandra, Dilshani, and Kristin Haltinner. 2021. How Believing Climate Change is a “Hoax” Shapes Climate Skepticism in the United States. Environmental Sociology 7: 225–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Petri, Hannah, and Moritz Bürger. 2022. The Effect of Misinformation and Inoculation: Replication of an Experiment on the Effect of False Experts in the Context of Climate Change Communication. Public Understanding of Science 31: 152–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Chengcheng, Giovanni Luca Ciampaglia, Onur Varol, Kai-Cheng Yang, Alessandro Flammini, and Filippo Menczer. 2018. The Spread of Low-Credibility Content by Social Bots. Nature Communications 9: 4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvis, Emile, and Patricia M. Alexander. 2014. A study using a graphical syntax for actor-network theory. Information Technology & People 27: 110–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalph, Florian. 2019. Hybrids, materiality, and black boxes: Concepts of actor-network theory in data journalism research. Sociology Compass 13: e12738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanforth, Carolyne. 2006. Using Actor-Network Theory to Analyze E-Government Implementation in Developing Countries. Information Technologies & International Development 3: 35–60. [Google Scholar]

- Stoetzer, Lasse S., and Florian Zimmermann. 2024. A Representative Survey Experiment of Motivated Climate Change Denial. Nature Climate Change 14: 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supran, Geoffrey, Stefan Rahmstorf, and Naomi Oreskes. 2023. Assessing ExxonMobil’s global warming projections. Science 379: eabk0063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Guardian. 2015. Republican Senate Environment Chief Uses Snowball as Prop in Climate Rant. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/feb/26/senate-james-inhofe-snowball-climate-change (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Thuiller, Wilfried. 2007. Climate change and ecologists. Nature 448: 550–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treen, Kathie M. d’I., Hywel T. P. Williams, and Saffron J. O’Neill. 2020. Online Misinformation about Climate Change. WIREs Climate Change 11: e665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Joshua, Andrew Guess, Pablo Barbera, Cristian Vaccari, Alexandra Siegel, Sergey Sanovich, Denis Stukal, and Brendan Nyhan. 2018. Social Media, Political Polarization, and Political Disinformation: A Review of the Scientific Literature.SSRN Scholarly Paper. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3144139. (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Turrentine, Jeff. 2022. Climate Misinformation on Social Media is Undermining Climate Action. Climate Misinformation on Social Media Is Undermining Climate Action. Available online: https://www.nrdc.org (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- U.S. Global Change Research Program. 2009. Climate Literacy: The Essential Principles of Climate Sciences. Available online: https://www.globalchange.gov/browse/reports/climateliteracy-essential-principles-climate-science-high-resolution-booklet (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- U.S. Global Research Program. 2014. Climate Change Impact in the United States: Climate Trends and Regional Impacts. NCA3-Climate-Trends-Regional-Impacts-Brochure.pdf. Available online: https://globalchange.gov (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- van der Linden, Sander. 2022. Misinformation: Susceptibility, Spread, and Interventions to Immunize the Public. Nature Medicine 28: 460–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, Sander, Anthony Leiserowitz, Seth Rosenthal, and Edward Maibach. 2017. Inoculating the Public against Misinformation about Climate Change. Global Challenges 1: 1600008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessells, Anne Taufen. 2007. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory by Bruno Latour. International Public Management Journal 10: 351–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, Andrea, and André Spicer. 2008. Is Actor Network Theory Critique? Organization Studies 29: 611–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuebbles, Donald, David W. Fahey, and Kathleen A. Hibbard. 2017a. How Will Climate Change Affect the United States in Decades to Come? Available online: https://eos.org/features/how-will-climate-change-affect-the-united-states-in-decades-to-come (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Wuebbles, Donald, David W. Fahey, Kathleen A. Hibbard, David J. Dokken, Brooke C. Stewart, and Thomas K. Maycock. 2017b. Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment Volume 1. Washington, DC: United States Global Change Research Program, p. 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Aimei. 2024a. What Makes a Climate Change Denier Popular? Exploring Networked Social Influence in a Disinformation Spreader Group. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10125/106724 (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Yang, Aimei. 2024b. Exploring the Network and Topic Stability in Climate Change Deniers’ Disinformation Network: A Longitudinal Study. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10125/106714 (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Yao, Song, and Kui Liu. 2022. Actor-Network Theory: Insights into the Study of Social-Ecological Resilience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 16704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Yanmengqian, and Lijiang Shen. 2022. Confirmation Bias and the Persistence of Misinformation on Climate Change. Communication Research 49: 500–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thapa Magar, N.; Thapa, B.J.; Li, Y. Climate Change Misinformation in the United States: An Actor–Network Analysis. Journal. Media 2024, 5, 595-613. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020040

Thapa Magar N, Thapa BJ, Li Y. Climate Change Misinformation in the United States: An Actor–Network Analysis. Journalism and Media. 2024; 5(2):595-613. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020040

Chicago/Turabian StyleThapa Magar, Neelam, Binay Jung Thapa, and Yanan Li. 2024. "Climate Change Misinformation in the United States: An Actor–Network Analysis" Journalism and Media 5, no. 2: 595-613. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020040

APA StyleThapa Magar, N., Thapa, B. J., & Li, Y. (2024). Climate Change Misinformation in the United States: An Actor–Network Analysis. Journalism and Media, 5(2), 595-613. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020040