Abstract

Resilience, the successful process of growth and adaptation in the face of adversity, stress, or trauma, is crucial for optimal well-being. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Latino day laborers (LDLs) faced multiple stressors, making them vulnerable to poor mental health outcomes. Using a cross-sectional study design, we examine the association between situational stressors, mental health, and resilience among LDLs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data included sociodemographic information and measures of situational stressors, mental health (depression, anxiety, and stress), and resilience. Positive and negative resilience subscales were analyzed separately due to a high correlation. A total of 300 male participants completed the surveys, with a mean age of 45.1 years. Almost half had never been married (48%) and had completed nearly eight years of school. The results indicated no significant associations between stressors, positive resilience, and mental health outcomes (B = 0.023, NS) but a significant association between negative resilience, mental health outcomes, and some stressors, such as lack of money (B = 0.103; p < 0.05). The implications of this study include the need to further investigate the use of negatively worded items and how resilience is demonstrated among other vulnerable populations or cultural groups.

1. Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many Latinos in the United States (U.S.), including those who work in healthcare, [1] agriculture, food production [2], and construction [3] were considered essential workers [4]. As such, compared to other populations, Latinos were more exposed to potential COVID-19 infections and were not able to fully apply or enforce recommended mitigation practices, increasing their risk of contracting COVID-19. As a result, even though Latinos make up 18.5% of the population in the U.S. [5], they were disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, representing 27.5% of the total number of COVID-19 cases reported in the U.S. [6].

Research has explored the experiences of Latino workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a focus on agricultural workers who experienced significant impacts at work and at home [2]. Latino day laborers (LDLs), another group of essential workers, faced a greater risk of COVID-19 infection because looking for work at “corners” (e.g., street corners, parking lots, and home improvement stores) requires daily face-to-face contact with other people. Corners are a significant draw for the new Latino immigrants and those who prefer self-employment because they attract other workers as well as potential employers, creating a hub of informal work activity [7]. The unregulated and unpredictable nature of day labor made it difficult to observe mitigation practices at corners and job sites, elevating the risk for COVID-19 infection as well as stress and poor mental health. In addition, economic constraints, such as poor wages, lower household income, and unemployment, further exposed Latinos to COVID-19 infection and mental health problems as they had limited access to preventive healthcare services [8]. Given the confluence of these factors, the ability to cope with adversity and maintain good mental health is critical to understanding the impact of the pandemic on LDLs.

1.1. Resilience

Resilience is the successful process of growth and adaptation in the face of adversity, stress, or trauma [9] and is crucial for the optimal well-being of individuals and populations across their lifespan [10]. Resilience, a dynamic process of positive change in the face of adversity [11], is shaped by interactions between individuals and their environment [12,13]. Resilience is a pattern of adaptive functioning that is multifaced and complex because it involves mobilizing internal and external resources across different systems [14,15]. Resilience is realized when promotive factors, such as individual characteristics, social networks, and positive contextual factors, disrupt the expected trajectory in which exposure to negative risk factors leads to poor outcomes, such as chronic illnesses, poverty, and mental distress [16].

Resilience is the capacity to deal with adversity and recovery. However, it may not always lead to good mental health as the effort may take a psychological toll, particularly in the face of hardships imposed by the structural and social conditions of the context in which people enact their resilient behaviors. According to the minority stress model, individuals from minority groups are exposed to stress in their daily interactions with a social environment that stigmatizes and does not support them [17]. Such scenarios apply to LDLs, whose poverty and precarious social status may have made the adaptations necessary to deal with the conditions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic particularly stressful and challenging.

Even when the literature describes mental health as the assumed outcome of resilient coping, there may be instances in which resilience takes a toll on individuals, worsening their mental health. In the context of work, LDLs take pride in performing dirty, difficult, low-paying, and dangerous jobs, for which the concept of endurance (aguantarse) is critical [18]. By extension, resilience, understood in this way, may be considered a type of endurance that can be applied across situations, but it is dependent on the cultural and contextual aspects of people’s lives [19].

There is limited research on socioecological resilience, i.e., the capacity for absorption and adaptability to disturbance, in regard to expected mental health outcomes [20]. In the socioecological framework, it is possible for the absorption of sudden global shocks and adaptability to chronic stressors to deplete rather than build psychological resources. This depletion may be an outcome among individuals who are already disadvantaged by poverty, discrimination, and weak social capital (e.g., social networks, norms, and trust), for whom resilience represents the ability to overcome adversity without the opportunity for growth. Some research suggests that expecting resilience from vulnerable populations represents an unfair demand and the reification of the status quo as returning to previous conditions of disadvantage does not necessarily represent an improvement in their lives [21]. In this paper, we explore the relationship between resilience and mental health.

1.2. Mental Health

Mental health, a state of emotional and psychosocial well-being that influences perceptions, decision-making processes, and behaviors, occurs across a continuum [22,23]. According to the World Health Organization [24], exposure to socioeconomic adversities, political instability, and contextual hardships, such as the pandemic, exacerbate the risk of experiencing poor mental health. Familism, a cultural emphasis on family relationships as the significant source of emotional and instrumental social support, can be a protective factor in promoting resilience in Latino mental health [25]. In a study by Volpert-Esmond and colleagues [26], familism support was indirectly associated with depression as stronger relationships protect against depression and can have a buffering effect against stress [27]. Although resilience is often confounded with mental health, the capacity to deal with disruptions distinguishes it as a concept [20].

