Abstract

This article discusses collaborative ethnography as a meaningful source for spatial research, in particular, for participatory methodologies in urban planning and placemaking processes. It investigates the experiences with co-creation and co-research in different research projects to gain insight into the performance of collaborative ethnography as a technique to explore and enrich local knowledge. To better understand the possible causal relationships between the experience gained in the projects and the learnt lessons, we also identify recommendations for improving research methodologies to be applied in placemaking. This article concludes that collaborative ethnography is an effective tool for adding value to spatial co-research and co-creation processes. It opens opportunities for the co-production of space, ideas and knowledge, contributing at the same time to better informed decision-making. It also helps improve ideas and gather insights into the spatial needs of focus groups.

1. Introduction

Thinking about, promoting, planning, building and preserving a healthy and quality urban environment that meets the needs of citizens and society is one of the main priorities of urban development. From this perspective, public open spaces (parks, squares, playgrounds, streets, riverfronts, etc.) are a fundamental common good and a key to providing a healthy living environment [1]. As a physical space for social use, public open spaces, henceforth POS, also act as a place of communication, interaction, interaction and connection and is a common ground for cohesion and sharing, negotiation and contestation. POS define and structure, give character to the city, and create meaning for citizens, as they provide symbolic, memory and representation functions in urban life [2,3,4]. POS are defined by certain features (accessibility, leisure, engagement, etc.), each playing an essential role in improving the quality of the urban environment and social life and providing the space for mobility, contact with nature, social, cultural and physical activities, and a diversity of daily and occasional experiences. As a stage for social life, it is thus important that a POS is well maintained, inclusive and accessible [5]. The multidimensional nature of a POS entails a dynamic and dialectical interrelationship between the social and physical environment, which influences practices, representations and experiences. As places of collectiveness, approaching, planning, producing and managing POS require different kinds of knowledge and the involvement of several disciplines [2,3,4,5,6,7]. This collectiveness stresses the fact that a POS “speaks in the plural” and, as such, “conveys an ambiguity of meanings” [7] (p. 15). Hence, the features and performed activities bring the POS into the focus of different disciplines. This, in turn, highlights the importance of inter/multi/transdisciplinary perspectives to approach, study and intervene in POS, and the pertinent adoption of participatory, collaborative and co-creative approaches [8]. This brings us to the placemaking concept, place-related identity and the collective re-imagination and reinvention of spaces [9] towards reshaping them for mutual benefits [2,6,9]. Placemaking facilitates establishing innovative co-creation processes and use patterns, as it gives special consideration to the physical, cultural and social identities that characterize a place and sustain its continuous development [2,4,5,6,9,10]. Furthermore, the engagement of the community, understood here as groups of stakeholders with shared interests and strong connection to their environment, implies involving a concerned group interested in actively provoking changes [4,6,11]. It is therefore crucial to advance knowledge about how POS, as common goods, are developed, used, appropriated, experienced, perceived, imagined and represented. This calls, on the other hand, for a better understanding of people’s spatial needs, and ideas and proposals for developing more responsive spaces [2,4]. Encouraging cross-sector collaboration helps also to identify different ways to engage and get communities involved, also in managing and maintaining POS, thus paving the way to the sustainability and resilience of cities.

