Assessing Participation: Toward Long-Term Experiences, Trajectories and Maturity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Recurring Difficulties in Assessing Participation

2.2. Multiple Criteria for Assessing Participation

2.3. Contemporary Issues when Assessing Participation

3. Research Questions

- When applied longitudinally over long periods of time, what do evaluation criteria teach us about participation (its successes and failures) in terms of outputs, outcomes, and processes?

- Looking at various participatory trajectories (from both organizing agencies and participants), is there any level of participation maturity emerging over time, which could contribute to participation enhancement?

4. Cases’ Presentation

4.1. Context of the Participatory Initiative

- Workshop W1 invites citizen participants to contribute to the planning step, which defines the goal of participation, the recruitment strategy and the topic to be addressed through the process;

- Workshop W2 explores the needs, problems, desires, and priorities of the participants in relation to the topic chosen at the end of workshop W1;

- Workshop W3 brings out ideas in response to the needs and concerns identified in workshop W2. During this stage, the participants first formulate their ideas freely, together select a few of them and then summarize those under the form of project sheets. These project sheets are eventually synthesized through short video clips which are submitted as “challenges” to the hackers participating in the next stage;

- The fourth step of the process is the generation of concrete prototypes and therefore requires professional expertise (in design, architecture, IT development, management, communication, etc.). We call on the teams of the “Citizens of Wallonia” hackathon organized in Wallonia (by FuturoCité with the support of the Walloon Region) from 6 to 8 March 2020, only one week before the COVID lockdown in Belgium;

- Workshop W4 aims to present the prototypes developed during the hackathon to the citizens and to collect their feedback.

4.2. Key Results of the Participatory Initiative

- The number of participants involved: the more participants, the higher the number of challenges. Indeed, we divided all the citizens present in workshops W3 into tables of four to eight people, each table working on a specific topic. Since each table proposed a video clip with a project sheet, it is quite logical to obtain more ideas from City B than from City C;

