Appropriate Prescription of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Geriatric Patients—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

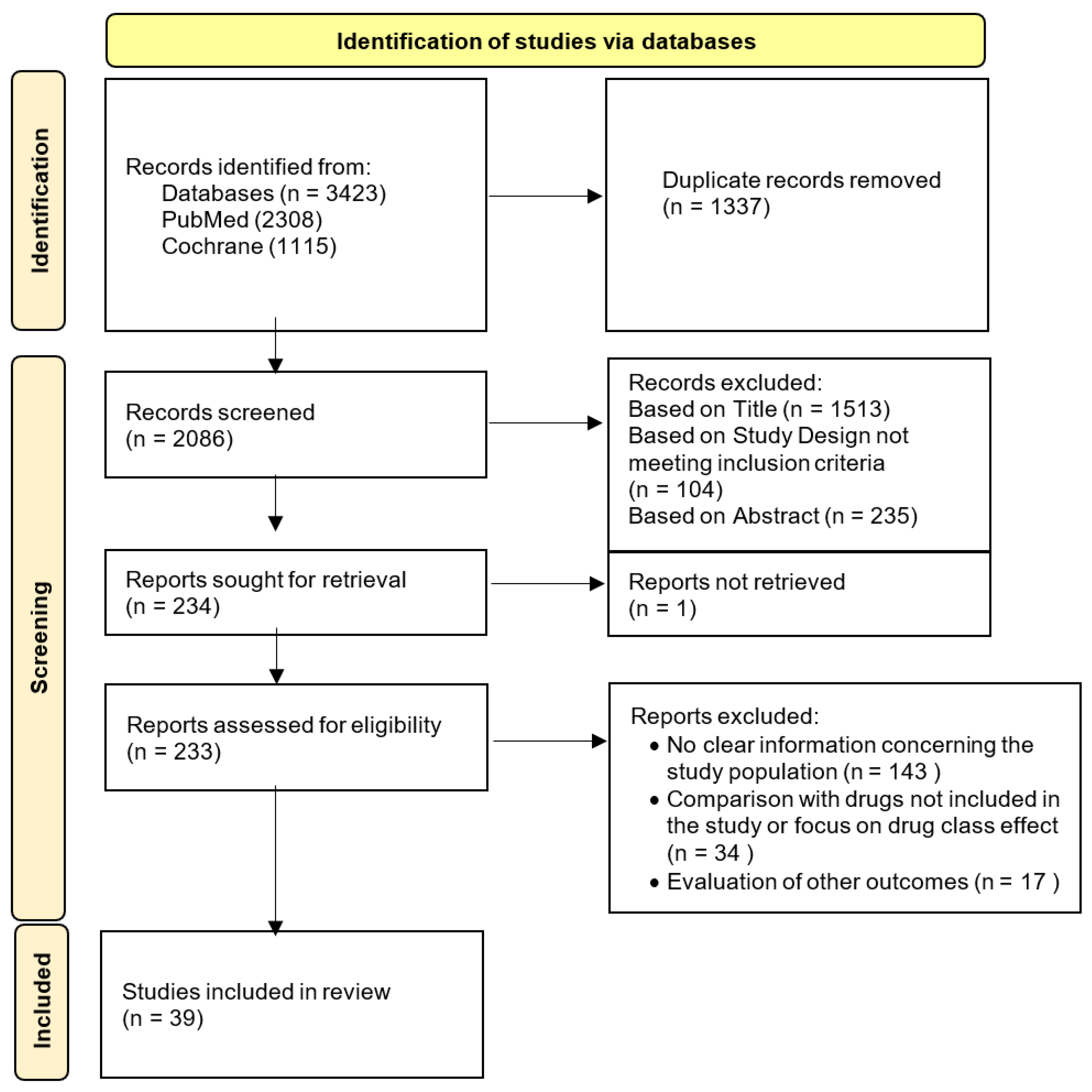

2. Methods

3. Results

| References | Year | Study Design | Population n (%) | Studied Drug of Interest (Dosage) | Main Findings in Population of Interest | SORT Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannon CP et al. [21] | 2006 | RCT | Overall = 34,701 ≥65 y = 14,397 (41.5%) | Diclofenac (150 mg/day) Etoricoxib (60 mg or 90 mg/day) | For elderly patients, the study suggests that the CV risk of etoricoxib is comparable to diclofenac. | 1 |