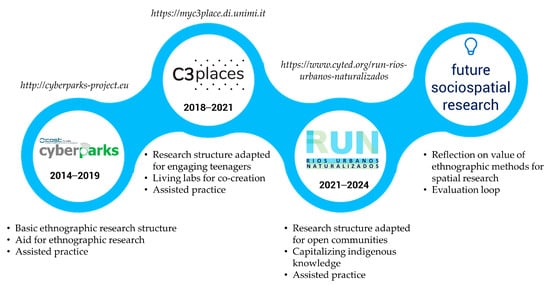

Backed by this multifaceted understanding of POS, also as places for performing urbanity and citizenship, this paper focuses on research ontologies and methodologies applied in different research projects that have advancing knowledge on co-creation of POS and meeting people’s needs at their core. Based on the learning acquired from the European projects CyberParks [12] and C3Places [13], and an Ibero-American project, Cyted RUN [14], this article aims to discuss the role of collaborative ethnography within the scope of participatory urban design and planning. The research in these projects, although varying in their aims and goals, hinge on four major common themes: co-creation of the public realm; engaging communities and stakeholders in urban places; generating a deeper understanding of the relationships between space (and environment), culture and society; and to underpin strategic, methodological and planning recommendations. Overall, a collaborative ethnography approach can be seen as an umbrella platform under which these research projects and their activities emerge and overlap. This highlights the role of collaborative and co-creative methodologies for research towards informing policies for more inclusive, responsive and sustainable POS [1,2,9,10]. To achieve this, research must embrace a wider concept and focus on ways to meaningfully engage people. Collaborative ethnography is used in this article to put field experiences into a wider perspective, to dialog together in the frame of these individual projects. It is used to articulate different techniques for collecting, analyzing and evaluating data (for example, visual and field observation, interviews, questionnaires, etc.). This enables us to create a repository about people and their sociospatial realities [2,8,9,11]. How such repositories were built in three projects (CyberParks, C3Places and Cyted RUN) along with their rationale are at the core of this article. Based on garnered lessons, we discuss the added value of collaborative ethnography for spatial research. To better understand the purpose of its use, a short description of the projects and their methodological approach are provided. Backed by the experiences gained with this process, we discuss the role of collaborative ethnography for participatory approaches, for placemaking and for informing urban design and planning policies.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to discuss the role of collaborative ethnography in placemaking, this article addresses the ontologies and the methodologies used in three different research projects. These projects, despite having different aims and goals and having been executed in different time frames, have establishing a people-centered approach at their core, with actions that engage local communities and tap into local knowledge. These three placemaking projects were selected because they follow a participatory research approach and are driven by advances in information and communication technology (ICT). The projects consider also the stakeholders’ contribution to more participatory dynamics in urban and planning.

The three projects were discussed following an established common framework, consisting of three stages. In the first, oriented on a qualitative content analysis basis, the projects’ outcomes were analyzed. However, to better understand how the results were achieved, a short description of each project is provided. From this stage, a set of dimensions and assumptions could be filtered. The second stage involved an analysis that relates these dimensions. It was performed in order to identify coherent structures, also considering the fact that each project yielded a variety of qualitatively different results. Armed with the “key lessons”, the third stage consisted of explaining these and looking at the mentioned dimensions in the literature.

3. Results

3.1. The Projects and Their Ethnographic Approaches

3.1.1. Project CyberParks—Fostering Knowledge about the Relationship between Information and Communication Technologies and Public Spaces Supported by Strategies to Improve Their Use and Attractiveness

The project CyberParks aimed to create a platform for knowledge exchange about the role of information and communication technology (ICT) in the production of POS and how it provokes changes in the social practices and appropriation of POS. This enabled us to analyze the relationship between production of a POS, sociospatial practices and the use of ICT devices for outdoor activities. Started in 2014, CyberParks pioneered in providing a better understanding of the relevance of these relationships for promoting sustainable and more socially inclusive urban development. Within the scope of CyberParks, a basic research structure was developed to serve as a guide to aid the design and conducting of ethnographic research. To this end, this structure (see Table 1) is based on the following two main dimensions of analysis: (1) intersections between ICT and POS, and the dynamics of social interaction; (2) intersections between ICT, planning and citizen participation. To develop the analysis framework and guidance for a collaborative ethnography and participative approach to studying POS, the project first systematized its objectives and identified the most relevant dimensions that reflect them. A small-scale exploratory study was carried out in the Jardim da Estrela and Parque da Quinta das Conchas, Lisbon (Figure 1). This fieldwork took place with project members in June 2014 during a project meeting in Lisbon. This exploratory study aimed at collecting foreigner’s general impressions about the two POS and the advantages and disadvantages in the use of digital tools applied in the context of placemaking.

Table 1.

Dimensions of analysis to be considered in an ethnographic approach to support collaborative planning, as proposed within the scope of the CyberParks project.

Figure 1.

The Parque da Quinta das Conchas. CyberParks project archive (2014).

This study consisted of two main tools, the WAY CyberParks app [15] and GPS devices. The WAY CyberParks app is an application developed within the scope of the project. A questionnaire survey about the applicability of the tools (app and GPS) was also issued. The attendees were split into two large groups, which alternately visited the study areas. Group A first visited the Parque da Quinta das Conchas, and then the Jardim da Estrela, while Group B took the opposite route. Fifty-eight attendees participated in this study. During their visit, small groups of four to six attendees freely visited the parks together; both devices provided location data, while the WAY CyberParks app enabled posing location-specific questions for the attendees about the local qualities and amenities.

