Abstract

Gender-diverse populations are at a higher risk of experiencing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and social stigma, with a significant impact on both mental and overall health. This systematic review, conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines, included 14 studies published between 2016 and 2024. Observational studies were extracted from MEDLINE, CINAHL, APA PsycInfo, and APA PsycArticles to explore the prevalence of ACEs and their effects on mental and physical health in gender-diverse individuals. Studies were assessed for quality using the AXIS tool. The studies included revealed elevated rates of ACEs, particularly in the form of abuse. ACEs were strongly associated with an increased risk of depression, anxiety, stress-related disorders, and suicidality. Discrimination further amplified these effects, particularly among racial and ethnic minorities, leading to a higher engagement in risky behaviors and poorer physical health outcomes. Protective factors identified included secure attachment, access to gender-affirming care, and strong social support. The findings emphasize the urgent need for trauma-informed and culturally sensitive interventions that address both the immediate and long-term effects of ACEs in gender-diverse populations. Future studies should prioritize longitudinal designs and tailored interventions to meet the healthcare needs of these communities and develop mental health prevention strategies.

1. Introduction

In the 2000s, the term ‘gender diversity’ was predominantly used to describe disparities between female and male individuals in contexts such as professional settings [1]. For example, up to 2008, this term could be encountered reading about the balanced presence of women and men in work teams within public organizations, which was identified as a factor enhancing both performance and well-being [2]. Over time, this term evolved to encompass a broader and more inclusive understanding of gender identities beyond the binary. In this sense, one of its first appearances occurred in an article by nurse and writer Lyn Merryfeather, published in 2011 [3]. Drawing on personal experiences and research, Merryfeather describes how this term began to be adopted primarily to refer to individuals “who do not comfortably identify within the binary of male and female” [3]. This concept followed earlier terms such as ‘gender variance’, ‘Psychological Androgyny’ (focusing on personality traits), and ‘Bigender’, which contributed to the evolving understanding of gender diversity but may not fully capture the experiences and identities recognized today [4]. Among the most common terms found across the literature, we can also find “genderqueer” and “non-binary”. It is important to note that these definitions were often used inconsistently, which has led to some degree of confusion. Given the diverse experiences of gender identities beyond the binary, broader terms such as ‘transgender’ (TG) have proven inadequate in capturing the full spectrum of gender identities.

The concept of gender identity itself has undergone parallel development. In 1969, Stoller argued that sex (meaning sex-assigned-at-birth) and gender (one’s internal sense of gender) were not intrinsically linked [5]. This perspective underscored the need to explore these distinct aspects of human self-perception and laid the groundwork for what is now recognized as gender identity. The latest American Psychological Association (APA) definition of gender identity encompasses, in addition to the terms boy/man/male and girl/woman/female, categories such as “genderqueer”, “gender-fluid”, and “gender neutral” as potential expressions of one’s gender. These experiences are recognized as independent of correspondence to sex assigned at birth or primary and secondary sexual characteristics [6]. Currently, the term ‘gender diverse’ is increasingly used to offer more inclusive language, encompassing identities described by the APA as existing beyond the male–female binary [4].

Generally, between 1% and nearly 3% of young people identify as gender-diverse [7], while 0.6% of Americans identify as TG, a percentage consistent with European data [8]. Despite the significant number of gender-diverse individuals, substantial progress in their recognition (e.g., the legal acknowledgment of non-binary identities and the adoption of the singular “they” in some countries), and greater social acceptance of TG individuals, research in psychology and psychiatry still appears to be lagging [7]. According to a 2020 article published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, exploring this field may offer an opportunity to broaden our understanding of gender. Shifting the focus to the nuanced dimensions of gender experiences among non-binary individuals also encourages the exploration of the potential multidimensionality of gender experiences among cisgender (CG) individuals [7]. Alternatives to a binary framework, such as a spectrum of gender experiences between the two sexes, could be explored to deepen our understanding and ultimately reduce prejudice and discrimination [7].

Nevertheless, the relation between gender-diverse individuals and society is crucial in addressing the needs of these minorities. A relevant work that enabled the exploration of the experiences of TG and gender-diverse individuals in the United States is represented by “The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey”. The authors showed that approximately 50% of the participants had experienced anti-transgender harassment in the previous year. TG individuals were found to be exposed to both economic and social fragility compared to the general United States population. Moreover, one in four participants experienced family rejection because of their gender identity, with evidence linking it to increased suicidality, homelessness, and involvement in sex work [9]. Much of the recent information on transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) individuals comes from the latter study. Undeniably, addressing both physical and mental health in gender minorities has proven to be a central focus in contemporary discourse. According to a secondary analysis stemming from “The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey”, gender-affirming surgeries can improve mental health outcomes, such as reducing past-month psychological distress and suicidal ideation [10]. Moreover, another study highlighted that discrimination is a critical factor contributing to an increased risk of suicidal ideation, psychological distress, substance use, and past-year HIV testing. This study also noted that gender affirmation has a significant moderating and protective effect against the impact of discrimination [11]. Thus, belonging to a gender minority has significant implications for mental health, presenting substantial opportunities for dedicated healthcare interventions.