| Bertagnolli MM et al. [25] | 2009 | RCT | Overall = 2035 ≥65 y = ND | Celecoxib (200 mg 2id or 400 mg bid) | Patients aged 65 or older showed higher absolute risk for CV events. | 1 |

| Krum H, et al. [22] | 2009 | RCT | Overall = 34,695 ≥65 y = 14,386 (41.5%) | Diclofenac (150 mg id) Etoricoxib (60 or 90 mg id) | Older age increased the risk of CHF hospitalization. | 1 |

| Krum H, et al. [23] | 2009 | RCT | Overall = 23,498 ≥65 y = 9998 (42.5%) | Diclofenac (150 mg id) Etoricoxib (60 or 90 mg id) | Age at least 65 years was strongly associated with increased BP. | 1 |

| Mamdani M et al. [35] | 2003 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Overall = 593,808 ≥65 y = 593,808 (100%) | Celecoxib (ND) Naproxen (ND) | No significant differences in AMI rates were observed between celecoxib and naproxen. The findings do not support a short-term reduced risk of AMI with naproxen. | 2 |

| Lévesque LE et al. [33] | 2005 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Overall = 113,927 ≥65 y = 113,927 (100%) | Celecoxib (≤200 mg or >200 mg/day) Naproxen (ND) | The study found no increased risk among users of celecoxib, regardless of the dose prescribed. Naproxen was not associated with an increased CV risk or benefit. | 2 |

| Hudson M et al. [43] | 2005 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Overall = 18,503 ≥65 y = 18,503 (100%) | Ibuprofen (ND) Naproxen (ND) | Trend toward an increase in the rate of recurrent AMI with longer duration of ibuprofen exposure. Trend toward a lower rate of recurrent AMI in patients taking naproxen and AAS compared to AAS alone. | 2 |

| Solomon DH, et al. [31] | 2006 | Longitudinal CohortStudy | Overall = 74,838 ≥65 y = 74,838 (100%) | Celecoxib low ≤ 200 mg, high > 200 mg Ibuprofen, Diclofenac and Naproxen (low ≤ 75% of the maximum anti-inflammatory dosage, high > 75%) | Naproxen showed a protective effect against CV events, particularly compared to diclofenac and ibuprofen.Diclofenac was associated with a higher risk of AMI, though not significantly different for overall CV events. | 2 |

| Lévesque LE et al. [44] | 2006 | Population-Based Cohort Study | Overall = 113,927 ≥65 y = 113,927 (100%) | Celecoxib (ND) | The risk increase for first-time use of celecoxib was not statistically significant. | 2 |

| Rahme E et al. [45] | 2007 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Overall = 283,799 ≥65 y = 283,799 (100%) | Celecoxib (≤200 mg/day vs. >200 mg/day OR 400 mg/day vs. >400 mg/day) Diclofenac (≤150 mg/day vs. >150 mg/day) and Ibuprofen (≤1600 mg/day vs. >1600 mg/day) | Study suggests that celecoxib does not confer a higher CV risk compared to ibuprofen and diclofenac. | 2 |

| Hudson M et al. [34] | 2007 | Case-Control Study | Overall = 42,560 ≥65 y = 42,560 (100%) | Celecoxib (≤200 mg id and >200 mg/day) Diclofenac (≤100 mg id and >100 mg/day) Ibuprofen (≤1200 mg id and >1200 mg/day) Naproxen (≤500 mg id and >500 mg/day) | Risks of recurrent CHF in patients exposed to naproxen, diclofenac, and ibuprofen were not significantly different compared with those of patients exposed to celecoxib at target doses. | 2 |

| Abraham NS et al. [46] | 2007 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Overall = 384,322 ≥65 y = 384,322 (100%) | Celecoxib (200 mg median daily dose) Ibuprofen (1800 mg median daily dose) Naproxen (1000 mg median daily dose) | Celecoxib was associated with a non-significant increase in the risk of AMI or cerebrovascular accident compared to naproxen. Ibuprofen showed a slightly higher risk of AMI compared to naproxen but had a similar risk for cerebrovascular accident compared to naproxen. | 2 |

