Abstract

Globally, adolescents and young adults are calling for action from governments on global humanitarian crises, taking on leadership roles that have contributed to redefining leadership in terms of behavior and action rather than qualities and status. However, there is a significant gap with regard to the conceptual and theoretical understanding of how adolescents and young adults experience leadership. In this paper, we present the results of two qualitative studies that examined the phenomenon of leadership among adolescents and young adults. Study 1 involved interviews with young adult leaders to analyze the fit between traditional leadership theories and their experience of leadership. Following this, Study 2 utilized the results from Study 1 to design a diary study of adolescents attending a leadership program. Both studies revealed that leadership is experienced as a pathway that involves three mechanisms of transferability: sensemaking, action and reflection. The findings of the studies are contrasted with traditional models of leadership that underrepresent the developmental nature of leadership and the transferability of leadership skills across different environments.

1. Introduction

Despite the view that childhood and adolescence are important stages for adult leadership development and performance, there is little empirical evidence to support this view [1]. There is a significant gap regarding the conceptual and theoretical understanding of how adolescents and young adults experience leadership [2]. The three main theories of leadership (the path-goal theory, the contingency theory and the transformational/transactional theory) have not adequately accounted for how youths develop as leaders and there is limited literature on how these theories apply to young adults and adolescents. Understanding leadership among adolescents and young adults has been central to psychology, sociology, and pedagogy but it has typically been examined under different headings, e.g., “social interaction”, “sociometric status”, “deviant peer influences”, “interpersonal development”, and so forth [3,4]. The current literature is missing a well-established theory of youth leadership development from young people’s own experiences and views about leadership.

This gap in the literature is in contrast to the increasing numbers of young people that are assuming leadership positions. Globally, children and adolescents are calling for action from governments on global warming and the environmental crisis. For example, one significant action came from six adolescents from Portugal who sued 33 countries for not doing enough to reduce emissions and fight climate cha nbnge [3]. In addition, high-profile individuals such as Greta Thunberg, Vanessa Nakate and Malala Yousafzai have taken leadership roles and, in doing so, have provided role models for younger people as to how to take agency. They are contemporary examples of leadership in terms of behavior and action rather than leadership as something defined by qualities and status. Moreover, young people are positioning themselves as leaders in the virtual world via YouTube vlogging, TikTok and Reddit. This highlights the importance of studying the contextual development of leadership rather than relying on methods that seek to identify leadership styles.

However, not all examples of peer leadership are positive. There is considerable evidence of negative peer influence [4]. Both positive and negative examples of adolescents’ leadership can be viewed through the lens of peer and adult modelling, but there is relatively little literature on developmental models for leadership. Through their interaction with their peers, students can develop a strong sense of community, social integration and a rich network of resources [5], which are all elements of leadership. Thus, it is useful to examine leadership during adolescence as what occurs during an individual’s developmental years can have an impact on the leadership exhibited later in the workplace or in other positions as an adult [6]. Additionally, studying adolescent displays of leadership could further our understanding of adult leaders as well [7]. Understanding youth leadership necessitates an appreciation of how the contemporary context has changed in terms of the way that developments in the virtual sphere have enabled and encouraged youth voice. Moreover, such activities are supported by their families and networks.

The state-of-the-art is indicative of a major research and literature gap on adolescent leadership development and adolescent leadership models [2]. Quantitative methods require a pre-existing model or approach to be tested in the form of hypotheses and/or predictions; a review of the literature suggests that no such models have been established for adolescent leadership development [2]. Thus, an exploration of adolescent leadership without being anchored in any specific adult leadership model or theory emerged as the most meaningful way to add to the state-of-the-art of this phenomenon. It is well-established that qualitative methods are adequate “tools” to utilize when focusing on exploring ideas and formulating frameworks that will provide an understanding of a relatively unchartered domain like adolescent leadership development. To that end, two qualitative studies were conducted to explore the experiences and views of adolescents and young adults with regard to leadership development contributing to the development of an initial theoretical framework for the process of leadership skills transferability in young persons. Study 1 involved interviews with young adult leaders to analyze their experience of leadership. Following this, Study 2 utilized the results from Study 1 to design a diary study of adolescents attending a leadership program aiming at understanding the participants experiences of transferability of leadership skills.

2. Study 1

2.1. Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of young adults who assumed leadership roles in youth organizations via retrospective interviews in order to understand more about how their experiences have inspired and informed their understanding of themselves and others as leaders in their current positions.

The research questions were:

- How do young adults positioned as leaders in youth organizations conceptualize leadership?

- How do young adults positioned as leaders in youth organizations describe the characteristics of effective leadership behavior?

- What are the components of leadership teaching and development that young adults who are positioned as leaders in youth organizations perceive to be effective?

2.2. Materials and Methods

2.2.1. Design

A qualitative study with semi-structured in-depth interviews was conducted. While other methods of data collection have been widely used among young adults effectively (e.g., focus groups), semi-structured interviews were deemed as the most appropriate method for this study in terms of fitting with the aims—to collect detailed and in-depth accounts on each participant’s experience from a single perspective at a time [8]. Thus, the design of the study was driven by the aims. Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) was used to analyze the collected data and produce relevant themes and sub-themes informed by the critical realism approach. Critical realism combines a realist ontology with an interpretive epistemology [9,10], which assumes that there is a real world, but our knowledge of the world is socially constructed and, therefore, fallible [11]. The emphasis was on explaining how adolescents and young adults form their understanding of leadership, which experiences they describe as influential and what real entities and structures could be identified as mechanisms. Mechanisms are at the center of a critical realist methodology, and on a general level, they can be defined as reciprocally causal structures that can potentially trigger events [11]. The complexity of leadership development, especially during a very critical developmental stage like adolescence/young adulthood, requires a methodology that accounts for a contextual understanding of the outcomes of the various mechanisms involved. Critical realism allows for a contextual approach; thus, the focus was on exploring contextual mechanisms that might produce different outcomes in different contexts under the limitations that reduced the generalizability of the research findings. By informing the analytic approach with the critical realism methodology, we assume that the real entities and structures that were presented as potential mechanisms are mainly used to explain the phenomenon of adolescent leadership and not to predict it; this means that the principle of contingent causality was used [12]. The utilization of contingency causality has been used frequently in the study of leadership [13,14].

2.2.2. Participants

In total, 15 young adults were interviewed, and the sample was comprised of eight female and seven male participants. The mean age was 22 years old, ranging from 21 to 23 years, and they were all undergraduate university students (Table 1). All participants were currently active in a youth organization and performed a leadership or coordinating role. Most of the participants were members of youth organizations with a mission to enable youth to develop leadership qualities through their experiences in international internships, volunteer opportunities and projects, as well as influence the world for the better. Participant recruitment was conducted via invitations posted on online university platforms and social media groups/pages related to university students. Convenience and snowball sampling were used. Before the interviews, researchers explained the purpose of the study and confidentiality was guaranteed. Participant names were replaced with pseudonyms in all stages of recording, analysis and reporting. Participation in the study was voluntary, and participants gave their consent to the recording of the interview. Participants were interviewed individually in an office that was quiet, and the average time of interviews was 30 min. Any attempt to define sample size based on data saturation was deemed unnecessary, as according to Braun and Clarke [15], data saturation is not consistent with the values and assumptions of RTA, especially since meaning is generated through the interpretation of data (and not excavated from data); therefore, judgements about saturation are most often subjective and cannot be predefined prior to the completion of the analysis.

Table 1.

Information about the participants.

2.2.3. Data Collection

Data was collected using semi-structured interviews (April–May 2018). Semi-structured interviews were used as such an approach allows the researcher to frame the questions while providing the opportunity for open exploration of identified issues [16]. Semi-structured interviews consist of a preconceived interview plan, allowing, however, great flexibility in the order that the questions are asked, in the modification of their context according to the interviewed party, as well as the adding and subtracting of questions [17]. Prior to the interviews, a pilot assessment of the interview guide was shared with 17 individuals (20–24 years old) to assess face validity. It was important to ensure that prospective participants would not find the topic alienating or difficult to comprehend. Two of the questions were changed as the participants considered them not to be clear. The final interview guide included 20 questions which were developed on the basis of the literature [2]. The interview was conducted using only open-ended questions, allowing the participants to freely elaborate on their ideas and opinions without restrictions [18].