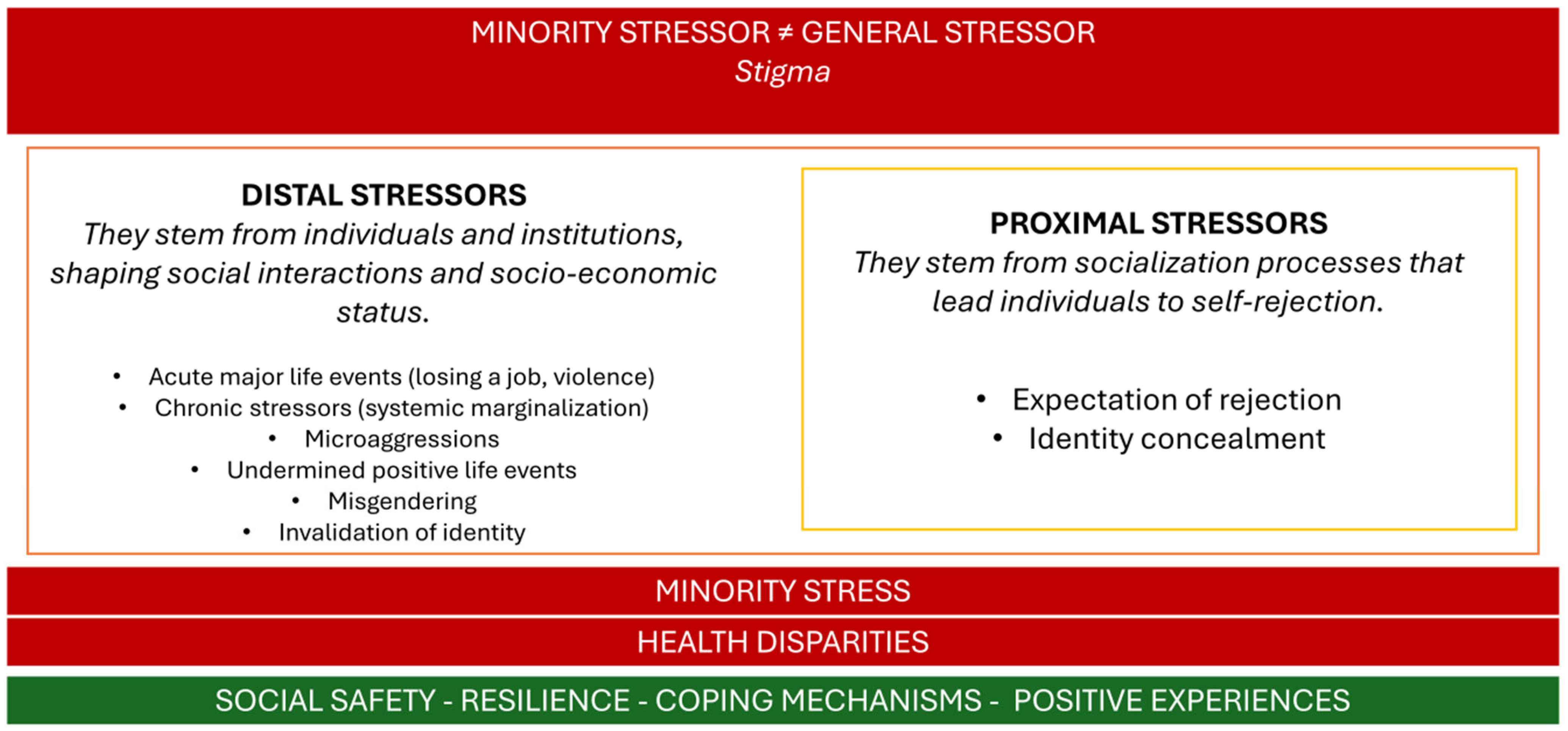

To better understand mental health in gender and sexual minorities, we can adopt the Minority Stress Theory, first described by Ilan H. Meyer in 2003 by integrating different sociological and social psychological theories. The author underscored the increased prevalence of mental disorders among sexual minorities, linking it to the social stress they experience [12]. The article emphasizes the crucial role of an individual’s perceived ’fit’ within society, in addition to personal stressors, in influencing overall health. Thus, this theoretical framework can also be easily applied to gender minorities. Meyer proposed a proximal–distal model. Distal stress processes, such as harassment, the experience of exclusion, and rejection, led to the expectation of negative effects and determined proximal processes, that are internal and can affect an individual’s self-attitude and image (e.g., internalized transphobia, concealment, shame, and the expectation of rejection) (See Figure 1). Despite being introduced almost 20 years ago, this model remains valuable in guiding research in this field by theoretically framing stressors for minorities and highlighting potential areas for intervention at both the individual [13] and community levels [14].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of Minority Stress Theory.

Among distal stressors, traumatic experiences, often resulting from systemic discrimination and societal stigma, are more prevalent among gender-diverse populations, emphasizing the need for targeted research and support [15]. In the general population, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which include direct harm to children (e.g., abuse and neglect) as well as indirect harms (e.g., household dysfunction, such as parental substance use), have been strongly associated with mental disorders, sexual risk-taking behaviors, and alcohol abuse [16]. Even stronger associations have been observed between ACEs and violent behavior, as well as substance abuse [17]. However, evidence specifically addressing childhood trauma in these populations remains limited. For example, ACEs have been associated with substance use, with mental health disorders serving as a moderating factor [18]. A 2021 cohort study by Silveri et al. demonstrated that TGD youth exhibited a higher prevalence of clinical diagnoses at treatment entry and poorer outcomes over a 1-month period compared to CG adolescents [19]. Additionally, this study found higher levels of childhood emotional abuse within the TGD group [19]. Despite the significant impact of ACEs and childhood trauma on gender-diverse populations, there remains a pressing need for comprehensive research to better understand these experiences and inform effective interventions.

Currently, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of comprehensive reviews focusing on childhood trauma and mental health in gender-diverse populations. Existing reviews, such as that by Barr et al., explore specific aspects, such as clinical psychosis, while also emphasizing the critical role of trauma as a stressor and the need for further research [20]. This study seeks to address this gap in the evolving and ‘diverse’ field of mental health research by synthesizing existing evidence on the link between childhood trauma and mental health in TGD individuals, with the goal of stimulating further interest among researchers approaching this topic.

2. Material and Methods

Search Strategy and Quality Assessment

We conducted a systematic search and evaluation of scientific evidence based on “The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement” [21].

