Assessment of the Family Context in Adolescence: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

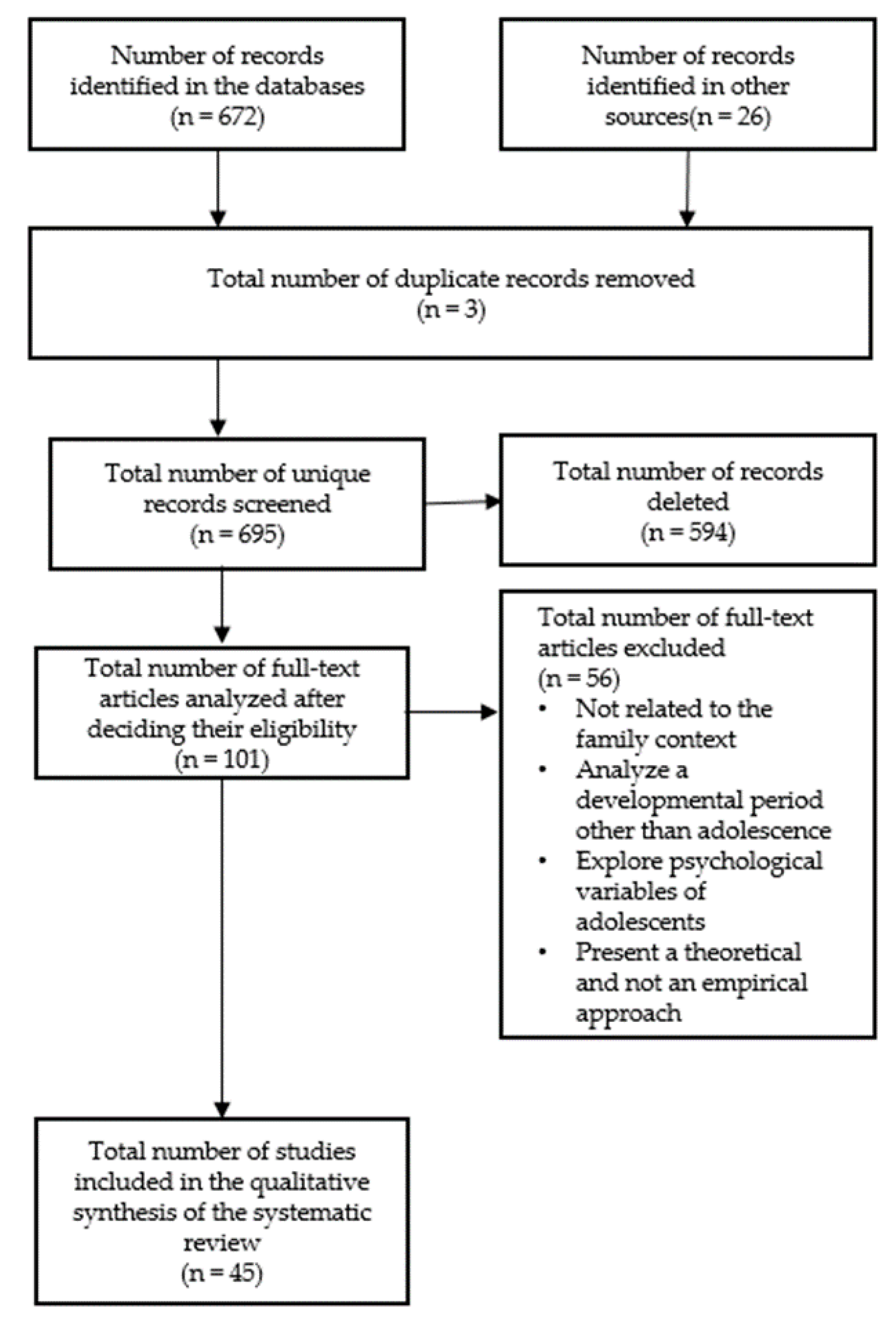

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Databases

2.2. Search Formulas

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Family Dynamics

3.1.1. Parental Competence and Resilience Scale for Mothers and Fathers in Contexts of Psychosocial Risk

3.1.2. Scale for the Evaluation of Parental Style (EEP)

3.1.3. Social Support Scale (PSS)

3.1.4. Free Time Activities Scale

3.2. Family Functioning

3.2.1. Family Assessment Resources (FAD)

3.2.2. Family Cohesion and Adaptability Assessment Scales (FACES)

3.2.3. Family Communication Scale (FCS)

3.2.4. Family Satisfaction Scale (FSS)

3.2.5. Family Satisfaction Scale by Adjectives (ESFA)

3.3. Family Setting

3.3.1. Parental Stress Index (PSI)

3.3.2. Scales “When We Disagree” (WWD)

3.3.3. Family Health Scale

3.3.4. Protective Factors Survey (PFS)

3.3.5. Scale of Adaptation, Participation, Gain, Affection and Resources (APGAR)

3.3.6. Index of Family Functioning and Change (SCORE)

3.4. Family Relationships

3.4.1. Social Systems Assessment Scale (EVOS)

3.4.2. Family Integration Inventory (Arias et al., 2013)

3.4.3. Social Climate Scales in the Family (FES)

3.4.4. Self-Questionnaire of Internal Models of Adult Attachment Relationships (CaMir)

3.4.5. Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cánovas, P.; Sahuqillo, P. Familias y Menores. Retos y Propuestas Pedagógicas; Tirant Humanidades: Valencia, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Musitu, G.; Román, J.M.; Gutiérrez, M. Educación Familiar y Socialización de los Hijos; Idea Books: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nardone, G.; Gianonotti, E.; Rocchi, R. Modelos de Familia. Conocer y Resolver los Problemas Entre Padres e Hijos; Herder: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, M.F.V.; Loving, R.D.; Lagunes, L.I.R.; Peñaloza, J.L.; del Castillo, C.C. Construcción de una escala de actividades de tiempo libre en padres de familia mexicanos. Psicol. Iberoam. 2018, 26, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oropesa, F.; Moreno, C.; Pérez, P.; Muñoz-Tinoco, V. Routine leisure activities: Opportunity and risk in adolescence/Rutinas de tiempo libre: Oportunidad y riesgo en la adolescencia. Cult. Educ. 2014, 26, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oropesa, N.F.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Martos, A.; Simón, M.M.; Barragán, A.B.; Soriano, J.G.; Gázquez, J.J. Actividades de tiempo libre y vivencia subjetiva en la adolescencia. In Salud y Cuidados Durante el Desarrollo; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C., Gázquez, J.J., Molero, M.M., Martos, Á., Simón, M.M., Barragán, A.B., Oropesa, N.F., Eds.; Asociación Universitaria de Educación y Psicología (ASUNIVEP): Almeria, Spain, 2019; Volume 3, pp. 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948. Available online: http://www.verklaringwarenatuur.org/Downloads_files/Universal%20Declaration%20of%20Human%20Rights.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989. Available online: http://wunrn.org/reference/pdf/Convention_Rights_Child.PDF (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Ullmann, H.; Maldonado Valera, C.; Rico, M.N. La Evolución de las Estructuras Familiares en América Latina, 1990–2010: Los Retos de la Pobreza, la Vulnerabilidad y el Cuidado; CEPAL-UNICEF: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, E.; Fuentes, M.C.; Garcia, F.; Lila, M. Perceived neighborhood violence, parenting styles, and developmental outcomes among Spanish adolescents. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 40, 1004–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Iglesias, A.; Moreno, C.; García-Moya, I.; Ramos, P. How can parents obtain knowledge about their adolescent children? Infanc. Aprendiz. 2013, 36, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stattin, H.; Kerr, M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 1072–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, J.M. Bases to build a positive communication in the family. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2011, 9, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Gázquez, J.J.; Oropesa, N.F.; Simón, M.M.; Saracostti, M. Parenting Practices, Life Satisfaction, and the Role of Self-Esteem in Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baumrind, D. Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Dev. 1966, 3, 887–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, E.; Martin, J.A. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In Handbook of Child Psychology. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development; Hetherington, E.M., Mussen, P.H., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 4, pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Musitu, G.; Estevez, E.; Jimenez, T. Relaciones Familiares. Fundación Familia; Editorial Cinca: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- García, F.; Gracia, E. What is the optimum parental socialisation style in Spain? A study with children and adolescents aged 10–14 years. Infanc. Aprendiz. 2010, 33, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torío, S.; Peña, J.V.; Inda, M. Estilos de educación familiar. Psicothema 2008, 20, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, M.; Alvarado, F.; Oleas, C. Evaluación de los estilos educativos familiares en la ciudad de Cuenca. Maskana 2015, 6, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, M.J.; Amorós, P.; Arranz, E.; Hidalgo, M.V.; Máiquez, M.L.; Martín, J.C.; Martínez, R.; Ochaita, E. Guía de Buenas Prácticas en Parentalidad Positiva. Un Recurso Para Apoyar la Práctica Profesional con Familias; Federación Española de Municipios y Provincias (FEMP): Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barudy, J. Familiaridad y competencias: El desafio de ser padres. In Los Buenos Tratos a la Infancia. Parentalidad, Apego y Resiliencia; Barudy, J., Dantagnan, M., Eds.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2005; pp. 77–125. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, J.; Shaver, P.R. Handbook of attachment. In Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Vereijken, C.H.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Riksen-Walraven, J.M. Assessing attachment security with the attachment Q sort: Meta-analytic evidence for the validity of the observer AQS. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 1188–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Slade, A. Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2005, 7, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meanley, S.; Flores, D.D.; Listerud, L.; Chang, C.J.; Feinstein, B.A.; Watson, R.J. The interplay of familial warmth and LGBTQ+ specific family rejection on LGBTQ+ adolescents’ self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 2021, 93, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigo, M.J.; Máiquez, M.L.; Martín, J.C.; Byrne, S. Preservación Familiar: Un Enfoque Positivo Para la Intervención con Familias; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo, M.J.; Martín, J.C.; Cabrera, E.; Máiquez, M. Las competencias parentales en contextos de riesgo psicosocial. Psychosoc. Interv. 2009, 18, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-García, D.; García, T.; Barreiro-Collazo, A.; Dobarro, A.; Antúnez, Á. Parenting style dimensions as predictors of adolescent antisocial behavior. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Domínguez, A.C.; Contreras, C. Psychometrics Quality Evaluation of the Mexican versión of PSS-Fa & PSS-Fr using a Rasch Model. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval.-E Aval. Psicol. 2010, 1, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, J.C.; Cabrera, E.; León, J.; Rodrigo, M.J. The Parental Competence and Resilience Scale for mother and fathers in at-risk psychosocial contexts. Ann. Psychol. 2013, 29, 886–896. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, A.; Parra, A.; Sánchez-Queija, I.; López, F. Maternal and paternal parenting styles: Assessment and relationship with adolescent adjustment. Ann. Psychol. 2007, 23, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Procidano, M.E.; Heller, K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1983, 11, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraca, J.; López-Yarto, L. ESFA. Escala de Satisfacción Familiar por Adjetivos; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, N.B.; Baldwin, L.M.; Bishop, D.S. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 1983, 9, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cracco, C.; Costa-Ball, C.D. Psychometric properties of the family communication scale. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval.-E Aval. Psicol. 