Abstract

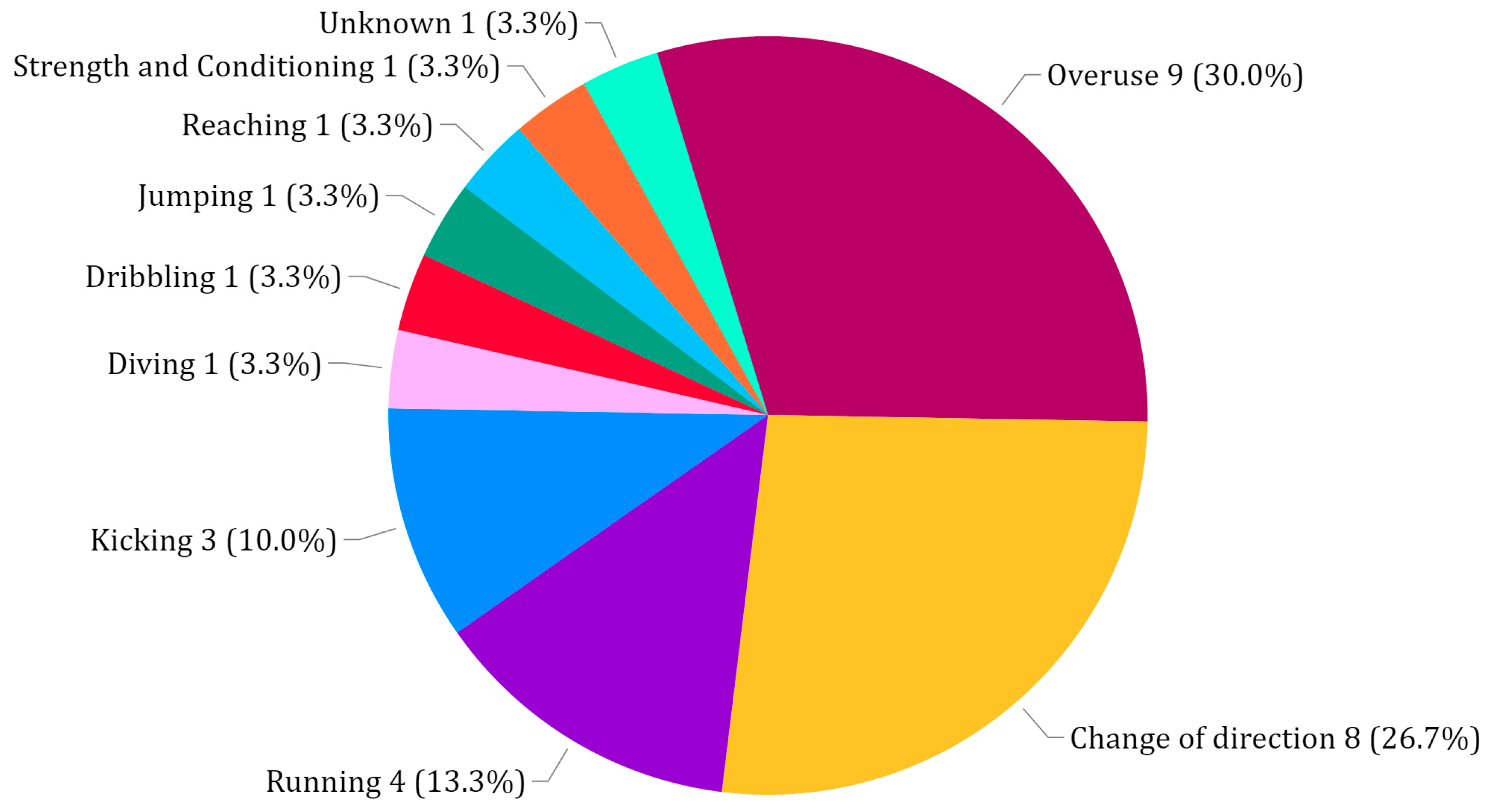

Adductor strains are prevalent injuries in professional soccer. The purpose of this study is to identify further evidence of characteristics associated with adductor injury. MLS and other worldwide leagues have differing styles of play warranting further investigation of injury mechanisms. A descriptive cohort study was conducted with a single professional team in the MLS. Injury data was collected between the 2016 to 2022 seasons to characterize adductor injury. Player position type, age, previous injury, and mechanism(s) of injury (MOI) were assessed to understand the injured population. Generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were utilized to assess the odds of future injury among the injured and non-injured populations. Adductor strains (n = 30) made up 15.5% of all soft-tissue, lower extremity injuries (n = 194) in a single MLS cohort. These injuries were the second most common defined soft-tissue, non-contact injury after hamstring strains (26.4%) and before quadricep strains (11.9%). Among the position types, 28% of defenders, 25% of goalkeepers, 21.4% of forwards, and 20.5% of midfielders experienced at least one adductor strain. The MOI most responsible for these injuries were overuse (30%), change of direction (26.7%), running (13.3%), and kicking (10%). Athletes with previous adductor injury had 167.2 times the odds of adductor injury in a future half-season compared to non-injured athletes. The findings from this study provide further descriptive evidence of player position types and mechanisms related to adductor strain. Insights into the nature of injury within an MLS team and support of previous evidence shows the prevalence of adductor injuries in elite soccer players.

1. Introduction

Adductor injuries are among the most common injuries that occur in soccer and have been found to account for up to 23% of all muscle injuries among elite soccer players [1,2,3,4,5,6]. These types of injuries have been found to take a median of 14 to 22 days away from play but depending on the grade of the strain can result in missing an entire season [5,7]. This negatively impacts an athlete’s playing exposure and career longevity as prior injury has been found to increase the risk of getting an adductor injury in the future [7]. An adductor strain is defined as an “injury to the muscle-tendon unit that produces pain on palpation of the adductor muscle or tendons or its insertion on the pubic bone with or without pain during resisted adduction [8,9]”. As soccer is the most popular sport in the world [10,11], such injuries have the potential to impact a large population and thus should be a concentration for research in injury mitigation.

