3. Readiness

It would have been essential to the survival of early humans to be able to predict weather patterns and where and when particular plants and animals were likely to appear. Even after people had settled to cultivate the land, there would have been few more reassuring sights than those of ample supplies of food, water, and fuel in the immediate vicinity. While we can readily purchase these items today, many of us still derive pleasure from contemplating our own supplies of essential resources, and in particular the sense of readiness for the future that this seems to elicit.

The long-term survival of our planet is even more critical than our own, of course. Making sustainable resources and/or practices visible, can be a powerful means by which built environments evoke can positive feelings about the future. One of the most common shortcomings of many LEED-certified buildings, for example, is that they fail to make their admirable sustainable strategies explicit. The book

Naturally Animated Architecture (2018) attempts to remedy this missed opportunity by demonstrating how a range of passive environmental control techniques—from shading to natural ventilation and solar heating—can be brought to more immediate public attention, effectively turning the buildings where we live and work into active teachers of sustainable practices [

4]. In addition to encouraging the wider use of these simple but underused techniques, such visibility can also evoke a more general positive sense that we are taking care of our long-term future.

Built environments can also be designed to evoke a more immediate sense of readiness for the future, in the form of the display of important material resources or visible signs of preparation for weather events that are beyond our control (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

5. Mental Exploration

While our preferences for certain kinds of natural environments have their origins in what were once survival advantages, geographer Jay Appleton emphasizes that this “does not mean that there is a direct, utilitarian relationship between those landscapes which afford us satisfaction and those which afford us safety” [

7]. Our landscape preferences today, then, would seem to be based more on the promise of potential enjoyment than on practical use.

The terms vista and prospect, for example, both imply an extended view, but the latter also carries with it an implication that there is something worth looking

at, some kind of objective

1. As Appleton confirms, “locomotion, either in achievement or in imagination, is an essential ingredient of participation in the experience of landscape”, but any large, open space can evoke a sense of potential movement. Appleton argues that we tend to prefer more complex scenes, particularly those that seem to offer the promise of adventure and achievement, often in the form of partially obscured paths to distant visible objectives [

7] (

Figure 4).

Henry Plummer suggests that, similarly, in built environments, “where hidden depths of architectural space allow us to probe and reveal their secrets, we become active seekers, rather than mere occupants or users of space. There is a sense of unknown country ahead, in which the adventurous spirit can work and from which it may continue forward” [

8]. This propensity to want to mentally explore the space ahead of us was exploited in Gordon Cullen’s famous sketches of urban environments, in which the observer is repeatedly beckoned onwards by the partial revelation of objects and spaces. Complex interior environments can generate a similar sense of curiosity and seem to invite us to imagine exploring the space in front of us, without actually moving (

Figure 5) [

9].