2019, 2, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, L.; Lorence, B.; Hidalgo, V.; Menéndez, S. Factor analysis of FACES (Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales) with families at psychosocial risk. Univ. Psychol. 2017, 16, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marsac, M.L.; Alderfer, M.A. Psychometric properties of the FACES-IV in a pediatric oncology population. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011, 36, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Pampliega, A.; Merino, L.; Iriarte, L.; Olson, D.H. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale IV. Psicothema 2017, 29, 414–420. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.H. FACES IV and the circumplex model: Validation study. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2011, 37, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.; Barnes, H. Family Communication Scale; Life Innovations, Inc.: Minnesota, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.H.; Bell, R.; Portner, J. Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales (Unpublished Manuscript); Family Social Science Department, University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.; Gorall, D.; Tiesel, J. FACES IV Package. Administration Manual; Life Innovations, Inc.: Minnesota, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M.G.; Teixeira, R. Portuguese validation of FACES IV in adult children caregivers facing parental cancer. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2013, 35, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olson, D.H.; Wilson, M. Family satisfaction. In Family Inventories: Inventories Used in a National Survey of Families across the Family Life Cycle; Olson, D.H., McCubbin, H.I., Barnes, H., Larsen, A., Muxen, M., Wilson, M., Eds.; University of Minnesota: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1982; pp. 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Quintanilla, G.T.; Sotomayor, M.D.; Hernández, O.M.; Peralta, P.C.; Domingo, M.M.; Roque, A.H.; Coqui, M.L. Escala de Satisfacción Familiar por Adjetivos (ESFA) en escolares y adolescentes mexicanos: Datos normativos. Salud Ment. 2013, 36, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, V.; Barreyro, J.P.; Maglio, A.L. Family Functioning Evaluation Scale FACES III: Model of two or three factors? Escr. Psicol. 2010, 3, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsamparli, A.; Petmeza, I.; McCarthy, G.; Adamis, D. The Greek version of the mcmaster family assessment device. PsyCh J. 2018, 7, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Zegarra, D.; Copez-Lonzoy, A.; Paz-Jesús, A.; Costa-Ball, C.D. Validity and Reliability of the Family Satisfaction Scale in University Students of Lima, Peru. Actual. Psicol. 2017, 31, 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, R.R. Parenting Stress Index (Short Form); Psychological Assessment Resource: Odessa, Ukraine, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cicognani, E.; Zani, B. An instrument for measuring parents’ perceptions of conflict style with adolescents: The “When We Disagree” scales. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 7, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad-Hiebner, A.; Schoemann, A.M.; Counts, J.M.; Chang, K. The development and validation of the Spanish adaptation of the Protective Factors Survey. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 52, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counts, J.M.; Buffington, E.S.; Chang-Rios, K.; Rasmussen, H.N.; Preacher, K.J. The development and validation of the protective factors survey: A self-report measure of protective factors against child maltreatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2010, 34, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Cárdenas, S.; Tirado-Amador, L.; Simancas-Pallares, M. Construct validity and reliability of the family APGAR in adult dental patients from Cartagena, Colombia. Rev. Univ. Ind. Santander Salud 2017, 49, 541–548. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Herrero, A.; Brito, A.; López, J.A.; Pérez-López, J.; Martínez-Fuentes, M.T. Factor structure and internal consistency of the Spanish version of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form. Psicothema 2010, 22, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, J.S.; Lima, M.; Jiménez, N.; Domínguez, I. Consistencia interna y validez de un cuestionario para medir la autopercepción del estado de salud familiar. Rev. Esp. Salud Publ. 2012, 86, 509–521. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hanrahan, K.; Daly White, M.; Carr, A.; Cahill, P.; Keenleyside, M.; Fitzhenry, M.; Harte, E.; Hayes, J.; Noonan, H.; o’Shea, H.; et al. Validation of 28 and 15 item versions of the SCORE family assessment questionnaire with adult mental health service users. J. Fam. Ther. 2017, 39, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivas, G.; Pereira, R. Validación de una escala de evaluación familiar adaptación del SCORE-15 con normas en español. J. Span. Fed. Fam. Ther. Assoc. 2016, 63, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Smilkstein, G.; Ashworth, C.; Montano, D. Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. J. Fam. Prac. 1982, 15, 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, P.; Bland, J.; Janes, E.; Lask, J. Developing an indicator of family function and a practicable outcome measure for systemic family and couple therapy: The SCORE. J. Fam. Ther. 2010, 32, 232–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilaça, M.; Relvas, A.P.; Stratton, P. A Portuguese translation of the Systemic Clinical Outcome and Routine Evaluation (SCORE): The psychometric properties of the 15-and 28-item versions. J. Fam. Ther. 2018, 40, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetterqvist, M.; Hånell, H.E.; Wadsby, M.; Cocozza, M.; Gustafsson, P.A. Validation of the Systemic Clinical Outcome and Routine Evaluation (SCORE-15) self-report questionnaire: Index of family functioning and change in Swedish families. J. Fam. Ther. 2020, 42, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguilar-Raab, C.; Grevenstein, D.; Schweitzer, J. Measuring social relationships in different social systems: The construction and validation of the evaluation of social systems (EVOS) scale. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, W.L.; Castro, R.; Dominguez, S.; Masías, M.A.; Canales, F.; Castilla, S.; Castilla, S. Construcción de un inventario de integración familiar. Av. Psicol. 2013, 2, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, W.; Castro, R.; Rivera, R.; Ceballos, K. Exploratory factor analysis of the Family Integration Inventory in a sample of workers from Arequipa City. Cienc. Psicol. 2019, 13, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, Y.; Vallejo, V.J.; Villada, J.A.; Zambrano, R. Parental Bonding Instrument’s (PBI) psychometric properties of population from Medellín, Colombia. Pensam. Psicol. 2010, 11, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Grevenstein, D.; Schweitzer, J.; Aguilar-Raab, C. How children and adolescents evaluate their families: Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Evaluation of Social Systems (EVOS) scale. J. Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, L.; Fang, F. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Parental Bonding Instrument. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayorga, M.N.; Koroleff, P.T. Reliability and Validity of Attachment Cognitions: CaMir Q Sort, with a Peruvian Sample. Pensam. Psicol. 2013, 11, 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Moos, R.; Moos, B.; Tricket, J. Manual de la Escala de Clima Social Familiar (FES); TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, G.; Tupling, H.; Brown, L.B. A Parental Bonding Instrument. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1979, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrehumbert, B.; Karmaniola, A.; Sieye, A.; Meister, C.; Miljkovitch, R.; Halfon, O. Les Modèles de relations: Devèloppement d’un auto-questionnarie d’attachement pour adultes. Psychiatr. L’Enfant 1996, 1, 161–206. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, Á.A.; Carlos, E.A.; Vera, J.Á.; Montoya, G. Propiedades psicométricas de un instrumento para medir las relaciones familiares en adolescentes intelectualmente sobresalientes. Pensam. Psicol. 2012, 10, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Da Siva, R.; Batista, M.; Astrês, M.; Gouveia, M.; Freitas, G. Translation and cultural adaptation of death attitude profile Revised (DAP-R) for use in Brazil. Texto Contexto-Enferm. 2019, 28, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. PRISMA declaration: A proposal to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Med. Clin. 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Instrument/Country | Authors/Year | Dimensions and Main Results | Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of the Studies on Family Dynamics | |||

