Consistency and Rheological Properties of Cemented Paste Backfills Prepared with Tailings with Varying Free Muscovite Content

Abstract

1. Introduction

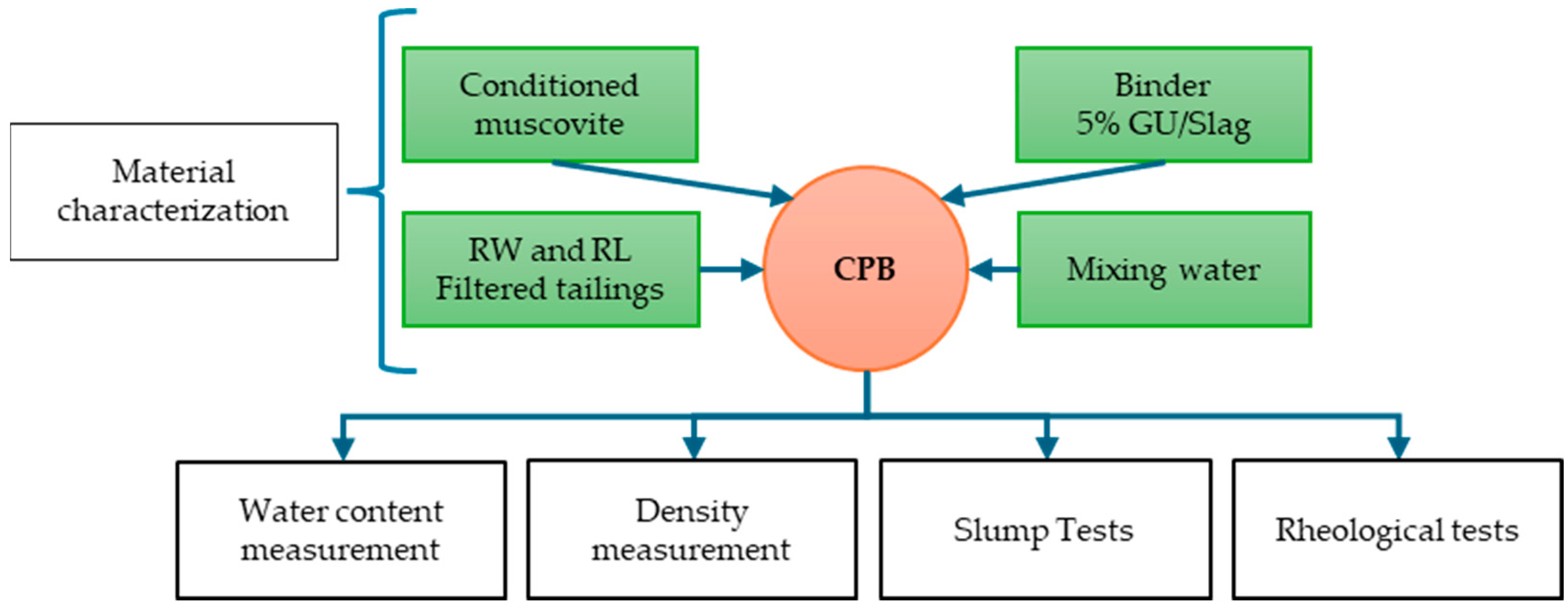

2. Material Characterization and Methodology

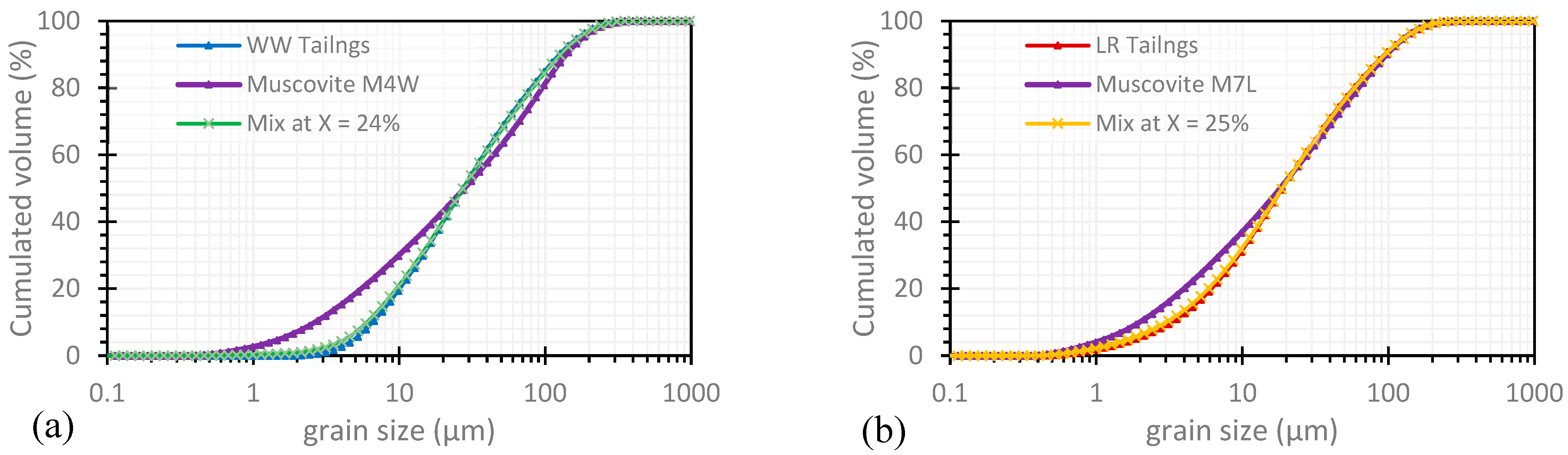

2.1. Physical Characterization of Mine Tailings and Muscovite

2.2. Mineralogical Characterization of Tailings and Muscovite

2.3. Mixture Preparation

2.4. Measurement of Cone Slumps

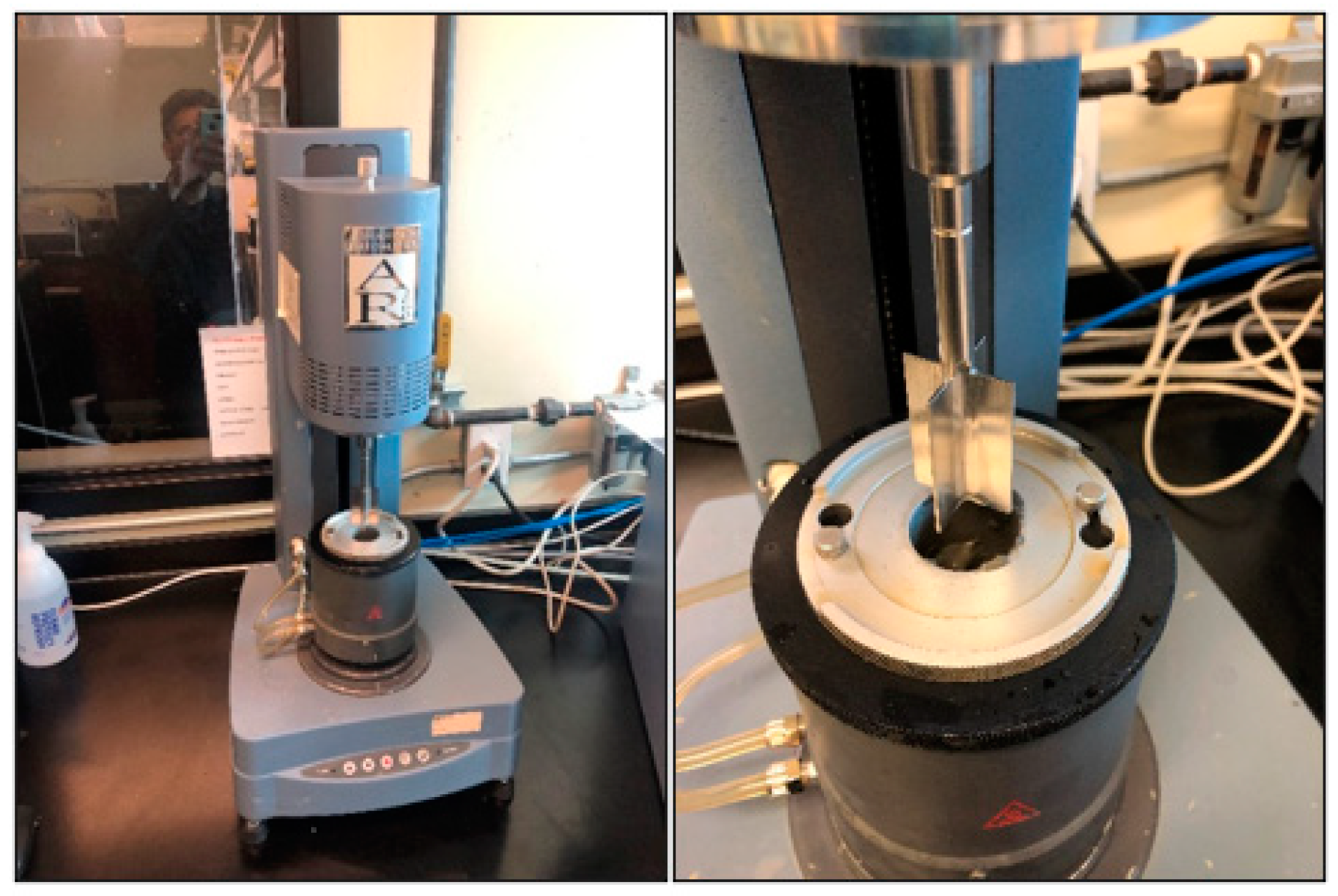

2.5. Rheological Measurements and Analysis

3. Experimental Results

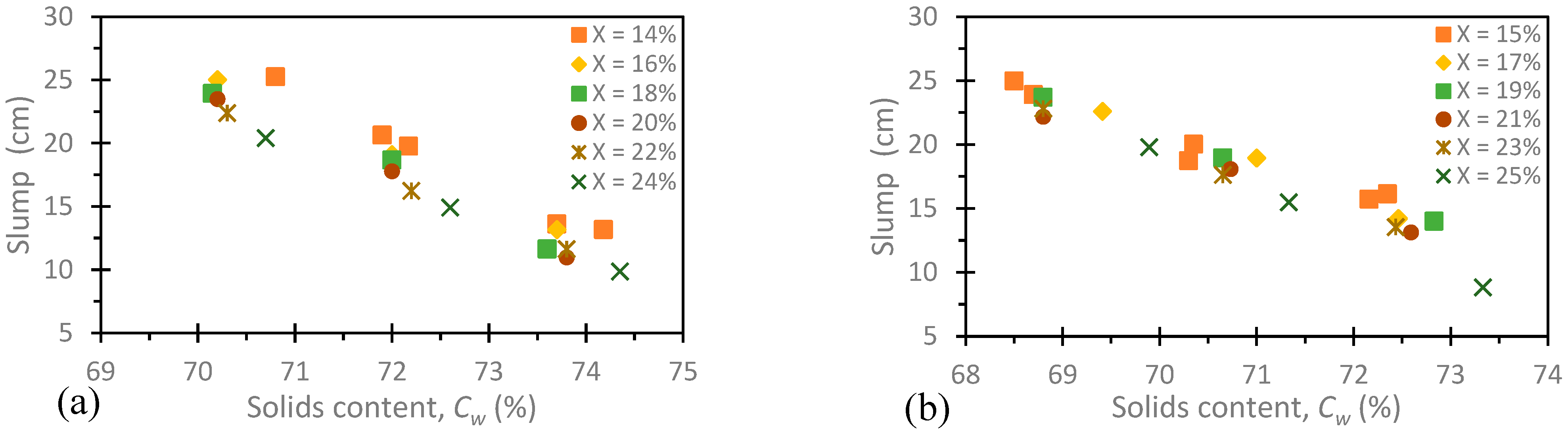

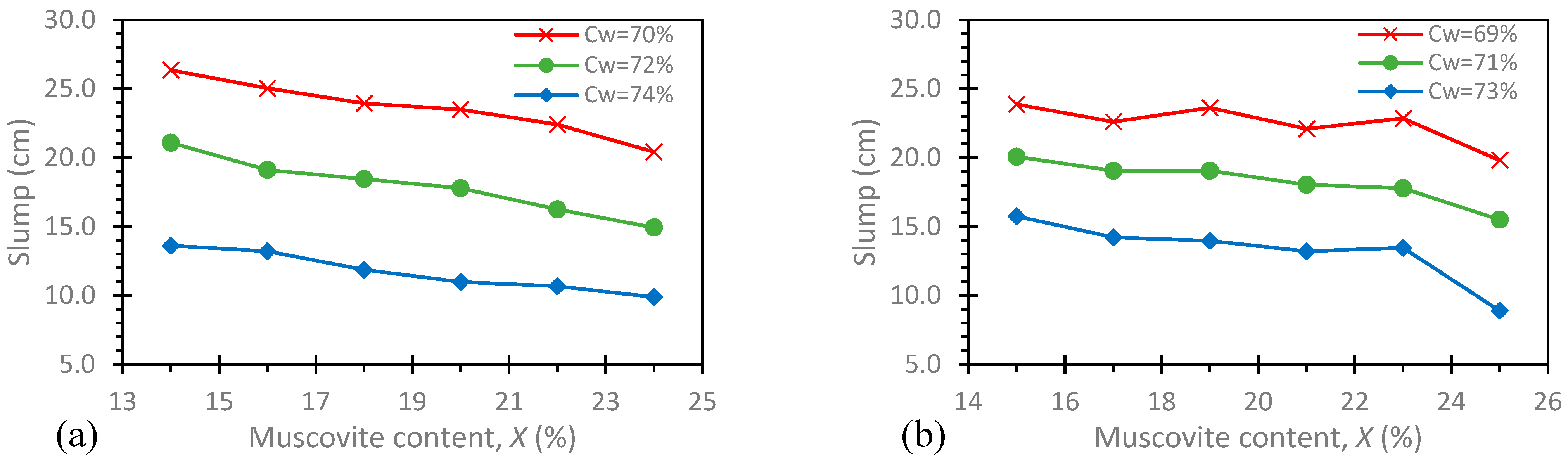

3.1. Effect of Solid and Muscovite Contents on the Abrams Cone Slump of CPB Mixtures

