Abstract

This paper aims at documenting and reconstructing the linguistic processes generating and substantiating the use of number systems, numbers in general, elementary arithmetic, and the related concepts and notions among the Kula people from Alor Island, Southeastern Indonesia. The Kula is a Papuan population from the Alor–Pantar Archipelago (Timor area). The name of their language, Kula (or Kola), corresponds to the ethnonym. The language is, currently, endangered and not completely documented. At the level of linguistic features, numeral systems and the terms for numerals from Eastern Alor exhibit, to some extent, unique characteristics, if compared to other languages spoken in other sectors of the island. Therefore, the Kula numbering system is not only significant at the lexicological and lexicographic level, but also represents the essential role of cognitive strategies (e.g., the choice of the base for the numbering systems and the visual representation of counting with the aid of actual ‘objects’, like hands and fingers) in the coinage of numerical terms among the local speakers. Indeed, the development of numeral systems reflects the evolution of human language and the ability of humans to construct abstract numerical concepts. The way numerals are encoded and expressed in a language can impact the patterns according to which numerical notions are conceptualized and understood. Different numeral systems can indicate variations in cognitive processes involving notions of quantities and measurements. Therefore, the structure and characteristics of a numeral system may affect how numeral concepts are mentally represented and developed. This paper focuses on the number system of the Kula people and the lexical units used by the local speakers to indicate (and to explain) the numbers, with the related concepts, notions, and symbolism. The investigation delves into the degrees of abstraction of the Kula numeral system and tries to ascertain its origins and reconstruct it. Moreover, the article applies to the analysis a comparative approach, which takes into account several Papuan and Austronesian languages from Alor Island and Eastern Timor, with the dual aim of investigating, at a preliminary level, a possible common evolution and/or divergent naming processes in local numbering systems and their historical–linguistic and etymological origins.

1. Introduction

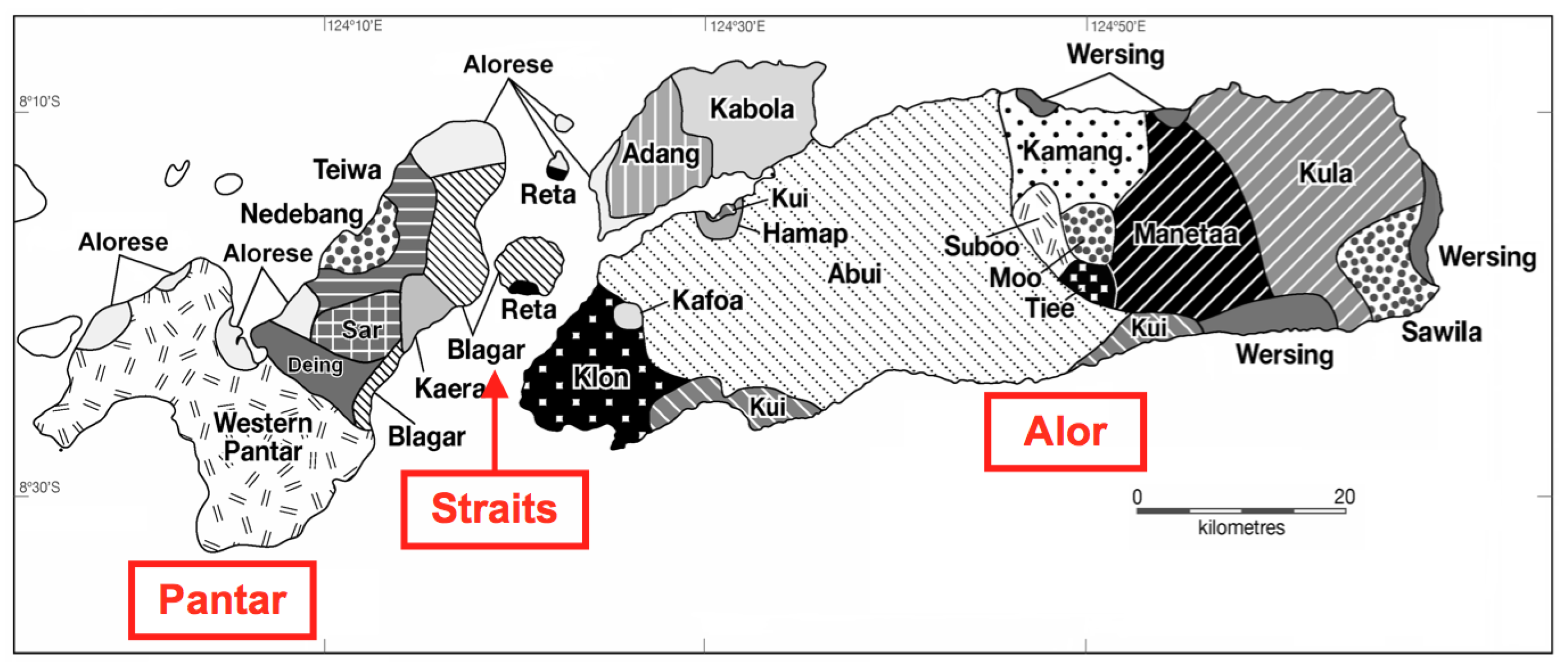

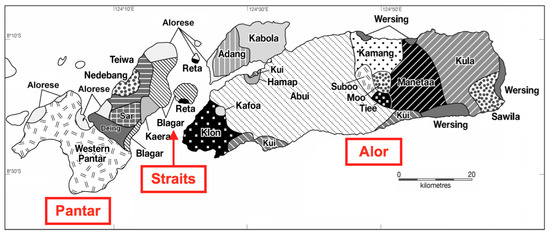

This paper aims to shed some light on the numeral system and numbering/counting practices of the Kula people from Alor Island, in Southeast Indonesia. Kula is the name of the language spoken by this population and is used also as its endonym. The language (which is called also Kola or Lantoka/Lamtoka or Tanglapui, ISO 639-3: tpg [1]; Glottolog: kula1280) belongs to the so-called Papuan family (the term ‘Papuan’ is, indeed, disputed and, generally, indicates groups of languages which might be not related or only loosely connected with each other [2]) and is included in the Alor–Pantar sub-family from the Alor–Pantar archipelago (an ethnic and linguistic map of Alor and Pantar is reproduced in Figure 1), in Timor’s area [3]. This insular territory is an ancient linguistic contact zone marking the border between Austronesian and Papuan languages in this part of Indonesia (Flores Island, located immediately West of the Alor–Pantar archipelago, shows a prevalently Austronesian linguistic environment, while, from Pantar, the languages attested are mostly Papuan). Kula, like all the languages from Alor, is represented by several dialects (Kula itself, Kulatela, Watena, Kula Watena, Larena, Iramang, Arumaka, and Sumang). This paper focuses on the ‘mainstream’ variant of the language (i.e., Kula). Kula is, currently, endangered and is spoken by about 5000 speakers from Eastern Alor in mountainous areas of the island and villages from the northern and southern coasts [4]. Considering the historical and geographical context, the Kula community had to endure a resettlement process that started in the 1960s [4]. Several villages were abandoned, and some areas traditionally belonging to the Kula community are now uninhabited. This was due to the movement of the population towards less isolated sectors of the island and to local strategic plans and policies. Several of the currently existing villages are, therefore, quite recent. In 2023, Kula is still spoken, in this new linguistic geography, by local speakers, but because it is not taught in schools, with a strong preference for Bahasa Indonesia as the dominant language among the younger generations, is being lost by its people. This dramatically highlights its status as an endangered language and draws attention to the imperative need for linguistic documentation aimed at the preservation of the cultural identity of the Kula people.

Figure 1.

Linguistic map of Alor and Pantar [5].

