Monitoring Revenue Management Practices in the Restaurant Industry—A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

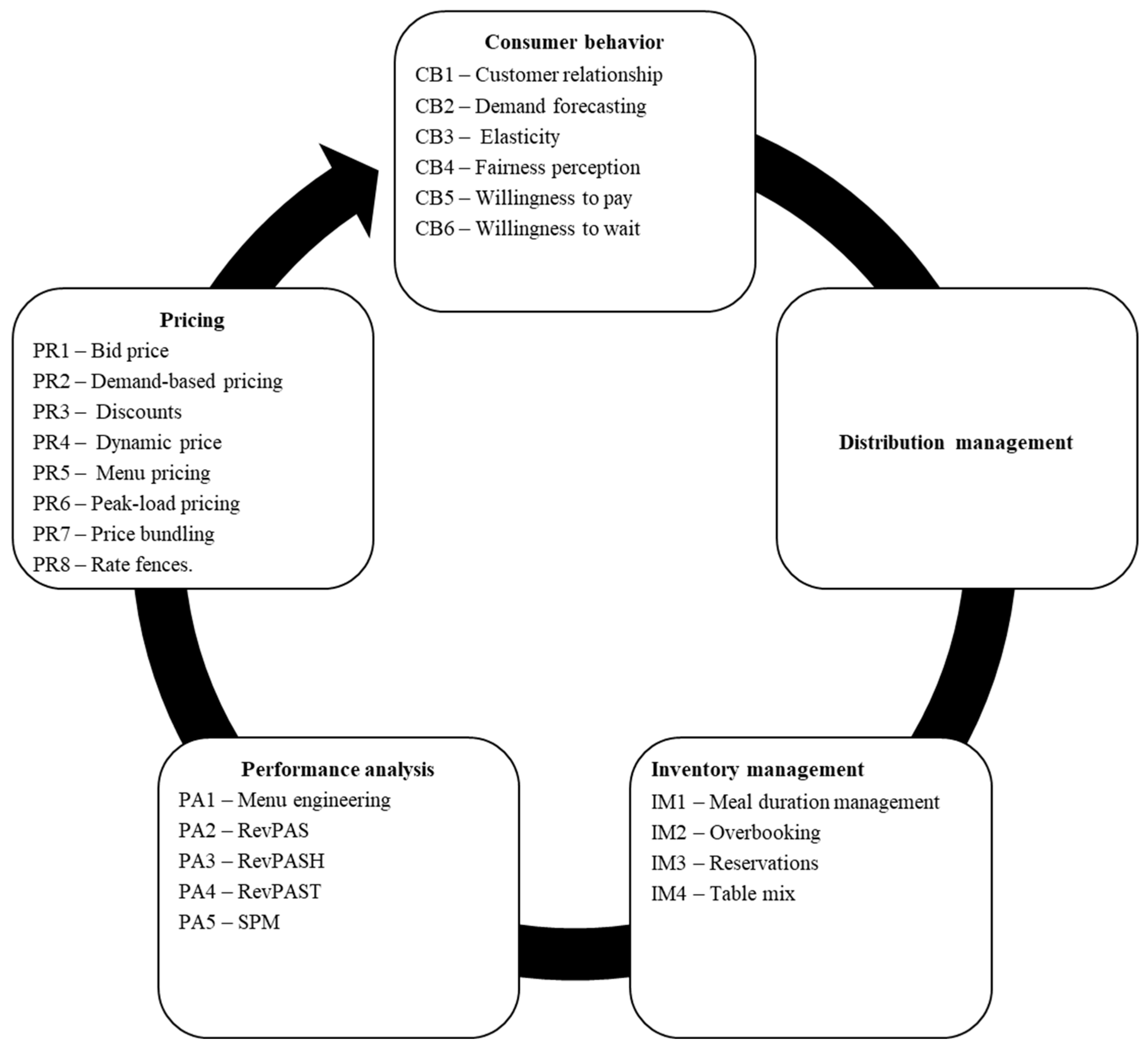

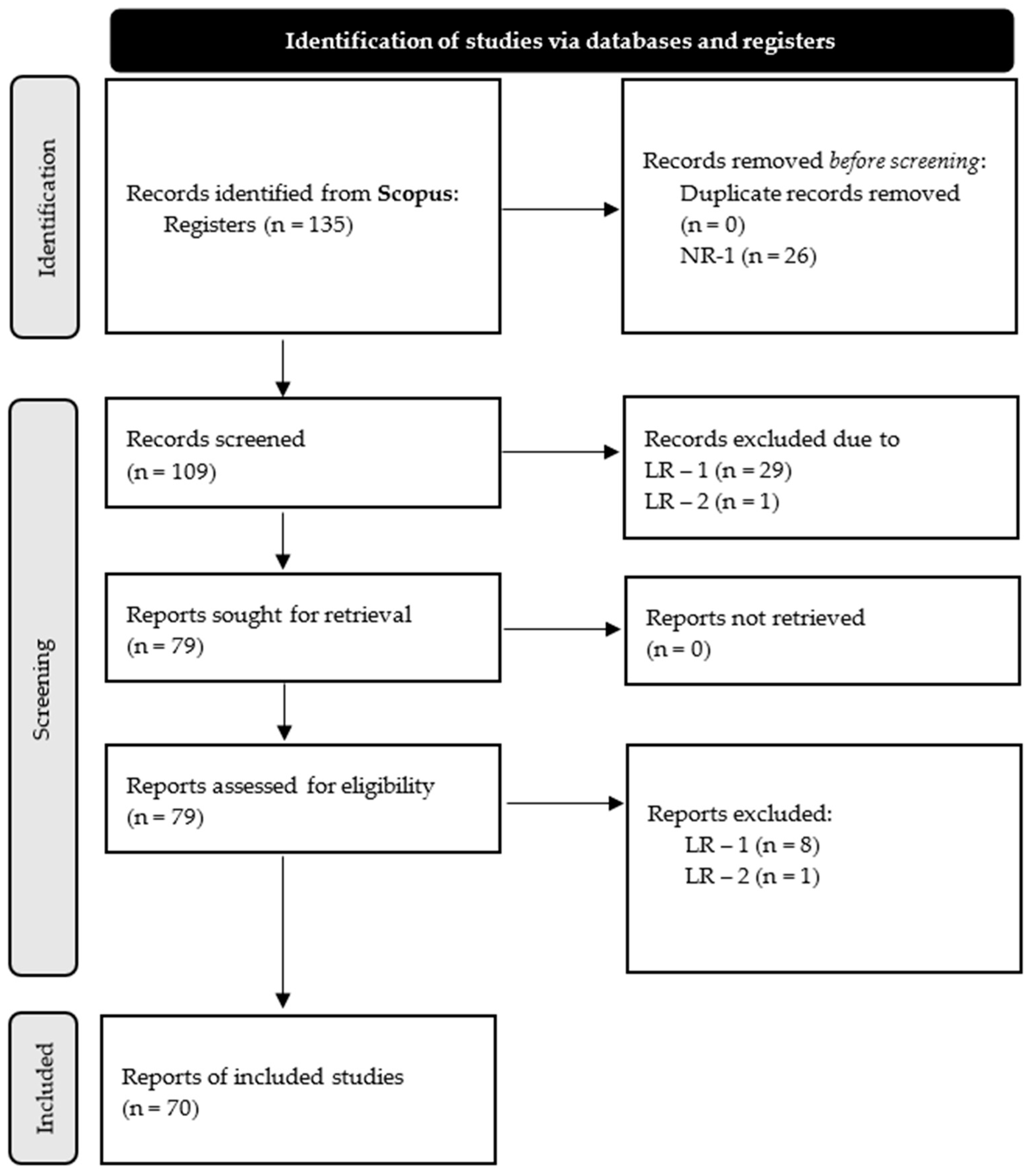

2. Materials and Methods

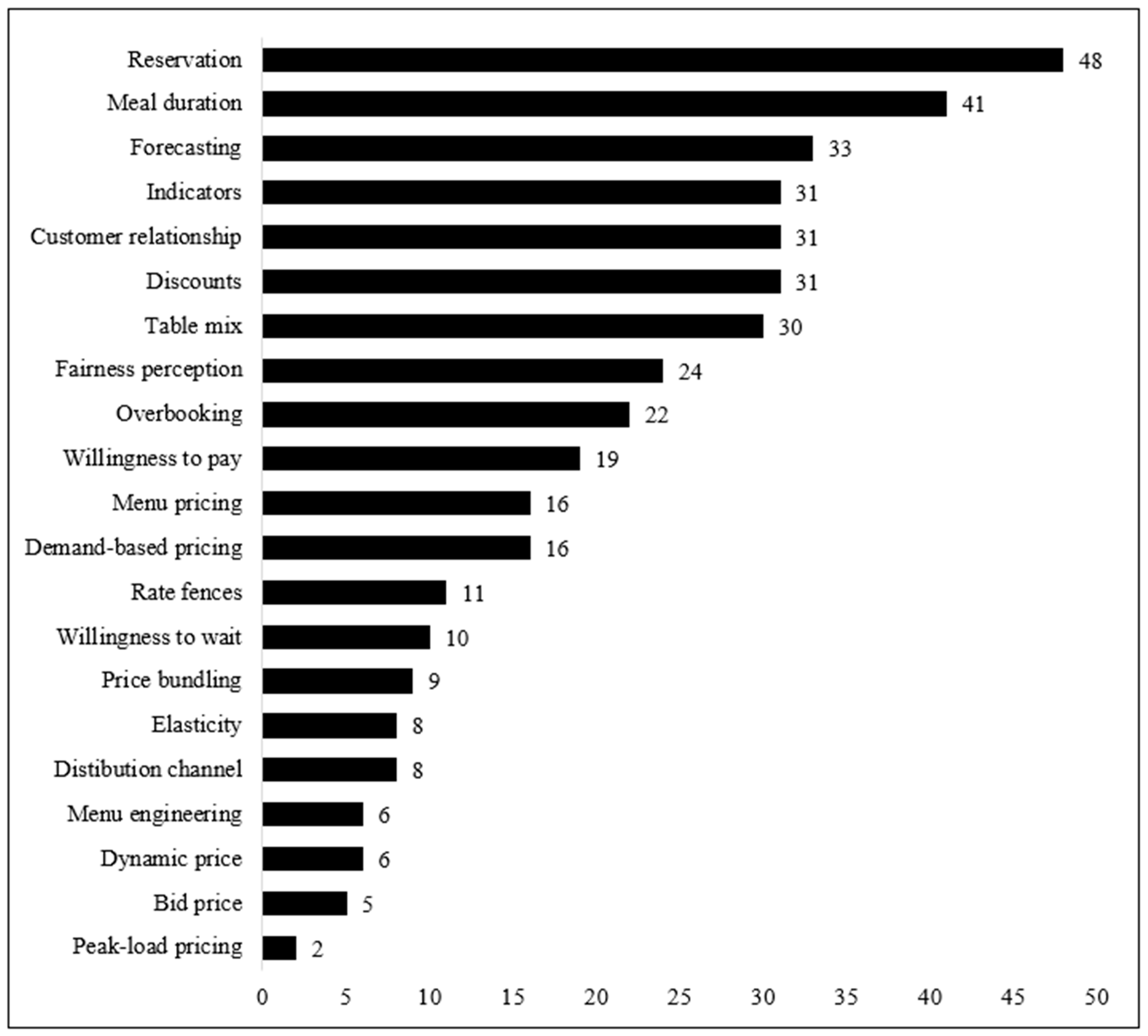

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Inventory Management

3.2. Customer Behavior

3.3. Pricing

3.4. Performance Analysis

3.5. Distribution Channels

3.6. The Challenges in Implementing and Adopting RM Practices in the Restaurant Industry

4. Conclusions

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sample of Studies

| Authors | Code Main Themes | Code Practices | Data Collection | Methods | Future Research |

| Webb et al. (2023) | PR | CB2; CB4; CB5 IM1; IM3 PA2; PA3; PA4; PA5 PR2; PR3; PR4; PR5; PR7; PR8 | Case study Primary source | Quantitative study | Searching during peak times, assessing the competition’s strength when evaluating the Priority Mixed Package, incorporating how the reservation is made, the speed, and the menu adaptation. |