On 26th of June 2024 we conducted a search using a meta-search engine provided by EBSCO, accessed through Sapienza University of Rome at https://csb.web.uniroma1.it/it/banche-dati/aggregatore/ebscohost-ricerca-integrata (accessed on 7 February 2025). In our search, we included the following databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL Database, APA PsycInfo, and APA PsychArticles. In the search bar, we typed the following terms: “TI (gender diversity or non-binary gender or gender non-conforming or genderqueer or transgender) AND TI (childhood trauma or childhood abuse or early life trauma or adverse childhood experiences or childhood maltreatment or complex trauma)”. The combination of search terms was designed to encompass a broad spectrum of gender identities and experiences related to trauma, ensuring the inclusion of diverse and underrepresented groups. This systematic review was not registered and prepared based on a pre-established protocol, which represents a limitation. However, we adhered strictly to PRISMA guidelines to ensure methodological rigor [21]. We did not use automation tools in our methodological processes.

We included studies with an observational research design that focused on the relation between childhood trauma and mental health in gender-diverse individuals. We excluded studies focused on unrelated topics, validation studies, doctoral dissertations, letters to the editor, books, commentaries, and studies published in languages other than English. We then conducted a search through the ‘related articles’ function and evaluated two additional studies for inclusion. Two independent authors screened each article, with a third author involved whenever there were discrepancies in the evaluations.

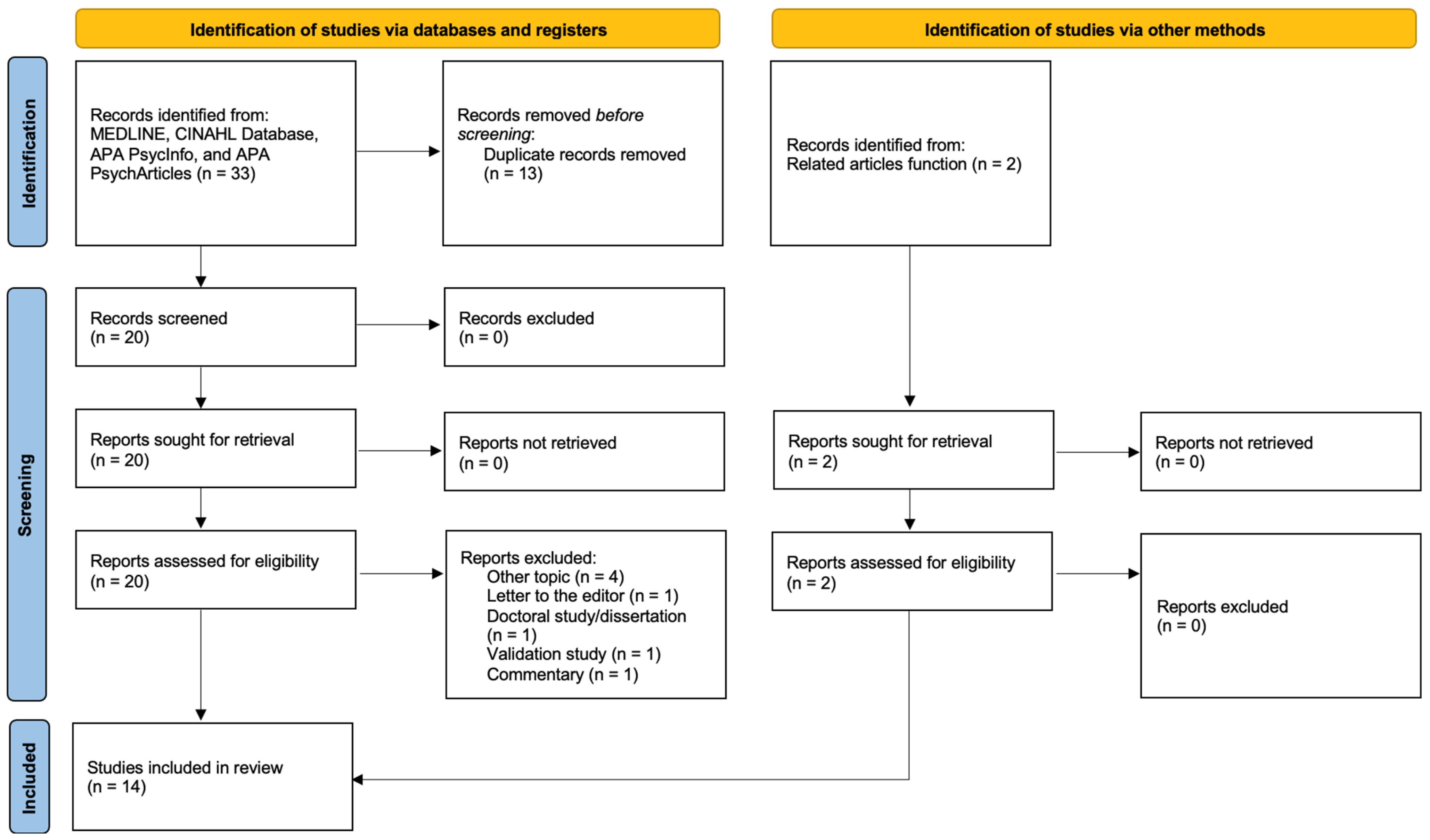

A total of 35 studies were identified, of which 13 were duplicates, 4 focused on unrelated topics, 1 was a letter to the editor, 1 was a doctoral dissertation, 1 was a validation study and 1 was a commentary. Ultimately, 14 high-quality and relevant studies were included in our systematic review to ensure robust and meaningful insights [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram.

To assess the quality of evidence, we used the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS tool) [36]. Supplement Table S1.

3. Results

From a study design perspective, five studies focused exclusively on TG female populations [29,30,31,32,34]. Three studies compared TG individuals with CG individuals [23,24,26], two compared TG women and men [27,35], and two compared TG individuals with non-binary individuals [22,25]. One study involved a cohort of men who have sex with men alongside TG women [33], and only one study included CG, TG, and non-binary individuals [28].

