“Being There for Each Other”: Hospital Nurses’ Struggle during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Recruitment

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection and Abstraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

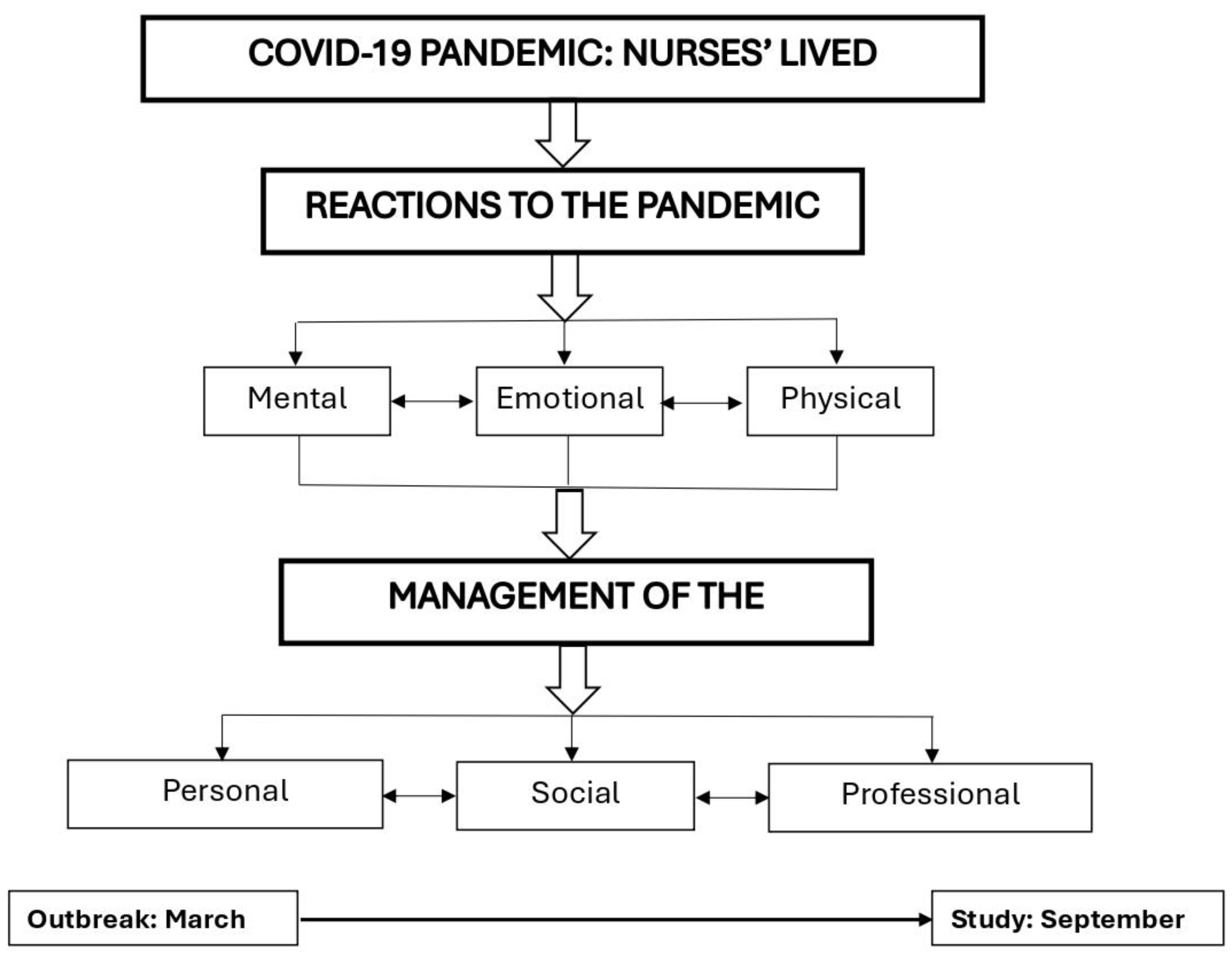

3.1. Nurses’ Reactions to the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.1.1. Mental Reactions

“When I witnessed the extreme deterioration of patients from the moment of admission when they could talk to me until they passed away a few hours later, I said to myself, this is a serious and unexpected disease that can really cause troubles.” P5

