Abstract

In the past decade, mRNA vaccines have been highly discussed as a promising therapy for cancer. With the pandemic of COVID-19, some researchers redirected their studies to the development of a new vaccine for COVID-19 due to the urgent need. With the pandemic’s deceleration due to the vaccines’ success, the research and development of mRNA vaccines have turned to cancer again. Considering the new evidence and results generated by the vaccination of millions of people with mRNA vaccines, this article intends to provide a perspective on how the results from COVID-19 vaccination could now provide new insights for the development of an mRNA cancer vaccine. Many lessons were learned, and new evidence is available to re-focus and enhance the potential of the mRNA technology to cancer. Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna’s mRNA technologies, and their significant advancements, allowed mRNA to overcome many of the challenges and blockers related to this platform in the past, now providing a new breadth of hope on using the mRNA technology to treat many diseases, namely cancer. This study also reports a better understanding of how it was possible to boost an accelerated development process of COVID-19 vaccines from a regulatory point of view. It is also relevant to consider other synergies and factors that contributed to gathering all the conditions ensuring the development of these vaccines in such a short period. Suppose the same efforts from all stakeholders could be applied to the development of new cancer vaccines, aligned now with the new scientific evidence generated from the current mRNA vaccines for COVID-19. In that case, mRNA cancer vaccines are near, and a new era for cancer treatment is about to begin.

1. Introduction

The pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been assigned as a serious threat to public health which also led to a social and economic crisis in the world. It was the cause of millions of deaths and also caused many constraints in the world’s style of living. The development of a safe and effective vaccine was urgent to the ensure the global health and to bring back the sense of normality to everyone.

It is important to understand that vaccines hold a global health success history as they assumed control over many infectious diseases and therefore millions of deaths are avoided per year. Vaccination has eradicated smallpox, reduced global child mortality rates, and prevented countless birth defects and lifelong disabilities such as polio and rubella. A lot of diseases can be prevented by vaccines [1]. Along with clean water, sanitation, and antibiotics, vaccines are one of the greatest public health achievements. This is why vaccine hesitancy is now one of the ten threats to global health according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [2].

However, the development of the vaccines has always faced some challenges related with the pathogens and diseases themselves and the population (since it is hard to reach some individuals, infants, pregnant women, immunocompromised persons, or older adults). Additionally, challenging circumstances are also related to emerging infections, epidemics, and pandemics as these are linked to a raise in pressure and concerns. Therefore, new strategies have been developed to overcome these challenges: new antigens, new antigen presentation (eg., DNA, mRNA), new delivery strategies (e.g., live vectors), and new adjuvants [3,4].

In terms of development timelines, the history of vaccines is interesting as it is undeniable how over the years it has been possible to shorten the time of the development. For varicella, it took 25–30 years to develop a vaccine [5]. For Ebola, it took 5 years [6] and for COVID-19 it took 1 year [7,8]. It is worth to question how it was possible to accelerate this process and why for other diseases, such as cancer, for which there are no adequate treatment options available, similar efforts could not be done in the same way. The answer to this question is implicit in the word Pandemic. Governments, social media, and the world population was looking at a vaccine to prevent SARS-CoV-2. Competition within the pharmaceutical industry together with their investors boosted this development, along with pro-active actions from the side of the agency regulators such as the EMA and FDA who provided strategies on how to accelerate the process through rolling reviews and expedited programs for COVID-19 to allow a progressive and urgent support to the Marketing Authorization Holders (MAH) [8,9,10]. Furthermore, some aspects related to the vaccine itself were already established from previous outbreaks of SARS-CoV in 2003 and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012. Both coronavirus and SARS-CoV-2 belong to the family Coronaviridae. Various studies concluded that SARS-CoV-2 is 80% genetically identical to SARS-CoV. Therefore, the selection of spike protein as the antigen target was well supported by previous studies and lessons from these two coronaviruses [11,12]. In addition, the prefusion stabilization strategy was also previously developed and established for the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) MERs vaccines [13,14]. It is also important to highlight that the vaccines from BioNTech/Pfizer and Moderna were both nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccines. This kind of platform has been studied in vaccine development for other infectious diseases such as RSV, influenza, and dengue. The incorporation of modified nucleosides into mRNA reduces the immunogenicity and improves the stability and translational capacity of mRNA, making this technology feasible as a vaccine delivery platform [15,16,17]. Additionally, it is important to consider that the first approved vaccines reflect the new strategies that have been developed to overcome some challenges of older vaccines and were already being developed to treat other diseases. This means that the technology was already being established and it just needed to follow another direction. This is the case of the mRNA vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna [8,9,18].

