Abstract

This study explores how gender influences risk perception and tourist destination choice by examining the academic literature from the Web of Science and Scopus databases spanning 1995 to 2022. Through bibliometric methods, this research uncovers patterns, leading themes, and gaps in integrating gender within tourism and risk perception studies, especially during periods of heightened global risk awareness. Using bibliometric analysis, with keywords, citations, and author networks in relevant publications, co-authorship and co-citation analyses were used to identify key contributors and thematic clusters. Data visualization through VOSviewer and SCIMAT provided insights into relational trends, while alternative metrics offered a broader perspective on research dissemination and relevance. Results indicate that gender is gradually being incorporated into research on risk and tourist destination choice but remains less central than risk perception and tourism. Research in this area tends to increase in response to global crises, such as the COVID–19 pandemic. This study examines English language publications from Web of Science and Scopus, potentially limiting the generalizability of findings to non-Western contexts. By examining temporal trends, influential authors, and alternative metrics, this analysis reveals new pathways for integrating gender more fully into tourism and risk research.

1. Introduction

The success of a tourist destination lies in comprehending the factors underlying visitors’ choices and aligning policies accordingly. In this regard, numerous studies scrutinize pertinent factors influencing tourists’ decision-making processes in destination selection (Ceylan et al., 2021; Farmaki et al., 2019; Garcia et al., 2015; Hasan et al., 2017; Rosselló et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2017). Among these, risk perception plays a pivotal role in determining destination selection (Holm et al., 2017; Simpson & Siguaw, 2008; Sönmez & Graefe, 1998; Vasvári, 2015; Yang & Nair, 2014). The terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers in New York in 2001 (Karl & Schmude, 2017) and the COVID–19 pandemic (Utkarsh & Sigala, 2021) catalyzed studies increasingly focused on risk in travel decisions and their impact on destination choice. Currently, risks stemming from the climate crisis, political and social instability, terrorist attacks, and pandemics have garnered interest from both academia and tourist destinations themselves, aiming to grasp how risk perception influences travel decisions and destination choice (Jonas et al., 2011; Karl et al., 2020). Risk perception is particularly noteworthy as individual decisions are not purely rational; emotional factors also exert influence, rendering risk perception pertinent (Godovykh et al., 2021; Nazneen et al., 2020).

Understanding the nexus between risk perception and destination choice among tourists is thus instrumental in augmenting a destination’s competitiveness (Enright & Newton, 2004; Liu et al., 2019). Risk perception can be delineated as the way an individual interprets and evaluates the potential hazards or adverse outcomes associated with a specific activity or circumstance (Quintal et al., 2010; Reisinger & Mavondo, 2005). As a subjective term, risk perception is swayed by individual factors such as marital status (Fisher & Yao, 2017), demographic characteristics (Ceylan et al., 2021; Deng & Ritchie, 2018; Karl et al., 2020; Wang & Lopez, 2020), and past experiences (Michael et al., 2020; Morakabati et al., 2012; Perpiña et al., 2017), among others (Wang & Lopez, 2020).

The significance of understanding the role of personal factors in selecting a tourist destination is well recognized (Reisinger & Mavondo, 2006). Among these factors, gender has become increasingly important in both risk studies and research on destination choice (Ibanescu et al., 2018; Karl et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2020). Despite this, research on the relationship between gender, risk, and tourism remains limited and inconclusive. While some studies suggest that gender plays a substantial role in travel decision-making (Khan et al., 2020), others do not (Nuraeni & Novani, 2015). Gender is an evolving term currently gaining prominence in academic discourse, particularly with the integration of gender perspective analysis (Brown et al., 2020). Yang et al. (2017), in their bibliometric analysis, emphasized the imperative for further research in this domain, underscoring that while 67.4% of studies incorporate gender as a descriptive variable, only 10.5% focus on gender and 22.1% on women, highlighting the paucity of gender-related research in the tourism field. The importance of integrating gender into research is further supported by international public discourse, including the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 5 endeavors to achieve gender equality by advocating against discrimination regarding women, reducing women’s underrepresentation socially and politically, and empowering women and girls (United Nations, 2022).

In the context of tourism, understanding the impact of gender on risk perception and destination choice is increasingly necessary for tailoring tourism policies and product development (Afenyo-Agbe & Adeola, 2020; Aitchison, 2005; Gallego-Sosa et al., 2023; Moreno, 2017). Previous bibliometric studies have primarily focused on either the relationship between risk and tourism (Yang & Nair, 2014) or between gender and tourism (Araújo-Vila et al., 2021; Otegui-Carles et al., 2022). However, no studies have examined the intersection of these three dimensions—gender, risk, and destination choice—through a comprehensive bibliometric analysis. Understanding how these themes interconnect over time and across different research contexts is essential for identifying gaps and advancing the field. While the field has seen growing interest in mapping bibliometric trends more broadly across tourism and hospitality (Ülker et al., 2023), the lack of a structured review integrating gender, risk, and destination selection limits the ability to understand how these variables influence each other in tourism research.

To address this gap, this study conducts a bibliometric analysis of the academic literature from 1995 to 2022, allowing for the identification of key research trends and their evolution over nearly three decades. The timeframe was selected because the mid–1990s marked the beginning of bibliometric research in tourism (Yang et al., 2017), while the 2000s saw an increase in studies on risk perception following major global crises. Furthermore, recent years have introduced new research perspectives, including gendered experiences in tourism and the role of emerging risks such as climate change. By capturing this evolution, this study provides a longitudinal perspective on the interplay between gender, risk, and destination choice.

Specifically, this research seeks to achieve the following:

- Identify key trends in the academic production of this field.

- Assess the extent to which gender has been integrated into research on risk perception and tourism.

- Identify historical periods where this relationship has garnered the most academic attention.

- Analyze the influence of leading authors and institutions shaping this research area.

- Compare the results obtained by traditional and alternative metrics on gender, risk perception, and tourism destination choice research.

It seeks to identify and build upon existing knowledge, thereby advancing research in this field by highlighting both well-studied and emerging areas. This study employs bibliometric techniques to analyze research trends, identify author collaborations and networks, principal articles, and journals published on this subject, and the evolution of research in this field over time. Traditional bibliometric metrics are employed, utilizing two reputable academic databases: Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus. Despite the prevalent practice in bibliometric studies of utilizing only one database, this study utilizes both databases to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the research question, given their differential indexing of academic journals, thereby enabling the analysis of discrepancies in results between the two databases. Moreover, this study enhances traditional bibliometrics with alternative metrics, offering insights into the direct dissemination and relevance of articles through contemporary means (Agarwal et al., 2016; Priem et al., 2010). These metrics include the number of Mendeley users with an article in their personal library (Thelwall, 2017), the frequency of article mentions in blogs, press, Facebook, and Wikipedia, and the number of X publications (Ortega, 2018).

2. Materials and Methods

A bibliometric analysis, as outlined by Lievrouw (1989), was conducted to address the research objective. Bibliometric analysis was employed in this study as it is a quantitative technique that allows the examination of large volumes of the scientific literature, systematically and objectively identifying trends and structures within a field of research. Unlike other approaches, such as systematic reviews or meta-analyses, which tend to be more detailed but limited in their ability to detect broader connections, bibliometric analysis provides a comprehensive overview of academic developments in a specific discipline (Donthu et al., 2021). The bibliometric analysis is complemented by a discussion of the contents of the most-cited works

The bibliometric method examines keywords and citations in scientific publications, generating bibliometric maps, co-citation analyses, and co-authorship studies (Bar-Ilan, 2010; Li et al., 2021). It aids in identifying relevant authors, documents, and journals while assessing research trends and evolution (Koseoglu et al., 2016). In line with recent studies in the field of tourism and hospitality (Ülker et al., 2023), our analysis incorporates both evaluative techniques—such as citation and author analyses—and relational techniques, including co-word and co-author analyses, to explore relationships between key themes. This approach is increasingly utilized in tourism research, including studies on disability and accessible tourism (Qiao et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2021) and gender and tourism (Veijola, 2009; Vizcaino-Suárez & Díaz-Carrión, 2019), amongst other subareas of research.

Data Collection, Instruments, and Research Process

The traditional metrics utilized data from WoS and Scopus, renowned sources in academic and research circles, encompassing a vast array of scientific journals and articles (Qiao et al., 2022). Bibliometric methods are useful for identifying patterns and trends in each field by analyzing the academic output across time and space. To maintain rigor and focus, this study analyzed only English-written scientific articles, excluding conference proceedings and books, in line with standard practice (Vizcaino-Suárez & Díaz-Carrión, 2019). To ensure the reliability and accuracy of the data extracted from Web of Science and Scopus, several measures were applied. Firstly, a data-cleaning process was carried out to remove duplicate records and correct errors in author and institutional identification, a recommended practice in bibliometric studies to prevent biases in the results (Donthu et al., 2021). Additionally, the combination of WoS and Scopus helped mitigate the individual limitations of each database (Alsharif et al., 2022). These procedures ensure the robustness of the dataset analyzed and reinforce the validity of the findings obtained in this study.

Bibliometric maps were constructed to ascertain topic relevance and key authors, delineating thematic and author associations within the publications (Cobo et al., 2011a, 2011b; van Eck & Waltman, 2010). These maps, organized into clusters and color-coded to visualize relationships between key themes, were separately generated for WoS and Scopus due to limitations in data pooling (Cobo et al., 2011a).

To analyze the temporal evolution of themes, the SciMAT software v1.1.04 was employed, using data from WoS. SciMAT’s ability to generate strategic diagrams allowed for the identification of trends, centrality, and emerging themes over time (Casado-Aranda et al., 2021). However, Scopus data could not be utilized owing to program incompatibility.

Alternative metrics, including PlumX Metrics and Mendeley, were also employed to gauge contemporary impact and dissemination through social networks or the press (Agarwal et al., 2016; Priem et al., 2010). Mendeley data offered insights into the immediate and long-term interest generated by articles, while PlumX Metrics tracked mentions in blogs, the press, Facebook, Wikipedia, and X posts (Ortega, 2018).

The analysis covered the period from 1995 to 2022, with the bibliometric search conducted between 30 May and 12 June 2022.

3. Results

Keywords were selected by reviewing articles in both WoS and Scopus related to the research aim. Through this process, key terms frequently used in titles, abstracts, and keywords were identified. The selection of terms during the review was specific, accurate, and tailored as closely as possible to align with the research objectives.

To represent the variables to be studied, the following terms are used: gender*; risk; tourism* or travel* or destination*. These terms were chosen because they reflect the primary focus of the study and their relations within the fields of tourism, risk, and gender studies.

Only peer-reviewed scientific articles related to specific thematic areas within the thematic scope (e.g., tourism, psychology, risk) were considered, and only studies published between 1995 and 2022 were selected, ensuring a robust longitudinal analysis of trends. Additionally, a thorough review of titles was carried out to ensure that the selected articles were closely related to the topic of study.

