Abstract

Digitalisation has redefined both media events and monarchical communication by enabling the diverse and critical participation of journalists and citizens. Media events that were once dominated by official narratives are now subject to multiple real-time transformations, with competing storylines emerging. This study examines the treatment of two monarchical figures (Queen Elizabeth II and King Juan Carlos I) during “the first major state funeral in the digital age” when the official invitation to Juan Carlos I generated a debate about his status and sparked curiosity about a potential photo. From an initial collection of 100,000 tweets and 1520 news articles, 187 pieces simultaneously mentioning both monarchs were selected and analysed to compare their treatment. In contrast to the British portrayal linked to professionalism and tradition, the Spanish media—and especially the social networks—immerse Juan Carlos I in controversy. A planned event in which strategic institutional messages were launched serves as an excuse for criticism and polarisation around the monarchy. This confirms that digitalisation has not only altered the way people access and participate but has also redefined the narratives of even the most traditional events. These transformations pose significant challenges to the image management of institutions such as the monarchy.

Keywords:

accountability; media event; monarchy; transmedia stories; coronations; scandals; Twitter (now X) 1. Introduction

1.1. The Transformation of Media Events in the Digital Society

Digitalisation has redefined media events (Dayan and Katz 1992), enabling more active and diverse audience participation (Couldry and Hepp 2018; Einav 2022). Events that were previously dominated by official narratives, as they were broadcast in a controlled manner on television, are now subject to multiple interpretations, transformations, co-creations and critiques in real time (Dottori et al. 2024).

Following a review of articles, Brügger (2022) highlights some changes. Mitu (2016), for example, points to the emergence of user-generated media events on the web, which allow global coverage to be accessible at any time, in contrast to the need to wait for a live television broadcast. Couldry and Hepp (2018) underline the importance of datification and algorithms in its construction, with platforms such as Twitter (now X)1 intertwining with traditional media. Moreover, the multiplication of devices and social media broadcasting has implied a fluctuating dynamic of the “centre” of the event, where multiple perspectives coexist in the transmission and dissemination of content (Einav 2022). But more importantly, evidence suggests that digitisation not only alters how we access and participate, but also how it redefines the structure and narrative of these events (Brügger 2022).

Years ago, Dayan and Katz (1992) divided media events into contests, conquests and coronations. The first includes sporting and political competitions, the second includes exceptional historical achievements (such as the trip to the moon), and the third affects rituals of passage such as weddings or funerals. Additionally, based on their function, media events can be transformative—generating a change in the social context and calling for public support—or restorative—reviving the past and its lost traditions (Coman 2011).

State funerals are restorative coronations. They have been targeted as tools of public diplomacy (Cocera Arias 2023), in which a strategic narrative (Roselle et al. 2014) is used to strengthen the soft power (Nye 1990)2 of a state or institution. Narratives about a country’s history, identities or certain personalities or institutions are appealing, but they are also soft power “assets” that can resonate with individuals’ personal narratives about their identity and values, their communities and their place in the world (Roselle et al. 2014). In such celebrations, traditionally, a media serving the benefiting institution strategically selects, prioritises and presents issues and approaches to the public (McCombs and Shaw 1972; McCombs and Valenzuela 2007), with journalists often adopting a ceremonial and reverential approach in their coverage (Şuţu 2012) eliminating critical dimensions.

The Elizabeth II funeral—a traditional media event—was, nevertheless, the largest digital state funeral, in which Twitter favoured immediacy and ubiquity to the institutional narrative but also fostered an uncontrollable potential autonomy from it. As has been seen in other cases (Salcudean and Muresan 2017), the media, the public and the leaders gathered, generated and disseminated information simultaneously, and while the organisers launched a strategic narrative praising the deceased and explaining the protocol (Estanyol 2022), the platforms and networks allowed messages to be composed and recomposed.

While the effects of transmedia narratives of media events have been studied in events and competitions, they have been little explored in funerals. Thus, Sakaki et al. (2022) analysed the Tokyo Olympics and noted that Twitter introduced new dimensions to the impact of the event, as when it echoed the television rebroadcasts, it united around a ceremony but disunited and polarised around political issues or personalities.

Twitter, a network highly polarised in controversies, allows for an active role in the construction of current affairs (Bastos and Mercea 2019; Jungherr et al. 2017) and seems to be able to interfere in the main plots with critical conversations that have public, media and political repercussions (Tumasjan et al. 2010).

In this framework, it is worth analysing to what extent, in the context of a digital media event, comparisons between royal houses were fostered in networks and media and generated cohesion or polarisation around the monarchy as an institution.

1.2. Monarchies, Communication and Accountability in the Digital Age

The monarchy has historically used the media to build and maintain its public image (Owens 2019). With the advent of social media, this relationship has become complex, as the public can directly interact and comment on the actions and decisions of monarchs.

In the digital age, networks have played the role of indirect control of an institution that straddles the line between accountable and unaccountable (Espiritusanto and Gonzalo 2011), complementing the media (Agbo and Chukwuma 2017; Garrido et al. 2020; Martín-Llaguno et al. 2022) in both the UK and Spain.

The British Royal Family had been the focus of attention in books, articles, media and digital platforms (Parmelee and Greer 2023) for years. Marsden and Marsden (1993) already studied their presence and popularity in American magazines, including the coronation, rituals and attire; Benoit and Brinson (1999) examined Elizabeth II’s speech after the death of Princess Diana, concluding that the strategic approach to communication was essential to enhance the Queen’s image; and Bastin (2009) analysed how films based on the Royal Family have influenced public perception.

But the truth is that before the information society, English monarchs protected themselves through a mutually beneficial relationship with the mainstream media (Elphick 2021). For years, Fleet Street refrained from publishing compromising articles in exchange for controlled access to royal news information (Price 2021). With social media, and especially in the wake of the crisis caused by the death of Diana of Wales, the Royal Family understood that it had to adapt to the new scenario and that it had to constantly broadcast to be in control. Queen Elizabeth II made her first Facebook post in 2010, her first tweet in 2014 and her first Instagram post in 2019. The importance of these media is reflected in the establishment of a protocol and the hiring of a community manager to manage their platforms.

Experts agree that it was the wedding of Prince William and Catherine—the first royal wedding on Twitter—that was the turning point for this institution in the use of new media (Şuţu 2012; Dekavalla 2012; Plunkett 2018)3. From that moment on, a digital strategy was established that has not always succeeded in redirecting narratives. Following Harry and Megan’s break with the royal family, digital platforms—especially Twitter and Instagram—became battlegrounds on issues such as racism, privacy and the role of the media and the monarchy (Clancy and Yelin 2021). At the same time, allegations against Prince Andrew over his links to sex offender Jeffrey Epstein generated outrage and demands for accountability online.

There are similarities and differences with the Spanish monarchy, on whose communication there is a growing body of work (Herrero-Jiménez et al. 2023). To begin with, members of different royal families have been involved in controversial situations that, when publicised, have generated public outrage (Thompson 2001). The peculiarity is that in Spain, the protagonist of the controversies has been King Juan Carlos I, once the highest representative of the institution, and the price of punishment (linked not to the condemnation of justice but to that of public opinion) resulted in his resignation and exile.

Since the end of the dictatorship and the beginning of democracy, until this last decade, the existence of a “journalistic amnesia” (Ramos 2012) with the aim of benefiting the image of the monarchy and accompanying the King’s strategy (Barrera and Zugasti 2003) was suggested. However, Juan Carlos I’s mishaps caused the pact to break down. From 2008 onwards, statements made by Queen Sofia led to scandals being covered in some media (De Pablos et al. 2009), and since then, press coverage of the Emeritus King has multiplied in a biased and polarised way (Herrero-Jiménez et al. 2023).

The Nóos case involving Urdangarin and the Infanta Cristina and Juan Carlos I’s elephant accident in Botswana caused a fall in the surveys of confidence in the monarchy in 2014 (Garrido et al. 2020), which led the institution to its worst reputational crisis, culminating in the abdication of Juan Carlos I (Martín-Llaguno et al. 2022). New technologies and generational change also mean that “the younger public, born and educated in democracy […], who have not lived through the era of the Transition, attach less value than previous generations to the figure of Juan Carlos I and to the monarchical institution itself” (López and Valera 2013).

In this context and with the desire to break ties and open a new era, upon the coronation of Felipe VI, the official profile of the Royal Household on Twitter was created on 21 May 2014. This is part of a new communication strategy, the aim of which is to rely less on traditional media and to control information on the network (Cano-Orón and Llorca-Abad 2017). From the first tweet to the coronation of the new King, the Royal House uses the social network as a complement to its communication strategy (Pulido-Polo et al. 2022), with a discourse that is contrary to that of the media and taking great care over what is published. Since his arrival, an attempt has been made to disassociate Felipe VI from the scandals of the Emeritus King, avoiding joint public appearances and focusing on the qualities of the new King and the Princess of Asturias (García and Flores 2020).

Nevertheless, existing studies suggest that counter information is not very successful from an official account with an impersonal and unidirectional use (Cano-Orón and Llorca-Abad 2017) that is not strategically managed.