At the end of the visit, the two large groups met at Parque Eduardo VII, a central park in Lisbon, to collaboratively discuss the experiences with the site visits and the methodological tools and their appropriateness to obtain insights on people’s use of POS. In the following months, as part of local research, a set of workshops were implemented in Parque da Quinta das Conchas. These workshops aimed to gain better insights from POS users about the park and their suggestions for its improvement. Park users were asked to download the WAY CyberParks app and respond to an integrated questionnaire. This helped us also to identify preferred routes and stops patterns. The participants chose their routes freely and spontaneously. A large participation of young adults was noted.

On the one hand, the results from the field studies in Jardim da Estrela and Parque da Quinta das Conchas helped us to improve the reference guide for collaborative ethnographic perspective in placemaking activities, resulting in the dimensions described in Table 1. On the other hand, these studies enabled us to provide insights in considering participants of a collaborative study focused on placemaking as co-researchers. The term co-research and an approach to it are further developed in the following placemaking projects.

3.1.2. The Project C3Places—Using ICT for Co-Creation of Inclusive Public Places

C3Places aimed to explore co-creative approaches as a contribution to improving the quality of POSs, considering the promotion of social inclusion through the relationship between people, ICT, space and urban planning. The project focused on different categories of users and was carried out in four different European cities (Ghent, Lisbon, Milan and Vilnius). Living lab methodology was used in these different case studies and was of fundamental importance for the operationalization and evaluation of the implemented co-creative processes. For this article, we concentrate on the case study of Lisbon, Portugal. This case study focused on the perspectives of teenagers in the creation of POSs that are sensitive to their spatial needs [11]. To engage teenagers, the living labs took place in and with the support of a secondary school in Lisbon and involved teenage students aged 13–18. The workshops were integrated in the school within the scope of the Ministry of Education’s pilot project on curricular autonomy and flexibility, explaining the project and how this supports the involvement of teenage students with their environment.

For these workshops, a variety of techniques and tools were created, adapted and used to encourage teenagers to reflect on urban spaces (see Figure 2). These tools included, for example, site visits and neighborhood observation visits, questionnaires and interviews, discussion sessions, and debates, which guests from other institutions, like city council, and urban activists were invited to participate in. A series of four workshops, each subdivided into four sessions, were developed. Each series focused on a theme and had tailored tools. The workshops were organized in two phases, 2017/2018 and 2018/2019. In the first phase, 49 students from 10th grade, between 15 and 18 years old, participated.

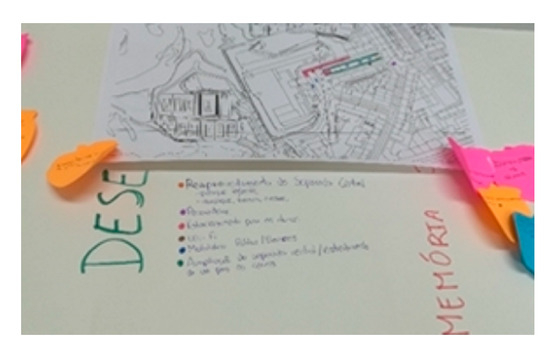

Figure 2.

Classroom activity in the first phase of the workshops: discussion about the ideal space to accommodate the needs of teenagers. C3Places project archive (2017).

In the second phase (2018–2019), 20 students from two classes in the first grade of technological and professional education (between 16 and 18 years old) participated. Collaborative work was encouraged in order to co-creatively identify and propose new ideas for a public space to be chosen by the teenage students (see Figure 3). The street in front of their school was selected as being of common interest. The workshops were developed into four sessions, each covering the following topics: introduction to urban planning, public space and co-creation; problems and potential of the selected space; spatial needs and wishes of students; co-creating ideas for the refurbishment of the street space in front of the school.

Figure 3.

Co-creative process for the transformation of a public space in Alvalade. C3Places project archive (2019).

Drawing and discussion techniques were the most preferred modalities among the several methodological resources applied. The students largely made use of drawing materials and tablets made available to them.

Throughout the entire case study, a dynamic process consisting of multiple components could be established:

- Effective communication with key stakeholders, the school community (school board, teachers, parents—the last contacted due to students’ need for parental permission to leave the school grounds, etc.) and local authorities (represented by Parish Council staff).

- Inquiries with students, teachers and the school board, and urban planning technicians by carrying out formal and informal interviews and questionnaires.

- Field observation by researchers at the POS around the school, considering their characteristics and features, youth spatial practices and behaviors in POS.