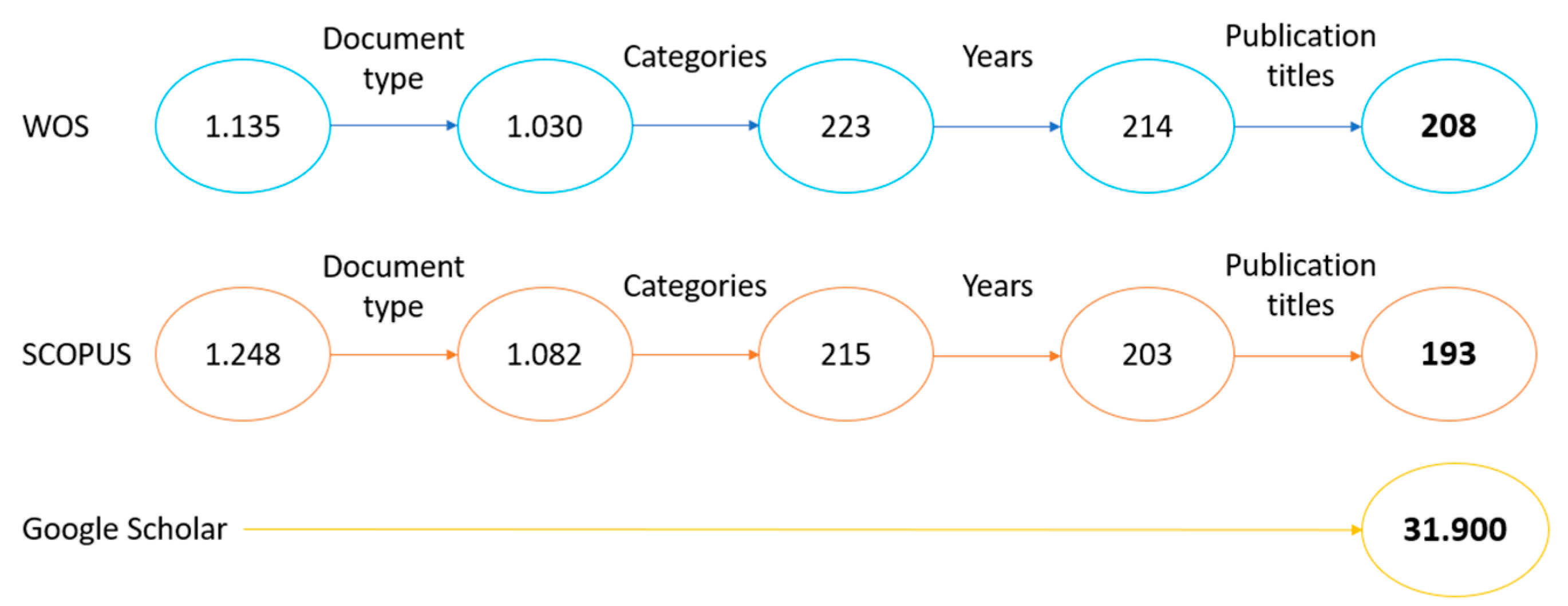

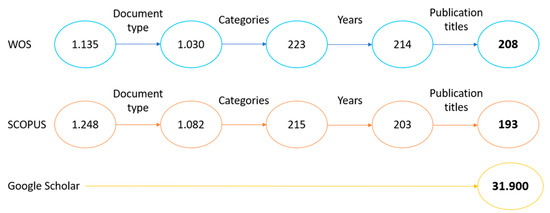

Figure 1 shows the results of the analysis process in the two databases as new search restrictions are incorporated. Ultimately, 208 articles from WoS and 193 from Scopus were selected for further analysis.

Figure 1.

Results obtained from databases. Source: information extracted from WoS and Scopus.

The analysis includes bibliometric maps and clusters via VOSViewer, journal and author analysis combined with temporal analysis and strategic diagrams using SciMat, and an examination using alternative metrics.

3.1. Traditional Metrics Analysis

3.1.1. Bibliometric Maps

Bibliometric maps were created using VOSViewer based on data from WoS and Scopus. Since VOSViewer is not customizable (Cobo et al., 2011), similar words like “risk perceptions” and “risk perception” may appear as separate terms on the maps.

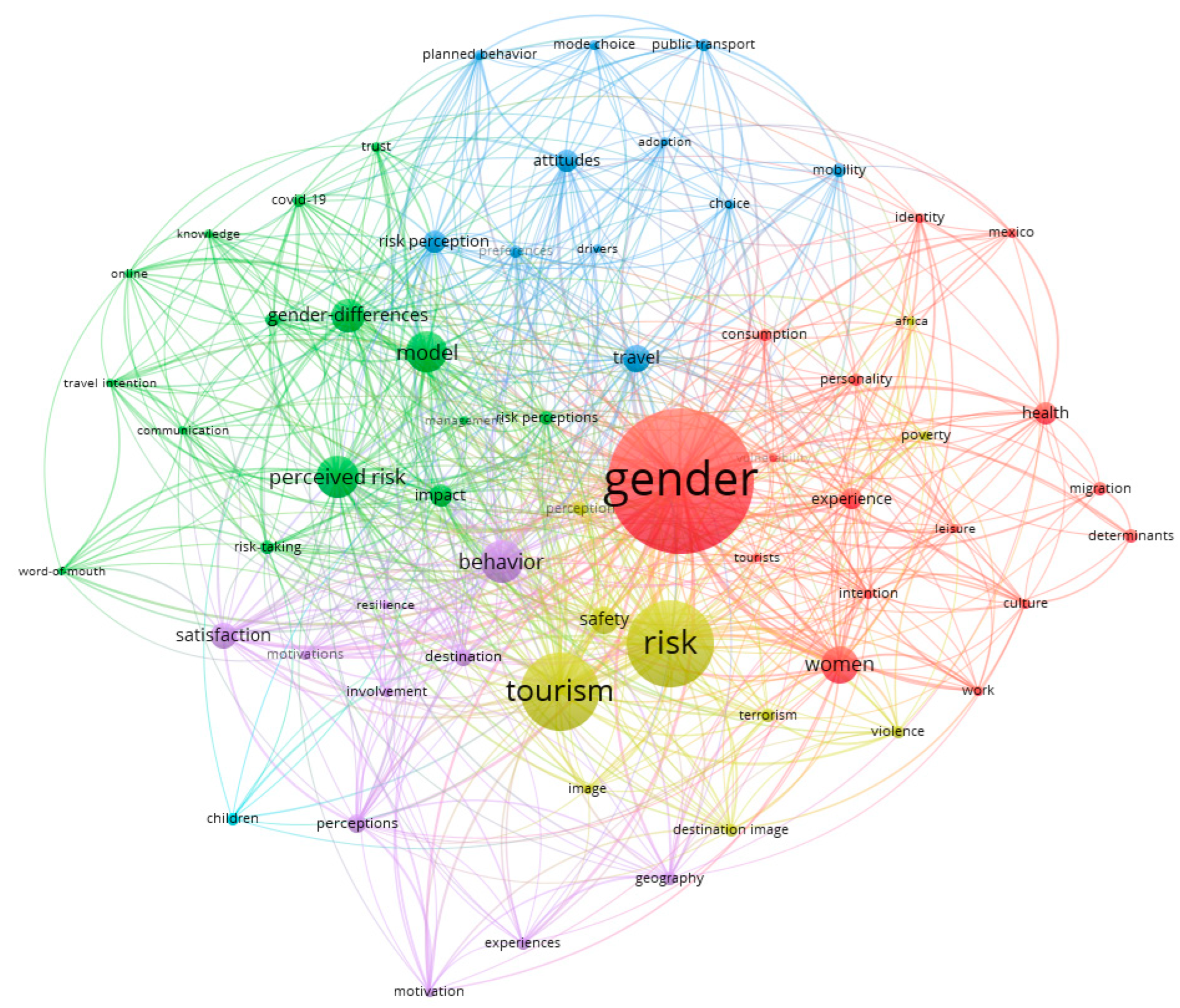

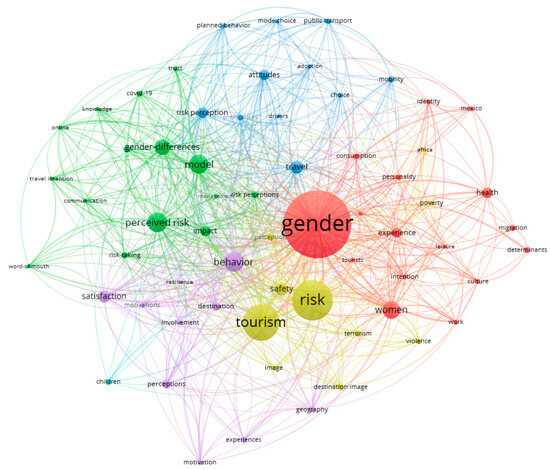

Figure 2 presents the results obtained from WoS. In the maps, larger circles indicate a greater number of articles related to the topic (Cobo et al., 2011). The bibliometric map generated from Web of Science data visually represents how key terms such as gender, tourism, and risk perception are interconnected and their frequency within the research field. Larger nodes1, such as “gender”, “tourism”, and “risk”, signify the terms most frequently addressed in the literature, with “gender” emerging as the dominant term, evidenced by its central and prominent positioning.

Figure 2.

Bibliographic map of keywords related to the relationship between risk, tourist destination, and gender from WoS. Source: own elaboration; VosViewer results from the WoS database.

Clusters are color-coded, indicating thematic groupings. The red cluster, dominated by “gender”, connects terms such as “experience”, “women”, “health”, and “migration”. This cluster focuses on studies that explore the intersection of gender roles, personal experiences, and socio-cultural dynamics. The yellow cluster centered around “tourism” and “risk”, highlights terms such as “destination image”, “safety”, and “image”, which are indicative of the literature investigating how risk perception influences tourism decision-making and destination branding. The green cluster, including “perceived risk” and “gender differences”, addresses topics related to behavioral responses and communication strategies tied to risk perception. The blue cluster, featuring terms like “travel”, “attitudes”, and “mobility”, includes research on transportation and mode choice within the tourism context. And the purple cluster, with terms like “satisfaction”, “behavior”, and “motivations”, includes studies on tourist satisfaction.

The positioning of clusters and terms highlights the interdisciplinary nature of the field. For example, while “gender” is part of a separate cluster, its proximity to “risk” and “tourism” suggests strong conceptual links, even if the research domains are not fully integrated.