1.3. The Object of Study: The Funeral of Elizabeth II

On 19 September 2022, all TV channels in the UK broadcast the funeral of Elizabeth II (Aguilera 2022) using 213 Full HD cameras and 14 OB cameras, according to the BBC (Moore 2022). More than 4 billion viewers in 200 countries followed the event live (Team DF 2022) with a single story focusing on the ceremony. In Spain, and from the official coverage, special programmes were broadcast on public television channels and platforms (La 1, Canal 24 Horas, RNE and RTVE Play) and on private channels (Saiz 2022) with guests and live connections from London and Windsor (RTVE 2022). The Queen’s death officially announced on Twitter, attracted more than 30 million users from all over the world who shared and co-created with journalists the events in London (Editorial Department of LAVOZ 2022).

The funeral—an event of great historical significance, which was broadcast live on television with a global influence (Şuţu 2012) and characterised by its preparation and promotion and by the fact that it breaks the daily schedule and is broadcast on all channels because of its one-off nature—fits perfectly with the concept of a media event.

The death of Elizabeth II and her succession put the monarchy in the global spotlight, indirectly inviting comparisons between royal houses. The state funeral, which brought together more than 500 foreign dignitaries, provided a main narrative (Dioses et al. 2017) centred on the funeral and the exaltation of the deceased. Domínguez-García (2024) analyses the 200 messages published on the official accounts of the British Royal Family on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube from the death of the monarch (8 September 2022) until her funeral (19 September 2022). The author highlights a clear planning of online communication, focused on glossing the figure of the Queen and giving all kinds of details about the funeral. This strategic story receives a great and positive response from digital audiences (something that does not happen with the coronation of Charles III) despite cultural differences on death. Nonetheless, the management of the story is a challenge (Domínguez-García 2024) because, in a digitalised context, the state funeral becomes a transmedia product with parallel plots.

In Spain, the British Royal Household’s invitation to Juan Carlos I, who was facing a lawsuit in London for harassment (Pozas 2022), captured public attention at the time. When the Spanish Royal Household made it clear that the decision to attend or not was Juan Carlos I’s and disassociated itself from his election (Vozpópuli 2022), the public debate was opened because the invitation confirmed, according to the Emeritus King’s defence, that he is still a member of the royal family.

The offer favoured Juan Carlos I’s judicial situation (by considering him a member of the royal family) but opened a controversy, as it contradicted the narrative maintained for years by the Spanish government and monarch. In addition, the funeral was also an opportunity for a public meeting, avoided for months, between the King and his father.

The parallel plot about the “other monarch” that captured the attention of the press, politicians and citizens overlapped with the official plot.

The funeral of Elizabeth II is presented as a natural experiment to observe how the hyperdigital society (Martín-Llaguno et al. 2022) constructs agendas in the context of a media event. The aim of this paper is to compare the official, public and published narratives surrounding two central figures of modern monarchies (Juan Carlos I and Elizabeth II). More specifically, it seeks to identify the issues and aspects prioritised by institutions, media and tweeters.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to achieve our objective, we carried out an analysis of tweets and journalistic pieces. Twitter was chosen over other networks because of its relevance in the dissemination of official messages—46% of the total number of tweets broadcast on networks at the funeral for the British royal family (Domínguez-García 2024)—because of its polarisation and capacity to generate public conversations in real time (Barberá et al. 2015) and because of its proven role in the accountability of the monarchy (Harju 2021; Martín-Llaguno et al. 2022).

2.1. Analysis of Population and Sample

2.1.1. Tweets

We started by examining the official accounts of the Spanish Royal House, the government and the president of Spain (@CasaReal, @desdemoncloa and @sanchezcastejon) with Twitter’s advanced search tool to ensure an accurate representation of the institutional narratives in Spain about the state funeral.

We then collected 100,000 tweets (50,000 about Elizabeth II and 50,000 about Juan Carlos I, the maximum allowed for free download by the old Twitter) during the early morning of 19 September using specific keywords “Isabel II”, “Juan Carlos I” or “Rey emérito” written in Spanish (“Elizabeth II”, “Juan Carlos I” and “Emeritus King” in English). To do so, we used the SocioViz tool, a social media analysis software that uses metrics and algorithms from social network analysis to generate reports with relevant data, such as tweets and retweets, graphs of most active users, hashtags and frequent terms.

From the initial download, which is used for the descriptive analysis, the 81 original texts (disseminated in 1045 tweets) that speak simultaneously of both monarchs, i.e., that include mentions of both Elizabeth II and the Emeritus King or King Juan Carlos, were selected.

2.1.2. Journalistic Pieces

For news analysis, we used Dow Jones’ international, corporate and commercial database, Factiva Data Base, which includes some 35,000 news sources from 200 countries in 26 languages, including newspapers, magazines, images and more than 400 news agencies. For our research, we collected information on the media presence of “Juan Carlos I” or “Rey Emérito” (160 news items) and “Isabel II” (1360 news items) in the articles published on 18 and 19 September 2022 in Spanish, both in the headlines and in the full content of the pieces. With the same procedure used for the tweets, we then searched for texts containing both terms in the same period, obtaining 106 journalistic pieces from 49 different newspapers. The study focuses on analysing these texts to assess the media coverage of both monarchs during that event.

2.2. Content Analysis

With the 106 news items and 81 texts disseminated in 1045 tweets mentioning Elizabeth II and King Juan Carlos or Emeritus King, an exploratory analysis was performed using MAXQDA software (2022 version) to order and identify categories of analysis (themes, sub-themes, aspects…). Based on this initial organisation, a protocol for content analysis with 20 variables was developed. This coding system made it possible to measure the mentions (prominence in the agendas), the substantive dimension with which the two monarchs were presented (position on problems, qualifications and personality—second level) and the affective dimensions (positive, negative or neutral) generated by Juan Carlos I and Elizabeth II both on social networks and in the media.

Two trained coders conducted a manual coding of the texts, with an inter-coding Kappa index of 0.92 and an intra-coding Kappa index of 0.93. These data are used for the descriptive analysis, for the correlation with the volume of tweets and for the interpretation of the frames, which was carried out with SPSS 26.

3. Results

3.1. Institutional Positions in Spain

Figure 1 shows the tweets published by the Spanish Royal Family after the death of Elizabeth II. Through this channel and on the web, condolences were expressed to the Royal Family and the British people, including a telegram that Felipe VI sent to the Prince of Wales at the time. It also provided photos of the King and Queen of Spain with Elizabeth II, underlining the British monarch’s “dignity, sense of duty and courage” and posted a video of Felipe VI expressing his condolences from an event in Seville. The story focused on the death and praised the character (in line with the strategic story).

Figure 1.

Tweets posted by the Spanish Royal House after the death of Elizabeth II.

Regarding the government, it was the president’s personal profile—and not the @desdelamoncloa account—that conveyed the condolences. Sánchez underlined the “historic role” of the monarch (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The president’s condolences.