2.2.4. Data Analysis

Data was collected via interviews and analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) [15]. RTA has entered the “canon” of qualitative research as a well-known and widely used method for analyzing qualitative data since the publication of the original article by Braun & Clarke in 2006 [19] as Thematic Analysis (TA). Most recently, the authors have suggested RTA as an even more flexible approach to generating themes from qualitative data. According to Braun and Clarke [19,20], TA offers a method for identifying patterns (‘themes’) in a dataset, and for describing and interpreting the meaning and importance of those.

RTA, as developed by Braun and Clarke [15], is not a priori grounded in any specific theoretical paradigm and can be applied across different ontological/epistemological paradigms. This fits within the ‘big Q’ qualitative approach, the application of qualitative techniques within a qualitative paradigm, as opposed to the “small q” qualitative research, used to classify qualitative research in more quantitative—positivist models [21]. The six steps have remained the same as in the initial Braun and Clarke [19] TA paper, informed now by the flexibility of the revised reflexive TA (Table 2, the six phases of reflexive TA adapted from Braun and Clarke as cited in [22]).

Table 2.

The six phases of reflexive TA adapted from Braun and Clarke (as cited in [22] p. 2014).

Thematic analysis has been previously used to examine the experiences of adolescents who participated in leadership programmes [23,24]. Parkhill et al. [24], using a constructionist approach and interpretivist framework, found the following themes: the development of resilient attitudes, the identification of a personal leadership style, and the development of a sense of group belonging. De Jongh et al. [23] explored a group of learners’ experiences of their participation in a leadership camp and how this developed their leadership skills. The researchers conducted two focus groups with six learners and identified four themes using thematic analysis; becoming myself, learning life’s lessons; ‘I can take on the world’, and health-promoting schools. Thematic analysis can be used to analyze most types of qualitative data, including qualitative data collected from interviews, focus groups and diaries. The theoretical and research design flexibility of TA allows researchers advantages, including that multiple methods can be applied to this process across a variety of epistemologies [19], it allows for inductive development of codes and themes from data [25], and is applicable to research questions that go beyond an individual’s experience [26]. The analysis was informed by a constructionist approach with an interpretivist framework. A similar approach was used by Parkhill et al. [24] and De Jongh et al. [23], who also explored the views of young learners regarding leadership training and development.

2.2.5. Ethical Considerations

The research protocol for the research (i.e., research design, data collection, and ethical procedures) was approved by the University of Macedonia prior to the research being conducted (Ref. No. 428/05-03-2018). Moreover, the ethical procedures according to the Declaration of Helsinki when conducting research with human participants during all phases of the present study were followed. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their participation in the study. The consent form that was addressed to the participants clearly stated what they would be doing, thereby drawing attention to anything to which they could conceivably object. Participants were informed in detail of the purpose and the process of the study and were informed that their participation was voluntary, and they were free to withdraw at any time. Furthermore, the measures taken to ensure the confidentiality of data were communicated to the participants.

2.2.6. Reflexivity Statement

The authors (DK, AM) have been actively involved in leadership training for adolescents and young adults prior to and during the time the study was conducted. During the data collection (DK) and data analysis stages (DK, OL) the involved authors engaged in reflexivity (reflexivity diary logs) to identify potential sources of researcher bias. The authors’ experiences as a school psychologist in Greek high schools (DK), prior interactions with adolescents and young adults in the broader educational context (DK, OL) as well as views in favor of integrating leadership skills training in the school curricula have been identified as potential sources of bias.

2.3. Analysis

Theme 1: “Comprehensive” definitions of leadership.

Participants shared their ways of defining “leadership”; those definitions are described as “comprehensive” in this theme, as they were attempts to communicate the participants’ “wide mental grasp” of comprehensive knowledge around what leadership is. Excerpts included in this theme show the participants’ attempts to communicate their understanding of leadership in a broad manner, using broad and wide concepts that incorporate a lot of qualities, skills and behaviors that comprise their conceptualization of leadership. This theme consists of the following sub-themes: (1) Leadership, as the ability to “Inspire and Motivate” and (2) Leadership, as the “Leader”. The definitions of the sub-themes reflect the broader concept around which the participants built their “comprehensive” definitions of leaders.

Sub-Theme 1: Leadership, as the ability to “Inspire and Motivate”.

In this sub-theme, leadership was conceptualized as the ability to inspire or motivate other people. In Excerpt 1, participant Lucas identifies the word “inspiration” as the “keyword” for his conceptualization of leadership, almost as if there can be no leadership without inspiration. In Excerpt 2, the participant Sophie also uses the word “inspire”, while the use of “even” seems to be suggesting that if somebody can inspire people just by sharing their experiences, they can be named “leaders”.

Excerpt 1: “I believe that leadership is an inspiration. For me, the keyword is inspiration in leadership…to be able to inspire the people around you about something…”.(Lucas)

Excerpt 2: “I think people that are leaders, even if they just talk about their experiences, they inspire you. So, you start to see, try how you can do it as well, adapt it to yourself.”(Sophie)

In Excerpt 3, the participant Vicky makes an attempt to use a descriptive definition of inspirational motivation to define leadership, in contrast to manipulation, which is excluded from her comprehensive understanding of leadership. Excerpt 4 incorporates the idea of inspiration and motivation, similar to the previous excerpts. Thus, leadership is reflected in the ability to inspire other people and motivate them to achieve their own dreams:

Excerpt 3: “A leader is not somebody who will manipulate you into a specific direction but somebody who will make you stronger so you can follow your direction based on yourself.”(Vicky)

Excerpt 4: “…The image of a leader (…) [is in] their capacity to transform their personal experiences into life lessons they can motivate the people below them to go after their dreams and also to feel strong enough that they can succeed.”(Ann)

It is important to note that in this sub-theme, there is an implicit emphasis put by the participant on the ability to inspire. This is an important structure, potentially indicative of a conceptualization that sees leadership as an ability exhibited by a person and not as a person exhibiting an ability.

Sub-Theme 2: Leadership, as the “Leader”

For other participants, leadership overlaps with the person in the leadership position, thus the “leader”, as the person who possesses particular qualities/characteristics, skills or exhibits particular behaviors. In Excerpt 5, participant George states that his definition of leadership is “through the leader, better”; thus, leadership is not comprehended as an action alone or an abstract notion but rather as a person. The implicit emphasis on the person (the leader) can also be extracted from the very generic phrasing in Excerpt 5; “managing” is a neutral word, and the phrasing “some affairs” suggests that little significance is put on the processes or mechanisms between the person-leader and the achievement of a goal:

Excerpt 5: “I can define leadership ‘through’ the leader, better. [A leader] is somebody who manages a team or some affairs aiming to achieve a goal.”(George)

In Excerpt 6, participant Helen defines “leadership” by describing a “real leader”; the “real” leader is a person who “does not sound fake” and does not make things look more difficult than they are; a potential implication here is that the “not real leaders” would probably be persons who although might be in leadership positions, are not really leaders:

Excerpt 6: “A real leader is a person who does not sound fake and also does not make things look difficult when they are in charge of a project or a team.”(Helen)

In Excerpt 7, the participant is transitioning from the “leadership as a capacity” to the “leadership as a person” comprehension. Leadership is comprehended as a person with self-awareness of their strengths and weaknesses rather than, e.g., the capacity to manage one’s strengths and weaknesses effectively.

Excerpt 7: “Leadership is the capacity to, first of all, be the leader of yourself, which means to know what are your strengths that you can rely on but also to know your weaknesses…”(Karoline)

Compared to the previous sub-theme, here the analysis generated a comprehensive pattern based on the “leader” with an emphasis on the personal/individual aspects of being a leader rather than the ability to exhibit “leadership”.