All over the world, soccer, or the equivalent world term football, is played from a recreational to professional level. Regardless of the level of play, similar movement patterns occur that can expose someone to lower extremity injury. The etiology and mechanisms of groin injuries, specifically adductor strain, have only been investigated in a few professional soccer populations. Serner et al. utilized video to determine the most common mechanisms of injury that lead to acute adductor strains in elite male football players. It was found that eccentric action, or lengthening of the muscle during contraction, is a common mechanism of injury and tends to occur during kicking, change of direction, jumping, and reaching movements [12,13]. Another study looked at adductor magnus injury mechanisms among a group of 11 high-level athletes between the ages of 18 to 36 years who were involved in competition-based soccer. They found that the majority of injuries occurred when there was both flexion and internal rotation of the hip paired with knee extension [14]. Further research identifying the mechanisms associated with adductor injury and who may experience these movement patterns most often in soccer would be beneficial to identify at-risk groups.

The four main position types that comprise a team include forwards, midfielders, defenders, and goalkeepers. Each field position type, excluding goalkeepers, can be broken down into specialized positions, such as center backs, full backs, and defensive midfielders. Every field position tends to experience different running speeds, movement patterns, frequency of contact with the ball or players, strength and conditioning plans, and training protocols [8,15,16,17,18,19,20] which may expose them to different injury types. Thus, it is important to acknowledge that some positions may have a greater likelihood of injury due to the difference in external work required. For example, wide midfielders have been found to have the highest number of accelerations, overall distance traveled, sprinting distance, and high-intensity running in a group of U17 players [15]. Observable differences among the four position types have been reported in the Spanish Premier League and Champions League. It was found that midfielders cover statistically significant greater distances during games as well as greater total distances with the ball compared to the other position types [19]. Due to these observations, midfielders could arguably be exposed to higher load throughout a game, and while this does not necessarily mean they have a higher risk of adductor or lower extremity injury specifically, there is an inherent injury risk related to greater load put on an athlete. While there is evidence that supports specific position types having greater external work than others, further observation is needed to definitively determine whether they are at a higher risk of injury.