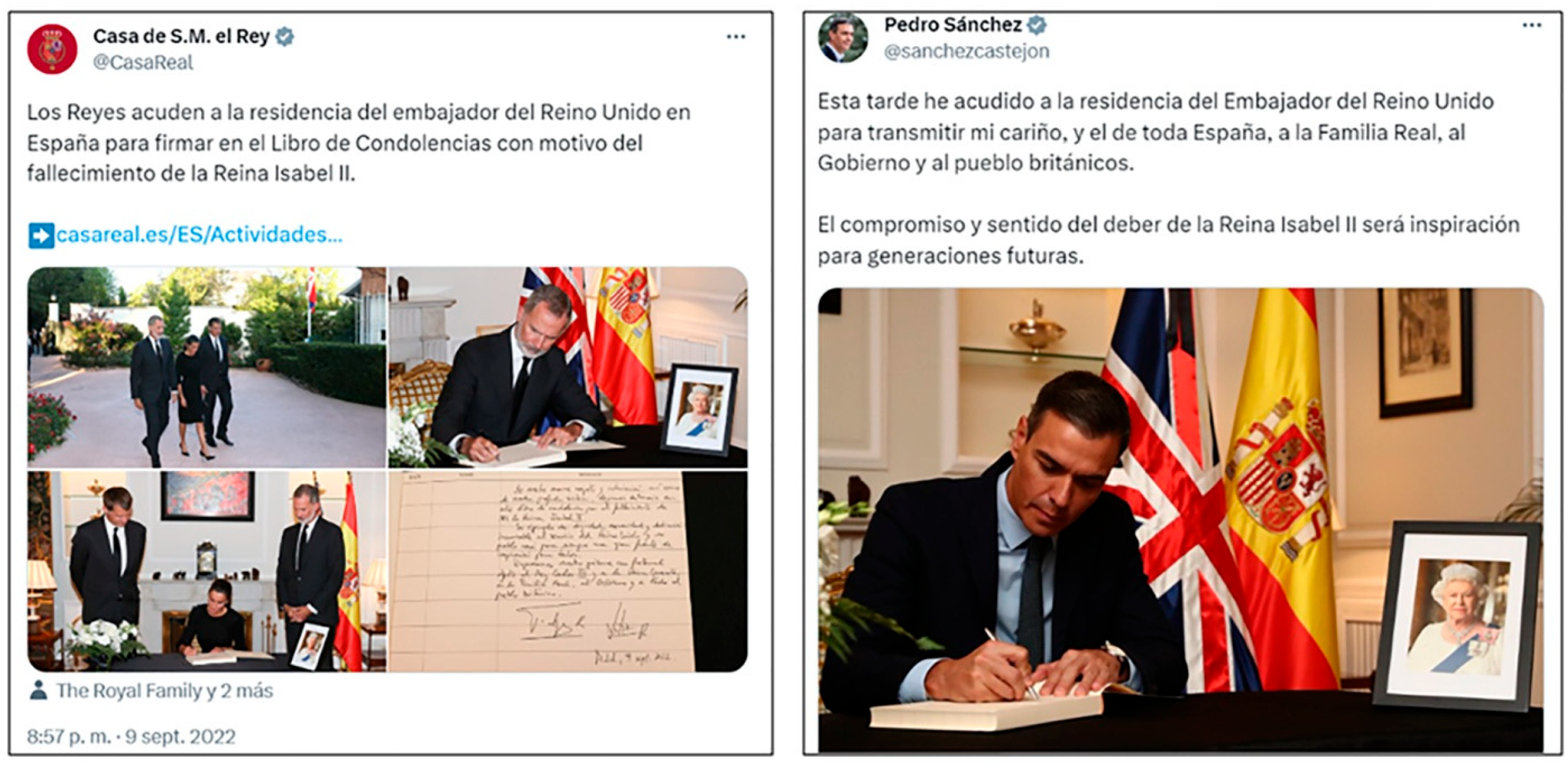

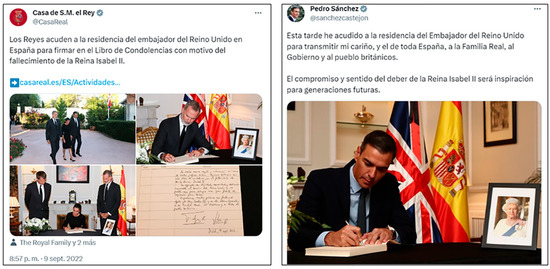

It was also published on the web that both the King and Queen of Spain and the president of the government (Figure 3) went to the UK Ambassador’s residence to sign the Book of Condolence. The president underlined “the Queen’s commitment and sense of duty” with almost identical words to those used previously by the royal household.

Figure 3.

Visit by the King and Queen of Spain and the president to the UK ambassador’s residence.

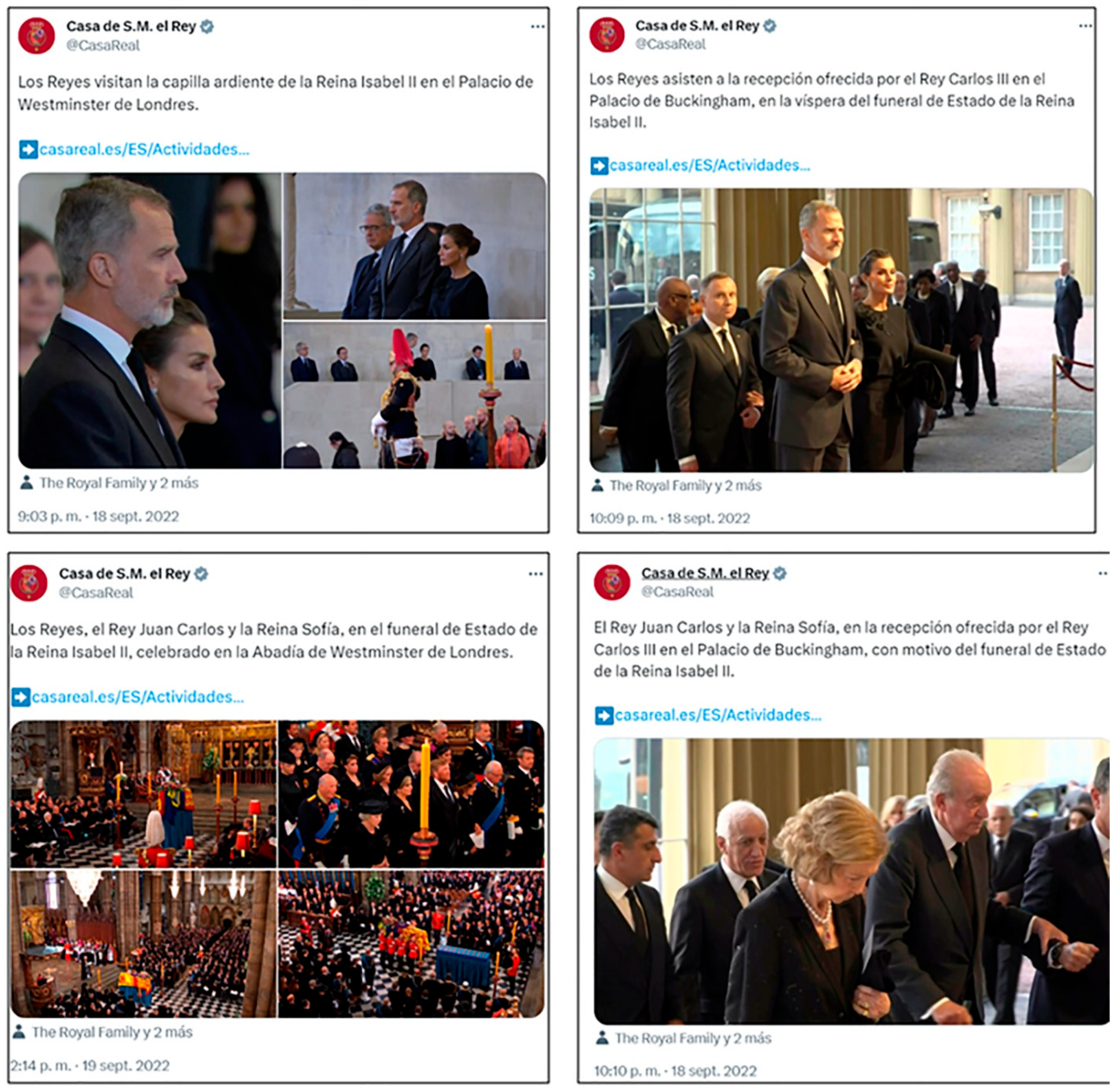

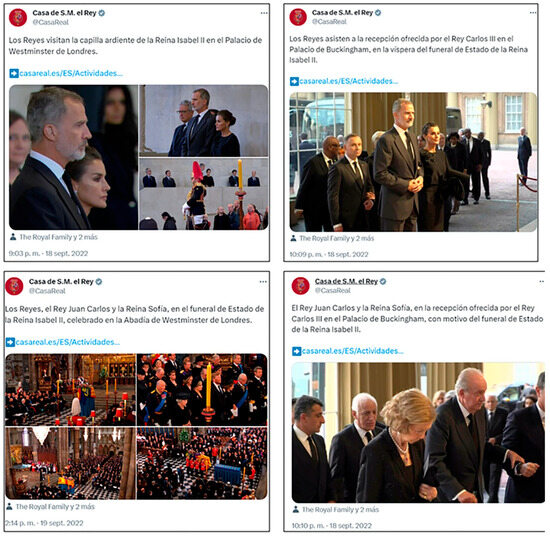

During the funeral, photos of the King and Queen of Spain and consorts at the burial were disseminated without any commentary. It is important to underline that, in line with the strategic account maintained in Spain, @CasaReal showed the emeritus monarchs but not a joint photo with the current monarch. The official account merely reported the presence of the current monarchs and also the Emeritus King Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofia in London (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The King and Queen of Spain, the Emeritus King Juan Carlos I and the Queen Sofia in London.

3.2. Attention Aroused by the Monarchs

The death and funeral of Elizabeth II and the presence of Juan Carlos I became agenda items both on social networks and in the media. The media presence of the Queen of England exceeded that of the emeritus monarch by almost ten times. Spanish newspapers reported 1360 news items about Elizabeth II (compared to 160 on Juan Carlos I) between 18 and 19 September. This difference remained the same on social networks.