| Belarmino and Repetti (2022) | CB | CB5 IM3 PR3; PR5; PR7 | Questionnaire survey and simulation | Quantitative study | Analyzing the distinction among restaurant types and investigating the willingness to pay by market segment. |

| Herrera and Young (2022) | CB; PA; PR | CB1; CB3; CB4; CB5 IM1; IM3 PA2 PR2; PR3; PR4; PR5; PR7 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Conducting the study in other countries, testing alternatives to Revenue Management implementation, and examining the impact of a restaurant on the local community and customer trust. |

| Tyagi and Bolia (2022) | PR; DC; IM; PA; CB | CB1; CB4 IM1; IM2; IM3; IM4 PA1; PA3 PR3 | Literature review | Qualitative study | Utilizing management software for various restaurants to assist with distribution channels; customer perception of fairness regarding RM strategies; and evaluation of discount strategies. |

| Kim et al. (2020) | CB; IM | CB1; CB3; CB4; CB5 IM1; IM4 PR2; PR3 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Investigating whether background music can have negative effects on customer wait times, utilizing psychological factors. |

| Collins et al. (2019) | PR | CB1; CB2 IM3 | Case study | Qualitative and quantitative study | Demonstrating that soft operational research methods can reduce the cognitive load of an analyst. |

| Lai et al. (2019) | PR | CB2 IM1; IM2; IM3 PR5 | Literature review | Qualitative study | More specific methods for analyzing a menu item; a holistic approach to restaurant profitability; and practical systems to assist in organizing restaurant data. |

| Legg et al. (2019) | CB; IM | CB2; CB6 IM1; IM3 PA3 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Non-parametric models. |

| Tang et al. (2019) | CB | CB1; CB2; CB4; CB5 IM1; IM2; IM3 PR2; PR3; PR4; PR5; PR8 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Specific restaurant revenue management policies, familiarity, demographics of customers with the intention to visit again, and the popularity of a restaurant. |

| Thompson (2019) | IM | CB2 IM1; IM3 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Extension of the flexibility of demand timing. |

| Etemad-Sajadi (2018) | CB; PR | CB2 PR2; PR3; PR8 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Long-term observation of consumer behaviors and perceptions over a 5 to 10-year period. |

| Denizci Guillet et al. (2018) | PR | CB4; CB5 IM1; IM3 PA3 PR2; PR3; PR5; PR8 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Table location pricing and sample expansion. |

| Mhlanga (2018) | PA | IM1 PA | Primary and secondary sources | Quantitative study | DEA’s technique is valuable for analyzing cost efficiency, as well as the factors that influence it in restaurants. |

| Miao et al. (2018) | IM | CB2 IM1; IM3; IM4 PR1 | Case study | Quantitative study | Addressing cancelations; combining adjacent tables; and general application of the proposed optimization method. |

| Ng et al. (2018) | DC; PR | CB1; CB5 DC IM1; IM3; IM4 PR3; PR8 | Restaurant distribution channels | Quantitative study | Extending the sampling time and incorporating data from other countries; exploring website popularity, web layouts, and the quantity of information provided. |

| Oh and Su (2018) | IM; PR | CB4; CB5 IM2; IM3 | Model | Quantitative study | Specifically investigating aspects related to price discrimination and reservation deposits. |

| Guo and Zheng (2017) | DC; PR | CB1; CB3 IM3 PR3 DC | Simulation | Quantitative study | The suggestion of a model with stochastic demand to provide more comprehensive management implications, realistically reflecting the changing behavior of loyal customers; application of an integrated model in a scenario of unobservable private information, using an asymmetric information game to address this issue. Additional information, such as geographic area and population density/restaurants, may be considered in the future. |

| Heo (2017) | PA | CB4 IM1; IM3; IM4 PA3; PROPASM | Literature review | Qualitative study | Applying indicators to empirical studies; discovering how optimal revenue management decisions for restaurants would differ using these new measures as opposed to RevPASH. |

| Song and Noone (2017) | CB; PA | CB1; CB4 IM1; IM2; IM4 PA4 PR3; PR8 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Examine the relative effects of various service encounter pacing methods on customer satisfaction and establish a consistent implementation method for on-site rhythm-related strategies. Apply this study to other countries. |

| Tse and Poon (2017) | IM | CB4; CB5 IM1; IM2; IM3 PR3; PR5 | Secondary sources | Quantitative study | To investigate the relationship between group size and no-show/cancelation rates; develop information technologies to assist managers in handling dynamic demand fluctuations and customers arriving at different times and staying for varying durations; examine customer sensitivity to prices without compromising revenue management; and explore the use of customer databases to personalize services. |

| Vieveen (2018) | CB | CB1; CB2; CB5 IM2; IM3; IM4 PA1 | Literature review | Qualitative study | Anticipating meal duration more accurately; increased application of overbooking; implementation of a loyalty program: a more personalized approach with customers. |

| J. F. Wang et al. (2017) | IM | CB2; CB5; CB6 IM1; IM3; IM4 PA3; PA5 PR3; PR5 | Discrete-event simulation models | Quantitative study | Make reservations according to the duration of the meal to increase RevPASH; implement SPM models; cut-off models to optimize revenue; harmonization of reservations and walk-ins to adjust arrival patterns and resource limitations. |

| Bacon et al. (2016) | PR | CB1; CB3; CB5 IM4 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Effects of location on pricing decisions; price elasticity could be measured by location, cuisine, and each individual restaurant attribute. |

| Gregorash (2016) | IM | CB1; CB5 IM3; IM4 PA3 PR5 | Secondary sources | Quantitative study | Customer interviews on motivations for making reservations; aligning marketing with revenue management; and differences in restaurant customer spending based on location and other specific demographic data, such as age, income, gender, and ethnicity. |

| Heo (2016) | DC | CB4 DC IM3; IM4; PR3; PR8 | Restaurant distribution channels | Quantitative study | Incorporating other countries to understand differences; introducing technology such as mobile applications to implement revenue management practices; expanding distribution channels and reservations through foreign websites; analyzing psychological factors influencing consumer behavior in the search for products on group shopping platforms. |