Theme 2: Viewing the self as a leader ”I am a leader only with a team”

The second theme was generated from the excerpts where participants shared their views of themselves as leaders. Participants discussed their observations and experiences regarding how they view themselves as leaders. In the following excerpts, the participants view themselves as leaders in relation to taking responsibility for something and in relation to how they behave toward other people. In Excerpt 8, the participant states that she could view herself as a leader because she can take responsibility for something and successfully deliver it, as well as by putting a lot of effort into how she behaves towards other people. In Excerpt 9, the self as a leader is also viewed in relation to other people; however, in this case, the participant can see herself as a leader only when being in a team and not independently, as an individual.

Excerpt 8: “I could be yes (a leader), why not? Because I can definitely be responsible in something that I will do, if I take it on, I will definitely want it to be perfect. I put a lot of thought in how I will behave towards other people…”.(Jessica)

Excerpt 9: “I believe that through teamwork leading teams might emerge…with good management and goal achievement. I don’t think that I am a leader by myself, only with a team.”(Christine)

In a similar way, in Excerpts 10 and 11, the participants also draw upon their experiences and observations that involve the self as a leader while being in a team. In this sense, some of the participants view themselves as leaders when they can connect with people, “influence” them and “make them fanatical” about the project (Excerpt 10) or because they can “communicate well” with other people (Excerpt 11). There is a strong contextual component that can be identified when participants discuss their own ability to lead, e.g., how other people have responded to them or how well they can interact with other people. Their views of themselves as leaders are dynamic, experience-based and depending on how other people respond to them and interact with them.

Excerpt 10: “… I can attract people towards something that I like, in a team for example, if it is something that I like that the team will do…. If this is leadership, then I am a leader. But yes…hmm…with this definition I am a leader. For example, I am a person who connects the people around her (…). I am a person who will connect people and make them fanatical about an issue. In that sense, I am a leader, you could say that.”(Jessica)

Excerpt 11: “… I think I am a good leader but based on the model that I will communicate with the other (person), I will make fun, I will say a few more words and then I will handle the person in a good sense, that this is what we have to do now, of course, there is a lot more I have to improve, I am very “soft”, very mild, but until now I have had good results, I have not been in a situation where I would say “this has led to a very negative result.”(Christine)

Although the explicit focus is on the participants’ skills and experiences that they perceive can portray them as leaders, the implicit pattern emerging is that in the examples shared, the other people did not “oppose” their leadership attempts. From a leadership development perspective, this is potentially an important factor, especially for young people, whose self-views of leadership are at an emerging stage, fragile and sensitive to external validation (or invalidation); the degree to which people around them “embrace” their leadership seems to be a critical mechanism that can enable and/or constrain their actions and the views of themselves as leaders.

Theme 3: What makes a good leader: Safety vs. Authoritarianism.

Within their interviews, participants referred to some of their observations and experiences that indicate qualities they view as either positive or negative when it comes to leadership. Thus, this theme included two subthemes: One, Good leadership means enabling a sense of control and psychological safety and two, Steering away from authoritarian leadership.

Sub-theme 1: Good leadership means enabling a sense of control and psychological safety.

The participants identified various behaviors and attitudes that they perceive to be positive; on a latent focus level, those different attributes seem to be all connected as necessary conditions to allow the team members to have a sense of control and feel psychologically safe. In the following excerpts, participants mainly speak from the position of the team member or the observer; they are sharing their experiences and their observations of other people as leaders.

In Excerpt 12, knowing what each member should do in a team is perceived as a positive aspect of leadership as well; speaking from the position of a team member, the participant shares her own experience of safety; the phrase “I felt safe” has a very powerful meaning here as well as the choice of the word “control”:

Excerpt 12: “When I knew what I had to do, I felt safe and could control my time and emotions. When you know your duties, it is easier for you and the team.”(Ann)

Similarly, the ability of a leader to control the way they express themselves and mediate conflict to restore safety in the team is also perceived as a positive quality (Excerpt 13). Listening, expressing views, having empathy for others, and accepting criticism are also components that help construct the importance of experiencing safety and a sense of control as members of someone’s team:

Excerpt 13: “… listen, be able to express correctly what they think because it is very important to transmit what you are saying; it is not what you say, it is the way you say it, be a mediator, and be able when they are between two sides to function as the link that will connect and not take one’s side…”(Jim)

Other participants reported that receiving justification and discussing the procedure was significant to them in order to understand the thoughts and actions of the team members. When they knew the reasons, that helped them feel safer and in control, as seen in Excerpt 14. Being able to understand the need for help and communicate that need is a positive leadership quality. In order for a team member to ask for help, a psychologically safe climate would be required (Excerpt 15).

Excerpt 14: “She was always justifying why the members of the team had to do the specific task, and that made us feel very good.”(Mary)

Excerpt 15: “In a situation that I could not handle the time pressure, I asked for help. I knew it was the best thing to do at the time.”(Christine)

Sub-theme 2: Steering away from Authoritarian Leadership.

Qualities of leaders that are viewed by the participants as negative seem to be falling under the label of “authoritarian style” behaviors. This is opposite to the previous sub-theme; observations and experiences in this sub-theme indicate the absence of psychological safety and lack of a sense of control and are rather indicative of authoritarian leadership. In the following excerpts, participants reported attitudes and behaviors such as: imposing views (Excerpt 16), increasing the tone of voice, giving orders (Excerpt 17), sounding dismissive, and not listening (Excerpt 19). Increasing the tone of voice was considered an old model of leadership practice connected to authoritarianism, reducing their psychological safety and sense of control (Excerpt 18). Giving orders is considered an ineffective way of communication since it suggests inequality among the team members, and participants considered it to be disrespectful and caused them feelings of unsafety:

Excerpt 16: “Imposing your view is not working and is good for no one.”(Mary)

Excerpt 17: “I found myself to act badly every time I spoke more loudly.”(Michael)

Excerpt 18: “Telling the team what to do and being like do this and do that made me feel insecure.”(Christine)

Excerpt 19: “If you are not listening to the team then you are a bad leader.”(Helen)

The two sub-themes function supplementary, as the positive and negative qualities discussed by the participants could almost be described as “polar opposites”, meaning a leader that leads via safety could be the opposite of the leader who leads via fear. Both psychological safety and a sense of control are important structures that enable actions and behaviors. Psychological safety and sense of control are in a reciprocal relationship; when the participants feel safer, they feel they can be more in control. When the participants are more in control, they feel more psychologically safe. From a leadership development perspective, it is more likely for young people to behave as good leaders when mechanisms that enable a stronger sense of psychological safety and control are activated.

Theme 4: Facilitation of leadership development at a young age.

Within their interviews, participants discussed potential facilitators of leadership development. These emerged in two sub-themes: facilitation related to nurture from the close environment and facilitation via focused leadership training.

Sub-theme 1: Leadership skills nurtured by the close environment.

Here the participants reflect retrospectively on forces that at the present they believe can help a young person shape their leadership development since early childhood and during their adolescent years. According to participants, facilitators related to nurture include parents, teachers and extracurricular activities; as discussed in Excerpt 20, parents act as role models to their kids since they provide them with opportunities to take up leadership roles and support them.

Excerpt 20: “My mum has helped me mostly, my family overall…this is a main factor that helps you develop leadership. (…) I went camping, and I wanted to leave, but my mum did not let me. I stayed for a month alone with the other kids, she came to visit but contrary to other mums that took their children back home when they were crying, she explained…. At that point, I realized that I had to change some things, and I found my strength.”(Mary)

Teachers that are engaged in their role were reported as role models that showed them the way to believe in themselves and that was beneficial to the participants since that gave them the confidence to believe in themselves and take up leadership roles (Excerpt 21).

Excerpt 21: “A teacher has been really inspiring to my development. He helped me believe in myself and always try for the best, not to give up.”(John)

The interactions some of the participants had with their peers and with their tutors as part of their involvement in extracurricular activities (e.g., scouts; Excerpt 22) were identified as very meaningful as well, highlighting skills that have been previously identified as those that make a good leader (Theme 3, sub-theme 1):

Excerpt 22: “Being in scouts from a young age helped me learn to interact with others. They were giving us feedback to learn to communicate effectively, not impose our opinion but learn to discuss with the team and listen to the others.”

This sub-theme refers to facilitators that the participants have identified in retrospection of their experiences during their upbringing as children and adolescents; they are not hypothetical scenarios neither speculation; they are rather empirical reflections of the participants of what they, in retrospection, believe has helped them in their leadership development so far.