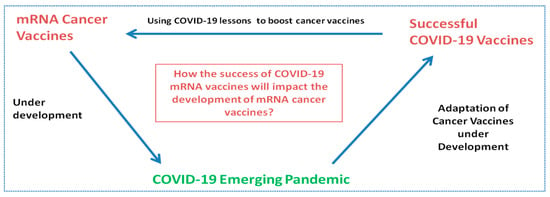

To better understand the strategy behind cancer and mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, it is important to highlight basic concepts of immunology. This study will allow the readers to understand how vaccines being developed for cancer were successfully applied into COVID-19 and how this success may now impact the continuation of the development of cancer vaccines (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Influence and relationship in the development of mRNA cancer vaccines and mRNA vaccines.

2. Search Strategy

2.1. Data Collection Process for COVID-19 Vaccines

Since many studies have been published since the start of the pandemic, it was needed to provide the details on how this data collection was conducted. It is important to highlight and recognize that due to multiple publishing of studies related to COVID-19, selecting the relevant articles can be a challenge and a limitation if not done properly.

Therefore, exhaustive research was conducted in the main scientific databases, namely Web of Science and Pubmed, where the most prominent articles were analyzed. Three main criteria were considered for the article’s selection: number of citations, impact factor of the journal, and article year. Considering the amount of uncertainty in the earlier published studies for COVID-19, articles from 2019 were discarded and only articles from 2021 and 2022 were considered. In case the evidence was acceptable, articles from 2020 were considered. The EMA, FDA, and CDC websites were also considered.

This literature selection allowed the generation of different sets of data to produce the results presented and analyzed in this work.

For the research conducted at Web of Science and Pubmed, the combination of the terms “COVID-19 vaccine” on the title with “development” and “technolog *” on the fields were used. On Pubmed, the combination of the terms “COVID-19” + “vaccine” + “strategy” + technology” filtered under systematic review was also used.

To make sure the most accurate scientific evidence was prioritized, only articles from journals under Q1 were considered and some Q2 were considered acceptable.

A medicine search was conducted at the EMA website applying the filter “COVID-19” for the ‘medicine type’ category in order to find the European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs) for all the centrally authorized vaccines. This search reflected the status of the EMA repository on the 02.02.2022. The results were reviewed individually to collect the information within the European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs) for each vaccine.

The EPARs were analyzed to consult the details of the clinical studies conducted during phases I and III of their clinical development and the respective regulatory achievements. The full list of indications and the dosage for each vaccine were taken from the EPARs for the EU products. For US products, the FDA and CDC websites were consulted to collect this kind of information.

2.2. Data Collection Process for mRNA Cancer Vaccines

To collect data related with mRNA cancer vaccines, the Web of Sciences and Pubmed were also used together with ClinicalTrials.gov. In Clinical Trials.gov, research was conducted using the three following terminologies and results were gathered afterwards: “mRNA cancer vaccine”, ”mRNA oncology vaccine”, and “mRNA tumor vaccine”. Articles and data from any date in time were considered in this case. The intention for this is to be able to understand what was being developed for mRNA vaccines prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, how the pandemic was able to influence new mRNA studies, and what were the most researched technology platforms on mRNA vaccines for cancer prior and after the pandemic.

For the research conducted at Web of Science and Pubmed, the combination of the terms “mRNA vaccine” on the title with “cancer”, was used. On Pubmed, the combination of the terms “mRNA” + “vaccine” + “cancer” was used.

To make sure the most accurate scientific evidence was prioritized, only articles from journals under Q1 were considered and some Q2 could be considered acceptable.

2.3. Data Collection for Immunology Concepts

To collect data for basic immunology concepts, both Web of Sciences and Pubmed were used.

In the Web of Sciences, the term “Immunology” was applied and filtered by “Highly cited papers”. This allowed a good level of confidence to the researchers considering that these were all highly citated articles, and among these only those from journals under Q1 were considered and some Q2 were also considered acceptable.

For the Pubmed research, the term “Immune system cells” was searched following the same rational and only journals under Q1 were considered and some Q2 were considered acceptable. The British Society for Immunology website was consulted to complement immunology concepts.