| Solomon DH, et al. [47] | 2008 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Overall = 76,082 ≥65 y = 76,082 (100%) | Celecoxib (ND) Diclofenac (ND) Ibuprofen (ND) Naproxen (ND) | Ibuprofen appeared to confer an increased CVR in patients aged ≥80 years. | 2 |

| Cunnington M et al. [24] | 2008 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Overall = 80,826 ≥65 y = 39,048 (48.3%) | Celecoxib (ND) Naproxen (ND) | One of the strongest predictors of AMI/ ischemic stroke risk was age >65 years. | 2 |

| Mangoni AA, et al. [48] | 2010 | Retrospective Case-Control Study | Overall = 138,774 ≥65 y = 138,774 (100%) | Celecoxib (ND) Diclofenac (ND) Ibuprofen (ND) Naproxen (ND) | Neither naproxen or celecoxib showed a significant association with the risk of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Low to moderate use of ibuprofen and diclofenac may be associated with a reduced risk of ischemic stroke. | 2 |

| Mangoni AA, et al. [49] | 2010 | Retrospective Case-Control Study | Overall = 138,774 ≥65 y = 138,774 (100%) | Celecoxib (ND) Diclofenac (ND) Ibuprofen (ND) Naproxen (ND) | There was an increase in the risk of AMI with increasing supplies of the individual NSAIDs naproxen and ibuprofen, but not for diclofenac.Analysis of the individual NSAIDs showed a reduced risk of cardiac arrest associated with low exposure to diclofenac and an increased risk of arrhythmias associated with moderate-high exposure to naproxen. | 2 |

| Schjerning et al. [50] | 2011 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Overall = 83,677 ≥65 y = ND | Celecoxib (ND) Diclofenac (ND) Ibuprofen (ND) Naproxen (ND) | Age-stratified analysis found that patients ≥80 years of age had a higher risk of death during the first week of treatment when taking diclofenac compared to younger patients. | 2 |

| Caughey GE, et al. [38] | 2011 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Overall = 162,065 ≥65 y = 162,065 (100%) | Diclofenac (ND) Ibuprofen (ND) | An increased risk of stroke was observed with diclofenac. Ibuprofen was not associated with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. | 2 |

| Lee T, et al. [37] | 2016 | Case-control Study | Overall = 24,079 ≥70 y = 15,435 (64.1%) | Celecoxib (ND) Diclofenac (ND) Ibuprofen (ND) Naproxen (ND) | Among current users, risk of venous thromboembolism was increased in diclofenac and ibuprofen. However, such association was not observed among current naproxen users. | 2 |

| Schmidt M, et al. [36] | 2018 | Emulated Trial | Overall = 7,608,766 ≥70 y = 779,250 (10.2%) | Diclofenac (ND) Ibuprofen (ND) Naproxen (ND) | The increased risk of major adverse CV events with diclofenac initiation was consistent in the elderly subgroups compared to ibuprofen, naproxen, and non-use. | 2 |

| References | Year | Study Design | Population n (%) | Studied Drugs of Interest (Dosage) | Main Findings in Population of Interest | SORT Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goldstein JL et al. [51] | 2003 | RCT | Overall = 186 ≥65 y = 186 (100%) | Naproxen (500 mg bid) | Naproxen use was associated with a significantly higher incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers and erosions compared to placebo. | 1 |

| Laine L et al. [52] | 2004 | RCT | Overall = 1519 ≥65 y = 467 (30.7%) | Ibuprofen (800 mg bid) | No significant treatment-by-subgroup interaction was seen for ulcer risk factors, including age ≥ 65 years. Rates of discontinuation and gastroduodenal ulcers and erosions were significantly higher in the ibuprofen group compared with placebo group. | 1 |

| Chan FK et al. [27] | 2004 | RCT | Overall = 287 ≥65 y = ND | Celecoxib (200 mg bid) Diclofenac (75 mg bid) | Age ≥ 75 years was an independent riskfactor predicting ulcer recurrence. | 1 |

| Lai KC et al. [28] | 2005 | RCT | Overall = 242 ≥65 y = 81 (33.5%) | Celecoxib (200 mg/day) Naproxen (750 mg/day) | Celecoxib was not inferior to lansoprazole plus naproxen in preventing GI ulcer complications, including those aged 65 or older. Age 65 years or more was an independent risk factor for ulcer recurrence. | 1 |