Although there is a correlation between resilience and mental health, the strength of the association varies by the population, setting, risk, and protective factors [28]. In some instances, resilience can shield individuals against severe mental health illnesses [29]. In some vulnerable groups, such as people living with AIDS, lower resilience was linked to those who had higher scores for depression, stress, and anxiety [30]. Studies on children, [31] older adults, [32,33] and people who are living with HIV/AIDS [30] have revealed that resilience improved mental health outcomes and decreased COVID-19-related stress.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a general increase in reported depression and anxiety symptoms due to financial stressors, work-life disruptions, and fear of contracting COVID-19 [34,35]. A few studies showed that individuals with low resilience during the pandemic had higher odds of mental distress compared to highly resilient groups [36,37]. Mayorga and colleagues [38], however, reported a relationship between higher resilience and better COVID-19-related mental health outcomes among Latinos in the U.S. [38]. In a related study conducted in Mexico, researchers found a lower prevalence of depression among healthcare workers who reported medium to high levels of resilience [36]. A study among Latino youth reported an inverse association between pandemic stress, adverse childhood experiences (including mental health problems), resilience, and exposure to COVID-19 [31].

1.3. Stressors

Stressors in the lives of LDLs include threatening conditions, challenges, demands, or structural constraints that burden their individual capacity to cope and can lead to psychological overload [39]. The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have amplified the influence of stressors that typically characterize the pre-pandemic lives of these workers. Significant stressors in the lives of LDLs include those associated with their undocumented status, interpersonal relationships, precarious work and living conditions, discrimination, and social isolation [40,41,42]. LDLs’ inability to secure stable jobs may lead them to share spaces in overcrowded apartments and to experience homelessness when they cannot pay the rent [43]. Working in stressful jobs for which they are not paid or are underpaid can lead to conflicts with family and friends and fights with coworkers [40]. By being away from their families, LDLs can experience social isolation, which also can be self-imposed in cases in which they avoid contact with peers who abuse drugs [41]. These workers are often victims of wage theft and can experience discrimination and mistreatment by people outside their workplace or social network. These stressors represent the structural vulnerability that characterizes their lives and the harsh conditions created by having to adapt to life in the U.S. as immigrants [44,45]. The constant wear and tear created by these cumulative stressors often leads LDLs to experience depression and anxiety [46].

In sum, the literature is sparse in terms of resilience and the impact of stress on the mental health of LDLs. Although there is evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic had adverse effects on mental health, there is limited evidence of the relationship between resilience, mental health, and situational stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic among Latino adults, as well as how these factors are interrelated. Exploring this relationship is particularly important as the COVID-19 pandemic likely exacerbated the stressors that typically characterize their lives. This paper aims to explore the relationship between resilience and mental health, accounting for the situational stressors that LDLs reported during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

Data were collected as part of a rapid needs assessment funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to characterize the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on LDLs in the Houston metropolitan area. All research procedures were approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (HSC-SPH-18-0337).

2.1. Study Setting and Recruitment

Participants were recruited from locations or “corners” where LDLs gathered to seek work, including street corners and parking lots of home improvement and convenience stores. Using a previously developed sampling methodology, locations targeted for recruitment were randomly selected from a list of identified locations compiled by study team members familiar with LDL job-seeking behavior.

Participant recruitment, consent, and interviews were conducted by trained study team members who were fluent in Spanish. LDLs were approached by a member of the study team, who informed them about the purpose of this study. Interested LDLs were then assessed for eligibility. Potential participants were required to be 18 years of age or older, self-identify as Latino, and have a previous history of looking for work at a corner. Non-eligible day laborers were thanked for their time. Eligible laborers were read the informed consent information by a member of the study team and were able to view the consent form on an iPad. Participants were told they could pause the interview if an employment opportunity arose while they were completing it and that they could refuse to answer any survey item. Consent was signified by selecting the appropriate button on the iPad. The survey was then administered by also using an iPad, with the interviewer reading each question to the participant. A sampling quota of 300 participants was set for this study. Recruitment and surveys were conducted in November and December 2021.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Factors

Age was computed as the number of days between the date of the interview and the participant’s date of birth divided by 365 [25]. Marital status was recorded as single/never married; married/living with a partner; divorced; widowed; or separated. Education was measured by the number of years of school completed. Participants were also asked to state the number of years and months they had lived in the U.S.; the number of months was divided by 12 and added to the number of years to obtain the total time spent in the U.S. This value was set to missing if the number of years was not given and was set to the number of years if the number of months was missing. Recent work history was measured by the number of days in the last month the participant found work at the corners. Participants who reported working were asked how much they earned in a typical day. Income in the past month was computed as the product of the number of days worked and typical daily income. Values over $3000 represented outliers and were set to $3000.

2.2.2. Resilience

Resilience was measured by six items from the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) [47]. Three items were positively worded: “You tend to bounce back quickly after hard times”; “It does not take you long to recover from a stressful event”; and “You usually come through difficult times with little trouble”. Three were negatively worded: “You have a hard time making it through stressful events”; “It is hard for you to snap back when something bad happens”; and “You tend to take a long time to get over the setbacks in your life”. Responses were recorded using a four-point scale with 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = agree; and 4 = strongly agree. Negatively worded items were reverse-scored.

