Digital Video Advertising: Breakthrough or Extension of TV Advertising in the New Digital Media Landscape?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

2.1. Overview of the Digital Marketing Literature

2.2. Digital Video Advertising in the New Media Landscape

2.3. Digital Video Advertising versus Television Advertising

2.4. YouTube Advertising Platform

3. Aim, Hypothesis, and Research Question

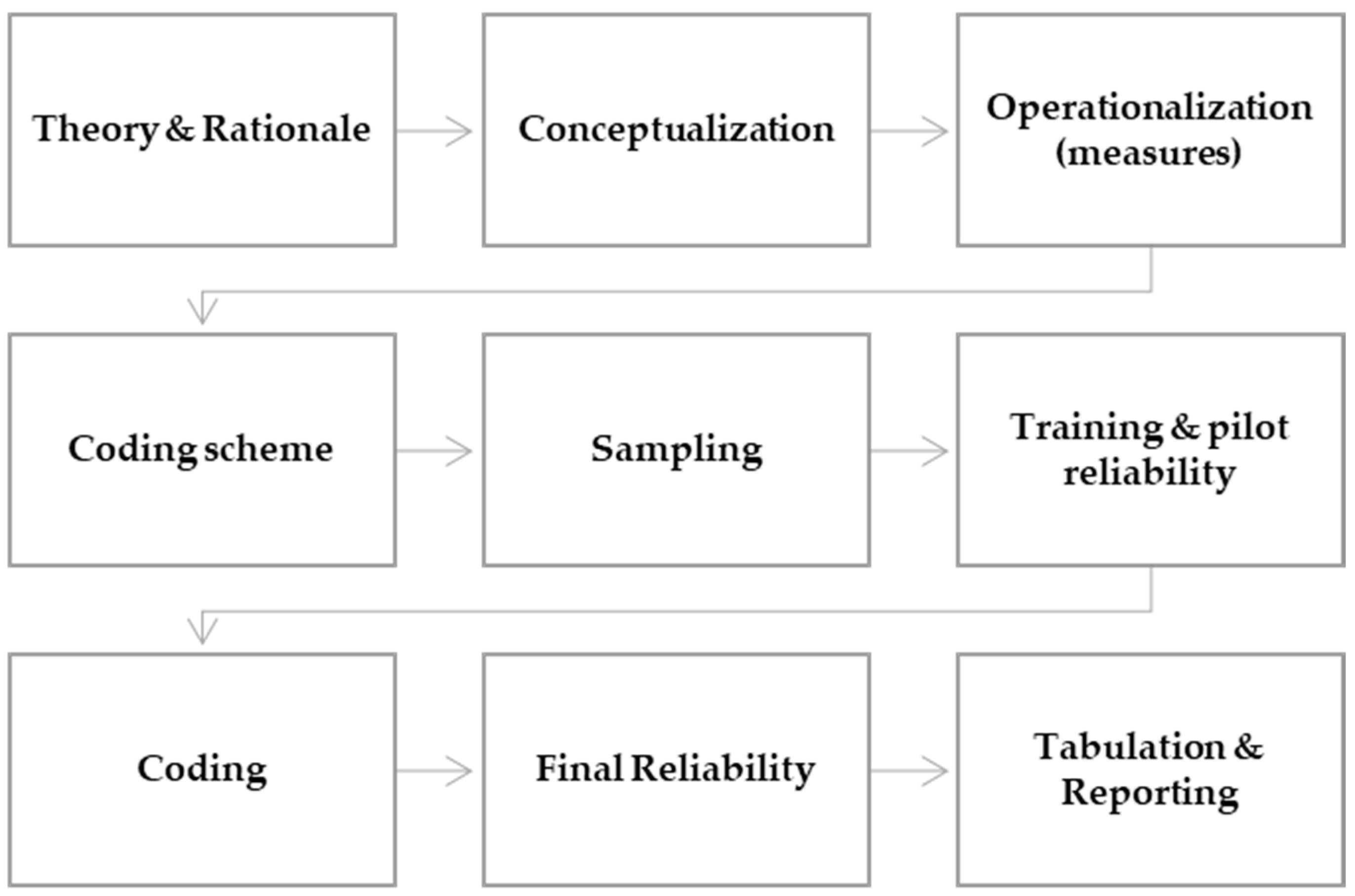