- Thematic workshops on urban planning, with debate sessions, exploratory site tours, idea exchange with representatives of the council and urban activists, and elaborating a design proposal for a teenager-sensitive POS.

- Board games and role-play as a participatory design tool to engage teenagers in co-creating POS.

- Site visits with teenagers’ mapping of qualities of POS around the school and their residences.

- Interactive interviews, collection and analysis of narratives on the use of POS and social contacts outdoors, and elaboration of a design for a teenager-sensitive POS.

- Recording, continuous review and improvement of methodology and results through fieldwork notes, photographic records, diagrams and continuous feedback from the living labs.

As a result of this collaborative ethnographic approach and its analysis applied in the Lisbon case study, the following aspects can be highlighted:

- The urban planning workshops provided the opportunity for continued observation and evaluation.

- The planning of the workshop was open enough to be updated after each evaluation, easing the reintegration of the dynamics and results of the previous sessions.

- Advanced insights into teenagers’ practices and behaviors regarding the interaction among themselves, in urban spaces and with the use of digital tools.

- Researchers also play a vital role as moderators and facilitators of the process. This was therefore relevant for implementing a co-research approach with the teenagers.

- Backed by the experiences in the four case studies, the project facilitated self-reflection among the researchers and stakeholders, and in the case of Lisbon, this reflection involved teenagers, the school board and the local planning staff.

3.1.3. Project Cyted RUN—Naturalized Urban Rivers

Backed by citizen science and collaborative methodologies, the Ibero-American network RUN—Naturalized Urban Rivers—brings together and forges discussions among different tenets of urban, ecological, hydrological, political and social research from 15 institutions in Europe and Latin America. Understood as an exchange platform, RUN aims to facilitate a constant and dynamic exchange of knowledge and experiences towards a more sustainable path in treating rivers that cross urban settings. The project is still running and will deliver enriched research and practical exercises to address, interrogate and inform strategies and policies, and this with the engagement of local riverain communities [16].

In Portugal, the project analyzes two strands—social memory and attachment to new local features. The first strand focuses on mapping and recovering social memories related to watercourses that are no longer visible in the cityscape of Lisbon. Because these watercourses are covered and imperceptible, even though they help to drain the city. Therefore, throughout the history of the evolution of the city of Lisbon, references to these watercourses were used in the city’s toponymy to name landscape, relief and topographical features. This case thus collects people’s narratives and analyzes historical documents and photographs. This research strand makes use of social media for collaborative mapping. Walking routes are planned for small groups (three to four people) in areas of Lisbon whose toponymy is rich in references to watercourses. It aims at raising awareness and enhancing the relationship between people and their surroundings, heritage and urban memory.

The second study was carried out along the Ribeira das Jardas on the outskirts of the city of Sintra, in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. The Ribeira das Jardas is a small stream that has been partially recovered and revegetated and has become the ecological backbone and the division line between two neighborhoods. In this case, we analyzed the role of a regenerated watercourse as an attraction for outdoor activities, e.g., leisure, physical activities, sports. The data collection encompassed field observations, interviews with users and, in particular, guided walking tours, with participants mapping qualities of the local environment (Figure 4).