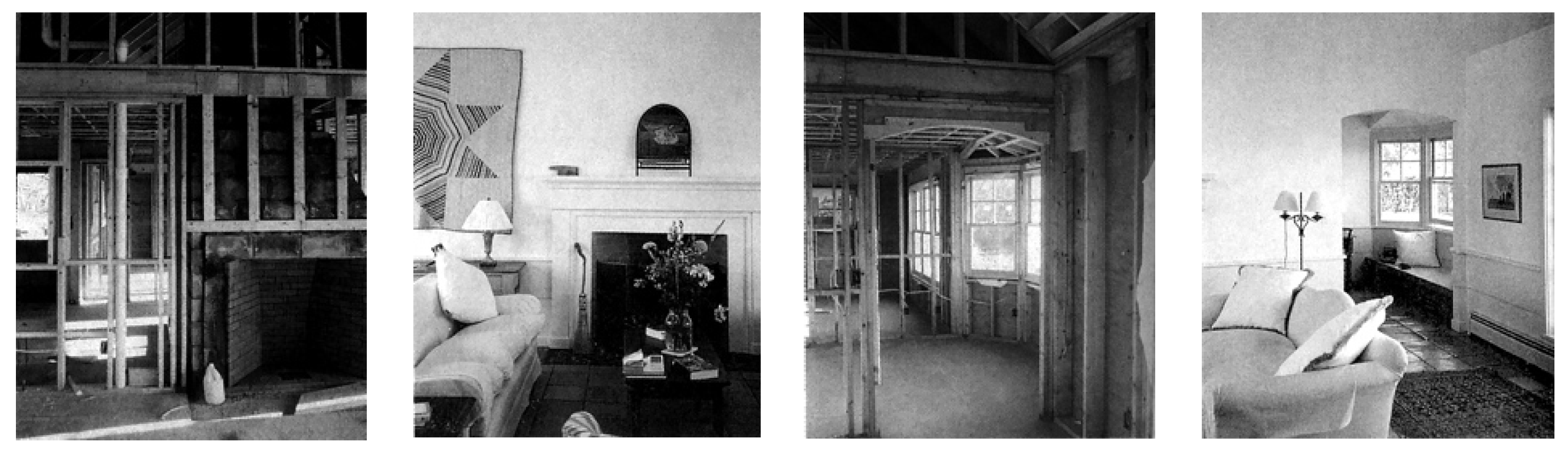

Our apparent preference for environments that offer spatially deep, complex views may explain why partially open rooms seem much more interesting than fully enclosed ones. When revisiting finished timber buildings that were previously seen in their framing stage, for example, I often experience a sense of disappointment over the many visual connections that have disappeared in the process of sheathing the walls. In the framed state, there seems to be almost unlimited potential for mental exploration, but with each sheet of plasterboard added these possibilities gradually disappear. The effect can be seen in a set of before and after photographs taken by the designer/builder John Abrams. The one remaining prospect of another space, on the right, seems positively liberating compared to the fully enclosed room (

Figure 6).

6. Looking Forward to the Future

While the ability to anticipate events has been critical to our success as a species, less obvious is the fact that our feelings about the future are also essential to our mood [

10,

11]. Psychologist Andrew Macleod writes that “a failure to experience a positive spark of feeling in the here-and-now when contemplating the future” is fundamental to depression [

12]. Seligman and Baumeister go even further, suggesting that “faulty prospection sets up a vicious cycle. It produces depression, and that, in turn, potentiates poorer prospection” [

13]. The main character in Steven Peck’s novel

A Short Stay in Hell seems to encapsulate this aspect of the human condition when he declares that “in hope’s loss … is the greatest despair” [

14].

The word “prospect” originally meant a distant view. It was not until the sixteenth century that the term took on the additional meaning of an anticipated event [

15]. The contemporary psychological concept of “prospection”, then,—our capacity to imagine future scenarios—is firmly rooted in a spatial analogy [

16,

17,

18]. Since we now spend so much of our time indoors, any connection between visual prospects and mood could have important implications for building design [

19].

In order to test whether such a link existed, in 2020, psychologist Job Chen and I conducted a series of experiments based on drawings of external views from indoor spaces. Our primary hypothesis, that distant views would be positively associated with the future, was strongly supported. The ability to see what lies in front of us spatially does in fact seem to be linked to a sense of what lies ahead of us in time. Moderation analyses also revealed that the increased sense of connection to the future evoked by an external view can be explained by a rise in optimism [

20].

These results are consistent with Appleton’s belief that “the ability to see without being seen is conducive to the exploitation of environmental conditions favorable to biological survival and is therefore a source of pleasure” [

7]. Having a restricted view of what lies in front of them would have been disadvantageous to early humans, leaving them vulnerable to possible attack and likely to miss opportunities. Having a broad, unobstructed view of what lay ahead of them, on the other hand, would have offered advance knowledge of both threats and opportunities.

A distant view tells us what is “coming”. That might be either something that is actually approaching us or what we would encounter were we to move forward ourselves. Both of these scenarios involve anticipated events based on imagined movement through space. Commanding such a view would have evoked a sense of agency and positive feelings about what lay ahead, in time as well as in space. The absence of such a prospect, then, may reduce those feelings. This could have important ramifications for the design of indoor environments, and in particular for those who are either unable to go outside or are prone to depression. The housebound and the hospitalized immediately come to mind, but hundreds of millions of people who are simply obliged to work indoors may also be impacted.