| Parental Competency and Resilience Scale for mothers and fathers in contexts of psychosocial risk (Spain) |

|

| |

| Scale for the Evaluation of Parental Style (Spain) |

|

|

|

| Social Support Scale (USA) |

|

|

|

| Activity Scale of Free Time (Mexico) |

|

| |

| Characteristics of the studies on family functioning | |||

| Family Assessment Resources (USA) |

|

|

|

| Family Cohesion and Adaptability Assessment Scales (USA) |

|

|

|

| Family Communication Scale (USA) |

|

|

|

| Family Satisfaction Scale(USA) |

|

|

|

| Family Satisfaction Scale by Adjectives (Spain) |

|

|

|

| Characteristics of the studies on family adjustment | |||

| Parental Stress Index (USA) |

|

|

|

| Scales “When we disagree” (Italy) |

|

| |

| Family Health Scale (Spain) |

|

| |

| Protective Factors Survey (Spain) |

|

|

|

| Family Adaptation, Participation, Gain, Affection and Resources Scale (USA) |

|

|

|

| Index of Family Functioning and Change (UK.) |

|

|

|

| Characteristics of the studies on family relationships | |||

| Social Systems Assessment Scal (Germany) |

|

|

|

| Social Climate Scales in the Family (Peru) |

|

|

|

| Family Integration Inventory (USA) |

|

|

|

| Self-Questionnaire of Internal Models of Adult Attachment Relationships (France) |

|

|

|

| Parental Attachment Instrument (Australia) |

|

| |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oropesa Ruiz, N.F. Assessment of the Family Context in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Adolescents 2022, 2, 53-72. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2010007

Oropesa Ruiz NF. Assessment of the Family Context in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Adolescents. 2022; 2(1):53-72. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleOropesa Ruiz, Nieves Fátima. 2022. "Assessment of the Family Context in Adolescence: A Systematic Review" Adolescents 2, no. 1: 53-72. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2010007

APA StyleOropesa Ruiz, N. F. (2022). Assessment of the Family Context in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Adolescents, 2(1), 53-72. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2010007