The analytic process we develop in this paper involves a ‘first-hand’ comparison among numeral systems in Kula and their equivalents in Sawila and Abui, two other Papuan languages from Alor. The parallel with Sawila is a stringent requirement for the assessment, since Kula and Sawila are two of the Easternmost languages on the island, and their lexicons and general features, while connected with each other, tend to diverge from the Western and Central languages of Alor. Indeed, Sawila and Kula belong to the Eastern Alor sub-group, while Abui belongs to the Nuclear Alor–Pantar sub-group. The comparison, therefore, is conducted among Kula, a language that is closely related to it (Sawila), and another language that is less closely related to it (Abui). Due to this, Sawila is an important indicator for a preliminary analysis of the diachronic development of Kula, and vice versa. At the general level, Sawila (called by the native speakers Manata) is another endangered and scarcely documented Papuan language from Eastern Alor, spoken, currently, by around 3000 speakers in several villages and characterized by a number of local dialects (Sawila itself, and Lona, Salimana, Lalamana, Sileba) [6]. A broader comparison with other Papuan languages from Alor, like Abui, can be valuable not only to highlight differences or analogies in the numeral systems within this branch of the Alor–Pantar sub-family, but also to assess the degree of divergence among those languages.

A secondary aim of the paper is a preliminary investigation of some basic cognitive aspects involved in the process of development of the Kula number system, with some comparisons with Abui and Sawila. This research, which is unfortunately limited in its scope because of space constraints, is nonetheless a contribution to the wider debate on the development of specialized terms in world languages and the notion of ‘numerical abstraction’ and aims to be an encouragement and starting point for further studies on Kula.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

Among the Alor–Pantar languages, Kula is not the most comprehensively studied at the moment, mainly due to the current distribution of the speakers over Alor and to some logistical difficulties in reaching the villages and finding consultants. Despite this, a good number of studies have been developed, especially on Alor languages in general, and we also have a reliable sketch grammar and relatively exhaustive lexical lists of Kula.

Williams [4] produced, indeed, an essential sketch grammar of the language, which can be useful also in the broader context of the Papuan languages spoken in Timor and in the Alor–Pantar archipelago [7,8,9]. The documentation effort is commendable, and the description of grammatical phenomena is very precise. Further development towards a complete reference grammar would be the next necessary step for the typological documentation of Kula to a fuller extent.

Other studies on the Alor–Pantar languages in general (especially on the Alor context) collect very significant details on Kula and even on its numeral system. Among them, it is possible to mention some very relevant chapters from Klamer [3], in particular Schapper and Klamer [10]. The same volume includes comprehensive descriptions of the languages spoken in Alor, often developed through a comparative approach. Specifically, Klamer [11] and Holton and Robinson [12] provide the readers with plenty of grammatical elements useful not only to understand the intrinsic structure and ‘working’ of the languages, but also their historical/genetic relationships.

Before these works, the Alor–Pantar languages were already described and categorized by Holton et al. [13] and Robinson and Holton [14]. Perono Cacciafoco and Cavallaro [15] tried to provide a preliminary framework to reconstruct etymologies from the Alor-Pantar lexicons based on an experimental comparative approach. However, their paper offers a quantitatively limited sample of analyzed lexical items, at the level of exemplification.

Kaiping [16] proposed a relatively innovative classification of the Alor–Pantar languages based on a systematic Bayesian phylogenetic approach, which adds up to the ongoing research inherent in the categorization and ‘branching’ of this Papuan sub-family.

What is still lacking, despite the admirable acribìa of these studies, is a comprehensive survey of the cognitive aspects involved in the creation of the lexical items of the documented languages, a complete assessment of their specialized vocabularies (e.g., numbers, phytonyms, medical terms, natural navigation, toponyms, etc.), and a comparative collection of oral traditions. Besides the documentation of raw data and their analysis, interviews and discussions with the speakers should be ideally aimed at shedding light on their perception of actions, notions, and concepts connected with their linguistic expressions and their lexicon in general, to capture the cognitive background of the original development of their languages.

Despite several reference grammars of Alor–Pantar languages are available [17,18,19], with some dictionaries [20,21] and collections of oral traditional stories (or papers documenting specific tales) from local contexts [22,23,24], a comprehensive survey of these essential linguistic and cultural elements from the archipelago is a stringent scientific need which has not been completely fulfilled yet.

Keeping the focus on numeral systems and counting in general, some valuable elements for comparison can come from more generic works dealing with the anthropology of ‘numbering’ and numbers and with the origins of arithmetic (when not of mathematics in itself). Books like Clawson [25], Rudman [26], and Heaton [27], especially in their first chapters, provide precise information and interesting ideas on several aspects of number creation and ancestral counting among prehistoric and native peoples, which can be used as an effective term of comparison for and with the Alor–Pantar context. They deal, among other aspects, with hypotheses on the origins of counting in prehistory (association of notions of numbers with pebbles, stone tools, or animals from a herd) and with body counting among native peoples mainly from Papua New Guinea and Australia. Examples of ancestral counting are also analyzed from Native American contexts (ranging from standard finger-counting to the names of canoes associated with body parts). Additionally, Everett [28] is a remarkable synthesis of the origins of counting in human cultures, with the related anthropological and cognitive implications. According to him, numbers are a cultural tool, which requires millennia to be developed and perfected. Everett claims that numbers are not innate, but intellectually created by humans, and represent one of the remarkable achievements of our species. His discovery derives from his work with Amazonian peoples. This book is a valuable source to be used as an interpretation tool for the reconstruction and analysis of the numeral systems considered in this paper.

In relation to cognitive perspectives, Lakoff and Núñez [29] highlight the arithmetical metaphor we ‘lived by’ as “The Arithmetic is Collection Activity”, which serves as the common ground of and for human numerical cognition. This metaphor, which implies the notions of ‘accumulation’ and ‘clustering’ (in the meaning of creating sets and sub-sets), is atavistically embodied in our daily activities, such as, for instance, when we collect and group items. Furthermore, it explains how we conceptualize numbers as entities put together out of constituted parts. Fayol and Seron [30] provide us with a contribution useful to understanding the universality and diversity of numerical representations across various languages. Their work reveals the shared cognitive process of naming quantities within culturally distinct contexts.

2.2. Methodology

As mentioned, in the context of the Alor–Pantar languages, years and years of work have produced very reliable lexical lists and grammars (as it results from the references of this paper). Oral traditions and specialized lexicons have also been partly documented (at least for some languages from the islands). Kula and Sawila have undergone this safeguard process, too, but a considerable amount of research is still necessary not only to augment the documentary collection, but also to double-check and validate the data already preserved from these languages.

For this study, field methodology has been applied, involving the collection of ‘first-hand’ elicited data (primarily oral, then transcribed) directly from native speakers, with the help of local consultants, and a verification process of already available linguistic elements, double-checked with our collaborators in situ and with their communities and through occasional discussions with some colleagues who are experts in the field. This allowed us to add to the existing (unpublished) corpora of the Kula and Sawila languages a considerable amount of newly discovered lexical items, both from the general vocabulary and from more specialized linguistic contexts, with very significant details inherent in Kula and Sawila societies and the history (and historical memory) of the related communities. These findings, which will be the subjects of future studies, involve local oral traditions, genealogies, and insights into social relationships among the native peoples. The challenge of dealing with multiple languages has been overcome through the application of the comparative method and by involving all our consultants in group sessions and interviews where the native speakers themselves were encouraged to think and discuss according to a comparative approach.

For this paper, only a fraction of the collected materials has been processed and analyzed, due to the specific topic of this work. However, the overall set of data recently documented will allow us, in the near future, to shed more light on the Kula and Sawila languages and cultures in general.