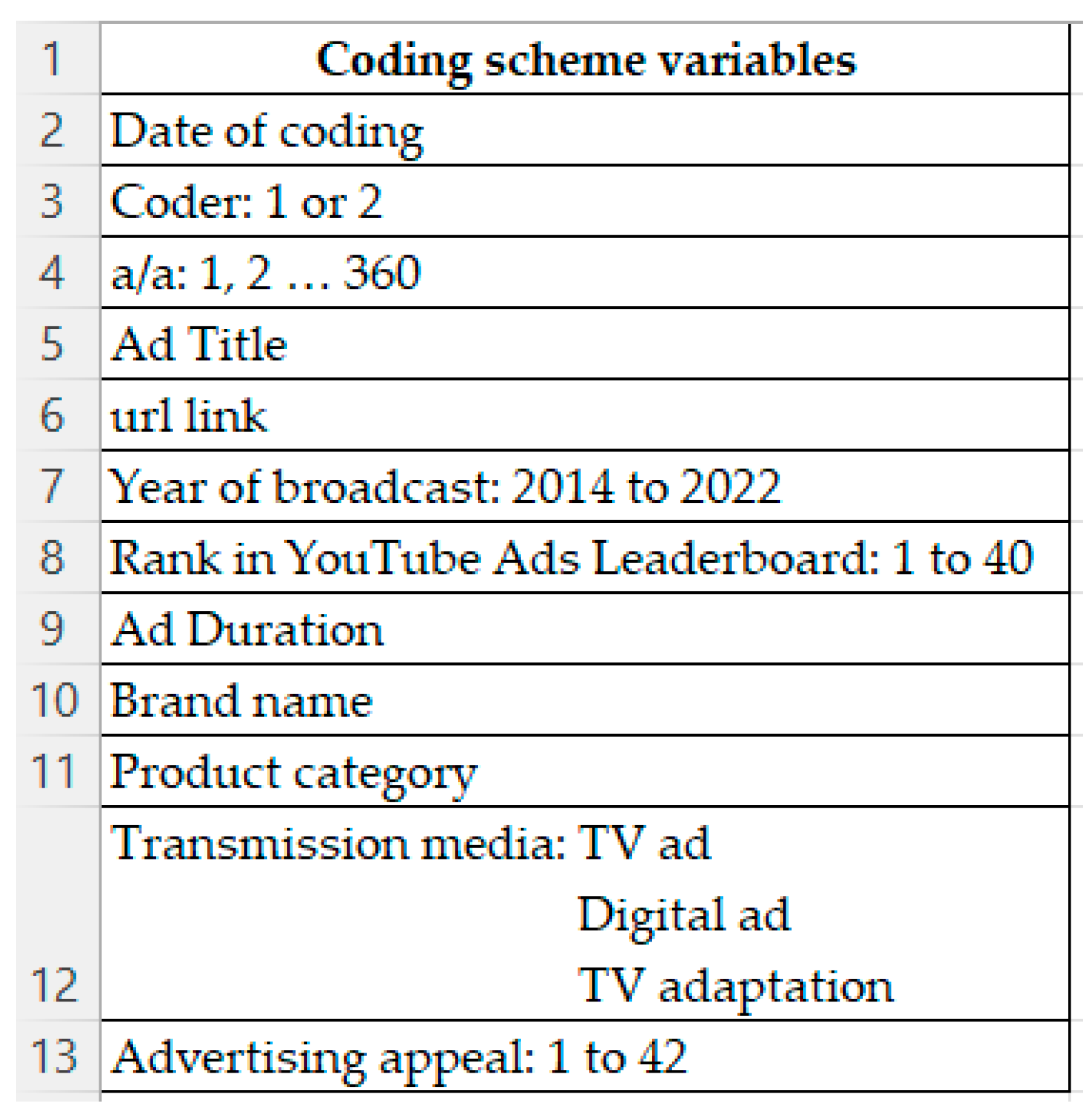

4. Methodology

5. Analysis and Results

5.1. Product Categories

5.2. Transmission Media and Ad Duration

5.3. Popular Advertising Content

6. Discussion

7. Managerial Implications and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Rational Appeals | Emotional Appeals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/A | Advertising Appeal | A/A | Advertising Appeal | A/A | Advertising Appeal |