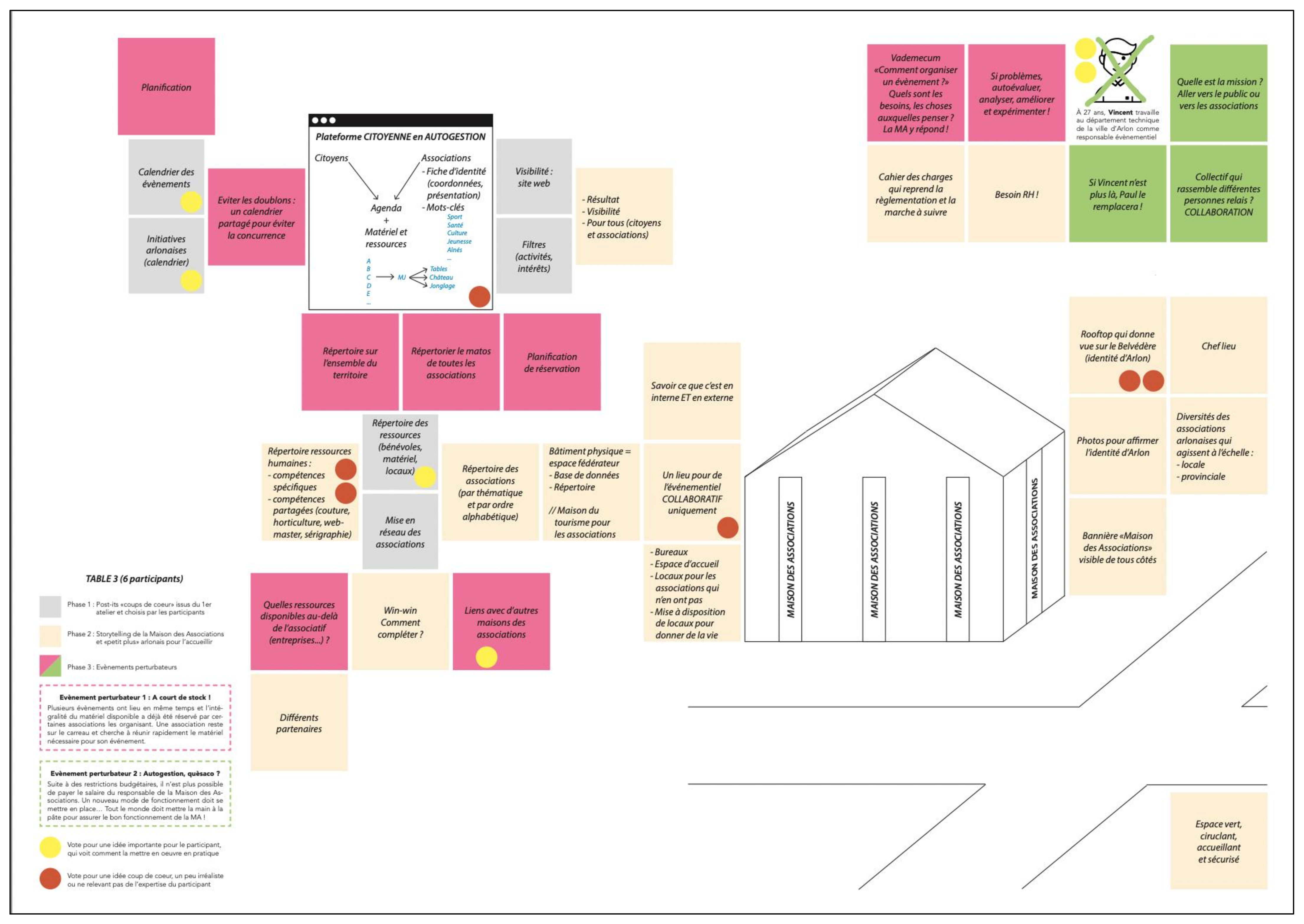

- The level and nature of motivation. The level of creativity and therefore the number of ideas proposed is often directly related to the intrinsic or extrinsic nature of the participants’ motivation [40]. For example, participants from City B are intrinsically motivated by the “house for associations” project and are full of ideas to improve a situation that affects them closely. Conversely, participants from City C were very difficult to recruit, and some of the municipal employees were only present because they were forced to be. Their relationship to the project is therefore completely different, as they just wanted to fulfill their professional duty and not to satisfy a personal interest;

- The nature of the proposed ideas. The technological or analogical connotation of the suggested challenges impacted the choice of the hackers. For example, the students from City-D school instinctively turned to mobile applications to address their mobility issue. On the contrary, City-A citizens gave a lot of thought to the layout of the future cultural center building. Not all of their ideas could therefore be retained for the hackathon, even though they were still obviously transferred to the city to pursue the project.

5. Methodology

5.1. Data Collection

- The small size of the initial sample, particularly in Cities C and D where the total number of persons involved (n) was, respectively, 17 and 23 (compared to 62 and 78 in Cities A and B);

- The last-minute withdrawals of seven people out of the 19 who initially confirmed their participation in the focus groups;

- The relatively high average age of the participants in Cities A and B, some of whom (n = 5) told us that they wanted to take part in the discussion but were unable to master the necessary digital tools;

- The postponement of the focus groups from April to September, who were organized too late after the previous stages and thus attracted lower interest.

5.2. Data Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Preliminary Results from the Logbook

6.2. In-Depth Results from the Focus Groups

6.2.1. Participants’ Evaluation of the Process

“We went in blind, not really knowing if we would like it.”(D1)

“I expected to be in front of a group of politicians who asked us ‘here, what do you think?’ about a project that is already much more concrete.”(A1)

“This process was sometimes surprising (…) At the beginning, I was a bit skeptical… All these games… In the end, it came together, we got out of it!”(B2)

“What I felt was this desire to bypass mediation by the elected official, to go directly to the citizen.”(B3)

“In the end, given that there is no constraint for the decision-makers or for the people who hold the budget, the probability that the thing will remain a dead letter is quite high.”(B3)

“Between the number of parents who said ‘we’ll come’ and the number who actually came, (…) it was a quarter.”(D2)

“We all have hectic lives, it’s not easy to free up time”.(C1)

“That’s maybe the regret, there weren’t a lot of people”.(A1)

6.2.2. Participants’ Evaluation of the Outcomes

“Well, in relation to the application, I wouldn’t have done it so…”(C3)

“I think it was just better that you were the one who took the decisions. (…) It gave us good guidance so that we didn’t do things that were unfeasible.”(D1)

“The main ideas came from us. (…) The two computer experts who passed around the tables were there to answer our questions but not to impose their ideas.”(D1)