As a comprehensive, but not final, source, besides the studies mentioned in our literature review, we used the unpublished database of the Proto–Alor proto-language developed, over the years, at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, by František Kratochvíl, Gary Holton, Francesco Perono Cacciafoco, and others. This comparative lexicon is a work in progress, which needs completion at the etymological level and the level of validation, but is an indispensable source, because it provides scholars with reliable lexical lists from most of the Papuan languages of Alor, organized in a comparative fashion, with the aim of the reconstruction of their common proto-forms and roots.

The lexical and etymological approach has been substantiated by the essential contribution of local native speakers, which allowed us to confirm or disprove the accuracy of the transcriptions of some lexical items and their reconstructions (and perception among the speakers themselves) and to collect a consistent additional amount of data, which led us to some significant discoveries.

Indeed, in the last months, we worked closely with our Abui consultant from Alor (specifically from Takalelang), Mr. Benidiktus Delpada (born in Takalelang on 19 September 1984—a local linguist and researcher and Abui native speaker who cooperates with the Universitas Tribuana Kalabahi—Tribuana University of Kalabahi, Alor), whose help as a guide and translator (he is multilingual) has been instrumental in the interaction with and collection of data from our Kula and Sawila native speakers, respectively, Mr. Pak Otniel (born in Kaipera on 24 October 1965—a teacher of secondary school and Kula native speaker), and Mr. Pak Aris (born on 24 August 1957—a former teacher and Sawila native speaker). Pak Otniel lives in Kaipera, Desa Tanglapui, Kecamatan Alor–Timur, while Pak Aris lives in Kelurahan Nusa Kenari. Both native speakers are elders in their communities, and their knowledge of their respective languages goes beyond simple proficiency because they have a background in linguistics as teachers (moreover, they are to some extent bilingual). They also represent the ‘historical memory’ of their ethnic groups, and have provided us not only with their linguistic knowledge, but also with so far undocumented details about their oral traditions, cultural identity, legends, genealogies, and myths, in a continuous interexchange of information (and validation) with and within their communities.

Our interaction with them developed through a series of detailed interviews. The linguist in charge initially discussed general linguistic and anthropological features of Kula and Sawila languages and cultures with them. More specific topics were then included in the conversations, i.e., the local ways of dealing with arithmetic, mathematics, and counting. The sessions were recorded, and the relevant parts were transcribed. Common languages for mutual understanding were English, Indonesian, and Malay.

The constant presence of our (multilingual) Abui native speaker consultant provided us (through a continuous double-checking operation and direct discussion of original terms and forms) with the opportunity to apply a comparative approach not only between Kula and Sawila, but also taking into account Abui itself (and Papuna, which can be considered a local variety of Abui).

The procedure enabled us to highlight some natural inconsistencies in the collection of the pre-existing small corpus (from the Proto–Alor database) of mathematical and numerical terms in Kula and to update it, by providing a normalized and more logical explanation for the translation and etymological interpretation of the related forms. Our work in this context consisted mainly of standardization of the transcriptions of the terms, correction of some mistakes due to the misplacement of the terms themselves, and a systematic pairing operation of the forms with their glosses after a final double-check with our consultants. The unpublished database of the Proto–Alor proto-language we were using as a general reference has been, therefore, updated and enhanced accordingly.

The collected data were processed with a holistic approach involving consultation with specialists in the field (mentioned in the acknowledgments). Moreover, specific lexical items (not only numbers) were compared with possibly related terms, to ascertain if basic, but specialized lexical units (like numbers) can be part of the naming process of more complex words, like place names and anthroponyms. This analysis, which cannot be included in this paper due to space limits, may allow us to categorize lexical items in Kula and Sawila according to their internal morphology, through an assessment of families of words organized not by semantic fields, but by taking into account the internal composition of lexical elements.

Beyond the description and analysis of the Kula numbering system, our exploration of the Kula and Sawila languages and cultures is ongoing.

Speakers and consultants were timely compensated and recognized for their valuable contributions, and we developed our investigation according to the highest standards of ethics in language documentation. The speakers were provided with a comprehensive informed consent form to read and sign, and exhaustive information and details on our research, methodologies, ethical implications, data storage, and personal data treatment were given to them before the beginning of our study, while the works were in progress, and, in the end, when the collected data were already stored and being processed. Moreover, each speaker was duly compensated for the work developed, and we took the initiative of little donations to the local communities through our consultants for language preservation.

3. Results and Discussion

In the endeavor to compare languages and investigate their roots, no category of linguistic elements has undergone more meticulous examination than the set of lexemes universally present in virtually all human languages [31,32,33]. This specific lexicon comprises the basic numerical units, which serve as the foundation for quantitative expressions in linguistic discourse [34]. Moreover, exploring the essence of numbers involves the examination of how various species perceive quantities, a common ability that is likely proper not only of humans, as many creatures share at least a basic capacity to differentiate between greater and lesser quantities [34,35]. Recently, Núñez [36] highlighted the fact that the concept of ‘number’ is a product of cultural construction, influenced by, yet separate from, collective perceptions of quantity. Núñez’s argument is, therefore, a decisive point to comprehend the universality and cultural specificity of numeral expressions [35], with numbering intended not like an innate property of the human mind, but as a cultural phenomenon produced according to an evolutionary process. Previous studies have also documented the universal quantitative perception and culturally specific reckoning method in numeral systems of the Alor–Pantar language family. In this context, for instance, Abui and Sawila appear to follow a strategy that implies a mixture of quinary and decimal [37] numbering patterns (while the decimal system can foreshadow a notion of ‘universality’—which, ultimately, is not ‘universal’—, the mixed numbering procedures proper of these languages imply a development that is not uncommon, but which is, in this case, specifically local). The cardinal number system in Kula, indeed, consistently exhibits a combination of base-five (quinary) and base-ten (decimal) counting, which is recognizable within the language family. In the quinary numeral system, distinct numeral symbols exist for quantities up to five, and numerical aggregation commences thereafter, according to the basic way of counting on one hand [38]. As for the decimal system, the terms for all double-digit numerals in Kula reveal the addition and multiplication methods based on the number ‘ten’ as a possible evolutionary development of mathematical skills.

3.1. Ancestral Hand-Reckoning Thought: Cardinal Numbers from 1 to 9 (Quinary System)

In Alor–Pantar languages, according to the speakers, the terms for the numbers from ‘one’ to ‘five’ are typically mono-morphemic words [10] (p. 299), as shown in Table 1. Their mono-morphemic nature is not apparent and some terms are, technically, composed of two morphemes. We called them ‘mono-morphemic’ because they are perceived that way by the speakers, who do not de-compose them and treat them as ‘mono-morphemic’ words. This prevalent pattern implies the development of cardinal number abstraction skills (since the related terms have not a direct physical referent or, better, the physical referent itself is no longer perceived by the speakers when they count, nor apparent to them) among the Alor peoples, even though the cognitive process of naming, in this context, appears somewhat unclear.

Table 1.

Kula numbers from ‘one’ to ‘five’.

Indeed, as widely documented [39,40], subitizable quantities (up to about ‘three’ or ‘four’) are often associated with common environmental objects (e.g., ‘eyes’ or ‘arms’ for ‘two’) that embody the quantity in question, rather than the fingers. However, this does not seem to be the case with the local milieu we are analyzing and, therefore, this specific naming process remains relatively obscure.

Hands and feet represent the distinctive five-digit numerical canon and original matrix of human physiology in counting. Therefore, it is possible to hypothesize that the structure of numeral expression in Kula was, initially, organized through finger-counting. Indeed, during our fieldwork interviews, we have been able to validate this assumption with the help of our consultants. According to the Kula speaker, Pak Otniel, the word for the number ‘five’, in Kula, can be glossed as ‘ya-/yawa-’ and ‘-ten/-tena’ (the speakers cannot provide a clear reason for the existence of these allomorphs, not even after consultations with their communities), with the second morphemic part, ‘(-)tena’, being the word ‘hand’ in Kula. When the speakers complete the counting sequence to five with the hands, therefore, they reasonably connect the word for ‘hand’, ‘tena’, with the term for the number ‘five’, ‘yawa-tena’, and, hence, this is the resulting finger-counting method by Kula people. Speakers of languages are usually unaware of grammatical systems conditioning allomorphy in their languages. This issue can be solved through inductive linguistic (grammatical) analysis of the behavior of the forms in context. However, we discussed this with our speakers because one of them is a linguist and the other two have a background in Linguistics. We thought, therefore, that it would have been relevant to already provide the readers with this stage of the results.