3. Data Analysis and Study Limitations

Study limitations can be associated with selection of the best studies considering the impact factor. Publications evolved rapidly since the pandemic and selectivity of the studies had to be rigorous. Regarding mRNA cancer vaccines under development, we have access only to information that is publicly available. The published results do not reflect the truth in the universe of mRNA cancer vaccines under development since pharmaceutical companies might be developing their vaccines and might be in a research phase or in a pre-clinical phase and therefore nothing is yet available to the public. Additionally, ongoing studies in any of the phases (I, II, II) could have been abandoned or not published due to poor results.

4. Results

4.1. Immunology Concepts

Before analyzing the results, it is important to briefly address some basic concepts of immunology. The development of vaccines against a new pathogen or a tumor highly demands an understanding on how the immune system enhances protection [4].

The immune system should protect us from infection through various lines of defense [19]. It is linked into a complex and interactive network of lymphoid organs, cells, humoral factors, and cytokines [20]. These complex interactions must be balanced since any perturbance may cause disease. When underactivity of the immune system occurs, it may result in severe infections and tumours of immunodeficiency, while when overactivity occurs, it may result in allergic and autoimmune disease [20].

The immune system has been divided into two main subsystems: the innate system and the adaptive system [20,21]. Both the innate and adaptive immunity include humoral components (e.g., antibodies, complement proteins, and antimicrobial peptides) and cell-mediated components (that involve the activation of phagocytes and the release of various cytokines) [21].

The term innate immunity includes physical (i.e., skin, saliva), chemical, and microbiological barriers and provides immediate defense [20]. It is considered to be non-specific in terms of response as it based on a large family of pattern recognition receptors. In other words, it can be said that the responses are the same for all potential pathogens, despite the differences they may have [21].

The adaptive immune response is specific as it depends on distributed receptors for certain specific antigens. This means that cells are able to distinguish between and respond differently to a variety of antigens. The adaptive immune system focuses on the lymphocytes’ role to fight these pathogens [21].

Therefore, it can be said that the antigen-specific reactions through T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes triggers the adaptive system responses [20].

It is important to highlight that the innate response is rapid, but it may damage the normal tissues due to the lack of specificity. On the other hand, the adaptive response is precise, but can take days or weeks to develop. However, any defect in either innate or adaptive system can lead to immunopathological disorders such as autoimmune diseases [22]. From this perspective, adaptive immunity could also damage healthy tissues if it is directed to an undesirable target such as self-protein, as it occurs in autoimmune diseases [23]. It is consistent across many studies that the adaptive response has memory, which means that further exposure leads to a more determined and faster response [20].

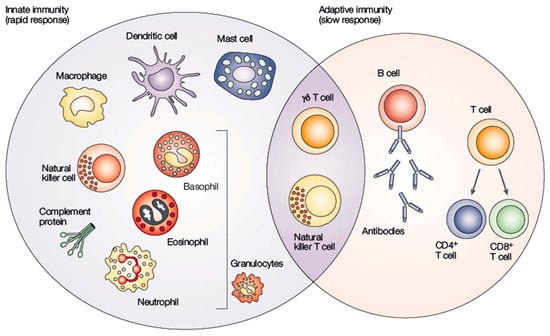

Despite the solid acknowledgment of these basic immunology concepts across many studies, some recent results have provided insights about the innate immune memory, which can be associated with macrophages or NK cells, and this requires a continuous research in the field of immunology [21,24]. Figure 2 illustrates the components involved in the adaptive and innate immune systems and how they interact.

Figure 2.

Interaction between innate and adaptive immune systems. Adapted from [25].

Cells from innate immunity are generated by myeloid lineage cells and mature into monocytes, macrophages, erythrocytes, platelets, and granulocytes, providing the first line of defense. Cells from the adaptive immune system come from lymphoid progenitor cells and provide natural killer (NK) cells, B-cells, and T-cells that are responsible for the second line of defense against pathogens and other abnormalities [26].

