Abstract

Violence in psychiatric settings presents a significant risk to patients, staff, and society at large. With over 400 risk assessment tools available globally, their applications and the risks they assess vary, allowing for diverse use in different situations. This scoping review investigated the risk management tools utilized in North America’s forensic psychiatry and acute psychiatric units, aiming to identify which ones are mainly used. A comprehensive search was conducted across PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO databases, following PRISMA Guidelines, covering the literature from their inception date until 2023. Criteria for study inclusion required a focus on risk management tool use in forensic or acute psychiatric settings, originality (original studies, case reports, or systematic reviews), and a North American context. Out of 3059 identified studies, 40 were thoroughly analyzed. Commonly used risk assessment scales include HARM-FV, eHARM-FV, HCR-20, PCL-R, START, BVC, and DASA, with their reliability varying by the clinical context and the assessed population. The review highlights the heterogeneous application of static and dynamic scales across clinical settings, underscoring a need for more precise tools to improve risk assessments in forensic psychiatry, signaling a call for the development and validation of more sophisticated assessment instruments.

1. Introduction

1.1. Violence in Psychiatric Settings

Violence is a reality across various healthcare settings, but managing it is particularly important in forensic psychiatry to facilitate the patient’s rehabilitation [1]. The presence of violence in psychiatric environments poses risks not only to the patients themselves but also to the staff and the wider society [2]. These risks materialize when the potential for agitation or harm is overlooked, potentially prolonging the patient’s reintegration into society, and increasing the likelihood of harm [3,4]. Furthermore, it can affect the productivity of staff members and contribute to burnout [5]. Notably, a recent qualitative study on registered nurses reported that those working in acute care psychiatric units face an elevated risk and often encounter violent and aggressive behavior from patients [6]. Even shift workers are especially at risk of encountering physical violence [7]. While the prevalence of violence in psychiatric wards varies greatly, the literature is consistent in reporting that future studies should prioritize examining the early stages of aggression like agitation, as well as factors conducive to preventing aggression such as ward and staff dynamics, with potential implications for staffing and ward management practices [8,9].

1.2. Risk Factors When Assessing for Violence

Various factors can contribute to predicting violence in patients. These include environmental influences like exposure to violence, poverty, and unstable living conditions; a personal or family history of violence; certain mental health diagnoses, which may or may not be compounded by substance use; and traits such as a lack of empathy or impulsivity [10,11,12,13,14]. Additional patient-related factors to consider are gender, with males and younger individuals being more prone to violence, noncompliance with treatment, and access to weapons, among others [14]. A patient’s background, including a history of fire-setting, cruelty to animals, age at first arrest, and the number of arrests, is also relevant when assessing violence [14].

Both static and dynamic indicators play essential roles in risk assessment tools. Dynamic risk factors, which can change with intervention, must meet three criteria: they must precede and elevate the risk of violence, be capable of change, and have a causal relationship with violence risk, meaning their increase (or decrease) can predict a corresponding change in violence risk [15,16].

1.3. Risk Assessment Tools

Guidelines around the globe recommend structured assessment tools like the Historical Clinical and Risk Management (HCR-20), Psychopathy Checklist Revised Screening Version (PCL-SV), and the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) for evaluating risk [17]. Currently, there are over 400 risk assessment tools available internationally [18]. Depending on the specific situation and risk being assessed, various risk management instruments can be utilized. For instance, certain scales are designed for assessing acute risk within a 24 h period, such as the Dynamic Appraisal of Situation Aggression-Inpatient Version (DASA-IV), while others, like the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START), are geared towards short-term evaluation [19,20]. These tools are invaluable for forensic psychiatrists and clinicians, enabling them to make well-informed decisions about the management and treatment of individuals in their care. They offer the capability to predict the risk of violence over short or long periods, thereby guiding appropriate preventive measures. Although there is existing literature on various tools, there is a gap in providing an overview of the tools specifically utilized within the North American context. Such an exploration of the literature is important for effectively utilizing the reported tools and for further developing tools tailored to the psychiatric challenges encountered by patients and staff in North America. The recent literature stresses the need for better data regarding risk assessment tools in the context of forensic psychiatry [21].

1.4. Objectives of the Study

This scoping review aims to examine all the risk management tools currently in use within forensic psychiatry and acute psychiatric contexts across North America. The objective is to report metrics on their effectiveness in the North American contexts to evaluate their use in these clinical settings, given their significance for the wellbeing of patients, medical personnel, and society. It is hypothesized that a wide variety of clinical appraisal tools will be identified across these contexts, and they will vary in terms of their effectiveness.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

A systematic search was carried out in the electronic databases of Pubmed, Embase, and PsycINFO from 2010 until 2023 to assess the contemporary literature. The search was performed by using inclusive keywords for the fields of psychometric tools (i.e., psychometrics), risk evaluation (i.e., violence, aggression), and risk evaluation in forensic or acute psychiatric contexts (i.e., psychiatric department, hospital, psychiatric). Other studies were found by using additional records that were identified through cross-referencing. Furthermore, Appendix A contains the complete electronic search strategy and the Supplementary Material S1 contains the PRISMA for scoping review checklist. This search method was developed by the main author of this article and a mental health-specialized librarian working at the Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal. The search was accomplished by MAR, OLCH, and AH in 2023. Searches were restricted to English or French language sources, and, at first, there were no limitations about the setting, the date, or the geographical location of the studies found.