| Mathe-Soulek et al. (2016) | PR | CB1; CB2 PR3; PR5; PR7 | Secondary sources | Quantitative study | Examining how the introduction of new products impacts overall revenue changes, research and development costs, and restaurant profits; investigating perceptions of health benefits and product performance; analyzing promotions. |

| Zheng and Guo (2016) | DC; PR | CB1 DC IM3 PR3 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Stochastic market demand causing management implications in game-based analysis of information; optimal global solution for a restaurant. |

| Noone and Maier (2015) | DC; PA; PR | CB1; CB2; CB3 IM1; IM2; IM3; IM4 PA1; PA3 PR3; PR5 | Literature review | Qualitative study | The role of managers in customer perceptions of value and quality influencing choice behavior; upselling practices and positioning more likely to stimulate customer purchases; impact of revenue management practices on customer loyalty, satisfaction, and purchasing. |

| Thompson (2015a) | IM | CB2 IM3; IM4 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Investigate flexibility in arrival times; propose more comprehensive models; and integrate the stochastic nature of the problem. |

| Thompson (2015b) | IM | IM1; IM3; IM4 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Investigate offering a more limited menu; examine the effects of reducing demand or increasing prices during peak periods under conditions of higher excess demand. |

| Von Massow and McAdams (2015) | PR | PR7 | Case study Primary source | Quantitative study | Analysis of food residues in various commercial operations of food services; impact of different waste management strategies on customer experience and restaurant profit margins. |

| Bujisic et al. (2014) | CB; PR | CB2; CB4; CB5 IM2; IM3 PA3 PR4 | Interviews | Qualitative study | Entry fees and price sensitivity to develop appropriate pricing strategies; perception of fairness in revenue management principles and recommending strategies to optimize costs and prices without negatively impacting customer satisfaction or the environment; application of dynamic pricing (integration of specialized software). |

| Guerriero et al. (2014) | IM | IM1; IM3; IM4 PA3 PR1; PR4 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Verify that booking control policies perform better than the first come, first served. |

| Seo and Hwang (2014) | IM; PA | CB1; CB2 IM1 PA5 PR2; PR3 | Observation | Quantitative study | Long-term observation in various restaurants and across different countries; diverse factors such as age, relationship status, familiarity level, special occasions of customers, interactions with employees, service failures, and table characteristics should be studied in the future. |

| Heo et al. (2013) | IM; PR | CB1; CB2; CB4 IM1; IM3 PA3 PR2; PR3; PR5; PR6; PR7; PR8 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Exploration of the effects of perceived limited capacity in various contexts, identification of additional factors that may affect consumer evaluations of price information, analysis of cognitive processing as a mediator to understand the underlying mechanism of scarcity effects, and consideration of customer reactions in advantageous situations. |

| Kimes and Beard (2013) | PR | CB2; CB3; CB4 IM1; IM2; IM3; IM4 PA1; PR5 | Literature review | Qualitative study | Further studies on psychological principles of pricing; table mix; reservation systems that take into account demand, meal duration, customer value, and table allocation; menu design; promotion; and customers. |

| Bloom et al. (2012) | CB; IM | CB1; CB2 IM1 | Case study | Quantitative study | Conducting a study based on the efficiency of waitstaff in casual dining restaurants to predict meal duration, considering mealtime, group size, and waitstaff efficiency; assessing the impact of atmospheric factors on meal duration; and examining the influence of wine service on meal duration. |

| Noone et al. (2012) | CB | CB1 IM1 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Across diverse industries and various countries; testing other variables that influence the relationship between perceived pace and satisfaction. |

| Varini et al. (2012) | CB; PR | CB1; CB2; CB3; CB5 DC IM2; IM3 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Revenue management practices such as dynamic pricing; new tools and approaches to optimize revenue; maximizing the return on time and money; and utilization of new technologies. |

| Barth (2011) | IM; PA; PR | CB2 IM GERAL PA1; PA3 PR3; PR5 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Empirical tests. |

| Karmarkar and Dutta (2011) | CB; IM | CB2; CB4; CB6 IM1; IM2; IM3; IM4 PA3 PR1; PR2; PR3; PR4 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Varying service times and demands; combining tables to accommodate larger groups. |

| Kimes (2011b) | CB; IM | CB4 IM1; IM2 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Explore in depth the factors of perceived fairness, restaurant forecasting, best booking methods, and customer mix. |

| Kimes (2011a) | DC | CB1; CB2 DC IM3; IM4 | Restaurant distribution channels | Qualitative study | Identifying how revenue management and distribution methods implemented in other industries can be adapted to assist restaurants in effectively managing demand and devising new methods to address specific challenges. |

| Kwon and Jang (2011) | CB; PR | CB1; CB4 PR3; PR7 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Expand the sample size; investigate the impact of consumer attitudes towards a specific brand on the effects of price bundling; extend to other restaurant categories. |

| Thompson (2011a) | PA | CB6 IM1; IM3; IM4 PA3 PR5 | Questionnaire survey and simulation | Quantitative study | Extended exploration of the impact of cherry-picking on customer satisfaction, analysis of the ethical implications of cherry-picking, and investigation of the effectiveness of different cherry-picking strategies. |

| Thompson (2011b) | IM | CB1; CB6 IM3; IM4 PA3 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Impact of rounding rules on naïve methods and evaluation of using the best among the four naïve table combinations as a starting point for a Simulated Annealing-based heuristic. |

| Kizildag et al. (2010) | PR | CB2 PR3; PR7 | Secondary sources | Quantitative study | Application of Revenue Management (RM) concepts in table management, in-depth analysis of evaluation models used in table management; growth strategies for risk management, investment, and value creation in the strategy. |

| Thompson (2010) | CB | CB2 | Literature review | Qualitative study | Factors affecting restaurant profitability; customer demand forecasting through methods and metrics; customer expenses; impact on profitability, and exploration of decision-making processes. |