Magrophages and denditric cells (DC) from the innate immune system can recognize external antigens through pattern recognition receptors and trigger naive CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells, respectively, from the adaptive immune system [27]. The triggering of CD4 or CD8 depends on whether the epitope (part of antigen) is presented by MHC-I or MHC-II. MHC-I can be found in any human cells, and the recognition and presentation of epitope is restricted by MHC-I trigger CD8 T-cells. MHC-II molecules are only presented in neutrophils, macrophages, and DC (the so-called antigen-presenting cells) presented epitopes to CD4 T-cells [28]. Additionaly, professional antigen-presenting cells (APC) interact with T-cells using positive and negative feedback systems by producing cytokines. These cytokines, and other mediators such as hormones, and other antigens will stimulate the innate immune system to produce either IL-12 or IL-4 in the local microenvironment around a newly activated T cell. This so called native Th0 lymphocytes may be differentiated into T helper type 1 (Th1) cells when they are activated in a microenvironment rich in IL-12 or can be inhibited from developing into Th1 cells in case the microenvironment is rich in IL-4, IL-10, or other substances such as corticosteroids and catecholamines. In fact, the same naïve Th0 cells, if exposed to IL-4, will differentiate into T helper type 2 (Th2) cells. However, exposure of naive Th0 cells to IL-12 inhibits polarization to Th2 cells. It is important to understand that when both IL-4 and IL-12 are present upon activation of naive T-cell, the effects of the IL-4 will dominate, and a type 2 response will ensue.

Th1 stimulates type 1 immunity, which is characterized by intense phagocytic activity and Th2 cells stimulate type 2 immunity, which is characterized by high antibody titers. Type 1 and type 2 immunity do not have the exact same meaning to cell-mediated and humoral immunity, since Th1 cells can also be responsible for enhancing moderate levels of antibody production and Th2 cells actively suppress phagocytosis.

In the majority of infections, type 1 immunity is considered to be protective, and type 2 responses will assist with the resolution of cell-mediated inflammation [29].

A non-randomized open-label phase I/II trial in healthy adults, 18–55 years of age in study from 2020, involving the mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 (BNT162b1) demonstrated that the vaccine induces CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in most of the participants, with Th1 polarization of the helper response [30]. There are much more interactions and cascades that trigger interaction between both systems and the purpose of this short summary is to highlight that there are many molecular and cellular mechanisms that connect both innate and adaptive immunity. [27]

Therefore, the most important concept to be retained in this section is that the immune system is very complex and that the innate and the adaptive systems cooperate with each other to ennhance protection [21].

Other concepts that are important to retain in this chapter are the innate immune responses against mRNA vaccines and similar and different immune responses between infectious diseases and cancer.

4.1.1. Innate Immune Responses against mRNA Vaccines

The innate immune system represents the first line of immune response against mRNA vaccination. During the vaccination, the mRNA is recognized by various pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) which are responsible for producing IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines [31].

The mRNA binding PRRs can be classified into cytosolic PRRs and endosomal PRRs. In the cytosol, the PRRs include the nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs) and the RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), while inside the endosomes, the PRRs are represented by the toll-like receptors (TLRs). Once they recognize mRNA, a cascade of interactions and signaling pathways is initiated, leading to the production of the IFNs and pro-inflammatory cytokines as explained above [32].

Therefore, mRNA not only encodes an antigen, but it also has intrinsic immune-stimulating activity that is responsible to contribute to vaccine efficacy and support the intended therapy. It can be considered a self-adjuvant effect. mRNA vaccination can bring this additional innate immune stimulation. However, this additional immunogenicity should be carefully controlled and balanced to ensure the safety of the therapy, as it may result in side effects of having flu-like symptoms or risk of autoimmune diseases [32].

To sum up, the optimal innate immune response and inflammatory cytokine release are crucial to enable T- and B-cell immune responses. However, in case there are excessive innate immune responses, they might lead to cytokine storms and damage of the tissue. This is why the induced immune response by mRNA should be controlled but at the same time should retain antibody production [31].

At the moment, the approved mRNAs vaccines by the EMA and FDA are effective at preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection and have fortunately overcome previous limitations related with this platform and were able to reflect the potential of this technology.

4.1.2. Differences and Similarities across Immune Responses between Infectious Diseases and Cancer

As already described, the immune system is able to provide protection against tumors and pathogens. For many years, it was established a close relationship between the immune system and its capability on fighting infectious diseases. This has not happened in the cancer field and only more recently immune system has been explored and studied in cancer, leading immediately to the recent successes of immunotherapy.

Today, it is unquestionable that the control of the immune system is a key approach in treating and preventing both infectious diseases and cancer [33].

Regarding the similarities between cancer and infectious diseases in terms of immunology, it is important to acknowledge that generalizations should be carefully done due to diversity of both infectious agents and cancers. However, it is a fact that there are similar immunological mechanisms across both pathologies, and the study of the link between these two therapeutic areas should be continued [33].

Tumor cells have to develop mechanisms to be able to evade the immune system and infectious agents also have to overcome the body barriers and immune mechanisms.