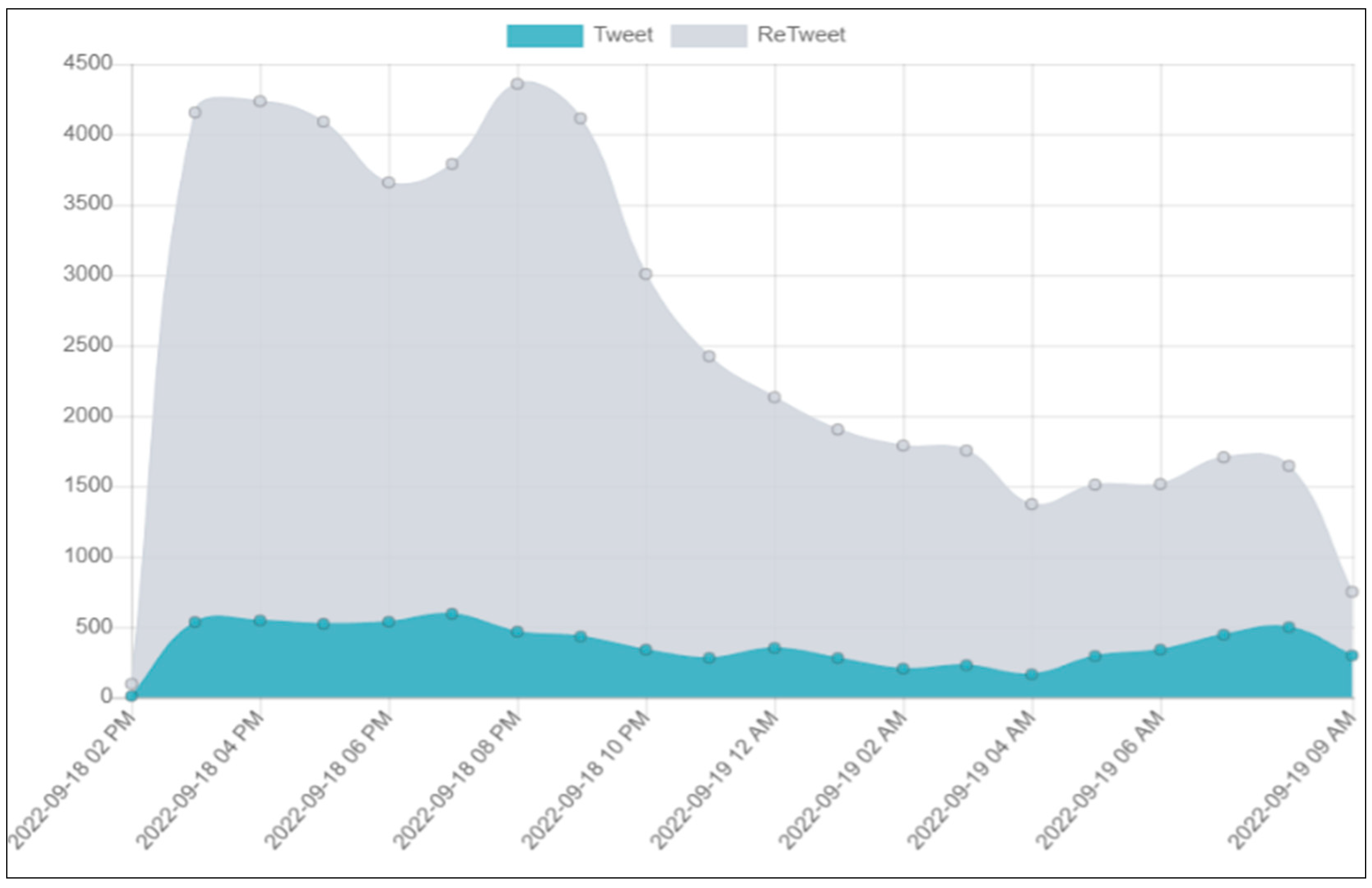

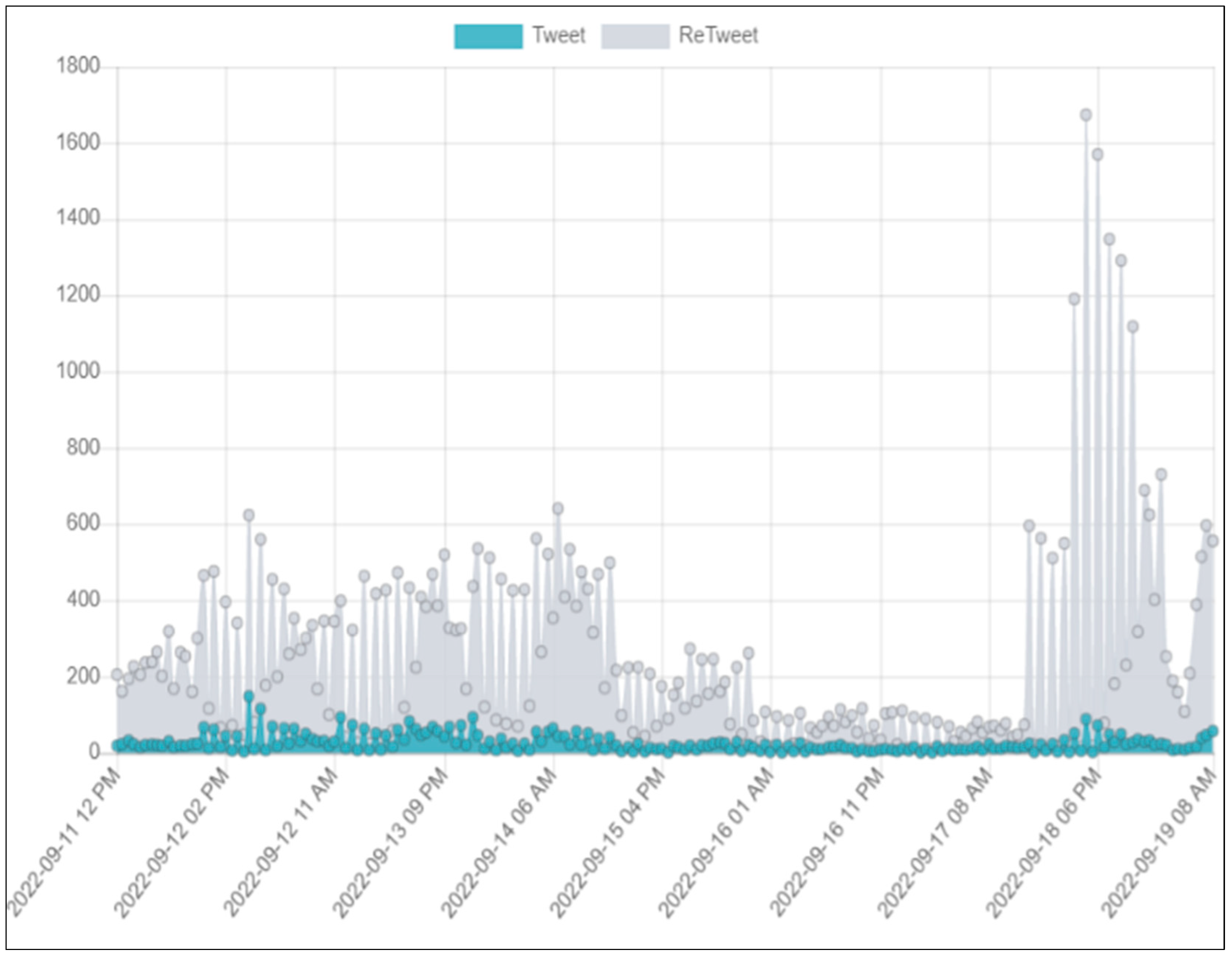

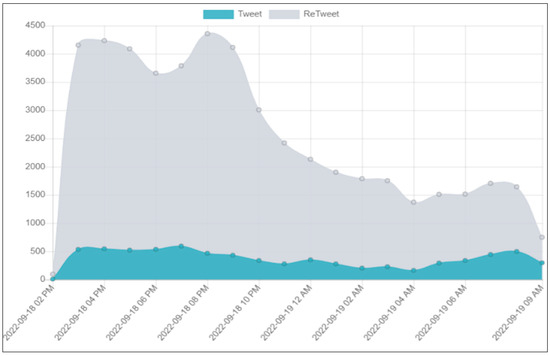

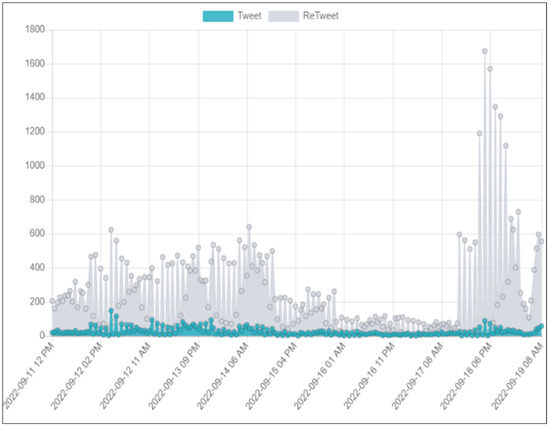

Figure 5 shows 50,000 tweets and retweets in Spanish about Elizabeth II. The peak of attention occurred between 14:00 and 20:00 on 18 September, but the conversation continued into the early hours of the morning. The mentions of the deceased allow us to determine a central narrative about the character. Meanwhile, the 50,000 tweets and retweets about Juan Carlos I from 11 to 19 September extended the time frame because, as expected, there was less conversation than about Elizabeth II, although it increased on 18 and 19 September, when the funeral was held (Figure 6). The sample of tweets shows an important peak of attention on the web on 12 September, when the emeritus’s attendance at the funeral was announced.

Figure 5.

Tweets and retweets mentioning Elizabeth II between 18 and 19 September.

Figure 6.

Tweets and retweets mentioning Juan Carlos I between 18 and 19 September.

In terms of approaches, Table 1 shows the ten most used tags4 in tweets about Elizabeth II and Juan Carlos I during the period analysed. In the case of Elizabeth II (on the left), five were related to her death, and none had a negative connotation. The quantity and plurality reflect the public conversation on the social network. In the case of Juan Carlos I (on the right), the most used was #eliminarlamonarquia (#removethemonarchy in English), followed by #federalyfeminista (#federalandfeminist in English), which clearly reflects the animosity towards the institution. Alongside these, there were two positive hashtags indicating a high degree of polarisation in the conversation: #salvaralrey and #donjuancarlosmerepresenta (#savetheking and #donjuancarlosrepresentsme in English).

Table 1.

