Co-Design of Social Impact Domains with the Huntington’s Disease Community

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- validate or refute, and map a draft set of HD social impact domains (HD-SID) against existing national and international outcome frameworks; and

- evaluate and finalize the HD-SID set using a co-design approach with people with lived experience of, and expertise in, HD.

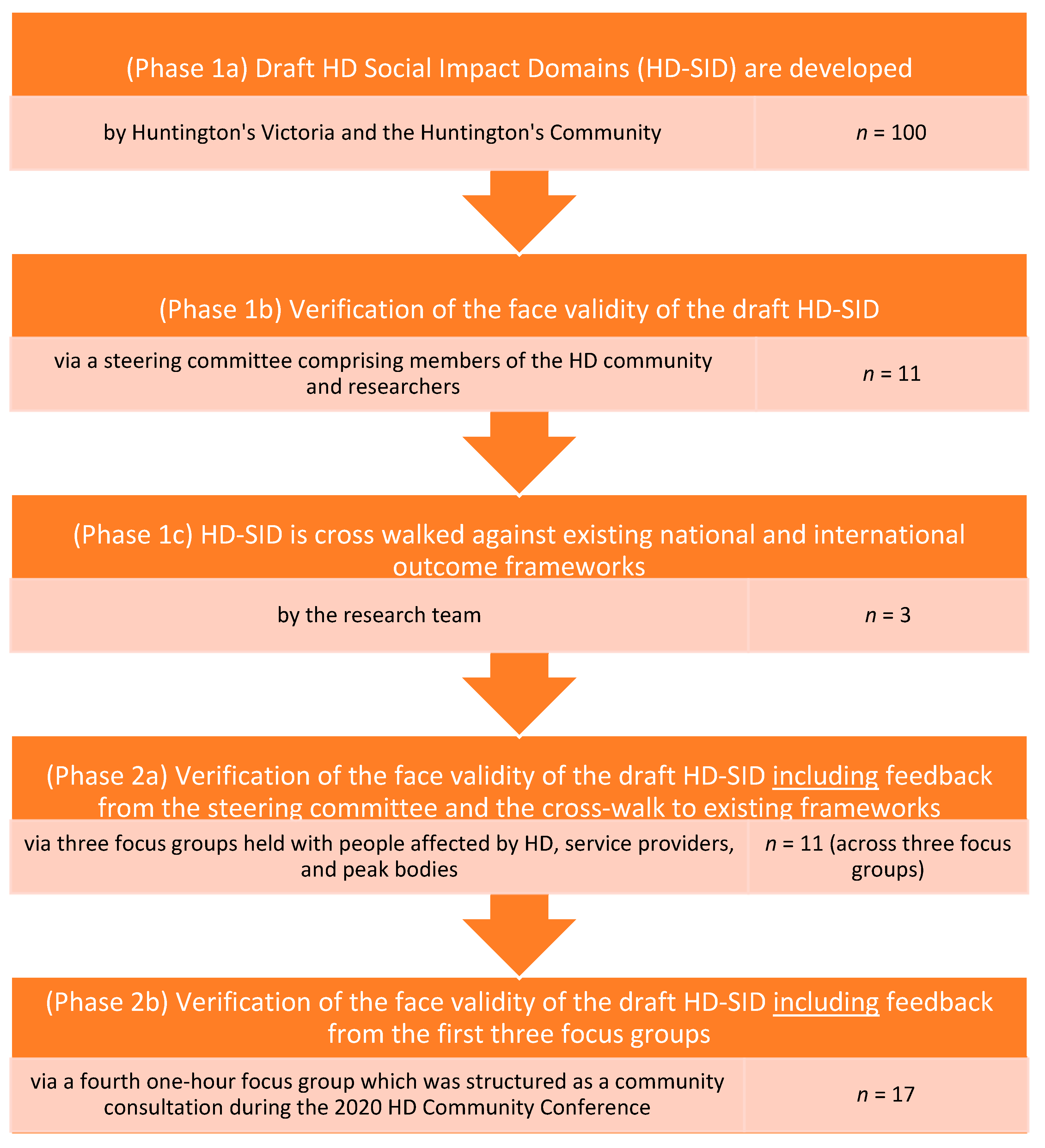

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Verification or Refutation of the Draft HD Social Impact Domains

