Fruit Vending Machines as a Means of Contactless Purchase: Exploring Factors Determining US Consumers’ Willingness to Try, Buy and Pay a Price Premium for Fruit from a Vending Machine during the Coronavirus Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Pandemic Food Shopping and Pandemic-Related Benefits of Fruit Vending Machines (FVM)

2.2. Importance of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Fruit Attributes

2.3. FVM Benefits

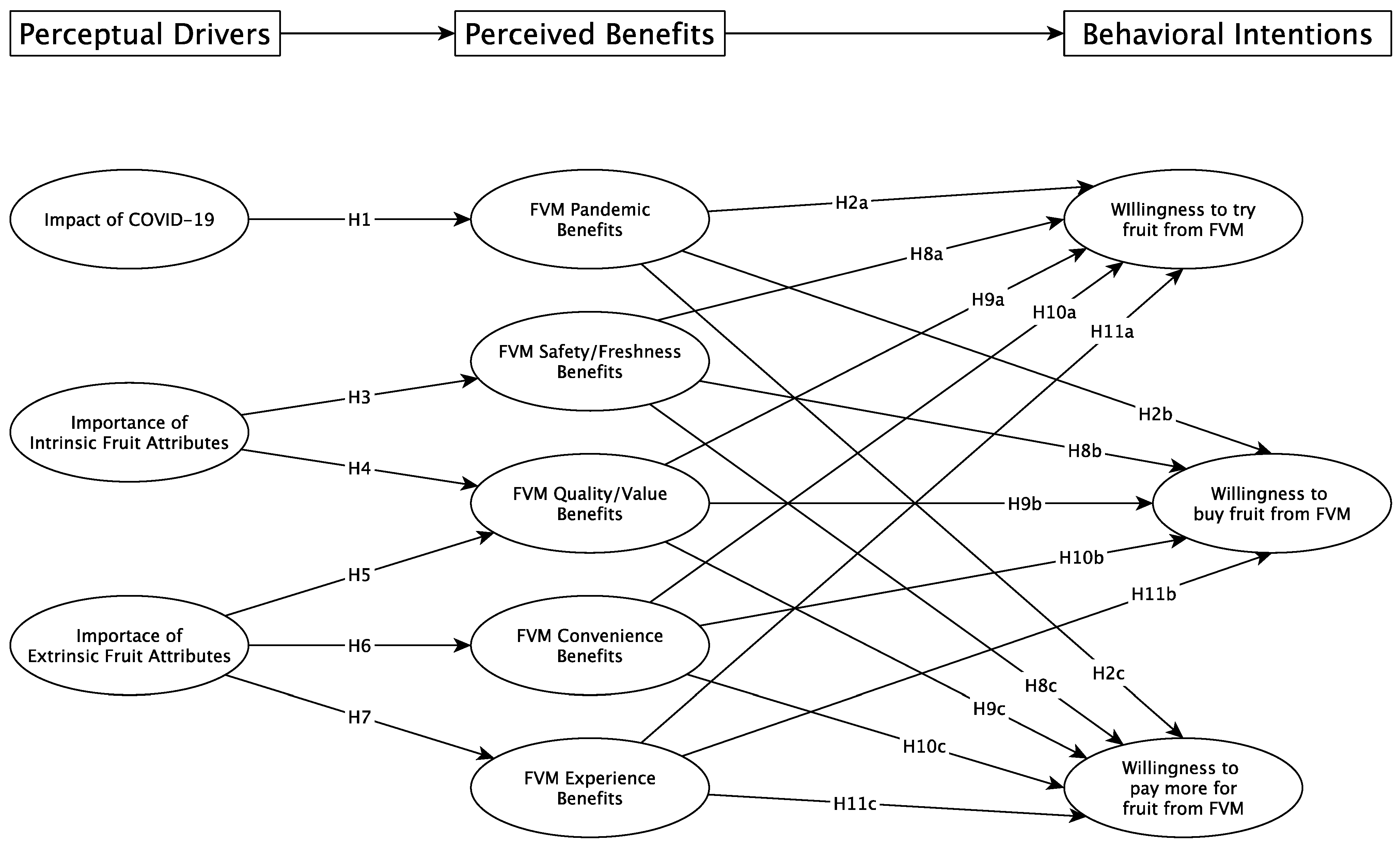

2.4. Conceptual Model

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Research Approach and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Description