| 1 | Effective | 1 | Ornamental | 15 | Plain |

| 2 | Durable | 2 | Dear | 16 | Frail |

| 3 | Convenient | 3 | Distinctive | 17 | Adventure |

| 4 | Cheap | 4 | Popular | 18 | Untamed |

| 5 | Modern | 5 | Traditional | 19 | Freedom |

| 6 | Natural | 6 | Magic | 20 | Casual |

| 7 | Technological | 7 | Relaxation | 21 | Vain |

| 8 | Wisdom | 8 | Enjoyment | 22 | Sexuality |

| 9 | Productivity | 9 | Maturity | 23 | Status |

| 10 | Tamed | 10 | Youth | 24 | Affiliation |

| 11 | Independence | 11 | Safety | 25 | Nurturance |

| 12 | Health | 12 | Morality | 26 | Succorance |

| 13 | Security | 13 | Modesty | 27 | Family |

| 14 | Humility | 28 | Community | ||

| 29 | Neat | ||||

References

- Albers-Miller, Nancy D., and Marla Royne Stafford. 1999. An International Analysis of Emotional and Rational Appeals in Services vs Goods Advertising. Journal of Consumer Marketing 16: 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexa. 2020. Youtube.Com Competitive Analysis, Marketing Mix and Traffic. Alexa Internet. Available online: http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/youtube.com (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Appel, Gil, Lauren Grewal, Rhonda Hadi, and Andrew T. Stephen. 2020. The Future of Social Media in Marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 48: 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, Salman. 2020. YouTube by the Numbers (2020): Stats, Demographics & Fun Facts. Available online: https://www.omnicoreagency.com/youtube-statistics/ (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Associated Press. 2021. Facebook Wants to Lean into the Metaverse. Here’s What It Is and How It Will Work. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2021/10/28/1050280500/ (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Barnes, Stuart J. 2002. Wireless Digital Advertising: Nature and Implications. International Journal of Advertising 21: 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. 1999. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Choice Reviews Online. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzinski, Oliver, Sophia Gaenssle, and Nadine Lindstädt-Dreusicke. 2021. The Battle of YouTube, TV and Netflix: An Empirical Analysis of Competition in Audiovisual Media Markets. SN Business & Economics 1: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callcott, Margaret F., and Wei Na Lee. 1994. A Content Analysis of Animation and Animated Spokes-Characters in Television Commercials. Journal of Advertising 23: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, Laura. 2024. Worldwide Advertising Revenues of YouTube from 2017 to 2023. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/289658/youtube-global-net-advertising-revenues/ (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Chandrasekar, Chaitanya. 2018. How Digital Video Advertising Will Dominate the Next Decade. Available online: https://www.searchenginejournal.com/digital-video-advertising-domination/256031/#close (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Chang, Yuhmiin, and Esther Thorson. 2004. Television and Web Advertising Synergies. Journal of Advertising 33: 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Julian Ming Sung, Charles Blankson, Edward Shih Tse Wang, and Lily Shui Lien Chen. 2009. Consumer Attitudes and Interactive Digital Advertising. International Journal of Advertising 28: 501–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisco. 2020. Cisco Annual Internet Report (2018–2023) White Paper. Available online: https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/solutions/collateral/executive-perspectives/annual-internet-report/white-paper-c11-741490.html (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Collins, Sean. 2024. 42 YouTube Stats to Know in 2024. Semrush Blog. Available online: https://www.semrush.com/blog/youtube-stats/ (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Cruz-Silva, Jorge, and Marco López-Paredes. 2022. Content Selection Trace Among Media Platforms. In Communication and Applied Technologies. Edited by Paulo Carlos López-López, Daniel Barredo, Ángel Torres-Toukoumidis, Andrea De-Santis and Óscar Avilés. Cuenca: Spinger, pp. 169–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Stuart, David Craig, and Jon Silver. 2016. YouTube, Multichannel Networks and the Accelerated Evolution of the New Screen Ecology. Convergence 22: 376–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Stephan, Lynne Eagle, and Carlos Báez. 2009. Analyzing Advergames: Active Diversions or Actually Deception. An Exploratory Study of Online Advergames Content. Young Consumers 10: 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mooij, Marieke. 2007. Global Marketing and Advertising: Understanding Cultural Paradoxes, 3rd ed. New York: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- DMI. 2020. The Importance of Video Marketing. Available online: https://digitalmarketinginstitute.com/blog/the-importance-of-video-marketing (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Friedman, Wayne. 2017. Shorter-Duration TV Commercials On The Rise. Television News Daily. Available online: https://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/308248/shorter-duration-tv-commercials-on-the-rise.html (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Garganas, Odysseas. 2021. Online Advertising and Global Consumer Culture. Comparative Analysis of the Most Popular Greek and International Advertisements on YouTube. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Available online: http://www.ufrgs.br/actavet/31-1/artigo552.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Geuens, Maggie, Patrick De Pelsmacker, and Tine Faseur. 2011. Emotional Advertising: Revisiting the Role of Product Category. Journal of Business Research 64: 418–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Adam. 2020. The State of Video Marketing in 2020 [New Data]. Available online: https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/state-of-video-marketing-new-data (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Hudson, Simon, and David Hudson. 2006. Branded Entertainment: A New Advertising Technique or Product Placement in Disguise? Journal of Marketing Management 22: 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Simon. 2023. Digital 2023 October Global Statshot Report. Datareportal. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-october-global-statshot (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Kim, Jooyoung. 2021. Advertising in the Metaverse: Research Agenda. Journal of Interactive Advertising 21: 141–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Soojung, Joonghwa Lee, and Jisu Huh. 2019. Digital Video Advertising. In Advertising Theory, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Knoll, Johannes, and Jörg Matthes. 2017. The Effectiveness of Celebrity Endorsements: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 45: 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, Philip, Hermawan Kartajaya, and Iwan Setiawan. 2023. Marketing 6.0: The Future Is Immersive, 1st ed. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2018. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishen, Anjala S., Yogesh K. Dwivedi, N. Bindu, and K. Satheesh Kumar. 2021. A Broad Overview of Interactive Digital Marketing: A Bibliometric Network Analysis. Journal of Business Research 131: 183–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Vishal. 2017. Integrating Theory and Practice in Marketing. Journal of Marketing 81: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudon, Kenneth C., and Carol Traver. 2014. Hλεκτρονικό Εμπόριο 2014. Aθήγνα: Παπασωτηρίου. [Google Scholar]