Assessment of risk factors in previous longitudinal studies has been limited due to the release of information in professional clubs. The ability to have a full library of all reported injuries within the organization and not just what is reported publicly, enables a comprehensive analysis of injuries and risk factors. We can obtain detailed information about a player’s previous injury history, training protocols, and performance and strength testing continuously throughout each season. The aim of this study is to assess if specific characteristics of a soccer player such as position type, age, and history of previous adductor injury may be related to higher occurrences of adductor injury in a relatively controlled environment. We aim to understand the mechanisms that are related to adductor injury as well. We hypothesize that adductor strains will be one of the most common injury types endured in this population. Furthermore, we hypothesize that midfielders would have the highest incidence of injury due to the workload that they experience throughout their training and game schedules. Finally, we hypothesize that the MOI responsible for those injuries would predominantly be changes of direction, reaching, and kicking due to the stress these movements put on the musculature.

2. Materials and Methods

The data for this study were obtained through approval from the MLS M-Marc committee and a singular corresponding Major League Soccer (MLS) team. The inclusion criteria enveloped any player contracted by the MLS team between January 2016 to December 2022. A total of 86 athletes were contracted to the respective team during this period and all were included in this study. Of these individuals, 57 experienced at least one soft-tissue, non-contact lower extremity injury, and 20 were identified from training logs to have had at least one adductor strain during their time with the team. Descriptive analyses of injured and non-injured players were conducted. This includes assessing player position type, age, history of injury, and mechanism of injury (MOI). MOI was defined as the activity that took place at the time of injury. The MOI was determined by medical practitioners, employed by the team, communicating with the player as well as using video footage, if needed, to target what type of mechanism occurred at the instance of injury. If there was no consensus on the mechanism that occurred, it was categorized as unknown. Potential MOI can include kicking, reaching, running, overuse, change of direction, jumping, dribbling, diving, strength and conditioning events, and unknown. Practitioners assigned overuse as a MOI when a recurring complaint of discomfort resulted in injury with no known trauma. A player’s age was recorded at the time of injury. If an individual was not injured during the season, their age was reported from the beginning of each season. For the sake of this research and due to sample size, we will generalize athletes into the four position types, forwards, midfielders, defenders, and goalkeepers.

An injury was defined as any instance when a player noted an injury to medical staff, even if this did not result in time away from play. We analyzed the players’ history of injury and re-injury, where re-injury was defined as any reoccurrence of the same injury and laterality within their time at the club. All injuries were reported into a logging system by one of three medical staff from 2016 to 2022. Within the injury log, staff indicate when the injury happened, injury type, location, severity of the injury, and the mechanism in which the injury occurred. Additionally, it is noted whether the injury occurred during a game, practice, workout, or an off-duty event. If a player went to a specialist for an injury, the notes from the specialist were included. This information was used to give a more detailed understanding of the injury site and type. For example, the grade of strain and exact strain location through imaging, taken with the specialist, may be added to the injury log. Contact vs. non-contact injuries were also defined where a contact injury is considered if the mechanism in which the injury happened included a collision with a person or object. This does not include collision with a ball during a kicking or passing movement, as this is a fundamental aspect of the game. A non-contact injury would mean there was no contact with a person or object at the time of injury.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize player demographics, positions, injury history, and mechanisms of injury. Generalized linear models (GLMs) utilizing GEEs were used to assess previous injury and position as risk factors for future injury among the cohort. The structure of the working correlation matrix was set as a first-order autoregression. This flexible class of models seeks to model population averages and is capable of handling both non-normal and longitudinal data, making it a highly suitable choice for our investigation. For this particular analysis, we assumed that individuals played the same position in subsequent half-seasons; we also controlled for player position in our model. This distinction was made to only compare the non-injured and injured individuals within the same season either in the first or last six months of the year.