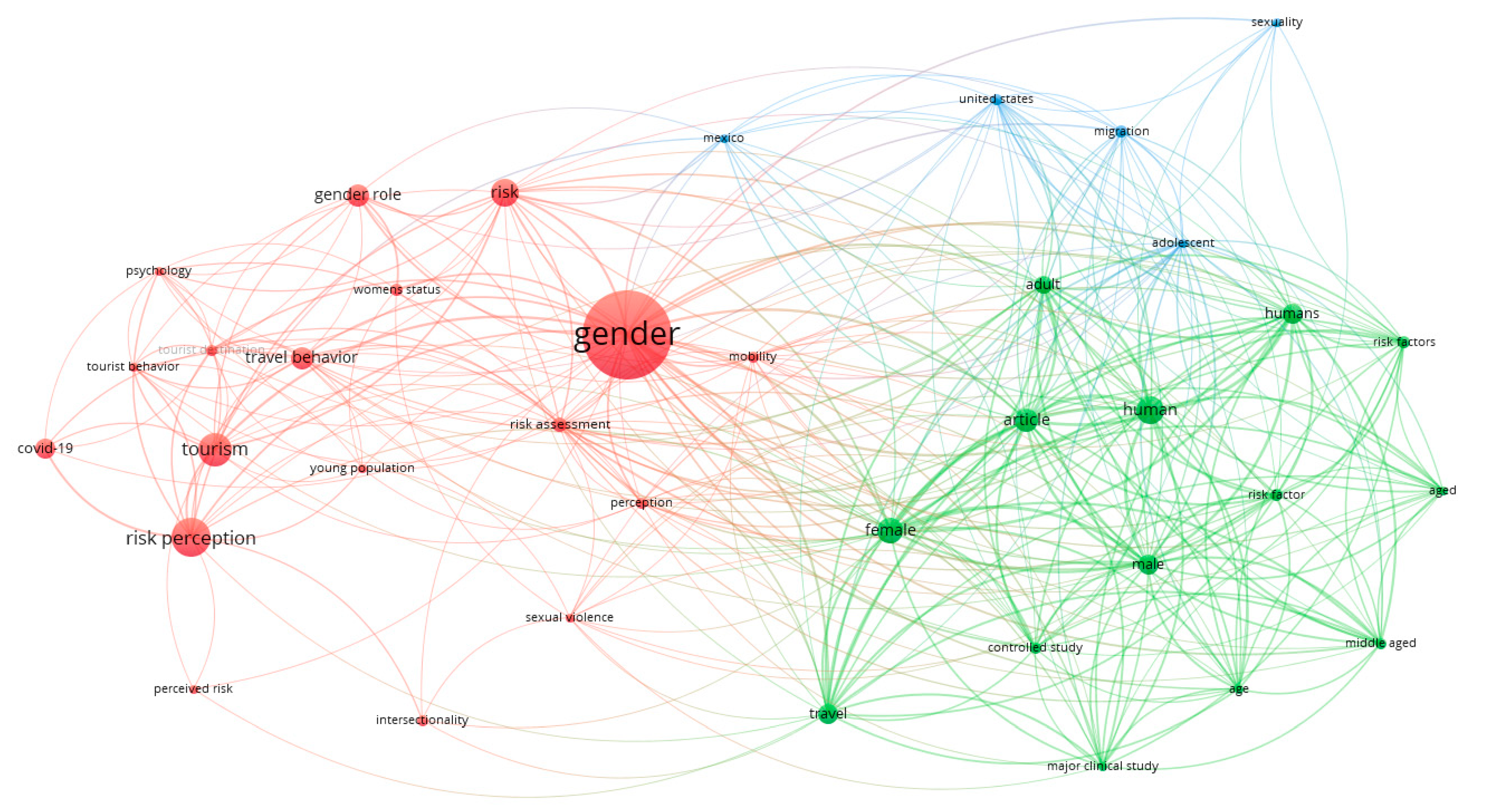

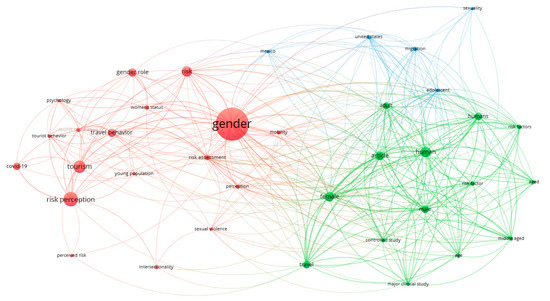

Figure 3 shows the bibliometric map generated using Scopus data that illustrates the interconnections and thematic focus within the field of gender, tourism, and risk perception. Like the Web of Science (WoS) results, the “gender” node stands out as the most prominent, indicating its central role in this body of literature. However, the Scopus results reveal some notable differences that provide additional insights into the structure of this field of research.

Figure 3.

Bibliographic map of keywords related to the relationship between risk, tourist destination, and gender from the Scopus database. Source: own elaboration; VosViewer results from the Scopus database.

The map’s clusters highlight the key patterns. The red cluster, dominated by “gender”, includes terms such as “risk perception”, “travel behavior”, and “gender role”. This cluster represents research at the intersection of gender studies and tourism-related risk behaviors. It also incorporates terms like “sexual violence” and “intersectionality”, indicating an emphasis on understanding vulnerabilities and social inequalities within the context of tourism. The green cluster focuses on demographic and methodological terms, such as “female”, “male”, “adult”, and “human”. This cluster suggests a significant portion of studies are rooted in comparative or demographic analyses, emphasizing differences in risk perception and behaviors across gender and age groups. The blue cluster includes terms like “migration”, “sexuality”, and “Mexico”, reflecting research related to socio-cultural and geographic aspects of tourism, particularly in regions with specific cultural or migratory challenges.

An analysis of the bibliometric maps generated from the WoS and Scopus databases reveals both consistent patterns and meaningful differences in the thematic structure of research on gender, tourism, and risk perception. In both databases, the terms “gender”, “tourism”, and “risk” are central to the discourse, highlighting their importance in the field. However, there are distinctions in how these concepts are interrelated.

In the WoS map (Figure 2), “gender” is isolated in its own cluster, separate from “tourism” and “risk”, which share a cluster. This suggests that research addressing gender in conjunction with these two terms may be more fragmented in the WoS-indexed literature. Conversely, in the Scopus map (Figure 3), all three terms form part of a single cluster, though the connections between them vary in intensity. This indicates that Scopus-indexed research provides a more integrated approach to the relationship between these concepts.

The relationship between “tourism” and “risk” appears stronger in both databases. In WoS, their inclusion in the same cluster underlines their thematic alignment, while in Scopus, their proximity within the same cluster reinforces this connection. This consistency suggests that these two variables are frequently studied together, reflecting a more established research focus.

Despite its prominence, “gender” appears less interconnected with “tourism” and “risk” in both maps. In WoS (Figure 2), “gender” resides in a separate cluster, reflecting a thematic separation from the other two terms. In Scopus (Figure 3), while part of the same cluster, it is positioned at a noticeable distance from “tourism” and “risk”, suggesting weaker conceptual links. This pattern implies that gender’s integration into research on risk perception and tourism is still developing despite its growing relevance in the field.

3.1.2. Journals and Author Analysis

A total of 33 journals with articles published along the research line under study were identified. Table 1 shows the nine journals with at least three articles published in either WoS or Scopus.

Table 1.

Prominent journals in the quantity of articles on tourism, risk, and gender in WoS and Scopus. Source: information extracted from WoS and Scopus.

All nine journals are reputable and positioned in the first quartile in either WoS, Scopus, or both, apart from one. The maximum number of articles in a single journal is relatively low (nine in Current Issues in Tourism), considering the long period analyzed (28 years; 1995–2022). Notably, the articles are not concentrated in a single journal but are distributed across various journals.

Initially, Wildgaard et al.’s (2014) criteria, requiring more than three publications in the research line under analysis in either WoS or Scopus, were followed to select the authors with the most citations. In this case, this criterion could not be followed as insufficient scientific production linked to the research line could be identified. Therefore, authors with more than one article published in either WoS or Scopus were considered most relevant. Among these, authors of any of the 10 most cited articles in each database were selected. This yielded eight authors (Table 2). The h-index for each author was extracted from WoS; the h-index is a metric that evaluates both the productivity and impact of a researcher. An author has an h-index of n if they have n papers cited at least n times. This metric helps measure the influence of their publications within the academic community.

Table 2.

Information on most relevant authors. Source: own elaboration.

The authors are predominantly from Western universities, with one from South Korea. Gender distribution includes five females and three males, showing broad interest. Catheryn Khoo-Lattimore and Elaine Chiao Ling Yang, from Griffith University, lead with six publications each. Charles Arcodia, also from Griffith University, co-authors with them. Liza Berdychevsky from the University of Illinois has four solo publications. An analysis of the geographical distribution of key authors highlights that most of them are affiliated with institutions in Western countries, particularly the United States and Australia. This geographical concentration suggests that much of the research on gender, tourism, and risk perception is rooted in Western academic traditions. In contrast, only one of the most cited authors, Han H., who is affiliated with Sejong University in South Korea, represents an Asian perspective.

The predominance of Western universities among the leading contributors, such as Griffith University in Australia and the University of Illinois in the USA, underscores a potential bias in the literature toward Western cultural contexts and research. Griffith University stands out as a hub for this research area, with Catheryn Khoo-Lattimore, Elaine Chiao Ling Yang, and Charles Arcodia collaborating extensively. However, the inclusion of Han H. from South Korea provides a contrasting perspective, as research in South Korea may reflect unique cultural or social dynamics that differ from those in Western nations.