Another interesting finding is the fact that the analysis of the naming process of the word for the number ‘five’ in Kula may further support the idea of ancestral finger-counting applied to the related numeral system. Indeed, in the context of finger-reckoning, the thumb on the left hand refers to the number ‘five’ in Kula, which is an aspect analogous to other languages within the Alor–Pantar family. In particular, according to our Abui, Sawila, and Kula consultants, ‘thumb’, in their languages, is ‘tataang heyaa’, ‘tatana ayabuko’, and ‘ateng (krik) g(h)ya’, respectively, and the literal meaning of these expressions is ‘our hand-its mother’, ‘our hand-its mother big’, and ‘our hand (finger) his/her mother’. Hence, the thumbs in their hands are cognitively and lexically related to the notion of ‘mother’, as a possible ‘generative member’ of a family nucleus (metaphorically represented by the fingers—in other words, the ‘thumb’ would figuratively foreshadow the idea of the ‘mother of the other fingers’, as well as the ‘hand’, inherently in the concept of ‘family’). ‘Thumb’ as ‘mother’ is a notion not unknown in the region [41] (in Kula, a standard term for ‘mother’ is also ‘ŋaya’, but ‘gya’ is the widespread form connected with counting). However, ‘mother’ is a word coined after the morphological form ‘*ya-’ (which is etymologically common to a set of words), in Abui and Sawila, while, in Kula, ‘five’ is ‘ya-/yawa-’. This might indicate a direct link between the two words and notions, but also a connection due to phonetic and phonological similarities and, in that case, the path of the diachronic development of the two lexical items, ‘mother’ and ‘five’, can be considered bi-directional (if the two terms are related, at the current stage of our knowledge, their development could have proceeded from one to another, but we cannot identify the original form). Bearing this phonological similarity in our minds, we might also speculate that the number ‘five’, ‘yawatena’ in Kula, has undergone a process of cognitive enculturation, which would have transformed the non-numerical body-part term, ‘thumb’, into the numeral ‘five’, due to Kula people’s specific tally methods proper of their cultural context [42]. According to dos Santos [42], one plausible strategy that could be employed for the creation of number terms involves specifically a process of enculturation. In this context, symbols representing numbers and the conceptualization of numerical values might have originated concurrently through re-semantification, wherein words originally non-numerical underwent a transformation in meaning. This would explain why ‘*ya-’ is so pervasive in this counting system. Additionally, according to Hurford’s [43] proposal, this change is developed through a gradual lexicalization. Therefore, the act of naming body parts in conjunction with body-part tallies eventually led to the development of numbers and related terminology. Since the possible morphological interpretation of the word for the number ‘five’ in Kula is ‘yawa(-)’ + ‘(-)tena’, which could be glossed as ‘mother’ + ‘hand’, the linguistic structures of ‘five’ and ‘thumb’, in Kula, look presumably related. Therefore, the term for ‘five’, rather than being connected directly with the notion of ‘hand’, would be linguistically associated, also at the morphemic level, with the concept of ‘thumb’, to form the numeral ‘five’ itself. Because of this, in the common perception of Kula people, we would have a direct link between the notion of ‘thumb’ and the numerical indication for ‘five’, which may imply the loss of an immediate awareness of the relationship and/or distinction between the two words semantically. However, the meaning and structure of the terms for the numbers from ‘one’ to ‘four’ are not easily understandable yet, and more comparative work and documentation are needed to ascertain the relationship between ‘thumb’ and ‘five’ in this numbering system. In this sense, extending the investigation to a larger group of speakers with linguistic competence would help in this task, and we hope these first findings and remarks can encourage the development of further studies on this issue.

Going ahead in counting, the numerals ‘six’, ‘seven’, ‘eight’, and ‘nine’ in Kula appear to belong to a base-five counting system too (namely, a quinary system). The linguistic structure of the numbers from ‘six’ to ‘nine’, indeed, is centered around the morphemic unit ‘yawating’, which equals to the Kula number ‘five’, ‘yawatena’ (‘(-)ting’ is, here, a variant of ‘(-)tena’, according to our linguistically trained speakers, and is perceived as such by all our consultants). Therefore, the structures of these numbers, as shown in Table 2, are as follows:

Table 2.

Kula numbers from ‘six’ to ‘nine’.

Any method of finger-counting in world cultures is believed to involve and imply a shared sensorimotor mechanism for the representation and manipulation of numerical data. This mechanism relies on the neurological interplay among regions of the brain responsible for perceiving quantity, recognizing finger positions, and orchestrating motor actions [44]. A similar conceptual model, established, among others, by Ifrah [45], suggests that humans, who possess ten fingers, unsurprisingly began counting with their hands and often developed base-ten numeral systems in different cultures and times over centuries and millennia.