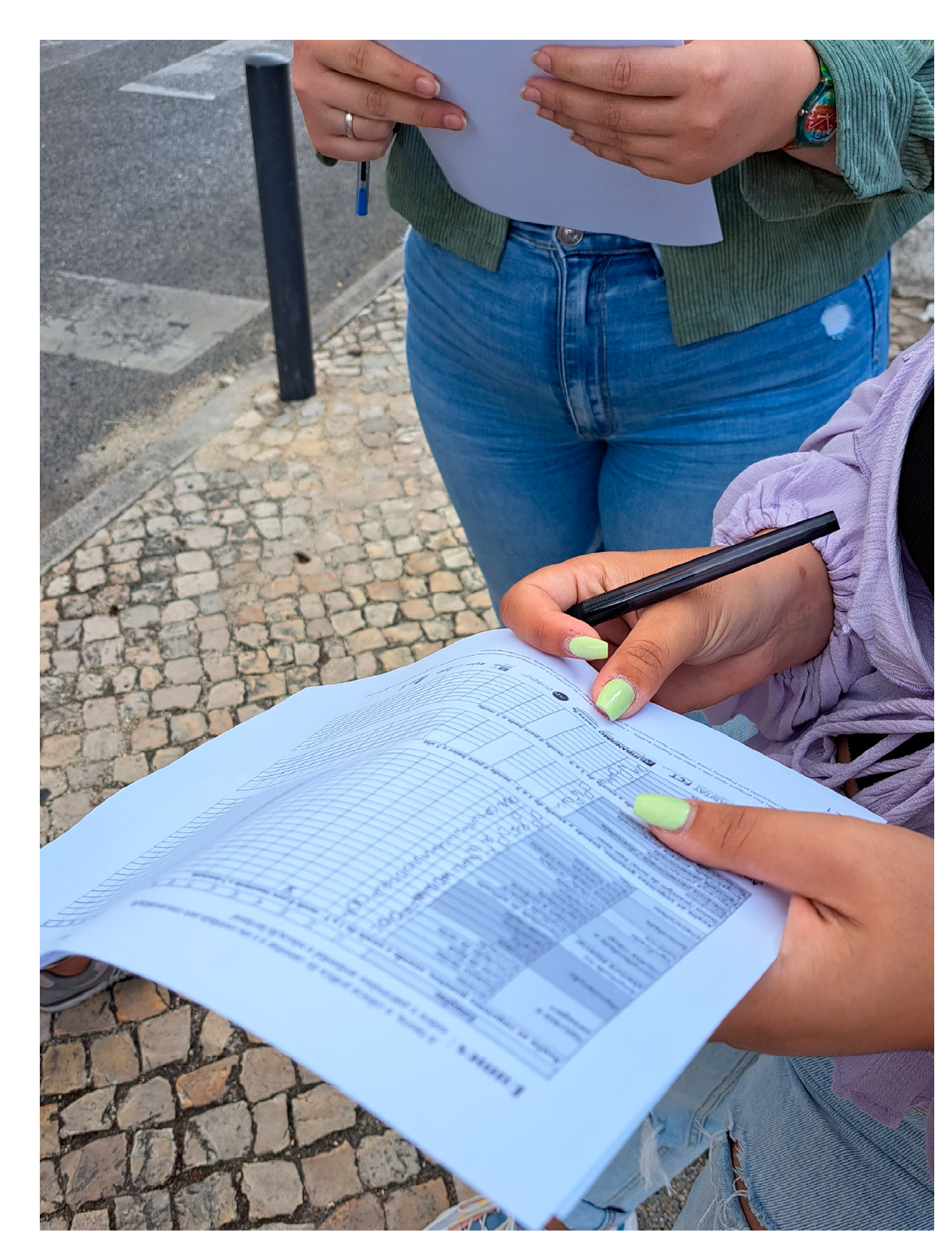

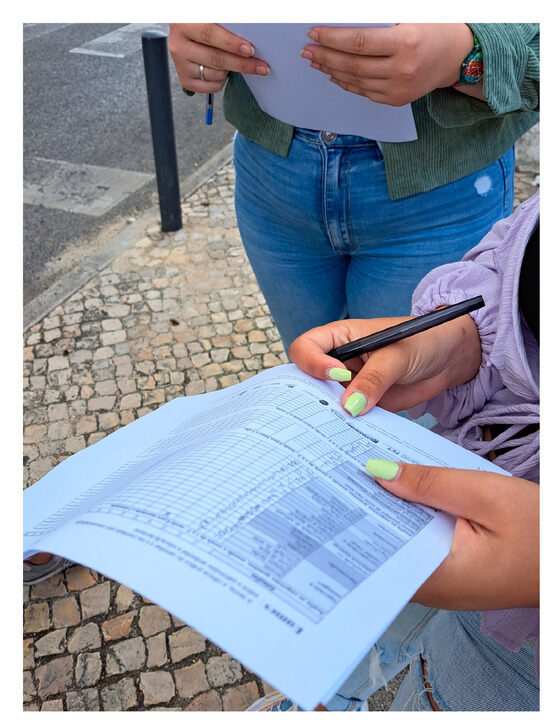

Figure 4.

Participants taking notes during the walking tour. The responses should reflect the group opinion. RUN project (2024).

The waking tour organized in July 2024 brought together 34 participants. A toolbox was developed to be used by each of the four groups the participants were divided into. Together with the local council, four routes and several stations along them were identified, having the Ribeira das Jardas as a backbone. The tools encompassed a route map, a questionnaire about the spatial qualities around the stations, guidelines for interviewing people the groups met along their walking and grid for observational research. For lay people, the use of a map to find their route was already a challenge. The results are still being analyzed.