The majority of available evidence pertains to TG individuals. Four studies included comparisons between TG and CG individuals [23,24,26,28], and four studies included non-binary gender identity as a grouping variable [22,24,25,28].

ACEs and various forms of childhood abuse were reported with greater frequency in the TG subgroups of the four included studies that provided comparisons with CG individuals. In this population, traumatic experiences have been associated with mental health outcomes, contributing to elevated stress levels and a higher prevalence of mental disorders, including depression, anxiety, and substance use, with diverse patterns of interaction. These effects appear to be more pronounced among individuals from ethnic minority groups. Moreover, according to our results, gender affirmation (including access to affirming healthcare, legal recognition, and supportive social environments) plays a protective role in TGD individuals who have experienced trauma. Finally, preliminary findings suggest that secure attachment may help protect against depression and substance use in TG women exposed to trauma.

A detailed summary of evidence is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of results.

4. Discussion

All the included studies consistently demonstrate that gender-diverse individuals experience significantly higher rates of ACEs compared to their CG counterparts. Furthermore, the effects of ACEs are often exacerbated by societal stigma, discrimination, and minority stress, particularly for those with intersecting marginalized identities. These findings underscore the need for trauma-informed, culturally sensitive interventions that address both the immediate and cumulative effects of childhood adversity on gender-diverse populations [22,23,24,26,31]. In general, a comprehensive analysis of our results highlights how the impact of ACEs manifests across at least three areas: mental health, physical health, and marginalization due to racial and social factors. These three elements are consistently interconnected, forming a triad that continuously interacts to shape the overall health of gender-diverse individuals.

4.1. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Gender Diversity

First of all, research by Thoma et al. (2021) found that transgender adolescents (TGAs) report significantly higher rates of psychological, physical, and sexual abuse compared to CG adolescents, particularly among trans-gender males and non-binary individuals assigned females at birth [28]. The results were consistent with another included study, conducted by Feil and colleagues (2023), which identified seven clusters of ACEs using the Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology of Exposure (MACE) Scale, revealing that almost one third of TGD individuals reported four or more ACEs, in stark contrast to only 5.7% in the CG group [24]. Finally, De Mattos Russo Rafael et al. (2024) conducted a cross-sectional study in Brazil, and brought to the forefront the prevalence of multiple forms of childhood trauma among TG women, including emotional abuse, physical abuse, and parental rejection [32]. Supporting these results, Schnarrs et al. (2019) documented that TG and gender non-conforming individuals reported significantly higher rates of emotional abuse and physical neglect compared to their CG peers belonging to sexual minorities, with more than half of TG and gender non-conforming participants experiencing four or more ACEs [26]. On the other hand, Biedermann et al. (2021) conducted a multicenter study across four German healthcare centers to evaluate the prevalence of ACEs and their long-term impacts on individuals diagnosed with gender dysphoria [35]. The research revealed that 93% of the participants reported at least mild childhood adversities, with up to one third experiencing severe to extreme forms, including physical abuse, emotional abuse, and bullying by peers. Alarmingly, emotional and sexual abuse were strongly correlated with adult depression and suicidality [28]. These findings align with a large-scale study by Wang et al. (2020) with Chinese adolescents, which reported lower overall and mental health among TG and gender non-conforming individuals compared to CG peers. Notably, gender assigned at birth was the only variable significantly interacting with bullying exposure, underscoring its critical role in this phenomenon. Specifically, males assigned at birth were more frequently subjected to bullying during secondary school [37]. In this regard, the consistent evidence linking traumatic experiences and gender identity underscores the role of aggressive behavior. On the one hand, gender-diverse populations are frequently subjected to aggression or microaggressions [38]. On the other hand, intriguing findings suggest a potential role of gender identity in driving aggressive behavior toward gender non-conforming peers, with negative self-evaluation and low confidence contributing to a greater tendency toward aggression [39]. Tailored interventions should specifically address gender identity and incorporate an interpersonal perspective to better understand and address the critical link between gender diversity and traumatic experiences. Finally, the elevated levels of adversity reflect a broader pattern observed across studies, emphasizing how exposure to ACEs intensifies the risk of poor mental health outcomes in both sexual and gender minorities [40,41,42].