2.2. Focus Groups

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Management and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Verification of Domains

3.2. Focus Group Perspectives

3.2.1. Findings from Focus Group 1: HD Professionals

- Domain 1 (health and wellbeing) subsumes domain 2 (physical wellbeing): participants discussed how to define health and wellbeing, for example, “Does this [domain] cover more than symptom management and physical health?” (physician). People felt that managing health and wellbeing includes health and symptom management, as well as physical wellbeing. Participants observed that service gaps could occur in psychosocial support services, where there is poor understanding that HD is an organic disease, resulting in the emergence of mental health issues and the need for mental health services.

- The discourse around domain 3 (emotional wellbeing) included domain 4 (social inclusion) and domain 7 (relationships). Civic participation as a desirable outcome for people living with HD mapped to domain 8 (risks and safety). Comments included the need for risk management where “cognitive decline is responsible for social isolation”. Domain 3 (emotional wellbeing), domain 7 (maintaining relationships) and domain 4 (social inclusion) were all deemed at risk if people cannot cognitively manage an “ordered lifestyle”. Domain 5 (housing stability) and domain 6 (economic stability) are foundations for these aspects of emotional wellbeing, with many examples discussed of adverse outcomes for individuals “living in toilet blocks or cars… Struggling with finances, disturbing neighbors, and requiring emergency accommodation” which in turn caused adverse impacts in all other domains. Protective factors include the presence of family. No other areas were identified, indicating saturation in social impacts through the domains presented.

3.2.2. Findings from Focus Group 2: HD Gene-Positive Individuals

- Domain 1 (health and symptom management), domain 2 (physical wellbeing) and domain 3 (emotional wellbeing) were discussed together, with key supports which enable these areas, including “HV support services, HV counselor, allied health, massage, yoga, meditation, aromatherapy (mood-lifter to help with depression), crystal healing, reflexology or pressure point therapy, reiki, positive affirmations” (symptomatic participant).

- The concept of social inclusion (domain 4) was highly resonant and also individualized, and participants discussed their “own ways to find comfort and support for social inclusion”, including “Op shopping, having coffee, hang in cafes and sit and read the paper, hang out, do a bit of people watching, walking on the beach with my fur babies… Pet therapy is really awesome”.

- Domain 5 (housing stability), domain 6 (economic stability) and domain 8 (risks and safety) generated much discussion, with the foundation supports (such as safe and appropriate housing) linking directly to higher-order impacts, “Where can I live? I feel I could live by myself… There is no safe place for time-out” (symptomatic participant).

- When asked if there were other social impacts that had not been captured, participants mentioned the availability of assisted dying/euthanasia, and experiences where professionals failed to “give bad news” appropriately. In contrast, focus group 3 participants below allocated “appropriate professional support” to domain 3 (emotional wellbeing) due to the significant impact of this barrier/facilitator on their overall emotional functioning.

3.2.3. Findings from Focus Group 3: HD Gene-Negative Individuals and Family Members

- Domain 1 (health and wellbeing), domain 2 (physical wellbeing) and domain 3 (emotional wellbeing) were discussed together, as the supports were felt to enable other domains. Examples of professional support were explicitly linked to domain 3 (emotional wellbeing), for example: “(it is) challenging to locate helpful professionals with the skillset and then the knowledge of HD… (I) remember feeling quite frustrated and sometimes paid a lot privately, and they weren’t up to scratch… we would live for them to come that day and they were not informed, really”.

- Housing stability (domain 5), economic sustainability (domain 6), and risks and safety (domain 8) were bundled together with strong narratives around risk. Comments focused on the “falling away” of support when government services changed. For example, “With NDIS, this source of local and timely support (local councils) has fallen away” (family member).

- When asked about other issues not included in the impact domains, participants raised the issue of genetic testing and reflected on poor experiences with health professionals in regard to genetic testing, and “knowing how to support children, relatives, people not yet tested” (gene-negative individual).