“At first, we didn’t understand exactly what was going on. When I had to transfer lab specimens from the respiratory ER, I would move the divider and hand it over to another staff member who would send it to the lab. Only later did we realize that this was not right, and we constructed walls and double doors where the specimens could be put safely.” P16

“The inability to provide answers to the good questions of patients and families because of our lack of knowledge was difficult. At that point in time, instructions were confusing and changed from moment to moment. When you are faced with such reality at work, then all your clinical senses are undermined.” P14

“We at the bedside were very confused, we were shifted from place to place [...] There were situations I would arrive in the morning, and I wouldn’t know to which department I would be allocated. There was a long period of uncertainty and organizational disorder. The whole period lasted almost a year on and off.” P20

“From the beginning, it was clear to me that I would volunteer someday to take care of COVID-19 patients. [...] it intrigued me to understand what this pandemic is. In the medical department, we treat a lot of patients with respiratory problems. Everyone who worked in the COVID-19 department kept telling us that it was something different. [...] When I got there, I realized how different it was.” P19

“I dealt with it because it felt like a war; you must continue taking care of people. You see people dying in front of your eyes. It’s hard, we went through very difficult days, but we dealt with it. We must help and try to save lives.” P18

3.1.2. Emotional Reactions

“It was very scary; I was afraid to return home. I feared I would be the cause of infecting my mom and my kids, causing them a serious illness or God forbid death. It was the toughest experience.” P15

“I felt anxiety and fear because of the continuous changes and the uncertainty in the air. Each time, new instructions and everyone says something different. You feel helpless in this situation. There was no certainty and no other choice.... people do not understand what the term “exhaustion” means; what is extreme tiredness when a person wears PPE for seven hours during a shift; what it means to go through one resuscitation after another, while in front of me, several patients are collapsing at the same time and I do not know to whom to turn to first; to whom I will be sufficient to care for and to whom I will not. It tears your soul apart.” P22

“We were kind of heroes on the frontline; I was not afraid to run forward, it was not a problem.” P16

“In terms of personal feelings, there was a feeling that I am part of something big that is happening, and my contribution here counts.” P18

3.1.3. Physical Reactions

“I arrived very tired at the hospital shifts; I did not sleep well at night. [...] I had strong dizziness; there were times I felt I could not stand it anymore.” P12

“There were very tough days I would collapse with headaches. We did not rest for a moment, there was work all the time and I already had blisters on my feet. I am also a shift charge nurse and so I would have to stay longer shifts and it was tiring and exhausting.” P7

“We put on protective equipment from head to toe. The N95 masks were tight in a way that hurt us. I remember I had a wound behind my ear and on my face. I was afraid to drink before a shift because there was no option to go to the toilet. You are sweating and wet on the inside and all you want to do is go out for a moment and breathe oxygen.” P10

“The hardest thing is the full protection; the unit is crowded, small, and hot. The difficulty breathing and at the same time getting into resuscitation is difficult. I didn’t see what I was doing. In addition, the PPE creates a physical barrier between you and the patient; it does not help the situation.” P14

3.2. Management of the Traumatic Event

3.2.1. Personal Resources

“I gained a lot of experiences in my professional life and there were a lot of tough situations [...]. I never shouted or cried in the middle of a shift, but during the pandemic, it did happen to me underneath the mask.” P20

“Most of the time we treat patients who are in very difficult conditions with poor prognosis. Sometimes I feel like I’m becoming an emotionless person and the dead are becoming numbers. Entered-died, entered–died [...] It’s a terrible feeling but that’s what helps [...] I started giving time to myself, reading, and writing about things that upset me. I’d come back from a shift exhausted and I’d get home and write down all the bad stuff and release it. I would leave a shift sometimes crying and a lot of emotions would float, this gave me the option to let go of everything and be alone with myself for a few moments.” P12