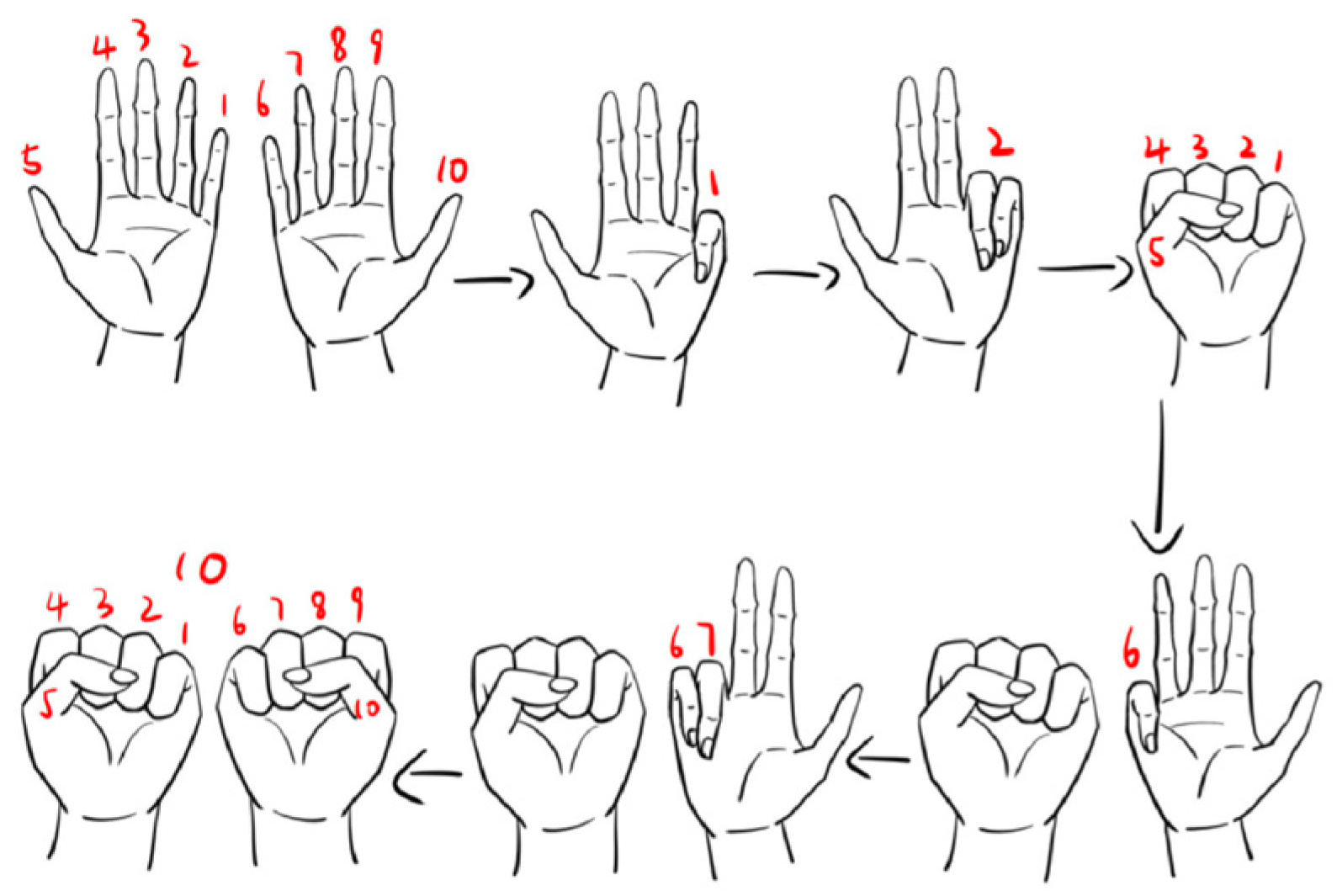

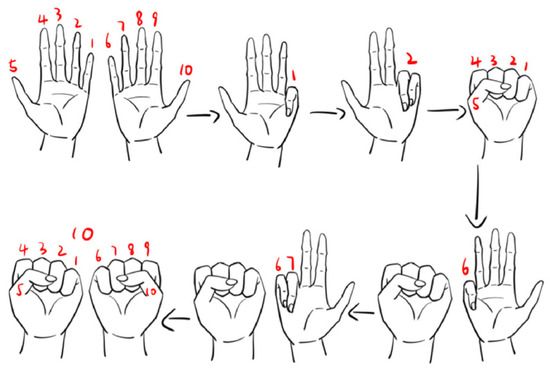

However, the linguistic structure of the numerals from ‘five’ to ‘nine’ in Kula reveals a base-five numbering system, which shows that the use of hands for finger-counting may not be determined only by neural factors, but might also be influenced by cultural elements [44], since the structure of the lexical items for numbers reveals a link to specific numbering strategies (ways to create, implement, and use numbering systems for counting), reflected also in the practice of hand-counting. Therefore, the base-five system appears in this local Papuan context to be closely linked to the culturally specific way of finger-counting methods employed by people from Alor. As for the natural act of representing ultimately abstract numerical notions through physical features, as shown in Figure 2, Kula people start counting from the little finger on the left hand and, then, move to the ring finger, middle finger, index finger, and, finally, the thumb. Once the tally on one hand is completed, they start from the number ‘six’ with the little finger again, but on the right hand, and, then, they repeat the same procedure. When the ten fingers are all bent, the series of numbers from ‘one’ to ‘ten’ ends (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The process of finger-counting among Alor peoples.

Hands and fingers are, generally, natural material devices in counting for native speakers. This follows a pattern common to many native contexts [25] and may date back to the origins of number systems and arithmetic, when not only hands and fingers but also tools and domesticated animals could have represented cognitive and material life ‘triggers’ for the development of counting procedures and skills [24,26]. These plausible natural elements, at the same time ‘inspiration’ and technical reasons for ancestral numbering systems, might have been configured, over time, as physical representations of new additional numbers (needed for greater quantities). For example, the ideal image of the two hands together and their related names could have started to indicate the number ‘ten’ not as the completion of counting from ‘one’ to ‘ten’, but as the representation of ‘ten’ in itself, as an ‘abstract’ number/name for a number and the starting point of counting above ‘ten’ [25].

Moreover, in the range of numbers between ‘one’ and ‘ten’, the fingers of the hands typically become involved in representing the first non-subitizable quantities (i.e., ‘five’ and ‘ten’). Once the hands are involved, the possible ‘gap numbers’ (‘four’ and ‘six’ through ‘nine’) are then filled in with the fingers and tend to be named after them [46]. However, in our case, the speakers tend to a fully ‘linear’ strategy for finger-counting, from ‘one’ to ‘ten’, in a sequence that could possibly represent the evolution of a more ancient (sequential, indeed) counting practice.

Therefore, for those speakers, the act of counting automatically involves the transition from one hand to another and the completion of one hand’s count before commencing with the other. As mentioned above, the numeral system of Kula utilizes ‘mono-morphemic’ words (at least in the speakers’ perception) for the numbers from ‘one’ to ‘five’. For the numbers that follow, instead of introducing a new name for the terms from ‘six’ to ‘nine’, they add ‘units’ to ‘five’ and, therefore, ‘six’ becomes ‘five (plus) one’, ‘seven’ becomes ‘five (plus) two’, and so on, thereby extending the ten-finger counting sequence as a (dual) base-five system.

3.2. Developed Mathematical Thought: Cardinal Numbers above 10 (Decimal System)

The base-ten system in Kula is interpretable through the analysis of the terms for larger numerals starting from ‘eleven’ (as shown in Table 3). This set shows to have regularized forms and, at the same time, exhibits (to some extent) ‘irregular’ terms, such as ‘resin’ (the ‘regular’ lexical item ‘wal’ is, generally, used by most of the ethnic groups in Alor, with the exception of those from the Eastern territories of the island, i.e., Kula and Sawila), which might be interpreted as potential borrowed words (due to language contact) from Timor–Alor Papuan and Austronesian languages.

For example, in all the following forms, the element ‘resing’ has been tentatively glossed, by the speakers, as ‘[to] gather’—we translated it as ‘plus’, in Table 3, to reproduce more directly the arithmetic operation of the numbers’ composition. Grammatically, ‘resing’ configures as a verb, according to all the data we collected. However, in current everyday conversation among the locals, the term is no longer used and is only involved in the composition of forms and expressions indicating quantities. Keeping this in mind, we have:

Table 3.

The Kula numbers ‘eleven’, ‘twelve’, ‘twenty-one’, and ‘twenty-three’.

Table 3.

The Kula numbers ‘eleven’, ‘twelve’, ‘twenty-one’, and ‘twenty-three’.

| Kula | ||

|---|---|---|

| adayok resing sona | ten (plus) one | eleven |

| adayok resing yok | ten (plus) two | twelve |

| adayok miyok resing sona | ten (times) two (plus) one | twenty-one |

| adayok miyok resing tu | ten (times) two (plus) three | twenty-three |

In this context, it is interesting to note that, in Kula, a phonological similarity exists between the numbers ‘two’ and ‘ten’. In particular, ‘two’ is ‘yok’, while ‘ten’ is ‘adayok’. This would make us think of a development of ‘adayok’ through compounding, which, morphologically, would be quite reasonable. However, ‘ada’ is not ‘eight’ in Kula (indeed, ‘eight’ is ‘yawatena tu’~‘yawating tu’); therefore, the common process of addition and/or multiplication cannot be considered here (‘yawatena tu’ stands for ‘five three’, but is the abstract term that the speakers provide when asked to pronounce the word out of context. In everyday conversation, they use ‘yawating tu’). Moreover, this surmise of the (possible) addition is not consistent with the naming process of the numbers from ‘six’ to ‘nine’, which implies a transparent cognitive pattern of finger-counting. This pattern is linearly sequential, but could have developed from subitizable numbers named after common environmental objects. In this case, as mentioned, the hands would have been used to express ‘five’ and ‘ten’, and the gap numbers would have been filled in on the fingers. Currently, as specified above, nonetheless, the speakers count in sequence, from ‘one’ to ‘ten’, using the numerical terms developed according to the naming process we are describing. Among the communities from Alor, the use and reason of the numeral systems are tightly related to actual natural and concrete elements, like crops or valuable goods to pay a bride price. Therefore, an intricate additive expression like ‘eight and two is ten’ might be linguistically incompatible with the local cultural customs [47] (p. 257), which would imply simpler analytical processes. Such arithmetic is also highly dependent on the explication of relations among numbers, something that typically involves the use of manipulable forms, like pebbles or tokens [26].