4.2. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Mental Health

In gender-diverse populations, a history of childhood trauma has been associated with an increased risk of various mental disorders, as well as anti-conservative behaviors. Overall, the results of our review highlighted that childhood traumatic experiences in the population under study were associated with depression [24,29,31,34,35], anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder [24]. Notably, a specific focus was placed on the association with an increased risk of suicide attempts [29], which aligns with existing literature linking childhood traumatic experiences to post-traumatic stress disorder [43]. Furthermore, there is evidence supporting the differential impact of individual traumatic experiences on the severity of post-traumatic, dissociative, and mood-related dimensions in adult patients [44]. The specific topic of suicidality was explored by Cao et al. (2023), who found that emotional, physical, and sexual abuse were significant predictors of non-suicidal self-injury among TG individuals [27]. Emotional dysregulation emerged as a key mediator in this relation, suggesting that addressing this aspect could be crucial for reducing NSSI risk. Similarly, Chen et al. (2023) explored the sequelae of CSA among Chinese TG women and its profound effects on mental health [30]. The study revealed that individuals with a history of CSA were significantly more likely to develop maladaptive coping mechanisms, including self-harm and risky behaviors such as unprotected sexual practices. Emotional dysregulation emerged as a pivotal mediator, underlining the necessity of addressing underlying emotional trauma to reduce adverse psychological outcomes. The findings align with prior research demonstrating that childhood trauma disrupts emotional regulation, increasing vulnerability to mental health disorders, including depression and anxiety [27]. Moreover, in light of current evidence, childhood adversities intensify following the disclosure of gender diversity, further increasing the risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality [28,45,46,47]. Given these effects, emotional regulation emerges as a key target for focused and effective psychotherapeutic interventions [26,28,31]. When considering the role of psychotherapies in treating mental health disorders that may arise in these populations, noteworthy evidence has emerged regarding the effectiveness of psychodynamic psychotherapy. Sizemore et al. (2022) investigated the mediating role of depression and the moderating effect of secure attachment in the relation between CSA and substance use. Their findings revealed that TG women with histories of CSA were significantly more likely to exhibit substance use disorders and symptoms of alcohol use problems, largely mediated by increased depressive symptoms [34]. Notably, individuals with secure attachment styles demonstrated lower levels of depression and substance use, even in the presence of CSA. These findings shine a light on the protective role of secure attachment against maladaptive coping behaviors in this population. Current evidence confirms that TG and non-binary individuals experience higher rates and levels [48] of anxiety and depression across different ethnic groups [49], particularly among those assigned female at birth and in relation to minority stress [50]. Within the minority stress framework, the expectation of rejection and internalized transphobia have been reported to play a significant role in this phenomenon [51], indicating potential areas for intervention through targeted psychotherapies. Indeed, higher levels of gender identity pride have been linked to lower levels of depression in TGD adults [52]. In this regard, it is crucial to emphasize that fostering assistance begins with acknowledging traumatic experiences but should prioritize building upon positive ones. Positive experiences should occupy a central role in addressing trauma, as evidence demonstrates their ability to mitigate risks to both general and mental health outcomes [53], even among populations where such experiences might be underrepresented, such as gender-diverse youth [54]. A recent study conducted with Indigenous peoples of the Midwestern United States and Canada showed that the negative association between ACEs and well-being could be counteracted by protective factors, such as benevolent childhood experiences, family satisfaction, and emotional support [55]. This evidence underscores the importance of conceptualizing resilience in psychology not as an intrinsic trait but as a quality that can be nurtured through support [56]. In the field of mental health, evidence consistently underscores the importance of addressing the needs of gender-diverse populations, fostering therapeutic approaches tailored to the unique challenges faced by these groups.

4.3. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Social Stressors

A second critical area influenced by childhood adversities is the intersection of racial and social factors. Leone D.W. (2023) examined ACEs and their impacts on the mental health of TG individuals in Kenya, emphasizing the compounded challenges faced by those in low-resource and highly stigmatizing environments [25]. The study documented widespread exposure to ACEs, with almost all of the respondents reporting at least four types of adversities. Once again, emotional abuse emerged as the most prevalent, followed by physical abuse and neglect. Leone’s work demonstrated a strong positive correlation between ACE scores and psychological distress, including heightened risks of depression, suicidal ideation, and reduced social support. Ricks and Horan (2023) also highlighted the severe impact of childhood trauma among black TG women, revealing that 40.6% of their study participants had experienced CSA, which was strongly associated with elevated rates of depression, anxiety, and body dissatisfaction [26,31]. These results showcase the intersectionality of trauma and structural inequalities, as the lack of resources and pervasive stigma exacerbate the impacts of childhood adversity on TG individuals. Gender-diverse individuals belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups might consequently be exposed to a form of compounded marginalization, with a more profound impact on their well-being. Moreover, the effects of CSA and ongoing discrimination were linked to a higher likelihood of suicide attempts in adulthood [57]. In the literature, it has been shown that gender-diverse individuals belonging to ethnic minorities are inherently exposed to a higher number of adverse childhood events. For instance, a recent study published in 2024 reported that over one third of black sexually minoritized men and black TG women had experienced four or more ACEs, with emotional abuse being the most common [58]. King et al. (2024) investigated how structural racism and cisgenderism exacerbate the effects of ACEs on both mental and physical health among TG people of color, showing how ACEs were associated with poor mental health with an increased effect in the sub-sample including people of color [23]. Minority status, often linked to social exclusion, hinders access to healthcare and socio-economic advancement, increasing the risk of both mental and physical health issues. To this end, TGD populations in different countries may encounter varying social factors that either facilitate or hinder their access to effective healthcare services. For instance, in China, it has been indicated that belonging to a TGD population can limit access to professional mental health services and gender-affirming care. A key factor in this limitation is the fear of discrimination, which discourages the intentional use of mental health services [55]. These findings underscore the importance of addressing both past traumas and ongoing social stressors. Considering all these aspects may enhance the efficacy of interventions targeting individuals facing multiple layers of marginalization. Nevertheless, one of the prospects for expanding the minority stress theory involves the integration of a cross-cultural perspective [14]. Although the majority of the included studies were conducted in Western countries, this review also integrates data from South America, Africa, and Asia. In general, we observed consistent alignment in the results across the various studies included. However, it is crucial to emphasize that the relationship between minority stressors and individuals may be significantly influenced by the value system underlying the culture to which individuals belong. This factor may vary not only across different countries but also over different time periods of observation. The legislative system and social interventions aimed at supporting these populations can influence the level of discrimination and access to protective factors, such as mental health services, providing an additional area to consider when addressing the health outcomes of gender minorities.