“At the first session, I was a bit scared… I thought: ‘What are they going to ask me? Will I be up to it?’ But no, it went very well.”(B2)

6.2.3. Participants’ Evaluation of the Outputs

“I’m glad that there were concrete, realized projects, that we weren’t always talking about ‘blah blah blah’. There was a result at the end thanks to the hackathon team.”(B4)

“It’s a very nice result for two–three days [of hackathon]. It wasn’t their idea in the first place, they had to make our idea their own.”.(D1)

“It’s a shame because in a way we all want to get involved, at first we think ‘oh nice’ and then in the end ‘oh no, as usual in (City A), there is nothing’”(A1)

“From the university’s side, it was clear that there was no guarantee that the ideas would find concretization, as it was a wider project.”(A2)

“They were really in their own world, it’s not like we were working together with them. These were our ideas, we could have accompanied them at least for some time.”(D1)

“The problem was that the ideas were a bit theoretical, and in my opinion, they did not lead to practical implementation.”(A2)

“Architects have a budget… We also dreamed of beautiful things and, if it were up to us, we would have a new building. But we realize that we have to see what is available.”(B2)

- In City B, a building is eventually going to be transformed to accommodate the house for associations; funds have already been released to hire a part-time “house manager” and the city is in contact with the Solution-B1 winning team to find funding;

- In City A, the cultural center project will probably take place, a design office has already proposed some sketches of the ground plans, but the results of the participatory approach will perhaps not be integrated, especially as no project was pushed forward during the hackathon;

- In Cities C and D, the projects will not take place because the hackathon team members were all students who abandoned their project due to the COVID-19, lack of time and funding.

7. Discussion

- When the first participatory initiative is organized in a city, the level of satisfaction is high and the level of expectation is low, because the novice participants are enthusiastic about discovering something new and do not know what to expect;

- As similar initiatives are repeated, participants refine their expectations, sharpen their demands and are no longer as satisfied with some of the elements they enjoyed in the first initiative. The level of satisfaction of those “insiders” decreases as their expectations increase;

- If recurrent initiatives differ in terms of tools and methods, participants experiment with a new way of participating, whose originality or novelty for their city may generate a peak of satisfaction and a stabilization in terms of expectations;

- If these initiatives in turn become recurrent, the participants become more intransigent again and increasingly picky about the quality of the participatory process.

8. Conclusions

- Announce the objectives of each workshop at the time of recruitment, on top of communicating the overall objective, so that each activity matches the expectations of participants;

- Not to rush into too many activities and to devote the necessary time to the process, without going into too many details, to achieve the objectives naturally;

- Share the results obtained at each stage of the process in order to avoid loss of confidence among the participants and their weariness with processes that do not lead to anything;

- Adapt the protocol to the level of expertise of the participants and manage the heterogeneity of the group to minimize disappointments and misunderstandings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siva, J.P.S.; London, K. Investigating the role of client learning for successful architect-client relationships on private single dwelling projects. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2011, 7, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biau, V.; Fenker, M.; Macaire, E. Les métiers de l’architecture et de l’urbanisme à l’épreuve de l’implication des habitants et des usagers. In Cahier Ramau 6 L’Implication des Habitants dans la Fabrication de la Ville Métiers et Pratiques en Question; Biau, V., Fenker, M., Macaire, E., Eds.; Cahiers Ramau: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Prost, R.; Chaslin, F. Pratiques de Projet en Architecture: Le Tournant Silencieux: Essai; Infolio: Gollion, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Albrech, J. Towards a theory of participation in architecture—An examination of humanistic planning theories. J. Archit. Educ. 1988, 42, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaire, E. Des architectes à l’épreuve de la participation. In Ville Éphémère, Ville Durable—Nouveaux Usagers, Nouveaux Pouvoirs; De Coninck, F., Deroubaix, J.-F., Eds.; L’oeil D’or: Cannes, France, 2009; pp. 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell, J.; Lloyd, P. Beyond specification: A study of architect and client interaction. Des. Stud. 2014, 35, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E. Information, Inspiration and Co-creation. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of the European Academy of Design, Bremen, Germany, 29–31 March 2005; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, D. Professional-Client discourse in design: Variation in accounts of social roles and material artifacts by designers and their clients. Text Interdiscip. J. Study Discourse 1996, 16, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadoin, O. La ville des individus. Sociologie, urbanisme et architecture, propos croisés. In Villes et Entreprises; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zetlaoui-Léger, J. Urbanisme participatif. In Dictionnaire Critique et Interdisciplinaire de la Participation; Casillo, I., Barbier, R., Blondiaux, L., Chateayraynaud, F., Fourniau, J.-M., Lefebvre, R., Neveu, C., Salles, D., Eds.; GIS Démocratie et Participation: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harrop, D. “Let’s make a prototype”: Exploring temporary urbanism in the form of transitional urban design schemes that can be tested prior to permanent implementation. In Proceedings of the Empowering Change—Transformative Innovation Sin and Projects: Book of Proceedings of the 8th International Urban Design Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 15–16 November 2015; Association for Sustainability in Business Inc.: Brisbane, Australia, 2015; pp. 124–146. [Google Scholar]