“I can’t go on vacation and travel as much as I want. I must take care of my dad and kids. Everything adds worries but life continues, we got vaccinated and if we follow the instructions, then nothing will prevent us from meeting friends and going to the movies soon.” P19

“I go to a cafe at 07:00 o’clock in the morning after my night shift when there is no one outside and it’s quiet, the birds are tweeting, order a cup of coffee and a snack, and experience at least 20 min of quiet, without the noise and the nonstop buzzing of the devices and monitors, without the patients’ shouts, and without the noise of the staff. Sitting in a cafe in the morning, the silence refreshes and restarts me every time. When I come home, then what relaxes me is the cleaning and scrubbing of the house. It gives me a break and relaxation. Unfortunately, my obsession with cleanliness got worse during the COVID period, but this is how I am now. Until I rub away all the frustrations I don’t relax, only after everything is clean and organized can I go to sleep in peace.” P10

3.2.2. Social Support

“I mostly remember an experience of support and pride. My partner was proud of me and showed it off in front of everyone. [...] My mother was very anxious. She is 83 years old; she took it more to a place of concern. The children and my partner mainly demonstrated support and pride. The children took care of all household chores because I was not available.” P8

“I had not seen my mother for a long time, which was very difficult. On her birthday I arrived at the building where she lives and could only see her from a distance without touching her. My comrades from the military service showed interest in my work at the hospital, they asked me to send them pictures of me with the full protective equipment and they couldn’t believe it. I am a person who loves to share, so the relationship with friends made me feel good.” P17

“All kinds of indulgences and sweets made the personnel smile. Ordinary people would donate cakes and cheese, children would create videos, and it felt good to know that they did it with appreciation and wholeheartedly.” P15

“In the first wave, because we were at the forefront of the pandemic, we received a lot of gifts and food that people donated. Both patients and companies donated to the hospital staff [...]. We felt that we had strong support from people, society, and the workplace.” P18

3.2.3. Professional Support

“We are in a kind of chaos and there are changes all the time. I have been in the healthcare system for 20 years, and it seems now like a survival battle. I felt that they [managers] were scared, disorganized, and did not know what to do and how to survive. By and large, they tried to supply food because we worked 12-h shifts and could not go out to buy.” P20

“The social worker approached me after observing that I was very nervous. We talked for about an hour, and it was a good release and stress relief conversation. It helped and I would occasionally go to her, but I didn’t have much time for attending the meetings.” P17