4.4. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Physical Health

Finally, another area of focus is physical health. In gender-diverse populations, particularly among TG individuals, much of the evidence centers on sexual health, including both an increased risk of sexually transmitted infections and heightened vulnerability to traumatic relational dynamics. Childhood sexual abuse and other forms of trauma are strongly linked to increased vulnerability to risky behaviors in TG individuals, such as substance use and high-risk sexual activities, often as a result of systemic marginalization and lack of access to supportive resources. Xavier Hall et al. (2021) examined how the timing of childhood sexual abuse impacts health outcomes differently among men who have sex with men (MSM) and TG women. In particular, their study found that CSA experienced during adolescence was strongly associated with higher rates of substance use, suicidal thoughts, and unsafe sexual practices, such as engaging in condomless sex [33]. Adolescence is a period of significant psychological and social development, making individuals more vulnerable to developing maladaptive coping mechanisms when exposed to trauma. Expanding upon this, Fontanari et al. (2016) examined the impact of childhood abuse, particularly emotional and sexual abuse, on transgender women in Brazil. The authors found an increased likelihood of involvement in sex work, an association with HIV infection, and an elevated prevalence of substance use disorders among this population [29]. Thus, childhood maltreatment appears to be associated with socioeconomic marginalization, further exacerbating the vulnerability of these populations. Further emphasizing the connection between early trauma and health outcomes, Strenth et al. (2024) associated ACEs with overall health. Traumatic experiences have been reported to increase the number of days of physical illness, with mental distress, discrimination, and gender non-affirmation acting as mediators of this effect [22]. In relation to this topic, existing evidence outlines lower levels of engagement in sports and physical activity [59] and higher rates of being overweight [60] among transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) individuals, extending findings on the influence of social factors on the health of binary genders [61] to include gender diversity.

Overall, the available literature supports the three areas identified in our systematic review, linking traumatic experiences and mental health with gender diversity. The impact of traumatic experiences is reflected not only on mental health but also on physical health, both directly and indirectly. Adopting a comprehensive approach that considers the impact of traumatic experiences in therapeutic interventions for gender-diverse populations can provide valuable insights for understanding and treatment. This approach has the potential to positively influence both mental and physical health, including the integration of social interventions when necessary.

4.5. Limitations

This systematic review has potential limitations in generalizability due to the evolving and variable terminology within the field of gender studies. The search terms were selected based on widely accepted terminology at the time of the review; however, given the rapidly evolving language in gender studies, this approach may have restricted the inclusion of all the relevant evidence. Furthermore, the relatively low number of eligible articles underscores the ongoing scarcity of research on the health of gender-diverse populations. While the majority of the existing evidence pertains to TG populations, this highlights a significant research gap regarding the health and well-being of non-binary and other gender-diverse individuals, who remain underrepresented in current studies. Finally, the included studies exhibited variability in the mean age of the populations, with only one specifically focusing on adolescents. Due to the limited number of studies, it is not possible to synthesize findings by age group or assess how the impact of traumatic events varies based on the age of occurrence. Future research should investigate the potential evolutionary trajectories of childhood trauma, exploring resilience and vulnerability factors across different life stages and considering the timing of traumatic events.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study underscore the prevalence of childhood traumatic experiences in gender-diverse populations, with emotional abuse standing out among other forms of ACEs. Current evidence in the literature consistently supports the association between childhood trauma, in its various manifestations, and mental health disorders, particularly anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and stress-related disorders, with these effects often exacerbated by intersecting social stressors and systemic inequalities. The effects of traumatic experiences also extend to physical health, significantly influenced by social stressors. While existing evidence often focuses on sexual health outcomes, broader studies are needed to explore the full range of physical health impacts in gender-diverse populations.