4.2. Measurement Model

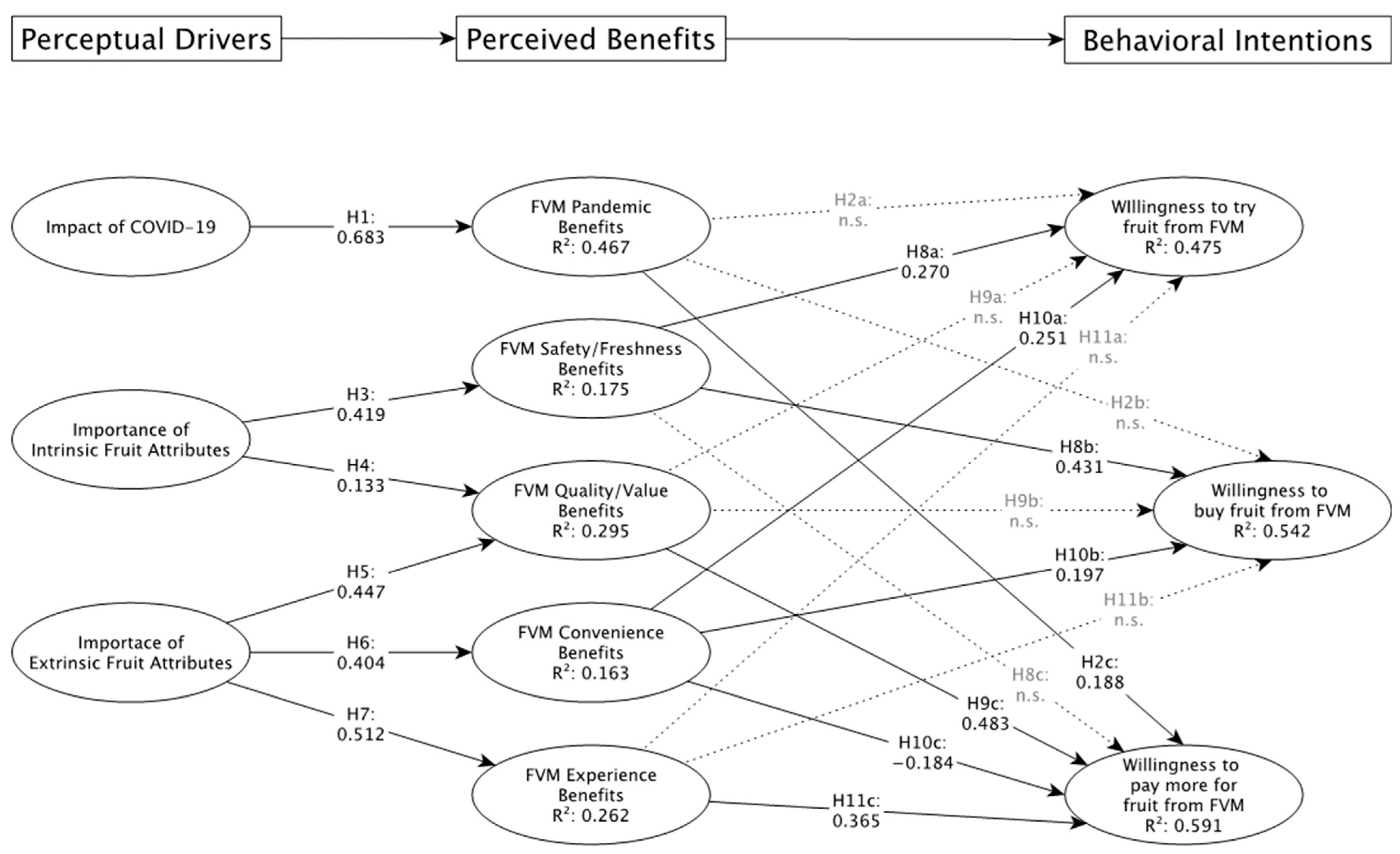

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. Results from the Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications and Suggestions for Future Research