The combined resilience scale using the reverse-scored items had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.55, indicating a negative covariance among the items. The reliability for the three positive items was 0.48. The reliability for the three negative items was 0.73. Cronbach’s alpha for the combined scale using (incorrectly) the non-reversed negative items was 0.76. The positive and negative resilience subscales were positively correlated (Spearman’s rho = 0.571, p < 0.001). These results are similar to those reported by Venta and colleagues [48] in their assessment of the use of reverse-coded items in Spanish language surveys.

2.2.3. Situational Stress

Four stressor scales associated with situational stress were previously developed by the research team [44]. The items reflected difficult situations commonly encountered by LDLs and were probed by using the following prompt: “Please tell me how often in the last 30 days …” Responses were recorded using a 3-point rating scale, with 1 = never; 2 = once or a few times (1–3); and 3 = very often (4+). Lack of money consisted of four items (“You didn’t have enough money for your and your family’s most important expenses”). Job deprivation consisted of four items (“You have gone a whole week without getting a job”). Employment concerns comprised six items (“You have been physically or verbally abused by your employer”). Personal concerns consisted of eight items (“Someone has robbed you, your car, or your property”). Cronbach’s alpha of the scale reliability of the situational stress measures was 0.71 for lack of money, 0.57 for job deprivation, 0.79 for employment trouble, and 0.62 for employment trouble.

2.2.4. Mental Health

State anxiety was measured by the six-item Shortened State Trait Anxiety Inventory developed by Perpiñá-Galvañ and colleagues [49]. Items used the stem, “In general today, …” A sample item was “You feel nervous.” A four-point response scale was used, with 1 = not at all; 2 = somewhat; 3 = moderately so; and 4 = very much so. Three items that reflected a positive state (“You feel comfortable”) were reverse-scored. Depression was measured by the 7-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [50]. Items used the stem, “In the last week, how often would you say …?” A sample item was “You didn’t feel like eating; your appetite was poor.” A four-point response scale was used, with 1 = not at all (less than 1 day); 2 = a little (1–2 days); 3 = frequently (3–4 days); and 4 = a lot (5–7 days). Perceived stress was measured by six items from the 14-item instrument developed by Cohen and colleagues [51]. Items used the stem “In the past 30 days, how often have you …?” A sample item was “Been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly.” Responses were recorded using a four-point scale, with 1 = never; 2 = almost never; 3 = sometimes; and 4 = fairly often. For the mental health measures, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87 for depression, 0.73 for anxiety, and 0.88 for stress.

2.3. Data Analysis

Frequencies and percentages were computed for marital status, recoded as single/never married; married/living with a partner; or formerly married (divorced, widowed, or separated). Range, mean, and standard deviation were used for continuous variables, such as age, and for each scale score. Past-month income was rescaled by dividing income by 100 to increase the magnitude of a one-unit increase in income ($100 vs. $1). Scale scores were computed as the sum of each item in the scale. Scale scores were set to missing if responses were missing for any item in the scale. Given the findings reported above regarding the reliability of the positive and negative resilience items, a decision was made to analyze the data using the positive resilience subscale and a negative resilience subscale separately rather than using the combined resilience scale.