The 10 most used tags in tweets mentioning Elizabeth II and Juan Carlos I.

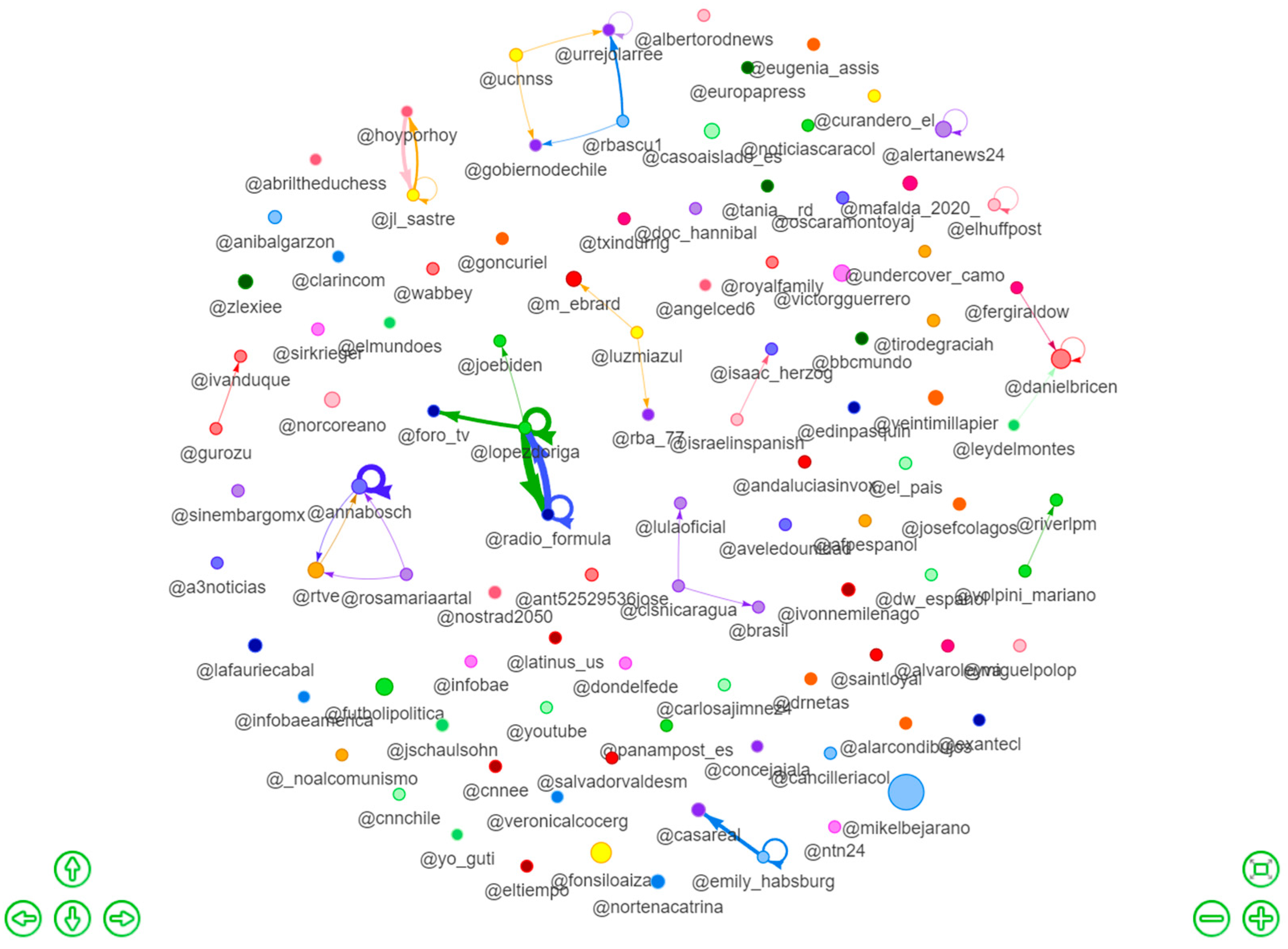

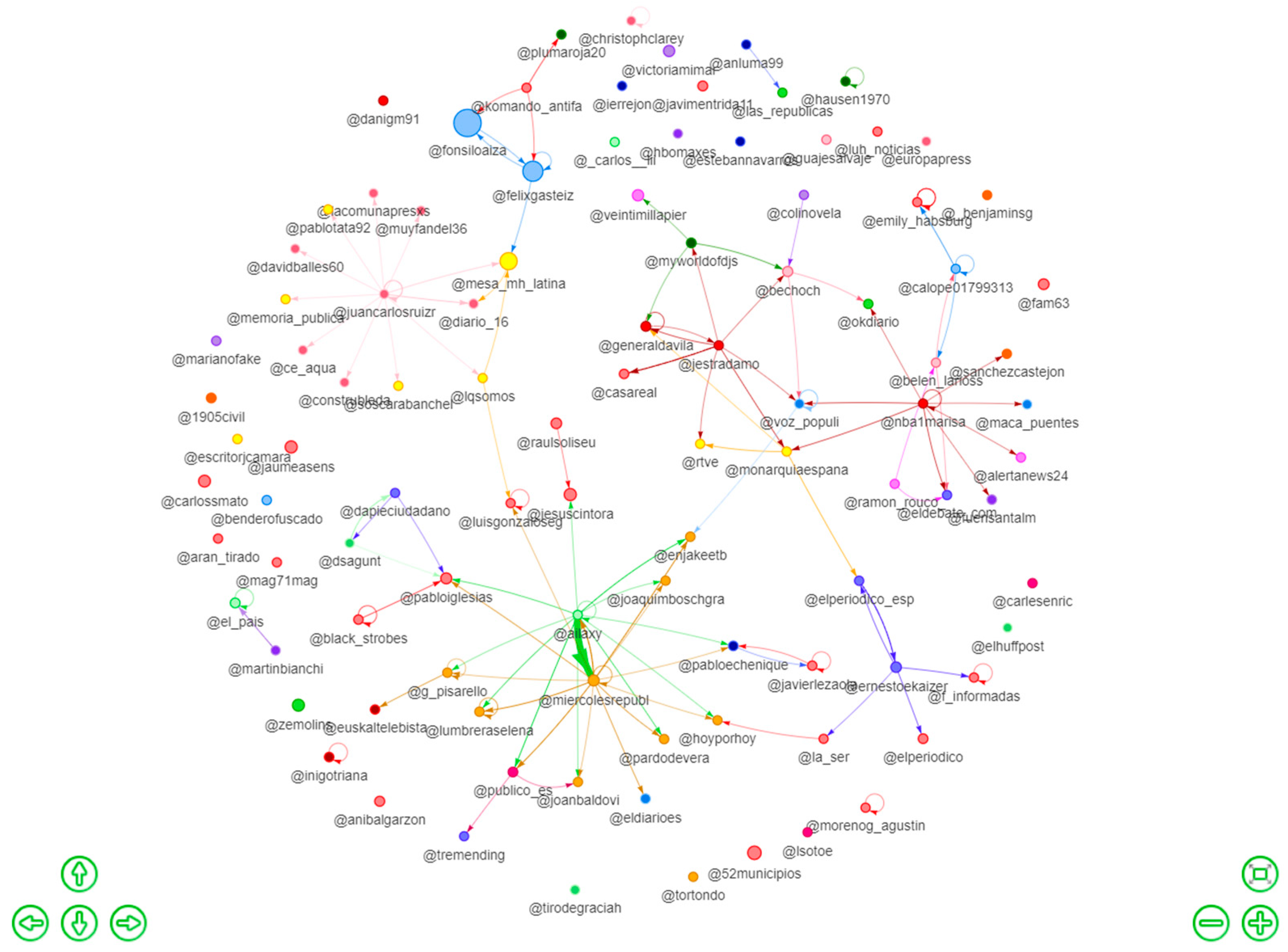

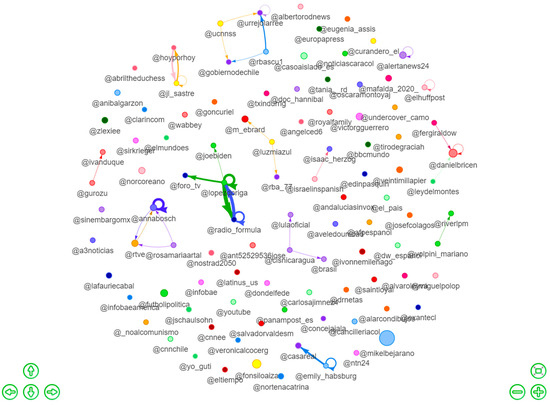

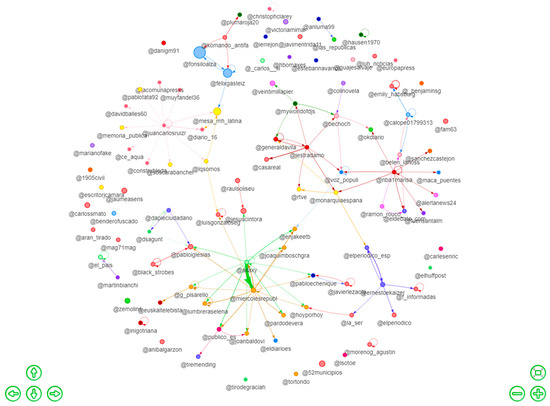

Figure 7 and Figure 8 present the most active users on Twitter, mentioning Elizabeth II and Juan Carlos. In the first case, as can be seen, there were no strong connections between them. Media accounts such as RTVE and El Mundo are the most prominent, along with other personal accounts and those of politicians such as Joe Biden, president of the United States. However, in the case of Juan Carlos I, unlike Elizabeth II, we did find established plots and networks which reflect the polarisation around the figure. Thus, some are linked to Republican users—@miercolesrepublicano, @jesuscintora, @allazy, @joaquinbosh, @pabloechenique…, connected with a section of the media, @laser, @elperiodico…—and others to monarchists—@gestradamo, @nba1marisa, @vozpopuli and @eldebate.

