Rare Presentation, Critical Diagnosis: Primary Actinomycosis of the Foot

Abstract

1. Introduction

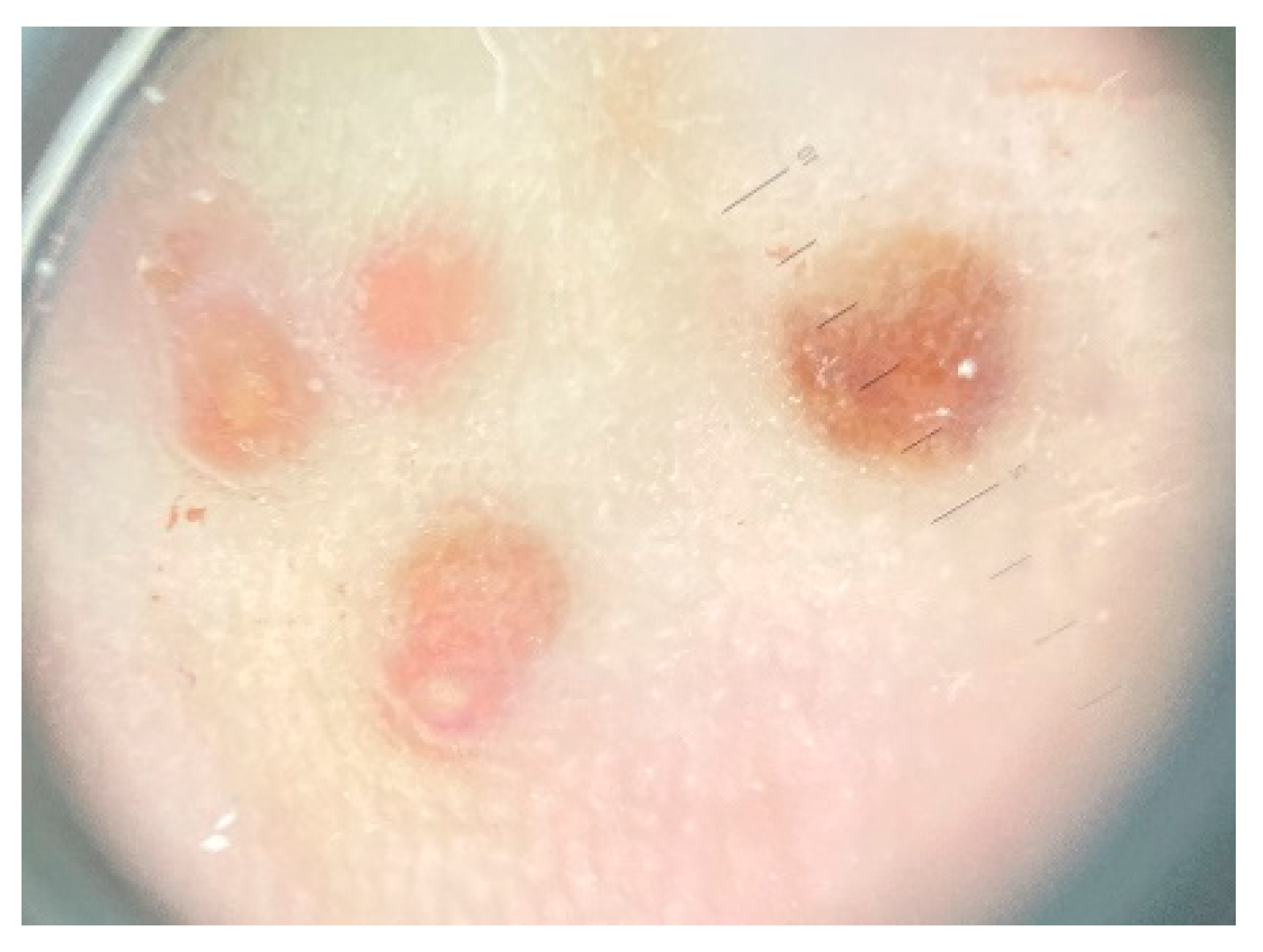

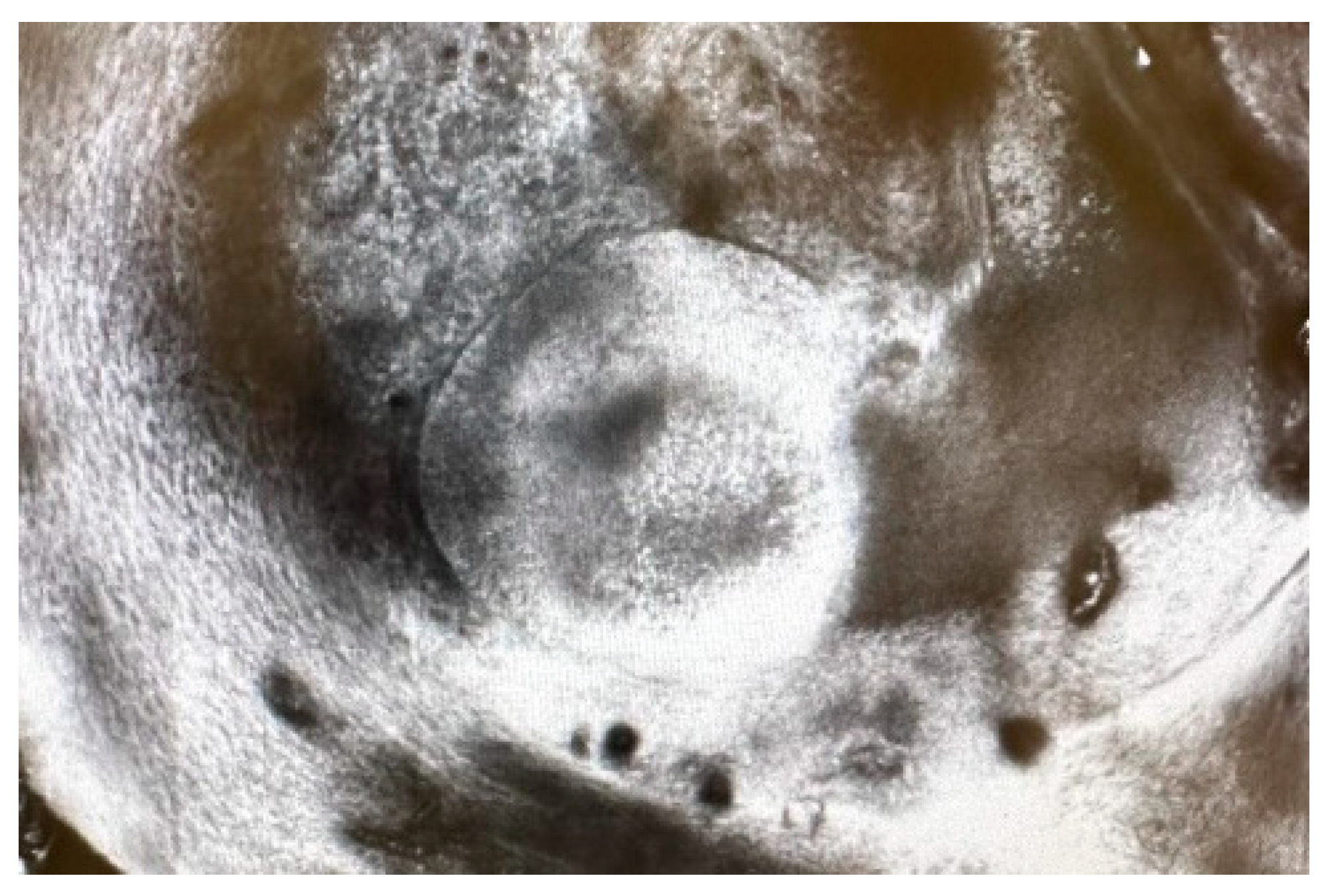

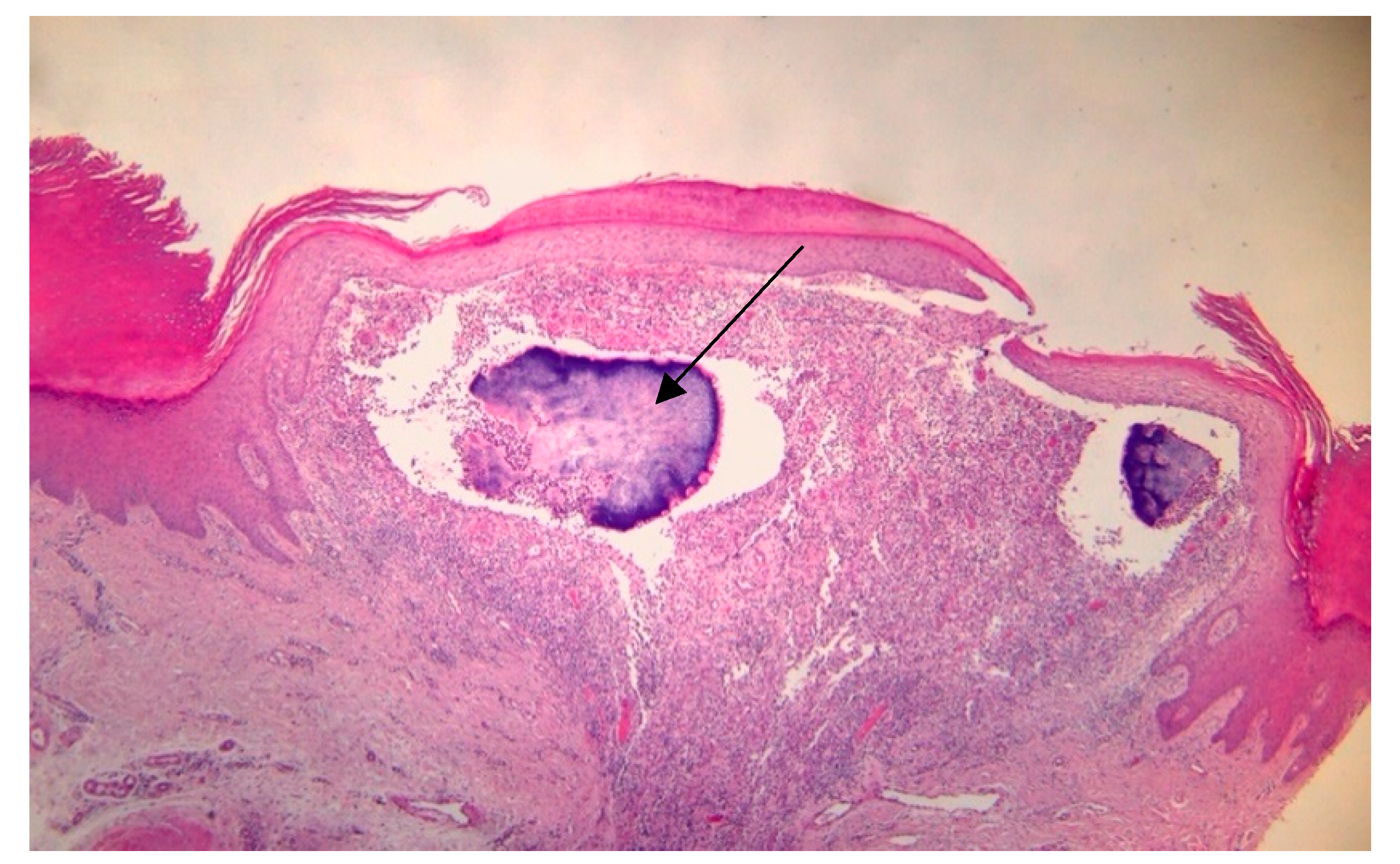

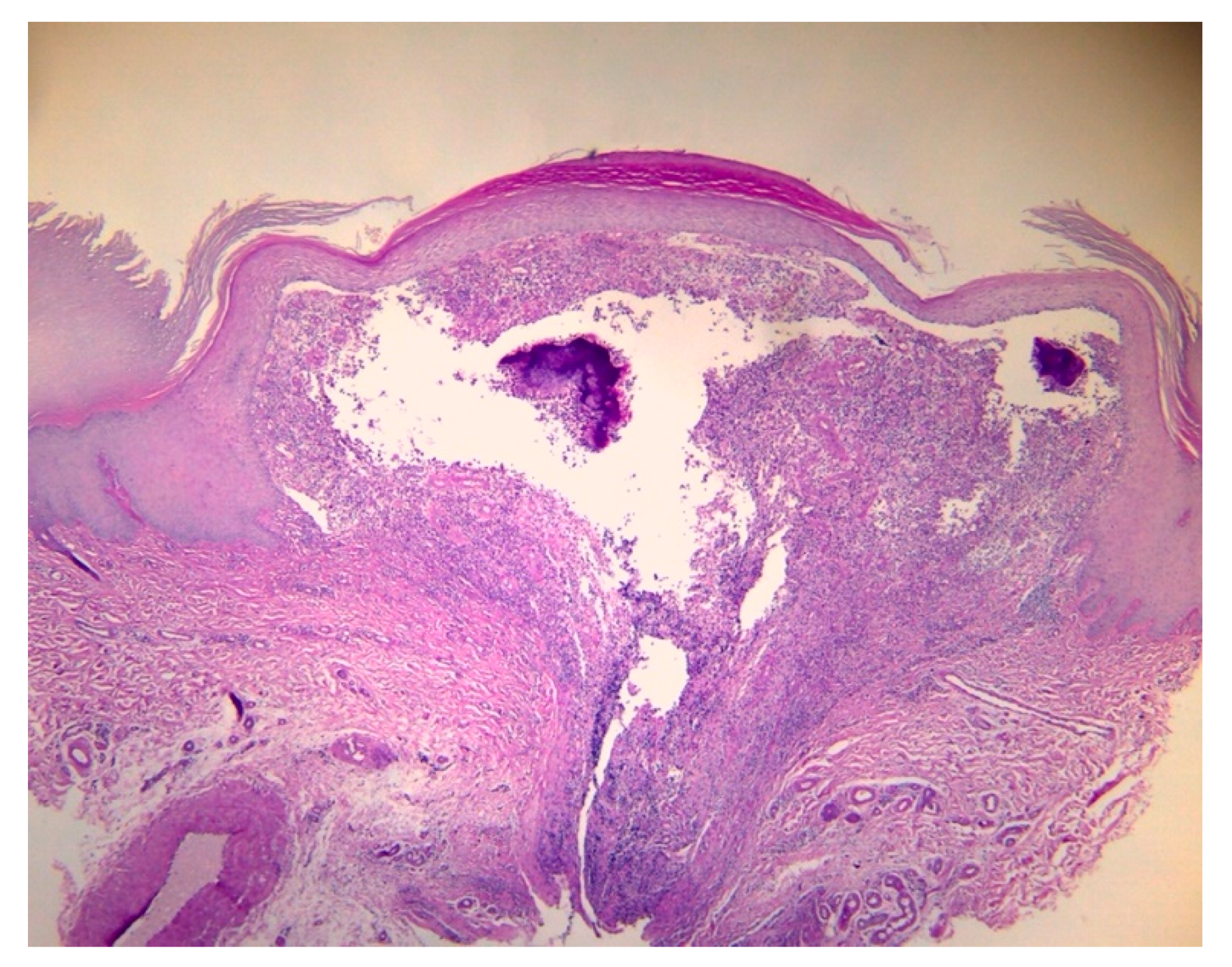

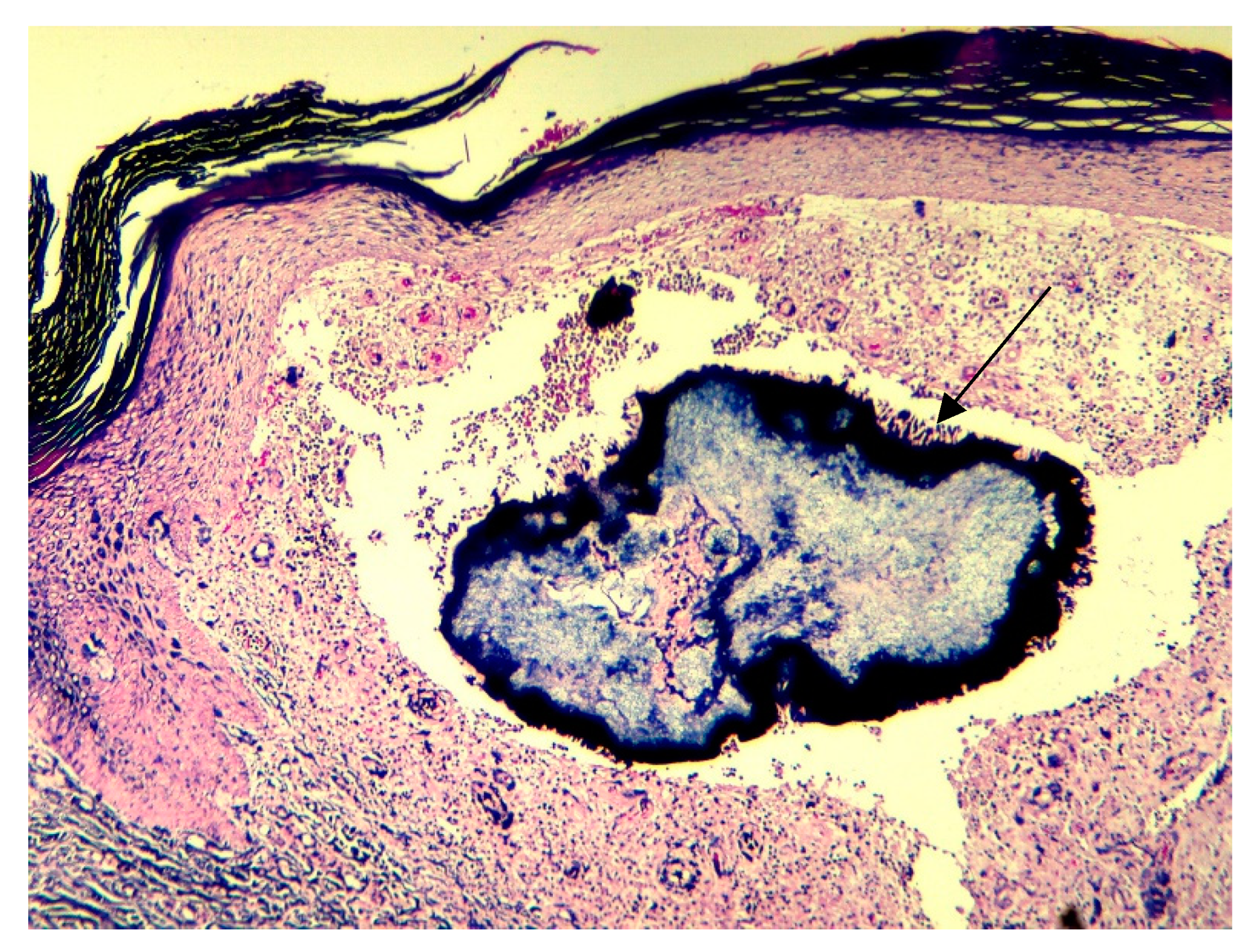

2. Case Report

3. Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valour, F.; Sénéchal, A.; Dupieux, C.; Karsenty, J.; Lustig, S.; Breton, P.; Gleizal, A.; Boussel, L.; Laurent, F.; Braun, E.; et al. Actinomycosis: Etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect. Drug Resist. 2014, 7, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Najmi, A.H.; Najmi, I.H.; Tawhari, M.M.H.; Sawadi, K.H.; Khbrani, K.A.H.; Tawhari, F.H.; Tawhari, M.A.; Mathkur, M.H.; Al-Attas, K.M. Cutaneous actinomycosis and long-term management through using oral and topical antibiotics: A case report. Clin. Pract. 