The preliminary results of the two cases show that both strands of research and their approaches can contribute to a better understanding of how communities can be engaged with their rivers. The value of this engagement is evident through the following:

- Engagement of local communities in collaborative social mapping to contribute to the data repository, e.g., collecting information, documents, photos and narratives to explore lost, buried or disappeared watercourses and the past practices of use, as well as social and cultural appropriation of rivers and their banks.

- Support for building and enriching local knowledge, i.e., in walking tours, participants enjoy learning about local features and culture in their own environment.

- Promoting citizen science helps to communicating science and disseminating the results of collaborative studies to local and general audiences.

- Community-based approaches that foster the use of local ideas and practices. This exchange also fosters further development and consolidation of local knowledge.

- Community-led processes, which in turn play a crucial role in the empowerment of communities and thus strengthening sustainability and resilience.

- Guided tours, which were recognized as an exciting approach, besides being easy to put into practice, help to deepen the relational local quality with the perception and narratives of users.

- Most of all, from a strategic perspective, a fundamental aspect of river regeneration is not just about restoring the health of a water body, but also about reconnecting it to people’s lives.

Both case studies in Portugal enable us to discuss a better understanding of water-sensitive urban design, along with people’s agency and empowerment, and to explore new approaches of engagement and collaborative design.

4. Discussion

Exploring the contribution of ethnography from a collaborative perspective became fundamental within the framework of the three research projects around placemaking issues. These projects investigate the use of local knowledge in planning processes and how this can contribute to the production of more inclusive, attractive and responsive POS. A central issue in the projects is to consider the role digital and mobile technologies can play in the involvement of/with people in spatial planning. At the same time, leveraging the use of local knowledge and engagement technologies opens opportunities for experimenting with participatory, collaborative and co-creative methodologies.

4.1. An Ethnographic Approach to Spatial Research

An ethnographic perspective refers briefly to smaller-scale studies with greater proximity to the community and people in their environment. It stands out as an essential approach for obtaining more evidence-based knowledge about behavioral patterns, the relationship between the users (who and with whom), space and spatialities (where and what for), time and temporalities (when and how often) and objects and artefacts (with what and what for) [2,17]. As such, it contributes to capturing social diversity and complexity, a relevant issue considering that urban societies are becoming more and more diverse and heterogeneous. On the other side, it enables us to reflect on different people’s needs, interests and expectations, and to identify different perceptions, attributes and meanings attached to the POS. This ethnographic approach was also applied in the projects as an important resource for mapping social practices and collecting and recording data and information about the space production and appropriation processes [17].

An ethnographic approach always implies some kind of collaboration, such as the exchange of ideas and information between researchers and their interlocutors [18]. Its particularity lies, as a principle, in an ethical and moral commitment, in which the people involved in research are treated more than mere means for performing an analysis or a task [15,16,17,18]. Ethnography as a collaborative method has the ability to understand the “structure of research” together with the “problem to be addressed”; data are produced and interpreted collaboratively by researchers and interlocutors, enhancing a “dialogical construction of culture” [18] (pp. 61–62). Ethnography, as a collaborative method, prioritizes understanding the research process as far more important than the data collection itself. Thus, it deals with a collective and dynamic research process that helps understand contexts with a diversity of situations, resources (material and immaterial) and sensibilities [18]. The commitment to the collective construction of knowledge decouples the distinction between the researcher and the object of study [19,20,21]. This perspective has also been associated with the idea of public anthropology or applied anthropology [18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Collaborative ethnography is reflexive, it identifies subjectivities and is based on experiences between researchers and interlocutors and/or stakeholders. It is considered a practical process to elaborate the needs and objectives of the community [18]. The anthropologist’s knowledge and techniques are useful to stimulate joint debates around certain aspects that interest and impact the life of the community, contributing not only to the discussion but also to problematizing certain issues [18]. Hence, it is a researcher’s responsibility to share the (partial or final) results of the study [22,23,25]. Thus, the researcher’s role as mediator is reinforced, contradicting more unilateral and authoritarian academic positions [26]. The ethical effect of this perspective is reflected in terms of the research process and its results, and involves the researcher being in charge of sharing information, reasoning about the aims and objectives of the research, and exploring the potential impact that the research may have [19,20,21]. This also reflects in the way research products are prepared—in fact, they are co-elaborated [2]. Such a set of collaborative features places it under the concept of co-research [11,26], and makes collaborative ethnography, from a community-based perspective, of particular interest for participatory and co-creative urban design and planning processes [27].