2.2. Study Eligibility

For studies to be considered for inclusion in the analysis, they were required to meet the following criteria: (1) the focus of the article should be on the utilization of a risk management tool, (2) it must involve patients within forensic psychiatry or acute psychiatry settings, (3) the publication needs to be an original study, case report, or systematic literature review, (4) the research should have been conducted in North America, and (5) the article must be written in either English or French. Additionally, (6) the publication date of all articles must be from 2010 onwards to encompass the most recent literature on the subject.

2.3. Data Extraction

MAR and OLCH extracted data using a Microsoft Excel (version 16.0) form, which was then cross-validated by AH and SBP. The information gathered included the type of risk assessment tool used, the number of items for each tool, participant numbers, study location, key indicators of interest from each study, and the overall conclusions. These data were compiled and included in the document.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Selected Studies

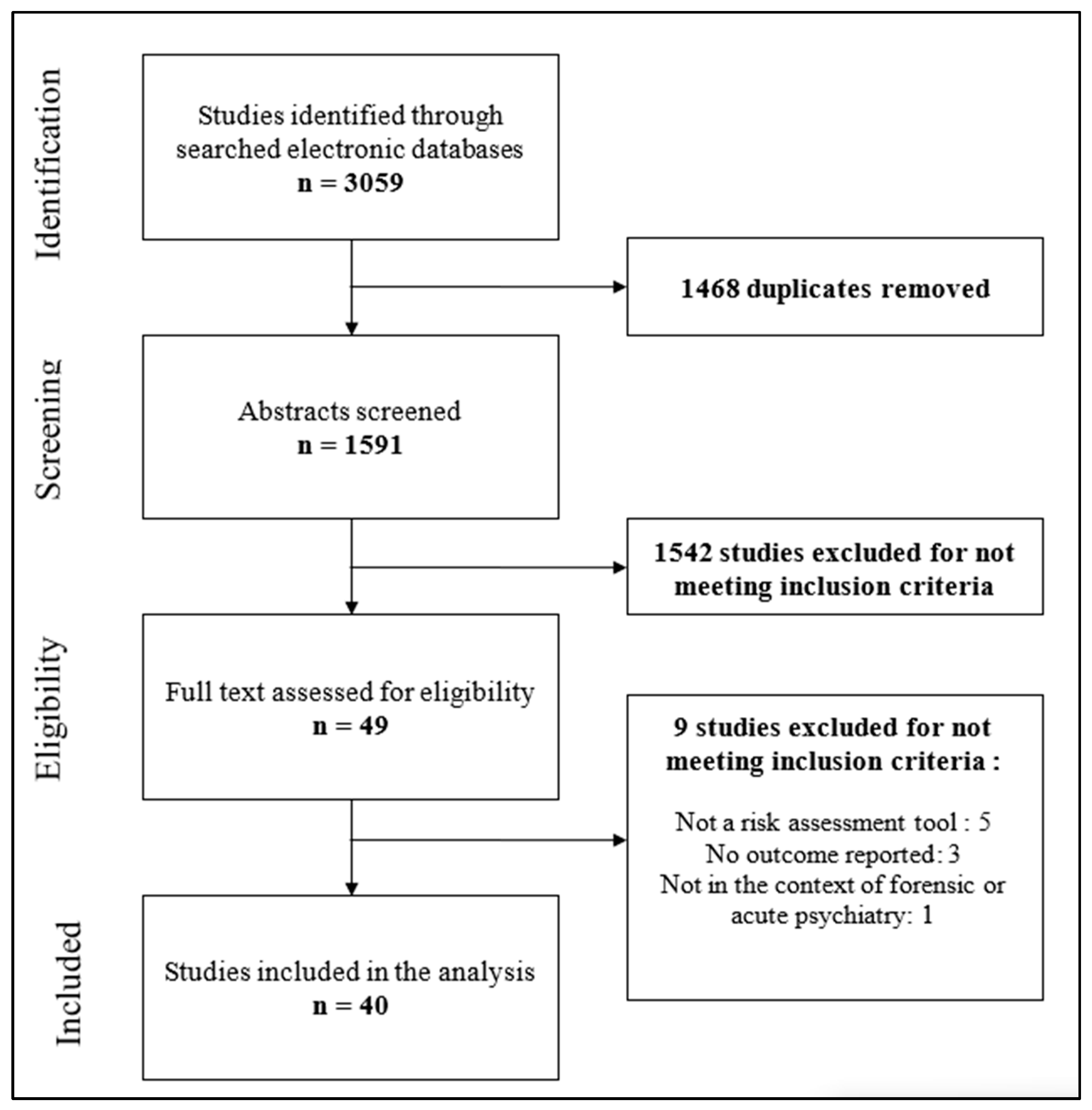

Our systematic review focused on articles that evaluated violence risk scales within forensic psychiatry or acute psychiatric settings in North America. Initially, we found 3059 articles related to the topic. After removing duplicates, we were left with 1591 articles. Further screening based on titles and abstracts, according to our inclusion criteria, narrowed the selection down to 49 articles for in-depth review. We excluded articles which did not include risk assessment tools (N = 5), those not examining violence risk evaluation tools in forensic or acute psychiatric care settings (N = 1), and those that did not report the outcomes of these tools (N = 3). Ultimately, 40 articles met our inclusion criteria. We opted to exclude studies that solely focused on personality scales, as they did not assess violence risk directly. The PRISMA flowchart detailing the study inclusion process is available in Figure 1. Information on the identified studies and their specifics is outlined in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flowchart for the inclusion of studies.

Table 1.

Detailed results of scoping review study selection.

3.2. Violence Risk Evaluation Tools

3.2.1. Hamilton Anatomy of Risk Management Forensic Version (HARM-FV) and Electronic Hamilton Anatomy of Risk Management Forensic Version (eHARM-FV)

The HARM-FV is a structured clinical judgment tool that encompasses 6 historical and 10 dynamic risk factors [33]. This tool assists clinicians in assessing the risk of aggression and in formulating strategies for managing this risk in the ensuing days and weeks [33]. Within this framework, the Aggressive Incidents Scale (AIS) is integrated; it is a nine-point scale that quantifies aggression levels [46]. The eHARM-FV enables the monitoring of a patient’s progress and the comparison of groups through visual representations generated from data inputted into an electronic version of the HARM-FV. A study compared the HARM-FV with the Brockville Risk Checklist in two samples: one with 36 patients and another with 55 patients in a forensic psychiatry unit in Ontario that assessed the HARM’s predictive validity using the area under the curve (AUC), which ranged from 0.56 to 0.96 based on whether the context was immediate vs. short-term and whether support was available [46]. For the eHARM-FV, the same research found that its predictive validity fluctuated between 0.56 and 0.90 and was again influenced by the duration of the assessment period and the availability of support [46].