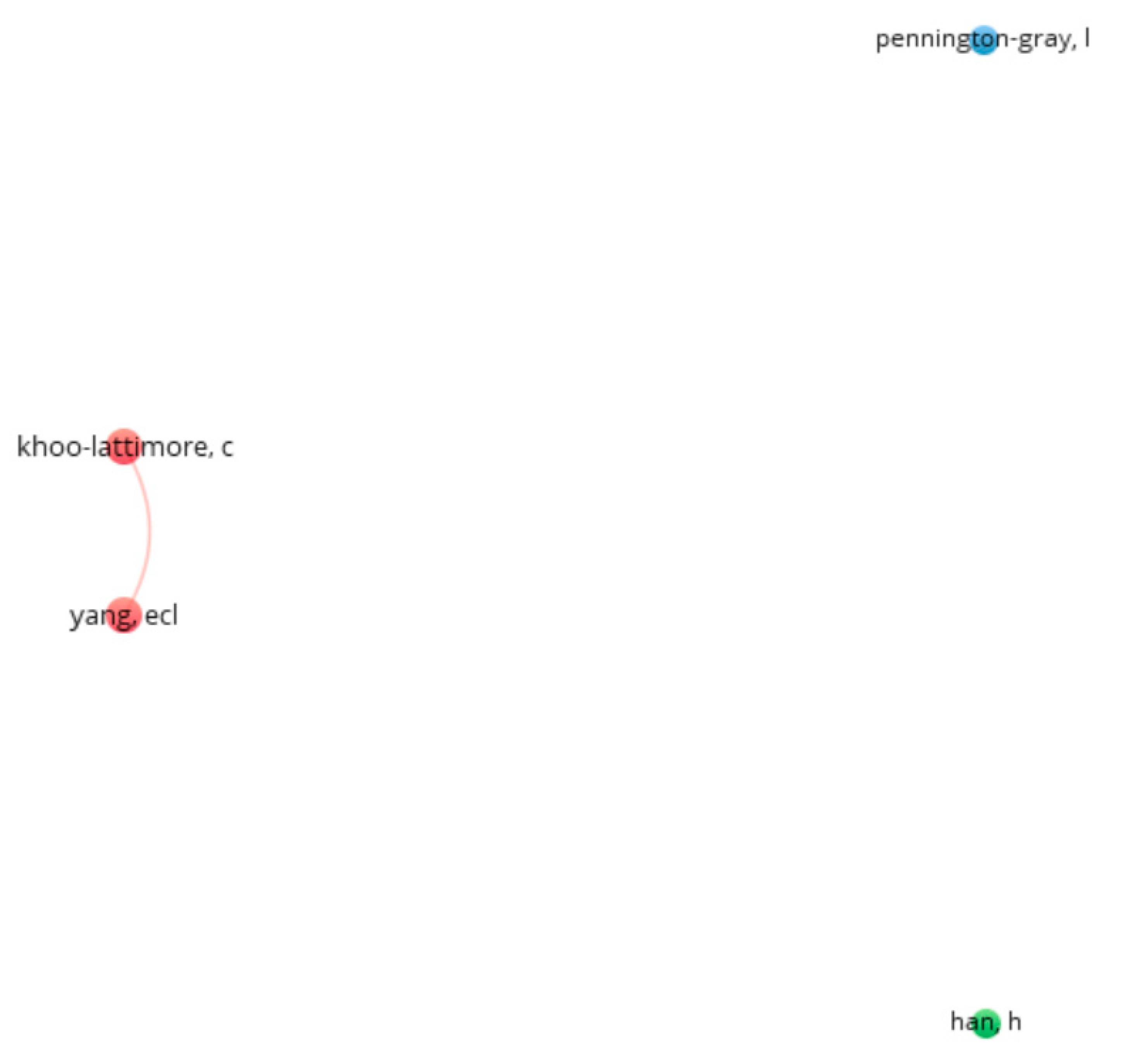

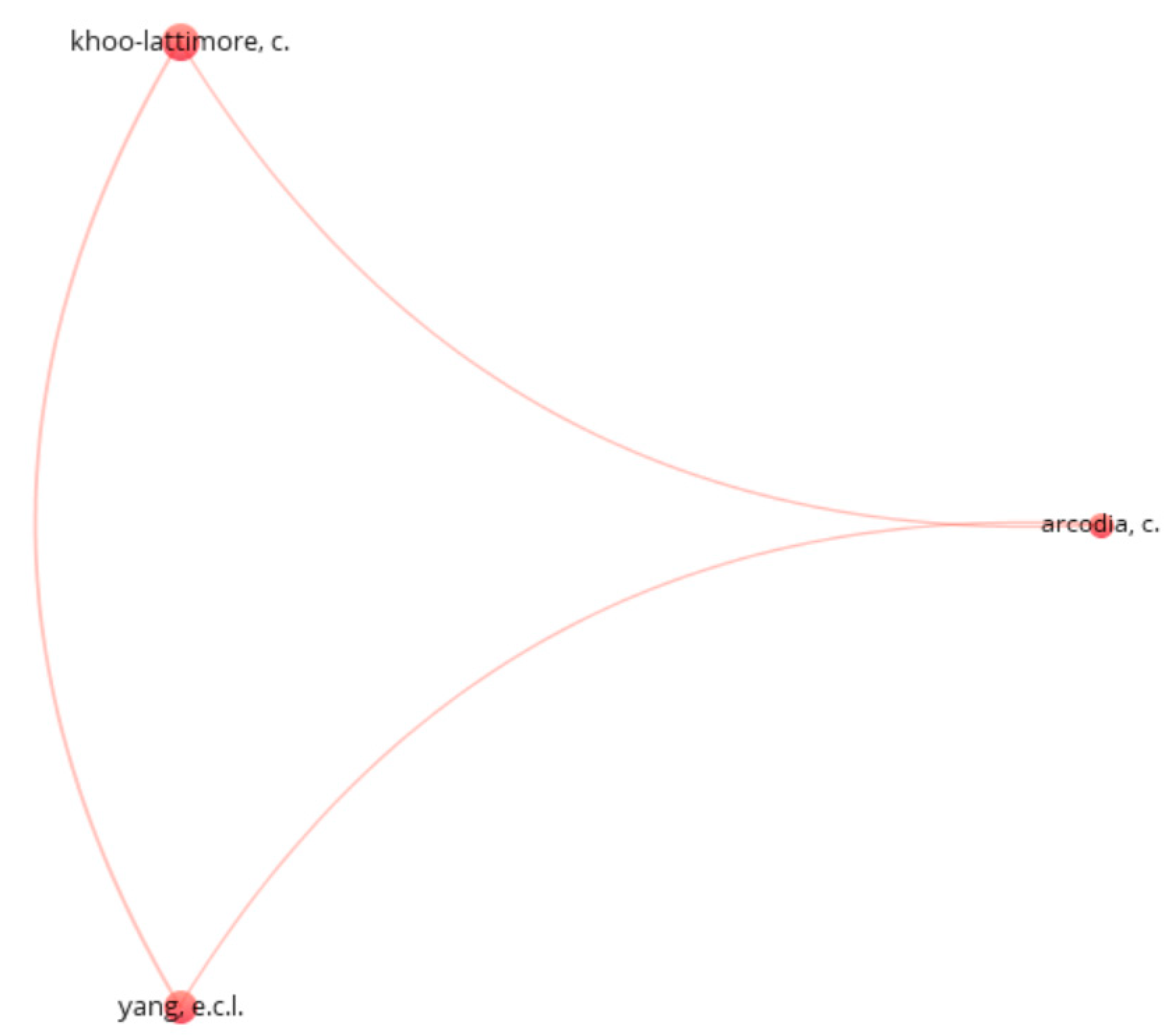

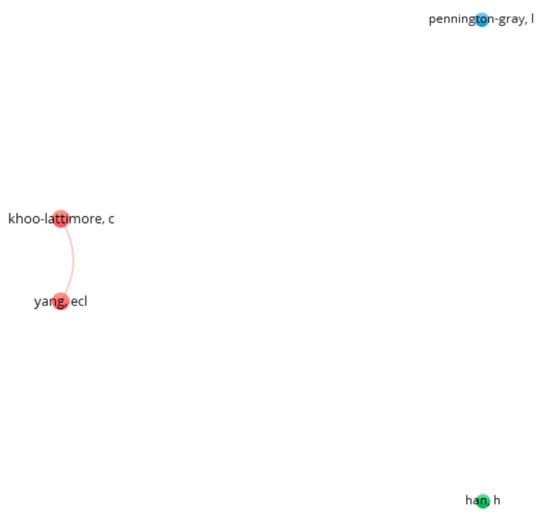

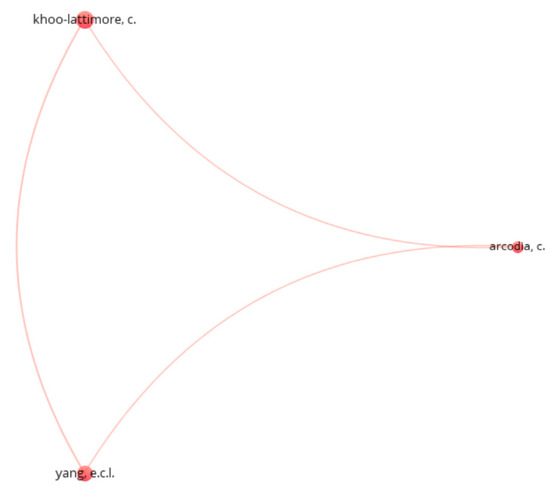

The bibliometric networks (Figure 4 and Figure 5) illustrated in the following maps provide a clear visual representation of the connections between authors in the field of tourism, risk perception, and gender. These maps highlight the collaborative relationships between scholars and the extent to which different authors have contributed to the development of the field.

Figure 4.

Bibliometric map of authors in tourism, risk perception, and gender according to Web of Science source: own elaboration; VosViewer results based on the Web of Science database.

Figure 5.

Bibliometric map of authors in tourism, risk perception, and gender according to Scopus. Source: own elaboration; VosViewer results based on the Scopus database.

The bibliometric analysis from Web of Science, shown in Figure 4, reveals a clear concentration of authors who are highly relevant in the domain of tourism, risk perception, and gender. Four authors emerge as the most frequently cited and connected. Among these, two authors stand out for their collaborative work: Khoo-Lattimore, C. and Yang, E.C.L. Notably, they have co-authored several articles, which is evident in the strong connection between their nodes in the map. Additionally, Pennington-Gray, L. and Han, H. are also prominent figures in this research area, although they are primarily represented individually on the map, with no significant co-authorship links within the scope of this study. Notably, Berdychevsky, L. does not appear in this specific map, as her publications on the topic are not present in the Web of Science database, which highlights the limitations of the database and the potential for further exploration in other repositories.

The bibliometric map obtained from the Scopus database shows a similar trend, with Khoo-Lattimore, C. and Yang, E.C.L. being the most connected and influential authors in the field. Their collaboration is reflected in the prominent position of their nodes on the map. However, a notable difference with the results obtained from the WoS database is that Arcodia, C. emerges as a key figure in the Scopus map, with a stronger connection to other authors in the network, indicating a more substantial body of work published jointly with other researchers in this domain. This highlights the importance of considering multiple databases for a more comprehensive understanding of academic influence and collaboration in the field.

Building on the bibliometric maps discussed above, Table 3 highlights the authors who have made the most significant contributions to the field in terms of citations. While the previous bibliometric maps illustrate the connections between authors and their collaborative networks, this table provides a detailed overview of the most cited articles within the scope of tourism, risk perception, and gender studies. The most cited authors not only dominate the bibliometric networks but also reflect the key trends in academic interest over time, emphasizing the foundational research and influential works that have shaped the development of this field. This further emphasizes the growing recognition of gender as a crucial factor in the study of risk perception and tourism destination choice.

Table 3.

Information on prolific and cited authors in “tourism, risk perception, and gender” according to WoS and Scopus. Source: information extracted from WoS and Scopus.

Regarding the number of citations, no author stands out significantly in this research line; Andrew Lepp is the most cited author, followed by Heather Gibson, with a citation count significantly higher than the other authors. Catheryn Khoo-Lattimore and Elaine Chiao Ling Yang stand out for having individually or jointly published a total of six articles each.