- Barcenilla, J.; Bastien, J.-M.-C. L’acceptabilité des nouvelles technologies: Quelles relations avec l’ergonomie, l’utilisabilité et l’expérience utilisateur ? Trav. Hum. 2009, 72, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lallemand, C.; Gronier, G.; Koenig, V. User experience: A concept without consensus? Exploring practitioners’ perspectives through an international survey. Comput. Human Behav. 2015, 43, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevaldson, B. Beyond user centric design. In Proceedings of the RSD7, Relating Systems Thinking and Design 7, Turin, Italy, 23–26 October 2018; pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Davidova, M.; Zavoleas, Y. Post-anthropocene: The Design after the Human Centered Design Age. In Proceedings of the 25th CAADRIA Conference, Bangkok, Thailand, 5–6 August 2020; Holzer, D., Nakapan, W., Globa, A., Koh, I., Eds.; Chulalongkorn University: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; West, J. Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cardon, D. Innovation par l’usage. In Enjeux de Mots. Regards Multiculturels sur les Sociétés de L’Information; Ambrosi, A., Peugeot, V., Pimienta, D., Eds.; C&F Editions: Caen, France, 2005; pp. 309–341. [Google Scholar]

- Steen, M. Tensions in human-centred design. CoDesign 2011, 7, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, R. Learning to talk to users in participatory design situations. Des. Stud. 2007, 28, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjögvinsson, E.; Ehn, P.; Hillgren, P.-A. Design things and design thinking: Contemporary participatory design challenges. Des. Issues 2000, 28, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, N.; Shabak, M.; Embi, M.R.B.; Khan, T.H. The Architect, the Client and Effective Communication in Architectural Design Practice. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roux, M. Inventer Un Nouvel Art D’habiter. Le Ré-Enchantement de L’espace; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Faburel, G. L’habitant et les savoirs de l’habiter comme impensés de la démocratie participative. Cah. RAMAU 2013, 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J. Occupying Architecture. Between the Architect and the User; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B.; Yaneva, A. “Give me a gun and i will make all buildings move”: An ANT’s view of architecturearchitecture. In Explorations in Architecture: Teaching, Design, Research; Geiser, R., Ed.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Linden, V.; Dong, H.; Heylighen, A. Tracing architects’ fragile knowing about users in the socio-material environment of design practice. Des. Stud. 2019, 63, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chess, C. Evaluating environmental public participation: Methodological questions. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2000, 43, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klüber, S.; Maas, F.; Hohm, A.; Hurtienne, J. Participant’s View: Short-Term Evaluation of Realizing PD Ideals. PervasiveHealth Pervasive Comput. Technol. Healthc. 2020, 2, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drain, A.; Shekar, A.; Grigg, N. Insights, Solutions and Empowerment: A framework for evaluating participatory design. CoDesign 2021, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelson, J.; Gauvin, F.-P. Assessing the Impacts of Public Participation: Concepts, Evidence and Policy Implications; Canadian Policy Research Networks: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. Evaluating public-participation exercises: A research agenda. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2004, 29, 512–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossen, C.; Dindler, C.; Iversen, O.S. Evaluation in Participatory Design: A literature survey. ACM Int. Conf. Proc. Ser. 2016, 1, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurian, L.; Shaw, M.M. Evaluation of public participation: The practices of certified planners. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2009, 28, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosener, J. User-oriented evaluation: A new way to view citizen participation. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1981, 17, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webler, T. “Right” Discourse in Citizen Participation: An Evaluative Yardstick. In Fairness and Competence in Citizen Participation: Evaluating Models for Environmental Discourse; Renn, O., Webler, T., Wiedemann, P., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 35–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, N.; Slegers, K.; Duysburgh, P. Codesign with people living with cognitive or sensory impairments: A case for method stories and uniqueness. CoDesign 2015, 11, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundmark, S. Design project failures: Outcomes and gains of participation in design. Des. Stud. 2018, 59, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, V.; van der Does, R. Should we care about small-scale deliberation? A systematic literature review of minipublic consequences. In Proceedings of the Kongress der Deutschen Vereinigung für Politikwissenschaft, Frankfurt, Germany, 25–28 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, E.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, M.A.; Amabile, T.M. Motivation and creativity. In Handbook of Creativity; Sternberg, R.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 297–312. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K.; Kendall, L. The focused interview. Am. J. Sociol. 1946, 51, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J. The triangle of engagement: An unusual way of looking at the usual suspects. Public Money Manag. 2007, 27, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amabile, T.M. Social environments that kill creativity. In Readings in Innovation; Gryskiewicz, S.S., Hills, D.A., Eds.; Center for Creative Leadership: Colorado, NC, USA, 1992; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