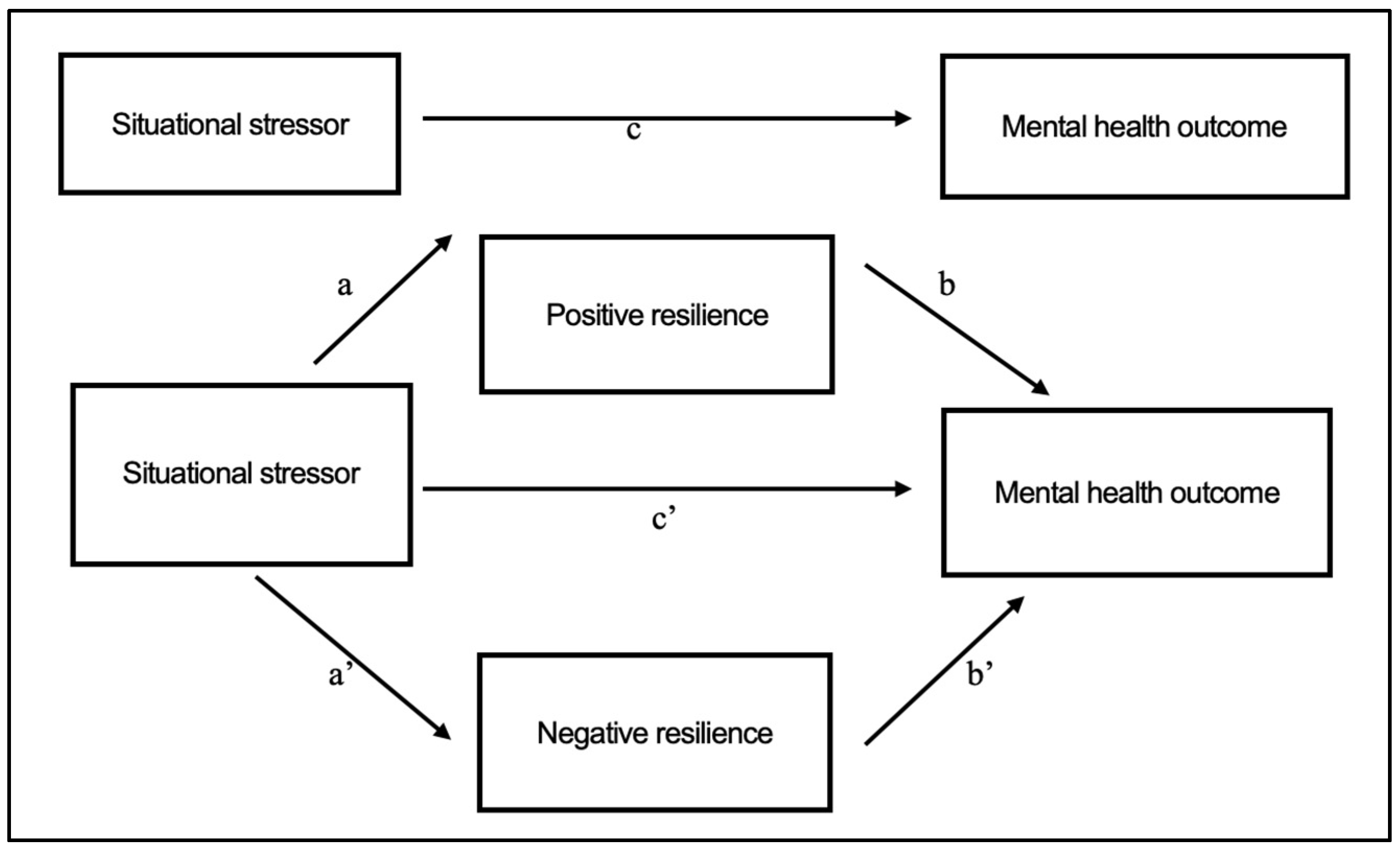

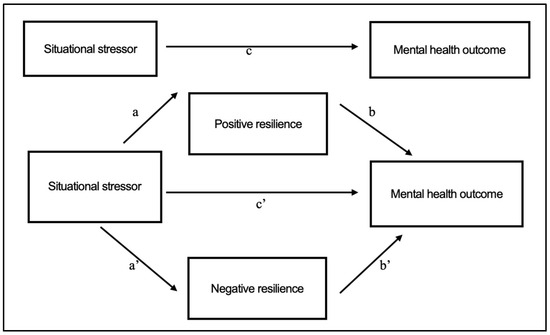

As noted, the study investigators were interested in assessing the associations between measures of situational stress and mental health and whether these associations were mediated by positive and negative resilience. Our parallel mediation model of interest is presented in Figure 1. To assess the model, we applied the product of coefficients approach presented by MacKinnon and colleagues [52]. The direct effect of each situational stressor on the mental health measures was generated by separately regressing each mental health outcome on the situational stressors, resilience measures, and sociodemographic measures considered simultaneously. The direct effect is represented by path c’ in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mediation Model. Total effect: c; Specific indirect effect–positive resilience: a*b; Specific indirect effect–negative resilience: a’*b’; Total indirect effect: Specific indirect effect–positive resilience +; Specific indirect effect–negative resilience; Direct effect: c’; Total effect: Total indirect effect + direct effect.

Indirect effects represent the effect of a given stressor on the mental health outcome via resilience measures. For example, the specific indirect effect of positive resilience consists of the effect of the given situational stressor on positive resilience (path a in Figure 1) and the effect of positive resilience on mental health outcome (path b in Figure 1). The specific indirect effect of positive resilience is then given by the product of the coefficients for the two paths. Similarly, the specific indirect effect via negative resilience was calculated from the coefficients for paths a’ and b’ in Figure 1. The total indirect effect was then equal to the sum of the two specific indirect effects.

The total effect, represented by path c in Figure 1, of a given stressor on a given mental health outcome was equal to the sum of the total direct and indirect effects. Mediation by a given resilience measure is present when a significant indirect effect is observed for that measure. Although the results are presented in terms of “effects,” the data considered here are from a correlational study and are not to be considered causal. Analyses were conducted using SPSS v 29 and Mplus v 8.5. A significance level of p < 0.05 (two-tailed) was used for analyses.

3. Results

Overall, 416 LDLs were observed at 20 locations. Of these, 314 were approached by the field team. Of those approached, 304 consented, and a total of 300 surveys were completed. Analyses were conducted using 278 (92.7%) participants with non-missing responses for each study variable. No differences were found between participants with complete data and those missing data with regard to any of the study variables.

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. On average, participants were in their mid-40s, had been in the U.S. for a little over 13 years, and had completed nearly eight years of school. Participants had earned an average of $925 in the previous month. Almost one-half of all the participants (n = 135, 48.6%) had never been married. Nearly two-fifths (n = 102, 36.7%) were currently married or living with a partner, while the remainder (n = 41, 14.7%) were formerly married.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Latino Day Laborers in Houston, Texas.

3.1. Situational Stressors, Resilience, and Depression

As shown in Table 2, with the exception of employment trouble (path c), there were significant total effects of each of the stressors on depression. Similar results were found for the direct results (path c’). None of the stressors were significantly associated with positive resilience (path a), and positive resilience was not associated with depression (path b). There were no specific indirect effects of positive resilience.

Table 2.

Situational Stressors, Resilience, and Depression.

Lack of money was significantly associated with negative resilience (path a’). Negative resilience was associated with depression (path b’). There was a significant specific indirect effect of lack of money on depression via negative resilience. As such, there was a mediation effect of negative resilience on the effect of lack of money on depression. This effect was partial as the direct effect of lack of money on depression was significant.

3.2. Situational Stressors, Resilience, and Anxiety

As shown in Table 3, with the exception of job deprivation (path c), there were significant total effects of each of the stressors on anxiety. There were significant direct effects of employment trouble and personal concerns on anxiety. The associations between the stressors and positive resilience were non-significant. Positive resilience was not associated with anxiety. There were no specific indirect effects of positive resilience.