2018, 8, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Almarzouq, S.F.; Almarghoub, M.A.; Almeshal, O. Primary actinomycosis of the big toe: A case report and literature review. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2019, 2019, rjz292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, V.; Turmezei, T.; Weston, V. Actinomycosis. BMJ 2011, 343, d6099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnefond, S.; Catroux, M.; Melenotte, C.; Karkowski, L.; Rolland, L.; Trouillier, S.; Raffray, L. Clinical features of actinomycosis: A retrospective, multicenter study of 28 cases of miscellaneous presentations. Medicine 2016, 95, e3923, Erratum in: Medicine 2016, 95, e5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sullivan, D.; Chapman, S. Bacteria that masquerade as fungi: Actinomycosis/nocardia. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2010, 7, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stájer, A.; Ibrahim, B.; Gajdács, M.; Urbán, E.; Baráth, Z. Diagnosis and management of cervicofacial actinomycosis: Lessons from two distinct clinical cases. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çarkman, S.; Ozben, V.; Durak, H.; Karabulut, K.; Ipek, T. Isolated abdominal wall actinomycosis associated with an intrauterine contraceptive device: A case report and review of the relevant literature. Case Rep. Med. 2010, 2010, 340109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Baierlein, S.A.; Wistop, A.; Looser, C.; Peters, T.; Riehle, H.M.; von Flüe, M.; Peterli, R. Abdominal actinomycosis: A rare complication after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes. Surg. 2007, 17, 