Sub-theme 2: Acquiring leadership skills via focused training.

Within their interviews, participants discussed how targeted trainings and programmes for developing leadership skills can help young adolescents become better leaders. According to the participants, leadership skills can be taught, and this sub-theme was mostly generated from the participants’ retrospective reflections and perceptions.

Excerpt 23: “Yes, sure, I believe we can [teach leadership skills] (…) it can be taught through experiences, through people you are interacting with…”(Kate)

Excerpt 24: “Yes, with a particular timeline, with a particular programme because this is something very important that cannot be communicated via a course in the classroom or in the university. With a particular programme for a number of years, during a time period, some things can be taught.”(Sophie)

Experiential learning emerged as a pattern in the interview transcripts as follows: leadership “can be taught through experiences” (Excerpt 23); “cannot be communicated via a course in the classroom or in the university” (Excerpt 24); “For children, they must experience it and take upon a leadership role” (Excerpt 25); “I think that a leadership programme… must be experiential” (Excerpt 26); “many workshops that simulate certain situations” (Excerpt 27).

Excerpt 25: “You cannot teach leadership the same way that you teach maths in a direct way … it is something that we have to experience. For children, they must experience it and take upon a leadership role, see it in action and step-by-step practice in order to transfer the skills in real life…”(Steve)

Excerpt 26: “I think that a leadership programme (…) must be experiential … in a leadership development programme (…). To manage a team in difficult circumstances in an unsafe environment must definitely be a part of the programme…”.(Ann)

Excerpt 27: “Activities that will develop leadership so workshops, many workshops that simulate certain situations in which participants will have to make certain decisions, to form groups. Through groups, they need to make something together.”(Mary)

Participants understand the complexities and the difficulties of teaching leadership skills to children and adolescents; they have been adolescents themselves recently, and potentially now that they are young adults experiencing leadership positions, they are more aware of how complicated “teaching” leadership can be. They all seem to agree, however, that the best way to teach leadership is by providing adolescents and children with opportunities of experiencing leadership first-hand. On a more implicit level, the participants’ accounts indicate that traditional teaching and schooling/university education does not promote or allow them to engage in opportunities to develop leadership skills. Leadership training is seen and experiences as something active, engaging, interactive, experiential and practical, as opposed to the more passive and cognitively inclined school/university education. Table 3 presents a summary of all themes and sub-themes that emerged in the analysis.

Table 3.

Themes and sub-themes that emerged from the analysis.

3. Study 2

3.1. Research Questions

The purpose of Study 2 was to examine the experiences of adolescent participants attending a leadership programme. Study 1 was a necessary first step in building an understanding of how young leaders experience leadership. Prior to exploring leadership among adolescents, it was beneficial to identify themes and asses the most appropriate methodology to use in collecting leadership data from adolescents. The analysis of themes from Study 1 indicated that leadership was experienced as a form of facilitation that was developed on a trial-and-error basis daily with safety and control being identified as important mechanisms in promoting good leadership. Thus, it was obvious that a more dynamic methodology (i.e., diaries) was needed to explore how taking on a leadership role was experienced on a day-to-day basis (e.g., with peers/friends, family or at school) among adolescents while attending a leadership development program. More specifically, in Study 2, the research conducted aimed at answering two research questions that have been developed to illuminate their experiences of developing leadership skills via attending a leadership programme. We focused specifically on memorable incidents while attending the programme, and the application of leadership skills in their school and/or personal lives. The questions were formulated as follows:

- In what ways did the experiences of the programme transfer to the school life and non-school life of the participants?

- What were the main elements of the programme that were identified as important for the transferability of the learned skills?

3.2. Materials and Methods

3.2.1. Design

A qualitative study involving data collection with diaries was conducted. The epistemological, ontological and analytical approach of Study 1 was also applied in Study 2.

3.2.2. Participants

The study sample consisted of 20 Greek adolescent students attending a leadership programme that was held at the University of Macedonia, Greece and was designed to enrich students’ leadership skills. Purposive sampling was applied. The authors of the article were involved in the programme as tutors. The programme aimed to train students in leadership skills that include communication skills, problem-solving, teamwork and self-awareness. The sample consisted of 11 girls and 9 boys aged 12–16 years old, and the mean age of the sample was 13.75 years. Everyone who participated in the programme was included in the research, and the selection criteria for their participation in the programme were their age (between 12–16 years old), knowledge on English language (due to the program being bilingual, see Section 3.2.3) and their personal interest in attending the programme.

3.2.3. Description of the Programme

The leadership training programme aimed to develop the students’ ability to cooperate in a team, and demonstrate effective communication skills, public speaking skills, critical thinking and self-awareness. The programme is addressed to adolescents in the age range of 12 to 16 years and the duration of the programme is nineteen weeks, and each course lasts for 2.5 h. The programme is bilingual in Greek and English. Students developed their leadership skills through role-playing, presenting seminars to others, public speaking at events and management of groups. Students were encouraged to develop an approach that would inspire them and provide them with motives to work with others, considering the needs and characteristics of the members of the group. The students participated in public action events (e.g., creating a new political party and communicating their vision to the media) twice during the course.

The programme is guided by principles from action research, meaning that the process of the programme is structured to allow the participants to drive the content and activities. In this way, the programme tries to avoid participants taking a passive student’s role. There were multiple small group activities that assigned students to different groups to share the benefits of the programme with the other members. Small group sessions that required reflection, sharing ideas, solving problems, and networking in a collaborative, supportive environment and students engaged in self-reflection, self-discovery, and discussion through weekly challenges and reflective worksheets and activities. Throughout the sessions, students learned about leadership characteristics and qualities and knowledge of group dynamics and teamwork. They were encouraged to develop their personal leadership style and how they could distinguish themselves as a leader.

3.2.4. Data Collection

For this study, data was collected via weekly diary entries. Through the diary approach there is the opportunity of capturing the dynamic picture of adolescents’ memorable experiences when attending a leadership development programme providing detailed descriptions. Within the social sciences, a diary approach is commonly used in clinical and educational contexts to evaluate human behavior, as well as the process and content outcomes in educational settings [27]. Previous studies have used diaries as an evaluation strategy to examine education/training effectiveness, the perceptions and feelings of the studens’/trainees’ and the perceived benefits [28,29]. Diary studies, which assess within subject experiences, offer the opportunity to collect rich data and allow us to study the frequency of “critical incidents”. Critical incidents (or memorable incidents) represent the point at which important information is revealed as to what attitudes and behaviors are valorized [30]. Critical/Memorable incidents analysis collected in the form of short narratives of incidents that the students judged to be important and relevant to their learning experiences is a well-suited method that can provide in-depth information on the impact of conflicting experiences in students [31]. Recording critical incidents positions the students in situations that allow reflection upon experiences that facilitate personal growth [32], which in turn allows the researchers to access those experiences and the meaning the participants have attributed to these experiences.

The recommendations of Bolger, Davis and Rafaeli [33] were taken into account when designing the diaries. As such, (1) diaries were designed to be portable and pocket-size, (2) the diary format was pilot-tested, (3) ongoing contact with participants was maintained, and (4) the difficulty in filling out diaries was communicated to participants and individuals were prompted to exclude their diary if they believed that they had not filled it in adequately. All diaries were anonymized, transcribed and archived electronically in a database to which both researchers could have access. Two researchers independently analyzed the data using RTA as described previously and compared their results. The independently generated themes were reviewed by the two researchers and a final agreement was reached. At the end of each weekly course, participants received a hard copy of the weekly diary and returned it completed at the next course. If a student was absent, they did not receive a diary. For each week, the individuals were asked to fill in the diaries by answering the following questions:

- (1)

- Thinking back on last week did anything happen in school or out of school where you thought what you learned at the programme was useful?

- (2)

- What specifically was it that you learned in the programme, and how was it useful?

- (3)

- What skills did the programme help you develop, and how are you using these skills?

Finally, the participants were asked whether they discussed the programme with other people. The students completed the diary at home and were advised to write it the day before the course so that they would include the experiences and incidents of the week that passed. They received a reminder message on their mobile phone one day before the course so that they would remember to fill in the diary case they had forgotten to write it.