| Hwang and Yoon (2009) | CB | CB1; CB4; CB5 IM4 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Interior features such as atmosphere, environment, lighting, seating comfort, restaurant size and layout, restaurant service and other arrangements, seating configurations, and the impacts of social factors can be studied in the future. |

| Noone and Mattila (2009) | CB | CB1; CB5 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Research is needed in other services to generalize the results. |

| Thompson (2009) | CB; IM | CB4; CB6 IM1; IM3; IM4 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Create a simulation model that captures the nuances and interdependencies in a real system |

| Thompson and Sohn (2009) | IM; PA | IM1; IM3; IM4 PA3 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Empower academic researchers to ensure that their results are not tainted by inaccuracies in RevPASH calculations. |

| Chan and Chan (2008) | IM | CB2; CB6 IM1; IM2; IM3; IM4 PA3 PR2; PR8 | Interviews | Qualitative study | In-depth research on entry fees and price sensitivity to develop appropriate pricing strategies; recommending strategies to optimize costs and prices without negatively impacting customer satisfaction or the environment in these establishments; implementation of dynamic pricing in beverage establishments (integration of specialized software). |

| Kimes (2008) | CB | CB2 DC IM1; IM2; IM3; IM4 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Balancing the costs associated with technology adoption with potential benefits; carefully assessing the effects on customer and employee satisfaction; considering the revenue potential associated with proper technology adoption. |

| Heide et al. (2008) | CB; PR | CB1; CB5 IM3 PR2; PR3; PR6; PR7 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | The study of corporate customers should be considered in future research to analyze the design of pricing strategies that meet the demands of this group. |

| Palmer and McMahon-Beattie (2008) | PR | CB1; CB2; CB4 PR3 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | To study a set of diverse environmental characteristics and correlate them with customer trust. |

| Thompson and Kwortnik (2008) | IM | CB1; CB2 IM1; IM2; IM3; IM4 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Study of overbooking and no-shows; application of various sampling techniques and result robustness; examination of different control factors influencing the relationship between perceived pace and customer satisfaction; investigation of meal duration reduction. |

| Noone et al. (2007) | CB; IM | CB1; CB2 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Generalization of results; different types of restaurants; influence of the relationship between perceived pace and customer satisfaction. |

| McGuire and Kimes (2006) | CB | CB1; CB4; CB6 IM3 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | Understand what customers consider to be the reference transaction in restaurant waiting situations; better understand the difference between reference transaction violations that have financial implications and those that do not. |

| Kimes and Thompson (2005) | IM | IM1; IM2; IM4 PA2 PR1; PR2; PR3 | Simulation | Quantitative study | In-depth exploration of capacity management; enhancement of NaïveIP models by incorporating factors such as demand intensity and variations in customer values based on group size; assessment of the impact of different table assignment rules; expansion of the investigation to other sectors. |

| Kimes (2004) | PA | CB2 IM1; IM2; IM3; IM4 PA3 PR2; PR3 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Verify similar results in other studies. |

| Kimes and Robson (2004) | IM; PA | CB1 IM1; IM4 PA3 | Case study Primary source | Quantitative study | Maximizing revenue through a different SPM; opportunities to fine-tune restaurant operations |

| Kimes and Thompson (2004) | IM | CB1 IM1; IM2; IM3; IM4 PA3 | Simulation | Quantitative study | The development of the optimal blend in other industries may be considered in the future, as well as the effects of prediction errors and table-combining policies. |

| Susskind et al. (2004) | CB; PR | CB3; CB4 IM1; IM3 PR2; PR3; PR8 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | The connection between customer demands and the restaurant’s unique capacity to meet those demands, as well as service plans and the optimization of employee productivity, is regarded as a subject for future investigation. |

| Bertsimas and Shioda (2003) | CB | CB2; CB4; CB6 IM1; IM2; IM3 PA3 PR1; PR2 | Simulation model | Quantitative study | Expanding the model to support dynamic capacity and enable table mobility; incorporating dropout and waiver; conducting additional empirical tests. |

| Kimes and Wirtz (2003) | CB; DC; PR | CB2; CB4; CB5 DC IM2; IM3 PR3; PR5; PR8 | Questionnaire survey | Quantitative study | It should address the perception of fairness in pricing practices and revenue management duration across other sectors. Additionally, it should investigate how these revenue management practices are perceived in different countries. |

| Kimes (1999) | CB | IM1 PA3 PR3 | Simulation | Quantitative study | Establishing a reference framework, including the types of data to be collected, potential data sources, and the analysis and interpretation of gathered information; integrating revenue management information to enhance RevPASH. |

| Kimes et al. (1999) | CB | IM1; IM3 PA3 | Literature review | Qualitative study | Implementation of RM strategies, emphasizing the impact of these approaches on RevPASH and financial performance, along with the deployment of training and incentive programs for managers and employees. |

| Kimes et al. (1998) | PR | IM1; IM2; IM3 PA1; PA3 PR2; PR3 | Literature review | Qualitative study | Utilization of a framework to assist restaurant managers in identifying revenue management opportunities and developing appropriate strategies for managing duration and implementing differentiated pricing approaches. |

| Cross (1997) | PR | CB2; CB6 IM3 | Literature review | Qualitative study | Before going ahead with RM, think very carefully about all the elements that make up the RM of the company- |

| Notes: CB—consumer behavior; CB1—customer relationship; CB2—demand forecasting; CB3—elasticity; CB4—fairness perception; CB5—willingness to pay; CB6—willingness to wait; DCs—distribution channels; IM—inventory management; IM1—meal duration management; IM2—overbooking; IM3—reservations; IM4—table mix; PA—performance analysis; PA1—menu engineering; PA2—RevPAS; PA3—RevPASH; PA4—RevPAST; PA5—SPM; PR—pricing—PR1—bid price; PR2—demand-based pricing; PR3—discounts; PR4—dynamic price; PR5—menu pricing; PR6—peak load pricing; PR7—price bundling; PR8—rate fences. | |||||