Both diseases may share the fact of having reduced expression of class I MHC molecules, being then able to escape from our proctective cytotoxic T-cells. Both tumor cells and infections will prevent access to immune mechanisms [34].

Therefore, it is known that innate and adaptive immunity are activated by both infections and tumors. Regarding this similarity and also the fact that the way immune cells infiltrate infected tissues share the same way to infiltrate neoplastic tissues, it is important to understand that their function in the first setting is quite different in both diseases. This is because infected tissues are represented by an acute inflammatory environment that develop the generation of protective immunity. These acute infections are usually associated with evident inflammation. On another hand, tumors are represented by chronic inflammation that suppresses antitumor immune responses and promotes tumor growth, escaping from the immune system. Therefore, neoplastic lesions will induce initially a low inflammatory landscape or immune reaction, which means that only after tissue destruction based on tumor expansion, inflammation and tissue repair will become evident [35]. In fact, it is well known that the chronic inflammation associated with certain persistent infections, for instance, those caused by H. pylori or human papilloma virus (HPV), are believed to be an important cause of the gastric and cervical cancers associated with these agents. They not only cause cancer but inflammation caused by these infectious also contribute to the morbidity and mortality of cancer [33].

This means that a wide understanding of how the immune system successfully responds to pathogens may lead to the design and implementation of strategies to replicate common responses to tumors. Therefore, it is very important to have present some concepts immunology in cancer and infectious diseases as knowledge and advancements in both fields may influence each other in achieving successful treatments for both diseases. It is known, for instance, that studies of infection led to cancer immunotherapies (checkpoint immunotherapies, CAR-T, vaccines, therapeutic targeting of PRRs) and that success of cancer immunotherapy may also be applied to infectious disease and are already being exploited [33].

4.2. Vaccine Techonologies for SARS-CoV-2 Candidates

Many factors contributed to the immediate success of implementing new technologies on COVID-19 vaccines leading to their fast development. The main regulatory agencies implemented rapid scientific advice and rolling review methods that allowed the development to progress in a fast pace [36,37].

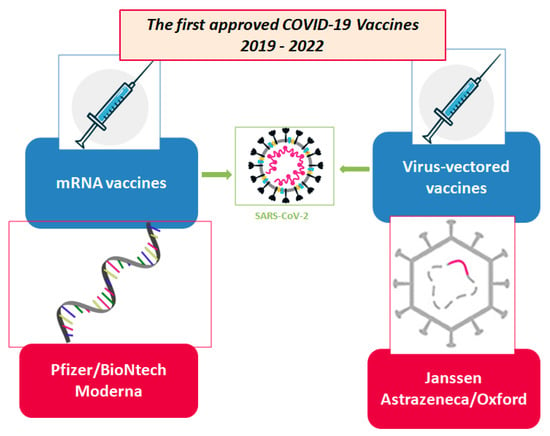

The first approved vaccines for COVID-19 can be seen in Figure 3 and information about their indications and dosage are compiled in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Technologies for SARS-CoV-2 first generation of vaccine candidates. Adapted from [4].

Table 1.

Principal data for four vaccines to COVID-19 about indications and dosage.

4.3. mRNA Platform for Vaccines—Advantages and Disadvantages

One of the most important challenges related with the mRNA technology has been associated with the delivery system, the instability, and the excessive immunogenicity [47].

However, because of its potential, the scientists continued their research and development and during the past decades, especially more recently, progresses were made in the safety, efficacy, and production of mRNA vaccines [47,48].

The hope reflected in the mRNA technology for vaccines is related to the several advantages it represents. mRNA is precise as it will only express a specific antigen and induce a directed immune response, unlike attenuated or inactivated vaccines. Furthermore, it promotes both humoral and cellular immune response and induces the innate immune system. mRNA is more effective when comparing to DNA-based vaccines since it does not need to enter the nucleous of the cells and it has no chance of performing any random genome integration. Additionally, mRNA is quickly degraded by cellular processes, with no traces found after 2–3 days. In fact, this is also one of its disadvantages, due to the fact of mRNA being related with a lot of instability.

Another positive point is related with its manufacturing. A change in the encoded antigen does not affect the mRNA backbone physical–chemical characteristics, and since production is based on an in vitro cell-free transcription reaction, safety concerns that are found in other technologies are minimized since the presence of cell-derived impurities and viral contaminants are not common [49].

The first approved mRNA vaccines in the world are the vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 [48]. The approval of these vaccines in the EMA came through the conditional approval procedure. The Pfizer’s Vaccine Comminarty was granted conditional approval on 21 December 2020 [40] and Spikevax (previously Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine) for COVID-19 was granted conditional approval on 2021 [41].