This finding could also modify interpretations of Roger Ulrich’s influential experiment comparing the recovery of hospital patients with a natural or built view [

21]. The built view was of a brick wall roughly forty feet away from the patient’s window, while the natural view was significantly deeper, actually

through a stand of trees (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). The presence of nature may not have been the only factor that played a role in the faster recovery rates of those looking through the trees, then. The brick wall presented patients with nowhere to go mentally, while the mind was free to wander through the trees to the wider world beyond.

The terms hope and optimism are often used almost interchangeably to indicate positive feelings about the future, but Arthur Brooks argues that hope “focuses more directly on the personal attainment of specific goals, whereas optimism focuses more broadly on the expected quality of future outcomes in general” [

22]. In other words, he suggests that optimism tends to be general and passive, while hope seems to be more specific and active [

23,

24]

2. Built environments seem capable of evoking both: the hope of using a resource, for example, and a more general sense of optimism stemming from either readiness or an engaging view.

7. The Pleasure of Options

The process of designing itself is, of course, inherently anticipatory. In this context, Stewart Brand has argued that rather than a single fixed building program, an approach based on a range of possible future scenarios is likely to mean that buildings remain in existence longer. Along similar lines, Kevin Lynch suggested that in order to prolong the life of buildings, “we may spatially separate elements likely to change from those unlikely to change” [

25]. The notion of varying rates of change is a central theme of Brand’s book

How Buildings Learn, in which he points out that while “structure persists and dominates”, “skin is mutable”, and “interiors change radically” [

26]. This idea was summed up in a layered diagram depicting the differing lifecycles of building components (

Figure 9).

For Brand, the longevity of buildings is “often determined by how well they can absorb new services technology” [

26]. He argued that the relative ease of replacing shorter-lived parts was often critical to extending the life of a building. As Lynch previously pointed out, “the effectiveness of this device depends on our ability to distinguish the changeable element from the stable one”. The idea of designing changeable shorter-lived elements within a much longer-lived structure was first proposed by Le Corbusier in the original “megastructure” project, the unbuilt 1933 Plan Obus, and subsequently in his explanations of the future of mass housing, but it never became a built reality in his work (

Figure 10).

Several of the projects built by the Metabolists in Japan similarly projected the image of replaceability without the means of actually achieving it in practice (

Figure 11). The same was generally true of the promise of future growth in many Metabolist projects, although, more than four decades after its original construction, the Yamanashi Press and Broadcasting Center by Kenzo Tange, often regarded as the godfather of the Metabolost group, was in fact successfully extended in 2016. There are several established principles in designing buildings for future extension, including locating services and circulation on external walls. What is often missing, however, are the visual cues that would help people to anticipate this future extension. One means of achieving this is to frame space in order to imply its future infilling. Again, this was first suggested by Le Corbusier in the Plan Obus. Unlike replaceability, however, this strategy has been successfully realized in practice, notably in the award-winning “Half Houses” designed by Elemental. Here, the sense of possibility and agency evoked by the unfilled spaces was palpable, and most were soon completed by their owners in a wide variety of ways that softened the uniformity of the original project (

Figure 12).

Preparation for many predictable life changes can also be signaled as a means of evoking confidence in the present. A daily reminder that elderly homeowners will not have to leave their long-term home when they can no longer manage the stairs, for example, could be a huge source of comfort to many (

Figure 13).

Replaceability, extendibility and changeability are all different manifestations of readiness. A possibility that all buildings are legally required to be prepared for, of course, is an emergency, but even visible readiness for routine maintenance can be a means of reassuring occupants (

Figure 14).

8. Implications

Future events can be divided into two general categories: those that are beyond our control and need to be prepared for, and those we would simply prefer to happen. Designed appropriately, built environments can accommodate both kinds of events with different benefits for their occupants. The sight of desirable resources, for example, tends to elicit hope of their eventual use. Signs of readiness, including for the long-term future of the planet, as well as engaging views, on the other hand, seem to evoke a more general sense of optimism. Each of these built means of connecting ourselves to a positive future can, it seems, help us to feel more content in the here and now.