Table 3.

Situational Stressors, Resilience, and Anxiety.

The association of lack of money with negative resilience remained. Negative resilience was associated with anxiety. There was a significant specific indirect effect of lack of money on anxiety via negative resilience. As such, there was a mediation effect of negative resilience on the effect of lack of money on anxiety. This effect was complete as the direct effect of lack of money on anxiety was non-significant.

3.3. Situational Stressors, Resilience, and Stress

As shown in Table 4, there were significant total effects of each of the stressors on stress. There were significant direct effects of each situational stressor on stress. As noted, there were no significant paths between the stressors and positive resilience, nor was positive resilience associated with stress. There were no specific indirect effects of positive resilience.

Table 4.

Situational Stressors, Resilience, and Stress.

As mentioned before, lack of money was associated with negative resilience. Negative resilience was associated with stress. There was a significant specific indirect effect of lack of money on anxiety via negative resilience. As such, there was a mediation effect of negative resilience on the effect of lack of money on stress. This effect was partial as the direct effect of lack of money on anxiety was significant.

4. Discussion

This study examined the relationship between measures of situational stress (lack of money, job deprivation, employment concerns, and personal concerns) and mental health outcomes (depression, anxiety, and stress) among LDLs and whether the associations were mediated by a measure of resilience. As detailed, an unexpected, but not unique, situation was encountered during initial analyses, in which responses to items intended to measure the presence of resilience (positive resilience) and items intended to measure a lack of resilience (negative resilience) were positively correlated. Potential item construction problems are discussed below.

Venta and colleagues [48] examined the psychometric properties of four scales, translated into Spanish and administered across four Spanish-speaking samples. The researchers reported that reverse-coded items appeared highly problematic among adult samples (recent immigrants or caregivers for recently immigrated youth). In addition, they reported poor psychometric properties for every instrument investigated as reliability was either improved by excluding reverse-coded items or by including them in an incorrect and un-reversed fashion. The researchers reported problems with reverse-coded items in the scales administered in Spanish and recommended excluding them in Spanish scales. To address the measurement problems reported by Venta and colleagues, the data analyses in the current study were conducted using two separate measures of resilience.

It is important to note that, with the exception of employment concerns, significant total effects were observed for each situational stressor and depression. In addition, with the exception of job deprivation, significant total effects were also observed for each stressor and anxiety. The total effects of each situational stressor on stress were significant. These results confirm that stressors faced by LDLs can adversely affect their mental health.

In considering the potential mediating role of resilience on these effects, no significant paths were observed between the stressors and positive resilience or between positive resilience and mental health outcomes. As noted, the reliability of the positive resilience scale was low (α = 0.48). These findings are atypical and warrant more investigation.

The reliability of the three negative items was considerably higher (α = 0.73) than that of the positive items. Negative resilience was associated with each mental health outcome. Lack of money was significantly associated with negative resilience. From a methodological standpoint, based on the reliability measures, the results obtained in this study suggest that respondents gave more consistent responses across the negative resilience items than they did for the positive items. The results also indicated that higher positive resilience scores correlated with the non-reverse-scored negative items, which warrants further investigation.

Smith and colleagues assessed the reliability of the BRS, noting that resilience was negatively related to perceived stress, anxiety, depression, negative affect, and physical symptoms [47]. The authors concluded that the BRS was more meaningful in addressing resilience as the ability to recover, specifically among people who were already ill, and suggested its use in longitudinal studies. Given the reliability of the BRS across other populations, it is also likely that LDLs are a unique group, and the differences in culture and experiences may have affected the responses. Our results using the BRS also could be due to methods effects, whereby response patterns to the negatively worded items were systematically different from responses to the items on the positive resilience subscale. Other studies on mental health outcomes and coping mechanisms, such as self-esteem, have reported a relationship between negatively worded items and negative affect (or depression) due to a methods effect [53,54]. Given the lack of clarity in regard to the contributing factors, additional research is needed on the use of negatively worded items among already vulnerable populations, whose difficult living conditions possibly align with the negativity expressed with such survey questions.

Resilience, a significant coping mechanism, has sometimes been described as a “weapon of the weak” and a tool used to maneuver, endure, and survive during difficult times with or without resources [55]. Studies among vulnerable populations, including immigrants, have emphasized the role of coping and resilience strategies that have had a positive impact on the health of these populations despite the inequities and hardships they experience [55,56,57]. For example, Eyles and colleagues discussed how individuals who face systemic barriers utilize resilience and agency to cope with and adapt to circumstances [55]. Our current study showed that high levels of COVID-19 stressors, such as lack of money, were associated with low resilience and poor mental health outcomes, which is consistent with other studies. The resilience challenge model proposed by Fergus and Zimmerman [16], whereby individuals exposed to extremely high risks tend to have adverse outcomes [58], may explain why LDLs with negative resilience also had adverse symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress.

Negative resilience partially mediated the effects of lack of money on depression and stress and fully mediated the effects of lack of money on anxiety. It is possible that lack of money may render LDLs particularly vulnerable to poor mental health and that negative (or lack of) resilience may play an important role. Even when the other stressors represent important challenges in their lives, lack of money may play a fundamental role in threatening their survival. Our study did not determine if LDLs in this study had access to other social services. In case of future pandemics, disasters, or emergency situations, social services and public health agencies, along with community-based organizations should collaborate to ensure that LDLs and other populations at risk have access to resources.