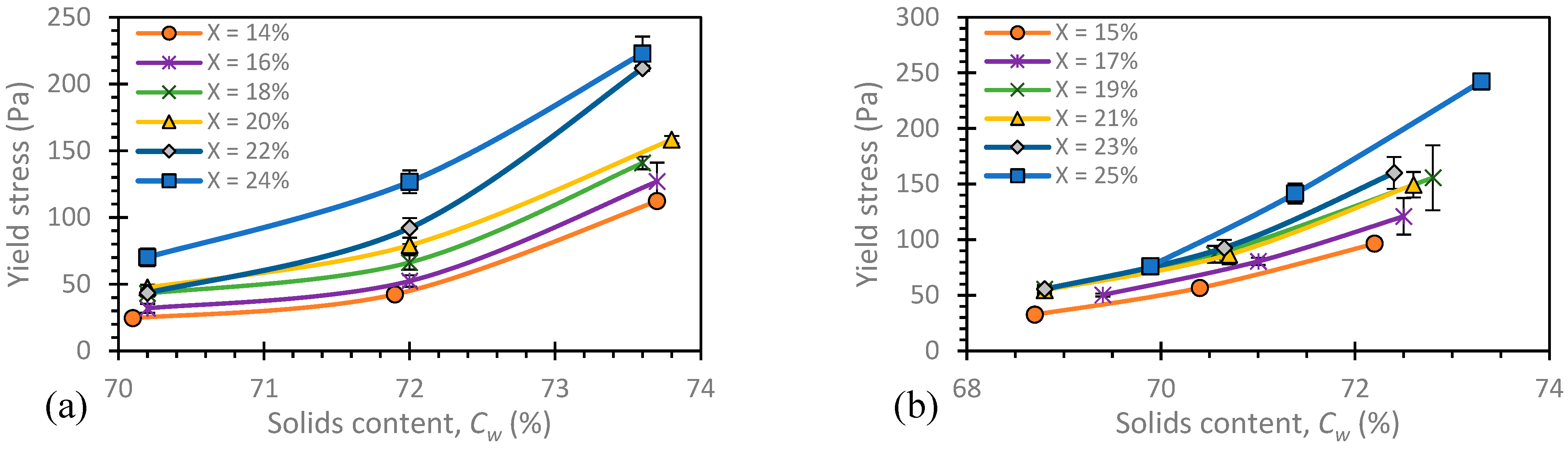

3.2. Effect of Solids Content and Muscovite Content on Flow Curves

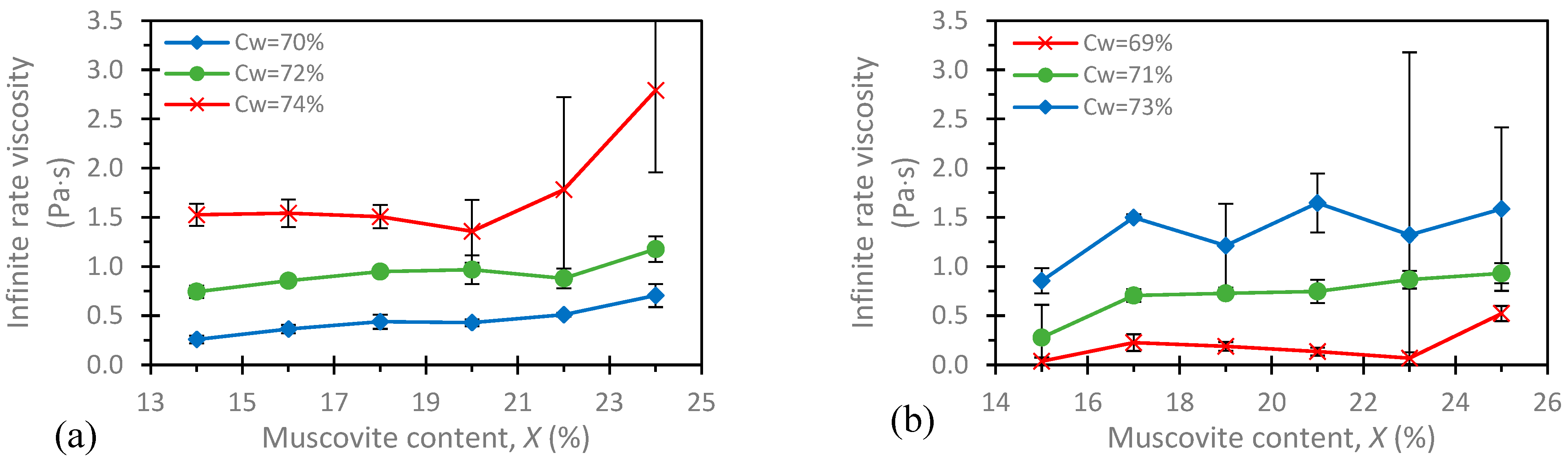

3.3. Effect of Solid and Muscovite Contents on Dynamic Viscosity Curves

4. Discussion of the Results

4.1. Impact of Muscovite Content on the Solids Content Required to Maintain a Given Slump of CPB Mixtures

4.2. Effect of Tailings Type

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Institut de la Statistique du Québec (ISQ) 2021. La Production Minérale au Québec en. 2019. Available online: https://statistique.quebec.ca/fr/fichier/mines-en-chiffres-production-minerale-quebec-2019.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Bussiere, B. Hydrogeotechnical properties of hard rock tailings from