6.2. Information for Practitioners

6.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashour, H.M.; Elkhatib, W.F.; Rahman, M.M.; Elshabrawy, H.A. Insights into the Recent 2019 Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in Light of Past Human Coronavirus Outbreaks. Pathogens 2020, 9, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, R.; Pei, S.; Yin, C.; He, R.L.; Yau, S.S.-T. Analysis of the Hosts and Transmission Paths of SARS-CoV-2 in the COVID-19 Outbreak. Genes 2020, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, K.K.; Mishra, S.; Dixit, A.; Chang, C.-Y. Public Opinions about Online Learning during COVID-19: A Sentiment Analysis Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, F.; Pizzol, D.; Marotta, C.; Antunes, M.; Racalbuto, V.; Veronese, N.; Smith, L. Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) Current Status and Future Perspectives: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Warner, M.E. COVID-19 Policy Differences across US States: Shutdowns, Reopening, and Mask Mandates. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; McFadden, B.R. Consumer food buying during a recession. Choices 2021, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, K.L.; Yenerall, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, T.E. US consumers’ online shopping behaviors and intentions during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2021, 53, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, S.H.; Yaroch, A.L.; Blanck, H.M. Reported Changes in Eating Habits Related to Less Healthy Foods and Beverages during the COVID-19 Pandemic among US Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, P.K.; Lawler, S.; Durham, J.; Cullerton, K. The food choices of US university students during COVID-19. Appetite 2021, 161, 105130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whatnall, M.C.; Patterson, A.J.; Hutchesson, M.J. Effectiveness of Nutrition Interventions in Vending Machines to Encourage the Purchase and Consumption of Healthier Food and Drinks in the University Setting: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cradock, A.L.; Barrett, J.L.; Daly, J.G.; Mozaffarian, R.S.; Stoddard, J.; Her, M.; Etingoff, K.; Lee, R.M. Evaluation of efforts to reduce sodium and ensure access to healthier beverages in four healthcare settings in Massachusetts, US 2016–2018. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 27, 101788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, S.V.; Ickovics, J.R. Vending machines: A narrative review of factors influencing items purchased. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1578–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubik, M.Y.; Wall, M.; Shen, L.; Nanney, M.S.; Nelson, T.F.; Laska, M.N.; Story, M. State but not district nutrition policies are associated with less junk food in vending machines and school stores in US public schools. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Johnson, M.; Quick, V.M.; Walsh, J.; Greene, G.W.; Hoerr, S.; Hoerr, S.; Colby, S.M.; Kattelmann, K.K.; Phillips, B.W.; et al. Sweet and salty. An assessment of the snacks and beverages sold in vending machines on US post-secondary institution campuses. Appetite 2012, 58, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onufrak, S.J.; Zaganjor, H.; Moore, L.V.; Hamner, H.C.; Kimmons, J.E.; Maynard, L.M.; Harris, D. Foods consumed by US adults from cafeterias and vending machines: NHANES 2005 to 2014. Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharis, M.L.; Colby, L.; Wagner, A.; Mallya, G. Sales of healthy snacks and beverages following the implementation of healthy vending standards in City of Philadelphia vending machines. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebe, B.O.; Van Der Lee, J.; Kilelu, C.W. Milk vending machine retail innovation in kenyan urban markets: Operational costs, consumer perceptions and milk quality. HSOA J. Dairy Res. Technol. 2021, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataike, J.; Kulaba, J.; Mugenyi, A.R.; De Steur, H.; Gellynck, X. Would you purchase milk from a milk ATM? Consumers’ attitude as a key determinant of preference and purchase intention in uganda. Agrekon 2019, 58, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labohm, K.; Baaken, D.; Hess, S. Micro market structures of milk vending machines in Germany. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Economic and Social Sciences of Agriculture Association, Transformation Processes in Agriculture and Food Systems. Challenges for Economics and Social Sciences. Berlin, Germany, 22–24 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jairoun, A.A.; Abdulla, N.M.; Shahwan, M.; Bilal, F.H.J.; Al-Tamimi, S.K.; Jairoun, M.; Zyoud, S.H.; Kurdi, A.; Godman, B. Acceptability and willingness of UAE residents to use OTC vending machines to deliver self-testing kits for Covid-19 and the implications. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 1759–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heins, C. The impact of COVID-19 on the grocery retail industry: Innovative approaches for contactless store concepts in Germany. Foresight 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBISWorld. Vending Machine Operators Industry in the US—Market Research Report. Available online: https://www.ibisworld.com/united-states/market-research-reports/vending-machine-operators-industry/ (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Chenarides, L.; Grebitus, C.; Lusk, J.L.; Printezis, I. Food consumption behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Agribusiness 2021, 37, 44–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roll, S.; Chun, Y.; Kondratjeva, O.; Despard, M.; Schwartz-Tayri, T.M.; Grinstein-Weiss, M. Household Spending Patterns and Hardships during COVID-19: A Comparative Study of the US and Israel. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2022, 43, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etumnu, C.E.; Widmar, N.O. Grocery shopping in the digital era. Choices 2020, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Vyt, D.; Jara, M.; Mevel, O.; Morvan, T.; Morvan, N. The impact of convenience in a click and collect retail setting: A consumer-based approach. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 248, 108491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, B.; Ocepek, M.; Kalaitzandonakes, M. US household food acquisition behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e271522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Shopping for Food during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Information for Consumers. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-during-emergencies/shopping-food-during-covid-19-pandemic-information-consumers (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Kassas, B.; Nayga, R.M., Jr. Understanding the importance and timing of panic buying among US Households during the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Kim, J.W.; Jia, W. Health pandemic in the era of (mis) information: Examining the utility of using victim narrative and social endorsement of user-generated content to reduce panic buying in the US. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.; Maske, A.; Rajankar, O. Smart Snacks Vending Machine using Cashless Payment. Int. J. Opt. Sci. 2020, 6, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, M.; Dean, D.L.; Baird, T.; Kambuta, J. Should I Pay or Should I Grow? Factors Which Influenced the Preferences of US Consumers for Fruit, Vegetables, Wine and Beer during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Foods 2022, 11, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meike, R.; Dean, D.L.; Baird, T. Understanding Apple Attribute Preferences of US Consumers. Foods 2022, 11, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, R.; Infante, R.; Kusch, C.; Contador, L.; Pacheco, I.; Mesa, K. Do consumers evaluate new and existing fruit varieties in the same way? Modeling the role of search and experience intrinsic attributes. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2020, 26, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, M.C.; Rouphael, Y. Towards a new definition of quality for fresh fruits and vegetables. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 234, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantin, C.M.; Gracia, A. Intrinsic and extrinsic attributes related to the influence of growing altitude on consumer acceptability and sensory perception of fresh apple. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, S. A step-by-step procedure to implement discrete choice experiments in Qualtrics. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2022, 39, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.K.; Paolacci, G. Crowdsourcing consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, E. The mechanical Turk: A short history of ‘artificial artificial intelligence’. Cult. Stud. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCredie, M.N.; Morey, L.C. Who are the Turkers? A characterization of MTurk workers using the personality assessment inventory. Assessment 2019, 26, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litman, L.; Robinson, J. Conducting Online Research on Amazon Mechanical Turk and Beyond; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, C.; Jian, J.; Pitts, M. Frustration and ennui among Amazon MTurk workers. Behav. Res. Methods 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greszki, R.; Meyer, M.; Schoen, H. Exploring the effects of removing “too fast” responses and respondents from web surveys. Public Opin. Q. 2015, 79, 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.E.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, D.S.; Milenkovic, A.M.; Djordjevic, A.I. Improving the Concept of Medication Vending Machine in the Light of COVID-19 and other Pandemics. In Proceedings of the 55th International Scientific Conference on Information, Communication and Energy Systems and Technologies (ICEST), Nis, Serbia, 10–12 September 2020; pp. 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M.; Plichta, M.; Królak, M. Consumers’ fears regarding food availability and purchasing behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: The importance of trust and perceived stress. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, N.; van der Cruijsen, C.; Bijlsma, M.; Bolt, W. Pandemic payment patterns. J. Bank. Financ. 2022, 143, 106593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Papadaki, A. Nutritional value of foods sold in vending machines in a UK University: Formative, cross-sectional research to inform an environmental intervention. Appetite 2016, 96, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asioli, D.; Varela, P.; Hersleth, M.; Almli, V.L.; Olsen, N.V.; Naes, T. A discussion of recent methodologies for combining sensory and extrinsic product properties in consumer studies. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasek, B.; Lakner, Z.; Temesi, Á. I Believe It Is Healthy—Impact of Extrinsic Product Attributes in Demonstrating Healthiness of Functional Food Products. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongprawmas, R.; Canavari, M. Consumers’ willingness-to-pay for food safety labels in an emerging market: The case of fresh produce in Thailand. Food Policy 2017, 69, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavari, M.; Bazzani, G.M.; Spadoni, R.; Regazzi, D. Food safety and organic fruit demand in Italy: A survey. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, S.B.J.; Wu, Q.; McGuirt, J.T.; Crawford, T.W.; Keyserling, T.C.; Ammerman, A.S. Associations between access to farmers’ markets and supermarkets, shopping patterns, fruit and vegetable consumption and health indicators among women of reproductive age in eastern North Carolina, USA. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1944–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewawitharana, S.C.; Webb, K.L.; Strochlic, R.; Gosliner, W. Comparison of Fruit and Vegetable Prices between Farmers’ Markets and Supermarkets: Implications for Fruit and Vegetable Incentive Programs for Food Assistance Program Participants. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Freq. | % | US Census | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | 55 | 14.1 | 12 |