| Laine L et al. [53] | 2008 | Prospective Cohort Trial | Overall = 34,701 ≥65 y = 14,396 (41.5%) | Diclofenac (150 mg/day) Etoricoxib (60 or 90 m/day) | Older age was a significant predictor for lower GI clinical events, with a 2-fold increase in risk. | 1 |

| Laine L e at. [26] | 2010 | RCT | Overall = 34,701 ≥65 y = 14,227 (41.0%) | Diclofenac (150 mg/day) Etoricoxib (60 or 90 mg/day) | Age ≥ 65 years was a significant predictor of discontinuation due to dyspepsia, clinical events, and complicated events. | 1 |

| Arber N et al. [54] | 2012 | RCT | Overall = 3588 ≥65 y = 29.7% (APC Study); 37.9% (PreSAP study) | Celecoxib (200 mg/400 mg bid or 400 mg id) | Age ≥65 years was associated with an increased risk of GI events in both celecoxib and placebo groups. The noninferiority of celecoxib to placebo was not established. | 1 |

| Kellner HL et al. [40] | 2012 | RCT | Overall = 2446 ≥65 y = 2446 (100%) | Celecoxib (200 mg bid) Diclofenac (75 mg bid) | Celecoxib was associated with significantly fewer clinically significant upper and lower GI events compared with diclofenac plus omeprazole in patients aged ≥65 years. | 1 |

| Couto A et al. [55] | 2018 | RCT | Overall = 818 ≥65 y = 358 (43.7%) | Naproxen (220 mg bid) | The rate of reported GI AE was comparable in the naproxen and placebo groups for all age groups. | 1 |

| Kyeremateng K et al. [29] | 2019 | Retrospective Pooled Analysis of RCTs | Overall = 1494 ≥65 y = 544 (36.4%) | Naproxen (440 mg/day) Ibuprofen (600–1200 mg/day) | In ≥65 years there was no difference in the overall rate or type of AE compared with younger participants. There were no significant differences in overall adverse events between naproxen, placebo or ibuprofen. | 1 |

| Biskupiak JE et al. [56] | 2006 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Overall = 60,212 ≥65 y = ND | Ibuprofen (ND) Naproxen (ND) | Elderly patients had a higher incidence of serious GI toxicities compared to younger adults both with naproxen and ibuprofen. | 2 |

| Schneeweiss S et al. [32] | 2006 | Population-Based Cohort Study | Overall = 49,711 ≥65 y = 49,711 (100%) | Celecoxib (ND) Diclofenac (ND) Naproxen (ND) Ibuprofen (ND) | Celecoxib produces a significant short-term reduction in GI complications compared with all nonselective NSAIDs combined. Diclofenac appears to have the least favorable safety profile among individual NSAIDs. The risk of AMI was significantly higher for diclofenac compared to celecoxib, while ibuprofen did not show a significant difference in AMI risk when compared to celecoxib. Naproxen may have a more favorable CV safety profile compared to celecoxib, indicated by the lowest risk difference for MI among the NSAIDs studied, although this difference was not statistically significant. | 2 |

| Hsiang KW et al. [30] | 2010 | Prospective Observational Cohort Study | Overall = 933 ≥70 y = 490 (49.3%) | Celecoxib (100–400 mg/day) Etoricoxib (60 mg/day) | Age >60 or >70 years was not a risk factor for symptomatic ulcers and ulcer complications in COX-2 inhibitor users. Use of COX-2 inhibitors was well tolerated in regard to the upper GI tract in patients aged >70 years. | 2 |

| Sostek MB et al. [57] | 2011 | Open-label, Multicenter, Phase III Study | Overall = 239 ≥65 y = 78 (32.6%) | Naproxen (500 mg bid) | Twice-daily dosing with naproxen/esomeprazole was not associated with any new or unexpected safety issues. Subgroup analysis suggest that the safety profile of naproxen/esomeprazole is similar in <65 vs. ≥65 years old patients. | 2 |

| Chang CH et al. [39] | 2011 | Case-Crossover Study | Overall = 40,635 ≥65 y = ND | Celecoxib (ND) | Celecoxib was associated with higher risk of upper GI events vs. non-use. Elderly were at higher risk for upper GI adverse events. | 2 |

