Exploring the Impact of Personal and Social Media-Based Factors on Judgments of Perceived Skepticism of COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Sociodemographic Factors

1.3. COVID-19 Anxiety and Interference

1.4. Social Media Use

2. Method

2.1. Procedure and Sample

2.2. Instrumentation

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Model

3.2. Main Effects

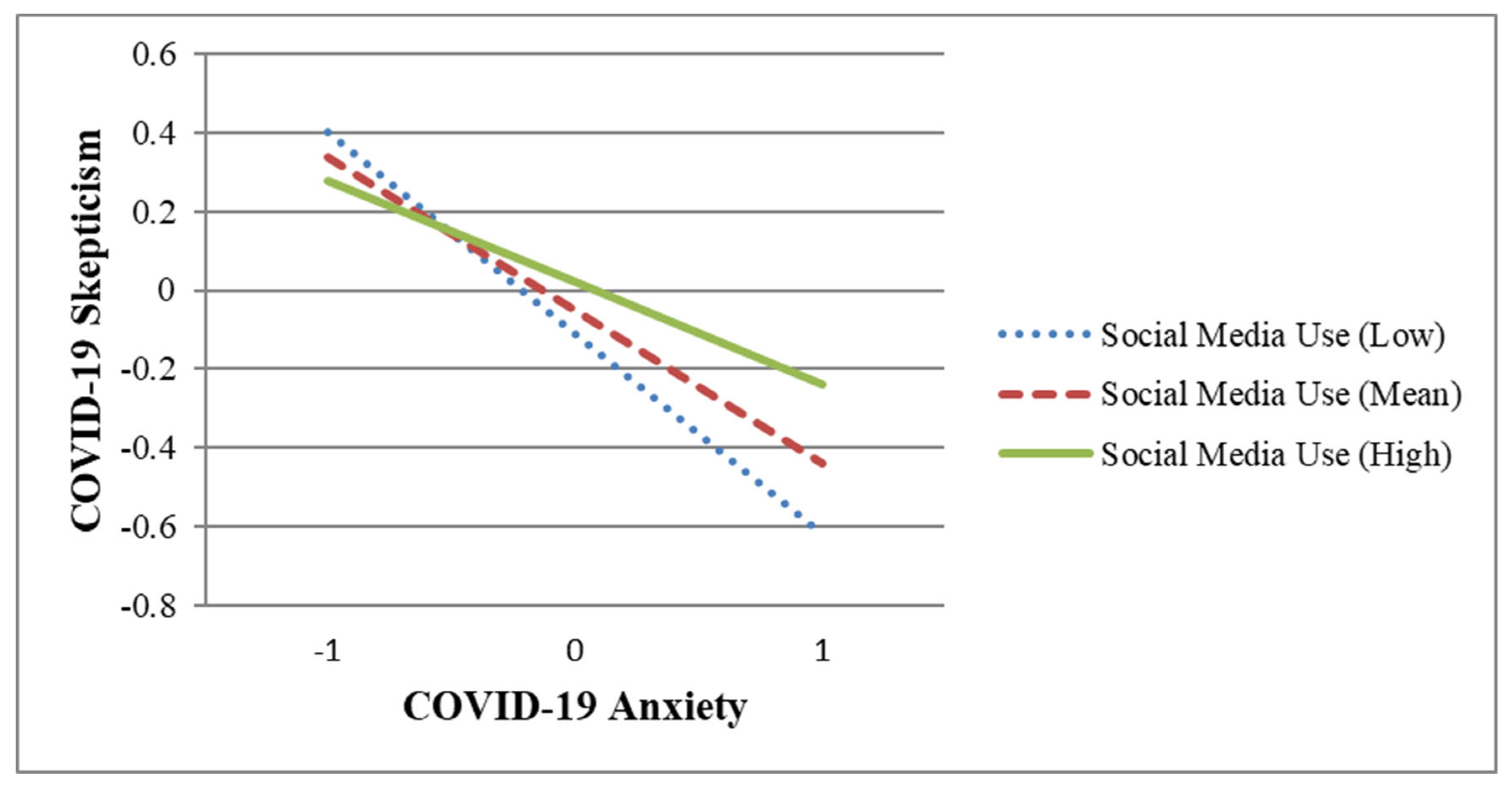

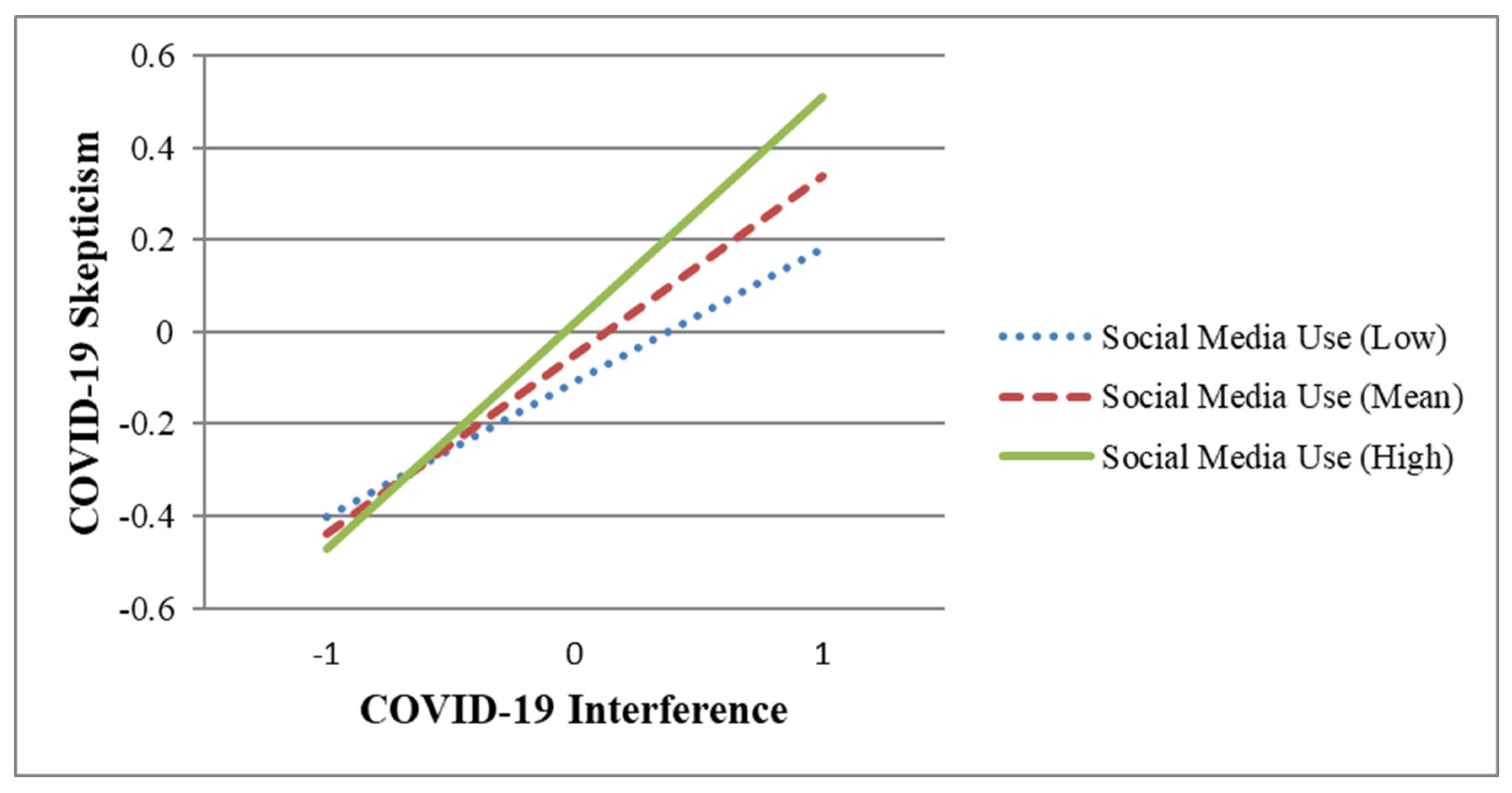

3.3. Non-Additivity

4. Discussion

4.1. Contributions

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Koffman, J.; Gross, J.; Etkind, S.N.; Selman, L. Uncertainty and COVID-19: How are we to respond? J. R. Soc. Med. 2022, 113, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. A Year of U.S. Public Opinion on the Coronavirus Pandemic. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/2021/03/05/a-year-of-u-s-public-opinion-on-the-coronavirus-pandemic/ (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Rajkumar, R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 52, 102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lejano, R.P.; Nero, S.J. The Power of Narrative: Climate Skepticism and the Deconstruction of Science; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Latkin, C.A.; Dayton, L.; Moran, M.; Strickland, J.C.; Collins, K. Behavioral and psychosocial factors associated with COVID-19 skepticism in the United States. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 7918–7926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouzy, R.; Abi Jaoude, J.; Kraitem, A.; El Alam, M.B.; Karam, B.; Adib, E. Coronavirus goes viral: Quantifying the COVID-19 misinformation epidemic on Twitter. Cureus 2020, 12, e7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bierwiaczonek, K.; Kunst, J.R.; Pich, O. Belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories reduces social distancing over time. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2020, 12, 1270–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Eaton, L.A.; Kalichman, S.C.; Brousseau, N.M.; Hill, E.C.; Fox, A.B. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinthe, G.; Brown, G.; Delouvée, S.; Jolley, D. Looking out for myself: Exploring the relationship between conspiracy mentality, perceived personal risk, and COVID-19 prevention measures. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plohl, N.; Musil, B. Modeling compliance with COVID-19 prevention guidelines: The critical role of trust in science. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W. Disease now and potential future pandemics. In The World’s Worst Problems; Spring: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Marani, M.; Katul, G.G.; Pan, W.K.; Parolari, A.J. Intensity and frequency of extreme novel epidemics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2105482118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangleburg, T.F.; Bristol, T. Socialization and adolescents’ skepticism toward advertising. J. Advert. 1998, 27, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklund, E.H.; Scheitle, C.P.; Peifer, J.; Bolger, D. Examining links between religion, evolution views, and climate change skepticism. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 985–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutjens, B.T.; Sutton, R.M.; van der Lee, R. Not all skepticism is equal: Exploring the ideological antecedents of science acceptance and rejection. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 44, 384–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekmat, E. Nudge effect of fact-check alerts: Source influence and media skepticism on sharing of news misinformation in social media. Soc. Media + Soc. 2020, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutjens, B.T.; van der Linden, S.; van der Lee, R. Science skepticism in times of COVID-19. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2021, 24, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrer, J.E.; Borders, T.F. Healthy skepticism. Prev. Med. 2004, 39, 1234–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, Z.J.; Richey, S. Anti-vaccination beliefs and unrelated conspiracy theories. World Aff. 2020, 183, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Gignac, G.E.; Oberauer, K. The role of conspiracist ideation and worldviews in predicting rejection of science. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faasse, K.; Newby, J. Public perceptions of COVID-19 in Australia: Perceived risk, knowledge, health-protective behaviors, and vaccine intentions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 551004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filkuková, P.; Ayton, P.; Rand, K.; Langguth, J. What should I trust? Individual differences in attitudes to conflicting information and misinformation on COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 588478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobkow, A.; Zaleskiewicz, T.; Petrova, D.; Garcia-Retamero, R.; Traczyk, J. Worry, risk perception, and controllability predict intentions toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 582720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjit, Y.S.; Shin, H.; First, J.M.; Houston, J.B. COVID-19 protective model: The role of threat perceptions and informational cues in influencing behavior. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merolla, A.J.; Otmar, C.; Hernandez, C.R. Day-to-day relational life during the COVID-19 pandemic: Linking mental health, daily relational experiences, and end-of-day outlook. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2021, 38, 2350–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latkin, C.; Dayton, L.A.; Yi, G.; Konstantopoulos, A.; Park, J.; Maulsby, C.; Kong, X. COVID-19 vaccine intentions in the United States, a social-ecological framework. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2288–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutjens, B.T.; Sengupta, N.; der Lee, R.; van Koningsbruggen, G.M.; Martens, J.P.; Rabelo, A.; Sutton, R.M. Science Skepticism across 24 Countries. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2022, 13, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S. Impact of pandemic proximity and media use on risk perception during COVID-19 in China. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2022, 13, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H. Media exposure to COVID-19 information, risk perception, social and geographical proximity, and self-rated anxiety in China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alper, S.; Bayrak, F.; Yilmaz, O. Psychological correlates of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and preventive measures: Evidence from Turkey. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 5708–5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Bwire, G.M. Coronavirus: Why men are more vulnerable to COVID-19 than women? SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020, 2, 874–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, T.M.; Eslen-Ziya, H. The differential impact of COVID-19 on the work conditions of women and men academics during the lockdown. Gend. Work Organ. 2021, 28, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo Clinic. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/expert-answers/coronavirus-infection-by-race/faq-20488802 (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; McCaul, K.D.; Weinstein, N.D. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuano, A.; Rossi, F.; Paolisso, G. COVID-19 kills more men than women: An overview of possible reasons. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 561338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dana, P.M.; Sadoughi, F.; Hallajzadeh, J.; Asemi, Z.; Mansournia, M.A.; Yousefi, B.; Momen-Heravi, M. An insight into the sex differences in COVID-19 patients: What are the possible causes? Prehospital Disaster Med. 2020, 35, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zintel, S.; Flock, C.; Arbogast, A.L.; Forster, A.; von Wagner, C.; Sieverding, M. Gender differences in the intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Public Health 2023, 31, 1303–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prichard, E.C.; Christman, S.D. Authoritarianism, conspiracy beliefs, gender and COVID-19: Links between individual differences and concern about COVID-19, mask wearing behaviors, and the tendency to blame China for the virus. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 597671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, R.; Lamberty, P. A bioweapon or a hoax? The link between distinct conspiracy beliefs about the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak and pandemic behavior. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020, 11, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietromonaco, P.R.; Overall, N.C. Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic may impact couples’ relationships. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Reactions to COVID-19: Differential predictors of distress, avoidance, and disregard for social distancing. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.M.; Goh, C.; Lim, L.Z.; Gao, X. COVID-19 Emergency eLearning and Beyond: Experiences and Perspectives of University Educators. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.L.; Smith, D.; Caccavale, L.J.; Bean, M.K. Parents are stressed! Patterns of parent stress across COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 626456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H.; Wu, Q.; Xie, Y.; Deng, J.; Jiang, L.; Gan, X. A Qualitative Investigation of the Psychological Experiences of COVID-19 Patients Receiving Inpatient Care in Isolation. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Ha, J. Changes in daily life during the COVID-19 pandemic among South Korean older adults with chronic diseases: A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lyu, H. Epidemic risk perception, perceived stress, and mental health during COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated mediating model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 563741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commodari, E.; La Rosa, V.L. Adolescents in quarantine during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: Perceived health risk, beliefs, psychological experiences and expectations for the future. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 559951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šrol, J.; Ballová Mikušková, E.; Čavojová, V. When we are worried, what are we thinking? Anxiety, lack of control, and conspiracy beliefs amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2021, 35, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennington, N. Communication outside of the home through social media during COVID-19. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 4, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgman, A.; Merkley, E.; Loewen, P.J.; Owen, T.; Ruths, D.; Teichmann, L.; Zhilin, O. The causes and consequences of COVID-19 misperceptions: Understanding the role of news and social media. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinform. Rev. 2020, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allington, D.; Duffy, B.; Wessely, S.; Dhavan, N.; Rubin, J. Health-protective behaviour, social media usage and conspiracy belief during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 1763–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2020/03/25/americans-who-primarily-get-news-through-social-media-are-least-likely-to-follow-covid-19-coverage-most-likely-to-report-seeing-made-up-news/ (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Yamamoto, M.; Kushin, M.J. More harm than good? Online media use and political disaffection among college students in the 2008 election. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2014, 19, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, S.W.; Sykes, T.A.; Venkatesh, V. Combating COVID-19 fake news on social media through fact checking: Antecedents and consequences. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Xin, M.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Lau, J.T. Behavioural intention of receiving COVID-19 vaccination, social media exposures and peer discussions in China. Epidemiol. Infect. 2021, 149, e158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.M.; High, A.C.; Maragh-Lloyd, R.; Stoldt, R.; Ekdale, B. Trust in online search results during uncertain times. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2022, 66, 751–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, M.; Dyer, S. Information and disinformation: Social media in the COVID-19 crisis. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 27, 640–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obiała, J.; Obiała, K.; Mańczak, M.; Owoc, J.; Olszewski, R. COVID-19 misinformation: Accuracy of articles about coronavirus prevention mostly shared on social media. Health Policy Technol. 2021, 10, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulido, C.M.; Villarejo-Carballido, B.; Redondo-Sama, G.; Gómez, A. COVID-19 infodemic: More retweets for science-based information on coronavirus than for false information. Int. Sociol. 2020, 35, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastin, M.S.; Guinsler, N.M. Worried and wired: Effects of health anxiety on information-seeking and health care utilization behaviors. CyberPsychology Behav. 2006, 9, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freiling, I.; Krause, N.M.; Scheufele, D.A.; Brossard, D. Believing and sharing misinformation, fact-checks, and accurate information on social media: The role of anxiety during COVID-19. New Media Soc. 2023, 25, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Liu, P.L.; Ngien, A.; Wu, Q. The effects of worry, risk perception, information-seeking experience, and trust in misinformation on COVID-19 fact-checking: A survey study in China. Chin. J. Commun. 2022, 16, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S.; Roozenbeek, J.; Compton, J. Inoculating against fake news about COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 566790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarocostas, J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, J.R.; Wright, P.M. Harking, sharking, and tharking: Making the case for post hoc analysis of scientific data. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbing, D.W. Package ‘lessR’. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- R Core Team. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Manata, B.; Boster, F.J. Reconsidering the problem of common-method variance in organizational communication research. Manag. Commun. Q. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.K.; Crimmins, E.M. How does age affect personal and social reactions to COVID-19: Results from the national Understanding America Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillard, J.P.; Shen, L. On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Commun. Monogr. 2005, 72, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WebMD. Coronavirus Recovery. Available online: https://www.webmd.com/covid/covid-recovery-overview (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- High, A.C.; Buehler, E.M. Receiving supportive communication from Facebook friends: A model of social ties and supportive communication in social network sites. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 36, 719–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, M.; McDaniel, B.T.; Pater, J.; Toscos, T. How parents and their children used social media and technology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and associations with anxiety. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saud, M.; Mashud, M.I.; Ida, R. Usage of social media during the pandemic: Seeking support and awareness about COVID-19 through social media platforms. J. Public Aff. 2020, 20, e02417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. The relationship between burden caused by coronavirus (COVID-19), addictive social media use, sense of control and anxiety. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.A.; Failla, G.; Puleo, V.; Melnyk, A.; Lontano, A.; Ricciardi, W. Social media and attitudes towards a COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review of the literature. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 48, 101454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manata, B.; Bozeman, J. Documenting the longitudinal relationship between group conflict and group cohesion. Commun. Stud. 2022, 73, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrmester, M.; Kwang, T.; Gosling, S.D. Amazon’s mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancy, C.W. COVID-19 and African Americans. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 19, 1891–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 108 | 36.7% |