| 25–34 | 111 | 28.4 | 18 |

| 35–44 | 83 | 21.2 | 16 |

| 45–54 | 80 | 20.5 | 16 |

| 55–64 | 42 | 10.7 | 17 |

| 65+ | 20 | 5.1 | 21 |

| Total | 391 | 100 | 100 |

| Education | |||

| Did not finish high school | 8 | 2.0 | 11 |

| Finished high school | 57 | 14.6 | 27 |

| Attended University | 37 | 9.5 | 20 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 222 | 56.8 | 29 |

| Postgraduate Degree | 67 | 17.1 | 13 |

| Total | 391 | 100 | 100 |

| Household Annual Income | |||

| $0 to $24,999 | 42 | 10.7 | 18 |

| $25,000 to $49,999 | 133 | 34.0 | 20 |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 123 | 31.5 | 18 |

| $75,000 to $99.999 | 68 | 17.4 | 13 |

| $100,000 or higher | 25 | 6.4 | 31 |

| Total | 391 | 100 | 100 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 194 | 49.6 | 49 |

| Female | 197 | 50.4 | 51 |

| Total | 391 | 100 | 100 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 69 | 17.9 | 17 |

| South | 213 | 55.2 | 38 |

| Midwest | 67 | 17.4 | 21 |

| West | 37 | 9.6 | 24 |

| Total | 386 | 100 | 100 |

| Scales and Items | Mean | Std. Dev. | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 FVM Benefits | 5.18 | 1.20 | 0.863 | 0.901 | 0.645 | |

| A fruit vending machine is beneficial in COVIDian times because there is no human interaction | 5.11 | 1.55 | 0.793 | |||

| A fruit vending machine is beneficial in COVIDian times because the pay is contactless | 5.30 | 1.42 | 0.789 | |||

| A fruit vending machine is beneficial in COVIDian times because I can still visually inspect the product | 5.19 | 1.51 | 0.837 | |||

| A fruit vending machine is beneficial in COVIDian times because I do not have to rely on delivery | 5.19 | 1.50 | 0.783 | |||

| A fruit vending machine is beneficial in COVIDian times because I am not exposed to panic buying | 5.07 | 1.51 | 0.813 | |||

| FVM Convenience Benefits | 5.41 | 1.08 | 0.767 | 0.865 | 0.682 | |

| I would save time if I purchased fruit from a vending machine | 5.23 | 1.44 | 0.796 | |||

| I think buying fruit from a vending machine would be convenient | 5.47 | 1.28 | 0.866 | |||

| It would be easy to buy fruit from a vending machine | 5.52 | 1.21 | 0.814 | |||

| FVM Experience Benefits | 4.94 | 1.44 | 0.864 | 0.917 | 0.787 | |

| I think buying fruit from a vending machine would be fun | 5.17 | 1.50 | 0.878 | |||

| I think buying fruit from a vending machine would be exciting | 4.88 | 1.66 | 0.903 | |||

| It would be a sensory stimulating experience to buy fruit from a vending machine | 4.74 | 1.73 | 0.880 | |||