metal mines and emerging geoenvironmental disposal approaches. Can. Geotech. J. 2007, 44, 1019–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinsky, E.; Barbour, S.L.; Wilson, G.W.; Bordin, D.; Fredlund, D.G. Thickened sloped tailings disposal: An evaluation of seepage and abatement of acid drainage. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on the Abatement of Acidic drainage, Montreal, QC, Canada, 16–18 September 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, P.; White, R.; Cadden, A. Paste, the future of tailings disposal. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Mining and the Environment, Mataram, Indonesia, 18–19 August 2021; Volume 594. [Google Scholar]

- Melis, L.A. Development of the Disposal Technology Research Component of the National Uranium Tailings Program. In Report 0SQC2-00252, Prepared for The Canada Centre for Mineral and Energy Technology, Energy, Mines and Resources; CANMET: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1985; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Paynter, J.T.; Dodd, J.C. The design, commissioning and operation of the Golden Giant paste backfill plant. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Mineral Processors (Division of the CIM), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 21–23 January 1997; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.J. Model studies on the stability of confined fills. Can. Geotech. J. 1989, 26, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, A.S. (Ed.) Stability of cemented tailings mine backfill. In Computer and Physical Modelling in Geotechnical Engineering, Proceedings of International Symposium on Computer and Physical Modelling in Geotechnical Engineering, Bangkok, Thailand, 3-6 December 1986; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1989; Volume 1, pp. 501–508. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, F.; Archibald, J. Mine backfill, CD-ROM. Can. Inst. Mine Metall. Pet. 1998, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Belem, T.; Benzaazoua, M.; Bussiere, B. Mechanical behaviour of cemented paste backfill. In Proceeding of the 55th Canadian Geotechnical Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–23 October 2000; pp. 575–580. [Google Scholar]