Gender minorities are exposed to both proximal stressors (e.g., discrimination, stigma, and socioeconomic conditions) and distal stressors (e.g., childhood trauma), which represent critical dimensions to consider for improving the effectiveness of personalized interventions. Moreover, the results of this review suggest a degree of agreement between studies conducted in countries with fundamentally different cultural backgrounds. This finding encourages the exploration of cultural factors that influence attitudes toward gender minorities, either by increasing stress or by fostering resilience within these communities. This could lead to potential applications for both individual-focused interventions and public health strategies aimed at protecting these minorities. Additionally, current evidence points to future directions in studying the effectiveness of targeted psychotherapeutic interventions for addressing mental health challenges in these populations. Given the unique factors influencing the overall and mental health of TGD individuals, as well as the impact of traumatic experiences, future research should prioritize longitudinal studies to identify tailored treatment and protection strategies for these communities. This includes exploring the protective role of positive childhood and adult experiences at both the individual and community levels.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/psychiatryint6010013/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.C., B.A. and J.F.A. methodology, B.A., J.F.A. and M.N.M.; validation, A.D.C., B.A., J.F.A. and M.N.M.; investigation, B.A., F.S., J.F.A. and S.M.; data curation, B.A., F.S., J.F.A. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A. and J.F.A.; writing—review and editing, all authors; and supervision, S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Parsons, L.C.; Reiss, P.L. Breaking through the Glass Ceiling: Women in Executive Leadership Positions—Part I. SCI Nurs. Publ. Am. Assoc. Spinal Cord Inj. Nurses 2004, 21, 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wegge, J.; Roth, C.; Neubach, B.; Schmidt, K.-H.; Kanfer, R. Age and Gender Diversity as Determinants of Performance and Health in a Public Organization: The Role of Task Complexity and Group Size. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1301–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merryfeather, L. A Personal Epistemology: Towards Gender Diversity. Nurs. Philos. Int. J. Healthc. Prof. 2011, 12, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, N.; Yip, A.K.-T.; Bouman, W.P.; Marshall, E.; Arcelus, J. The Terminology of Identities between, Outside and beyond the Gender Binary—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Transgenderism 2019, 20, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, R.J. A Further Contribution to the Study of Gender Identity. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1968, 49, 364–369. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association APA Dictionary of Psychology 2023. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/gender-identity (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Rubin, J.D.; Atwood, S.; Olson, K.R. Studying Gender Diversity. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polderman, T.J.C.; Kreukels, B.P.C.; Irwig, M.S.; Beach, L.; Chan, Y.-M.; Derks, E.M.; Esteva, I.; Ehrenfeld, J.; Heijer, M.D.; Posthuma, D.; et al. The Biological Contributions to Gender Identity and Gender Diversity: Bringing Data to the Table. Behav. Genet. 2018, 48, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.E.; Herman, J.L.; Rankin, S.; Keisling, M.; Mottet, L.; Anafi, M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey; National Center for Transgender Equality: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Almazan, A.N.; Keuroghlian, A.S. Association Between Gender-Affirming Surgeries and Mental Health Outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelutiu-Weinberger, C.; English, D.; Sandanapitchai, P. The Roles of Gender Affirmation and Discrimination in the Resilience of Transgender Individuals in the US. Behav. Med. 2020, 46, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, J.; Schoebel, V.; Vercruysse, C. Perceptions of Resilience and Coping Among Gender-Diverse Individuals Using Photography. Transgender Health 2019, 4, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, D.M.; Meyer, I.H. Minority Stress Theory: Application, Critique, and Continued Relevance. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 51, 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, D.J.; Mathews, B.; Pacella, R.; Scott, J.G.; Finkelhor, D.; Meinck, F.; Erskine, H.E.; Thomas, H.J.; Lawrence, D.M.; Haslam, D.M.; et al. The Prevalence and Nature of Multi-Type Child Maltreatment in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2023, 218 (Suppl. S6), S19–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, P.; Cook, A.; Winter, S.; Watson, V.; Wright Toussaint, D.; Lin, A. Mental Health Issues and Complex Experiences of Abuse Among Trans and Gender Diverse Young People: Findings from Trans Pathways. LGBT Health 2020, 7, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The Effect of Multiple Adverse Childhood Experiences on Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigsby, T.J.; Claborn, K.R.; Stone, A.L.; Salcido, R.; Bond, M.A.; Schnarrs, P.W. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Substance Use, and Self-Reported Substance Use Problems Among Sexual and Gender Diverse Individuals: Moderation by History of Mental Illness. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2023, 16, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveri, M.M.; Schuttenberg, E.M.; Schmandt, K.; Stein, E.R.; Rieselbach, M.M.; Sternberg, A.; Cohen-Gilbert, J.E.; Katz-Wise, S.L.; Blackford, J.U.; Potter, A.S.; et al. Clinical Outcomes Following Acute Residential Psychiatric Treatment in Transgender and Gender Diverse Adolescents. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2113637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.M.; Roberts, D.; Thakkar, K.N. Psychosis in Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Individuals: A Review of the Literature and a Call for More Research. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 306, 114272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strenth, C.R.; Smith, M.; Gonzalez, L.; Grant, A.; Thakur, B.; Levy Kamugisha, E.I. Mediational Pathways Exploring the Link between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Physical Health in a Transgender Population. Child Abus. Negl. 2024, 149, 106678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.M.; Fleischer, N.L.; Operario, D.; Chatters, L.M.; Gamarel, K.E. Inequities in the Distribution of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Their Association with Health among Transgender People of Color. Child Abus. Negl. 2024, 149, 106654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feil, K.; Riedl, D.; Böttcher, B.; Fuchs, M.; Kapelari, K.; Gräßer, S.; Toth, B.; Lampe, A. Higher Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Transgender Than in Cisgender Individuals: Results from a Single-Center Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, D.W. The Relationship between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Mental Health Issues among Transgender Individuals in Kenya. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2024, 28, 592–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnarrs, P.W.; Stone, A.L.; Salcido, R.; Baldwin, A.; Georgiou, C.; Nemeroff, C.B. Differences in Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Quality of Physical and Mental Health between Transgender and Cisgender Sexual Minorities. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 119, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; He, Z.; Xiang, Z.; Guan, H.; Yan, N.; Qiang, Y.; Li, M. The Relationship between Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Childhood Abuse in Transgender People: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1062601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoma, B.C.; Rezeppa, T.L.; Choukas-Bradley, S.; Salk, R.H.; Marshal, M.P. Disparities in Childhood Abuse Between Transgender and Cisgender Adolescents. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2020016907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontanari, A.M.V.; Rovaris, D.L.; Costa, A.B.; Pasley, A.; Cupertino, R.B.; Soll, B.M.B.; Schwarz, K.; da Silva, D.C.; Borba, A.O.; Mueller, A.; et al. Childhood Maltreatment Linked with a Deterioration of Psychosocial Outcomes in Adult Life for Southern Brazilian Transgender Women. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chang, R.; Hu, F.; Xu, C.; Yu, X.; Liu, S.; Xia, D.; Chen, H.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; et al. Exploring the Long-Term Sequelae of Childhood Sexual Abuse on Risky Sexual Behavior among Chinese Transgender Women. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1057225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricks, J.M.; Horan, J. Associations Between Childhood Sexual Abuse, Intimate Partner Violence Trauma Exposure, Mental Health, and Social Gender Affirmation Among Black Transgender Women. Health Equity 2023, 7, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafael, R.M.R.; Silva, N.L.; Depret, D.G.; Gonçalves de Souza Santos, H.; Silva, K.P.D.; Catarina Barbachan Moares, A.; Braga do Espírito Santo, T.; Caravaca-Morera, J.A.; Wilson, E.C.; Moreira Jalil, E.; et al. Childhood Parental Neglect, Abuse and Rejection Among Transgender Women: A Cross-Sectional Study in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J. Interpers. Violence 2025, 40, 1484–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier Hall, C.D.; Moran, K.; Newcomb, M.E.; Mustanski, B. Age of Occurrence and Severity of Childhood Sexual Abuse: Impacts on Health Outcomes in Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women. J. Sex Res. 2021, 58, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sizemore, K.M.; Talan, A.; Forbes, N.; Gray, S.; Park, H.H.; Rendina, H.J. Attachment Buffers against the Association between Childhood Sexual Abuse, Depression, and Substance Use Problems among Transgender Women: A Moderated-Mediation Model. Psychol. Sex. 2022, 13, 1319–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biedermann, S.V.; Asmuth, J.; Schröder, J.; Briken, P.; Auer, M.K.; Fuss, J. Childhood Adversities Are Common among Trans People and Associated with Adult Depression and Suicidality. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 141, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a Critical Appraisal Tool to Assess the Quality of Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Yang, Y.; Drescher, J.; Li, R.; Yin, W.; Yu, R.; Wang, S.; Deng, W.; Jia, Q.; et al. Mental Health Status of Cisgender and Gender-Diverse Secondary School Students in China. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2022796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSon, J.J.; Andover, M.S. Microaggressions Toward Sexual and Gender Minority Emerging Adults: An Updated Systematic Review of Psychological Correlates and Outcomes and the Role of Intersectionality. LGBT Health 2024, 11, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauletti, R.E.; Cooper, P.J.; Perry, D.G. Influences of Gender Identity on Children’s Maltreatment of Gender-Nonconforming Peers: A Person × Target Analysis of Aggression. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 106, 843–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, A.; Herrick, H.; Proescholdbell, S. Adverse Childhood Experiences Related to Poor Adult Health Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.P.; Blosnich, J. Disparities in Adverse Childhood Experiences among Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Adults: Results from a Multi-State Probability-Based Sample. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H.; Brown, T.N.T.; Herman, J.L.; Reisner, S.L.; Bockting, W.O. Demographic Characteristics and Health Status of Transgender Adults in Select US Regions: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2014. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.L.; Rosario, M.; Corliss, H.L.; Koenen, K.C.; Austin, S.B. Childhood Gender Nonconformity: A Risk Indicator for Childhood Abuse and Posttraumatic Stress in Youth. Pediatrics 2012, 129, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalinski, I.; Teicher, M.H.; Nischk, D.; Hinderer, E.; Müller, O.; Rockstroh, B. Type and Timing of Adverse Childhood Experiences Differentially Affect Severity of PTSD, Dissociative and Depressive Symptoms in Adult Inpatients. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, A.H.; D’Augelli, A.R.; Howell, T.J.; Hubbard, S. Parent’ Reactions to Transgender Youth’ Gender Nonconforming Expression and Identity. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2005, 18, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ystgaard, M.; Hestetun, I.; Loeb, M.; Mehlum, L. Is There a Specific Relationship between Childhood Sexual and Physical Abuse and Repeated Suicidal Behavior? Child Abus. Negl. 2004, 28, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.; Cohen, P.; Johnson, J.G.; Smailes, E.M. Childhood Abuse and Neglect: Specificity of Effects on Adolescent and Young Adult Depression and Suicidality. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1999, 38, 1490–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, F.H.; Carl, A.; Woodcock, L.; Frey, L.; Dake, E.; Matthews, D.D.; Russell, K.J.; Adkins, D. Differences in Patient and Parent Informant Reports of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in a Clinical Sample of Transgender and Gender Diverse Youth. LGBT Health 2021, 8, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.M.; Chiu, C.; Dolotina, B.; Kirakosian, N.; King, D.S.; Grasso, C.; Potter, J.; Mayer, K.H.; O’Cleirigh, C.; Batchelder, A.W. Disparities in Depression and Anxiety at the Intersection of Race and Gender Identity in a Large Community Health Sample. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 365, 117582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.; Butler, C.; Cooper, K. Gender Minority Stress in Trans and Gender Diverse Adolescents and Young People. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1182–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicane, M.J.; Ciesla, J.A. Associations between Minority Stress, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation and Attempts in Transgender and Gender Diverse (TGD) Individuals: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 91, 102113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, B.M.; Chen, D.; Olson-Kennedy, J.; Chan, Y.-M.; Ehrensaft, D.; Garofalo, R.; Rosenthal, S.M.; Tishelman, A.; Hidalgo, M.A. High Internalized Transphobia and Low Gender Identity Pride Are Associated With Depression Symptoms Among Transgender and Gender-Diverse Youth. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2023, 72, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, L.; Elcombe, E.; Blythe, S.; Grace, R.; Donohoe, K.; Sege, R. The Impact of Positive and Adverse Experiences in Adolescence on Health and Wellbeing Outcomes in Early Adulthood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, D.; Purdue, E.L.; Jones, J.A.; Breeze, J.L.; Chen, Y.; Sege, R. Protective Factors Associated with Reduced Substance Use and Depression among Gender Minority Teens. J. LGBT Youth 2024, 21, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, K.A.; Hautala, D.S.; Aulandez, K.M.W.; Walls, M.L. The Resounding Influence of Benevolent Childhood Experiences. Transcult. Psychiatry 2024, 61, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonu, S.; Mann, K.; Potter, J.; Rush, P.; Stillerman, A. Toward Integration of Trauma, Resilience, and Equity Theory and Practice: A Narrative Review and Call for Consilience. Perm. J. 2024, 28, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grummitt, L.; Baldwin, J.R.; Lafoa’i, J.; Keyes, K.M.; Barrett, E.L. Burden of Mental Disorders and Suicide Attributable to Childhood Maltreatment. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharma, C.; Keyes, K.M.; Rudolph, K.E.; Shrader, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-T.; Schneider, J.; Duncan, D.T. Adverse Childhood Experiences among Black Sexually Minoritized Men and Black Transgender Women in Chicago. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, S.M.; Brown, C.; Gower, A.L.; Eisenberg, M.E.; McPherson, L.E.; Rider, G.N. Sport and Physical Activity Among Transgender, Gender Diverse, and Questioning Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2023, 72, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, C.; Marconi, M.; Ruocco, A.; Ristori, J.; Bonadonna, S.; Pivonello, R.; Meriggiola, M.C.; Lombardo, F.; Motta, G.; Crespi, C.M.; et al. Dietary Habits, Physical Activity and Body Mass Index in Transgender and Gender Diverse Adults in Italy: A Voluntary Sampling Observational Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. The Influence of Social Factors on Gender Health. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 1631–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).