| References | Year | Study Design | Population n (%) | Studied Drug (Dosage) | Main Findings in Population of Interest | SORT Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juhlin T et al. [41] | 2004 | RCT | Overall = 14 ≥65 y = 14 (100%) | Diclofenac (50 mg id) | Diclofenac caused significant reductions in GFR, urine flow, and excretion rates of sodium and potassium. Pre-treatment with diuretics and ACE-inhibitors exacerbated this impact. | 2 |

| Schneider V et al. [42] | 2006 | Case-Control Study | Overall = 121,722 ≥65 y = 121,722 (100%) | Celecoxib (low dose 200 mg id // high dose >200 mg id) Naproxen (low dose 750 mg id // high dose >750 mg id) | Both celecoxib and naproxen show a dose-dependent increase in the risk of AKI. However, the risk increase is more pronounced with higher doses of naproxen. The study suggests that celecoxib is associated with a lower risk of AKI compared to naproxen, especially at lower doses. | 2 |

| Winkelmayer WC et al. [58] | 2008 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Overall = 183,446 ≥65 y = 183,446 (100%) | Celecoxib (ND) Diclofenac (ND) Naproxen (ND) Ibuprofen (ND) | Ibuprofen seemed to have a greater rate of AKI compared with celecoxib. | 2 |