3.2.4. Findings from Focus Group 4. Consultation with Members of the HD Community

3.2.5. Summary of Focus Group Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Gap Analysis Focus Group Guide 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Theme | Prompts |

| 1. Introductions |

|

| 2. The idea of a gap analysis | We want to find out about formal and informal support needs. We will be asking questions for each area of life that the HD community, and NDIS, identify as important. We invite you to add any other areas at the end |

| Supports and gaps across areas of life from a human perspective: We will ask the following questions for areas 3–10 —What is an enabler or a support (what helps) in this area? —What is missing in this area? —What is needed in this area (what would “good” look like?) | |

| 3. Health and wellbeing |

|

| 4. Emotional wellbeing |

|

| 5. Social inclusion |

|

| 6. Housing stability |

|

| 7. Economic sustainability |

|

| 8. Relationships |

|

| 9. Risks and safety | |

| Supports and gaps across areas of life from a government perspective: The Commonwealth Government (COAG) describe 11 areas where their policies “intersect” and where there can be service gaps. Tell us what you think about supports and gaps in the following areas: | |

| 10. Formal supports and gaps |

|

| 11. Other? | |

| 12. Thank you… | |

References

- Roos, R.A. Huntington’s disease: A clinical review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Novak, M.J.U.; Tabrizi, S.J. Huntington’s Disease: Clinical presentation and treatment. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2011, 98, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington’s Victoria. Available online: https://www.huntingtonsvic.org.au/understanding-hd#whatishd (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Rawlins, M.D.; Wexler, N.S.; Wexler, A.R.; Tabrizi, S.J.; Douglas, I.; Evans, S.J.; Smeeth, L. The prevalence of Huntington’s disease. Neuroepidemiology 2016, 46, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringsheim, T.; Wiltshire, K.; Day, L.; Dykeman, J.; Steeves, T.; Jette, N. The incidence and prevalence of Huntington’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, N.; Brusco, N. Peer Support for the Huntington’s Community… by the Huntington’s Community, ‘Huntington’s Community Connect’ Part 1: Gap Analysis Report; RAIL Research Centre, Monash University: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Soltysiak, B.; Gardiner, P.; Skirton, H. Exploring supportive care for individuals affected by Huntington disease and their family caregivers in a community setting. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helder, D.I.; Kaptein, A.A.; van Kempen, G.M.J.; van Houwelingen, J.C.; Roos, R.A.C. Impact of Huntington’s disease on quality of life. Mov. Disord. 2001, 16, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, D.F.; Farnworth, L.J.; Sloan, S.M.; Brown, T. Young people in aged care: Progress of the current national program. Aust. Health Rev. 2011, 35, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, E.; Ausserhofer, D.; Mantovan, F. The life as a caregiver of a person affected by Chorea Huntington: Multiple case study. Pflege Z. 2012, 65, 608–611. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, F.O. Huntington’s disease. Lancet 2007, 369, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, R. Peer-to-Peer Counseling for Individuals Recently Tested Positive for Huntington’s Disease. Master’s Thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim, A.; Rangan, V.K. The Limits of Nonprofit Impact: A Contingency Framework for Measuring Social Performance; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vanclay, F. International principles for social impact assessment. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2003, 21, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.; Hocaoglu, M. Impact of Huntington’s across the entire disease spectrum: The phases and stages of disease from the patient perspective. Clin. Genet. 2011, 80, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaptein, A.A.; Helder, D.I.; Scharloo, M.; Van Kempen, G.M.; Weinman, J.; Van Houwelingen, H.J.; Roos, R.A. Illness perceptions and coping explain well-being in patients with Huntington’s disease. Psychol. Health 2006, 21, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National People with Disabilities and Carers Council. Shut Out: The experience of people with disabilities and their families in Australia. In National Disability Strategy Consultation Report; Commonwealth Government: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. National Disability Strategy 2010–2020. 2011. Available online: https://www.dss.gov.au/ (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Centre for Disability Research and Policy, Young People in Nursing Homes National Alliance (YPINHNA). Service Coordination for People with High and Complex Needs: Harnessing Existing Cross-Sector Evidence and Knowledge; Centre for Disability Research and Policy University of Sydney and Young People in Nursing Homes National Alliance: Sydney, Australia, 2014; Available online: https://www.ypinh.org.au/images/stories/pdf/Cross%20sector%20coordination%20paper.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Commonwealth of Australia. National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013. 2013. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2020C00392 (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission. Legislation, Rules and Policies. Available online: https://www.ndiscommission.gov.au/about/legislation-rules-policies (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Council of Australian Governments (COAG). Principles to Determine the Responsibilities of the NDIS and Other Service Systems. April 2013. Available online: https://www.coag.gov.au/sites/default/files/communique/NDIS-Principles-to-Determine-Responsibilities-NDIS-and-Other-Service.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.J.; Rehman, S.S. Mode 3 knowledge production: Systems and systems theory, clusters and networks. J. Innov. Entrep. 2016, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dershin, H. Nonlinear systems theory in medical care management. Physician Exec. 1999, 25, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth, Y. “Is it safe to talk about systems again yet?”—Self organising processes for complex living systems and the dynamics of human inquiry. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2008, 21, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cornwell, T.; Babiak, K. Developing an instrument to measure the social impact of sport: Social capital, collective identities, health literacy, well-being and human capital. J. Sport Manag. 2013, 27, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Soley-Bori, M.; Jette, A.M.; Slavin, M.D.; Ryan, C.M.; Schneider, J.C.; Resnik, L.; Acton, A.; Amaya, F.; Rossi, M.; et al. Development of a conceptual framework to measure the social impact of burns. J. Burn Care Res. 2016, 37, e569–e578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; p. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- NDIA. Quarterly Reports. NDIA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/publications/quarterly-reports (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- National Disability Insurance Scheme. NDIA Working with State and Territory Governments. 2020. Available online: https://www.ndis.gov.au/understanding/ndis-and-other-government-services/ndia-working-state-and-territory-governments (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- The Knowledgeable Patient: Communication and Participation in Health; Hill, S. (Ed.) Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, E.; Pesci, C. Social impact measurement: Why do stakeholders matter? Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 99–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NDIS. Mainstream Capacity Building Grant Round. 2020. Available online: https://www.ndis.gov.au/community/information-linkages-and-capacity-building-ilc/funded-projects#mainstream-capacity-building-grant-round (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Layton, N.; Gardner, T. Session 2 Local research. In Proceedings of the Huntington’s Community Conference; Huntington’s Victoria: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Weate, P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise; Smith, B., Sparkes, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krefting, L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1991, 45, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watchorn, V.; Layton, N. Advocacy via human rights legislation—The application to assistive technology and accessible environments. Aust. J. Hum. Rights 2011, 17, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, M.; Leblois, A.; Cesa Bianchi, F.; Montenegro, V. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities, assistive technology and information and communication technology requirements: Where do we stand on implementation? Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2015, 10, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Domain 1 Health and Symptom Management | |

