A Novel Capacitive Model of Radiators for Building Dynamic Simulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Method

2.2. Radiator Model

- Constant fluid properties: fluid properties like specific heat (Cp) and density (ρ) are assumed constant, ignoring their temperature dependence.

- Local Thermal Equilibrium: no significant delays in heat transfer between the fluid and the radiator.

- Neglect of gravitational and kinetic terms: the influence of gravity (buoyancy effects) and kinetic energy changes in the water flow (due to speed variations) are not included in the calculations.

- Steady-state assumption for heat transfer: The heat transfer coefficients (hi and he) and thermal conductivity (k) are constant over time.

- Constant ambient conditions: Room temperature is fixed at 20 °C.

- Enthalpy flow rate: This is the enthalpy of the water flow throughout the radiator:

- 2.

- Heat transfer from water to radiator: This is the heat transfer rate from the water node, assumed as the average between the inlet and outlet, and the radiator node:

- 3.

- Heat transfer from radiator to room: This term represents the heat transferred from the radiator to the thermal zone:

3. Results

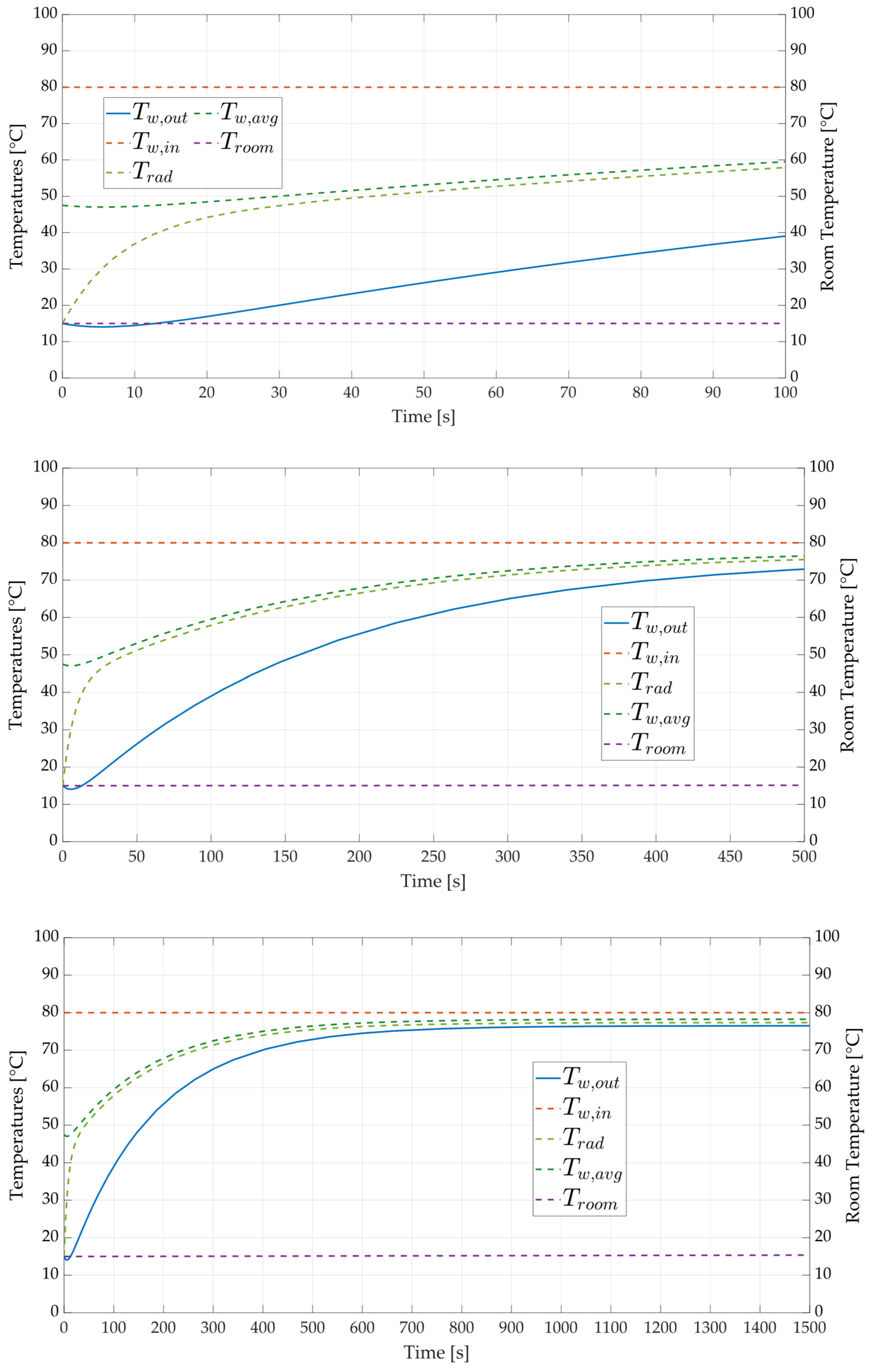

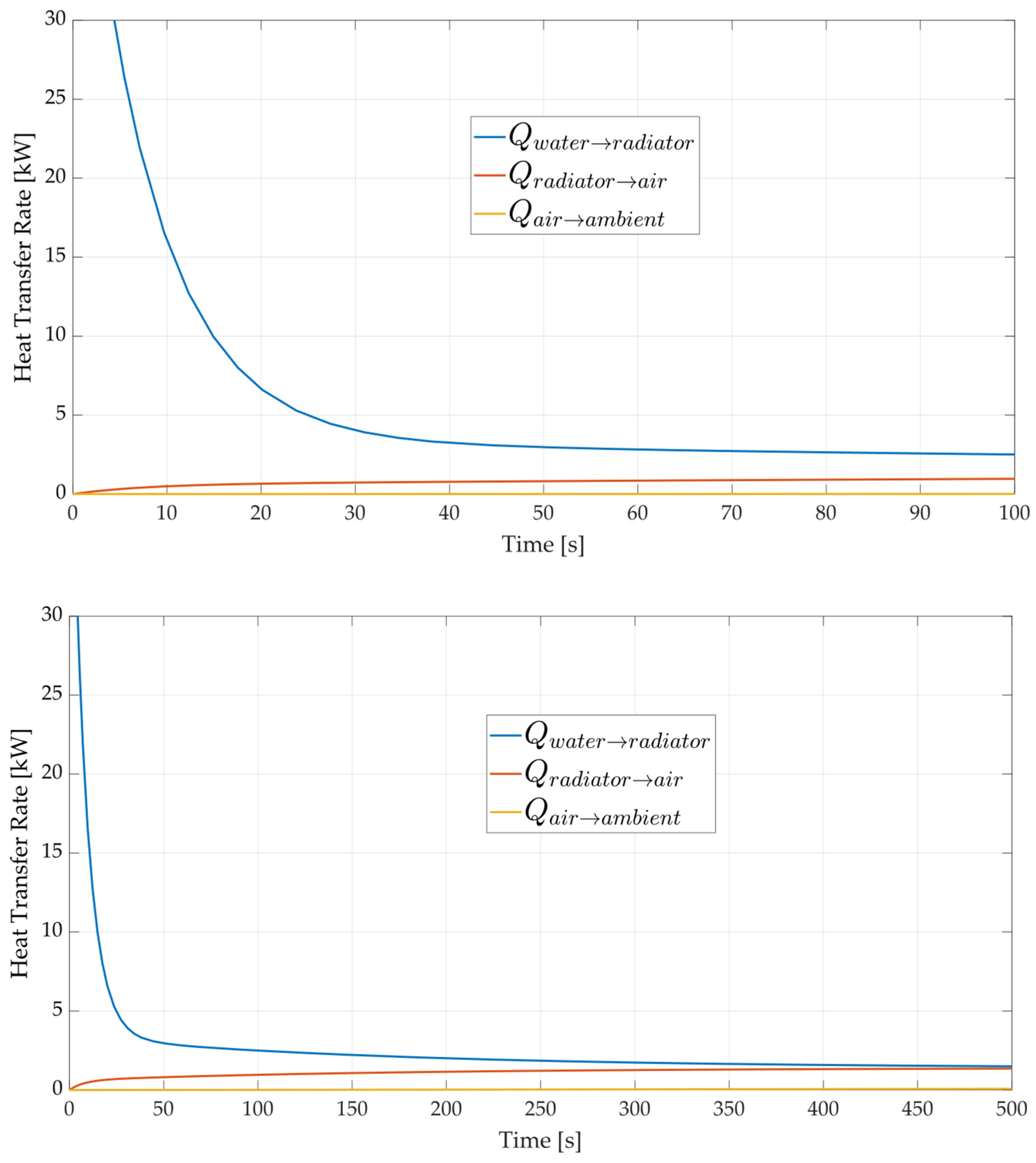

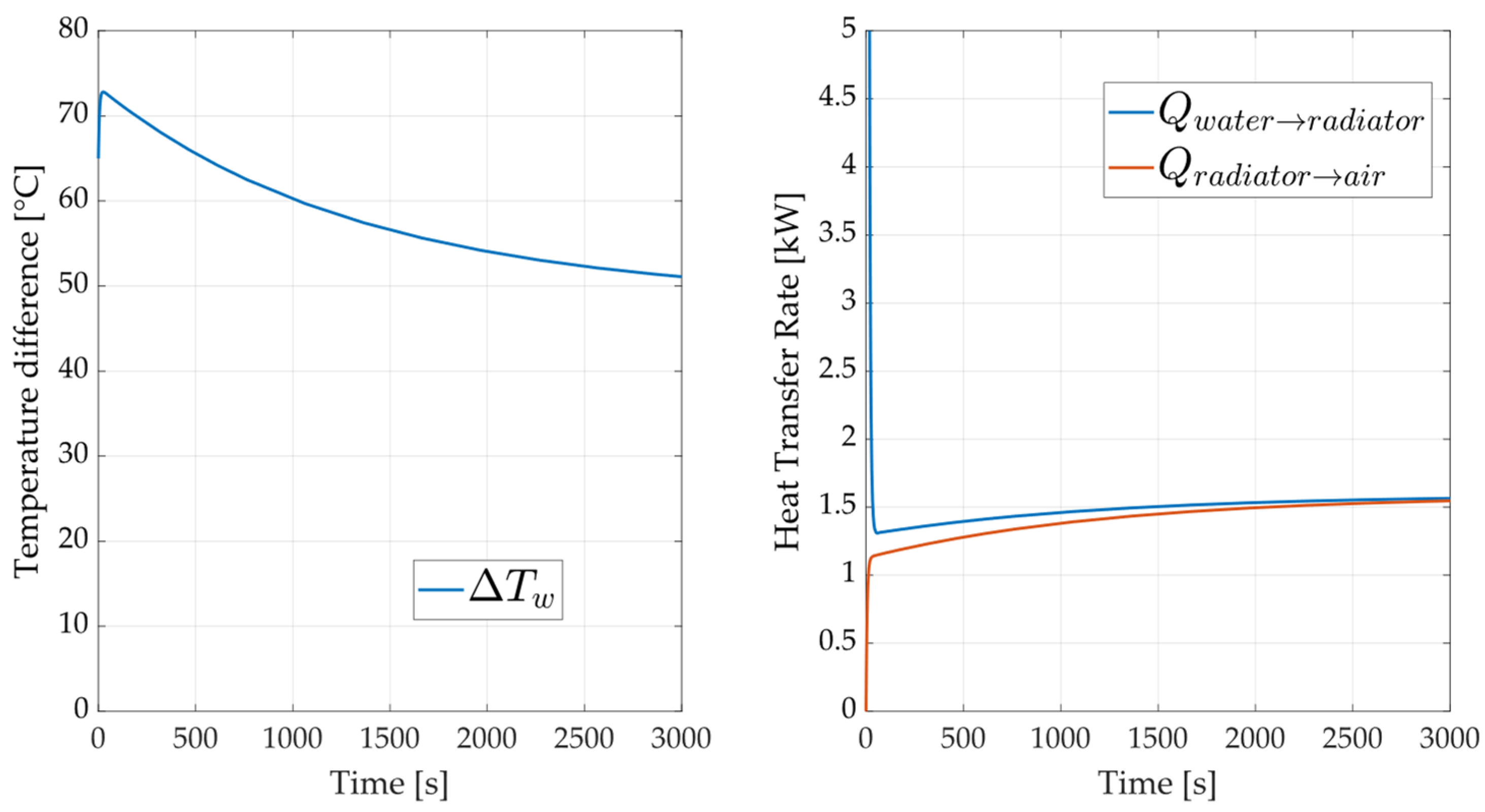

3.1. Transient Heat Transfer Rate

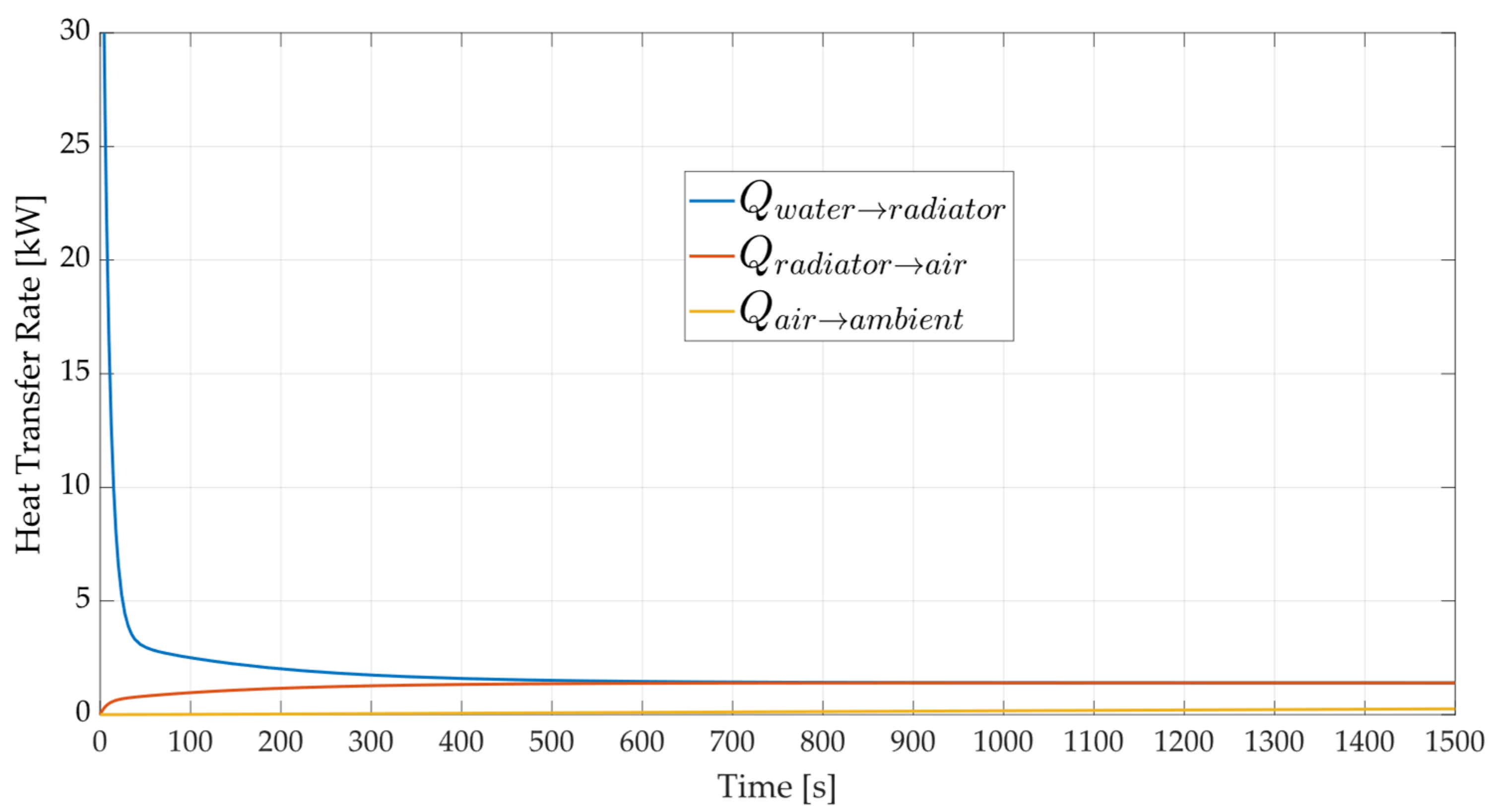