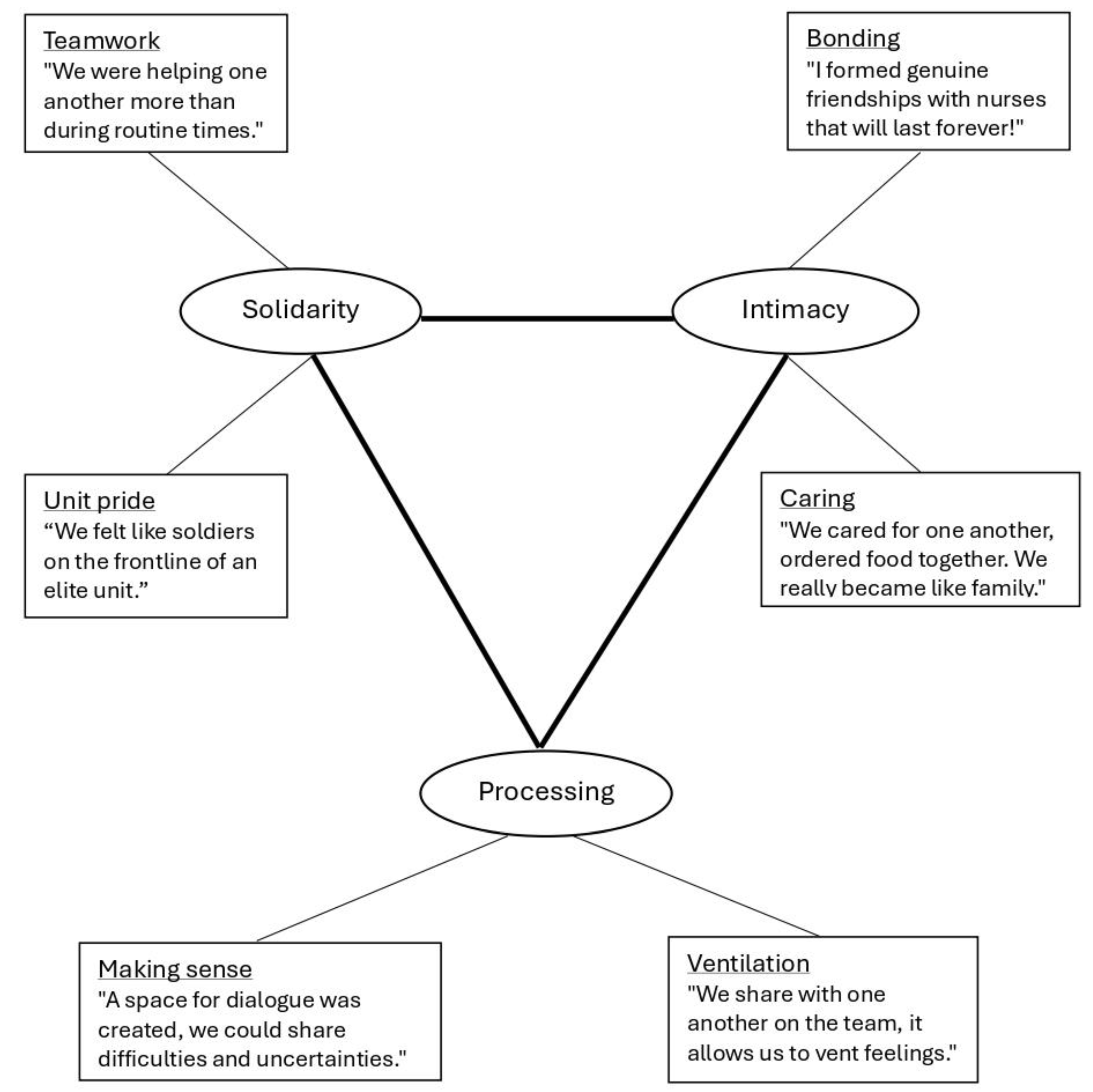

“Something in the experience of fear and not knowing where it was going, that accompanied the staff and the patients, united us. We wanted to defeat the fear by being there for each other. There was a feeling of solidarity and that we were in a strong position and could give something that no one else could. It was a capsule not only in the literal physical sense but also in the emotional sense of unity. A capsule in the sense that it was closed, special, different, distinct, separate, and only we could do it [...] each capsule was a unit camaraderie; there was something intimate about it in the best sense of the word. I haven’t experienced anything like this in the whole time I’ve been on duty as a nurse.” P8

“When I joined the COVID-19 department, I didn’t feel alone. I felt I had a listening ear. Even if we did not talk, we would sometimes sit together in silence. When you develop a very high level of intimacy with a person, then you get comfortable. We were a team of diverse backgrounds: Jews, Muslims, Christians-all kinds; an intimacy of understanding was created between us only from a glance.” P20

“What has helped me the most is the staff themselves; we sometimes talked outside of work, after the shift, and between shifts, and a lot of them have become my friends and that helps me a lot.” P12

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Work

4.2. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Relevance to Education, Practice, and Policy