3. Results

From 2016 to 2022, 86 male players made up the club population. A total of 57 individuals endured a soft-tissue, non-contact lower extremity injury during the time period of this study with 20 athletes experiencing 30 instances of soft-tissue, non-contact adductor strains. The total population ranged in age from 16 to 35 years old, with a mean and standard deviation of 26 ± 4.61; the injured population, including all injury types, ranged in age from 17 to 35 years old, with a mean and standard deviation of 27 ± 4.40; the adductor injury population ranged in age from 19 to 35 years old, with a mean and standard deviation of 27 ± 4.50. Adductor injuries made up 15.5% of all soft-tissue, non-contact lower extremity injuries (n = 194). The most common soft-tissue, non-contact lower extremity injury was hamstring strains (26.4%) and the third most common, after adductor strains, were quadricep strains (11.9%). Of the individuals who sustained a soft-tissue, non-contact adductor injury, 14 had one occurrence of injury during their time with the team, 4 had two injury occurrences, and 2 had three or more injury occurrences. By our definition of reinjury, we had a total of six reinjuries from four individuals. Thus, reinjury accounted for 20% of all adductor injuries. If we control for reinjuries within the same season, we see there were three reinjuries from three individuals. Adductor injuries were more common on their dominant side (54.8%). Of those that had an adductor injury, 70% occurred at practice with the remaining 30% occurring during a game. If we generalize to five practices a week in a ten-month season with 34 official league games, we can then see that an adductor injury occurred at an estimated 10.5% of practices and 26.5% of games respectively.

Among adductor injuries, 28% of defenders, 25% of goalkeepers, 21.4% of forwards, and 20.5% of midfielders had at least one adductor injury during their time with the team (Table 1). While midfielders had the most adductor injuries (n = 13), when we assessed the number of athletes per position type who were injured, we saw they had the lowest percentage of injured individuals of any position. When we assess the incidence of injury in relation to the 30 total adductor injuries, we see 43.3% of these injuries were experienced by midfielders, 33.3% defenders, 13.3% forwards, and 10% goalkeepers. Defenders (40%) and goalkeepers (37.5%) had the greatest incidence rate in this population over seven consecutive seasons, followed by midfielders (33.3%) and forwards (28.6%).

Table 1.

Soft-tissue, non-contact adductor injury distribution across position types from 2016–2022.

The MOI found in the cases of soft-tissue, non-contact adductor injuries can be seen in Figure 1. Overuse, change of direction, running, and kicking accounted for 80% of adductor injury mechanisms. When we break down MOI by position type, we notice the predominant MOI. For example, in forwards, 75% of adductor injury MOI was reported as overuse. Defenders had 40% classified as overuse and 30% as change of direction. Midfielders had 23% as change of direction and another 23% as running. Goalkeepers experienced three injuries in total due to change of direction, kicking, and overuse MOI, respectively. This can give us insight about the conditions in which players in these positions become injured and when a person may be at higher risk of injury. These findings support that change of direction can put nearly all position types at risk of adductor injury. Overuse was a predominant MOI in all position types as well, whereas we can see that running MOI was experienced mostly by midfielders.

Figure 1.

Soft-tissue, non-contact adductor injury mechanisms (n = 30).

From our assessment of adductor injury through the utilization of GEEs, we found that the presence of a previous adductor injury had a strong association with the odds of adductor injury for any following half-season. Specifically, we observed that players with a previous adductor injury were estimated to have 167.2 times the odds of an adductor injury in a future half-season compared to someone with no previous injury (p < 0.01). Position type, season year, and season half were not found to have significant associations with the odds of injury.

4. Discussion

Findings from a single professional soccer team spanning over a seven-year period have given further insight into the incidence and mechanisms of adductor injury in this population. Over 23% of all athletes who were contracted to the professional team experienced a soft-tissue, non-contact adductor injury between January 2016 and December 2022. Adductor injuries were the second-most common soft-tissue, non-contact lower extremity injury experienced in this population exceeded only by hamstring strains and followed by quadriceps strains. A 6-year study of overall MLS injury rates found that the most common injuries were hamstring strains, ankle sprains, and adductor strains [2]. Both our study and the mentioned MLS study [2] defined injury as any injury logged in the database. However, it should be noted that the league study assessed all injuries, not just non-contact soft tissue injuries. In addition, within professional European and Swedish teams, a similar result was found showing the hamstring (37%), adductor (23%), quadriceps (19%), and calf (13%) muscle groups made up 92% of all muscle injuries [21]. From this, we can see our professional team cohort had similar outcomes of injury compared to all around the world. Of the 20 individuals who experienced an adductor injury, 20% of them (n = 4) experienced at least one reinjury during their time with the team, and 15% (n = 3) experienced a reinjury in the same season. This emphasizes the importance of understanding and taking into consideration precautions for this type of injury and return-to-play protocol.