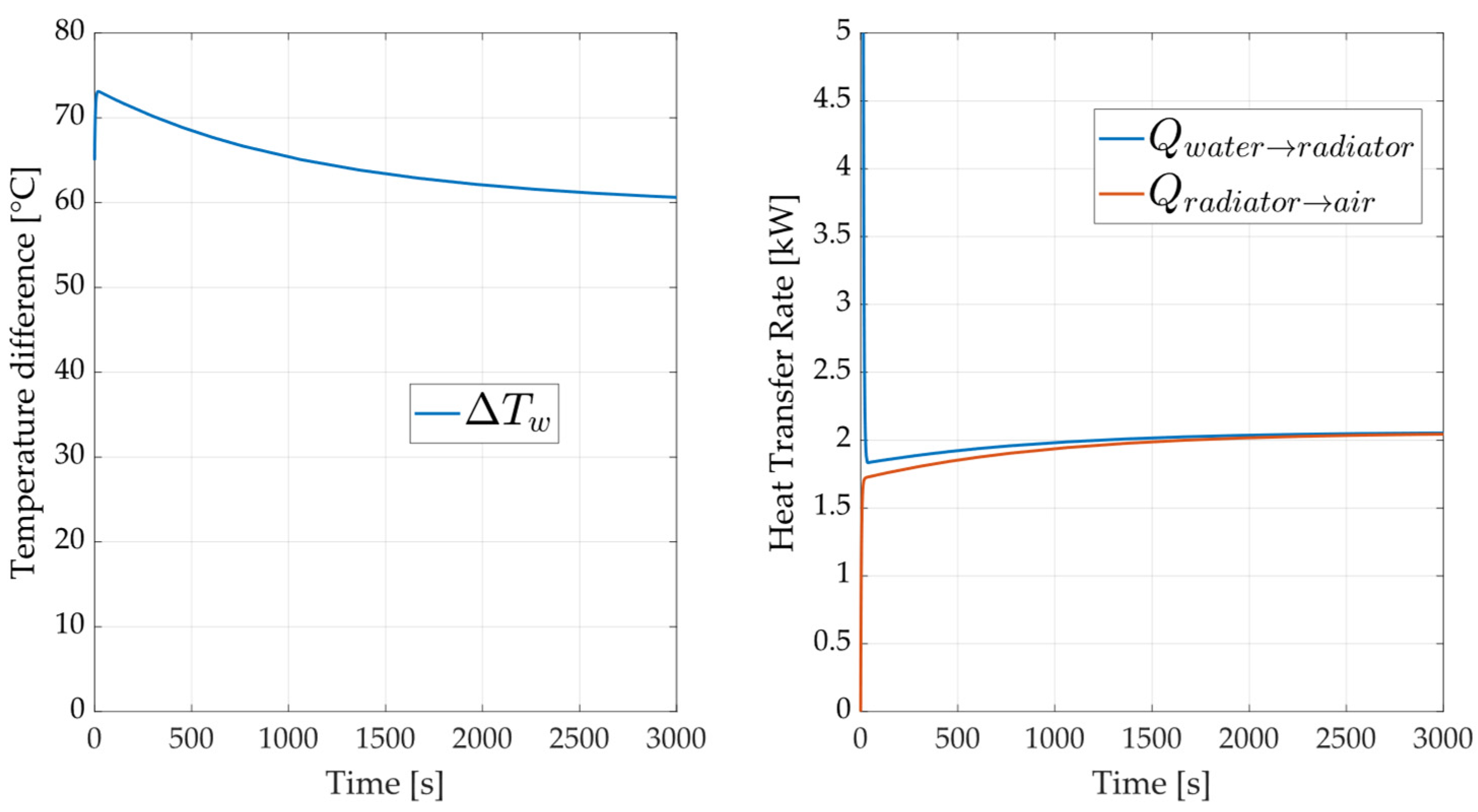

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

3.3. Model Validation

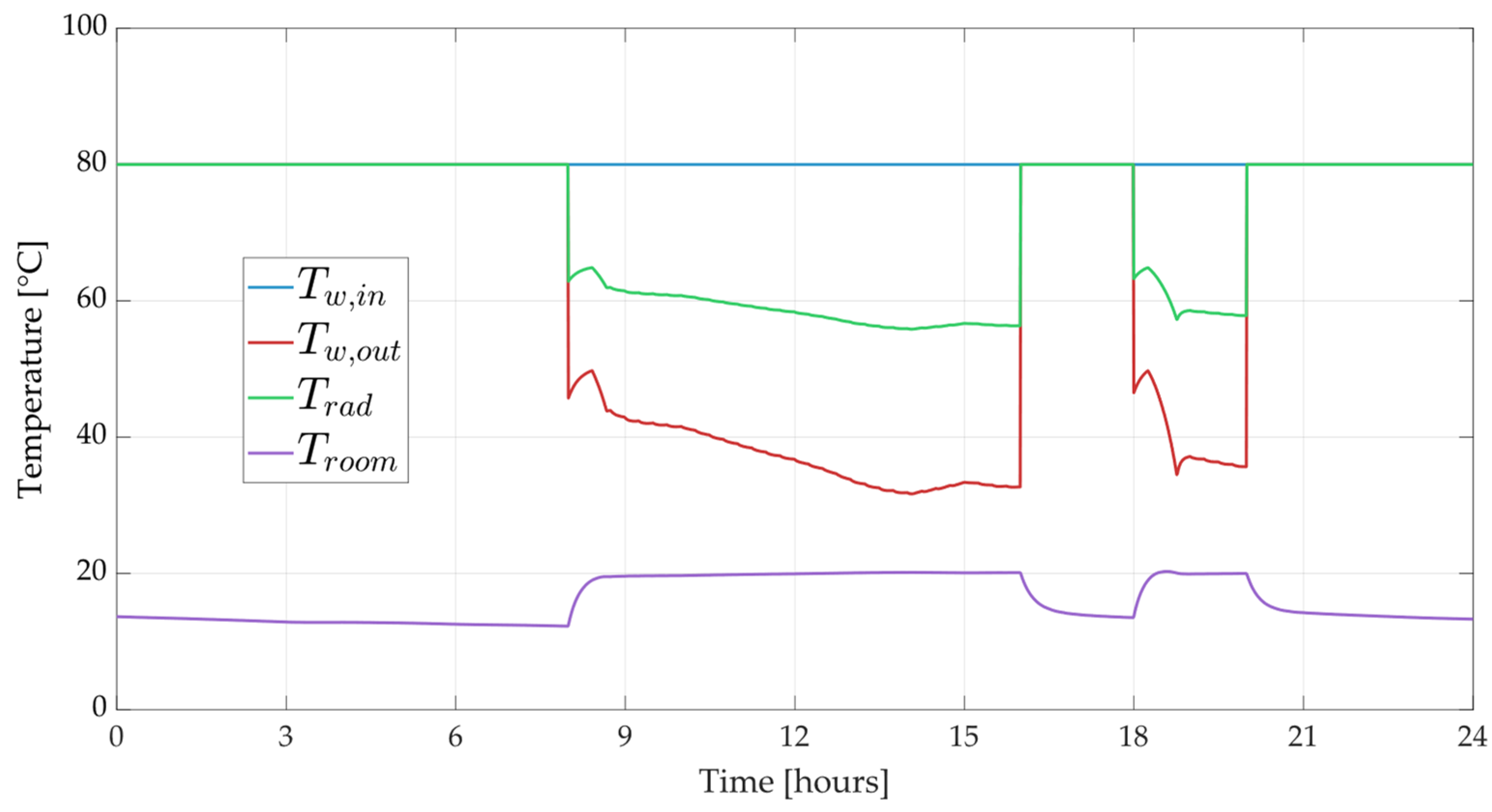

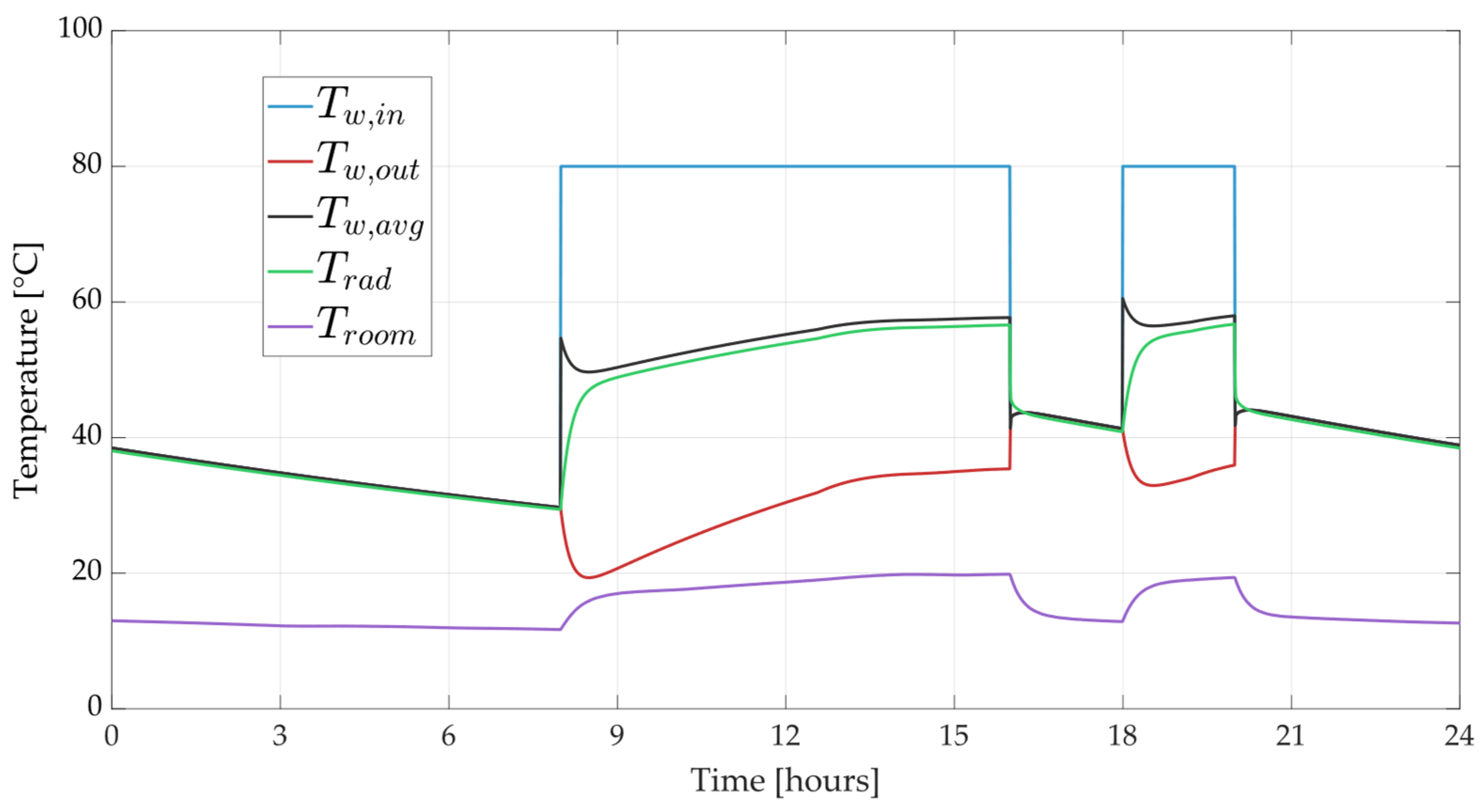

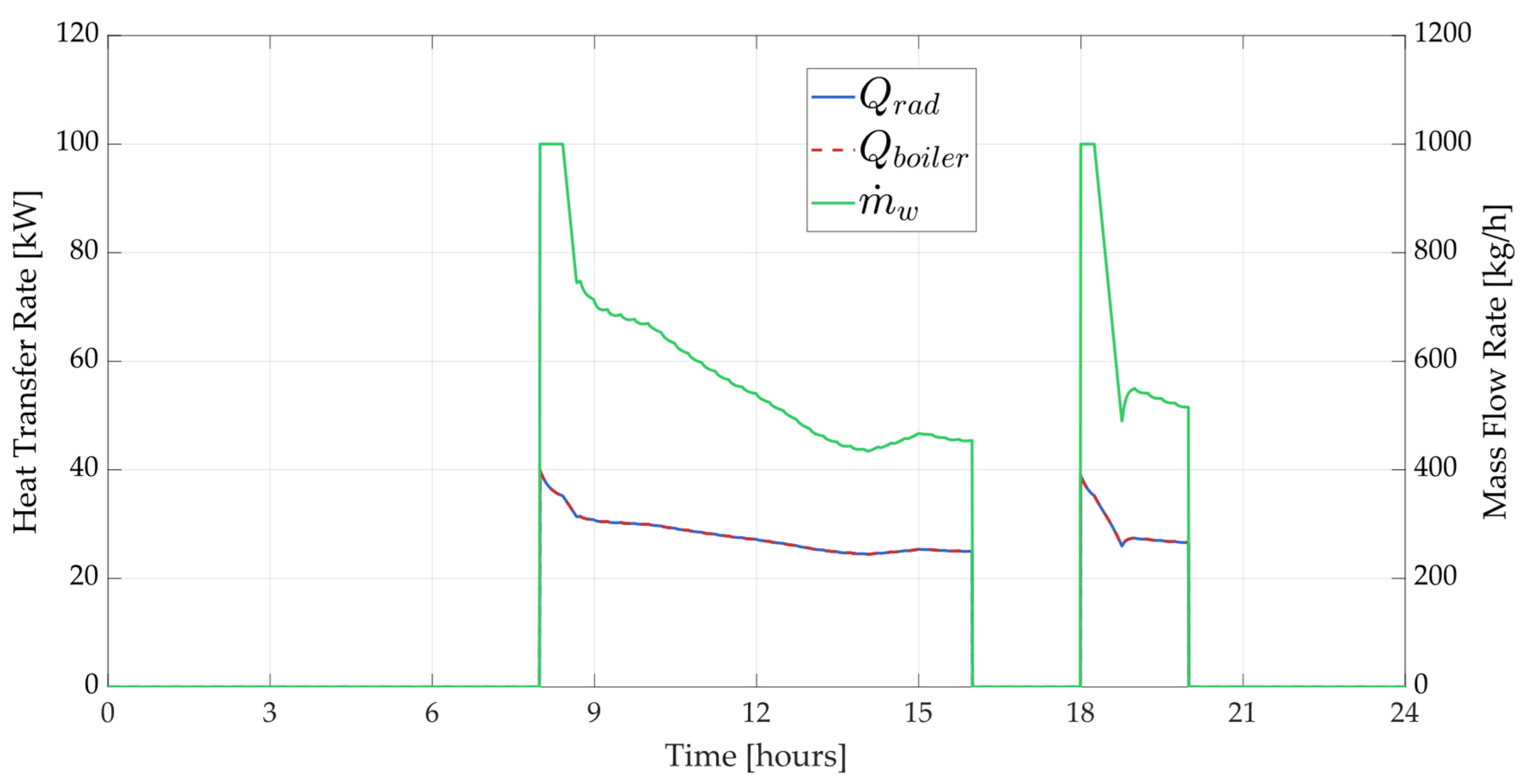

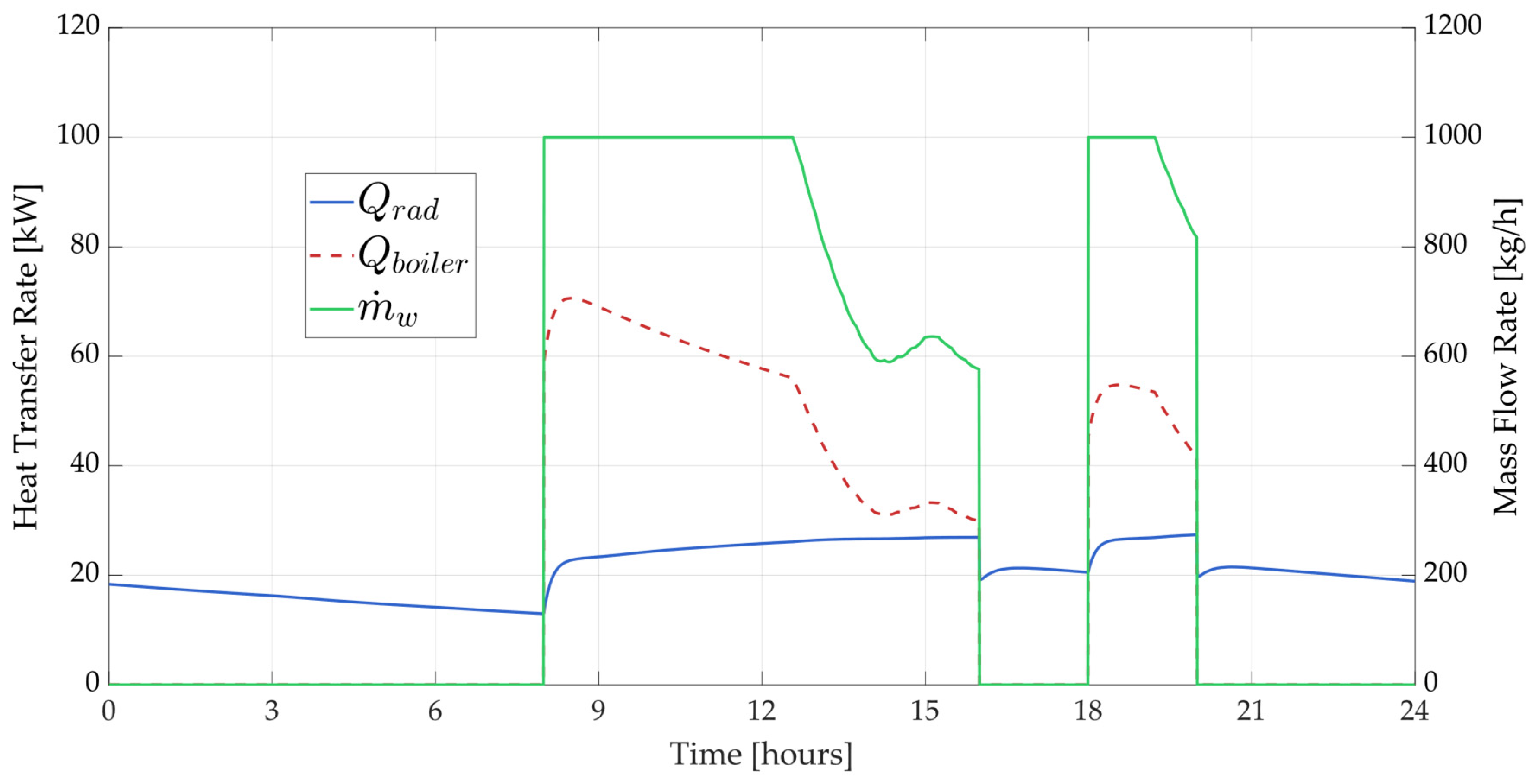

3.4. Comparison with TRNSYS Simulation Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- The capacitive model reveals a distinct transient phase in which the heat transfer from the water to the radiator and from the radiator to the environment is gradual. This results in smoother temperature profiles in both the water outlet and the room air, reflecting a more realistic thermal response.