- Benzaazoua, M.; Belem, T.; Bussiere, B. Chemical factors that influence on the performance of mine sulphidic paste backfill. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 52, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belem, T.; Benzaazoua, M. Design and application of underground mine paste backfill technology. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2008, 26, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belem, T.; Benzaazoua, M.; Bussière, B. Utilisation du Remblai en Pâte Comme Support de Terrain. Partie I: De sa fabrication à sa Mise en place Sous Terre. In Symposium International Après-Mines, GISOS; GISOS, Ed.; GISOS: Nancy, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L.; Ren, Z.Z.; Huo, Z.K.; Zheng, Y.C.; Tian, X.P.; Zhang, K.F.; Zhao, G.F. Properties and hydration characteristics of mine cemented paste backfill material containing secondary smelting water-granulated nickel slag. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 4961–4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.G. Fill Technology in Underground Metalliferous Mines; Australian Mineral Foundation: Glenside, Australia, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, E.; Archibald, J.F.; Dirige, A.P.E. Economics and Perspectives of Underground Backfill Practices in Canadian Mining. In 106th Annual General Meeting of the Canadian Institute of Mining; Metallurgy and Petroleum: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C.C.; Vickery, J.D.; Backer, R.R. Transport of total tailings paste backfill: Results of full-scale pipe test loop. Rep. Investig. 1996, 9573, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Kalonji, K.; Mbonimpa, M.; Belem, T.; Ouellet, S.; Gelinas, L.P. Backfilling in the Permafrost: Predicting Pressure Loss and Temperature Distribution Along the Paste Backfill Pipeline System. In Paste 2026, Proceeding of the 25th International Conference on Paste, Thickened and Filtered Tailings Paste 2023, 29 April–6 May 2023; Fairmont Banff Springs Hotel: Banff, AB, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kalonji, K.; Mbonimpa, M.; Belem, T.; Ouellet, S.; Gélinas, L.P. Numerical Procedure for Scaling up Pressure Loss from Mini Flow Loop Tests. In Paste 2026, Proceeding of the 25th International Conference on Paste, Thickened and Filtered Tailings Paste 2023, 29 April–6 May 2023; Fairmont Banff Springs Hotel: Banff, AB, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.; Chen, Q.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yaseen, Z.M. Pressure drops of fresh cemented paste backfills through coupled test loop experiments and machine learning techniques. Powder Technol. 2020, 361, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.L.; Hou, C.; Li, L.; Du, J.F.; Yan, B.X. Experimental investigation on flow properties of cemented paste backfill through L-pipe and loop-pipe tests. J. Cent. South Univ. 2021, 28, 2830–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Huo, H.; Li, J.; Ni, W. Slurry Transportation Characteristics of Potash Mine Cemented Paste Backfills via Loop Test Processing. Processes 2024, 12, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landriault, D.A. Paste backfill Mix Design for Canadian Underground Hard Rock Mining. In The 97th Annual General Meeting of the CIM; Rock Mechanics and Strata Control Session: Halifax, NS, Canada, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Benzaazoua, M.; Fall, M.; Ouellet, S. Étude pluridisciplinaire visant à mettre au point un outil expert pour la prédiction du comportement des remblais en pâte. In Rapport n° R-390; IRSST: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brackebusch, F.W. Basics of Paste Backfill Systems. Min. Eng. 1994, 46, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Benzaazoua, M.; Belem, T.; Ouellet, S.; Fall, M. Utilisation du Remblai en Pâte Comme Support de Terrain. Partie II: Comportement a Court, a Moyen et a Long Terme. In Apres-Mines 2003; GISOS, Ed.; GISOS: Nancy, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, A.; Yanful, E.K. A Review of binders used in Cemented Paste Tailings for Underground and Surface Disposal Practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 131, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landriault, D. Keynote Address: They said “It will never work”–23 Years of Paste Backfill 1981–2006. In Paste 2006, Proceedings of the Ninth International Seminar on Paste and Thickened Tailings, Paste 2006, Limerick, Ireland, 3–7 April 2006; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Crawley, Australia, 2006; pp. 277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Amri, M.; Belem, T.; Mrad, H.; Gélinas, L.P.; Masmoudi, F. Prediction of the Mechanical Properties of Cemented Paste Backfill Using Artificial Intelligence Approaches. In Paste 2023, Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Paste, Thickened and Filtered Tailings, 29 April 2023; University of Alberta: Edmonton, Canada; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Perth, Australia, 2023; pp. 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Benzaazoua, M.; Bussière, B.; Demers, I.; Aubertin, M.; Fried, É.; Blier, A. Integrated mine tailings management by combining environmental desulphurization and cemented paste backfill: Application to mine Doyon, Quebec, Canada. Miner. Eng. 2008, 21, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethier, M.P.; Bussière, B.; Aubertin, M.; Maqsoud, A.; Demers, I.; Broda, S. In situ evaluation of performance of reclamation measures implemented on abandoned reactive tailings disposal site. Can. Geotech. J. 2018, 55, 1742–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouffa, N. Solubilité de Différents Minéraux Aluminosilicatés en Vue de Leur Contribution à la Géopolymérisation dans les Remblais Miniers en Pâte. Master’s Thesis, École Polytechnique, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen, S.W.; Rueslåtten, H.G. Feldspar and Mica. Key Minerals for Fine Aggregate Quality. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 1980, 22, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mshali, M.R.; Visser, A.T. Influence of Mica on Compactability and Moisture Content of Cement–Treated Weathered Granite Gravel. In Proceedings of the 33rd Southern African Transport Conference SATC 2014, Pretoria, South Africa, 7–10 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshkbijari, R.K.; Samimi, M.F.; Mohammadi, F.; Talebitaher, P. Effects of Mica and Feldspar as partial cement replacement on the rheological, mechanical and thermal durability of self-compacting mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.L.; Han, C.Q.; Chen, M.L.; Fan, G.; Zhou, J.W. Improving mechanical properties of manufactured sand concrete with high biotite content: Application of magnetic separation process and equipment optimization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 350, 128–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Wang, C.; Tian, Y.; Xie, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, X. Unraveling polycarboxylate superplasticizer (PCE) compatibility in muscovite-blended cement paste through aggregation mechanisms. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoslovich, E.W. The structure of muscovite, KAl2(Si3Al)O10(OH)2. Acta Crystallogr. 1960, 13, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebau, F. Structural chemistry of silicates: Structure, bonding, and classification; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 13, pp. 919–932. [Google Scholar]