3.2.2. Historical Clinical Risk Management 20 (HCR-20)

The HCR-20 emerged as the most frequently examined risk assessment tool across 19 studies. This tool is a structured clinical judgment instrument consisting of 20 items, incorporating both dynamic factors (5 clinical symptoms and 5 risk management items) and static factors (10 historical factors). Its predictive utility for violence was demonstrated as significant (χ2 = 98.28, p < 0.001; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.69) in a study, which analyzed 140 patients in a forensic psychiatry unit in New York who were found not criminally responsible due to mental disorders [29]. Another study in a forensic psychiatry unit with 30 patients in British Columbia showed high interrater reliability for both the total score (0.88) and the final judgment (0.84) [58]. Hogan and colleagues assessed 99 patients in a forensic psychiatric unit in Western Canada, and reported a predictive accuracy of 0.76 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.66 to 0.86, and detailed the reliability of different HCR-20 categories: historical scale (0.93), clinical scale (0.88), and risk scale (0.64) [49]. Also, a comparative study of 68 women to 292 men in a forensic psychiatric unit in Ontario, using the HCR-20, found internal consistencies for historical, clinical, and risk items to be 0.83, 0.77, and 0.58, respectively, as opposed to 0.70, 0.76, and 0.42 in men [42].

3.2.3. Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R)

The PCL-R is a 20-item tool designed to assess the personality traits associated with psychopathy [49]. It was the second most frequently discussed risk assessment instrument, cited in 14 studies. The tool has been adapted into a Youth Version and a Screening Version to accommodate different populations. In the previously mentioned study by Hogan and Olver, the PCL-R demonstrated a predictive accuracy with a 95% CI of 0.63 (0.49, 0.77). A meta-analysis by Ramesh T. et al. (2018) reported the sensitivity of the PCL-R to be 0.53 (95% CI 0.45, 0.63), specificity to be 0.60 (95% CI 0.38, 0.81), PPV to be 0.72 (95% CI 0.63, 0.82), and NPV to be 0.55 (95% CI 0.43, 0.70) [49].

3.2.4. Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START)

The START is a structured clinical judgment tool consisting of 22 dynamic items and is evaluated across two dimensions: strengths and vulnerabilities. A meta-analysis reported the START’s sensitivity at 0.81 (95% CI 0.78–0.89), specificity at 0.60 (95% CI 0.55–0.68), PPV at 0.52 (95% CI 0.44–0.62), and NPV at 0.86 (95% CI 0.82–0.92). Another study involving patients in a forensic psychiatry unit in Western Canada assessed the predictive accuracy of these two factors, finding a score of 0.76 (95% CI 0.65, 0.87) for the vulnerabilities total and 0.69 (95% CI 0.57, 0.81) for the strength total [49]. In evaluating the concordance between the START and HCR-20 among a sample of 120 male patients in a Western Canadian forensic psychiatry unit, the agreement on violence prediction was κ = 0.77 with p < 0.001 [37]. The interrater reliability for the strength factor, the vulnerability factor, and the estimated violence risk were 0.93, 0.95, and 0.85, respectively, using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC2) [37].