| Definition of a positive outcome | Achievement of HD symptom stability and overall ongoing maintenance of these symptoms Achievement of overall health separate from HD, that when not attained can negatively impact on the individual |

| Examples | Ongoing active participation in allied health intervention (diet or physical activity) Link to HD specialist for symptom management Continue the management of the health care plan (GP, HD specialist) Managing client progression throughout the various stages of the disease Maintaining physical and cognitive stimulation |

| Domain 2 Physical Wellbeing | |

| Definition of a positive outcome | Achievement and maintenance of the highest possible level of physical independence for stage of disease |

| Examples | Mobility appropriate at the stage of HD Safety in home and community (environment) Physically capable of completing ADLs |

| Evidence points | Equipment accessed to support the individual at home and in the community Allied Health review embedded in care plan |

| Domain 3 Emotional Wellbeing | |

| Definition of a positive outcome | To achieve emotional wellbeing and quality of life when living with HD |

| Examples | Improved mental health Mental health maintenance Improved coping skills and resilience Confidence building Maintenance of self-identity Increased hope Life satisfaction |

| Evidence points | Access to therapeutic intervention (medical and non-medical) Engagement in activities/routines that promote self-worth and identity |

| Domain 4 Social Inclusion | |

| Definition of a positive outcome | To identify as a valued member of their local community. To maintain social connections and networks throughout the disease progression |

| Examples | Strengthening social skills (awareness of HD, self in the HD context) Reduced social isolation/contact/community connections Inclusive and accessible communities Access to venues (dining, entertainment, sporting, etc.) without discrimination |