Figure 7.

Most active users mentioning Elizabeth II.

Figure 8.

Most active users mentioning Juan Carlos I.

3.3. Speeches Mentioning Both Protagonists: Substantive and Affective Frames of Elizabeth II and Juan Carlos I

The analysis of the narratives about Elizabeth II and Juan Carlos I revealed divergences in terms of content and tone about both monarchs.

Table 2 shows significant differences (χ2 = 40.596; Sig. = 0.000) between the mentions of the protagonists in the texts. Based on texts that mention both monarchs in the media (especially in the body of the information), Juan Carlos I was the protagonist of the text (42.50%), almost twice as much as Queen Elizabeth (23.6%). On Twitter, the Spanish monarch’s prominence (33.30%) was eight times greater (4.90%).

Table 2.

Text protagonist: tweets vs. news (% of publication).

Unlike in the media, on Twitter, special attention was paid to the duo Felipe VI and Juan Carlos I (17.30% vs. 3.80% in the press) and to the duo Juan Carlos and Sofia (12.30% vs. 0.90% in the press). This fact underlines the interest in the meetings among Internet users and the interest in decoupling past and present in the media.

Along the same lines, Table 3 shows the significant differences (χ2 = 21.177; Sig. = 0.002) in the topics covered. The presence of the Spanish Royal Family at the funeral, with 67.9% of the tweets and 40.6% of the texts, was the most frequent topic. However, the conventional media focused significantly more than the social network on the central story, the funeral of Elizabeth II (33% of news versus 8.6% of tweets).

Table 3.

Main topic of the text: tweets vs. news (% of publication).

There were also noteworthy differences (χ2 = 30.35; Sig. = 0.007) in the subtopics covered on Twitter and in the press (see Table 4). Newspapers focused on the funeral and its guests (14.2%), the funeral in general or the reunion of father and son (10.4% each). Nevertheless, tweeters were mostly interested in the reunion of Juan Carlos (21.9%) with either Felipe (19.8%) or Sofia (13.6%).

Table 4.

Text subtopic: tweets vs. news (% of publication).

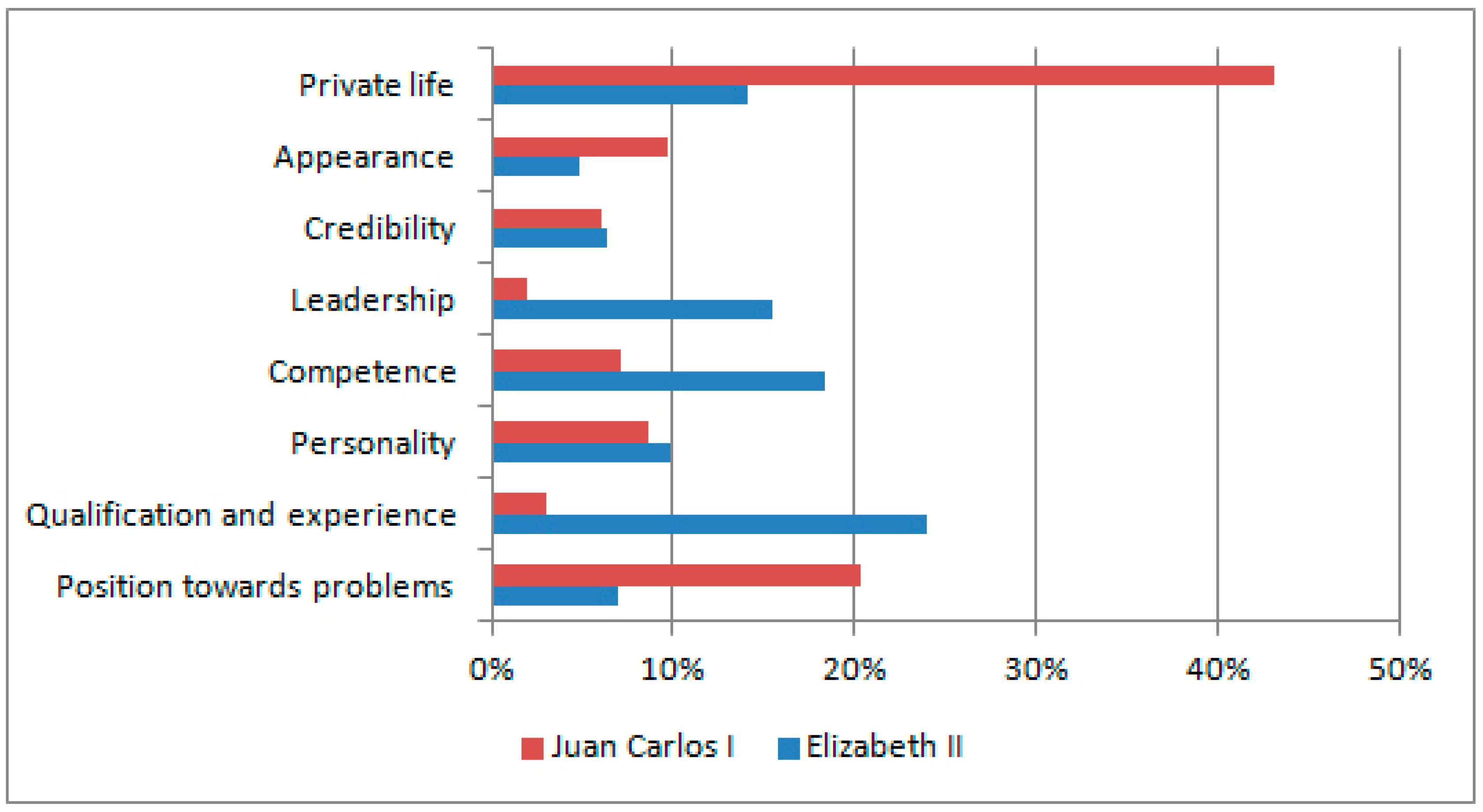

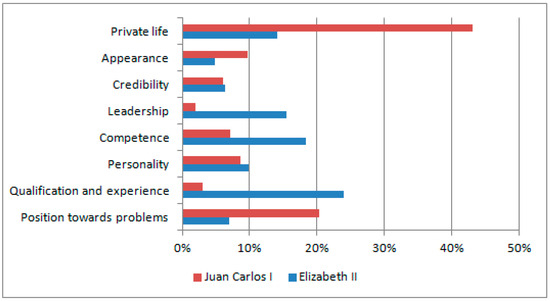

Moreover, while the emeritus was framed in terms of his private life and his position in the face of problems such as corruption, the British were portrayed through the prism of her qualifications and experience (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Frames with which Elizabeth II and Juan Carlos I were defined.

Mentions of Elizabeth II tended to focus on her long service and her role as a symbol of stability and continuity for the United Kingdom. In contrast, narratives about Juan Carlos I often highlighted more controversial aspects, including the judicial investigations that have affected his reputation in recent years.

The discourses varied in the media and on social networks. Internet users were more interested in the private life of Elizabeth II (42.9%), barely touched by the press, and journalists were especially interested in her qualifications and experience (25.6%), in line with what the official agendas had emphasised. It is interesting to note that both media avoided mentioning the Queen’s physical appearance (Table 5).

Table 5.

How Elizabeth II was portrayed (% of publication).

As for the emeritus, both the press (46.0%) and Twitter users (36.7%) were interested in his private life. In addition, Internet users focused on the Spanish monarch’s (in)ability to deal with problems, especially corruption (28.3%). The physical deterioration of the Emeritus King was also mentioned both on Twitter and in the press (10.0% and 9.5%, respectively) (Table 6).

Table 6.

How Juan Carlos I was portrayed (% of publication).

Finally, differences were observed in the affective evaluation of the monarchs (χ2 = 16.9; Sig. = 0.009)5. With the Queen of England, there was no polarisation on Twitter and very little in the press. All mentions of Elizabeth II on the social network were neutral, while in the news there was a 15.4% positive tone and 7.7% negative. The case of Juan Carlos is different, for whom the network was synonymous with criticism (there were no positive mentions in the tweets: 70.4% were neutral, but 25.4% were negative. In the press, however, the situation is even worse: there were 50.7% neutral mentions, 34.3% negative and 4.5% positive. The press showed greater affective polarisation and greater criticism of the emeritus than the social networks (Table 7).

Table 7.