3.2.5. Data Analysis

Data collected via the diaries was analyzed with the use of RTA [15], as in Study 1.

3.2.6. Ethical Considerations

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their participation in the study, and in the case of adolescents (under 18 years old), informed consent was obtained from the parents as well. Historically, data obtained from children have been viewed as unreliable and invalid because it was believed that children were too immature to understand their worlds and lacked the necessary verbal and conceptual abilities to convey their experiences [34]. Our modern approach is that, as with adult participants, children’s and adolescents’ accounts have their own validity in terms of their perspective on how the world appears to them [35]. Globally, there has been a growing recognition of children’s rights, particularly in relation to their involvement in decision-making as a result of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [36]. Finally, reflexivity is seen as another means of managing the culture gap and enabling adult researchers to be aware of their own assumptions about childhood and how this may influence the research process and their understanding of those they study [37]. Ethical considerations and institutional approval as described in Study 1 apply for Study 2 as well.

3.2.7. Reflexivity Statement

The authors (DK, AM) have been actively involved in leadership trainings for adolescents and young adults prior to and during the time the study was conducted. During the data collection (DK) and data analysis stages (DK, OL), two authors (DK, AM) were tutors on the leadership programme, having knowledge of the curriculum and the aims. Thus, two authors (DK, AM) were acquainted with the participants of the study prior to recruitment, as the participants were students in the programme. The authors involved in data collection (DK) and analysis (DK, OL) engaged in reflexivity (reflexivity diary logs) to identify potential sources of researcher bias. The authors’ knowledge of the program aims as well as the relationships with the participants due to being students (DK), have been identified as potential sources of bias.

3.3. Analysis

In total, 217 diaries were returned and analyzed. None of the participants provided feedback for all 19 weeks. The average number of weeks that the participants filled their diaries was 11 weeks; 90% of the participants answered all four questions, and the mean number of sentences over the 19 weeks was six. Participants filled in the date and time they filled the diary, and they followed the same schedule each week for the completion of the diary, mostly in the evening hours. A total of 87 meaningful units—diary entries that consisted of excerpts that were analyzable—were analyzed. Participants reported that they had acquired competencies through their participation in the programme at both the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels.

Axis 1. Empirically observed skills

Theme 1: Developing interpersonal skills.

Students reported acquiring interpersonal skills that helped them effectively interact with their peers in the programme and also applied them in their everyday life.

Teamwork skills were mentioned multiple times by the participants, who reported that they use collaboration skills a lot in their everyday lives and mostly at school. Being able to work effectively in different group combinations was mentioned by all the participants (e.g., Table 4, Excerpts 1). Participants mentioned the team as an important factor in their development and the interaction they had with their peers in the programme (Table 4, Excerpts 2,3,4,5).

Table 4.

Excerpts for Study 2.

Participants reported developing emotional regulation skills that included the awareness and management of their emotions and their empathy towards others. According to the majority of the participants realizing and managing their emotions helped them in their everyday interaction with others. The majority of participants highlighted the importance of their emotional awareness since they were able to understand and distinguish their emotions. Before the programme, they mentioned that they felt difficulty recognizing their emotions. Emotional awareness was mentioned several times (e.g., Table 4, Excerpt 6), as well as emotion management, which was connected mostly with the management of their fear, anger and stress (e.g., Table 4, Excerpt 7). Being able to understand the emotions of others and, through this, being able to accept them and see their viewpoints was highly mentioned by the majority of students, suggesting empathy as one of the skills that were developed (e.g., Table 4, Excerpt 8).

Theme 2: Cognitive Skills.

Cognitive skills involve decision-making, problem-solving, critical thinking and persuasion. Participants highlighted the importance of understanding the process of making a decision, solving a problem and using their critical thinking.

Participants reported acquiring decision-making processes both as individuals as well as a member of a team. Decision-making was mentioned several times by the participants and often was linked with time management since in most activities they had to make decisions in a specific amount of time (e.g., Table 4, Excerpt 9), as well as problem-solving skills (Table 4, Excerpts 10 and 11).

Theme 3: Self-Development.

All students reported that they understood differently many aspects of themselves that they were not aware of (e.g., their sociability) and that that helped them since they better knew their strengths and weaknesses and they linked those skills to their leader identity. As one student said, ‘Knowing who I am I can find my leadership style better’. Within their self-development, they included self-evaluation, self-confidence and public speaking (Table 4, Excerpts 12, 13, 14).

Theme 4: “Learning” leadership skills.

Participants reported enhancing skills and knowledge due to their participation in the programme regarding leadership and some factors that acted as facilitators to this process. The factors could be categorized into three categories: exposure to leadership behaviors, safe environment and relational aspects.

Through their interaction with their peers, they could see and learn from the different approaches and styles that their classmates had and be inspired (Table 4, Excerpts 16 and 17).

Participants reported that the new information they gained every week helped them in their own process of identifying their leadership identity, and they often considered them as ‘life lessons’ that encouraged them to find new ways to look at established things (Table 4, Excerpts 17 and 18). In addition, the participants highlighted the need for facilitators in order for the students to explore their potential. Safety from their tutors and classmates enhanced their sense of comfort, and they could actively listen to their classmates and speak their views. Tutors were reported by the participants as a safety net that they could rely on, and they felt they could trust them and act without fear or stress (e.g., Table 4, Excerpt 19). Moreover, they mentioned they could reflect after the course and discuss it with their family and compare it with school, which they did not discuss with their family. Participants reported that physically moving in the classroom acted as a facilitator for them since they felt free (e.g., Table 4, Excerpt 20).

Axis 2. A critical realism approach to the mechanisms underpinning the development and transferability of leadership skills through the critical/memorable incidents.

Participants reported a variety of incidents in which they exhibited and applied the skills they were exposed to during the programme. The incidents described in the diaries indicate that participants utilized the experiences from the course in their everyday life, mostly within the school context and within their interpersonal relationships and interactions with others. Teamwork was mentioned on 26 occasions, public speaking on 25, critical thinking on 22, communication on 17, and decision-making on 15. The settings where incidents took place were; the school, home and outdoor activities (Table 5 see excerpts). In total, 62 unique incidents of leadership behavior were described by the students. The incidents focused on the interaction with others and the reflection the participants had on them.

Table 5.

Examples of Critical/Memorable Incidents (Excerpts) involving mechanisms for transferability (Mechanisms—real domain) of leadership skills (Skills—empirical domain).

The critical/memorable incidents consisted of situations where the participants perceived they managed to transfer skills they developed in the leadership programme to real-life situations in school life and non-school-life (e.g., relationships with friends and extracurricular projects). In that sense, diaries serve a reflective function in the learning process, influencing the experienced outcomes of the programme for the participants and potentially the transferability of the learned skills.