Unlike other vulnerable populations who experienced improved mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic due to resilience [11,36], in this study, resilience did not protect LDLs against depression, anxiety, or stress. With the chronic stress experienced by LDLs due to daily challenges and unfriendly work environments [7,59], the additional COVID-19 stressors likely exacerbated the mental health outcomes. As prior studies corroborate unusually poor mental health outcomes among Latino day laborers [46], it is possible that long-term contextual stressors faced by LDLs may have influenced negative resilience in this population, which enables them to survive in dire conditions compared to the general population in the U.S. Longitudinal studies examining trends in mental health outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic reported persistent levels of depression, stress, and anxiety [60,61], suggesting that individuals with prior mental health problems continued throughout the pandemic. With LDLs possibly having higher levels of depression and stress even before the pandemic, subsequent studies should consider conducting prospective studies among LDLs to understand their mental health and stressors over time.

With familism among Latinos, individuals have social capital [25,26] in the form of emotional support, connectedness, and mutual trust, which help cushion against severe mental health [27]. Latino families have social networks and cultural systems that enhance resilience and buffer against negative mental health outcomes [58], where Latino day laborers can thrive despite the overwhelming daily challenges. While our study included married and unmarried individuals, we did not find significant associations between mental health and marital unions/partnerships. This could also be explained by how Latino populations value collective action beyond the nuclear families. Our findings suggest a need for communities to continue supporting individuals within their social networks as a strategy for building resilience and improving social and psychological well-being. These networks could include extended families, friends within the community, churches, community groups, or even online social groups. Researchers could also explore implementation studies within Latino communities with the goal of minimizing situational stressors as a strategy for improving mental health outcomes and fostering resilience.

4.1. Strengths

This study utilized a large sample size and addressed the gap in research on resilience among vulnerable populations. By using standardized scales that measured resilience, mental health, and stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic among LDLs, this study contributes to the growing body of literature on resilience. In addition, this study highlighted positive and negative resilience and the need for further research on how these two dimensions of resilience operate under different exposures.

4.2. Limitations

One of the limitations of this study was the poor reliability of the combined resilience scale using the reverse-scored items. Although Cronbach’s alpha of the negative resilience scale was acceptable and the scale was significantly associated with mental health outcomes, future studies should consider other measures of resilience as being relevant to the experiences of highly vulnerable populations. A cultural and structural revision of this concept would increase the reliability of scales and would utilize reverse scoring, especially when conducting research among Spanish-speaking populations. As a cross-sectional study, causality could not be determined, and the conclusions may not adequately reflect the resilience and mental health conditions among other Latino day laborers. However, the study results provide a snapshot of the associations between the variables, which can be used to enhance further research on stress, resilience, and mental health. Given that responses were based on self-reporting, there is a likelihood of social desirability bias, but this was somewhat mitigated by training researchers to encourage participants to provide honest responses and allowing the participants not to respond if they felt uncomfortable.