To better understand this apparent paradox, it is appropriate to apply a selective comparative approach to the analysis of the numeral ‘ten’ in Kula. In particular, in the neighboring language Sawila, from Alor, which shares many cognates with Kula, the term for the number ‘ten’ is ‘adaaku’. This form shows a clear similarity with the corresponding Kula number. If we hypothesize that the Kula form has been produced based on the Sawila numeral, we may think that the apparent Kula compound is not a proper compound in itself, derived from a process of addition, but a sort of reproduction of the original form. In this case, the second part of the compound, ‘(-)yok’, would not be, at the semantic level, the proper numeral ‘two’, but just an effectively sounding morphemic unit suitable to be involved in the composition of a numeral (because it is a numeral in itself, independently of its direct meaning), on the model of the Sawila form. This observation, of course, works only if we think that some numerals in Kula derive, by ‘mimesis’, from their equivalents from Sawila. In this case, the inherent linguistic phenomenon in Kula would be a sort of reanalysis with interesting cognitive implications. Actually, such theoretical postulation needs proof and, after several interviews with our Kula speaker, Pak Otniel, and his subsequent investigation among the community (he thoroughly discussed the issue with a considerable number of Kula people and summarized the related findings) about this interpretation, we have been able to adjust the initial assumption. When asked: “Do you think ‘adayok’ could still be glossed as a compound, and can you make any connection with any expression in Kula about ‘adayok’?”, Pak Otniel answered: “The ending ‘yok’ could stand for the number ‘two’, ‘yok’, and, sometimes, we tell ‘ada yok!’, which means ‘come together with two!’ or indicates something which appears together twice (textual: “comes/brings together with two”)”. According to the data we collected, ‘ada’ is configured as a verb, which can be glossed approximately as ‘put together/bring together’, and is normally used in everyday conversation among the communities. At the level of counting, it is possible, therefore, that “comes together with two” may refer to ‘come with two (hands) or take along two hands’, after the speakers complete their counting with two hands, and thus it is logical to consider the fact that the conceptual configuration of the number ‘ten’ still aligns perfectly with the finger-counting cognition and convention of these native people. This summing-up of ten fingers in counting tradition, as highlighted by Conant [34], would generate a ‘part–whole’ cognitive process, while producing a new numeral unit, ‘two-hands’ (which would eventually become a new numeral in itself, in and for the formation of numerals above ‘ten’), opening a wider scale for reckoning. To complete the range of theoretical options, it is possible to postulate that Kula borrowed ‘ada’, at some point in time, with a specific (presumably lost) meaning, and then derived the form ‘adayok’ from this process. The form ‘ada’ is not attested in Abui, Sawila, and other languages from Alor (therefore, it could be a borrowed word from an external source). This, however, cannot be proven, and not even diffusely discussed, at the current stage of the research. A phonological similarity can be highlighted between ‘ada’ in Kula and ‘ada’ in Indonesian, but the semantic values and the differences in the use of the terms make this parallel unlikely.

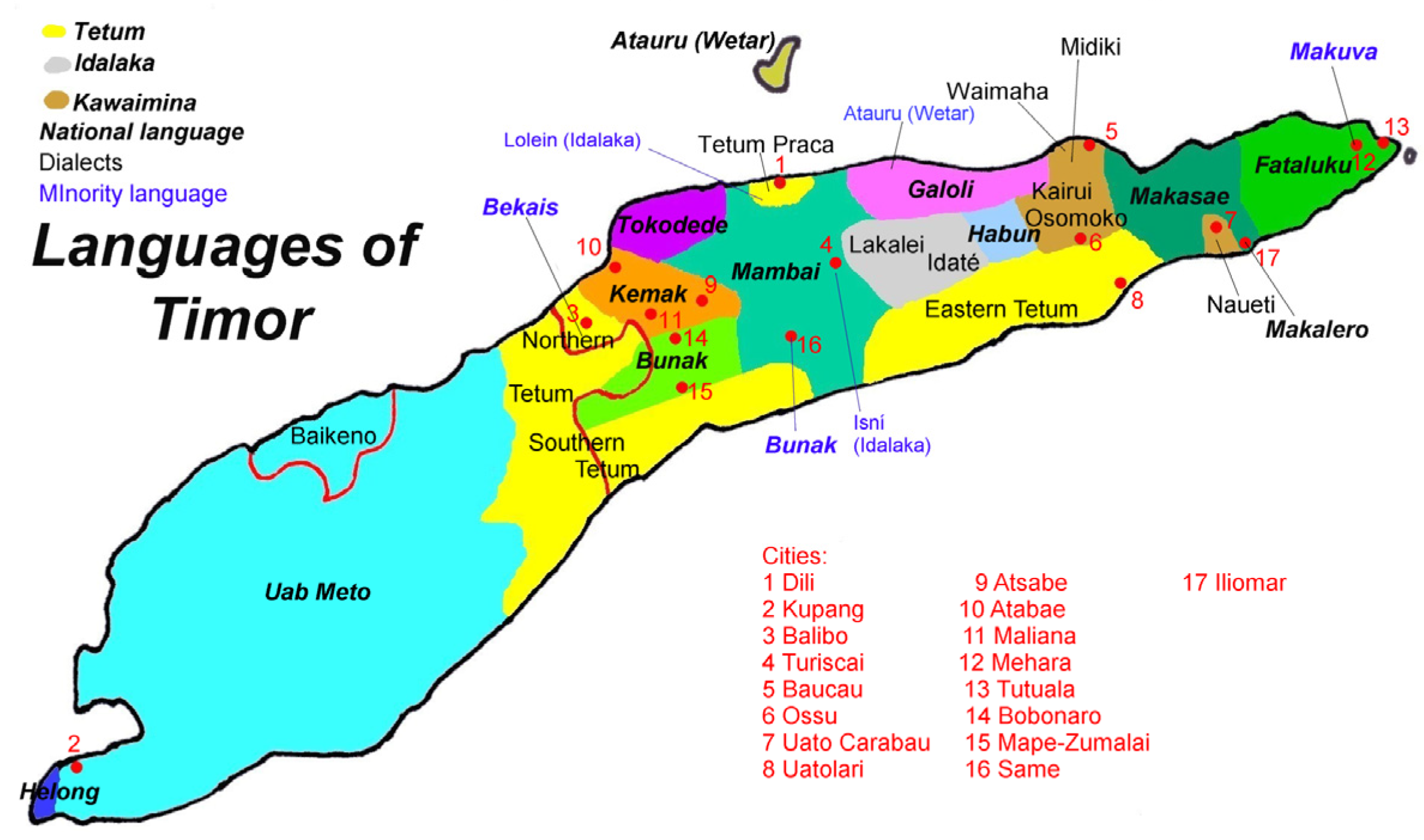

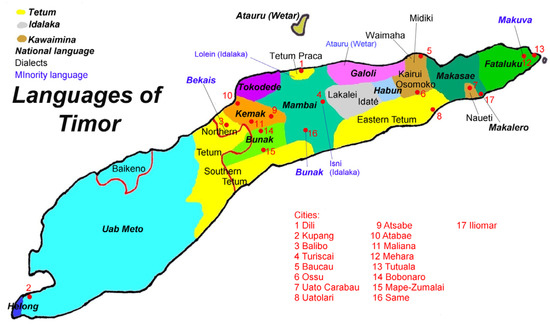

Alor and Pantar, as mentioned, are two islands located at the linguistic and cultural border with Austronesian peoples and areas, in an ideal path going (at least) from Flores to Timor (and, to some extent, in the opposite direction). Figure 3 provides the readers with an ethnic and linguistic map of Timor. The Alor–Pantar languages do not belong to the Austronesian language family. However, phenomena of language contact and cultural interexchange between them and the neighboring Austronesian contexts have developed since very remote times and have deeply affected the linguistic and ethnic environment of the archipelago.