3.1.3. Temporal Evolution

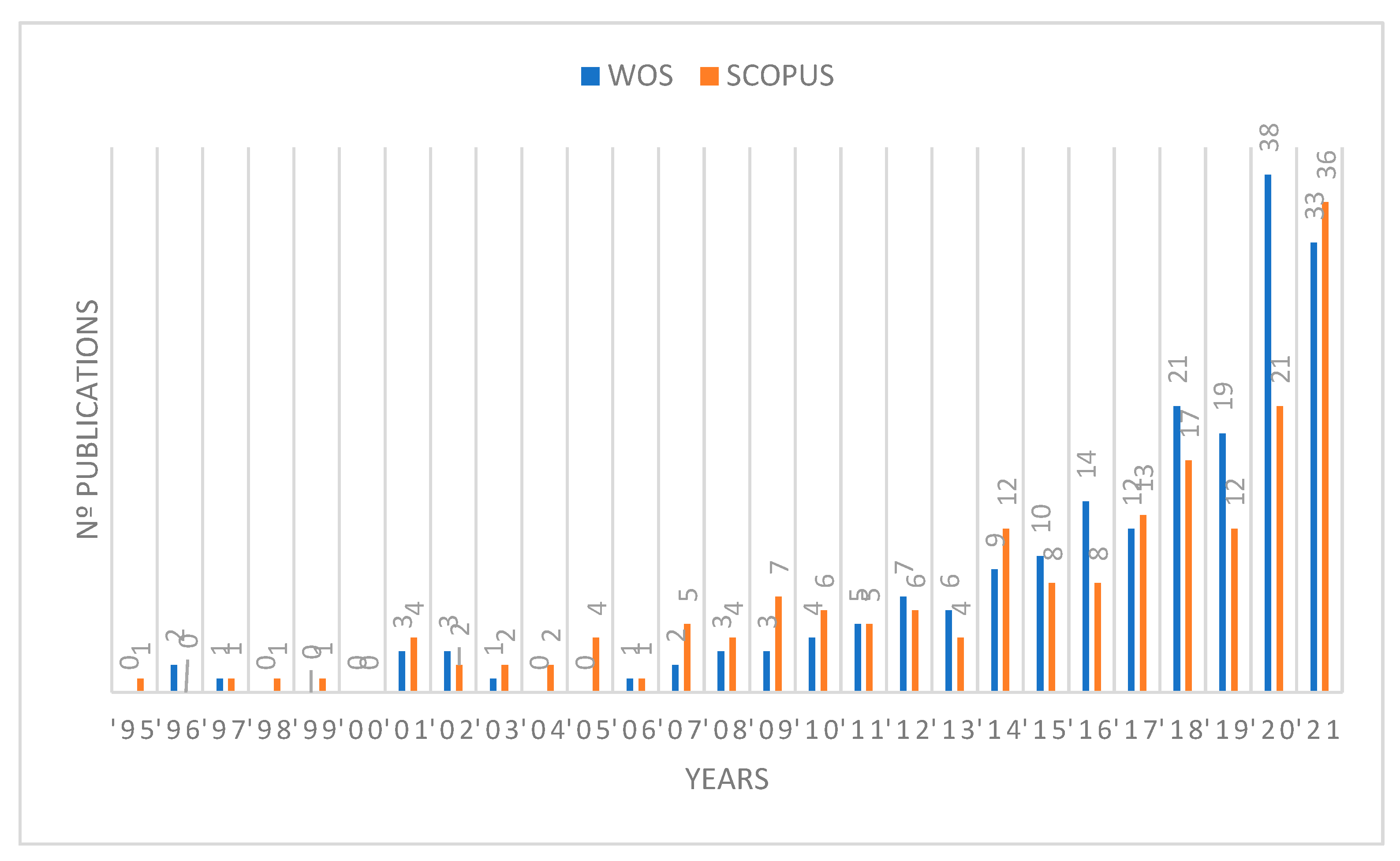

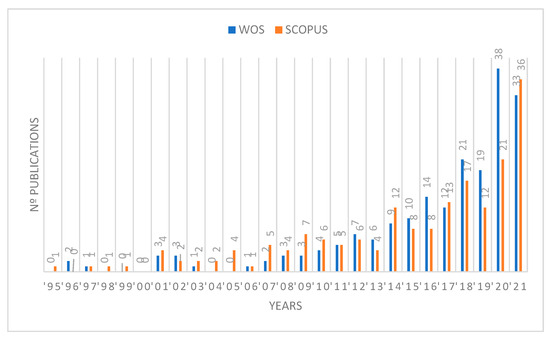

Figure 6 illustrates that articles on risk, gender, and destination first appeared in the 2000s, after which the number of articles published increased significantly. Yang et al. (2017) pointed out that several historical events have prompted interest and the publication of articles on risk and destinations, particularly the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers in New York in 2001. Furthermore, there has been a notable growing trend in the tourism sector to publish articles related to gender since 2006. The recent COVID–19 pandemic significantly impacted scientific production (Cobo et al., 2012; Utkarsh & Sigala, 2021); in 2020, 38 articles were published in WoS. In 2021, publication counts reached 33 in WoS and 36 in Scopus, marking it as the year with the highest total number of publications.

Figure 6.

Evolution of the annual number of articles in the “gender, risk, and destination” field based on WoS and Scopus. Source: own elaboration based on information extracted from WoS and Scopus.

The selected timeframe for this study, spanning from 1995 to 2022, was chosen to ensure coherence and relevance in the results. First, this period captures the theoretical and academic evolution of research on gender, risk perception, and tourism. Although significant growth in research on gender, risk perception, and tourism began in the early 2000s (Yang et al., 2017), it is essential to include earlier years to gain insight into the foundational studies and understand how this field of inquiry initially emerged and evolved. This temporal scope strikes a balance between historical evolution and current relevance, providing a solid framework to understand the dynamics of the field.

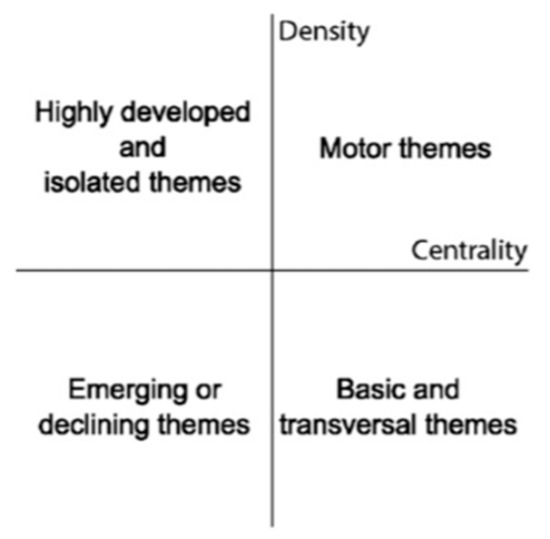

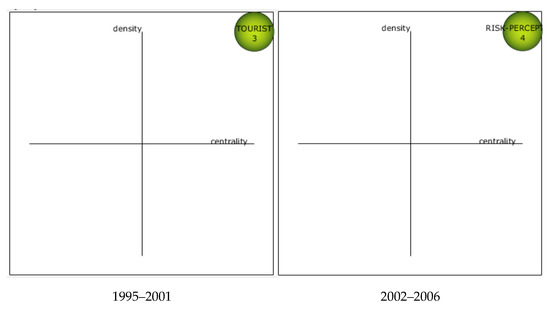

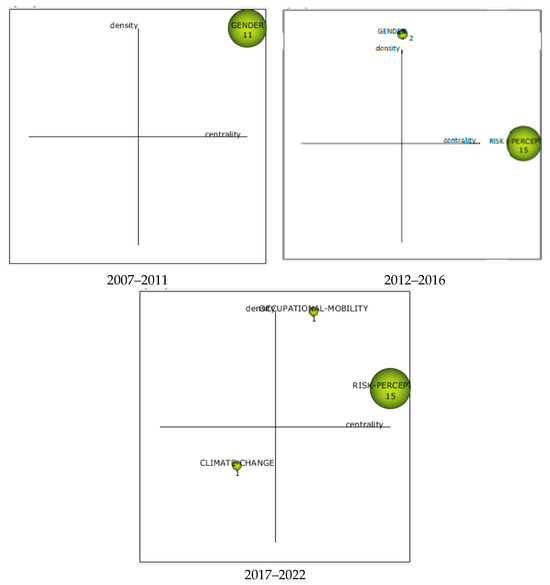

To conclude the analysis using traditional metrics, Figure 7 shows the strategic diagrams created using the SciMAT tool based on the results obtained from the WoS search (Cobo et al., 2012). These diagrams provide an overview of the evolution of the topics (Cobo et al., 2011, 2014) addressed within the topic of research on “gender, risk, and tourist destinations”. When creating the diagrams, the data were refined beforehand (Cobo et al., 2012), and authorships were unified in cases where authors were identified differently; for example, Elaine Chiao Ling Yang, identified as both “Yang, E.C.L.” and “Yang, ECL”. In this case, we opted for “Yang, E.C.L.” as a means of identification. Keywords unifying plural forms, such as “risk” and “risks”, and other purifications, such as unifying “perceived risk” and “risk perception”, were dealt with likewise.

Figure 7.

The strategic diagram. Source: Cobo et al. (2011a), p. 151.

Different subperiods were generated to observe the evolution of the topic (Cobo et al., 2011a): 1995–2001, 2002–2006, 2007–2011, 2012–2016, and 2017–2022. To analyze the highlighted themes in each subperiod, two items were considered: the size of the nodes and their location on the map (Xie et al., 2020). Node size indicates thematic impact, while node values show significance. Results’ map locations consider density and centrality. Centrality identifies influential elements, while density gauges network cohesion. High density suggests strong interconnectedness; low density indicates fragmentation. Quadrants in Figure 5 position nodes by these measures.

In addition to the size and position of the nodes, it is also worth highlighting their value and the importance of these terms over the period analyzed. In this context, the h-index (Alonso et al., 2009; Cabrerizo et al., 2010) was chosen as an indicator of the number of articles in which the terms analyzed are cited at least h times. Therefore, the numbers inside the nodes represent the h-index of each term or term in the scientific network. It is worth noting that the h-index can vary depending on the database and the set of publications used in the analysis, so the numbers inside the nodes in SciMAT will reflect the h-index calculated in the specific context of this study.