5. Conclusions

In sum, our study confirms that individuals who are less resilient tend to have poor mental health outcomes in the face of adverse situational stressors, such as insufficient funds, job loss, employment issues, and personal problems. Different situational stressors were related to specific mental health outcomes, suggesting a need for further studies to examine factors that may exacerbate poor psychological outcomes among resilient individuals. This study also emphasizes the potential role of lowering negative resilience in protecting against depression, anxiety, and stress in the face of situational stressors, such as job deprivation and the lack of money. There is also a need to strengthen supportive networks within families and communities as a strategy for reducing poor mental health outcomes and building resilience among vulnerable populations such as Latino day laborers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.A., A.L. and M.E.F.-E.; methodology, J.A., S.A.A. and M.E.F.-E.; software, J.A.; validation, J.A., S.A.A. and M.E.F.-E.; formal analysis, J.A.; investigation, J.A. and S.A.A.; resources, A.L. and M.E.F.-E.; data curation, J.A. and M.E.F.-E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.A., J.A., A.L. and M.E.F.-E.; writing—review and editing, S.A.A., J.A., A.L. and M.E.F.-E.; visualization, J.A.; supervision, M.E.F.-E.; project administration, A.L. and M.E.F.-E.; and funding acquisition, M.E.F.-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (Grant No. 5R01MD012928). The funders did not have a role in the preparation or publication of this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at Houston—the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) (Approval code: HSC-SPH-18-0337; approval date: 15 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data used in this study, including de-identified participant data and survey results, are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all Latino day laborers who participated in our study despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- González-Gil, M.T.; González-Blázquez, C.; Parro-Moreno, A.I.; Pedraz-Marcos, A.; Palmar-Santos, A.; Otero-García, L.; Navarta-Sánchez, M.V.; Alcolea-Cosín, M.T.; Argüello-López, M.T.; Canalejas-Pérez, C.; et al. Nurses’ perceptions and demands regarding COVID-19 care delivery in critical care units and hospital emergency services. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021, 62, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quandt, A.; Keeney, A.J.; Flores, L.; Flores, D.; Villaseñor, M. “We left the crop there lying in the field”: Agricultural worker experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic in a rural US-Mexico border region. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 95, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asfar, T.; Arheart, K.L.; McClure, L.A.; Ruano-Herreria, E.C.; Dietz, N.A.; Ward, K.D.; Caban-Martinez, A.J.; Samano Martin Del Campo, D.; Lee, D.J. Implementing a Novel Workplace Smoking Cessation Intervention Targeting Hispanic/Latino Construction Workers: A Pilot Cluster Randomized Trial. Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 48, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellon-Lopez, Y.M.; Carson, S.L.; Mansfield, L.; Garrison, N.A.; Barron, J.; Morris, D.A.; Ntekume, E.; Vassar, S.D.; Norris, K.C.; Brown, A.F.; et al. “The System Doesn’t Let Us in”—A Call for Inclusive COVID-19 Vaccine Outreach Rooted in Los Angeles Latinos’ Experience of Pandemic Hardships and Inequities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musu-Gillette, L.; Robinson, J.; McFarland, J.; KewalRamani, A.; Zhang, A.; Wilkinson-Flicker, S. Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups (NCES 2016-007); National Center for Education Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 188. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED567806 (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Olayo-Méndez, A.; Vidal De Haymes, M.; García, M.; Cornelius, L.J. Essential, Disposable, and Excluded: The Experience of Latino Immigrant Workers in the US during COVID-19. J. Poverty 2021, 25, 612–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Esquer, M.E.; Ibekwe, L.N.; Guerrero-Luera, R.; King, Y.A.; Durand, C.P.; Atkinson, J.S. Structural Racism and Immigrant Health: Exploring the Association Between Wage Theft, Mental Health, and Injury among Latino Day Laborers. Ethn. Dis. 2021, 31 (Suppl. 1), 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.A.; Thierry, A.D.; Pendergrast, C.B. The Devastating Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Older Black and Latinx Adults: Implications for Health and Well-Being. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2022, 77, 1501–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. The Road to Resilience. Resilience. 19 April 2018. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Tsai, J.; Freedland, K.E. Introduction to the special section: Resilience for physical and behavioral health. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.; Jordan, R. Recognizing Resilience: Exploring the Impacts of COVID-19 on Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. Gend. Issues 2022, 39, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.D.; Bonanno, G.A.; Sinan, B. A brief retrospective method for identifying longitudinal trajectories of adjustment following acute stress. Assessment 2015, 22, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PeConga, E.K.; Gauthier, G.M.; Holloway, A.; Walker, R.S.; Rosencrans, P.L.; Zoellner, L.A.; Bedard-Gilligan, M. Resilience is spreading: Mental health within the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S47–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, G.L.; Salcido, V.; Gomez Alvarado, C. Resilience in the Time of COVID-19: Familial Processes, Coping, and Mental Health in Latinx Adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2024, 53, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazargan-Hejazi, S.; Ambriz, M.; Ullah, S.; Khan, S.; Bangash, M.; Dehghan, K.; Ani, C. Trends and racial disparity in primary pressure ulcer hospitalizations outcomes in the US from 2005 to 2014. Medicine 2023, 102, e35307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, S.; Zimmerman, M.A. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2005, 26, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.M.; Meyer, I.H. Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 51, 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo, L.M.; Morales, M.C. Masculinities narratives and Latino immigrant workers: A case study of the Las Vegas residential construction trades. In Exploring Masculinities; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 239–264. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266408687_Masculinities_narratives_and_Latino_immigrant_workers_A_case_study_of_the_Las_Vegas_residential_construction_trades (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Ungar, M. Resilience across cultures. Br. J. Soc. Work 2008, 38, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Quintero, C.; Avila-Foucat, V.S. Operationalization and measurement of social-ecological resilience: A systematic review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.H. Anti-resilience: A roadmap for transformational justice within the energy system. Harv. Civ. Rights-Civ. Lib. Law Rev. 2019, 54, 1–48. Available online: https://journals.law.harvard.edu/crcl/wp-content/uploads/sites/80/2019/03/Baker.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsko, R.H.; Claussen, A.H.; Lichstein, J.; Black, L.I.; Jones, S.E.; Danielson, M.L.; Hoenig, J.M.; Jack, S.P.D.; Brody, D.J.; Gyawali, S.; et al. Mental Health Surveillance Among Children—United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Suppl. 2022, 71, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization.(WHO). Mental Health. 17 June 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Lugo Steidel, A.G.; Contreras, J.M. A New Familism Scale for Use with Latino Populations. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2003, 25, 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpert-Esmond, H.I.; Marquez, E.D.; Camacho, A.A. Family relationships and familism among Mexican Americans on the U.S.