3.2.5. Brøset Violence Checklist (BVC)

The BVC is a brief tool for predicting short-term violence, comprising six items, i.e., confusion, irritability, boisterousness, verbal threats, physical threats, and attacks on objects, which are scored as either present or absent. Its effectiveness has been assessed in six of the forty identified articles. A meta-analysis highlighted the BVC’s sensitivity at 0.66 (95% CI 0.41–0.80), specificity at 1.00 (95% CI 0.76–1.00), PPV at 0.37 (95% CI 0.25–0.68), and NPV at 0.99 (95% CI 0.78–0.99) and a diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) of 43.1 (95% CI 29.6–56.6) [61]. In a study involving 222 patients in an acute psychiatric unit in the United States, Sarver et al. (2019) reported the tool’s effect size (dF I) at −1.2260, with a standard error of 0.2033 and a significant Wald chi-square statistic of 36.3521. Meanwhile, Woods and colleagues reported, in their research with 46 patients in a forensic psychiatry unit in Saskatchewan, the BVC to have a Wald score of 29.57 (p < 0.001, Exp(B) = 2.68, 95% CI = 1.88 to 3.82) and an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.73, indicating its utility in assessing the risk of violence [60].

3.2.6. Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression (DASA)

The DASA is an actuarial tool designed to evaluate the risk of imminent aggression within the next 24 h among mental health patients. It includes seven factors: irritability, impulsivity, unwillingness to follow directions, sensitivity to perceived provocation, being easily angered when requests are denied, negative attitudes, and verbal threats. This instrument was mentioned in three articles, including its French version (DASAfr), its Youth Version (DASA-YV), and the standard version. Dumais and colleagues discussed the French version in their study of 77 patients in intensive psychiatric units in Quebec [39]. Their findings indicate the instrument’s moderate predictive ability for aggression towards objects (a next shift AUC of 0.66 (0.58–0.73) vs. a next 24 h AUC 0.66 (0.61–0.71)), and acceptable accuracy for aggression towards others (next shift 0.73 (0.57–0.89) vs. next 24 h 0.71 (0.61–0.81)) and nursing staff (next shift 0.72 (0.59–0.85) vs. next 24 h 0.70 (0.61–0.78)). They concluded that the French version’s predictive accuracy was comparable to the original tool. The DASA-YV adds four items: anxiety or fearfulness, low empathy/remorse, significant peer rejection, and external stressors. Dutch and Patil observed that the DASA-YV’s predictive validity varied from 0.84 (physical aggression towards others) to 0.92 (verbal aggression towards others) in a study of 127 patients in a pediatric and adolescent acute psychiatric unit in the United States [40]. Lastly, a meta-analysis showed that the standard DASA had a sensitivity of 0.73 (0.43–0.75), a specificity of 0.75 (0.69–0.76), a PPV of 0.35 (0.20–0.63), an NPV of 0.99 (0.97–1.00), and a DOR of 10.9 (9.8–12.1) [61].

3.2.7. Other Instruments

The Structured Assessment of Protective Factors for Violence Risk (SAPROF) was examined by Oziel and colleagues and found to have internal scale reliability, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha of 0.72 [53]. This study involved 50 patients in a forensic psychiatry unit in Ontario. In another study, the Imminent Risk Rating Scale (IRRS) was evaluated by Winters and colleagues on 109 patients in a forensic psychiatry unit in the United States [59]. It demonstrated the capability to predict risk for up to two weeks, with sensitivity ranging from 60 to 75% for verbal aggression and 63.4 to 75% for physical aggression and specificity from 83.3 to 88.8% for verbal aggression and 77.1 to 84.7% for physical aggression. This tool was assessed with 301 patients across four locked psychiatric units in the United States. Lastly, the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide Revised (VRAG-R) reported an accuracy of 0.60 (95% CI = 0.44, 0.76) and an AUC of 0.720 [49,51].

3.3. Outcomes

Numerous studies have investigated the effectiveness of various risk assessment tools. Wilson and colleagues reported that the dynamic factors of items C and R in the HCR–20, as well as the START, demonstrated a solid predictive value for future institutional risk, with no significant differences in predictive value between the START and HCR-20 identified [58]. Also, Penney and colleagues concluded in their research that the HCR-20 was more effective in predicting violence than the PCL-R [54]. For forensic patients, certain tools, including the HCR-20, PCL-R, START, VRAG-R, and VRS, proved to be efficient in assessing the risk of violence recidivism [49].