Figure 3.

Elaboration of a linguistic map of Timor [48].

For this reason, a comparative approach focused on the Austronesian (~Malayo-Polynesian) lexicon is always necessary in studies like ours and we have applied it, for instance, while trying to ascertain the origins of the morpheme ‘ada-’, considering the potential links and contacts between Eastern Alor and neighboring Austronesian areas [49] (pp. 57–100). Indeed, the reconstructed proto-Austronesian form ‘*adaS’ and the composed (proto-)form ‘*um-adaS’, which indicate the actions of ‘taking, taking along, and bringing’ [50], might be phonetically, phonologically, morphologically, and semantically compatible with ‘ada-’ in Kula (Austronesian forms developed an additional sound at the end of most terms derived from this root. However, the original etymological stem seems to be ‘*ada-‘, or the consonantal sound could have been lost in the process of borrowing). This interesting similarity, which would imply a phenomenon of contact, nonetheless, cannot be found in the languages from Central and Western Alor (as mentioned, Kula and Sawila represent, in a way, the Easternmost linguistic development of the Alor-Pantar family). For instance, the word for the number ‘ten’ in Abui is ‘karnuku’, and the morpheme ‘ada-’ does not belong, in general, to Central and Western Alor vocabularies.

Additionally, another ‘anomalous’ expression from the Kula numeral system, when compared to languages from Central and Western Alor, may suggest a possible phenomenon of language contact between Eastern Alor and Timor Leste. The linguistic format of the above-listed examples from Table 2 is developed with a transparent and consistent additive counting method, wherein a marker like ‘resing’ occupies a position between the digit(s) for ten(s) and the digit(s) for a single unit(s) as an indicator of addition. The concept of addition, which is attested in words representing numerals beyond the number ‘ten’, indeed, is a common feature among Alor languages. However, the linguistic form conveying the notion of ‘aggregation’ differs etymologically between Central–Western (e.g., in Abui, the word for ‘eleven’ is ‘karnuku wal nuku’, with ‘wal’ meaning ‘add, gather’) and Eastern Alor (as exemplified by the terms with Kula ‘resing’ and Sawila ‘resin’, each one corresponding in meaning and function to the numerals above ‘ten’ in Abui).

This lexical discrepancy prompted us to thoroughly analyze this pattern within the so-called ‘Timor–Alor–Pantar’ (broad) language family, in order to trace the origins of the term ‘resing’ in Kula, by comparing the relevant lexical item(s) with possible cognates from outside Alor. Indeed, a similar form, ‘resing/resin’, is also attested in numerals from Tetum (Austronesian language) and Makasae (Papuan language) from Timor-Leste. To be more specific, Correia [51] highlights the presence of the numerical term ‘resi’ in Makasae. This marker is used after the number ‘ten’ and carries the meaning of ‘more than, plus, the rest’, findable also (with little variation) in Kula and Sawila. Possibly, it originated from the Tetum language, specifically from an attested form of ‘resin’. Consequently, it is plausible to think that Kula borrowed ‘resing’ from that linguistic context. It is even possible that Kula took the term directly from Tetum, as opposed to a previously suggested source hypothetically recognized in Tokedede, another Austronesian language from East Timor [10], compared to Kula in order to resolve this terminological puzzle pertaining to numerals beyond ‘ten’. Independently of that, the numerals in Kula undeniably exhibit a strong correlation with languages from Eastern Timor, for instance, Tokodede and Mambae (another Austronesian language), which share with it the format of their base-five cardinal number systems [10]. The dynamics of this borrowing process, despite being relatively evident, need to be clarified through consistent documentation, in order to establish the actual relations and connections among languages and also to better define the direction of the linguistic and cultural contacts. Even the direct etymology of ‘resi’/‘resing’/‘resin’ is still unclear and requires further investigation.

A more ‘regular’ set of numerals in Kula is documented starting from the number ‘twenty’ (as shown in Table 4). ‘Twenty’, in this language, is ‘adayok miyok’, with ‘*mi(-)’ indicating iteration (a sort of ‘multiplication by juxtaposition’) and, in particular, the notion of ‘times’ [10,37].

Table 4.

The Kula numerals for the tens from ‘twenty’ to ‘ninety’.

The formation of the number ‘twenty’ and the following tens is centered around the term for ‘ten’, showing the progression of a decimal counting system with the prefix ‘mi-’ added to the single unit(s) digit(s), which is a unique element from the Eastern Alor numbering sets. We have to think, therefore, that, in this case, ‘mi-’ has the value of a marker indicating multiplication (per ten), or the notion of ‘ten/tenth’ in general. This, probably, implies a later development of these numerals, when Kula people started to need bigger quantitative indicators which required a more complex and intellectually advanced method of composition of numerical terms. This is clearly a preliminary finding, which would require final confirmation from more research on Kula morphology and grammar. However, the reconstruction looks reasonable and in line with the counting strategies among these people.

At the level of clarification, it is appropriate to point out that the basic numbering systems (from ‘one’ to ‘ten’) in Kula, Sawila, and Abui and, possibly, also the sets of numbers above ‘ten’ are considered ‘ancient’ by the local speakers, and they are connected, in their beliefs and explanations, with ancestral counting. It is impossible to exclude a priori (because we are developing our analysis in undocumented contexts) that the ‘invention’ (or ‘introduction’) of these numbering systems is relatively recent. We believe in any case that the common perception of the speakers of the origins of their terms for numbers and counting strategies is correct and that they reflect ancient stages of the development of the related languages and basic arithmetic.

4. Conclusions

To sum up, this article aimed to shed light (at the descriptive and comparative level) on the cardinal numeral system in Kula, a language spoken in Eastern Alor, and to highlight the underlying etymological and intellective processes related to local mathematical concepts in the specific insular area and more general contexts.

However, the focus of this paper, which reflects the current stage of the related research on Alor languages, is necessarily limited to the cardinality of numbers, without a comprehensive investigation of ordinal and nominal aspects—this will require a larger study (already in our plans and for which this article is the ‘forerunner’), which cannot be performed here because of space limits.

Our study provides the readers with a preliminary description of counting in Kula, with important comparative elements from Abui and Sawila. Moreover, we have been able to highlight the undeniable linguistic and cultural connection of Kula with the East Timor context and the osmotic relationship between Papuan and Austronesian languages in the ideal route going from Flores to Timor.

Basically, the goal of our paper is to be a starting point not only for a more comprehensive study of numbering systems in the Alor–Pantar archipelago, but also an encouragement to scholars in the field to continue to exhaustively investigate the connections, at the cultural and linguistic level, between Timor and Alor.