| FVM Quality/Value benefits | 4.99 | 1.36 | 0.869 | 0.920 | 0.793 | |

| I think fruit sold in a vending machine would be of good quality | 5.10 | 1.49 | 0.873 | |||

| Fruit sold at a vending machine would be affordable | 5.00 | 1.55 | 0.900 | |||

| Fruit sold at a vending machine would be good value for money | 4.85 | 1.55 | 0.898 | |||

| FVM Safe and Fresh Benefits | 5.21 | 1.19 | 0.827 | 0.897 | 0.743 | |

| I think buying fruit from a vending machine would be safe | 5.20 | 1.29 | 0.868 | |||

| I think that the fruit offered in a vending machine would be fresh | 5.03 | 1.54 | 0.861 | |||

| It would be useful to have fruit available in vending machines | 5.36 | 1.34 | 0.858 | |||

| Impact of COVID-19 | 5.10 | 1.30 | 0.864 | 0.902 | 0.649 | |

| Since COVID-19, I actively avoid contact with other people in the supermarket | 5.01 | 1.61 | 0.862 | |||

| Since COVID-19, my preference for online shopping has increased | 5.23 | 1.53 | 0.766 | |||

| Since COVID-19, my preference for contactless payment has increased | 5.26 | 1.58 | 0.814 | |||

| Since COVID-19, I wear a mask and gloves for food shopping | 4.98 | 1.78 | 0.810 | |||

| Since COVID-19, I disinfect more | 5.00 | 1.59 | 0.772 | |||

| Importance of Intrinsic Attributes | 5.41 | 0.97 | 0.767 | 0.851 | 0.588 | |

| Importance that the color of the fruit skin is intense | 5.12 | 1.30 | 0.789 | |||

| Importance that fruit smell is appealing | 5.51 | 1.17 | 0.780 | |||

| Importance that fruit texture is attractive | 5.53 | 1.26 | 0.803 | |||

| Importance that fruit skin is free of optical blemishes | 5.53 | 1.32 | 0.691 | |||

| Important of Extrinsic Attributes | 5.22 | 1.18 | 0.850 | 0.893 | 0.626 | |

| Importance that fruit labeled as sustainable | 5.10 | 1.51 | 0.862 | |||

| Importance that fruit is labeled as organic | 5.01 | 1.64 | 0.801 | |||

| Importance that fruit is packaged conveniently | 5.29 | 1.43 | 0.828 | |||

| Importance that fruit packaging is minimal | 5.20 | 1.42 | 0.728 | |||

| Importance that fruit has a long shelf life | 5.47 | 1.41 | 0.728 | |||

| Willingness to Consume from a FVM (Individual items) | ||||||

| I am willing to try fruit from a vending machine | 5.37 | 1.38 | ||||

| I am willing to buy fruit from a vending machine. | 5.35 | 1.40 | ||||

| I am willing to pay a price premium for fruit from a vending machine | 4.70 | 1.84 |

| Fornell-Larcker Criterion | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A COVID-19 FVM Benefits | 0.803 | |||||||

| B FVM Convenience Benefits | 0.593 | 0.826 | ||||||

| C FVM Experience Benefits | 0.604 | 0.608 | 0.887 | |||||

| D FVM Quality/Value benefits | 0.646 | 0.620 | 0.746 | 0.890 | ||||

| E FVM Safe and Fresh Benefits | 0.659 | 0.631 | 0.671 | 0.750 | 0.862 | |||

| F Impact of COVID-19 | 0.683 | 0.411 | 0.442 | 0.464 | 0.465 | 0.805 | ||

| G Importance of Intrinsic Attributes | 0.494 | 0.486 | 0.442 | 0.425 | 0.419 | 0.526 | 0.767 | |

| H Important of Extrinsic Attributes | 0.592 | 0.404 | 0.512 | 0.534 | 0.458 | 0.571 | 0.654 | 0.791 |

| Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H |

| B FVM Convenience Benefits | 0.725 | |||||||

| C FVM Experience Benefits | 0.695 | 0.739 | ||||||

| D FVM Quality/Value benefits | 0.742 | 0.753 | 0.860 | |||||

| E FVM Safe and Fresh Benefits | 0.776 | 0.786 | 0.792 | 0.884 | ||||

| F Impact of COVID-19 | 0.792 | 0.506 | 0.511 | 0.534 | 0.549 | |||

| G Importance of Intrinsic Attributes | 0.601 | 0.632 | 0.537 | 0.515 | 0.517 | 0.639 | ||