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boone, L.D.; Rodgers, M.M.; Baur, A.; Vitek, E.; Epstein, C. An integrative review of factors and interventions affecting the well-being and safety of nurses during a global pandemic. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2023, 20, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D. Reflections on nursing research focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, e84–e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, E.; Widestrom, M.; Gould, J.; Fang, R.; Davis, K.G.; Gillespie, G.L. Examining the impact of stressors during COVID-19 on emergency department healthcare workers: An international perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, E.T.; Narva, A.M.; Holland, S.; Smith, J.G.; Cramer, E.; Rosenbaum, K.E.F.; French, R.; Clark, R.R.S.; Rogowski, J.A. Hospital nurses’ moral distress and mental health during COVID-19. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, C.T.; Trask, C.M.; Rafiq, M.; MacKay, L.J.; Letourneau, N.; Ng, C.F.; Keown-Gerrard, J.; Gilbert, T.; Ross, K.M. Experiences and Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Thematic Analysis. COVID 2024, 4, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, İ.; Taylan, S. Experiences of nurses providing care for patients with COVID-19 in acute care settings in the early stages of the pandemic: A thematic meta-synthesis study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2023, 29, e13143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, Y.; Güdül Öz, H.; Akgün, M.; Boz, İ.; Yangın, H. Qualitative exploration of nurses’ experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic using the reconceptualized uncertainty in illness theory: An interpretive descriptive study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greinacher, A.; Derezza-Greeven, C.; Herzog, W.; Nikendei, C. Secondary traumatization in first responders: A systematic review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1562840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, G.; Feng, R.; Wang, W.; Xu, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L. Anxiety, depression and insomnia: A cross-sectional study of frontline staff fighting against COVID-19 in Wenzhou, China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkuş, Y.; Karacan, Y.; Güney, R.; Kurt, B. Experiences of nurses working with COVID-19 patients: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 31, 1243–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vivar, C.; Rodríguez-Matesanz, I.; San Martín-Rodríguez, L.; Soto-Ruiz, N.; Ferraz-Torres, M.; Escalada-Hernández, P. Analysis of mental health effects among nurses working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs 2022, 30, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EI Hussein, M.T.; Mushaluk, C. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Nursing Students and New Graduate Nurses: A Scoping Review. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2024, 38, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, C.Y.; Lee, B. Systematic Review of Mind–Body Modalities to Manage the Mental Health of Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Era. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.D.; Urban, R.W.; Foglia, D.C.; Henson, J.S.; George, V.; McCaslin, T. Well-being in acute care nurse managers: A risk analysis of physical and mental health factors. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2023, 20, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohisha, I.K.; Jibin, M. Stressors and coping strategies among frontline nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2023, 12, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmari, M.; Nayeri, N.D.; Palese, A.; Manookian, A. Nurses’ safety-related organizational challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2023, 70, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magliano, L.; Papa, C.; Di Maio, G.; Bonavigo, T. Staff opinions on the most positive and negative changes in mental health services during the 2 years of the pandemic emergency in Italy. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health 2024, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Wei, L.; Shi, S.; Jiao, D.; Song, R.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; You, Y.; et al. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2020. 48, 592–598. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, Y.; Baghaei, R.; Hosseingholipour, K.; Mollazadeh, F. Challenges experienced by ICU nurses throughout the provision of care for COVID-19 patients: A qualitative study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, C.; James, S.; Williams, A.; Calma, K.; Mcinnes, S.; Mursa, R.; Stephen, C.; Halcomb, E. The psychological well-being of primary healthcare nurses during COVID-19: A qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3820–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahapatro, M.; Prasad, M.M. The experiences of nurses during the COVID-19 crisis in India and the role of the state: A qualitative analysis. Public Health Nurs. 2023, 40, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maben, J.; Bridges, J. Covid-19: Supporting nurses’ psychological and mental health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2742–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Murphy, D.; Regel, S. An affective–cognitive processing model of post-traumatic growth. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 19, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foli, K.J.; Forster, A.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, L.; Chiu, Y.C. Voices from the COVID-19 frontline: Nurses’ trauma and coping. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3853–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konwar, G.; Kakati, S.; Sarma, N. Experiences of nursing professionals involved in the care of COVID-19 patients: A qualitative study. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 2022, 6, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M.; Pien, L.C.; Kao, C.C.; Kubo, T.; Cheng, W.J. Effects of work conditions and organizational strategies on nurses’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbuAlRub, R.F. Job stress, job performance, and social support among hospital nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2004, 36, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Gender | Age (Years) | Family Status | Native Language | Prof. Educ. | Nursing Experience (Years) | COVID-19 Experience (Month) | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 28 | S | Hebrew | MA | 1 | 2 | SN |