We hypothesized that midfielders would experience the greatest incidence of adductor injuries due to their high workload in terms of distance covered in games. In fact, we conclude that midfielders experience the greatest number of adductor strains compared to other position types and thus the overall highest proportion of total injuries (43.3%). We can see that Forsythe et al. found similar results regarding incidence among different position types. They found midfielders had the greatest number of adductor strain incidences (n = 330) followed by defenders (n = 245), forwards (n = 113), and goalkeepers (n = 52) [2]. However, when we consider these outcomes normalized by the number of players per position, we see from our study that defenders and goalkeepers had the greatest percentage of players affected by these injuries. It should be noted that midfielders and forwards did still have a large percentage of players who endured these injuries as well. As seen here, defenders had the most adductor injuries within their position type. This can elicit questions related to player anthropometrics, injury history, and/or external work done.

Overuse, change of direction, and running made up approximately 70% of the mechanisms of injury for adductor strains, partially confirming our hypothesis. Overuse is the general fatigue of soft tissue over time. Due to the nature of soccer and the number of high-intensity movements during training and games, soccer players can expose themselves to overuse injuries. For starting players in the games, these athletes can play 90 or more minutes of alternating low- to high-intensity activity during a game setting. This is a unique characteristic of soccer, whereas in many other sports, athletes will be substituted at some point throughout the game. We can see from our findings that adductor injuries occurred at an estimated 26.5% in games and only 10.5% in practices. This leads us to believe that in-game environments could elicit a greater risk of injury. Although practice exposure time is consistent between players, exposure time during games is highly varied and should be considered in future studies. Due to overuse being defined broadly by team practitioners as a recurring complaint with no known trauma, clarification of specific overuse mechanisms is needed before training regimens can be altered.

We can also pinpoint how a change of direction, kicking, and/or running mechanism may put an athlete at a higher risk of injury. While these movements can happen in differing planes of motion, there is still the presence of an adduction force working against an abduction force while the muscle is lengthening which has been found to lead to adductor strain [12]. In kicking specifically, it has been found that the adductor longus is at risk of injury between 30 to 45% of the swing phase due to the greatest rate of lengthening and eccentric activation [22]. In our study, only one reaching and one jumping mechanism were recorded for adductor injury.

Furthermore, we found that injured individuals had 167.2 times the odds of a future adductor injury in a following half-season as compared to non-injured individuals. The large magnitude of this effect can likely be attributed to the relatively low baseline odds of a player experiencing an adductor injury in any given half-season. Nevertheless, this finding supports previous literature that has found previous injury history as a well-defined risk factor for subsequent adductor injury [23,24,25,26,27]. Position type, season year, and season half were not found to be significantly associated with increased odds of injury. It is important to note that player laterality was not taken into consideration in this analysis.

Coaches, medical staff, athletes, training schedules, and the environment greatly influence the type of workload and uncontrollable external factors an athlete may experience. While studies spanning across multiple teams lend themselves to greater external factor variability which could help diversify the population, these heterogeneous studies could fail to recognize specificities in training culture and should be considered when conducting any analysis. Injury characterization from a singular group with consistent training personnel and a team environment, as performed in this study, has provided a controlled environment in a chaotic system.

A notable limitation of this study is the size of the cohort included in this analysis. Ideally, we would include more subjects over the period of this study rather than limiting the sample to a single team over the course of seven seasons. Although this can be seen as a limitation, we should also acknowledge that this has led to more consistent training and rehabilitation methods, creating a more controlled group. Within this study, we did not specify the type of adductor strain relating to the grade of strain, specific adductor muscle, and location of the strain. The inclusion of these details in the future could warrant more refined results. Furthermore, we are only considering injury data from the time an athlete was contracted to the MLS top professional team. This means we do not take into consideration any previous medical history prior to them joining the team. Finally, we should acknowledge that inter-practitioner logging can create variability in how an injury is reported. However, the same practitioners logged injury for all seasons included in this study resulting in less variability relative to studies including multiple teams and changing practitioners. Applied research outside of the lab will have inherent uncontrollable external factors, however, we believe this research is an example of a well-controlled cohort active with a real-world professional team tracked over an extended period of time.