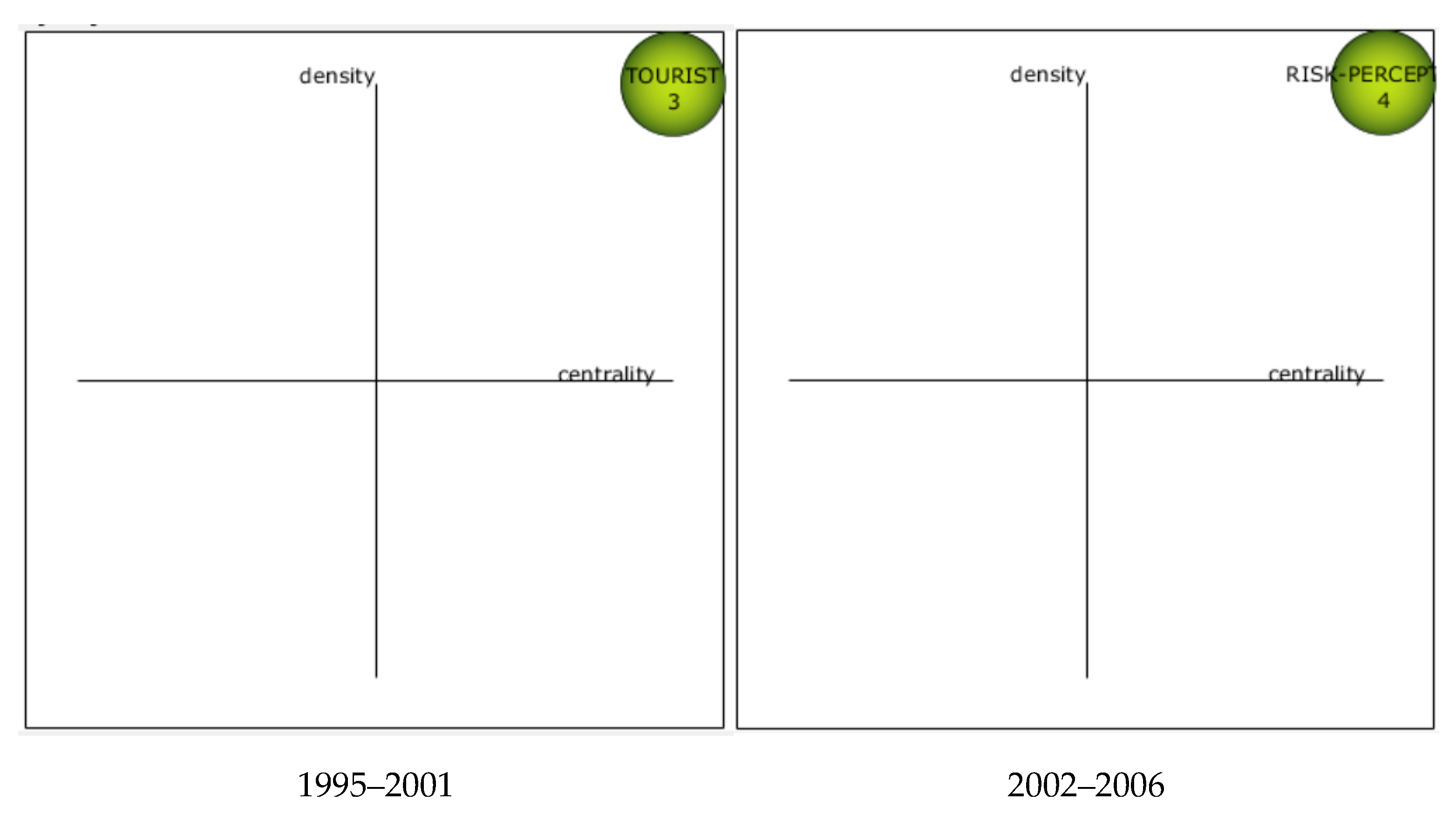

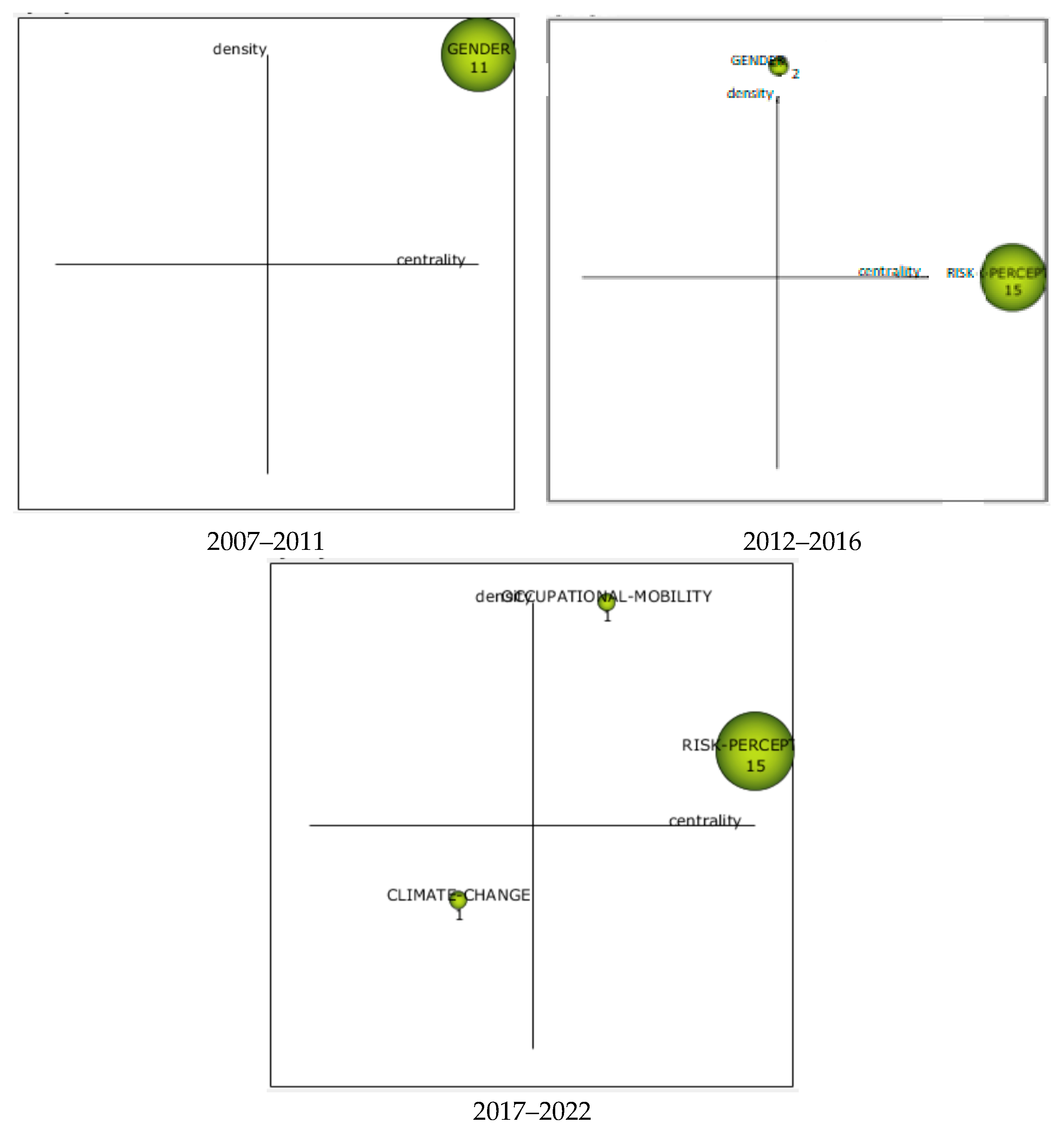

The strategic diagrams from Figure 8 illustrate how the focus has changed over the years.

Figure 8.

Strategic diagrams for periods, including 1995–2001, 2002–2006, 2007–2011, 2012–2016, and 2017–2022; data from WoS. Source: own elaboration with SciMAT based on WoS database.

Although the themes “tourism”, “risk perception”, and “gender” share the same node size and are key themes with high density and centrality, their impact varies: “tourism” has an h-index of 3, “risk perception” has an h-index of 4, and “gender” has an h-index of 11.

During the period 1995–2001, only the node “tourism” appears as a key theme. The high centrality and density indicate that it is a relevant, well-developed theme with strong internal coherence within the analyzed research field. In the period 2002–2006, the theme “risk perception” held the same position as “tourism” in the previous period, although it had a greater impact. The difference between the two periods is due to the increase in published articles after the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers (Yang et al., 2017; Yang & Nair, 2014). The 9/11 attacks triggered a global reassessment of risk, significantly influencing how destinations were perceived by travelers, leading to a surge in research focusing on risk perception and its effects on tourism choices. In the following period (2007–2011), the term “gender” is situated in the same quadrant, although the impact is much greater than the occurrence of keywords in previous periods due to its higher value. This aligns with findings by Yang et al. (2017), who claim that gender has been a growing factor in tourism research since 2006. For the period 2012–2016, no key theme was highlighted. However, the themes “risk perception” and “gender” appeared in the diagram. “Risk perception” has a greater impact as it has a larger node, high centrality, and moderate density, indicating its importance in the research field. In contrast, the “gender” theme has high density but moderate importance with average centrality. In summary, during this period, “risk perception” stands out for its impact and importance, while “gender” has high density but moderate importance in the research field. Finally, in the period 2017–2022, an increase in the impact and density of the keyword “risk perception” can be observed, indicating a closer relationship between keywords. The COVID–19 pandemic has accelerated the inclusion of health and safety concerns in tourism research, influencing the perception of risk in unprecedented ways and causing shifts in the academic discourse around travel safety and destination choice. At the same time, the “gender–risk” combination disappeared and was replaced by “occupational mobility”, which, despite having limited impact, presents higher centrality. Additionally, the emergence of a new node related to “climate change” is identified, which, despite having a reduced impact, appears as an emerging theme in the study context.

3.2. Analysis Using Alternative Metrics

The traditional metrics analysis is enhanced with an examination using alternative metrics. This study focuses on the top three cited articles in WoS and the top three in Scopus (Table 4), analyzing their usage in Mendeley and PlumX Metrics (Ortega, 2018). Mendeley tracks the number of users downloading each article for personal use, while PlumX Metrics provides data on the frequency of mentions across various platforms like blogs, press, Facebook, Wikipedia, and tweets/X (Wong & Vital, 2017).

Table 4.

Articles from the complementary analysis. Source: own elaboration.

Notably, the most downloaded articles on Mendeley, by tom Dieck and Jung (2018) and Yang et al. (2017), differ from the most cited in WoS and Scopus. Social media dissemination is generally low, with key articles like Sönmez and Graefe (1998) and Yang et al. (2017) scarcely mentioned. Even on platforms like X, some articles have only a few mentions, such as tom Dieck and Jung (2018) and Lepp and Gibson (2003, 2008). Facebook sees slightly higher engagement, particularly with articles like Elsrud (2001) and Lepp and Gibson (2003).

While Mendeley downloads often correlate with citations, exceptions exist. For instance, “A theoretical model of mobile augmented reality acceptance in urban heritage tourism” garnered significant Mendeley reads but fewer Scopus and WoS citations, possibly due to its introduction of virtual reality as a new trend. Conversely, social media mentions are generally lower. Standout examples include “Risk creation in traveling—Backpacker adventure narration” on Facebook and “Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism”. Thus, alternative metrics may not fully capture immediate or growing interest in contemporary topics.

The selected articles provide a comprehensive overview of key topics related to tourism, risk perception, gender differences, and decision-making in travel behavior. A recurring theme across these studies is the dual role of risk: while it can act as a deterrent for some travelers, it is also sought out and even romanticized by others, particularly in adventure and backpacker tourism.

“Risk creation in traveling—Backpacker adventure narration” (Elsrud, 2001) explores how backpackers actively construct and narrate risk as part of their travel experiences. The study reveals that risk-taking is often romanticized and socially valued within the backpacker subculture, reinforcing adventure tourism as a site of identity formation. This contrasts with “Influence of terrorism risk on foreign tourism decisions” (Sönmez & Graefe, 1998), which highlights how perceived risk—particularly in the form of terrorism—can act as a deterrent to travel. This divergence suggests that risk perception is highly contextual: while some travelers embrace risk as part of self-discovery, others see it as a critical factor to be mitigated or avoided entirely.

The interplay between risk and individual travel styles is further examined in “Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism” (Lepp & Gibson, 2003). This study finds that explorers and drifters who seek novelty and adventure perceive less risk than mass tourists, indicating that personal travel styles significantly shape destination preferences. A later study by the same authors, “Sensation seeking and tourism: Tourist role, perception of risk and destination choice” (Lepp & Gibson, 2008), expands on this idea, demonstrating that sensation-seeking tourists are more likely to travel internationally and to destinations perceived as risky. However, in contrast to other studies, they found no significant gender differences in risk perception, suggesting that personal traits rather than gender alone may be a stronger determinant of risk-related travel behaviors.

The influence of gender in shaping travel experiences and risk perception is another crucial dimension explored in these studies. Lepp and Gibson (2008) question that gender alone predicts risk-taking, “A systematic literature review of risk and gender research in tourism” (Yang et al., 2017) suggests that gender remains a key variable in tourism research but is often treated superficially. They highlight that most studies use gender as a statistical descriptor rather than exploring its deeper socio-cultural implications, calling for future research to move beyond binary comparisons.

Additionally, the role of technology in risk perception and decision-making adds another dimension to this discussion. “A theoretical model of mobile augmented reality acceptance in urban heritage tourism” (tom Dieck & Jung, 2018) examines how augmented reality (AR) influences travel experiences. Although not directly focused on risk or gender, this study provides an important perspective on how digital tools may help travelers manage risk perception. AR offers real-time, immersive information, which can increase feelings of security and control, particularly for risk-averse tourists. This insight aligns with broader discussions on how risk perception is shaped not only by personal factors but also by external influences such as technological advancements.