| City | City A | City B | City C | City D | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic | A cultural center on the main square | A house for associations | Eco-friendly behaviors and smart meters at the household level | Mobility in the surroundings of one specific school | / |

| Number of workshops | 3 (W1–W2–W3) | 4 (W1–W2–W3–W4) | 2 (W2–W3) | 3 (W1–W2–W3) | 12 |

| Total number of participants (N) 1 | 79 | 103 | 18 | 33 | 233 |

| Total number of persons (n) 1 | 62 | 78 | 17 | 23 | 180 |

| Total number of logbook entries | 76 | 85 | 15 | 27 | 203 |

| City | City A | City B | City C | City D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mainly seniors and some people in their thirties | Mainly people over 50 | From 30-year-old to 60-year-old people | Mainly 16-year-old and 17-year-old students |

| Socioeconomic profile | Working-class and retired people | Working-class and retired people | Vulnerable people and municipal staff | Students, school parents and teachers |

| Thematic profile | Culture amateurs or producers; municipal actors | Associative network and active neighbors | People with ecological or/and economical concerns | Users of the school and mobility facilities in the surrounding area |

| ID | City | Citizens’ Challenge | Hackers’ Solution | Possible Awards | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | City A | An algorithm to transform music into images and to ornament a facade | Projects 1 to 5 were not selected by hackers | ||

| 2 | City A | An interactive tool for designing modular spaces | |||

| 3 | City B | A platform to centralize associative information | |||

| 4 | City B | A solution to make the house for associations a convivial and multi-purpose place | |||

| 5 | City B | An inter-association coordination platform | |||

| 6 | City B | A material and human resources management platform | Solution B1 | Best prototype Best citizen service Best solution for “smart territories” | Still active: the application is evolving and the team is looking for funding |

| 7 | City B | A system for managing access and occupation of the house for associations | Solution B2 | [Omitted for blind review] Prize | Abandoned in November 2020 due to lack of funding |

| 8 | City C | An interface to visualize energy consumption | Solution C | / | Abandoned at the end of the hackathon, as these were student projects that did not have the means to invest in the long term, especially in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic |

| 9 | City D | An application to encourage soft mobility from/to home/school | Solution D1 | Best Pitch | |

| 10 | City D | A co-biking application to go to school | Solution D2 | / | |

| Types of Questions | Questions |

|---|---|

| Relationship to citizen participation | Short, open-ended questions: |

| How did you find out about the workshop? | |

| What motivated you to participate in this workshop? | |

| Have you ever participated in another participatory event (apart from this one)? If so, what was it about? | |

| Do you intend to participate again in this project? Why or why not? | |

| Evaluation of the participatory experience | How would you rate your participation? Indicate your feelings by ticking one option per line (very low–low–moderate–high–very high): |

| Your motivation to participate | |

| Your contribution to the project | |

| Your decision-making power | |

| Your understanding of the objectives of the day | |

| Your confidence that the project will succeed | |

| Your confidence in the organizers | |

| Your overall satisfaction | |

| Benefits of the participatory experience | What benefits do you get from your participation? Check the one that best describes your experience (not at all—a little—moderately—a lot—I don’t know): |