Our findings suggest there are certain position types, movement patterns, practice/game environments, side dominance, and previous adductor injury history that can put an athlete at a higher risk of injury. This information can aid sports scientists and practitioners by giving further knowledge surrounding at-risk categories and further discussion on knowledge of these factors can be integrated into monitoring and training. For a holistic view of injury risk for an individual athlete, future analysis will need to incorporate workload experienced in play, supplemented with motion capture technology, to understand which types of positions and movements are most dangerous with regards to adductor injury.

5. Conclusions

For a single MLS team spanning seven seasons, adductor injuries made up 15.5% of all soft-tissue, non-contact lower extremity injuries throughout the seven seasons of competition. It was found that midfielders (43.3%) and forwards (33.3%) had the greatest proportion of total injury thus the greatest incidence of injury, however, when normalizing to the number of players per position type, forwards (28%) and goalkeepers (25%) had the highest percentage of injured players. The most common mechanisms of adductor strain include overuse (30%), change of direction (26.7%), running (13.3%), and kicking (10%). Previous injury was found to be associated with 167.2 times the odds of future injury in a subsequent half-season as compared to a lack of a previous injury. Many studies previously conducted regarding adductor injury in soccer have utilized injury data from multiple teams across various levels of play and found similar results. These findings can give us a better understanding of who may be at higher risk of injury and further evidence to show the predominant mechanisms of adductor injury in a controlled group within the MLS. The scientific community and practitioners can use this information when addressing individuals who may fall into a similar category, indicating that they may have an inherently greater risk of injury.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D., J.H., M.H. and A.P.; methodology, R.D. and B.B.; software, R.D. and B.B.; validation, R.D., J.H., M.H., A.P., C.B.S. and B.B.; formal analysis, R.D. and B.B.; investigation, R.D.; resources, J.H., B.B., A.P., C.B.S. and M.H.; data curation, R.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.D.; writing—review and editing, R.D., J.H., A.P., C.B.S., B.B. and M.H.; visualization, R.D.; supervision, J.H. and M.H.; project administration, R.D. and J.H.; funding acquisition, R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the NSF GRFP and the University of Delaware Mechanical Engineering Helwig Fellowship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

IRB and MLS M-Marc Medical Committee approval was obtained for this research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent and approval were obtained from the MLS M-Marc Medical Committee.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data permissions are needed by the MLS M-Marc Medical committee and are not available for public sharing.

Conflicts of Interest

The author of this paper participated in a fellowship with a professional soccer team to gain greater sport analytic experience during the 2022 season. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MLS | Major League Soccer |