References

- Abrate, G., Nicolau, J. L., & Viglia, G. (2019). The impact of dynamic price variability on revenue maximization. Tourism Management, 74, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampountolas, A., Baltazar, M., Beck, J., Belarmino, A., Berezina, K., Denizci Guillet, B., Kim, M., Kim, W., Lee, M., Ling, L., Mauri, A., Parsa, H. G., Repetti, T., Schwartz, Z., Smith, S., Stringam, B., Tang, C., Rest, J., & Webb, T. (2021). Hospitality revenue management & profit optimization (1st ed.). Toni Repetti. [Google Scholar]

- Asyraff, M., Hanafiah, M., Aminuddin, N., & Mahdzar, M. (2023). Adoption of the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) model in hospitality and tourism research: Systematic literature review and future research directions. Asia-Pacific Journal of Innovation in Hospitality and Tourism, 12(1), 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, D. R., Besharat, A., Parsa, H. G., & Smith, S. J. (2016). Revenue management, hedonic pricing models and the effects of operational attributes. International Journal of Revenue Management, 9(2/3), 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, J. E. J. (2011). A model for the wine list and wine inventory yield management. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarmino, A., & Repetti, T. (2022). How restaurants’ adherence to COVID-19 regulations impact consumers’ willingness-to-pay. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 27, 667–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsimas, D., & Shioda, R. (2003). Restaurant revenue management. Operations Research, 51(3), 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binesh, F., Belarmino, A., & Raab, C. (2021). A meta-analysis of hotel revenue management. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 20, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B. A. N., Hummel, E. E., Aiello, T. H., & Li, X. (2012). The impact of meal duration on a corporate casual full-service restaurant chain. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 15(1), 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujisic, M., Hutchinson, J., & Bilgihan, A. (2014). The application of revenue management in beverage operations. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 17(4), 336–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büsing, C., Kadatz, D., & Cleophas, C. (2019). Capacity uncertainty in airline revenue management: Models, algorithms, and computations. Transportation Science, 53(2), 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F., Gomes, C., Cardoso, L., & Lima Santos, L. (2022a). Management accounting practices in the hospitality industry: The portuguese background. International Journal of Financial Studies, 10(4), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F., Lima Santos, L., Gomes, C., & Cardoso, L. (2022b). Management accounting practices in the hospitality industry: A systematic review and critical approach. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(1), 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L., Araújo, A. F., Lima Santos, L., Schegg, R., Breda, Z., & Costa, C. (2021). Country performance analysis of Swiss tourism, leisure and hospitality management research. Sustainability, 13, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W. W., & Chan, L. C. (2008). Revenue management strategies under the lunar-solar calendar: Evidence of Chinese restaurant operations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(3), 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesterton, L., Stephens, M., Clark, A., & Ahmed, A. (2021). A systematic literature review of the patient hotel model. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(3), 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A., Shull, J., & Thaviphoke, Y. (2019). The need for simple educational case-studies to show the benefit of soft operations research to real-world problems. International Journal of System of Systems Engineering, 9(1), 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, R. (1997). Lauching the revenue rocket: How revenue management can work for your business. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 38(2), 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakıroğlu, A. D., Önder, L. G., & Eren, B. A. (2020). Relationships between brand experience, customer satisfaction, brand love and brand loyalty: Airline flight service application. Gümüşhane Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Elektronik Dergisi, 11(3), 888–898. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/gumus/issue/57505/699167 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Denizci Guillet, B., Law, R., & Kucukusta, D. (2018). How do restaurant customers make trade-offs among rate fences? Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 21(4), 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denizci Guillet, B., & Mohammed, I. (2015). Revenue management research in hospitality and tourism: A critical review of current literature and suggestions for future research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(4), 526–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, R. (2017). Restaurant and foodservice research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(4), 1203–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, H., & Donato, M. (2019). Stages for undertaking a systematic review. In Acta medica portuguesa (Vol. 32, Issue 3, pp. 227–235). CELOM. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad-Sajadi, R. (2018). Are customers ready to accept revenue management practices in the restaurant industry? International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, 35(4), 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T., Vukolić, D., Zrnić, M., & Dénes, D. L. (2023). The quality of hotel service as a factor of achieving loyalty among visitors. Hotel and Tourism Management, 11(1), 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C., Malheiros, C., Campos, F., & Lima Santos, L. (2022). COVID-19’s impact on the restaurant industry. Sustainability, 14(18), 11544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorash, B. J. (2016). Restaurant revenue management: Apply reservation management? Information Technology and Tourism, 16(4), 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, F., Miglionico, G., & Olivito, F. (2014). Strategic and operational decisions in restaurant revenue management. European Journal of Operational Research, 237, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., & Zheng, X. (2017). Examination of restaurants online pricing strategies: A game analytical approach. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 26(6), 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, M., White, C., Grønhaug, K., & Østrem, T. M. (2008). Pricing strategies in the restaurant industry. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 8(3), 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, C. Y. (2016). Exploring group-buying platforms for restaurant revenue management. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 52, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, C. Y. (2017). New performance indicators for restaurant revenue management: ProPASH and ProPASM. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, C. Y., Lee, S., Mattila, A., & Hu, C. (2013). Restaurant revenue management: Do perceived capacity scarcity and price differences matter? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, C., & Young, C. A. (2022). Revenue management in restaurants: The role of customers’ suspicion of price increases. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 26, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Franco, G., Montalván-Burbano, N., Carrión-Mero, P., Apolo-Masache, B., & Jaya-Montalvo, M. (2020). Research trends in geotourism: A bibliometric analysis using the scopus database. Geosciences, 10(10), 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebl, M. (2021). Sample selection in systematic literature reviews of management research. Organizational Research Methods, 26(2), 229–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J., & Yoon, S. Y. (2009). Where would you like to sit? Understanding customers’ privacy-seeking tendencies and seating behaviors to create effective restaurant environments. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 12(3), 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infantes-Paniagua, Á., Silva, A. F., Ramirez-Campillo, R., Sarmento, H., González-Fernández, F. T., González-Víllora, S., & Clemente, F. M. (2021). Active school breaks and students’ attention: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Brain Sciences, 11(6), 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S. (2014). Hotel revenue management—From theory to practice (1st ed.). Zangador, Ltd. ISBN 978-954-92786-3-7. [Google Scholar]