| Female | 186 | 63.3% |

| Other | ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| White/Anglo/Caucasian/Middle Eastern | 211 | 71.8% |

| Black/African American | 39 | 13.3% |

| Asian | 25 | 8.5% |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 | 0.3% |

| Hispanic or of Latino origin | 15 | 5.1% |

| Other | 3 | 1.0% |

| Job status | ||

| Working full-time | 124 | 42.2% |

| Working part-time | 36 | 12.2% |

| Graduate student | 7 | 2.4% |

| Undergraduate student | 13 | 4.4% |

| Homemaker | 29 | 9.9% |

| Unable to work | 23 | 7.8% |

| Unemployed/Retired | 62 | 21.1% |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Age | (--) | 42.33 | 15.28 | |||||||

| (2) Sex | −0.07 | (--) | -- | -- | ||||||

| (3) Ethnicity | 0.29 | 0.04 | (--) | -- | -- | |||||

| (4) Social media use | −0.31 | 0.02 | −0.25 | (0.85) | 2.85 | 1.38 | ||||

| (5) COVID-19 proximity | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.07 | (--) | -- | -- | |||

| (6) COVID-19 anxiety | −0.16 | 0.18 | −0.03 | 0.16 | 0.17 | (0.85) | 5.08 | 1.62 | ||

| (7) COVID-19 interference | −0.32 | 0.06 | −0.13 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.59 | (0.78) | 4.45 | 1.73 | |

| (8) COVID-19 skepticism | −0.24 | −0.10 | −0.02 | 0.16 | 0.07 | −0.14 | 0.22 | (0.81) | 3.39 | 1.90 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | |

| Age | −0.15 | [−0.27, −0.04] | −0.16 | [−0.27, −0.04] |

| Social media use | 0.08 | [−0.04, 0.19] | 0.07 | [−0.04, 0.18] |

| COVID-19 anxiety | −0.41 | [−0.53, −0.28] | −0.39 | [−0.51, −0.26] |

| COVID-19 interference | 0.39 | [0.25, 0.52] | 0.39 | [0.26, 0.52] |

| Social media use × anxiety | -- | -- | 0.13 | [0.00, 0.25] |

| Social media use × interference | -- | -- | 0.10 | [−0.03, 0.22] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vu, N.C.; Manata, B.; High, A. Exploring the Impact of Personal and Social Media-Based Factors on Judgments of Perceived Skepticism of COVID-19. COVID 2024, 4, 1026-1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4070071

Vu NC, Manata B, High A. Exploring the Impact of Personal and Social Media-Based Factors on Judgments of Perceived Skepticism of COVID-19. COVID. 2024; 4(7):1026-1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4070071

Chicago/Turabian StyleVu, Nhung Cam, Brian Manata, and Andrew High. 2024. "Exploring the Impact of Personal and Social Media-Based Factors on Judgments of Perceived Skepticism of COVID-19" COVID 4, no. 7: 1026-1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4070071

APA StyleVu, N. C., Manata, B., & High, A. (2024). Exploring the Impact of Personal and Social Media-Based Factors on Judgments of Perceived Skepticism of COVID-19. COVID, 4(7), 1026-1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4070071