Protagonist and tone of the texts.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The results suggest that digitalisation has transformed the way in which media narratives are constructed and disseminated in events such as state funerals. As a coronation-type restorative media event, that of Elizabeth II captured the attention of newspapers and networks that, in effect, conveyed an account of the Queen’s funeral with a reverential tone and little criticism. Nonetheless, the occasion of the invitation to Juan Carlos I was also used to scrutinise the monarchy and the Emeritus King of Spain.

The participation of users on Twitter allows institutional discourses to be reformulated in real time. This phenomenon can be seen in the contrast between the presentation of the monarchs by the media and social networks: Elizabeth II, associated with professionalism and tradition; Juan Carlos I, involved in controversies and personal and physical dimensions. These facts align with the theories of Brügger (2022) and Dottori et al. (2024) on the multiplicity of interpretations and co-creation of content in the digital age. Media events are no longer monolithic but include multiple plots and voices, as suggested by Couldry and Hepp (2018).

The funeral of Elizabeth II kept part of the traditional dimension of the media events and gathered attention around a ceremony, but it also served as an alibi to polarise issues (the monarchy in Spain) and public figures (in this case, Juan Carlos I). Thus, in parallel to the narrative about the funeral, a conversation was constructed that is aligned with the supervisory role of non-responsible institutions and that reflects the criticism and polarisation regarding the monarchy in Spain in general and Juan Carlos I in particular (Martín-Llaguno et al. 2022). The divisive nature of digital communication is confirmed (Bennett and Segerberg 2012; Smith et al. 2014): the participatory and real-time dimension of digitalisation introduces new layers of public and critical interaction and a relative loss of control of the narrative over media events, echoing Sakaki et al. (2022).

The democratisation of communication has made room for a diversity of opinions and a multidimensional focus: as Brügger (2022) pointed out, in this case in Spain, digitalisation has not only altered the ways of participating but has also redefined the narrative of the event.

The derivation is that the instrument, considered a potential “asset” of soft power and public diplomacy (Cocera Arias 2023), has been bivalent in Spain for the monarchy as an institution: the personal narratives, values and identity of the British monarch have been positive, but have been counterbalanced by those issued about the emeritus and the questioning of the official narrative. Further work could analyse the final effects of this dichotomy on the perception of the monarchy.

The changes introduced by digitalisation present both opportunities and challenges for institutional image management. The British Royal House has given a modern image by using social networks to convey messages ubiquitously. In the Spanish case, the Royal House and the government have also relied on Twitter for their strategic narrative. In a restrained manner, they limited themselves to launching brief tweets with laudatory messages about the deceased, trying to avoid the problem of the meeting between the monarchs. However, none of these controlled messages has managed to avoid the morbidity of the invitation to the emeritus in the media and Internet users.

This paper aimed to provide information to better understand how the control that was once exercised over the narrative in media events has been diluted. Twitter has emerged as a key platform in the construction of the agenda of events, and even in acts as ceremonial as a funeral, it is able to polarise. From a practical perspective, the results suggest that institutions need to develop adaptive communication strategies to navigate a digital environment.

The exploratory study has some limitations. To begin with, it focuses on a single event, with a comparison with a single royal household in a single language. The non-inclusion in the sample of English texts excludes messages that may have been delivered by Elizabeth II’s subjects, which would need to be studied.

Much remains to be explored about coronations in the digital age, for example, the accessibility (geographically and temporally) to the central story across different platforms (How and when are these events consumed? Are they consulted synchronously or asynchronously?); or the role of datification and algorithms in the dissemination of the message. It is also interesting to analyse when and where broadcast “hubs” are built globally.

Our humble findings offer an initial basis for future studies that delve deeper into the generation and effects of transmedia content in this context. Further challenges remain for comparative research between different monarchies and comparative longitudinal analyses that could provide insights into the changing dynamics of public opinion, accountability and different types of media events and monarchy in the digital age.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.-L.; methodology, M.M.-L.; validation, M.M.-L.; formal analysis, M.M.-L. and L.G.-A.; investigation, M.M.-L., M.N.-B., R.B. and L.G.-A.; resources, M.M.-L. and M.N.-B.; data curation, M.M.-L., M.N.-B. and L.G.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.-L.; writing—review and editing, M.N.-B. and R.B.; visualization, M.M.-L., M.N.-B., R.B. and L.G.-A.; supervision, M.M.-L.; project administration, M.M.-L. and R.B.; funding acquisition, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades of Spain, grant number PID2019-105285GB-100 (01-06-2020 to 29-02-2024). The funded research was titled “Los efectos de la información política sobre las percepciones y actitudes implícitas de la ciudadanía y los/las periodistas ante la corrupción” (Efippaic).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Throughout this paper, we refer to Twitter (now X) as “Twitter”, given its continued recognition under this name during the event period. |

| 2 | According to Nye (1990), who coined the term in the late 1980s, “soft power” simply means the ability to “convince or persuade others to follow your lead, to want what you want, rather than coercing, rewarding or deceiving them”. |

| 3 | It had already marked a significant shift in the communication strategies of the British Royal Family, which announced the engagement on the official Twitter account (Chambers 2018), created a website (El Observador 2011) and an official YouTube channel of the monarchy (The Royal Channel) dedicated to the event. |

| 4 | In Table 1, where the hashtags are listed, some, such as #gta6 (Grand Theft Auto 6) or #afp, are used due to the overlap with topics or events that occurred at the time, sharing tags with the trending topic of the Queen’s death. Although they are not immediately relevant to the discussion, they have been retained due to the selection criteria used for choosing hashtags. |

| 5 | In our tone analysis, both in the news and tweets, the sentiment was evaluated using a manual coding approach based on predefined criteria to identify the affective tone (positive, negative or neutral) with which the monarchs were mentioned. Positive mentions were classified as those explicitly highlighting favourable qualities or expressions of support, negative mentions were those that involved direct criticism or questioning of legitimacy or performance (e.g., references to scandals), and neutral mentions were those that showed no clear inclination or explicit expression. Two trained coders conducted the tone analysis, ensuring that the criteria were applied consistently. |