- Janowski, A., & Martynyuk, V. (2023). Defining talent in management science: Does it really matter? Argumenta Oeconomica, 2(51), 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S., Lee, G., & Moon, I. (2024). Airline dynamic pricing with patient customers using deep exploration-based reinforcement learning. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 133((Pt A)), 108073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmarkar, S., & Dutta, G. (2011). Optimal table-mix and acceptance-rejection problems in restaurants. International Journal of Revenue Management, 5(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H., Song, H., & Youn, H. (2020). The chain of effects from authenticity cues to purchase intention: The role of emotions and restaurant image. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 85, 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S. (1989). The basics of yield management. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 30(3), 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S. (1999). Implementing restaurant revenue management: A five-step Approach. Quarterly Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration, 40, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S. (2004). Restaurant revenue management: Implementation at chevys arrowhead. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 45(1), 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S. (2005). Restaurant revenue management: Could it work? Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 4, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S. (2008). The Role of Technology in Restaurant Revenue Management. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 49(3), 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S. (2011a). The future of distribution management in the restaurant industry. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 10(2), 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S. (2011b). Customer attitudes towards restaurant reservations policies. Journal of Revenue and Pricing, 10(3), 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S., Barrash, D. I., & Alexander, J. E. (1999). Developing a Restaurant Revenue-management Strategy. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 40(5), 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S., & Beard, J. (2013). The future of restaurant revenue management. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 12, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S., Chase, R. B., Choi, S., Lee, P. Y., & Ngonzi, E. N. (1998). Restaurant revenue management: Applying yield management to the restaurant industry. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 39(3), 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S., & Robson, S. (2004). The impact of restaurant table characteristics on meal duration and spending. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 45(4), 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S., & Thompson, G. M. (2004). Restaurant Revenue Management at Chevys: Determining the Best Table Mix. Decision Sciences, 35(3), 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S., & Thompson, G. M. (2005). An evaluation of heuristic methods for determining the best table mix in full-service restaurants. Journal of Operations Management, 23, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S., & Wirtz, J. (2003). Has revenue management become acceptable? Findings from an international study on the perceived fairness of rate fences. Journal of Service Research, 6(2), 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizildag, M., Barber, N., & Goh, B. K. (2010). Managing investment revenue. International Journal of Revenue Management, 4(2), 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, N., Alves, M. C., & Martins, I. (2021). The impacts of emerging technologies on accountants’ role and skills: Connecting to open innovation—A systematic literature review. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S., & Jang, S. (2011). Price bundling presentation and consumer’s bundle choice: The role of quality certainty. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(2), 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H. B. J., Karim, S., Krauss, S. E., & Ishak, F. A. (2019). Can restaurant revenue management work with menu analysis? Journal of Revenue Pricing Management, 18, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, M., Tang, H., Chun, H., Hancer, M., & Slevitch, L. (2019). Using survival modeling for turn-time predictions in foodservice settings. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 22(1), 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legohérel, P., Potier, E., & Fyall, A. (2013). Revenue management for hospitality and tourism. Goodfellow Publishers Limited. ISBN 978-1-908999-50-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lima Santos, L., Gomes, C., Faria, A., Lunkes, R., Malheiros, C., Silva da Rosa, F., & Nunes, C. (2016). Contabilidade de gestão hoteleira (1st ed.). ATF Edições Técnicas. ISBN 9789899894433. [Google Scholar]