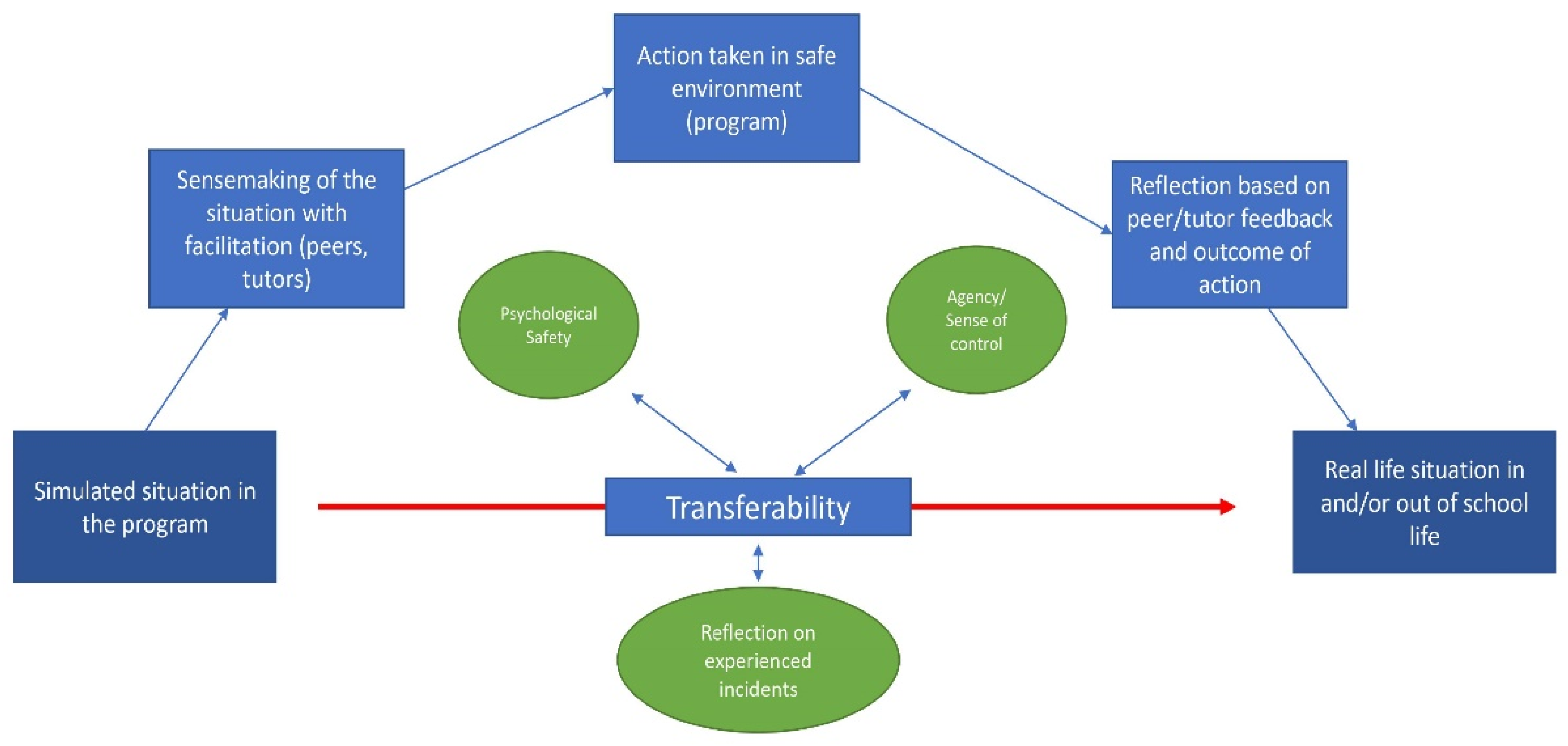

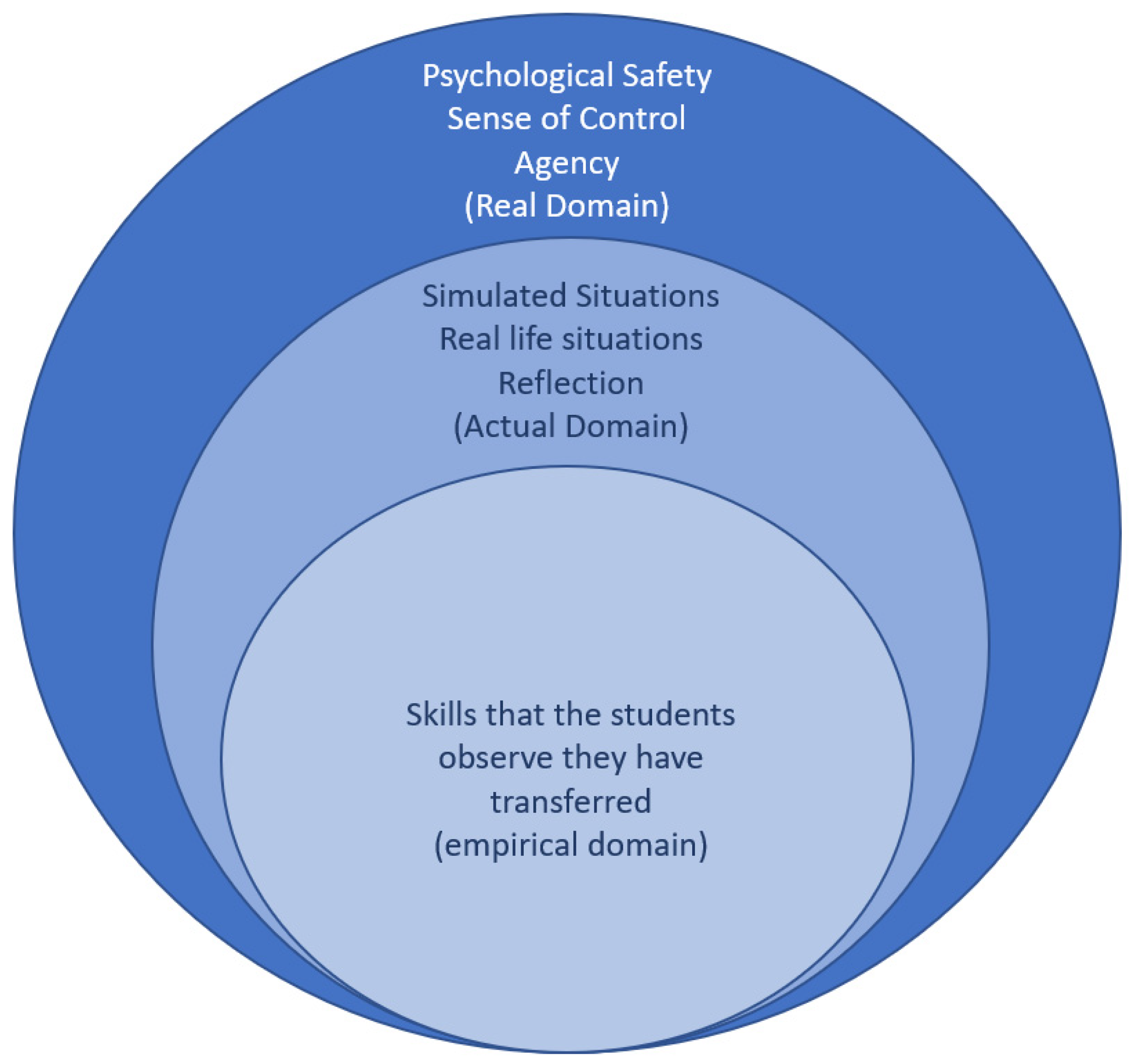

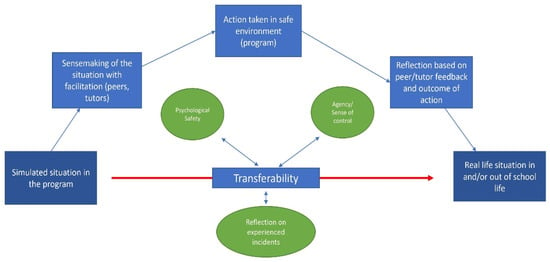

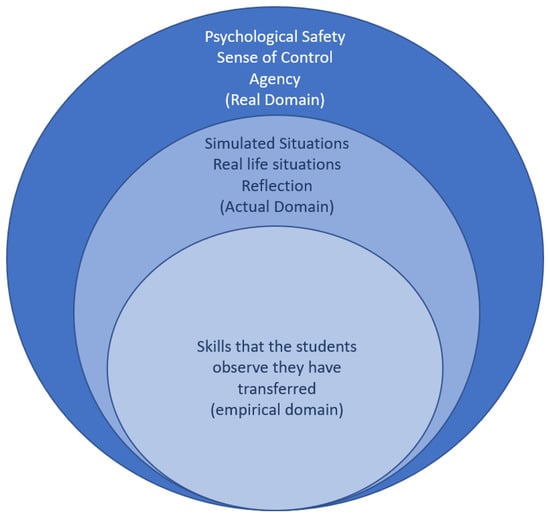

The overall analysis can be best understood by considering Figure 1 and Figure 2 in parallel, which depicts a pathway of how transferability works as experienced by the participants (see Figure 1) and presents the layers of reality as suggested by the critical realist approach (see Figure 2). Taking this into account, the analysis of the incidents generated patterns that are related to the skills that the participants observed themselves (see Table 5, empirical domain). These were generated on the level of semantic focus and are related to the empirical domain of observable experiences; thus, those themes reflect what the participants themselves perceived they have learned in the programme and managed to transfer to real-life situations. On a latent-focus level, the analysis generated two main themes that are related to the hidden mechanisms (see Table 5, mechanisms—real domain) that have generated the actual events—the examples of “transferability” of the learnt skills. Following this analysis, psychological safety and sense of control/agency are the two mechanisms that have generated the actual events. In that sense, when the participants do not feel psychologically unsafe, the sense of control is unstable and thus, agency is inhibited. These mechanisms belong in the real domain (see Figure 2) and have ontingent causal forces to generate or stop actual events. Thus, when the participants feel more psychological safety is low, they are more likely to engage in actual situations that occur in a safe environment, with peer and tutor facilitation (see Figure 1). This will increase the perceived sense of control over the situation and will also allow the participants to act on the situation. This mechanism of sense of control/agency will generate the event in the actual domain and will lead to the experience; the students will reflect upon the skills they feel they have used based on their experience, as well as peer and tutor feedback (see Figure 1, Reflection based on…action). As the participants feel more psychologically safe, the sense of control increases and is expressed via agency; thus, outside of the programme this time, they attempt to transfer skills from the programme to real-life situations. Diaries helped the participants reflect on the experience. The red arrow (Figure 1, Transferability) is a representation of transferability over time, repetitive exposure and reflection. This does not indicate a linear causal relationship between simulated situations and real-life situations; it is a model of contingency causality; and potentially a feedback loop.

Figure 1.

Graphical depiction of the analysis of memorable incidents.

Figure 2.

Critical realist depiction of the proposed model.

4. General Discussion

The overall aim of this research was to investigate how leadership can be studied among adolescents and young adults and how they conceptualize and experience leadership. This research addresses a significant gap in the literature—that of leadership being a well-studied phenomenon in adults but not in adolescents. We identified core elements of leadership development in adolescents using a qualitative approach and added to the literature on youth leadership by examining the phenomenon using interviews and diaries. More specifically, the research has explored the meaning of leadership and examined the perspective of adolescents and young adults with regard to the concept and experience of leadership.

Through the interviews in Study 1, participants shared experiences where they explained how they view themselves as leaders. When sharing their perceptions of leadership (Theme 1), participants significantly relied on how potential leaders make other people feel; thus, when discussing leadership as an abstract notion, most of the participants positioned themselves as potential “followers” or “team members” and implicitly reflected on how they want a leader to make them feel. When sharing their perceptions on how they view themselves as leaders (Theme 2), participants significantly relied on experiences where interacting with other people has made them feel competent and validated as leaders; in this case, they reflect on the issue being positioned as leaders. From a leadership development perspective, this could mean that young people rely on how other people make them feel both when positioned as followers and as leaders; external validation of their leadership role is a generative mechanism that enables or constrains their actions, regardless of whether they are a team member/follower or a leader. Regardless of that, however, they seem to give equal importance to psychological safety and a sense of control (Theme 3, sub-theme 1) and are against behaviors and attitudes that are affiliated with authoritarian leadership models (Theme 3, sub-theme 2). This can be reinforced by the facilitators of leadership development they reflect upon (Theme 4, sub-theme 1): parents, teachers and childhood extracurricular activities, while they are in favor of organized leadership trainings where children and adolescents can experience leadership roles in settings of psychological safety and sense of control (Theme 4, sub-theme 2).

Study 2 explored the experiences of adolescents in a leadership training programme. Twenty students completed diaries over a six-month period. The interactions that participants reported in the programme with each other acted as a milestone to their empowerment of their self-awareness. The critical incidents indicated how a safe environment allowed them to explore their leadership potential and transfer skills beyond the programme. Participants reported that they gained confidence as leaders in the areas of teamwork, communication and public speaking and were better able to manage and regulate their emotions.