- Lebow, Sara. 2023. Digital Ad Spend Worldwide to Pass $600 Billion This Year. EMARKETER. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/digital-ad-spend-worldwide-pass-600-billion-this-year (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Leckenby, John D., and Hairong Li. 2000. Why We Need the Journal of Interactive Advertising. Journal of Interactive Advertising 1: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Heejun, and Chang Hoan Cho. 2020. Digital Advertising: Present and Future Prospects. International Journal of Advertising 39: 332–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichtman Research Group. 2023. Major Pay-TV Providers Lost About 465,000 Subscribers in 3Q 2023. Durham: Leichtman Research Group. Available online: https://leichtmanresearch.com/ (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Leiss, William, Stephen Kline, Sut Jhally, and Jackie Boterill. 2005. Social Communication in Advertising: Consumption in the Mediated Marketplace. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lobschat, Lara, Ernst C. Osinga, and Werner J. Reinartz. 2017. What Happens Online Stays Online? Segment-Specific Online and Offline Effects of Banner Advertisements. Journal of Marketing Research 54: 901–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthouse, Edward C., Ewa Maslowska, and Judy U. Franks. 2018. Understanding Programmatic TV Advertising. International Journal of Advertising 37: 769–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuarrie, Edward F., and Barbara J. Phillips. 2008. It’s Not Your Father’s Magazine Ad. Magnitude and Direction of Recent Changes in Advertising Style. Journal of Advertising 37: 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, Neil. 2024. Letter from the YouTube CEO: 4 Big Bets for 2024. Youtube. Available online: https://blog.youtube/inside-youtube/2024-letter-from-neal/ (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Neuendorf, Kimberly A. 2002. The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, Shintaro, and Charles R. Taylor. 2013. Social Media and International Advertising: Theoretical Challenges and Future Directions. International Marketing Review 30: 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, Mary Beth, and Arthur A. Raney. 2011. Entertainment as Pleasurable and Meaningful: Identifying Hedonic and Eudaimonic Motivations for Entertainment Consumption. Journal of Communication 61: 984–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, Marco López, Andrea Carrillo Andrade, and Jesús Tapia. 2024. Media Consumption in Ecuador: Are Ultramediaciones Developing for Everyone? Dordrecht: Atlantis Press International BV, vol. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, Maria, Anjala Krishen, and My Bui. 2020. The Internet of Everything: Implications of Marketing Analytics from a Consumer Policy Perspective. Journal of Consumer Marketing 37: 675–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Barbara J., and Edward F. McQuarrie. 2002. The Development, Change, and Transformation of Rhetorical Style in Magazine Advertisements 1954–1999. Journal of Advertising 31: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollay, Richard W. 1986. The Distorted Mirror: Reflections on the Unintended Consequences of Advertising. Journal of Marketing 50: 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Jef I., and Catharine M. Curran. 2002. Oracles on ‘Advertising’: Searching for a Definition. Journal of Advertising 31: 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, Daniel. 2024. 69 Mobile Internet Traffic Statistics For 2024 (Worldwide Usage)Le. Demandsage. Available online: https://www.demandsage.com/mobile-internet-traffic/ (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Schultz, Don E., Martin P. Block, and Kaylan Raman. 2012. Understanding Consumer-Created Media Synergy. Journal of Marketing Communications 18: 173–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, Kim Bartel, and Caitlin Doherty. 2001. Re-Weaving the Web: Integrating Print and Online Communications. Journal of Interactive Marketing 15: 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewale, Rohit. 