- Van Olphen, H. An Introduction to Clay Colloid Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Carty, W.M. The colloidal nature of kaolinite. Mater. Equip./Whitewares Ceram. Eng. Sci. Proc. 2001, 22, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Luckham, P.F.; Rossi, S. The colloidal and rheological properties of bentonite suspensions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1999, 82, 43–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, B.; Melton, I.E. Particle interactions in aqueous kaolinite suspensions: I. Effect of pH and electrolyte upon the mode of particle interaction in homoionic sodium kaolinite suspensions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1977, 60, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdukova, E.; Bradshaw, D.J.; Laskowski, J.S. Effect of CMC and pH on the rheology of suspensions of isotropic and anisotropic minerals. Can. Metall. Q. 2007, 46, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdukova, E.; Becker, M.; Ndlovu, B.; Mokgethi, B.; Deglon, D.A. Relationship Between Slurry Rheology and Its Mineralogical Content. In 24th Int. Minerals Processing Congress; China Scientific Book Service Co. Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2008; pp. 2169–2178. [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, P.; Revil, A. A mechanistic model for the spectral induced polarization of clay materials. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, B.N.; Becker, M.; Forbes, E.; Deglon, D.; Franzidis, J.P. The influence of phyllosilicate mineralogy on the rheology of mineral slurries. Miner. Eng. 2011, 24, 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, B.N.; Forbes, E.; Becker, M.; Deglon, D.A.; Franzidis, J.P.; Laskowski, J.S. The effects of chrysotile mineralogical properties on the rheology of chrysotile suspensions. Miner. Eng. 2011, 24, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landriault, D.; Welch, D.; Morrison, D. Mine tailings disposal as a paste backfill for underground mine backfill and surface waste deposition; Short Course; Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration: Englewood, CO, USA, 1996; pp. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of gases in multimolecular layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahns, R.H.; Lancaster, F.W. Physical Characteristics of Commercial Sheet Muscovite in the Southeastern United States. Geol. Surv. Prof. Pap. 1950, 225, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Young, R.A. The Rietveld Method; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dikonda, R.K.; Mbonimpa, M.; Belem, T. Specific Mixing Energy of Cemented Paste Backfill, Part I: Laboratory Determination and Influence on the Consistency. Minerals 2021, 11, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikonda, R.K.; Mbonimpa, M.; Belem, T. Specific Mixing Energy of Cemented Paste Backfill, Part II: Influence on the Rheological and Mechanical Properties and Practical Applications. Minerals 2021, 11, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C143/C143M-15a; Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic Cement Concrete. American Society of Testing Material International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Nguyen, D.Q.; Boger, D.V. Direct yield stress measurement with the vane method. J. Rheol. 1985, 29, 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, H.A.; Nguyen, Q.D. Rotating vane rheometry—A review. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2001, 98, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, M.; James, D.F.; Klein, K.A. Flow behaviour of tailings paste for surface disposal. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2005, 77, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Fall, M.; Cai, S.J. Coupling temperature, cement hydration and rheological behaviour of fresh cemented paste backfill. Miner. Eng. 2013, 42, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, D.; Yahia, A.; Mbonimpa, M.; Belem, T. Effects of superplasticizer on rheological properties of cemented paste backfills. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2017, 161, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, D.; Mbonimpa, M.; Yahia, A.; Belem, T. Assessment of rheological parameters of high density cemented paste backfill mixtures incorporating superplasticizers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, S.; Deb, D.; Sreenivas, T. Variability in rheology of cemented paste backfill with hydration age, binder and superplasticizer dosages. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 2211–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshani, A.; Fall, M. Rheological properties of cemented paste backfill with nano-silica: Link to curing temperature. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 114, 103–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschel, W.H.; Bulkley, R. Konsistenzmessungen von Gummi Benzolloesungen. Kolloid-Z. 1926, 39, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.M. Rheology of Non-Newtonian Fluids. A New Flow Equation for Pseudo-plastic Systems. J. Colloid Sci. 1965, 20, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, D.; Mbonimpa, M.; Yahia, A.; Belem, T. Investigations of the Performance of Superplasticizers on Rheological Properties of Highly Viscous Cemented Paste Backfill Mixtures. Ph.D. Thesis, UQAT, Rouyn-Noranda, QC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cyr, M.; Legrand, C.; Mouret, M. Study of the shear thickening effect of superplasticizers on the rheological behaviour of cement pastes containing or not mineral additives. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahia, A.; Perrot, A. Measuring Procedures. In Measuring Rheological Properties of Cement-Based Materials; Sonebi, M., Feys, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2024; Volume 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamee, P.K.; Aggarwal, N. Explicit equations for laminar flow of Herschel–Bulkley fluids. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2011, 89, 1426–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatankhah, A.R. Analytical solutions for Bingham plastic fluids in laminar regime. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2011, 78, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullum, L.; Fourie, A.B.; Jewell, R.J. Pipelining Tailings, Pastes and Backfill. In Proceedings of the 10th International Seminar on Paste and Thickened Tailings, Perth, Australia, 13–15 March 2007; Volume 1315, pp. 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hallbom, D.J. Pipe Flow of Homogeneous Slurry. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Grain-Size Parameters | Tailings RL | Tailings RW | Muscovite M7L | Muscovite M4W |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D90 (µm) | 94.4 | 125 | 97.5 | 130 |