By providing opportunities to jointly work out results and products, collaborative ethnography makes it possible to engage people in debates and create shared processes [19,24,28]. This fact shows that collaborative ethnography helps generate negotiated results. From a participatory planning perspective, collaborative ethnography highlights a co-creative commitment, in which the community’s and stakeholders’ engagement aims at achieving common and negotiated benefits.

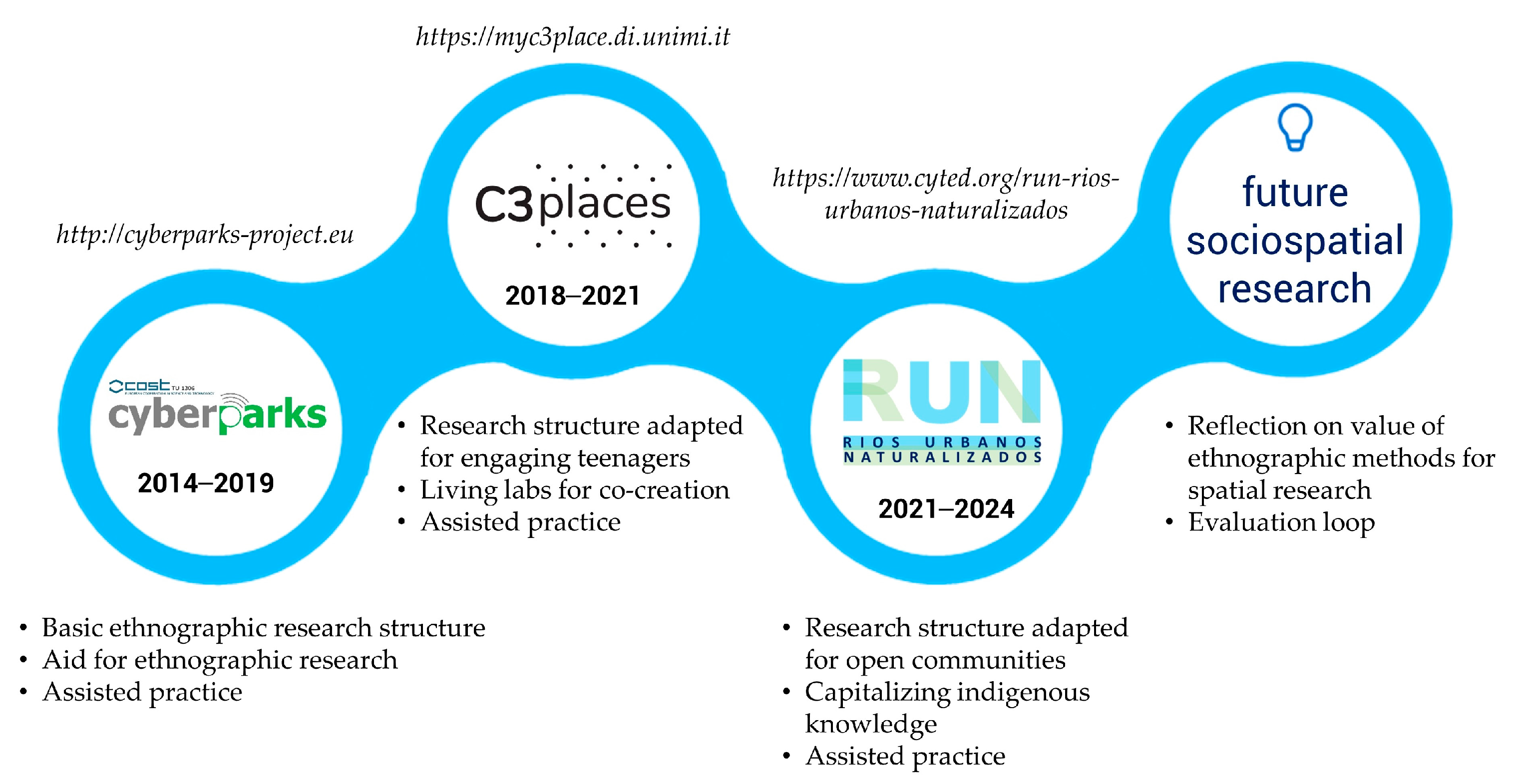

4.2. The Impact of Ethnographic Results for Spatial Research

Drawing on the acquired experiences and learnings within the research projects allows for us to reflect on the use of collaborative ethnographic methodologies for the production of POS that are more sensitive to people’s needs. The relationship between the research methodology and results shows us some learnings that can build an avenue for spatial research and placemaking. The process and progress on the use of this approach is synthesized in Figure 5, which depicts the evolution of the method considering the time frame of the three projects. In each project, an assisted practice (assessment of the process including the methods used) supported the evolution and further development of the approach.