The legal basis of conditional marketing authorization procedure is defined under the Article 14-a of Regulation (EC) No 726/200 and the provisions for granting a conditional marketing authorisation are further elaborated in Regulation (EC) No 507/2006. This procedure establishes that, under very specific and duly authorized conditions, for certain medicines addressing unmet medical needs and that are the interest of public health, the grant of conditional approval can be based on less comprehensive clinical, pharmaceutical, or non-clinical data than normally required, where the benefit of immediate availability of the medicine outweighs the risk inherent in the fact that additional data are still required. These authorisations are valid for one year and can be renewed annually. The marketing authorisation holder must fulfil specific obligations within defined timelines and the authorization can be converted into a standard marketing authorisation once all obligations (such as completing ongoing or new studies or collecting additional data) are fulfilled and the complete data confirms that the benefits outweigh the risks. The EMA can take any regulatory action, such as suspending or revoking the marketing authorisation, in case the benefits no longer outweigh the risks [50].

Now, since the approval of these mRNA vaccines and its administration in millions of people, more information about safety and efficacy has become available, and those technology platforms have been validated [51,52].

Overall, there are two major types of mRNA technology for vaccines: non-replicating mRNA and virally derived, self-amplifying RNA. The first encodes the antigen of interest and contains 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs), while the self-amplifying RNAs encode not only the antigen but also the viral replication machinery that enables intracellular RNA amplification and abundant protein expression [53].

In terms of delivery platforms, it is important to understand that mRNA has to cross the cell membrane to reach the cytosol. This is a very challenging step due to mRNA characteristics such as having a large size (300–5000 kDA) and being prone to degradability. Therefore, it was needed to overcome this limitation [49]. The solution is to deliver mRNA using the right strategy. A proper delivery system will enable mRNA vaccines to achieve full therapeutic mRNA [48]. There are many ways to deliver mRNA: naked mRNA with direct injection; conjugation with lipid-based carriers, polymers, or peptides; via transfection of dendritic cells (DC); through viral vectors; and many other platforms [48,49].

4.4. mRNA Cancer Vaccines

When developing cancer vaccines, it is also very important to consider a proper adjuvant. This will boost and promote inflammation at the delivery site, facilitating immune cell recruitment and activation. Other important points that should be considered are related to the choice of the targeting antigen, the timing of vaccination, manipulation of the tumor environment, and the combination with other treatments that might cause additive or even synergistic anti-tumor effects [51].

Due to mRNA characteristics already described above and the fact that the molecule is also negatively charged, naked RNA is prone to nuclease degradation and has difficulty in crossing the cell membrane [48].

Table 2 reflects the results from the data collection research at Clinical Trials. Gov, aiming to find all clinical trials related to mRNA vaccines for cancer.

Table 2.

ClinicalTrials.gov Search Results from 30 April 2022 for all mRNA-based cancer vaccines.

According to the gathered data (Table 2), it was possible to verify that the most used strategy to load mRNA in cancer vaccines was through dendritic Cells (DC).

Dendritic cells (DCs) are considered the “professional” antigen-presenting cells of the immune system. They are capable of stimulating novel or enhancing existing anti-tumor immune responses. To achieve this result, DCs need to present antigenic peptides and provide co-stimulatory signals, similar to those provided by CD80/CD86 and CD70 or cytokines such as IL-12p70 [54]. DCs can be loaded with RNAs by endocytosis. This process can be improved by electroporation. External loading of DCs will enable and facilitate efficient targeting of antigen presenting cells.

According to Table 2, in the most recent clinical trials, it is possible to verify that other strategies have started to become being developed and implemented such as monocytes loaded with mRNA, neoantigens, liposomes (nanoparticles), and also neo-adjuvants.

These new technologies will help naked RNA to be injected through a carrier. These carriers will improve RNA stability and uptake. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are now one of the most promising delivery systems. They are easy to produce and they are safe [51].

From Table 2, it is also possible to conclude that these recently new technological platforms have been studied more recently after the COVID-19 pandemic. This conclusion is supported by the nine clinical trials from November 2019 to May 2022. By filtering in the table the word “dendritic”, 25 results appear from March 2002 to September 2021. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that clinical trials with mRNA vaccines for cancer have been developed prior to the pandemic focusing more on dendritic cells vaccines and more recently other delivery systems are being developed. This trend on lipid nanoparticles might be based on the validated platforms from Pfizer and Moderna’s mRNA vaccine since both used lipids to help the mRNA enter the cells as reflected in Table 1.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

There is huge hope for mRNA technology vaccines in cancer due to success of these vaccines in COVID-19. Platforms have been validated and safety and efficacy data are available. It is therefore needed to engage with the new data available to continue the development and the improvement of mRNA cancer vaccines.