| D60 (µm) | 26.6 | 37.8 | 27.7 | 45.3 |

| D50 (µm) | 18.9 | 27.4 | 18.2 | 30.1 |

| D30 (µm) | 9.4 | 14.5 | 7.0 | 11.3 |

| D10 (µm) | 3.3 | 6.9 | 2.0 | 2.8 |

| CU (-) | 8.2 | 5.7 | 13.9 | 16.4 |

| CC (-) | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| P20µm (%) | 51.7 | 39.8 | 52.3 | 40.9 |

| P80µm (%) | 87 | 80 | 85 | 75 |

| Minerals | M7L M4W | RL | RW | RL + M7L (α = 13%) | RW + M4W (α ≈ 13%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz | 0 | 51.5 | 45.8 | 45.5 | 40.1 |

| Muscovite * | 100 | 15.1 | 14.3 | 25.1 | 24.3 |

| Pyrite | 0 | 12.6 | 2.6 | 11.1 | 2.3 |

| Clinochlore * | 0 | 6.2 | 5 | 5.5 | 4.4 |

| Gypsum | 0 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.7 | 0.9 |

| Albite | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0.0 | 16.6 |

| Ankerite | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Augite | 0 | 10.4 | 10 | 9.2 | 8.8 |

| Calcite | 0 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| * Phyllosilicates | 100 | 21.3 | 19.3 | 31.3 | 29.3 |

| Muscovite Content X | Target Cw (%) | Conducted Tests | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RW | RL | ||

| Xi = 14% ≤ X ≤ Xf = 24% | 70, 72, 74 | - |

|

| Xi = 15% ≤ X ≤ Xf = 25% | - | 69, 71, 73 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Menasria, H.G.; Mbonimpa, M.; Belem, T.; Maqsoud, A. Consistency and Rheological Properties of Cemented Paste Backfills Prepared with Tailings with Varying Free Muscovite Content. Mining 2025, 5, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5010010

Menasria HG, Mbonimpa M, Belem T, Maqsoud A. Consistency and Rheological Properties of Cemented Paste Backfills Prepared with Tailings with Varying Free Muscovite Content. Mining. 2025; 5(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenasria, Hadj Ghani, Mamert Mbonimpa, Tikou Belem, and Abdelkabir Maqsoud. 2025. "Consistency and Rheological Properties of Cemented Paste Backfills Prepared with Tailings with Varying Free Muscovite Content" Mining 5, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5010010

APA StyleMenasria, H. G., Mbonimpa, M., Belem, T., & Maqsoud, A. (2025). Consistency and Rheological Properties of Cemented Paste Backfills Prepared with Tailings with Varying Free Muscovite Content. Mining, 5(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5010010