4. Discussion

This scoping review examined the utilization of risk management tools in forensic psychiatry and acute psychiatric units in North America, with the goal of determining the predominant tools used and the metrics associated with their usage. The commonly employed risk assessment scales were the HARM-FV, eHARM-FV, HCR-20, PCL-R, START, BVC, and DASA. Validity and reliability metrics as well as the ability to predict violent events varied greatly across the different tools depending on their context of use and the specific population evaluated.

The identified risk assessment tools in forensic and acute psychiatric settings for the North American context corresponds to what has been previously identified in a systematic literature review on the subject for a broader context [62]. These tools are important as violence remains a major concern in psychiatric units, and while there is a wide variety of scales available for clinicians and staff, major challenges can impact their validity. When developing risk assessment tools, recent research stressed the importance of making them psychometrically sound, concise, consensus-rated, time-efficient, and practical for planning risk management, as well as incorporating user feedback to sustain implementation [63]. This contrasts well with forensic psychology as understanding and forecasting human behavior using psychological categories including personality traits, thought patterns, and past behavior is a common focus of forensic psychology. Forensic psychology also relies heavily on instruments such as the PCL-R, especially when evaluating long-term risk factors [62].

As it was identified in our literature review, many of the studies on risk assessment tools reported favorable accuracies in predicting the risk of violence, and these findings are correlated with the literature that is specifically designed for evaluating the effectiveness of targeted risk assessment tools. As an example, a meta-analysis evaluated the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of the HCR-20 as 0.78 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.00), 0.71 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.00), 0.31 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.56), and 0.94 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.00), respectively [61]. However, these examples contrast the evidence pooled when assessing the reliability and predictive power of these tools. As an example, despite encouraging findings for the accuracy in predicting the risk of violence of risk assessment tools, the recent literature supports that violence risk assessment tools in forensic mental health have mixed evidence of predictive performance, and further research should be conducted in this area [64]. These contrasting results hint towards the fact that more studies are necessary to implement more robust risk assessments tools. It is important to emphasize that tools designed for predicting the risk of violence in penitentiary settings, which focus on measuring societal risk, may not necessarily be suitable for use in closed environments such as hospitals. The ecological validity of these tools must be critically evaluated and contrasted to ensure their applicability across different contexts.

Limitations

This scoping review specifically targets the various risk assessment tools employed in forensic and acute psychiatry settings in North America. The search strategies employed are tailored to this specific context; however, it is worth noting that certain clinical facilities may utilize different tools, which would not be captured in the search if they were not published. Additionally, due to the diversity of population samples across the studies identified, it was not feasible to make direct comparisons of tool performances to form a generalized assessment of their effectiveness.

5. Conclusions

As observed globally, violent incidents occur in North American forensic and acute psychiatric units. Given the higher occurrences of violence in psychiatric settings, utilizing risk assessment tools is crucial to mitigate harm for both staff and patients in these units. This scoping review aims to identify the risk assessment tools utilized for violence in North American psychiatric units. The search strategy led to the identification of several tools, with HARM-FV, eHARM-FV, HCR-20, PCL-R, START, BVC, and DASA being the most cited. Various performance metrics were reported for these tools, indicating variability in their accuracy for predicting violence risk within their specific contexts of use. With so many tools available, it makes us wonder about the limitations of the systematic use of risk assessment tools in psychiatric units. Furthermore, this study lays the groundwork for future research into developing tools for predicting violence risk in North American contexts, where violence remains prevalent and challenging to anticipate.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/psychiatryint6010008/s1, PRISMA-Scoping review Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and S.B.P.; methodology, A.H. and S.B.P.; validation, A.H., M.A.R., O.L.C.-H. and J.-M.A.; formal analysis, A.H., M.A.R. and O.L.C.-H.; investigation, A.H.; resources, A.H.; data curation, A.H. and S.B.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H., M.A.R., O.L.C.-H., J.-M.A. and S.B.P.; writing—review and editing, A.H., M.A.R., O.L.C.-H., J.-M.A., and S.B.P.; visualization, A.H.; supervision, A.H. and S.B.P.; project administration, A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Psychometric tools for screening for violence in psychiatric settings.

Table A1.

Psychometric tools for screening for violence in psychiatric settings.

| Psychometric Tools | Assessment of the Risk of Violence | Psychiatric Settings (Hospitalization) |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptors (MeSH) “Psychometrics”[Mesh] Keywords (title/abstract) Instrument(s) Tool(s) Test(s) Measure(s) Measurement Scale(s) Psychometric(s) | Descriptors (MeSH) “Violence”[Mesh:NoExp] “Aggression”[Mesh:NoExp] AND “Risk Assessment”[Mesh:NoExp] Keywords (title/abstract) Violence Violent Aggression Aggressive AND Assessment(s) Assess Assessing Prediction Predict Predicting Screening AND Risk(s) | Descriptors (MeSH) “Psychiatric Department, Hospital”[Mesh] “Hospitals, Psychiatric”[Mesh] “Inpatients”[Mesh] AND “Mental Disorders”[Mesh] “Mentally Ill Persons”[Mesh] Keywords (title/abstract) Hospital(s) Hospitalised Hospitalized Unit(s) Ward(s) Facility(ies) Setting(s) Inpatient(s) Patient(s) AND Mental Psychiatric |