| Benson P et al. [59] | 2012 | Prospective observational study | Overall = 44 ≥65 y = 44 (100%) | Celecoxib (400 mg bid) | High-dose celecoxib was relatively well-tolerated by elderly patients, with stable renal function and minor electrolyte alterations. | 2 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jain, N.; Kourampi, I.; Umar, T.P.; Almansoor, Z.R.; Anand, A.; Ur Rehman, M.E.; Jain, S.; Reinis, A. Global population surpasses eight billion: Are we ready for the next billion? AIMS Public Health 2023, 10, 849–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Eurostat Statistics Explained, July 2020, Ageing Europe—Statistics on Population Developments. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_introduction (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- PORDATA. População Residente: Total e por Grandes Grupos Etários. 2024. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/pt/estatisticas/populacao/populacao-residente/populacao-residente-por-sexo-e-grupo-etario (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q.A. Aging Hallmarks and Progression and Age-Related Diseases: A Landscape View of Research Advancement. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, H.; Rodrigues, I.; Napoleão, L.; Lira, L.; Marques, D.; Veríssimo, M.; Andrade, J.P.; Dourado, M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), pain and aging: Adjusting prescription to patient features. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 112958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zazzara, M.B.; Palmer, K.; Vetrano, D.L.; Carfì, A.; Onder, G. Adverse drug reactions in older adults: A narrative review of the literature. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialová, D.; Laffon, B.; Marinković, V.; Tasić, L.; Doro, P.; Sόos, G.; Mota, J.; Dogan, S.; Brkic, J.; Teixeira, J.P.; et al. Medication use in older patients and age-blind approach: Narrative literature review (insufficient evidence on the efficacy and safety of drugs in older age, frequent use of PIMs and polypharmacy, and underuse of highly beneficial nonpharmacological strategies). Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 75, 451–466. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, L.F.; Costa-Pereira, A.; Mendonça, L.; Dias, C.C.; Castro-Lopes, J.M. Epidemiology of chronic pain: A population-based nationwide study on its prevalence, characteristics and associated disability in Portugal. J. Pain 2012, 13, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.C.; Eccleston, C.; Pillemer, K. Management of chronic pain in older adults. BMJ 2015, 350, h532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, R.; Mathew, M.; Patel, K.K.; Reddy, S.A.; Haider, Z.; Naria, M.; Habib, A.; Abdin, Z.U.; Chaudhry, W.R.; Akbar, A. Effects of Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) and Gastroprotective NSAIDs on the Gastrointestinal Tract: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e37080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeto, C.C.; Sugano, K.; Wang, J.G.; Fujimoto, K.; Whittle, S.; Modi, G.K.; Chen, C.-H.; Park, J.-B.; Tam, L.-S.; Vareesangthip, K.; et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy in patients with hypertension, cardiovascular, renal or gastrointestinal comorbidities: Joint APAGE/APLAR/APSDE/APSH/APSN/PoA recommendations. Gut 2020, 69, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, K.; Patrignani, P. New insights into the use of currently available non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J. Pain Res. 2015, 8, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghi, A.; Arfaei, S. Selective COX-2 Inhibitors: A Review of Their Structure-Activity Relationships. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2011, 10, 655–683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Conaghan, P.G. A turbulent decade for NSAIDs: Update on current concepts of classification, epidemiology, comparative efficacy, and toxicity. Rheumatol. Int. 2012, 32, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saúde, D.G.d. Anti-Inflamatórios não Esteroides Sistémicos em Adultos: Orientações para a Utilização de Inibidores da COX-2. 2013. Available online: https://normas.dgs.min-saude.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/anti-inflamatorios-nao-esteroides-sistemicos-em-adultos-orientacoes-para-a-utilizacao-de-inibidores-da-cox.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Minhas, D.; Nidhaan, A.; Husni, M.E. Recommendations for the Use of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Decades Later, Any New Lessons Learned? Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 49, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Service N-NH. Oral Non-Steroidal Antiinflammatory (NSAID) Guidelines. 2020. Available online: https://www.nhsggc.org.uk/media/254733/oral-non-steroidal-anti-inflammatory-nsaid-guideline.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Monteiro, C.; Silvestre, S.; Duarte, A.P.; Alves, G. Safety of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in the Elderly: An Analysis of Published Literature and Reports Sent to the Portuguese Pharmacovigilance System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebell, M.H.; Siwek, J.; Weiss, B.D.; Woolf, S.H.; Susman, J.; Ewigman, B.; Bowman, M. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): A patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J. Am. Board Fam. Pract. 2004, 17, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, C.P.; Curtis, S.P.; Bolognese, J.A.; Laine, L. Clinical trial design and patient demographics of the Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term (MEDAL) study program: Cardiovascular outcomes with etoricoxib versus diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Am. Heart J. 2006, 152, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krum, H.; Curtis, S.P.; Kaur, A.; Wang, H.; Smugar, S.S.; Weir, M.R.; Laine, L.; Brater, D.C.; Cannon, C. Baseline factors associated with congestive heart failure in patients receiving etoricoxib or diclofenac: Multivariate analysis of the MEDAL program. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2009, 11, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krum, H.; Swergold, G.; Curtis, S.P.; Kaur, A.; Wang, H.; Smugar, S.S.; Weir, M.; Laine, L.; Brater, D.C.; Cannon, C. Factors associated with blood pressure changes in patients receiving diclofenac or etoricoxib: Results from the MEDAL study. J. Hypertens. 2009, 27, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnington, M.; Webb, D.; Qizilbash, N.; Blum, D.; Mander, A.; Funk, M.J.; Weil, J. Risk of ischaemic cardiovascular events from selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in osteoarthritis. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2008, 17, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertagnolli, M.M.; Eagle, C.J.; Zauber, A.G.; Redston, M.; Breazna, A.; Kim, K.; Tang, J.; Rosenstein, R.B.; Umar, A.; Bagheri, D.; et al. Five-year efficacy and safety analysis of the Adenoma Prevention with Celecoxib Trial. Cancer Prev. Res. 2009, 2, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laine, L.; Curtis, S.P.; Cryer, B.; Kaur, A.; Cannon, C.P. Risk factors for NSAID-associated upper GI clinical events in a long-term prospective study of 34 701 arthritis patients. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 32, 1240–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, F.K.; Hung, L.C.; Suen, B.Y.; Wong, V.W.; Hui, A.J.; Wu, J.C.; Leung, W.K.; Lee, Y.T.; To, K.F.; Chung, S.C.S.; et al. Celecoxib versus diclofenac plus omeprazole in high-risk arthritis patients: Results of a randomized double-blind trial. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, K.C.; Chu, K.M.; Hui, W.M.; Wong, B.C.; Hu, W.H.; Wong, W.M.; Lam, S.-K. Celecoxib compared with lansoprazole and naproxen to prevent gastrointestinal ulcer complications. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyeremateng, K.; Troullos, E.; Paredes-Diaz, A. Safety of naproxen compared with placebo, ibuprofen and acetaminophen: A pooled analysis of eight multiple-dose, short-term, randomized controlled studies. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2019, 35, 1671–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, K.W.; Chen, T.S.; Lin, H.Y.; Luo, J.C.; Lu, C.L.; Lin, H.C.; Lee, K.C.; Chang, F.Y.; Lee, S.D. Incidence and possible risk factors for clinical upper gastrointestinal events in patients taking selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: A prospective, observational, cohort study in Taiwan. Clin. Ther. 2010, 32, 1294–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, D.H.; Avorn, J.; Stürmer, T.; Glynn, R.J.; Mogun, H.; Schneeweiss, S. Cardiovascular outcomes in new users of coxibs and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: High-risk subgroups and time course of risk. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneeweiss, S.; Solomon, D.H.; Wang, P.S.; Rassen, J.; Brookhart, M.A. Simultaneous assessment of short-term gastrointestinal benefits and cardiovascular risks of selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors and nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: An instrumental variable analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 3390–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, L.E.; Brophy, J.M.; Zhang, B. The risk for myocardial infarction with cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: A population study of elderly adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 142, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M.; Rahme, E.; Richard, H.; Pilote, L. Risk of congestive heart failure with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and selective Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors: A class effect? Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamdani, M.; Rochon, P.; Juurlink, D.N.; Anderson, G.M.; Kopp, A.; Naglie, G.; Austin, P.C.; Laupacis, A. Effect of selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors and naproxen on short-term risk of acute myocardial infarction in the elderly. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Sørensen, H.T.; Pedersen, L. Diclofenac use and cardiovascular risks: Series of nationwide cohort studies. BMJ 2018, 362, k3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.; Lu, N.; Felson, D.T.; Choi, H.K.; Dalal, D.S.; Zhang, Y.; Dubreuil, M. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs correlates with the risk of venous thromboembolism in knee osteoarthritis patients: A UK population-based case-control study. Rheumatology 2016, 55, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughey, G.E.; Roughead, E.E.; Pratt, N.; Killer, G.; Gilbert, A.L. Stroke risk and NSAIDs: An Australian population-based study. Med. J. Aust. 2011, 195, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Chen, H.C.; Lin, J.W.; Kuo, C.W.; Shau, W.Y.; Lai, M.S. Risk of hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal adverse events associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: A nationwide case-crossover study in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2011, 20, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, H.L.; Li, C.; Essex, M.N. Efficacy and safety of celecoxib versus diclofenac and omeprazole in elderly arthritis patients: A subgroup analysis of the CONDOR trial. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2012, 28, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhlin, T.; Björkman, S.; Höglund, P. Cyclooxygenase inhibition causes marked impairment of renal function in elderly subjects treated with diuretics and ACE-inhibitors. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2005, 7, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schneider, V.; Lévesque, L.E.; Zhang, B.; Hutchinson, T.; Brophy, J.M. Association of selective and conventional nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs with acute renal failure: A population-based, nested case-control analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 164, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M.; Baron, M.; Rahme, E.; Pilote, L. Ibuprofen may abrogate the benefits of aspirin when used for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction. J. Rheumatol. 