From the regulators, investors, and government side, it is also very important that all these stakeholders recognise that if the same efforts could be applied to the development of mRNA vaccines in oncology, then we could say that improvements in the development of successful mRNA cancer vaccines could be expected and a new era for cancer treatment is possibly about to begin.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.V.; formal analysis, L.S. and N.V.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S.; writing—review and editing, L.S. and N.V.; supervision, N.V.; project administration, N.V.; funding acquisition, N.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by FEDER—Fundo Europeu de Desenvolimento Regional through the COMPETE 2020—Operational Programme for Competitiveness and Internationalization (POCI), Portugal 2020, and by Portuguese funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, in a framework of the projects in CINTESIS, R&D Unit (reference UIDB/4255/2020) and within the scope of the project “RISE—LA/P/0053/2020”. N.V. also thanks support from the FCT and FEDER (European Union), award number IF/00092/2014/CP1255/CT0004 and CHAIR in Onco-Innovation at FMUP.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

N.V. also thanks support the FCT and FEDER (European Union), award number IF/00092/2014/CP1255/CT0004 and CHAIR in Onco-Innovation from FMUP.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Greenwood, B. The contribution of vaccination to global health: Past, present and future. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- WHO. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Dai, T.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, M.; Zhou, F. A systematic review of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, L.; Gao, G.F. Viral targets for vaccines against COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 21, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Varicella. In Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, J.; Bruno, S.; Eichberg, M.; Jannat, R.; Rudo, S.; VanRheenen, S.; Coller, B.A. Applying lessons from the Ebola vaccine experience for SARS-CoV-2 and other epidemic pathogens. Npj Vaccines 2020, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, K.; Sitar, S.; Graham, B.S.; Mascola, J.R. Accelerated COVID-19 vaccine development: Milestones, lessons, and prospects. Immunity 2021, 54, 1636–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, P. The lightning-fast quest for COVID vaccines—And what it means for other diseases. Nature 2020, 589, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgin, E. How COVID unlocked the power of RNA vaccines. Nature 2021, 589, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythgoe, M.P.; Middleton, P. Comparison of COVID-19 Vaccine Approvals at the US Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, and Health Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2114531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadi, F.; Pal, D.; Sarma, J.D. Spike Glycoprotein Is Central to Coronavirus Pathogenesis-Parallel Between m-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Ann. Neurosci. 2021, 28, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgujar, K.C.; Badgujar, V.C.; Badgujar, S.B. Vaccine development against coronavirus (2003 to present): An overview, recent advances, current scenario, opportunities and challenges. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 1361–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Du, L.; Jiang, S. Learning from the past: Development of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 19, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, T.P.; Chou, H.T.; Hu, R.; Bzymek, K.P.; Correia, A.R.; Partin, A.C.; Li, D.; Gong, D.; Wang, Z.; Yu, X.; et al. Enhancing the Prefusion Conformational Stability of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Through Structure-Guided Design. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 660198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandker, S.S.; Godman, B.; Jawad, I.; Meghla, B.A.; Tisha, T.A.; Khondoker, M.U.; Haq, A.; Charan, J.; Talukder, A.A.; Azmuda, N.; et al. A Systematic Review on COVID-19 Vaccine Strategies, Their Effectiveness, and Issues. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, E.; Liu, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Song, L.; Zhu, B.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, D.; Li, Y. Advances in COVID-19 mRNA vaccine development. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granados-Riveron, J.T.; Aquino-Jarquin, G. Engineering of the current nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 111953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DDolgin, E. Unlocking the potential of vaccines built on messenger RNA. Nature 2019, 574, S10–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- British Society for Immunology, What Is Immunology? Available online: https://www.immunology.org/public-information/what-is-immunology (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- PParkin, J.; Cohen, B. An overview of the immune system. Lancet 2001, 357, 1777–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftimie, R.; Gillard, J.J.; Cantrell, D.A. Mathematical Models for Immunology: Current State of the Art and Future Research Directions. Bull. Math. Biol. 2016, 78, 2091–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall, J.S.; Warrington, R.; Watson, W.; Kim, H.L. An introduction to immunology and immunopathology. Allergy, Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2018, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y. NLRP3 Inflammasome: Checkpoint Connecting Innate and Adaptive Immunity in Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 732933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, E.R.; Burelbach, K.R.; McBride, M.A.; Stothers, C.L.; Owen, A.M.; Hernandez, A.; Patil, N.K.; Williams, D.L.; Bohannon, J.K. Innate Immune Memory and the Host Response to Infection. J. Immunol. 