-Mexico border during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2023, 29, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona, K.; Campos, B.; Chen, C. Familism is associated with psychological well-being and physical health: Main effects and stress-buffering effects. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2017, 39, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheshlagh, R.G.; Sayehmiri, K.; Ebadi, A.; Dalvandi, A.; Dalvand, S.; Maddah, S.B.; Tabrizi, K.N. The relationship between mental health and resilience: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2017, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaian, T.; De Anstiss, H.; Antoniou, G.; Baghurst, P.; Sawyer, M. Resilience and Its Association with Depression, Emotional and Behavioural Problems, and Mental Health Service Utilisation among Refugee Adolescents Living in South Australia. Int. J. Popul. Res. 2012, 2012, 485956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaraldi, G.; Milic, J.; Barbieri, S.; Marchiò, T.; Caselgrandi, A.; Volpi, S.; Aprile, E.; Belli, M.; Venuta, M.; Mussini, C. Resilience and Frailty in People Living with HIV During the COVID Era: Two Complementary Constructs Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2022, 89 (Suppl. 1), S65–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’costa, S.; Rodriguez, A.; Grant, S.; Hernandez, M.; Alvarez Bautista, J.; Houchin, Q.; Brown, A.; Calcagno, A. Outcomes of COVID-19 on Latinx youth: Considering the role of adverse childhood events and resilience. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, P.A.; Hurst, A.; Johnson, J.; Tarrier, N. Psychological resilience in young and older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, H.; Kurth, M.L.; Lee, H.S.; Choun, S.; Lee, D.; Aldwin, C.M. Resilience in Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Socioecological Approach. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2022, 77, E64–E69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Wykes, T.; Galderisi, S.; Nordentoft, M.; Crossley, N.; Jones, N.; Cannon, M.; Correll, C.U.; Byrne, L.; Carr, S.; et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020, 7, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñacoba, C.; Velasco, L.; Catalá, P.; Gil-Almagro, F.; García-Hedrera, F.J.; Carmona-Monge, F.J. Resilience and anxiety among intensive care unit professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs. Crit. Care 2021, 26, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand-Arias, S.; Carmona-Huerta, J.; Aldana-López, A.; Náfate-López, O.; Orozco, R.; Cordoba, G.; Alvarado, R.; Borges, G. Resilience and risk factors associated to depressive symptoms in Mexican healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Salud Pública México 2023, 65, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riehm, K.E.; Brenneke, S.G.; Adams, L.B.; Gilan, D.; Lieb, K.; Kunzler, A.M.; Smail, E.J.; Holingue, C.; Stuart, E.A.; Kalb, L.G.; et al. Association between psychological resilience and changes in mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayorga, N.A.; Nizio, P.; Garey, L.; Viana, A.G.; Kauffman, B.Y.; Matoska, C.T.; Zvolensky, M.J. Evaluating resilience in terms of COVID-19 related behavioral health among Latinx adults during the coronavirus pandemic. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2023, 52, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheaton, B.; Montazer, S. Stressors, stress, and distress. In A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contexts, Theories, and Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 171–199. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=b8f921b900eff8ec6e072948e3fbc95d86a75add#page=193 (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Galvan, F.H.; Wohl, A.R.; Carlos, J.A.; Chen, Y.T. Chronic Stress Among Latino Day Laborers. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2015, 37, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, N.J. Identifying psychosocial stressors of well-being and factors related to substance use among Latino day laborers. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2011, 13, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organista, K.C.; Arreola, S.G.; Neilands, T.B. Depression and Risk for Problem Drinking in Latino Migrant Day Laborers. Subst. Use Misuse 2017, 52, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, M.R.; Bourdeau, B.; Hovey, J.D. Day laborers and occupational stress: Testing the Migrant Stress Inventory with a Latino day laborer population. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2010, 16, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Esquer, M.E.; Gallardo, K.R.; Diamond, P.M. Predicting the Influence of Situational and Immigration Stress on Latino Day Laborers’ Workplace Injuries: An Exploratory Structural Equation Model. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, J.; Hart, L.K.; Bourgois, P. Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Med. Anthropol. 2011, 30, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.M.; Williams, E.C.; Ornelas, I.J. Help Wanted: Mental Health and Social Stressors Among Latino Day Laborers. Am. J. Men’s Health 2019, 13, 1557988319838424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venta, A.; Bailey, C.A.; Walker, J.; Mercado, A.; Colunga-Rodriguez, C.; Ángel-González, M.; Dávalos-Picazo, G. Reverse-Coded Items Do Not Work in Spanish: Data from Four Samples Using Established Measures. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 828037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perpiñá-Galvañ, J.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J.; Richart-Martínez, M. Reliability and validity of shortened state trait anxiety inventory in Spanish patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Am. J. Crit. Car 2013, 22, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.Z. Evaluating the seven-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale short-form: A longitudinal US community study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2136404 (accessed on 3 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fairchild, A.J.; Fritz, M.S. Mediation analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, C.; Motl, R.W. Further investigating method effects associated with negatively worded items on self-report surveys. Struct. Equ. Model. 2006, 13, 440–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindwall, M.; Barkoukis, V.; Grano, C.; Lucidi, F.; Raudsepp, L.; Liukkonen, J.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. Method effects: The problem with negatively versus positively keyed items. J. Personal. Assess. 2012, 94, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyles, J.; Harris, B.; Fried, J.; Govender, V.; Munyewende, P. Endurance, resistance and resilience in the South African health care system: Case studies to demonstrate mechanisms of coping within a constrained system. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.; Chun, Y.; Hamilton, B.; Roll, S.; Ross, W.; Grinstein-Weiss, M. Coping with COVID-19: Differences in hope, resilience, and mental well-being across U.S. racial groups. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Scully, J.; Hart, T. The paradox of social resilience: How cognitive strategies and coping mechanisms attenuate and accentuate resilience. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 25, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.B.; Thompson, S.J. Common themes of resilience among latino immigrant families: A systematic review of the literature. Fam. Soc. 2010, 91, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, S.B.; Chaney, E.H.; Bethel, J.W. Stress, depression and coping among Latino migrant and seasonal farmworkers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 1815–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gori, A.; Topino, E. Across the COVID-19 Waves; Assessing Temporal Fluctuations in Perceived Stress, Post-Traumatic Symptoms, Worry, Anxiety and Civic Moral Disengagement over One Year of Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P.; Shevlin, M.; Murphy, J.; McBride, O.; Fox, R.; Bondjers, K.; Karatzias, T.; Bentall, R.P.; Martinez, A.; Vallières, F. A longitudinal assessment of depression and anxiety in the Republic of Ireland before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 300, 113905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).