Appendix A.1. Concept 1

“Psychometrics”[Mesh] OR Instrument[TIAB] OR instruments[TIAB] OR Tool[TIAB] OR tools[TIAB] OR Test[TIAB] OR tests[TIAB] OR Measure[TIAB] OR measures[TIAB] OR Measurement[TIAB] OR Scale[TIAB] OR scales[TIAB] OR Psychometric[TIAB] OR psychometrics[TIAB]

Appendix A.2. Concept 2

((“Violence”[Mesh:NoExp] OR “Aggression”[Mesh:NoExp]) AND “Risk Assessment”[Mesh:NoExp]) OR ((Violence[TIAB] OR violent[TIAB] OR aggression[TIAB] OR aggressive[TIAB]) AND (Assessment[TIAB] OR assessments[TIAB] OR Assess[TIAB] OR assessing[TIAB] OR prediction[TIAB] OR predict[TIAB] OR predicting[TIAB] OR screening[TIAB]) AND (risk[TIAB] OR risks[TIAB]))

Appendix A.3. Concept 3

“Psychiatric Department, Hospital”[Mesh] OR “Hospitals, Psychiatric”[Mesh] OR (“Inpatients”[Mesh] AND (“Mental Disorders”[Mesh] OR “Mentally Ill Persons”[Mesh])) OR ((Hospital[TIAB] OR hospitals[TIAB] OR Hospitalised[TIAB] OR Hospitalized[TIAB] OR Unit[TIAB] OR units[TIAB] OR Ward[TIAB] OR wards[TIAB] OR Facility[TIAB] OR facilities[TIAB] OR setting[TIAB] OR settings[TIAB] OR Inpatient[TIAB] OR inpatients[TIAB] OR patient[TIAB] OR patients[TIAB]) AND (mental[TIAB] OR psychiatric[TIAB]))