Taken together, these studies illustrate the complex and multifaceted nature of risk perception and gender in tourism. Rather than viewing risk solely as an objective threat, these studies demonstrate how risk is both socially constructed and individually negotiated.

A significant takeaway from this body of research is the need for a more critical and theoretical approach to studying risk and gender in tourism. Yang et al. (2017) said that much of the existing literature remained limited in theoretical scope, often relying on descriptive statistics rather than deeper socio-cultural analyses. They call for future studies to explore how gender and risk intersect, considering factors such as identity, cultural expectations, and power structures, and should adopt a more intersectional approach, considering how different variables, such as age, cultural background, and digital literacy, measure the perception and management of travel risk.

4. Discussion

This study analyzes the production of academic articles related to how gender influences risk perception and choice of tourist destinations, using bibliometric analysis techniques to explore the hypothetical relationship between these factors.

General findings indicate that research on the relationship between gender and risk perception is still in its early stages, with gender only recently being incorporated into studies on tourist destination risk perception. However, the findings suggest that gender is becoming an increasingly significant variable in contemporary research. The bibliometric maps provide further insight into this trend. In the WoS map (Figure 2), “gender” appears in an isolated cluster, separate from “tourism” and “risk”, which are more closely linked. This fragmentation suggests that research integrating gender with risk perception and tourism remains underdeveloped in the WoS-indexed literature. Conversely, in the Scopus map (Figure 3), all three terms form part of the same cluster, with varying degrees of connection. This contrast between the two databases implies that while gender is increasingly acknowledged in tourism and risk research, its level of integration differs depending on the scholarly sources considered.

Furthermore, our analysis reveals that publications combining these three terms—gender, risk, and tourism—tend to increase during periods of heightened risk perception, such as during terrorist attacks or the COVID–19 pandemic. This demonstrates a temporal correlation between global crises and an increased academic focus on the relationship between these terms.

Regarding the selection of the most prolific and relevant authors, Wildgaard et al.’s (2014) proposed methodology could not be followed because there was insufficient scientific production related to the line of research. This is even though the number of published and cited articles demonstrates this is a growing field of study. Therefore, authors who have more than one article published in WoS or Scopus and who authored some of the ten most cited articles in each database were considered the most relevant. The most important of these authors are Arcodia, C., Berdychevsky, L., Gibson, H.J., Han H., Khoo-Lattimore, C., Lepp, A., Pennington-Gray, L., and Yang, E.C.L., all affiliated with Western universities and English-speaking countries (Australia and the United States), except for one, which is affiliated with an Eastern university (South Korea). This bias may be because the articles reviewed are exclusively in English or due to the scientific or cultural policies in other countries where this topic is not yet relevant. In this respect, the content analysis study of scientific articles on tourism, gender, and risk by Yang et al. (2017) suggests that research is highly concentrated in geographical terms. This geographical concentration might reflect the dominance of English in academic publishing, as well as differing scientific priorities or cultural policies in other regions.

Regarding the temporal evolution of the study on the terms analyzed, a trend in the initial period showed that the study terms stood out separately in this order: first, tourist destination, then risk perception, followed by gender, and finally, a combination of several terms, such as risk perception and gender.

The temporal analysis of the strategy diagrams reveals a shift in the research conducted in these areas. During the period 1995–2001, tourism emerged as the most prominent research topic, indicating a strong focus on this area of investigation. From 2002 to 2006, risk perception gained prominence as the dominant topic (Yang et al., 2017; Yang & Nair, 2014). Subsequently, from 2007 to 2011, gender became the most important topic (Yang et al., 2017). The period from 2012 to 2016 is marked by a diversification in the significance of the study topic, with a particular emphasis on the relationship between gender and risk. Notably, in the latter part of this period, the inclusion of variables not directly related to the article’s main topic was observed, suggesting a link between climate change and risk perception.

An additional objective of the study was to complement traditional metrics with alternative metrics to assess the contemporary impact and dissemination of articles on social media platforms. The analysis indicates that there is little difference between alternative and traditional metrics in terms of assessing article impact, suggesting that the conventional approach remains valid.

In conclusion, this study confirms an upward trend in research exploring the relationships between tourism, risk perception, and gender. Tourism has traditionally been the focal point of study, with risk perception being integrated over time. Now, gender is gradually being incorporated into these discussions. This growth highlights the evolving nature of academic inquiry in these fields and suggests that future research will continue to explore the role of gender in shaping perceptions of risk within the context of tourism.

5. Conclusions

This study has provided a comprehensive analysis of the evolution of the relationship between gender, risk perception, and tourism destination choice through bibliometric techniques from 1995 to 2022. The findings show how these variables have been incorporated into the academic literature, as well as emerging patterns in the study of this theme. Firstly, we identified key trends in the academic production of this field, highlighting significant growth in recent years. Secondly, we examined how gender has been progressively integrated into research on risk perception and tourism, with a notable increase following certain global events, such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the COVID–19 pandemic. Thirdly, we observed historical periods where this relationship has received the most academic attention, providing a clear temporal context for our findings.

In line with the initial objectives, this study has provided a detailed analysis of the development of research on these key themes, offering new contributions to the existing literature. By examining publications between 1995 and 2022, we identified significant shifts in the focus of researchers, particularly regarding the inclusion of gender in discussions of risk perception and tourism destination choice. Concerning the key authors and institutions, we found a geographical concentration in English-speaking countries, apart from one author from South Korea. This highlights the need to foster a more diverse global discussion on these topics. Finally, the analysis of traditional and alternative metrics suggested that the dissemination of studies via social media platforms is playing an increasingly prominent role, a trend that is likely to continue growing in the future.

This study contributes to the existing literature in multiple ways. First, it bridges a gap in research by systematically analyzing the intersection of gender, risk perception, and tourism destination choice—three concepts that have been studied separately but rarely in combination. While previous bibliometric studies have explored the relationship between risk and tourism (Yang & Nair, 2014) or gender and tourism (Araújo-Vila et al., 2021; Otegui-Carles et al., 2022), this research is the first to comprehensively examine all three dimensions together.

Second, by employing both Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus, this study enhances the robustness of bibliometric findings, addressing potential biases that arise from relying on a single database. Furthermore, the inclusion of altimetric indicators offers a complementary perspective by illustrating how academic studies in this area gain visibility and engagement beyond traditional citation metrics, particularly through digital and social media platforms.

Finally, this study uncovers temporal patterns, showing that interest in gender and risk perception in tourism spikes during periods of heightened global uncertainty, such as terrorist attacks and pandemics. This finding suggests that external crises catalyze research in this domain, reinforcing the need for continued scholarly attention to these themes.

The findings of this study have significant implications for destination marketers (Lepp & Gibson, 2008; Sönmez & Graefe, 1998) and crisis management planning within the tourism industry. Since gender plays a crucial role in shaping risk perception, marketing strategies should be tailored to address the distinct concerns of male and female travelers (Lepp & Gibson, 2003; tom Dieck & Jung, 2018). Therefore, tourism campaigns should emphasize gender-sensitive practices (F. Meng & Uysal, 2008), such as enhanced safety measures, women-friendly accommodations, and accessible emergency support. By highlighting these features in promotional materials, tourism destinations can increase their appeal to female travelers, ultimately boosting tourism numbers.

Furthermore, the study underscores the need for integrating gender-specific considerations into crisis management and resilience planning. The increased relevance of gender during global crises, such as pandemics or terrorist attacks, calls for tourism destinations to include gender-sensitive elements in their emergency response plans. This involves tailoring emergency services and communications to meet the needs of both male and female tourists. Ensuring that health and safety protocols address gender-specific concerns, such as providing specialized evacuation routes, accessible healthcare services, and targeted communication during crises, can help build trust and confidence among travelers. This approach not only enhances the security of tourists but also strengthens the overall resilience of destinations in times of crisis.

This study provides a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of the intersection between gender, risk perception, and tourist destination choice, mapping the evolution of these themes from 1995 to 2022. However, given the dynamic nature of tourism and the external factors influencing travel decisions, future research should expand upon these findings to track further developments in the field. One of the most pertinent avenues for future research is to continue this analysis beyond 2022, especially considering the significant societal and global shifts in recent years. By focusing on post–2022 publications, future studies can assess how these global challenges continue to affect the relationship between gender, risk, and destination choice, providing insights into the long-term changes in tourism trends.

Another area for further investigation is the integration of other variables, such as technological innovations (e.g., digital tourism tools) and their impact on risk perception. The role of emerging technologies in enhancing tourist safety perceptions could offer a valuable addition to the existing literature, particularly in relation to gendered experiences in travel. Furthermore, future research could explore the influence of newer global risks, such as the rise of artificial intelligence and cybersecurity concerns, on tourists’ decision-making processes. Moreover, this study has analyzed two major global events—9/11 and COVID–19—that have had a considerable effect on the risk perception and the research of tourism. In the future, additional studies could test this idea against new crises, such as the Ukraine–Russia and Israel–Palestine conflicts, to see how they affect travel behavior and the destination risk perception literature.

This study contributes significantly to the analysis of the role of gender in risk perception and destination selection.

Author Contributions

M.A.-M., E.C.L. and E.M.-G., Conceptualization and methodology, M.A.-M., software, M.A.-M. and E.C.L., validation and formal analysis, M.A.-M., E.C.L. and E.M.-G., resources, M.A.-M. and E.M.-G., investigation, M.A.-M., writing—original draft preparation, M.A.-M., E.C.L. and E.M.-G., writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

E. Martinez-Garcia contribution was funded by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation grant number PID2020-117459RB-C21.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Nodes represent keywords or terms within the research field, with their size indicating frequency of occurrence. |