1123–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Kim, S. Destruction of the c2 body due to cervical actinomycosis: Connection between spinal epidural abscess and retropharyngeal abscess. Korean J. Spine 2017, 14, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellazreg, F.; Hachfi, W.; Abdelkader, A.B.; Hattab, Z.; Kaabia, N.; Bahri, F.; Letaief, A. A mass shadow on chest X-ray in a 40-year-old man: What’s your diagnosis? Adv. Infect. Dis. 2012, 2, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettesworth, J.; Gill, K.; Shah, J. Primary actinomycosis of the foot: A case report and literature review. J. Am. Coll. Certif. Wound Spec. 2009, 1, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Choi, T.L.; Lui, T.H. Primary Actinomycosis of the Foot in a Patient with Neurofibromatosis. Foot Ankle Spec. 2011, 4, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boushabi, A.; Hicham, A.; Mohamed, S. Actinomycosis of the sole of the foot (Madura foot): A rare case report and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 113, 109052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ryu, D.J.; Jeon, Y.S.; Kwon, H.Y.; Choi, S.J.; Roh, T.H.; Kim, M.K. Actinomycotic osteomyelitis of a long bone in an immunocompetent adult: A case report and literature review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khan, S.; Khan, B.; Batool, W.; Khan, M.; Khan, A.H. Primary Cutaneous Actinomycosis: A Diagnostic Enigma. Cureus 2023, 15, e37261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dorobanțu, A.M.; Lupu, M.; Popa, L.G.; Tatar, R.; Giurcaneanu, C.; Tudose, I.; Orzan, O.A. Rare Presentation, Critical Diagnosis: Primary Actinomycosis of the Foot. Dermato 2024, 4, 72-78. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermato4030008

Dorobanțu AM, Lupu M, Popa LG, Tatar R, Giurcaneanu C, Tudose I, Orzan OA. Rare Presentation, Critical Diagnosis: Primary Actinomycosis of the Foot. Dermato. 2024; 4(3):72-78. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermato4030008

Chicago/Turabian StyleDorobanțu, Alexandra Maria, Mihai Lupu, Liliana Gabriela Popa, Raluca Tatar, Calin Giurcaneanu, Irina Tudose, and Olguta Anca Orzan. 2024. "Rare Presentation, Critical Diagnosis: Primary Actinomycosis of the Foot" Dermato 4, no. 3: 72-78. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermato4030008

APA StyleDorobanțu, A. M., Lupu, M., Popa, L. G., Tatar, R., Giurcaneanu, C., Tudose, I., & Orzan, O. A. (2024). Rare Presentation, Critical Diagnosis: Primary Actinomycosis of the Foot. Dermato, 4(3), 72-78. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermato4030008