| New knowledge | |

| New skills | |

| Cohesion between participants | |

| Awareness of new issues | |

| Recognition of your contribution | |

| Degree of commitment to the project | |

| Other comments | Short, open-ended questions: |

| What did you particularly like about your participation? | |

| What did you find disappointing or annoying? | |

| In your opinion, what objectives should ideally be achieved at the end of the participatory process? | |

| Any comments? A question? Express yourself here. |

| Timing | Instructions and Questions |

|---|---|

| 0′–5′ | Objectives of the meeting |

| 5′–15′ | Round table presentation |

| 15′–20′ | Reminder of the stages of the participatory process and presentation of the results from the hackathon |

| 20′–60′ | In your own words, what were the objectives of the participatory workshop(s) you attended? |

| Did this (these) workshop(s) meet your expectations? | |

| Do you feel that your contribution has had/will have an impact on the final project? | |

| Do you think that you can contribute to the future of the project? | |

| Are you satisfied with the decisions that were made? | |

| What do you think are the benefits of your participation for the city? | |

| What do you think about taking part in other participatory initiatives in the future? |

| Cities | Workshop 1 | Workshop 2 | Workshop 3 | Hackathon | Workshop 4 | Whole Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City A | N = 18 S = 4.4 | N = 33 S = 3.7 | N = 28 S = 4.0 | / | / | N = 79 S = 4.0 |

| City B | N = 48 S = 4.1 | N = 25 S = 4.0 | N = 26 S = 4.1 | / | N = 4 | N = 103 S = 4.1 |

| City C | / | N = 8 S = 3.9 | N = 10 S = 3.6 | / | / | N = 18 S = 3.8 |

| City D | N = 10 S = 4.4 | N = 12 S = 4.3 | N = 8 S = 4.3 | N = 3 | / | N = 33 S = 4.4 |

| Cities | “Novices” = No Previous Participation 1 | “Insiders” = Only One Previous Participation | “Usual Suspects” = Frequent Participation |

|---|---|---|---|

| City A | n = 26 (61%) | n = 13 (30%) | n = 4 (9%) |

| City B | n = 20 (53%) | n = 10 (26%) | n = 8 (21%) |

| City C | n = 6 (43%) | n = 2 (14%) | n = 6 (43%) |

| City D | n = 13 (56%) | n = 8 (35%) | n = 2 (9%) |

| In general | n = 65 (55%) | n = 33 (28%) | n = 20 (17%) |

| Cities | Participant 1 | Average Satisfaction | Participatory Background | Participatory Trajectory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| City A | A1 | High | Insider | 2 participations (W2–W3) |

| A2 | High | Novice | 1 participation (W3) | |

| City B | B1 | High | Novice | 2 participations (W1–W2) |

| B2 | High | Usual suspect | 4 participations (W1–W2–W3–W4) | |

| B3 | High | Usual suspect | 1 participation (W1) | |

| B4 | High | Usual suspect | 3 participations (W1–W2–W3) | |

| B5 | High | Insider | 3 participations (W2–W3–W4) | |

| City C | C1 | High to very high | Usual suspect | 2 participations (W2–W3) |

| C2 | High | Usual suspect | 1 participation (W2) | |

| C3 | Low | Usual suspect | 1 participation (W3) | |

| City D | D1 | High | Novice | 3 participations (W2–W3) |

| D2 | Very high | Insider | 4 participations (W1–W2–W3) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schelings, C.; Elsen, C. Assessing Participation: Toward Long-Term Experiences, Trajectories and Maturity. Architecture 2022, 2, 518-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2030029

Schelings C, Elsen C. Assessing Participation: Toward Long-Term Experiences, Trajectories and Maturity. Architecture. 2022; 2(3):518-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2030029

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchelings, Clémentine, and Catherine Elsen. 2022. "Assessing Participation: Toward Long-Term Experiences, Trajectories and Maturity" Architecture 2, no. 3: 518-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2030029

APA StyleSchelings, C., & Elsen, C. (2022). Assessing Participation: Toward Long-Term Experiences, Trajectories and Maturity. Architecture, 2(3), 518-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2030029