References

- Agbo, Benedict Obiora, and Okechukwu Chukwuma. 2017. Influence of the new media on the watchdog role of the press in Nigeria. European Scientific Journal 12: 126–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, Sergio. 2022. La monarquía británica convierte el funeral de Isabel II en el mayor espectáculo del mundo. El Español. September 18. Available online: https://www.elespanol.com/mundo/europa/20220919/monarquia-britanica-convierte-funeral-isabel-ii-espectaculo/704179699_0.html (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Barberá, Pablo, John T. Jost, Jonathan Nagler, Joshua A. Tucker, and Richard Bonneau. 2015. Tweeting from left to right: Is online political communication more than an echo chamber? Psychological Science 26: 1531–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, Carlos, and Ricardo Zugasti. 2003. Imagen pública de Cataluña y de Juan Carlos I en su primer viaje como rey en febrero de 1976. Anàlisi. Quaderns de Comunicació i Cultura 30: 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bastin, Giselle. 2009. Filming the ineffable: Biopics of the British royal family. Auto/Biography Studies 24: 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, Marco T., and Dan Mercea. 2019. The Brexit botnet and user-generated hyperpartisan news. Social Science Computer Review 37: 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg. 2012. The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Communication Theory 21: 347–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, William L., and Susan L. Brinson. 1999. Queen Elizabeth’s image repair discourse: Insensitive royal or compassionate queen? Public Relations Review 25: 145–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, Niels. 2022. Media events in an age of the Web and television: Dayan and Katz revisited. Nordic Journal of Media Studies 4: 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Orón, Lorena, and Germán Llorca-Abad. 2017. Análisis del discurso oficial de la Casa Real en Twitter durante el periodo de abdicación del Rey Juan Carlos I y la coronación de Felipe VI. Perspectivas de la Comunicación 10: 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Presley. 2018. Social media coverage: Modern royal weddings. Medium. July 26. Available online: https://medium.com/@presleychambers/social-media-coverage-modern-royal-weddings-85bcc09c23c4 (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Clancy, Laura, and Hannah Yelin. 2021. Monarchy is a feminist issue: Andrew, Meghan and #MeToo era monarchy. Women’s Studies International Forum 84: 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocera Arias, Paula. 2023. Ceremonias funerarias: Una mirada desde el poder blando. Comparativa de los Funerales de Isabel II de Inglaterra, Benedicto XVI y Constantino II de Grecia. Revista Estudios Institucionales: Revista Internacional de Investigación en Instituciones, Ceremonial y Protocolo 10: 245–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coman, Mihai. 2011. Media events—O paradigmă la granița dintre antropologie si științele comunicării. In Media Events—Perspective Teoretice si Studii de Caz. Edited by Mihai Coman. București: Editura Universitătii din București, pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Couldry, Nick, and Andreas Hepp. 2018. The continuing lure of the mediated centre in times of deep mediatization: Media events and its enduring legacy. Media, Culture & Society 40: 114–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, Daniel, and Elihu Katz. 1992. Media Events: The Live Broadcasting of History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dekavalla, Marina. 2012. Constructing the public at the royal wedding. Media, Culture & Society 34: 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pablos, Coello, José Manuel, and Alberto Ardèvol Abreu. 2009. Prensa española y monarquía: El “silencio crítico” se termina. Estudio de caso. Anàlisi: Quaderns de Comunicació i Cultura 39: 237–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dioses, Kelly Robledo, Tomás Atarama Rojas, and Henry Palomino Moreno. 2017. De la comunicación multimedia a la comunicación transmedia: Una revisión teórica sobre las actuales narrativas periodísticas. Estudios Sobre el Mensaje Periodístico 23: 223–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-García, Ricardo. 2024. Estrategias de comunicación digital de la Casa Real británica durante la muerte y los funerales de Estado de Isabel II. Revista Estudios Institucionales: Revista Internacional de Investigación en Instituciones, Ceremonial y Protocolo 11: 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dottori, Mark, Alex Sévigny, and Norm O’Reilly. 2024. Sport public relations: An evolution from media relations to digital image management through co-creational strategy. In Social Media in Sport: Evidence-Based Perspectives. Edited by Gashaw Abeza and Jimmy Sanderson. London: Routledge, pp. 177–94. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Department of LAVOZ. 2022. La muerte de la reina Isabel II rompió varios récords en Twitter. La Voz del Interior. September 22. Available online: https://www.lavoz.com.ar/tecnologia/la-muerte-de-la-reina-isabel-ii-rompio-varios-records-en-twitter/ (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Einav, Gali. 2022. Media reimagined: The impact of COVID-19 on digital media transformation. In Transitioning Media in a Post COVID World: Digital Transformation, Immersive Technologies, and Consumer Behavior. Edited by Gali Einav. Gewerbestrasse: Springer, pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Observador. 2011. Página Web dedicada a la boda de Guillermo y Kate. El Observador. November 10. Available online: https://www.elobservador.com.uy/nota/pagina-web-dedicada-a-la-boda-de-guillermo-y-kate-20114111950 (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Elphick, J. 2021. Princess Margaret: The princess, the gangster and the saucy snaps. In Scandals of the Windsors. Edited by Philippa Grafton. London: Future Publishing Limited, pp. 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Espiritusanto, Óscar, and Paula Gonzalo. 2011. El valor de la participación y el periodismo ciudadano. In Periodismo Ciudadano. Evolución Positiva de la Comunicación. Edited by Óscar Espiritusanto y Paula Gonzalo. Madrid: Fundación Telefónica, pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Estanyol, Elisenda. 2022. Un funeral lleno de ceremonial (y II). COMeIN. Revista de los Estudios de Ciencias de la Información y de la Comunicación 125: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Raúl, and Daniel Flores, dirs. 2020. Leonor: El Futuro de la Monarquía Renovada. Madrid: ¡HOLA! TV and Amazon Prime Video. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, Antonio, M. Antonia Martínez, and Alberto Mora. 2020. Monarquía y opinión pública en España durante la crisis: El desempeño de una institución no responsable bajo estrés. Revista Española de Ciencia Política 52: 121–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju, Oona. 2021. “Of course Kate does Everything Right. We Already Know That”: Middleton and Markle in the British Tabloids and Twitter. Master’s thesis, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland. Available online: https://oulurepo.oulu.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/19296/nbnfioulu-202105187872.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Herrero-Jiménez, Beatriz, Rosa Berganza, and Eva Luisa Gómez Montero. 2023. La monarquía española a examen: Del silencio consensuado de los medios a los enfoques de ataque y defensa en el caso de los escándalos de Juan Carlos I. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 81: 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungherr, Andrea, Harald Schoen, Oliver Posegga, and Pascal Jürgens. 2017. Digital trace data in the study of public opinion: An indicator of attention toward politics rather than political support. Social Science Computer Review 35: 336–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Guillermo, and Lidia Valera. 2013. La información sobre la Monarquía española en los nuevos medios digitales. AdComunica. Revista Científica de Estrategias, Tendencias e Innovación en Comunicación 6: 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, Michael T., and Madonna P. Marsden. 1993. The search for secular divinity: America’s fascination with the Royal Family. Journal of Popular Culture 26: 131–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Llaguno, Marta, Marián Navarro-Beltrá, and Rosa Berganza. 2022. La relación entre la agenda política y la agenda mediática en España: El caso de los escándalos de Juan Carlos I. Ámbitos: Revista Internacional de Comunicación 57: 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, Maxwell, and Donald L. Shaw. 1972. The agenda-setting function of mass media. The Public Opinion Quarterly 36: 176–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, Maxwell, and Sebastián Valenzuela. 2007. The agenda-setting theroy. Cuadernos de Información 20: 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitu, Bianca. 2016. Web 2.0 media events: Barack Obama’s inauguration. In Media Events: A Critical Contemporary Approach. Edited by Bianca Mitu and Stamatis Poulakidakos. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 230–42. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Sam. 2022. BBC praised for aerial shots inside Westminster Abbey during the Queen’s funeral. Yahoo! News. September 19. Available online: https://uk.news.yahoo.com/bbc-aerial-shots-westminster-abbey-queen-funeral-154542489.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAK0b9KBqn9ZXid_DNrwClO5N-fZqN0d7tGNpo7sYVdtcVwjDlLf9yxUiuvQOVubPROS1cO5EQdadM1Kdx6rx5dZjxd4454pERsCwLRZUu87VzKUSueo1QbySWYBnluFmYibtuPlvYKFHYWh9sf9eCQFOtvZ52lwF6UXNG-6IdiBL (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Nye, Joshep S. 1990. Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, Edward. 2019. The Family Firm: Monarchy, Mass Media and the British Public, 1932–53. London: University of London Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parmelee, Sheri, and Clark Greer. 2023. Visual presentation of self by the British royal family on Instagram. Journal for Cultural Research 20: 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunkett, John. 2018. Prince William and Kate Middleton: Get ready for a right royal TV fuss. The Guardian. May 22. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/media/organgrinder/2010/nov/16/william-kate-engagement-tv (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Pozas, Alberto. 2022. Reino Unido abre la única vía para sentar a Juan Carlos I en el banquillo. ElDiario.es. March 25. Available online: https://www.eldiario.es/politica/reino-unido-abre-unica-via-sentar-juan-carlos-i-banquillo_1_8858517.html (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Price, J. 2021. Eduardo, duque de Windsor: La vergüenza familiar. In Scandals of the Windsors. Edited by Philippa Grafton. London: Future Publishing Limited, pp. 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido-Polo, Marta, Gloria Jiménez-Marín, Concha Pérez Curiel, and José Vázquez-González. 2022. Twitter como herramienta de comunicación institucional: La Casa Real Británica y la Casa Real Española en el contexto postpandémico. Revista de Comunicación 21: 225–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Fernando. 2012. Los escándalos de la corona española en la prensa digital y el futuro de la monarquía. De la amnesia y el silencio cómplice al tratamiento exhaustivo de los medios. Razón y Palabra 79: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Roselle, Laura, Alister Miskimmon, and Ben O’Loughlin. 2014. Strategic narrative: A new means to understand soft power. Media, War and Conflict 7: 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RTVE. 2022. RTVE retransmite este lunes en directo el funeral de Estado de Isabel II. RTVE.es. September 19. Available online: https://www.rtve.es/rtve/20220918/rtve-retransmite-este-lunes-directo-funeral-estado-isabel-ii/2402666.shtml?origen=app (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Saiz, David. 2022. Dónde ver por televisión el funeral de Isabel II: Las cadenas se vuelcan con la despedida de la reina de Inglaterra. ElEconomistaes. September 19. Available online: https://www.eleconomista.es/informalia/television/noticias/11950828/09/22/Donde-ver-por-television-el-funeral-de-Isabel-II-las-cadenas-se-vuelcan-con-la-despedida-de-la-reina-de-Inglaterra.html (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Sakaki, Takeshi, Tetsuro Kobayashi, Mitsuo Yoshida, and Fujio Toriumi. 2022. Do media events still unite the host nation’s citizens? The case of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. PLoS ONE 17: e0278911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcudean, Mindora, and Raluca Muresan. 2017. El impacto emocional de los medios tradicionales y los nuevos medios en acontecimientos sociales. Comunicar: Revista Científica Iberoamericana de Comunicación y Educación 25: 109–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Marc A., Lee Rainie, Ben Shneiderman, and Itai Himelboim. 2014. Mapping Twitter topic networks: From polarized crowds to community clusters. Pew Research Internet Project. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/02/20/mapping-twitter-topic-networks-from-polarized-crowds-to-community-clusters/ (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Şuţu, Rodica M. 2012. The role of the new technologies in the coverage of media events. Case study of the royal wedding of Prince William of the United Kingdom and Catherine Middleton. Revista de Comunicare si Marketing 3: 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Team DF. 2022. Reino Unido y el mundo dan el último adiós a la reina Isabel II en un solemne funeral de Estado. Diario Financiero. September 20. Available online: https://www.df.cl/internacional/politica/reino-unido-y-el-mundo-dan-el-ultimo-adios-a-la-reina-isabel-ii-en-un (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Thompson, John B. 2001. Escándalo político: Poder y visibilidad en la era de los medios de comunicación. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica. [Google Scholar]

- Tumasjan, Andranik, Timm Sprenger, Philipp Sandner, and Isabell Welpe. 2010. Predicting elections with Twitter: What 140 characters reveal about political sentiment. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 4: 178–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozpópuli. 2022. Así ha presionado Juan Carlos I a Casa Real para poder acudir al funeral de Isabel II. YouTube Vozpópuli. September 13. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9tvkKRvuKhs (accessed on 1 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).