Adolescents are in this developmental-sensitive period in their lives where cognitive, social and emotional changes occur. The safety of their learning environment and the trusting relationships with their tutors are important to them [38]. Even though research with adults shows that psychological safety is important, psychological safety in adolescents might be qualitatively different and heavily influenced by peer acceptance. A person’s emotional condition affects the physiological procedures of learning, where more in-depth and permanent learning happens when all areas of the brain are used, including the emotional center [39]. However, in adults, psychological safety leads to increased learning, particularly in groups with hierarchical membership [40], adolescents’ attitudes, values, and behaviors are influenced by their peers and by peer leaders, and can have a very powerful impact on both positive and negative behaviors [41]; thus, among adolescents, psychological safety might be affected more by peer support and approval compared to adults.

Utilizing Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development [42], adults reach full moral development when they answer to an inner conscience, adhering to a small number of abstract principles that produce specific rules. In that sense, if a leader is defined as a person who inspires and motivates other people towards achieving their own goals, then, when reflecting on the self as a leader, an adult is expected to draw upon experiences where they inspired and motivated other people to achieve their goals. Additionally, although the theory of Kohlberg [42] suggests that approximately only 15% of adults reach that stage of moral development and there is very limited objective evidence on how moral adults really are, the majority of adult leadership models that are being currently endorsed and highly valued (transformational leadership; ethical leadership; authentic leadership; servant leadership) are based on the assumption that all people reach the “universal ethical principle” [42] or at least on Kant’s [43] idea about “the natural predisposition of good”. Meanwhile, research evidence indicates that toxic leadership and abusive supervision prevails among different settings [44]. Thus, this highlights how leadership development in adolescence can potentially be a critical period to promote moral development, and this can be better achieved in environments that are experienced as psychologically safe and provide adolescents with a stable sense of control. In essence, we need to provide adolescents with a “trial-and-error” environment.

Sensemaking provides a useful way to understand how young adolescents actively conceptualize their ideas about leadership [45], as evidenced by the data in the two studies. Sensemaking, with its focus on how meaning influences action, also provides a way to understand the evolution of adolescents’ thinking about themselves as leaders. Sensemaking is not about truth and “getting it right” but about the way people develop their own narratives. Firstly, it is about the continued redrafting of an emerging story so that it becomes more comprehensive, incorporates more of the observed data, and is more resilient in the face of criticism [45]. Secondly, the language of sensemaking captures the realities of agency, flow, equivocality, transience, accomplishment, unfolding and emergence—realities that are often obscured by the language of variables, nouns, quantities and structures [45]. The efforts of the adolescents (Study 2) and young adults (Study 1) to make sense of leadership complement the contradictions they experience in trying to figure out leadership as an action from a context in that their experiences highlight a more authentic and service-based form of leadership.

We need a bespoke model of leadership for younger people. However, we can still appreciate the way that more traditional approaches are reflected in the behavior of adolescents and young adults. The findings suggest that various leadership theories are expressed in participants’ leadership behavior. The transformational leadership approach appears to be opposed to the old model of formal, one-person leadership, as it focuses on the relational, collective and purposeful interactions [46,47], where leaders do not impose authority and control but acknowledge the significance of their followers. The model focuses on principles of teamwork, collaboration and communication.

The research highlighted the importance of adolescence as a developmental stage for the development of leadership behavior. Adolescents who had taken part in a wide range of activities stated having been exposed to more leadership opportunities and an active role in decision-making procedures [48]. A safe environment with empathy and acceptance on behalf of the adults who empower the adolescents’ self-confidence has a significant positive contribution to their leadership identity. Rogers [49] has studied the role of empathy within the leader role, and the ability to have empathy can be taught with practice. Establishing trusting relationships with their tutors and peers was highlighted in this research, where participants’ basic needs of safety were met [50]. Where the willingness to collaborate is low, so is trust, and people will opt to work from a self-interest perspective rather than work for the interests of the whole group [51].

This research highlighted that while youth perceptions of their leadership skills are developed upon a variety of factors, they are also heavily informed by their own experiences and sensemaking. Tutors need to find ways, such as youth-adult partnerships, to involve parents and other adults in extracurricular activities. Support from parents, teachers and other adults has a significant role in developing leadership skills. Adolescents who sense that significant adults have an active interest in their development rate themselves more highly in their leadership skills and their willingness to undertake leadership roles [52]. The importance of role models as well as the importance of peer support in a safe environment, was underscored in this research.