| Evidence points | Engagement in age-appropriate social activities Engagement in regular community access Capacity building of local venues to enhance community access experiences |

| Domain 5 Housing Stability | |

| Definition of a positive outcome | To either obtain and/or maintain stable housing that meets the support needs at any given point during disease progression |

| Examples | Housing security/safety Housing that is accessible and structured to maximize ongoing support needs (minimized risks of falls, capacity for in-home modification if needed) Cost of rent or mortgage that can be sustained long-term Cost of utilities and other household-related expenses are affordable In-home staff are skilled to meet the care needs of the individual |

| Evidence points | Secured permanent disability accommodation Access to in-home modifications Center-pay or other financial institutions implemented to pay bills and manage funds, as needed Services and supports implemented |

| Domain 6 Economic Sustainability | |

| Definition of a positive outcome | To achieve and/or maintain financial security. To live without financial hardship and be able to afford basic needs. |

| Examples | Maintaining appropriate employment/supporting opportunities for appropriate employment Education/skills development Obtainment of appropriate income stream (Centrelink pension, superannuation, paid employment) |

| Evidence points | In receipt of disability support package (DSP), superannuation, total and permanent disability (TPD) pay Capacity building of workplace for reduced/modified employment Completed training/skill development |

| Domain 7 Building Resilient Relationships | |

| Definition of a positive outcome | To build and/or maintain resilient relationships with partners, family members, friends, carers, neighbors, etc. |

| Examples | Family resilience Reconnecting families/siblings Preventing carer burnout |

| Evidence points | Regular respite opportunities Participated in meaningful activities/quality time together Capacity building of family members |

| Domain 8 Risks and Safety | |

| Definition of a positive outcome | The absence of “behavior” by the individual or toward the individual that places them at risk of harm, or of not achieving the above measures. |

| Examples | Reduced incidents of risks (vulnerable to financial, emotional, sexual, physical abuse) Maintaining service delivery through funded packages Competent and supported decision-making Reduced incidences of “challenging behavior” that places the individual at risk of losing current accommodation, criminal/civil law proceedings, removal/ceasing of critical care need supports, isolation Reduced incidences of industrial relations issues and other acts of discrimination |

| Evidence points | Enduring power of attorney (EPOA) financial, guardianship appointed Behavior management plan implemented Behavioral management services engaged Advocacy within the justice system Advocacy within the legal setting (court, VCAT, tenancy) |

| Social Impacts of HD | NDIS Adult Outcome Domains | WHO ICF | COAG Domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health and symptom management | Health and wellbeing | Body structures and functions Selfcare Learning and applying knowledge General tasks and demands Communication Mobility Products and technology | Health Aged care * |

| Physical well being | |||

| Emotional wellbeing | Choice and control | Mental health | |

| Social inclusion | Daily living Lifelong learning Social, community and civic participation | Community, social and civic life (culture, recreation, spiritual, political) Attitudes Products and technology | Transport |

| Housing stability | Home | Natural environment and human-made changes to environment | Housing and community infrastructure |

| Economic sustainability | Work | Domestic life Major life areas (education, economic) | Education Higher education and VET Employment |

| Building resilient relationships | Relationships | Interpersonal interactions and relationships Support and relationships | Early childhood development |

| Risks and safety | Services, systems and policies | Justice Child protection and family support |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Layton, N.; Brusco, N.; Gardner, T.; Callaway, L. Co-Design of Social Impact Domains with the Huntington’s Disease Community. Disabilities 2021, 1, 116-131. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1020010

Layton N, Brusco N, Gardner T, Callaway L. Co-Design of Social Impact Domains with the Huntington’s Disease Community. Disabilities. 2021; 1(2):116-131. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1020010

Chicago/Turabian StyleLayton, Natasha, Natasha Brusco, Tammy Gardner, and Libby Callaway. 2021. "Co-Design of Social Impact Domains with the Huntington’s Disease Community" Disabilities 1, no. 2: 116-131. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1020010

APA StyleLayton, N., Brusco, N., Gardner, T., & Callaway, L. (2021). Co-Design of Social Impact Domains with the Huntington’s Disease Community. Disabilities, 1(2), 116-131. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1020010