Moreover, the linguistic position of Kula and Sawila among the Alor–Pantar languages requires specific attention, being these languages, especially at the lexical level, quite unique, in the archipelago. A clear and complete understanding of their position within the Alor–Pantar family and of their origins (with the complementary aim to better define remote population movements and settlement dynamics in the local context) should be the outcome of a research that cannot be further delayed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W. and F.P.C.; methodology, F.P.C. and S.W.; formal analysis, S.W. and F.P.C.; investigation, S.W.; resources, F.P.C.; data curation, S.W.; image curation, S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W. and F.P.C.; writing—review and editing, F.P.C. and S.W.; funding acquisition, F.P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by and developed in the context of the research grant “Place Names and Cultural Identity: Toponyms and Their Diachronic Evolution among the Kula People from Alor Island”—Research Development Fund (RDF) Grant, Grant Number: RDF-23-01-014 (Principal Investigator: Francesco Perono Cacciafoco), funded by the School of Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS), Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU), Suzhou (Jiangsu), China, 2024–2025 (funding number: RDF-23-01-014).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University Research Ethics Review Panel of Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (protocol code: ER-LRR-11000102420231202160001).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study (for in-person interviews, online interviews, data collection, personal data protection and publication, data management and publication in general, all ethical and technical aspects have been represented and listed in the informed consent forms).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. Data collected and used in this study are safely stored in physical data discs and in an online (private) data repository.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank very much our local consultants and native speakers from the Abui, Kula, and Sawila communities, in particular Benidiktus Delpada (known in his community as Benny), Otniel Mokoni (known in his community as Pak Otniel), and Aristarkus Malaikosa (known in his community as Pak Aris). Without their generous support, this paper would not have been possible. Their contributions go always beyond the ideal ‘borders’ of language documentation and are essential in safeguarding the cultural identity and the heritage of the Alor people. A huge ‘thank you’ goes also to the Abui, Kula, and Sawila communities in their entirety. We would like to also thank František Kratochvíl, from the Palacky University, in Olomouc, Czech Republic, for his valuable advice and support. Last, but not least, we would like to extend our gratitude to the anonymous reviewers of the paper, who, through their valuable comments and observations, have greatly contributed to the enhancement of the article, as well as to the editors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- tpg; International Organization for Standardization (ISO 639-3 Language Coding Agency) Code. SIL International: Dallas, TX, USA, 2007. Available online: https://iso639-3.sil.org/code/tpg (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- Palmer, B. (Ed.) The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area: A Comprehensive Guide; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klamer, M. (Ed.) The Alor-Pantar Languages: History and Typology; Language Science Press: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, N.J.K. The Papuan Languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar; Schapper, A., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 185–266. [Google Scholar]

- Schapper, A.; Huber, J. State-of-the-art in the documentation of the Papuan languages of Timor, Alor, Pantar, and Kisa: A bibliography. Wacana 2012, 14, 370–404. [Google Scholar]

- Kratochvíl, F.S. The Papuan Languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar; Schapper, A., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 358–438. [Google Scholar]

- Schapper, A. (Ed.) The Papuan Languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar; De Gruyter: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1–509. [Google Scholar]

- Schapper, A. (Ed.) The Papuan Languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar; De Gruyter: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 1–358. [Google Scholar]

- Schapper, A. (Ed.) The Papuan Languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar; De Gruyter: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 3, pp. 1–432. [Google Scholar]

- Schapper, A.; Klamer, M. Numeral systems in the Alor-Pantar languages. In The Alor-Pantar Languages: History and Typology; Klamer, M., Ed.; Language Science Press: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 277–328. [Google Scholar]

- Klamer, M. The Alor-Pantar languages: Linguistic context, history and typology. In The Alor-Pantar Languages: History and Typology; Klamer, M., Ed.; Language Science Press: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 5–53. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, G.; Robinson, L.C. The internal history of the Alor-Pantar language family. In The Alor-Pantar Languages: History and Typology; Klamer, M., Ed.; Language Science Press: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 55–97. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, G.; Klamer, M.; Kratochvíl, F.; Robinson, L.C.; Schapper, A. The Historical Relation of the Papuan Languages of Alor and Pantar. Ocean. Linguist. 2012, 51, 86–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.C.; Holton, G. Internal Classification of the Alor-Pantar Language Family Using Computational Methods Applied to the Lexicon. Lang. Dyn. Chang. 2012, 2, 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perono Cacciafoco, F.; Cavallaro, F.P. Roots from the Archipelago: Proto-Alor Etymologies in the Context of Alor Languages. Ann. Univ. Craiova Ser. Philol. Linguist. 2018, 40, 141–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiping, G.A. The Dialect Chain of the Timor-Alor-Pantar Language Family: A New Analysis Using Systematic Bayesian Phylogenetic. Lang. Dyn. Chang. 2022, 12, 274–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochvíl, F. A Grammar of Abui. Ph.D. Thesis, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, L. A Grammar of Klon: A Non-Austronesian Language of Alor, Indonesia; Pacific Linguistics: Canberra, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Klamer, M. A Grammar of Teiwa; Mouton: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kratochvíl, F.; Delpada, B. Kamus Pengantar Bahasa Abui; UBB-GMIT: Kupang, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, G.; Lamma Koly, M. Kamus Pengantar Bahasa Pantar Barat; UBB-GMIT: Kupang, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kratochvíl, F.; Delpada, B. Abui Stories from Takalelang; Universitas Leiden-GMIT: Kupang, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Perono Cacciafoco, F.; Cavallaro, F.P. The legend of Lamòling: Unwritten memories and diachronic toponymy through the lens of an Abui myth. Lingua 2017, 193, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perono Cacciafoco, F.; Cavallaro, F.P. Lamòling Bèaka: Immanence, rituals, and sacred objects in an unwritten legend in Alor. Religions 2018, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clawson, C.C. The Mathematical Traveler: Exploring the Grand History of Numbers; Perseus Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rudman, P.S. How Mathematics Happened; Prometheus Books: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, L. A Brief History of Mathematical Thought; Robinson: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, C. Numbers and The Making of Us: Counting and the Course of Human Cultures; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G.; Núñez, R.E. Where Mathematics Came From; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fayol, M.; Seron, X. About Numerical Representations: Insights from Neuropsychological, Experimental, and Developmental Studies. In Handbook of Mathematical Cognition; Campbell, J.I.D., Ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Acquaviva, P.; Daniel, M. Number in the World’s Languages: A Comparative Handbook; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, H. Numbers, Language, and the Human Mind; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hurford, J.R. The Linguistic Theory of Numerals; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Conant, L.L. The Number Concept: Its Origin and Development; Macmillan and Company: London, UK, 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Overman, K.A. Constructing a concept of number. J. Numer. Cogn. 2018, 4, 464–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, R.E. Is there really an evolved capacity for number? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratochvíl, F. Numbers in Abui and Sawila. In Number and Quantity in East Nusantara: Papers from 12-ICAL, ICAL-12, Bali, Indonesia, 5–6 July 2012; Klamer, M., Kratochvíl, F., Eds.; Asia-Pacific Linguistics: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dantzig, T.; Mazur, J. Number: The Language of Science; Pi Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Epps, P. Growing a numeral system: The historical development of numerals in an Amazonian language family. Diachronica 2006, 23, 259–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epps, P.; Bowern, C.; Hansen, C.A.; Hill, J.H.; Zentz, J. On numeral complexity in hunter-gathering languages. Linguist. Typology 2012, 16, 41–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikhenvald, A.Y. The Manambu Language of East Sepik, Papua New Guinea; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, C.F. Enculturation and the historical origins of number words and concepts. Synthese 2021, 199, 9257–9287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurford, J.R. Language and Number: The Emergence of a Cognitive System; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Overman, K.A. Finger Counting and Numerical Structure. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 723492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ifrah, G. The Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to the Invention of the Computer, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Overman, K.A. The Materiality of Numbers: Emergence and Elaboration from Prehistory to Present; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hallpike, C.R. The Foundations of Primitive Thoughts; The Chaucer Press: London, UK, 1979; pp. 236–257. [Google Scholar]

- Elaboration of a Linguistic Map of Timor by Fischer, J.P., Open-Access (CC BY-SA 3.0). Available online: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Timor_Sprache_en.png (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Klamer, M. Traces of pre-modern contacts between Timor-Alor-Pantar and Austronesian speakers. In Traces of Contact in the Lexicon; Klamer, M., Moro, F.R., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 4, pp. 57–100. [Google Scholar]

- Austronesian Comparative Dictionary. Available online: https://www.trussel2.com/ACD/introduction.htm (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Correia, A.J.G. Describing Makasae: A Trans-New Guinea Language of East Timor. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Western Sydney, Penrith, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).