4.1. Implications for Future Research

Our research leads to important questions that future studies should address. Further research could expand our approach to studying the experiences of primary school students and explore the issues in these younger children, which could shed light on how younger children conceptualize leadership. Involving data from parents and teachers in research would provide researchers with an enhanced idea of leadership development among adolescents. At the moment, we are not aware of any comprehensive model or theory of leadership that adequately reflects students’ perspectives. Teaching leadership in schools could have multiplier benefits for students in terms of their career development. Mitra [53] suggests that students who attend a school where they are empowered by school administrators to share their voices are more likely to develop as leaders. Likewise, we would expect that mentoring relationships with teachers and faculty advisors should enhance future leadership development [54]. Research has found that the more students are involved in student organizations and leadership programmes, for example, the more likely they are to develop the leadership skills needed later in their working lives [55].

4.2. Practical Implications: Developing Future Leadership Programmes for Adolescents

The findings in this research indicate the positive impact of leadership opportunities and training during adolescence. Henein and Morisette [56] highlight their priorities for the field of education, which include the creation of core leadership educational materials provided to students at all levels in all areas, adjusted to age level. A predominant principle for those included in positive youth development is that adolescents should be agents of their own development and, thus, in control of the benefits of these opportunities [57]. Therefore, as youth are enabled to participate in programmes with more levels of voice, empowerment, and contribution, youth are more expected to become engaged in the programme. Hansen and Larson [58] found that youth benefit developmentally from these types of programmes when they are engaged in leadership roles.

The findings of tour research suggest that experiential activities were experienced the most effective learning method for the leadership qualities that could be taught. Furthermore, the importance of peer learning as a means of applying leadership was emphasized. The natural human desire to help others is based on the belief that when a person gives and becomes valuable to others, feelings of self-worth are increased, and a more positive self-concept is built. The powerful feeling of being engaged in ‘something beyond oneself’ can be transferred to ones’ peers. When adolescents’ contributions to helping others are acknowledged, meaning and purposefulness become more important [59].

4.3. Limitations

Alongside the strengths of this research, there are also important limitations to acknowledge. Firstly, all data are based on participants’ accounts and represent a single source about their experience of leadership. For example, interviewing their teachers and/or their school colleagues could have provided an interesting perspective on the genesis of their development as leaders (study 1) and their experience of leadership within the school environment (study 2). Secondly, study 2 was conducted in one single leadership programme, making the generalizability and transferability of findings limited. Furthermore, when analyzing qualitative data, the influence of the researcher is something to consider, given that the process of interpretation can be subjective.

The scope of this research was the investigation of the experiences of adolescent leadership using a qualitative approach. However, it is important to recognize that other research approaches to youth leadership exist in the literature, and therefore there are constructs that were not covered in the two studies. For example, personality research across the lifespan indicates that leadership is associated with personality traits such as extraversion, sociability, and gregariousness [60,61,62]. Additionally, at the very beginning of life, conceptualizations of leadership begin to form [63,64], which means that children probably build implicit theories of leadership that contain expectations about leadership traits and attributes [65]. Equally, in the area of attachment theory, there is evidence that secure attachment in infancy is associated with leadership ratings 15 years later [66]. One possible explanation is that individuals with secure attachment at early ages have more ego resources or social capital for seeking out leadership roles [67,68]. Examining the developmental journey of adolescent leaders was beyond the scope of the two studies, but such factors may contribute to how the participants in the present research understood leadership development.

Future research on youth leadership could utilize Bronfenbrenner’s [69] Ecological Systems Theory, which highlights the role that environmental forces play in initially shaping one’s identity and modifying it throughout life through constant interactions with environmental factors. We need a lifespan approach to leadership development. Individuals at each developmental stage have opportunities to work on their leadership development and acknowledging the long developmental trajectory that underlies effective leadership can only enhance our knowledge of more effective ways to develop leaders for the challenges of the future [70]. The next steps in furthering this research involve testing our model among a broader group and developing links between our model and adult models of leadership.

5. Conclusions

Leadership continues to be a complex topic [71,72,73]. Understanding leadership development in children and youth is an important step in the process of improving and developing effective leadership education. This research highlighted the importance of adolescence as a developmental stage for the development of leadership behavior. Participants’ experiences highlighted the importance of active and experiential learning, and a safe environment was reported as a significant facilitator in the participants’ leadership development as they felt accepted by their tutors and peers.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: D.K. and A.M.; data collection: D.K.; analysis and interpretation of results: O.L. and D.K.; draft manuscript preparation: D.K., O.L. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the University of Macedonia.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to the data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gottfried, A.E.; Gottfried, A.W.; Reichard, R.J.; Guerin, D.W.; Oliver, P.H.; Riggio, R.E. Motivational roots of leadership: A longitudinal study from childhood through adulthood. Longitud. Stud. Leadersh. Dev. 2011, 22, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagianni, D.; Montgomery, A. Developing leadership skills among adolescents and young adults: A review of leadership programmes. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2017, 23, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gest, S.D.; Graham-Bermann, S.A.; Hartup, W.W. Peer experience: Common and unique features of number of friendships, social network centrality, and sociometric status. Soc. Dev. 2001, 10, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Steinberg, L. (Eds.) Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, Volume 1: Individual Bases of Adolescent Development; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.; Holden, E.; Collyns, D.; Standaert, M.; Kassam, A. The Young People Taking Their Countries to Court over Climate Inaction. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/may/07/the-young-people-taking-their-countries-to-court-over-climate-inaction (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Terenzini, P.T.; Pascarella, E.T.; Blimling, G.S. Students’ Out-of-Class Experiences and the Influence of Learning and Cognitive Development: A Literature Review. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 1996, 37, 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Shook, J.L.; Keup, J.R. The benefits of peer leader programs: An overview from the literature. New Dir. High. Educ. 2012, 2012, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.C. Conducting semi-structured interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 492–505. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R. The Possibility of Naturalism, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bygstad, B.; Munkvold, B.E. Search of Mechanisms. Conducting a Critical Realist Data Analysis; ICIS: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.L. Testable theory development for small-N studies: Critical realism and middlerange theory. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Syst. Approach 2010, 3, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J.D.; Yoho, S.K. Toward a Contingency Model of Leadership and Psychological Empowerment: When Should Self-Leadership Be Encouraged? J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2005, 11, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Cox, J.; Sims, H.P., Jr. The forgotten follower: A contingency model of leadership and follower self-leadership. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport. Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Iosifides, T. Qualitative Migration Research: Some New Reflections Six Years Later. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 6th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. (Mis) conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with Fugard and Potts’(2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2016, 19, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidder, L.H.; Fine, M. Qualitative and quantitative methods: When stories converge. New Dir. Program Eval. 1987, 35, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.A.; Orr, E.; Durepos, P.; Nguyen, L.; Li, L.; Whitmore, C.; Jack, S.M. Reflexive thematic analysis for applied qualitative health research. Qual. Rep. 2021, 26, 2011–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jongh, J.C.; Wegner, L.; Struthers, P. Developing capacity amongst adolescents attending a leadership camp. S. Afr. J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 44, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill, A.; Deans, C.L.; Chapin, L.A. Pre-leadership processes in leadership training for adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 88, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.M.; Namey, E.E. Introduction to applied thematic analysis. Appl. Themat. Anal. 2012, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, A.D.; Bartini, M. An empirical comparison of methods of sampling aggression and victimization in school settings. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 92, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, B.; Wiese, B.S. New perspectives for evaluation of training sessions in self-regulated learning: Time-series analyzes of diary data. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 31, 64–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L. Using Students’ Weekly Diaries to Evaluate Positive Youth Development Programs: Are Findings Based on Multiple Studies Consistent? Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 95, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, D.W.; Corbie-Smith, G.; Branch, J.; William, T. “What’s Important to You?”: The Use of Narratives To Promote Self-Reflection and To Understand the Experiences of Medical Residents. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002, 137, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.; Doulougeri, K.; Panagopoulou, E. Do critical incidents lead to critical reflection among medical students? Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2021, 9, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, N.; Davis, A.; Rafaeli, E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, S.; Sandelowski, M. Focus on qualitative methods: Interviewing children. Res. Nurs. Health 1999, 22, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]