| MOI | Mechanism of injury |

| GEE | Generalized estimating equation |

| GLM | Generalized linear model |

References

- Ekstrand, J.; Hägglund, M.; Waldén, M. Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football: The UEFA injury study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsythe, B.; Knapik, D.M.; Crawford, M.D.; Diaz, C.; Hardin, D.; Gallucci, J.; Silvers-Granelli, H.J.; Mandelbaum, B.R.; Lemak, L.; Putukian, M.; et al. Incidence of Injury for Professional Soccer Players in the United States: A 6-Year Prospective Study of Major League Soccer. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2022, 10, 23259671211055136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harøy, J.; Clarsen, B.; Thorborg, K.; Hölmich, P.; Bahr, R.; Andersen, T.E. Groin Problems in Male Soccer Players Are More Common Than Previously Reported. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 1304–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, J.; Hägglund, M.; Ekstrand, J.; Waldén, M. Hip and groin time-loss injuries decreased slightly but injury burden remained constant in men’s professional football: The 15-year prospective UEFA Elite Club Injury Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 53, bjsports-2017-097796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Hägglund, M.; Waldén, M.; Ekstrand, J. UEFA injury study: A prospective study of hip and groin injuries in professional football over seven consecutive seasons. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 1036–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noya Salces, J.; Gómez-Carmona, P.M.; Moliner-Urdiales, D.; Gracia-Marco, L.; Sillero-Quintana, M. An examination of injuries in Spanish Professional Soccer League. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2014, 54, 765–771. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie-Gagne, O.; Mehta, N.; Patel, S.; Cohn, M.R.; Forlenza, E.; Nwachukwu, B.U.; Forsythe, B. Adductor Muscle Injuries in UEFA Soccer Athletes: A Matched-Cohort Analysis of Injury Rate, Return to Play, and Player Performance from 2000 to 2015. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021, 9, 232596712110230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.A.; Renstrom, P.A. Groin Injuries in Sport. Sports Med. 1999, 28, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.F.; Silvers, H.J.; Gerhardt, M.B.; Nicholas, S.J. Groin Injuries in Sports Medicine. Sports Health Multidiscip. Approach 2010, 2, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, J.; Junge, A.; Graf-Baumann, T.; Peterson, L. Football is the most popular sport worldwide. Am. J. Sports Med. 2004, 32, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fédération Internationale de Football Association. FIFA Big Count 2006: 270 million people active in football. FIFA Commun. Div. Inf. Serv. 2007, 31, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Serner, A.; Mosler, A.B.; Tol, J.L.; Bahr, R.; Weir, A. Mechanisms of acute adductor longus injuries in male football players: A systematic visual video analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 53, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serner, A.; Tol, J.L.; Jomaah, N.; Weir, A.; Whiteley, R.; Thorborg, K.; Robinson, M.; Hölmich, P. Diagnosis of Acute Groin Injuries: A Prospective Study of 110 Athletes. Am. J. Sports Med. 2015, 43, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechó, S.; Balius, R.; Bossy, M.; Valle, X.; Pedret, C.; Ruiz-Cotorro, Á.; Rodas, G. Isolated Adductor Magnus Injuries in Athletes: A Case Series. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2023, 11, 232596712211388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, S.A.; Brenn, T. Activity Profiles by Position in Youth Elite Soccer Players in Official Matches. Sports Med. Int. Open 2019, 3, E19–E24, Erratum in Sports Med. Int. Open 2019, 3, E65. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, I.; Johansen, D.; Figueiredo, P.; Rebelo, A.; Pettersen, S.A. Positional Differences in Peak- and Accumulated- Training Load Relative to Match Load in Elite Football. Sports 2019, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, J.; Sarmento, H.; Clemente, F.M.; Field, A.; Figueiredo, A.J. The Effect of Contextual Variables on Match Performance across Different Playing Positions in Professional Portuguese Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, J.; Polman, R.; O’Donoghue, P. Physical Demands of Different Positions in FA Premier League Soccer. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2007, 6, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Di Salvo, V.; Baron, R.; Tschan, H.; Calderon Montero, F.; Bachl, N.; Pigozzi, F. Performance Characteristics According to Playing Position in Elite Soccer. Int. J. Sports Med. 2007, 28, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.M.; Joyce, S.M.; Herrington, R.T.; Fox, K.B.; Mumaugh, J.E. External Workloads Vary by Position and Game Result in US-based Professional Soccer Players. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2023, 16, 688–699. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand, J.; Hägglund, M.; Waldén, M. Epidemiology of Muscle Injuries in Professional Football (Soccer). Am. J. Sports Med. 2011, 39, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charnock, B.L.; Lewis, C.L.; Garrett, W.E., Jr.; Queen, R.M. Adductor longus mechanics during the maximal effort soccer kick. Sports Biomech. 2009, 8, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, J.; DeBurca, N.; McCreesh, K. Risk factors for groin/hip injuries in field-based sports: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engebretsen, A.H.; Myklebust, G.; Holme, I.; Engebretsen, L.; Bahr, R. Intrinsic Risk Factors for Groin Injuries among Male Soccer Players. Am. J. Sports Med. 2010, 38, 2051–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, S.G.; Hatem, M.; Bharam, S. Acute Adductor Muscle Injury: A Systematic Review on Diagnostic Imaging, Treatment, and Prevention. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 3591–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhout, R.; Tak, I.; van Beijsterveldt, A.M.; Ricken, M.; Weir, A.; Barendrecht, M.; Kerkhoffs, G.; Stubbe, J. Risk Factors for Groin Injury and Groin Symptoms in Elite-Level Soccer Players: A Cohort Study in the Dutch Professional Leagues. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018, 48, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, J.L.; Small, C.; Maffey, L.; Emery, C.A. Risk factors for groin injury in sport: An updated systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).