- -

- Sensitivity analyses underscore that the radiator performance is strongly influenced by the surface area, inlet water temperature, and water flow rate. These parameters critically determine the efficiency of heat exchange and the subsequent energy demand of the heating system.

- -

- The discrepancies observed between the capacitive and non-capacitive models indicate that conventional simulation tools may oversimplify the transient dynamics of radiators. By integrating the capacitive effects, the enhanced model offers improved accuracy in estimating heating consumption and assessing the impact of retrofit strategies on energy efficiency.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daioglou, V.; Mikropoulos, E.; Gernaat, D.; van Vuuren, D.P. Efficiency Improvement and Technology Choice for Energy and Emission Reductions of the Residential Sector. Energy 2022, 243, 122994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Yang, Z.; Yan, D.; Wang, B.; Jiang, Y. Emissions of F-Gases from Room Air Conditioners in China and Scenarios to 2060. Energy Build. 2023, 299, 113561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, R.; Dittrich, N.; Köhler, J.; Müller, D.B. Müller. Embodied Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Structural Materials for the German Residential Building Stock—Quantification and Mitigation Scenarios. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajčík, M.; Arıcı, M.; Ma, Z. Trends in Research of Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning and Hot Water Systems in Building Retrofits: Integration of Review Studies. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, D.; Coakley, S. Transforming Our Buildings for a Low-Carbon Era: Five Key Strategies. Electr. J. 2019, 32, 106624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Japan Will Have to Tread a Unique Pathway to Net Zero, but It Can Get There Through Innovation and Investment. Available online: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/japan-will-have-to-tread-a-unique-pathway-to-net-zero-but-it-can-get-there-through-innovation-and-investment (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; O’Neill, Z.; Wen, J. Temperature Control Strategies for Fifth Generation District Heating and Cooling Systems: A Review and Case Study. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villano, F.; Mauro, G.M.; Pedace, A. A Review on Machine/Deep Learning Techniques Applied to Building Energy Simulation, Optimization and Management. Thermo 2024, 4, 100–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkurt, G.; Aste, N.; Borderon, J.; Buda, A.; Calzolari, M.; Chung, D.; Costanzo, V.; Del Pero, C.; Evola, G.; Huerto-Cardenas, H.; et al. Dynamic Thermal and Hygrometric Simulation of Historical Buildings: Critical Factors and Possible Solutions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 118, 109509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shboul, B.; Zayed, M.E.; Ashraf, W.M.; Usman, M.; Roy, D.; Irshad, K.; Rehman, S. Energy and Economic Analysis of Building Integrated Photovoltaic Thermal System: Seasonal Dynamic Modeling Assisted with Machine Learning-Aided Method and Multi-Objective Genetic Optimization. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 94, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Cappiello, F.; Cimmino, L.; Vicidomini, M. Vicidomini. Semi-Stationary and Dynamic Simulation Models: A Critical Comparison of the Energy and Economic Savings for the Energy Refurbishment of Buildings. Energy 2024, 300, 131618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C.C.; Vaz, I.C.M.; Ghisi, E. Retrofit Strategies to Improve Energy Efficiency in Buildings: An Integrative Review. Energy Build. 2024, 321, 114624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhi, M.; Motallebzadeh, R.; Javani, N.; Ebrahimpour, A. Dynamic Simulation of an Integrated Energy System for Buildings in Cold Climates with Thermal Energy Storage. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordignon, S.; Emmi, G.; Zarrella, A.; De Carli, M. Energy Analysis of Different Configurations for a Reversible Ground Source Heat Pump Using a New Flexible Trnsys Type. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 197, 117413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappiello, F.L.; Cimmino, L.; D’Accadia, M.D.; Vicidomini, M. Dynamic Modelling and Thermoeconomic Analysis for the Energy Refurbishment of the Italian Building Sector: Case Study for the “Superbonus 110%” Funding Strategy. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 213, 118689. [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino, D.; Minichiello, F.; Petito, F.; Renno, C.; Valentino, A. Retrofit Strategies to Obtain a Nzeb Using Low Enthalpy Geothermal Energy Systems. Energy 2022, 239, 122307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Võsa, K.-V.; Ferrantelli, A.; Kurnitski, J. A Combined Analytical Model for Increasing the Accuracy of Heat Emission Predictions in Rooms Heated by Radiators. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 23, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Humire, E.N.; Chiu, J.N.; Sawalha, S. Latent Heat Storage Integration into Heat Pump Based Heating Systems for Energy-Efficient Load Shifting. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 236, 114042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheibi, A.; Rahmati, A. An Experimental and Numerical Investigation on Thermal Performance of a New Modified Baseboard Radiator. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 163, 114324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fan, L.; Xu, X.; Cao, B.; Zhang, H.; Song, L. Experimental Research of the Radiator Thermal Performance Test Equipment and Its Application in Heating System. Energy Eng. 2020, 118, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelis, K. Factorial Experimental Design for Second Law Analysis of Panel Radiators as a Function of Radiator Dimension. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 102872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamian, E.; Ahmadi, P.; Hanafizadeh, P.; Ashjaee, M. Dynamic Feasibility Assessment and 3e Analysis of a Smart Building Energy System Integrated with Hybrid Photovoltaic-Thermal Panels and Energy Storage. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2020, 42, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Li, A.; Feng, A. Research on Heating Performance of Heating Radiator at Low Temperature. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 36, 102016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, A.; Gheibi, A. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of a Modified Hot Water Radiator with Improved Performance. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2020, 149, 106175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, E.; Cruz, E.G. Evolving from an Indirect Evaporative Cooling System to a Radiant-Capacitive Heating and Cooling System for Low-Mass Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verticchio, E.; Martinelli, L.; Gigliarelli, E.; Calcerano, F. Current Practices and Open Issues on the Whole-Building Dynamic Simulation of Historical Buildings: A Review of the Literature Case Studies. Build. Environ. 2024, 258, 111621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priarone, A.; Silenzi, F.; Fossa, M. Modelling Heat Pumps with Variable Eer and Cop in Energyplus: A Case Study Applied to Ground Source and Heat Recovery Heat Pump Systems. Energies 2020, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Viol, V.; Urbano, E.M.; Delgado-Prieto, M.; Romeral, L. Automatic Model Calibration for Coupled Hvac and Building Dynamics Using Modelica and Bayesian Optimization. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, V.; Vanoli, L.; Verde, C.; Nithiarasu, P.; Searle, J.R. Dynamic Modelling of Geothermal Heat Pump System Coupled with Positive-Energy Building. Energy 2023, 284, 128557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bo, S.; Zhu, C.; Hua, P.; Xie, Z.; Xu, C.; Wang, T.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Lahdelma, R.; et al. A Zoned Group Control of Indoor Temperature Based on Mpc for a Space Heating Building. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 290, 117196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, A.; Kavgic, M.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Azzouz, A. Comparison of Energyplus and Ies to Model a Complex University Building Using Three Scenarios: Free-Floating, Ideal Air Load System, and Detailed. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 22, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, D.; Matera, N.; Cornaro, C.; Oliveti, G.; Romagnoni, P.; De Santoli, L. Energyplus, Ida Ice and Trnsys Predictive Simulation Accuracy for Building Thermal Behaviour Evaluation by Using an Experimental Campaign in Solar Test Boxes with and without a Pcm Module. Energy Build. 2020, 212, 109812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesteira, L.G.; Uche, J.; Cappiello, F.L.; Cimmino, L. Thermoeconomic Optimization of a Polygeneration System Based on a Solar-Assisted Desiccant Cooling. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incropera, F.P.; DeWitt, D.P. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 4th ed; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giulio, E.; Di Meglio, A.; Massarotti, N.; Romano, R.A.; Dragonetti, R. Oriented Fibers Stacks for Thermoacoustic Devices. Appl. Energy 2024, 373, 123959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarano, A.; Mazzei, P. Elements of Applied Thermodynamics; Liguori: Barnhart, MO, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Di Meglio, A.; Massarotti, N.; Rolland, S.; Nithiarasu, P. Analysis of Non-Linear Losses in a Parallel Plate Thermoacoustic Stack. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2024, 34, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, A.I.; Butusov, D.; Tutueva, A.V. Adaptive Explicit-Implicit Switching Solver for Stiff Odes. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference of Russian Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (EIConRus), Moscow, Russia, 1–3 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rufai, M.A.; Carpentieri, B.; Ramos, H. A New Hybrid Block Method for Solving First-Order Differential System Models in Applied Sciences and Engineering. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novkovic, M.; Radakovic, Z.; Torriano, F.; Picher, P. Proof of the Concept of Detailed Dynamic Thermal-Hydraulic Network Model of Liquid Immersed Power Transformers. Energies 2023, 16, 3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrae Handbook—Hvac Systems and Equipment; American Society of Heating Atlanta, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://irancanftech.com/book/ASHRAE-HVAC-SYSTEMS-AND-EQUIPMENT-2020.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Iperceramica Spa, Radiatori 2000. The Aluminium Radiators That Are Friendly to the Environment-Helyos Evo. 2024. Available online: https://www.radiatori2000.it/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/HELYOS-Evo-1.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Porto, T.N.; Delgado, J.M.P.Q.; Guimarães, A.S.; Magalhães, H.L.F.; Moreira, G.; Correia, B.B.; de Andrade, T.F.; de Lima, A.G.B. Phase Change Material Melting Process in a Thermal Energy Storage System for Applications in Buildings. Energies 2020, 13, 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, S.; Fotowat, S.; Fartaj, A. Transient Experimental Investigation of Airside Heat Transfer in a Crossflow Heat Exchanger. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 199, 117516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelpa, E. Impact of Network Modelling in the Analysis of District Heating Systems. Energy 2020, 213, 118393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Name | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| hi | Internal heat transfer coefficient | 1500 [36] | W/m2K |