Limits: English, French

References

- d’Ettorre, G.; Pellicani, V. Workplace Violence Toward Mental Healthcare Workers Employed in Psychiatric Wards. Saf. Health Work 2017, 8, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkin, G.; Quigg, S.; Paap, H.; Cooney, E.; Peterson, D.; Every-Palmer, S. Places of safety? Fear and violence in acute mental health facilities: A large qualitative study of staff and service user perspectives. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.E.; Shumway, M.; Leary, M.; Mangurian, C.V. Patient Factors Associated with Extended Length of Stay in the Psychiatric Inpatient Units of a Large Urban County Hospital. Community Ment. Health J. 2016, 52, 658–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Chan, H.Y. Factors associated with prolonged length of stay in the psychiatric emergency service. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguglia, A.; Belvederi Murri, M.; Conigliaro, C.; Cipriani, N.; Vaggi, M.; Di Salvo, G.; Maina, G.; Cavone, V.; Aguglia, E.; Serafini, G.; et al. Workplace Violence and Burnout Among Mental Health Workers. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiebert, B.J.; Care, W.D.; Udod, S.A.; Waddell, C.M. Psychiatric Nurses’ Lived Experiences of Workplace Violence in Acute Care Psychiatric Units in Western Canada. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 43, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridenour, M.; Lanza, M.; Hendricks, S.; Hartley, D.; Rierdan, J.; Zeiss, R.; Amandus, H. Incidence and risk factors of workplace violence on psychiatric staff. Work 2015, 51, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, C.; Azizian, A.; Kornbluh, R.; Warburton, K. Prevalence of physical violence in a forensic psychiatric hospital system during 2011–2013: Patient assaults, staff assaults, and repeatedly violent patients. CNS Spectr. 2015, 20, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltens, I.; Bak, M.; Verhagen, S.; Vandenberk, E.; Domen, P.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Drukker, M. Aggression on the psychiatric ward: Prevalence and risk factors. A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, R.D. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised, 2nd ed.; Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, J.W.; Swartz, M.S.; Van Dorn, R.A.; Elbogen, E.B.; Wagner, H.R.; Rosenheck, R.A.; Stroup, T.S.; McEvoy, J.P.; Lieberman, J.A. A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbogen, E.B.; Johnson, S.C. The intricate link between violence and mental disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, A.; Binder, R.; Norko, M.; Swartz, M. Psychiatric violence risk assessment. Am. J. Psychiatry 2012, 169, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chagigiorgis, H.; Michel, S.F.; Seto, M.C.; Laprade, K.; Ahmed, A.G. Assessing short-term, dynamic changes in risk: The predictive validity of the Brockville Risk Checklist. Int. J. Forensic Ment. Health 2013, 12, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coid, J.W.; Ullrich, S.; Kallis, C.; Freestone, M.; Gonzalez, R.; Bui, L.; Igoumenou, A.; Constantinou, A.; Fenton, N.; Marsh, W.; et al. Improving risk management for violence in mental health services: A multimethods approach. In Development of a Dynamic Risk Assessment for Violence; NIHR Journals Library, Ed.; Programme Grants for Applied Research (No. 4.16); NIHR Journals Library: Southampton, UK, 2016; Chapter 18. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396458/ (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Antisocial Personality Disorder: Treatment, Management and Prevention; British Psychological Society: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.P.; Desmarais, S.L.; Hurducas, C.; Arbach-Lucioni, K.; Condemarin, C.; Dean, K.; Doyle, M.; Folino, J.O.; Godoy-Cervera, V.; Grann, M.; et al. International Perspectives on the practical application of Violence Risk Assessment: A Global Survey of 44 countries. Int. J. Forensic Ment. Health 2014, 13, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.D.; Nicholls, T.L.; Martin, M.L.; Desmarais, S.L.; Brink, J. Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START): The case for a new structured professional judgment scheme. Behav. Sci. Law 2006, 24, 747–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, M.L.; Maguire, T.; Ogloff, J.R.P.; Gabriel, J.; Daffern, M. Using the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression (DASA) to assess the impact of unit atmosphere on violence risk assessment. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 30, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, T.; Pugh, J.; Singh, I.; Savulescu, J.; Fazel, S. Risk assessment tools in criminal justice and forensic psychiatry: The need for better data. Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2017, 42, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, S.L.S.; Nussbaum, D. Decision making and aggression in forensic psychiatric inpatients. Crim. Justice Behav. 2010, 37, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasioli, E.; Bieling, P.J.; Hassini, E. An Examination of the Performance of the interRAI Risk of Harm to Others Clinical Assessment Protocol (RHO CAP) in Inpatient Mental Health Settings. Psychiatr. Q. 2021, 92, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasioli, E.; Hassini, E.; Bieling, P.J. A Predictive Model for Estimating Risk of Harm and Aggression in Inpatient Mental Health Clinics. Psychiatr. Q. 2021, 92, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccaccini, M.T.; Chevalier, C.S.; Murrie, D.C.; Varela, J.G. Psychopathy Checklist-Revised Use and Reporting Practices in Sexually Violent Predator Evaluations. Sex. Abus. J. Res. Treat. 2017, 29, 592–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brassard, M.L.; Joyal, C.C. Predicting forensic inpatient violence with odor identification and neuropsychological measures of impulsivity: A preliminary study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 147, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brathovde, A. Improving the Standard of Care in the Management of Agitation in the Acute Psychiatric Setting. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2021, 27, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burk, B.G.; Penherski, P.; Snider, K.; Lewellyn, L.; Mattox, L.; Polancich, S.; Fargason, R.; Waggoner, B.; Caine, E.; Hand, W.; et al. Use of a Novel Standardized Administration Protocol Reduces Agitation Pro Re Nata (PRN) Medication Requirements: The Birmingham Agitation Management (BAM) Initiative. Ann. Pharmacother. 2023, 57, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeldue, M.; Green, D.; Griswold, H.; Schneider, M.; Smith, J.; Belfi, B.; Kunz, M. Using the HCR-20V3 to Differentiate Insanity Acquittees Based on Opinions of Readiness for Transfer. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2018, 46, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charette, Y.; Goossens, I.; Seto, M.C.; Nicholls, T.L.; Crocker, A.G. Is knowledge contagious? Diffusion of violence-risk-reporting practices across clinicians’ professional networks. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 9, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.E.; Brown, A.M.; Griffith, P. The Brøset Violence Checklist: Clinical utility in a secure psychiatric intensive care setting. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 17, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comai, S.; Fuamba, Y.; Rivolta, M.C.; Gobbi, G. Lifetime Cannabis Use Disorder Is Not Associated with Lifetime Impulsive Behavior and Severe Violence in Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders from a High-Security Hospital. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 41, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.N.; Moulden, H.M.; Mamak, M.; Lalani, S.; Messina, K.; Chaimowitz, G. Validating the Hamilton Anatomy of Risk Management-Forensic Version and the Aggressive Incidents Scale. Assessment 2018, 25, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, G.; Crocker, A.G.; Nicholls, T.L.; Seto, M.C. Risk assessment instruments in clinical practice. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2012, 57, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, D.; Mitchell, S.M.; Morgan, R.D.; Scanlon, F. Examining violence among Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity state hospital inpatients across multiple time points: The roles of criminogenic risk factors and psychiatric symptoms. CNS Spectr. 2020, 25, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmarais, S.L.; Nicholls, T.L.; Read, J.D.; Brink, J. Confidence and accuracy in assessments of short-term risks presented by forensic psychiatric patients. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2010, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, S.L.; Nicholls, T.L.; Wilson, C.M.; Brink, J. Using dynamic risk and protective factors to predict inpatient aggression: Reliability and validity of START assessments. Psychol. Assess. 2012, 24, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmarais, S.L.; Van Dorn, R.A.; Telford, R.P.; Petrila, J.; Coffey, T. Characteristics of START assessments completed in mental health jail diversion programs. Behav. Sci. Law 2012, 30, 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumais, A.; Larue, C.; Michaud, C.; Goulet, M.H. Predictive validity and psychiatric nursing staff’s perception of the clinical usefulness of the French version of the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutch, S.G.; Patil, N. Validating a Measurement Tool to Predict Aggressive Behavior in Hospitalized Youth. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2019, 25, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edens, J.F.; McDermott, B.E. Examining the construct validity of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised: Preferential correlates of fearless dominance and self-centered impulsivity. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimbos, T.; Penney, S.R.; Fernane, S.; Prosser, A.; Ray, I.; Simpson, A.I. Gender comparisons in a forensic sample: Patient Profiles and HCR-20:V2 reliability and item utility. Int. J. Forensic Ment. Health 2016, 15, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, L.M.; Green, D.; Griswold, H.; Cabeldue, M.; Belfi, B. Assessing Inpatient Victimization Risk Among Insanity Acquittees Using the HCR-20V3. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2019, 47, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, L.S.; Packer, I.K.; Warnken, W. Assessing risk of violence using structured professional judgment guidelines. J. Forensic Psychol. Pract. 2012, 12, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, K.M.; Contreras, I.M.; Kosiak, K.; Novaco, R.W. Anger rumination and imagined violence as related to violent behavior before and after psychiatric hospitalization. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 1878–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healey, L.V.; Mullally, K.; Mamak, M.; Chaimowitz, G.A.; Ahmed, A.G.; Seto, M.C. Short-term clinical risk assessment and management: Comparing the Brockville Risk Checklist and Hamilton Anatomy of Risk Management. Behav. Sci. Law 2020, 38, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, N.Z.; Simpson, A.I.; Ham, E. The increasing influence of risk assessment on forensic patient review board decisions. Psychol. Serv. 2016, 13, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, N.R.; Olver, M.E. Assessing risk for aggression in forensic psychiatric inpatients: An examination of five measures. Law Hum. Behav. 2016, 40, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, N.R.; Olver, M.E. Static and dynamic assessment of violence risk among discharged forensic patients. Crim. Justice Behav. 2019, 46, 923–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Ledi, D.; Daniels, M.K. Evaluating the concurrent validity of the HCR-20 scales. J. Risk Res. 2013, 16, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, B.E.; Dualan, I.V.; Scott, C.L. The predictive ability of the Classification of Violence Risk (COVR) in a forensic psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, T.L.; Petersen, K.L.; Brink, J.; Webster, C. A clinical and risk profile of forensic psychiatric patients: Treatment team starts in a Canadian service. Int. J. Forensic Ment. Health 2011, 10, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oziel, S.; Marshall, L.A.; Day, D.M. Validating the SAPROF with forensic mental health patients. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2020, 31, 667–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, S.R.; Marshall, L.A.; Simpson, A.I. The assessment of dynamic risk among forensic psychiatric patients transitioning to the community. Law Hum. Behav. 2016, 40, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penney, S.R.; McMaster, R.; Wilkie, T. Multirater reliability of the historical, clinical, and risk management-20. Assessment 2014, 21, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarver, W.L.; Radziewicz, R.; Coyne, G.; Colon, K.; Mantz, L. Implementation of the Brøset Violence Checklist on an Acute Psychiatric Unit. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2019, 25, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starzomski, A.; Wilson, K. Development of a measure to predict short-term violence in psychiatric populations: The Imminent Risk Rating Scale. Psychol. Serv. 2015, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.M.; Desmarais, S.L.; Nicholls, T.L.; Brink, J. The role of client strengths in assessments of violence risk using the short-term assessment of risk and treatability (START). Int. J. Forensic Ment. Health 2010, 9, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, G.M.; Chou, C.; Grydehøj, R.F.; Tully, E. Predictive Utility of the Imminent Risk Rating Scale: Evidence from a Clinical Pilot Study. J. Forensic Nurs. 2023, 19, E1–E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, P.; Olver, M.; Muller, M. Implementing violence and incident reporting measures on a Forensic Mental Health Unit. Psychol. Crime Law 2015, 21, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T.; Igoumenou, A.; Vazquez Montes, M.; Fazel, S. Use of risk assessment instruments to predict violence in forensic psychiatric hospitals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2018, 52, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, F.; Üstün, B. Examination of risk assessment tools developed to evaluate risks in mental health areas: A systematic review. Nurs. Forum 2021, 56, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaimowitz, G.A.; Mamak, M.; Moulden, H.M.; Furimsky, I.; Olagunju, A.T. Implementation of risk assessment tools in psychiatric services. J. Healthc. Risk Manag. J. Am. Soc. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2020, 40, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonah, M.G.T.; Seyedsalehi, A.; Whiting, D.; Fazel, S. Violence risk assessment instruments in forensic psychiatric populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).