| 2 | F | 33 | M | Russian | MA | 5 | 24 | SN |

| 3 | M | 34 | M+1 | Arabic | MA | 10 | 18 | SN |

| 4 | F | 27 | M | Russian | MA | 1 | 2 | SN |

| 5 | F | 47 | M+2 | Russian | MA | 25 | 24 | SN |

| 6 | F | 42 | M+4 | Russian | MA | 10 | 24 | NM |

| 7 | F | 33 | M+2 | Arabic | BA | 12 | 24 | SN |

| 8 | F | 54 | M+3 | Russian | MA | 32 | 24 | NM |

| 9 | F | 48 | M+2 | Russian | MA | 17 | 24 | SN |

| 10 | F | 38 | M+1 | Russian | BA | 13 | 18 | SN |

| 11 | M | 29 | M+1 | Arabic | MA | 5 | 24 | SN |

| 12 | F | 28 | M | Arabic | BA | 2 | 12 | SN |

| 13 | F | 48 | M+5 | Hebrew | MA | 5 | 12 | SN |

| 14 | M | 34 | M | Hebrew | BA | 5 | 12 | SN |

| 15 | F | 41 | M+3 | Arabic | MA | 14 | 18 | SN |

| 16 | F | 30 | M+1 | Hebrew | MA | 2 | 18 | SN |

| 17 | M | 46 | M+3 | Hebrew | BA | 21 | 24 | NM |

| 18 | F | 24 | S | Hebrew | BA | 1 | 3 | SN |

| 19 | F | 26 | M+3 | Hebrew | BA | 3 | 3 | SN |

| 20 | F | 46 | M+1 | Russian | PhD | 3 | 18 | SN |

| 21 | F | 42 | S +3 | Russian | BA | 18 | 22 | NM |

| 22 | F | 33 | M+3 | Hebrew | BA | 6 | 6 | SN |

| 23 | M | 29 | S | Arabic | BA | 5 | 6 | SN |

| Category 1: Nurses’ Reactions to the COVID-19 Pandemic | |

|---|---|

| Sub-Category | Themes |

| 1.1. Mental Reactions | 1. Perception of threat, risk, and uncertainty |

| 2. Reframing the meaning of the mission | |

| 1.2. Emotional Reactions | 1. Fear, anxiety, and helplessness |

| 2. Courage, heroism, and team camaraderie | |

| 1.3. Physical Reactions | 1. Physical symptoms of distress |

| 2. Disruption of physiological needs | |

| Category 2: Nurses’ Management of the COVID-19 Pandemic | |

| Sub-Category | Themes |

| 2.1. Personal Resources | 1. Regulation of overwhelming emotions |

| 2. Management of work-life imbalance | |

| 2.2. Social Support | 1. Family & friends: Concern, support, and pride |

| 2. Public: Gratitude and appreciation | |

| 2.3. Professional Support | 1. Managers and therapists: Chaos and sporadic support |

| 2. Colleagues: Solidarity, intimacy, processing, and growth | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Admi, H.; Inchi, L.; Bord, S.; Shahrabani, S. “Being There for Each Other”: Hospital Nurses’ Struggle during the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID 2024, 4, 982-997. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4070068

Admi H, Inchi L, Bord S, Shahrabani S. “Being There for Each Other”: Hospital Nurses’ Struggle during the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID. 2024; 4(7):982-997. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4070068

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdmi, Hanna, Liron Inchi, Shiran Bord, and Shosh Shahrabani. 2024. "“Being There for Each Other”: Hospital Nurses’ Struggle during the COVID-19 Pandemic" COVID 4, no. 7: 982-997. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4070068