References

- Afenyo-Agbe, E. A., & Adeola, O. (2020). Promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment through tourism in africa: Towards agenda 2030. In O. Adeola (Ed.), Empowering african women for sustainable development (pp. 121–132). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A., Durairajanayagam, D., Tatagari, S., Esteves, S. C., Harlev, A., Henkel, R., Roychoudhury, S., Homa, S., Puchalt, N. G., Ramasamy, R., Majzoub, A., Ly, K. D., Tvrda, E., Assidi, M., Kesari, K., Sharma, R., Banihani, S., Ko, E., Abu-Elmagd, M., Gosalvez, J., Bashiri, A. (2016). Bibliometrics: Tracking research impact by selecting the appropriate metrics. Asian Journal of Andrology, 18(2), 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitchison, C. C. (2005). Feminist and gender perspectives in tourism studies: The social-cultural nexus of critical and cultural theories. Tourist Studies, 5(3), 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, A., Olya, H. G. T., & Han, H. (2019). Effect of general risk on trust, satisfaction, and recommendation intention for halal food. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 83, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almathami, R., Khoo, C., & Yang, E. C. L. (2021). Enablers for empowerment: Saudi women’s employment in the events sector. Tourism Recreation Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, S., Cabrerizo, F. J., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2009). h-Index: A review focused in its variants, computation and standardization for different scientific fields. Journal of Informetrics, 3(4), 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A. H., Salleh, N. Z. M., Baharun, R., Abuhassna, H., & Hashem, A. R. (2022). A global research trends of neuromarketing: 2015–2020. Revista de Comunicación, 21(1), 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo-Vila, N., Otegui-Carles, A., & Fraiz-Brea, J. A. (2021). Seeking Gender Equality in the Tourism Sector: A Systematic Bibliometric Review. Knowledge, 1(1), 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Ilan, J. (2010). Citations to the ‘Introduction to informetrics’ indexed by WOS, Scopus and Google Scholar. Scientometrics, 82, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdychevsky, L. (2016). Antecedents of young women’s sexual risk taking in tourist experiences. Journal of Sex Research, 53(8), 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdychevsky, L. (2017a). Sexual health education for young tourists. Tourism Management, 62, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdychevsky, L. (2017b). Toward the tailoring of sexual health education messages for young women: A focus on tourist experiences. Journal of Sex Research, 54(9), 1171–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdychevsky, L., & Gibson, H. J. (2015). Phenomenology of young women’s sexual risk-taking in tourism. Tourism Management, 46, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L., de Coteau, D., & Lavrushkina, N. (2020). Taking a walk: The female tourist experience. Tourist Studies, 20(3), 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrerizo, F. J., Alonso, S., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2010). q 2-Index: Quantitative and qualitative evaluation based on the number and impact of papers in the hirsch core. Journal of Informetrics, 4, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanto, I., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2015). Communicating hurricane evacuation to tourists: Gender, past experience with hurricanes, and place of residence. Journal of Travel Research, 54(3), 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanto, I., Wiblishauser, M., Pennington-Gray, L., & Schroeder, A. (2016). The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the U.S. Tourism Management Perspectives, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado-Aranda, L. A., Sánchez-Fernández, J., & Viedma-del-Jesús, M. I. (2021). Analysis of the scientific production of the effect of COVID–19 on the environment: A bibliometric study. Environmental Research, 193, 110416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, D., Çizel, B., & Karakaş, H. (2021). Destination image perception patterns of tourist typologies. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(3), 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X., Cai, G., & Han, H. (2021). Festival travellers’ pro-social and protective behaviours against COVID-19 in the time of pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(22), 3256–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M. J., Chiclana, F., Collop, A., De Ona, J., & Herrera-Viedma, E. (2014). A bibliometric analysis of the intelligent transportation systems research based on science mapping. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 15(2), 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2011a). An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the Fuzzy Sets Theory field. Journal of Informetrics, 5, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2011b). Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(7), 1382–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M. J., Lõpez-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2012). SciMAT: A new science mapping analysis software tool. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(8), 1609–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera Viedma, E., & Herrera Triguero, F. (2011). SciMAT: Herramienta software para El análisis de La evolución Del conocimiento científico. Propuesta de Una Metodología de Evaluación, Universidad de Granada. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R., & Ritchie, B. W. (2018). International university students’ travel risk perceptions: An exploratory study. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(4), 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsrud, T. (2001). Risk creation in traveling: Backpacker adventure narration. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(3), 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, M. J., & Newton, J. (2004). Tourism destination competitiveness: A quantitative approach. Tourism Management, 25, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, A., Khalilzadeh, J., & Altinay, L. (2019). Travel motivation and demotivation within politically unstable nations. Tourism Management Perspectives, 29, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, P. J., & Yao, R. (2017). Gender differences in financial risk tolerance. Journal of Economic Psychology, 61, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Sosa, C., Fernández-Torres, Y., & Gutiérrez-Fernández, M. (2023). The 2030 Agenda and sustainable development in tourism firms: Board gender diversity and environmental policy on natural resource use. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(1), 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J., Juaneda, C., Raya, J. M., & Sastre, F. (2015). A study of traveller decision-making determinants: Prioritizing destination or travel mode? Tourism Economics, 21(6), 1149–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M., Pizam, A., & Bahja, F. (2021). Antecedents and outcomes of health risk perceptions in tourism, following the COVID–19 pandemic. Tourism Review, 76(4), 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. K., Ismail, A. R., & Islam, M. F. (2017). Tourist risk perceptions and revisit intention: A critical review of literature. Cogent Business and Management, 4(1), 1412874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, M. R., Lugosi, P., Croes, R. R., & Torres, E. N. (2017). Risk-tourism, risk-taking and subjective well-being: A review and synthesis. Tourism Management, 63, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanescu, B. C., Stoleriu, O. M., & Gheorghiu, A. (2018). Gender differences in tourism behaviour in the European Union. Eastern Journal of European Studies, 9(1), 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, A., Mansfeld, Y., Paz, S., & Potasman, I. (2011). Determinants of health risk perception among low-risk-taking tourists traveling to developing countries. Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, M., Muskat, B., & Ritchie, B. W. (2020). Which travel risks are more salient for destination choice? An examination of the tourist’s decision-making process. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 18, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, M., & Schmude, J. (2017). Understanding the role of risk (perception) in destination choice: A literature review and synthesis. Tourism, 65(2), 138–155. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. A., Rana, I. A., & Nawaz, A. (2020). Gender-based approach for assessing risk perception in a multi-hazard environment: A study of high schools of Gilgit, Pakistan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 44, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Schroeder, A., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2016). Does culture influence risk perceptions? Tourism Review International, 20, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, M. A., Rahimi, R., Okumus, F., & Liu, J. (2016). Bibliometric studies in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 61, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A., & Gibson, H. (2003). Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A., & Gibson, H. (2008). Sensation seeking and tourism: Tourist role, perception of risk and destination choice. Tourism Management, 29(4), 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Goerlandt, F., & Reniers, G. (2021). An overview of scientometric mapping for the safety science community: Methods, tools, and framework. Safety Science, 134, 105093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievrouw, L. A. (1989). The invisible college reconsidered: Bibliometrics and the development of scientific communication theory. Communication Research, 16(5), 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Cheng, P., & OuYang, Z. (2019). Disaster risk, risk management, and tourism competitiveness: A cross-nation analysis. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B., & Han, H. (2018). Investigating individuals’ decision formation in working-holiday tourism: The role of sensation-seeking and gender. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 35(8), 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F., & Uysal, M. (2008). Effects of gender differences on perceptions of destination attributes, motivations, and travel values: An examination of a nature-based resort destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(4), 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, N., Nyadzayo, M. W., Michael, I., & Balasubramanian, S. (2020). Differential roles of push and pull factors on escape for travel: Personal and social identity perspectives. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(4), 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morakabati, Y., Fletcher, J., & Prideaux, B. (2012). Tourism development in a difficult environment: A study of consumer attitudes, travel risk perceptions and the termination of demand. Tourism Economics, 18(5), 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, D. (2017). Turismo y Género: Un enfoque esencial en un contexto de desarrollo sostenible y responsable del turismo [Thesis doctoral no publicada, Universidad Complutense de Madrid]. [Google Scholar]

- Mura, P., & Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2012). Young tourists, gender and fear on holiday. Current Issues in Tourism, 15(8), 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazneen, S., Hong, X., & Ud Din, N. (2020). COVID–19 crises and tourist travel risk perceptions. SSRN Electronic Journal, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuraeni, S., & Novani, S. (2015). Understanding consumer decision-making in tourism sector: Conjoint analysis. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 169, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J. L. (2018). Reliability and accuracy of altmetric providers: A comparison among Altmetric.com, PlumX and Crossref Event Data. Scientometrics, 116, 2123–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otegui-Carles, A., Araújo-Vila, N., & Fraiz-Brea, J. A. (2022). Solo travel research and its gender perspective: A critical bibliometric review. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(3), 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpiña, L., Prats, L., & Camprubí, R. (2017). Investigating perceived risks in international travel. Tourismos, 12(2), 104–132. [Google Scholar]

- Priem, J., Taraborelli, D., Groth, P., & Neylon, C. (2010). Altmetrics: A manifesto. Available online: http://altmetrics.org/manifesto/ (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Qiao, G., Ding, L., Zhang, L., & Yan, H. (2022). Accessible tourism: A bibliometric review (2008–2020). Tourism Review, 77(3), 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintal, V. A., Lee, J. A., & Soutar, G. N. (2010). Risk, uncertainty and the theory of planned behavior: A tourism example. Tourism Management, 31(6), 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y., & Mavondo, F. (2005). Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of travel risk perception. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y., & Mavondo, F. T. (2006). Cultural differences in travel risk perception. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 20(1), 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosselló, J., Becken, S., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2020). The effects of natural disasters on international tourism: A global analysis. Tourism Management, 79, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, P. M., & Siguaw, J. A. (2008). Perceived travel risks: The traveller perspective and manageability. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., Sibi, P., Yostb, E., & Singhb, D. (2021). Tourism and disability: A bibliometric review. Tourism Recreation Research, 48(2), 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S. F., & Graefe, A. R. (1998). Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. Journal of Travel Research, 37(2), 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, M. (2017). Are mendeley reader counts high enough for research evaluations when articles are published? Aslib Journal of Information Management, 69(2), 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- tom Dieck, M. C., & Jung, T. (2018). A theoretical model of mobile augmented reality acceptance in urban heritage tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(2), 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2022). Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Utkarsh, & Sigala, M. (2021). A bibliometric review of research on COVID–19 and tourism: Reflections for moving forward. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 100912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülker, P., Ülker, M., & Karamustafa, K. (2023). Bibliometric analysis of bibliometric studies in the field of tourism and hospitality. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 6(2), 797–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasvári, T. (2015). Risk, risk perception, risk management—A review of the literature. Public Finance Quarterly, 1, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Veijola, S. (2009). Gender as work in the tourism industry. Tourist Studies, 9(2), 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcaino-Suárez, L. P., & Díaz-Carrión, I. A. (2019). Gender in tourism research: Perspectives from Latin America. Tourism Review, 74(5), 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., & Lopez, C. (2020). Does communicating safety matter? Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildgaard, L., Schneider, J. W., & Larsen, B. (2014). A review of the characteristics of 108 author-level bibliometric indicators. Scientometrics, 101, 125–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E. Y., & Vital, S. M. (2017). PlumX: A tool to showcase academic profile and distinction. Digital Library Perspectives, 33(4), 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H., Zhang, Y., & Duan, K. (2020). Evolutionary overview of urban expansion based on bibliometric analysis in Web of Science from 1990 to 2019. Habitat International, 95, 102100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E. C. L., Khoo-Lattimore, C., & Arcodia, C. (2017). A systematic literature review of risk and gender research in tourism. Tourism Management, 58, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E. C. L., Khoo-Lattimore, C., & Arcodia, C. (2018a). Constructing space and self through risk taking: A case of asian solo female travelers. Journal of Travel Research, 57(2), 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E. C. L., Khoo-Lattimore, C., & Arcodia, C. (2018b). Power and empowerment: How Asian solo female travellers perceive and negotiate risks. Tourism Management, 68, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E. C. L., Sharif, S. P., & Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2015). Tourists’ risk perception of risky destinations: The case of Sabah’s eastern coast. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 15(3), 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E. C. L., Yang, M. J. H., & Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2019). The meanings of solo travel for Asian women. Tourism Review, 74(5), 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E. C. L., & Nair, V. (2014). Tourism at risk: A review of risk and perceived risk in tourism. Asia-Pacific Journal of Innovation in Hospitality and Tourism (APJIHT), 3(2), 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).