- Lima Santos, L., Silva, R., Cardoso, L., & Oliveira, C. (2022). Accounting and business management research: Tracking 50 years of country performance. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 26(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Londono-Giraldo, B., López Ramirez, Y. M., & Vargas-Piedrahita, J. (2024). Engagement and loyalty in mobile applications for restaurant home deliveries. Heliyon, 10(7), e28289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M., & Costa, R. (2017). Backpackers’ contribution to development and poverty alleviation: Myth or reality? A critical review of the literature and directions for future research. European Journal of Tourism Research, 16, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathe-Soulek, K., Krawczyk, M., Harrington, R. J., & Ottenbacher, M. (2016). The impact of price-based and new product Promotions on fast food restaurant sales and stock prices. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 22(1), 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, T. (2020). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, K. A., & Kimes, S. (2006). The perceived fairness of waitlist-management techniques for restaurants. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 47(2), 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, O. (2018). Factors impacting restaurant efficiency: A data envelopment analysis. Tourism Review, 73(1), 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q., Li, Y., & Wang, X. B. (2018). Restaurant reservation management considering table combination. Pesquisa Operacional, 38(1), 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaalian, F., & Halpenny, E. (2019). Social media analytics in hospitality and tourism: A systematic literature review and future trends. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 10(4), 764–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, F. (2002). Food and beverage management handbook (1st ed.). CETOP. ISBN 9789726415213. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, C. (2020). Restaurant organizations and the power of the new economy: A pandemic, labor value and lessons from the past. School of Hospitality Administration. Available online: https://www.bu.edu/bhr/2020/03/19/restaurant-organizations-and-the-power-of-the-new-economy-a-pandemic-labor-value-and-lessons-from-the-past/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Ng, F., Cui, C., & Harrison, J. (2018). Minding your Ts and Cs: How do rate fences affect restaurant deal promotion outcomes? Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 17(3), 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, B. M., Kimes, S. E., Mattila, A. S., & Wirtz, J. (2007). The effect of meal pace on customer satisfaction. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 48(3), 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, B. M., & Maier, T. (2015). A decision framework for restaurant revenue management. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 14, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, B. M., & Mattila, A. S. (2009). Consumer reaction to crowding for extended service encounters. Managing Service Quality, 19(1), 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, B. M., Wirtz, J., & Kimes, S. E. (2012). The effect of perceived control on consumer responses to service encounter pace: A revenue management perspective. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 53(4), 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRA. (2022). Restaurant employee demographics. Available online: https://restaurant.org/getmedia/6f8b55ed-5b3f-40f5-ad04-709ff7ff9f0f/nra-data-brief-restaurant-employee-demographics.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Ogutu, H., El Archi, Y., & Dénes Dávid, L. (2023). Current trends in sustainable organization management: A bibliometric analysis. Oeconomia Copernicana, 14(1), 11–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J., & Su, X. (2018). Reservation policies in queues: Advance deposits, spot prices, and capacity allocation. Production and Operations Management, 27(4), 680–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A., & McMahon-Beattie, U. (2008). Variable pricing through revenue management: A critical evaluation of affective outcomes. Management Research News, 31(3), 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., & Criado, A. R. (2020). The art of writing a literature review: What do we Know and what do we need to Know? International Business Review, 29(4), 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., Khatri, P., & Duggal, H. (2023). Frameworks for developing impactful systematic literature reviews and theory building: What, why and how? Journal of Decision Systems, 33, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D., Spiliotopoulou, E., & Vries, J. (2022). Restaurant analytics: Emerging practice and research opportunities. Production and Operations Management, 31(10), 3687–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopus. (2023). Scopus-journal of innovation and knowledge. Elsevier. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/sourceid/21100932830?origin=resultslist (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Seo, S., & Hwang, J. (2014). Does gender matter? Examining gender composition’s relationships with meal duration and spending in restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 42, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, A., Shah, B. J., & Gajjar, H. (2022). Online food delivery research: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(8), 2852–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M., & Noone, B. M. (2017). The moderating effect of perceived spatial crowding on the relationship between perceived service encounter pace and customer satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 65, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, A. M., Reynolds, D., & Tsuchiya, E. (2004). An evaluation of guests’ preferred incentives to shift time-variable demand in restaurants. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 45(1), 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J., Repetti, T., & Raab, C. (2019). Perceived fairness of revenue management practices in casual and fine-dining restaurants. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 2(1), 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G. M. (2009). (Mythical) Revenue benefits of reducing dining duration in restaurants. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 50(1), 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G. M. (2010). Restaurant profitability management: The evolution of restaurant revenue management. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 51(3), 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G. M. (2011a). Cherry-Picking customers by party size in restaurants. Journal of Service Research, 14(2), 201–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G. M. (2011b). Inaccuracy of the “Naïve Table Mix” Calculations. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 52(3), 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G. M. (2015a). An evaluation of integer programming models for restaurant reservations. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 14(5), 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G. M. (2015b). Deciding Whether to offer “Early-Bird” or “Night-Owl” specials in restaurants: A cross-functional view. Journal of Service Research, 18(4), 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G. M. (2019). The value of timing flexibility in restaurant reservations. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 60(4), 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G. M., & Kwortnik, R. J. (2008). Pooling restaurant reservations to increase service efficiency. Journal of Service Research, 10(4), 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G. M., & Sohn, H. (2009). Time-and capacity-based measurement of restaurant revenue. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 50(4), 520–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge using systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, T. S. M., & Poon, Y. T. (2017). Modeling no-shows, cancellations, overbooking, and walk-ins in restaurant revenue management. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 20(2), 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, M., & Bolia, N. B. (2022). Approaches for restaurant revenue management. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 21(1), 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varini, K., Sirsi, P., & Kamensky, S. (2012). Revenue management and India: Rapid deployment strategies. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 4(5), 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, R., Flores, L., Almagro, R., Amora, M., & Lopez, J. (2023). The best practices of financial management in education: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, VII(VIII), 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieveen, I. (2018). Lost opportunities in restaurant revenue management. Journal of Revenue Pricing Management, 17, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Massow, M., & McAdams, B. (2015). Table scraps: An evaluation of plate waste in restaurants. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 18(5), 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. F., Lin, Y. C., Kuo, C. F., & Weng, S. J. (2017). Cherry-picking restaurant reservation customers. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Heo, C., Schwartz, Z., Legohérel, P., & Specklin, F. (2015). Revenue management: Progress, challenges, and research prospects. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 32(7), 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T., Ma, J., & Cheng, A. (2023). Variable pricing in restaurant revenue management: A priority mixed bundle strategy. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 64(1), 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., & Watson, M. (2019). Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(1), 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Hu, L., Guo, X., & Yan, X. (2020). Online cooperation mechanism: Game analysis between a restaurant and a third-party website. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 19, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yembergenov, R., & Zharylkasinova, M. (2019). Management accounting in the restaurant business: Organization methodology. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 7(2), 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X., & Guo, X. (2016). E-retailing of restaurant services: Pricing strategies in a competing online environment. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 67(11), 1408–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I., & Čater, T. (2014). Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organizational Research Methods, 18(3), 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Restaurant RM Practices | Restaurant Application | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| IM1 | Meal duration management |

|

|

| IM2 | Overbooking |

|

|

| IM3 | Reservations |

|

|

| IM4 | Table mix |

|

|

| CB1 | Customer relationship |

|

|

| CB2 | Demand forecasting |

|

|

| CB3 | Elasticity |

|

|

| CB4 | Fairness perception |

|

|

| CB5 | Willingness to pay |

|

|

| CB6 | Willingness to wait |

|

|

| PR1 | Bid price |

|

|

| PR2 | Demand-based pricing |

|

|

| PR3 | Discounts |

|

|

| PR4 | Dynamic price |

|

|

| PR5 | Menu pricing |

|

|

| PR6 | Peak-load pricing |

|

|

| PR7 | Price bundling |

|

|

| PR8 | Rate fences |

|

|

| PA1 | Menu engineering |

|

|

| PA2 PA3 PA4 PA5 | Indicators |

|

|

| DC | Distribution channel |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malheiros, C.; Gomes, C.; Lima Santos, L.; Campos, F. Monitoring Revenue Management Practices in the Restaurant Industry—A Systematic Literature Review. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010044

Malheiros C, Gomes C, Lima Santos L, Campos F. Monitoring Revenue Management Practices in the Restaurant Industry—A Systematic Literature Review. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalheiros, Cátia, Conceição Gomes, Luís Lima Santos, and Filipa Campos. 2025. "Monitoring Revenue Management Practices in the Restaurant Industry—A Systematic Literature Review" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010044

APA StyleMalheiros, C., Gomes, C., Lima Santos, L., & Campos, F. (2025). Monitoring Revenue Management Practices in the Restaurant Industry—A Systematic Literature Review. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6010044