| k | Aluminum thermal conductivity | 236 [36] | W/mK |

| he | External heat transfer coefficient | 15 [36] | W/m2K |

| U | Overall heat transfer coefficient | 14.78 | W/m2K |

| Cp | Aluminum-specific heat capacity | 0.896 [36] | kJ/kgK |

| ρ | Aluminum density | 2700 | kg/m3 |

| A | Surface area | 1.50 | m2 |

| Mr | Radiator mass (empty) | 15 | kg |

| Tw,in | Inlet temperature | 80 | °C |

| ṁw | Flow rate | 342 | kg/h |

| L | Length | 0.88 | m |

| ρw | Density of water | 1000 | kg/m3 |

| Cp,w | Specific heat capacity of water | 4.19 | kJ/kgK |

| Mw | Mass of water | 5 | kg |

| Ta | Ambient temperature | 15 | °C |

| tend | Total simulation time | 500 | s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calise, F.; Cappiello, F.L.; Cimmino, L.; Dentice d’Accadia, M.; Vicidomini, M. A Novel Capacitive Model of Radiators for Building Dynamic Simulations. Thermo 2025, 5, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo5010009

Calise F, Cappiello FL, Cimmino L, Dentice d’Accadia M, Vicidomini M. A Novel Capacitive Model of Radiators for Building Dynamic Simulations. Thermo. 2025; 5(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo5010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalise, Francesco, Francesco Liberato Cappiello, Luca Cimmino, Massimo Dentice d’Accadia, and Maria Vicidomini. 2025. "A Novel Capacitive Model of Radiators for Building Dynamic Simulations" Thermo 5, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo5010009

APA StyleCalise, F., Cappiello, F. L., Cimmino, L., Dentice d’Accadia, M., & Vicidomini, M. (2025). A Novel Capacitive Model of Radiators for Building Dynamic Simulations. Thermo, 5(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo5010009