2024. Internet User Statistics in 2024—(Global Demographics). Demandsage. Available online: https://www.demandsage.com/internet-user-statistics/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Simon, Jean Paul, and Marc Bogdanowicz. 2012. The Digital Shift in the Media and Content Industries. Policy Brief. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, Kristin, Matt Kammer-Kerwick, Allison Auchter, Hyeseung Elizabeth Koh, Mary Elizabeth Dunn, and Isabella Cunningham. 2019. Examining Digital Video Advertising (DVA) Effectiveness: The Role of Product Category, Product Involvement, and Device. European Journal of Marketing 53: 2451–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, Jonathan. 2008. Why Is the Google Algorithm So Important? Available online: https://computer.howstuffworks.com/google-algorithm1.htm (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Tamborini, Ron, Nicholas David Bowman, Allison Eden, Matthew Grizzard, and Ashley Organ. 2010. Définir l’appréciation Des Médias Comme Étant La Satisfaction de Besoins Intrinsèques. Journal of Communication 60: 758–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Charles R. 2009. The Six Principles of Digital Advertising. International Journal of Advertising 28: 411–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Think with Google. 2020. YouTube Ads Leaderboard. Available online: https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/advertising-channels/video/leaderboards/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Truong, Yann, Rod McColl, and Philip J. Kitchen. 2010. Uncovering the Relationships between Aspirations and Luxury Brand Preference. Journal of Product & Brand Management 19: 346–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turley, Louis W., and Scott W. Kelley. 1997. A Comparison of Advertising Content: Business to Business versus Consumer Services. Journal of Advertising 26: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Neira, Concepción, Yogesh K. Dwivedi, and Zaira Camoiras-Rodriguez. 2023. Social Media Marketing System: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Validation. Internet Research 33: 1302–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorveld, Hilde A. M. 2011. Media Multitasking and the Effectiveness of Combining Online and Radio Advertising. Computers in Human Behavior 27: 2200–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorderer, Peter, and Ute Ritterfeld. 2009. Digital Games. In The Sage Handbook of Media Processes and Effects. Edited by Robin L Nabi. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage, pp. 455–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wedel, Michel, Enrique Bigné, and Jie Zhang. 2020. Virtual and Augmented Reality: Advancing Research in Consumer Marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing 37: 443–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock, Jeryl, and Carole Pimblett. 1997. The Standardisation Debate in International Marketing. Journal of Global Marketing 10: 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, Ahmad Bin. 2018. Analyzing the Role of Integrated Marketing Communication: Significance of Incorporation with Social Medias. Fareast International University Journal 1: 38–53. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Major Topics | Most Cited Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Up to 2005 | Customer trust, Internet marketing and advertising, Internet forums and reviews, customer satisfaction and loyalty (eCRM), interactive advertising | Hoffman and Novak (1996); Salomon and Koppelman (1992); Berthon (1996); Alba et al. (1997); Hamill and Gregory (1997); Hamill (1997); Novak et al. (2000); Liu and Arnett (2000); Mobasher et al. (2000); Childers et al. (2001); McKnight and Chervany (2001); Koufaris (2002); Srinivasan et al. (2002); Vander Heijden et al. (2003); Anderson and Srinivasan (2003); Pavlou (2003); Shankar et al. (2003); Corritore et al. (2003); Chen and Dubinsky (2003); Sawhney et al. (2005); Ko et al. (2005) |