| H Important of Extrinsic Attributes | 0.688 | 0.494 | 0.593 | 0.619 | 0.548 | 0.667 | 0.803 |

| Hypothesized Relationship | Coefficient | T Stat. | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Impact of COVID-19 → Pandemic benefits | 0.683 | 15.43 | 0.000 |

| H2a: Pandemic-related FVM benefits → willingness to try | 0.156 | 1.84 | 0.066 |

| H2b: Pandemic-related FVM benefits → willingness to buy | 0.134 | 1.57 | 0.116 |

| H2c: Pandemic-related FVM benefits → willingness to pay more | 0.188 | 2.71 | 0.007 |

| H3: Intrinsic fruit attributes → FVM safety/freshness benefits | 0.419 | 6.16 | 0.000 |

| H4: Intrinsic fruit attributes → FVM quality/value benefits | 0.133 | 1.96 | 0.050 |

| H5: Extrinsic fruit attributes → FVM quality/value benefits | 0.447 | 6.14 | 0.000 |

| H6: Extrinsic fruit attributes → FVM convenience benefits | 0.404 | 6.24 | 0.000 |

| H7: Extrinsic fruit attributes → FVM experience benefits | 0.512 | 9.31 | 0.000 |

| H8a: FVM safety/freshness-related benefits → willingness to try | 0.270 | 2.61 | 0.009 |

| H8b: FVM safety/freshness-related benefits → willingness to buy | 0.431 | 4.80 | 0.000 |

| H8c: FVM safety/freshness-related benefits → willingness to pay more | −0.064 | 0.79 | 0.429 |

| H9a: FVM quality/value-related benefits → willingness to try | 0.075 | 0.79 | 0.432 |

| H9b: FVM quality/value-related benefits → willingness to buy | −0.007 | 0.09 | 0.929 |

| H9c: FVM quality/value-related benefits → willingness to pay more | 0.483 | 5.35 | 0.000 |

| H10a: FVM convenience-related benefits → willingness to try | 0.251 | 3.41 | 0.001 |

| H10b: FVM convenience-related benefits → willingness to buy | 0.197 | 2.85 | 0.004 |

| H10c: FVM convenience-related benefits → willingness to pay more | −0.184 | 2.88 | 0.004 |

| H11a: FVM experience-related benefits → willingness to try | 0.050 | 0.60 | 0.551 |

| H11b: FVM experience-related benefits → willingness to buy | 0.089 | 1.17 | 0.241 |

| H11c: FVM experience-related benefits → willingness to pay more | 0.365 | 4.74 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rombach, M.; Dean, D.L.; Baird, T.; Rice, J. Fruit Vending Machines as a Means of Contactless Purchase: Exploring Factors Determining US Consumers’ Willingness to Try, Buy and Pay a Price Premium for Fruit from a Vending Machine during the Coronavirus Pandemic. COVID 2022, 2, 1650-1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid2120119

Rombach M, Dean DL, Baird T, Rice J. Fruit Vending Machines as a Means of Contactless Purchase: Exploring Factors Determining US Consumers’ Willingness to Try, Buy and Pay a Price Premium for Fruit from a Vending Machine during the Coronavirus Pandemic. COVID. 2022; 2(12):1650-1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid2120119

Chicago/Turabian StyleRombach, Meike, David L. Dean, Tim Baird, and Jill Rice. 2022. "Fruit Vending Machines as a Means of Contactless Purchase: Exploring Factors Determining US Consumers’ Willingness to Try, Buy and Pay a Price Premium for Fruit from a Vending Machine during the Coronavirus Pandemic" COVID 2, no. 12: 1650-1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid2120119

APA StyleRombach, M., Dean, D. L., Baird, T., & Rice, J. (2022). Fruit Vending Machines as a Means of Contactless Purchase: Exploring Factors Determining US Consumers’ Willingness to Try, Buy and Pay a Price Premium for Fruit from a Vending Machine during the Coronavirus Pandemic. COVID, 2(12), 1650-1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid2120119