2005, 32, 1589–1593. [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque, L.E.; Brophy, J.M.; Zhang, B. Time variations in the risk of myocardial infarction among elderly users of COX-2 inhibitors. CMAJ 2006, 174, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahme, E.; Watson, D.J.; Kong, S.X.; Toubouti, Y.; LeLorier, J. Association between nonnaproxen NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors and hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction among the elderly: A retrospective cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2007, 16, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, N.S.; El-Serag, H.B.; Hartman, C.; Richardson, P.; Deswal, A. Cyclooxygenase-2 selectivity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accident. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 25, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, D.H.; Glynn, R.J.; Rothman, K.J.; Schneeweiss, S.; Setoguchi, S.; Mogun, H.; Avorn, J.; Sturmer, T. Subgroup analyses to determine cardiovascular risk associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and coxibs in specific patient groups. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangoni, A.A.; Woodman, R.J.; Gilbert, A.L.; Knights, K.M. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in the Australian veteran community. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2010, 19, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangoni, A.A.; Woodman, R.J.; Gaganis, P.; Gilbert, A.L.; Knights, K.M. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of incident myocardial infarction and heart failure, and all-cause mortality in the Australian veteran community. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 69, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schjerning Olsen, A.M.; Fosbøl, E.L.; Lindhardsen, J.; Folke, F.; Charlot, M.; Selmer, C.; Laberts, M.; Olesen, J.B.; Køber, L.; Hansen, P.R.; et al. Duration of treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and impact on risk of death and recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with prior myocardial infarction: A nationwide cohort study. Circulation 2011, 123, 2226–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.L.; Kivitz, A.J.; Verburg, K.M.; Recker, D.P.; Palmer, R.C.; Kent, J.D. A comparison of the upper gastrointestinal mucosal effects of valdecoxib, naproxen and placebo in healthy elderly subjects. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 18, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, L.; Maller, E.S.; Yu, C.; Quan, H.; Simon, T. Ulcer formation with low-dose enteric-coated aspirin and the effect of COX-2 selective inhibition: A double-blind trial. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, L.; Curtis, S.P.; Langman, M.; Jensen, D.M.; Cryer, B.; Kaur, A.; Cannon, C.P. Lower gastrointestinal events in a double-blind trial of the cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective inhibitor etoricoxib and the traditional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, N.; Lieberman, D.; Wang, T.C.; Zhang, R.; Sands, G.H.; Bertagnolli, M.M.; Hawk, E.T.; Eagle, C.; Coindreau, J.; Zauber, A.; et al. The APC and PreSAP trials: A post hoc noninferiority analysis using a comprehensive new measure for gastrointestinal tract injury in 2 randomized, double-blind studies comparing celecoxib and placebo. Clin. Ther. 2012, 34, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, A.; Troullos, E.; Moon, J.; Paredes-Diaz, A.; An, R. Analgesic efficacy and safety of non-prescription doses of naproxen sodium in the management of moderate osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2018, 34, 1747–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biskupiak, J.E.; Brixner, D.I.; Howard, K.; Oderda, G.M. Gastrointestinal complications of over-the-counter nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2006, 20, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sostek, M.B.; Fort, J.G.; Estborn, L.; Vikman, K. Long-term safety of naproxen and esomeprazole magnesium fixed-dose combination: Phase III study in patients at risk for NSAID-associated gastric ulcers. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2011, 27, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelmayer, W.C.; Waikar, S.S.; Mogun, H.; Solomon, D.H. Nonselective and cyclooxygenase-2-selective NSAIDs and acute kidney injury. Am. J. Med. 2008, 121, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P.; Yudd, M.; Sims, D.; Chang, V.; Srinivas, S.; Kasimis, B. Renal effects of high-dose celecoxib in elderly men with stage D2 prostate carcinoma. Clin. Nephrol. 2012, 78, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumic, I.; Nordin, T.; Jecmenica, M.; Stojkovic Lalosevic, M.; Milosavljevic, T.; Milovanovic, T. Gastrointestinal Tract Disorders in Older Age. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 2019, 6757524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, J.L. Effect of age-related changes in gastric physiology on tolerability of medications for older people. Drugs Aging 2005, 22, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Piña, A.E.; McKnight, W.; Dicay, M.; Castañeda-Hernández, G.; Wallace, J.L. Mechanisms underlying the anti-inflammatory activity and gastric safety of acemetacin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 152, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costa, C.; Soares, D.; Borges, A.; Gonçalves, A.; Andrade, J.P.; Ribeiro, H. Appropriate Prescription of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Geriatric Patients—A Systematic Review. BioChem 2024, 4, 300-312. https://doi.org/10.3390/biochem4040015

Costa C, Soares D, Borges A, Gonçalves A, Andrade JP, Ribeiro H. Appropriate Prescription of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Geriatric Patients—A Systematic Review. BioChem. 2024; 4(4):300-312. https://doi.org/10.3390/biochem4040015

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosta, Carolina, Diana Soares, Ana Borges, Ana Gonçalves, José Paulo Andrade, and Hugo Ribeiro. 2024. "Appropriate Prescription of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Geriatric Patients—A Systematic Review" BioChem 4, no. 4: 300-312. https://doi.org/10.3390/biochem4040015

APA StyleCosta, C., Soares, D., Borges, A., Gonçalves, A., Andrade, J. P., & Ribeiro, H. (2024). Appropriate Prescription of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Geriatric Patients—A Systematic Review. BioChem, 4(4), 300-312. https://doi.org/10.3390/biochem4040015