| 2006–2010 | Customer trust, e-WOM, m-commerce, co-creation with customers, personalization, rise in online social network groups, online advertising | Chiu et al. (2006); Awad and Krishnan (2006); Gruen et al. (2006); Overby and Lee (2006); Dellarocas (2006); Dellarocas et al. (2007); Litvin et al. (2008); Duan et al. (2008); Mangold and Faulds (2009); Jansen et al. (2009); Valenzuela et al. (2009); Trusov et al. (2009); Ritzer and Jurgenson (2010); Hennig-Thurau et al. (2010); Hoyer et al. 2010) |

| 2011–2015 | Customer engagement, satisfaction, e-WOM, e-branding, e-commerce trust, CRM in social media, personalized advertising, social networks, big data analytics, virtual communities, and generation of co-creative content in social media marketing | Chu and Kim (2011); Hanna et al. (2011); Ye et al. (2011); Moe and Trusov (2011); De Vries et al. (2012); Kim and Ko (2012); Cheung and Thadani (2012); Sashi (2012); Brodie et al. (2013); Goh et al. (2013); Huang and Benyoucef (2013); Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan (2013); Bolton et al. (2013); He et al. (2013); Kim and Park (2013); Filieri and McLeay (2014); Fang et al. (2014); Tucker (2014); Ashley and Tuten (2015); Ngai et al. (2015); Verhoef et al. (2015) |

| 2016–2020 | Social media marketing, digital branding, social media content using AI techniques, augmented reality and video advertising, celebrity or influencer endorsements in advertising, big data and data mining | Bello-Orgaz et al. (2016); BabicRosario et al. (2016); Salehan and Kim (2016); Hsiao et al. (2016); Akter and Wamba (2016); Chen et al. (2017); Xiang et al. (2017); Felix et al. (2017); Khan (2017); Kannan and Li (2017); Kapoor et al. (2018); Stieglitz et al. (2018); Kamboj et al. (2018); Kleis Nielsen and Ganter (2018); Shareef et al. (2019); Yen and Tang (2019); Arora and Sanni (2019); Martins et al. (2019) |

| Popular Foreign Ads | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Category | Sub-Category | Brands | % |

| Electronic products | Duracell, Samsung, Apple, Amazon, OPPO F7, Motorola, Playstation, Nintendo, T-Mobile | 20 | |

| Entertainment–Culture–Philanthropy | Gaming | Super Cell, Pokemon, Lego | 20 |

| Media | Youtube Music, FanPage.it, Google, Netflix, HBO, Disney+, Hulu, Amazon Prime, Apple TV+, Discovery+, Quibi, Peacock | ||

| NGO’s | Ad Council, IRC | ||

| Alcoholic beverages | Budweiser, Heineken, Mtn-Dew, Stella Artois | 12 | |

| Personal Hygiene | Always, Procter & Gamble, Miss Dior, Durex, Dove, Gillette, Old Spice | 12 | |

| Sports Equipment | Nike, Adidas, Reebok | 12 | |

| Food products | Knorr, Gatorade, Skittles, Oreo, Doritos | 10 | |

| Automotive products | Hyundai, Kia, Audi, GMC, Toyota | 8 | |

| Home products | Mr Clean, Bosch | 4 | |

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digitized TV commercials | 50% | 50% | 60% | 50% | 50% | 40% | 50% | 30% | 20% |

| Digital versions of TV commercials | 50% | 30% | 30% | 30% | 40% | 30% | 30% | 30% | 30% |

| Digital Ads | 0% | 20% | 10% | 20% | 10% | 30% | 20% | 40% | 50% |

| Ad length (in min.) | 2.00 | 2.10 | 2.00 | 2.05 | 2.10 | 2.10 | 3.05 | 2.15 | 2.20 |

| Popular Foreign Ads | ||

|---|---|---|

| Advertising Appeal | Number of Ads | % |

| Enjoyment | 57 | 16 |

| Productivity | 43 | 12 |

| Adventure | 43 | 12 |

| Independence | 43 | 12 |

| Sexuality | 29 | 8 |

| Affiliation | 29 | 8 |

| Modern | 22 | 6 |

| Status | 14 | 4 |

| Technological | 14 | 4 |

| Community | 14 | 4 |

| Magic | 14 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garganas, O. Digital Video Advertising: Breakthrough or Extension of TV Advertising in the New Digital Media Landscape? Journal. Media 2024, 5, 749-765. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020049

Garganas O. Digital Video Advertising: Breakthrough or Extension of TV Advertising in the New Digital Media Landscape? Journalism and Media. 2024; 5(2):749-765. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020049

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarganas, Odysseas. 2024. "Digital Video Advertising: Breakthrough or Extension of TV Advertising in the New Digital Media Landscape?" Journalism and Media 5, no. 2: 749-765. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020049

APA StyleGarganas, O. (2024). Digital Video Advertising: Breakthrough or Extension of TV Advertising in the New Digital Media Landscape? Journalism and Media, 5(2), 749-765. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020049