2022, 208, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dranoff, G. Cytokines in cancer pathogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat. Cancer 2004, 4, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haseeb, M.; Anwar, M.A.; Choi, S. Molecular Interactions Between Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Their Therapeutic Implications. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, T.; Kitamura, H.; Iwakabe, K.; Yahata, T.; Ohta, A.; Sato, M.; Takeda, K.; Okumura, K.; Van Kaer, L.; Kawano, T.; et al. The interface between innate and acquired immunity: Glycolipid antigen presentation by CD1d-expressing dendritic cells to NKT cells induces the differentiation of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 2000, 12, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wieczorek, M.; Abualrous, E.T.; Sticht, J.; Álvaro-Benito, M.; Stolzenberg, S.; Noé, F.; Freund, C. Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) Class I and MHC Class II Proteins: Conformational Plasticity in Antigen Presentation. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spellberg, B.; Edwards, J.E., Jr. Type 1/Type 2 Immunity in Infectious Diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 32, 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Muik, A.; Derhovanessian, E.; Vogler, I.; Kranz, L.M.; Vormehr, M.; Baum, A.; Pascal, K.; Quandt, J.; Maurus, D.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T-cell responses. Nature 2020, 586, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ryu, J.-H. Influenza Viruses: Innate Immunity and mRNA Vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 710647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnaert, A.-K.; Vanluchene, H.; Verbeke, R.; Lentacker, I.; De Smedt, S.C.; Raemdonck, K.; Sanders, N.N.; Remaut, K. Strategies for controlling the innate immune activity of conventional and self-amplifying mRNA therapeutics: Getting the message across. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 176, 113900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, R.E.; Eichberg, M.J.; Portnoy, D.A.; Raulet, D.H. Listening to each other: Infectious disease and cancer immunology. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2, eaai9339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benharroch, D.; Osyntsov, L. Infectious Diseases Are Analogous With Cancer. Hypothesis And Implications. J. Cancer 2012, 3, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinchieri, G. Cancer Immunity: Lessons From Infectious Diseases. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 212, S67–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- EMA. COVID-19 Vaccines: Development, Evaluation, Approval and Monitoring. 2020. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/vaccines-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines-development-evaluation-approval-monitoring (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Marinus, R.; Mofid, S.; Mpandzou, M.; Kühler, T.C. Rolling Reviews During COVID-19: The European Union Experience in a Global Context. Clin. Ther. 2022, 44, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/Pfizer-BioNTech.html (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- CDC. Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/Moderna.html (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- EMA. EPAR Comirnaty. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/comirnaty (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- EMA. EPAR Spikevax. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/spikevax (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- EMA. EPAR Vaxzevria. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/vaxzevria-previously-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- AstraZeneca, A.B. Summary of Product Characteristics, Vaxzevria. 2021. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/vaxzevria-previously-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- EMA. EPAR COVID-19 Vaccine Janssen. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/covid-19-vaccine-janssen (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- CDC. Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/janssen.html (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Janssen-Cilag International, N.V. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/covid-19-vaccine-janssen-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, J.; Han, X.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. mRNA vaccine: A potential therapeutic strategy. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, C.; Sharma, A.R.; Bhattacharya, M.; Lee, S.-S. From COVID-19 to Cancer mRNA Vaccines: Moving From Bench to Clinic in the Vaccine Landscape. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 679344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, S.S.; Prazeres, D.M.F.; Azevedo, A.M.; Marques, M.P.C. mRNA vaccines manufacturing: Challenges and bottlenecks. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2190–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conditional Marketing Authorisation, EMA. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/marketing-authorisation/conditional-marketing-authorisation (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Heine, A.; Juranek, S.; Brossart, P. Clinical and immunological effects of mRNA vaccines in malignant diseases. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, N.; Weissman, D.; Whitehead, K.A. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: Principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Porter, F.W.; Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines—A new era in vaccinology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benteyn, D.; Heirman, C.; Bonehill, A.; Thielemans, K.; Breckpot, K. mRNA-based dendritic cell vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2015, 14, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).