Figure 5.

The time frame of the projects and the evolution of the research approach, (web accessed on 19 June 2024).

The format of collaborative ethnography could be applied to different topics and with various stakeholders within sociospatial research projects. This knowledge basis also allows drawing several lessons for multiple knowledge domains required for multi- and transdisciplinary practice for urban design and planning, such as for placemaking. Unlike more conventional ethnographic practice, the experiences explored within the three projects did not necessarily result in ethnographic reports. In line with the projects’ goals, collaborative ethnography was used for the collective creation of narratives, maps and proposals. Hence, several practical considerations arise from the studies reported here, which are of great relevance to urban development debate and practice, and to enrich the role of such research work in researchers’ training. The insights are as follows:

- The community becomes more actively engaged in co-creation processes when the process starts with valuing practices already in place and everyday practices, and concerns places in the immediate neighborhood.

- The added value of people becoming more aware of urban issues also brings significant societal benefits (empowerment, agency, etc.) and increases place attachment [27,29]. Additionally, for researchers, with the engagement activities, they also gained new skills in communicating with the public.

- A collaborative ethnography approach came to attention as a concrete tool in channeling and facilitating shifts between different contexts, i.e., between formal and informal processes, between different frameworks and institutional settings. In the case of teenagers, for example, it built the bridge between formal and informal learning environments, in the classroom and outdoors, in POS [11].

- Urban education can be a key in overcoming an identified urban illiteracy, i.e., the spatial ability to reflect on the role POS plays in the city’s dynamics, as well as difficulties among the participants in discussing, explaining and representing spatial situations and ideas.

- Alongside the regulatory planning, informal activities (co-creation labs, co-design workshops, collaborative mapping, etc.) can bring up new ideas and arguments [30,31,32], and be a means of leveraging support for public policy changes. This also requires intensive collaboration between the government and stakeholders.

- Co-creation incorporates the active involvement of concerned stakeholders, who become co-creators of their own environment [11,17]. The engagement in changing the environment is also relevant to reducing risks citizens may be exposed to, as in the case of riverine communities. This is also a way of creating experimental knowledge.

- Co-creation as a methodological process has to be deployed in an open and dynamic environment, with clear communication pathways [11]. Only this can guarantee the achievement of mutual benefits [5,9,11].

- It is imperative to record, analyze and interpret the dynamics that emerged during the activities (in the projects: living labs, workshops, walking tours, etc.), in order to prepare and enrich the follow-up actions, and to arrive at relevant conclusions.

- A comprehensive reflection on the co-creation dynamics also calls for self-assessment by facilitators, researchers and other participants, i.e., observers. A well-prepared team that is also familiarized with the context can efficiently influence the co-creation dynamics.

- The framework of collaborative ethnography enables us to gain valuable insights and evidence that can inform policymaking. It is also an act of collective creativity [15] leveraging “more realistic ideas” [21,23,24].

- The processes work better if the living lab manager teams involve at least three different tasks—a facilitator, a supporter, and an observer—with skills that complement one another. The facilitator guides the process and fosters interactions between the stakeholders. The supporter delivers aid and assistance to the group to enable them to achieve the goals, and the observer records the process and provides feedback to the manger teams in order to ensure among others that all participants are involved, and the tools appropriate. Such a division of tasks helps to better understand the process and fine-tune it.

- Collaborative ethnography contributes to building the framework and facilitating co-creation and co-research as a way of placemaking. It also helps to eliminate unbalanced relationships between researchers and focus groups, dealing thus with unequal power. Participatory processes entailing stakeholders also mean sharing power [33].

- ICT is becoming a backbone in participatory urban planning and co-creative POS initiatives [30,33], as digital and mobile technologies combine physical and digital structures and activities [12]. Although technology is increasingly becoming ubiquitous and pervasive, we understand them as mere artefacts, moderators and facilitators [30,34]. This implies that ICT tools must be accompanied by more “traditional” tools commonly used in social and urban research to ensure the needed completeness and the collection of meaningful qualitative data.

Along with these benefits, the collaborative ethnography approach has also some constraints. The research projects encountered, in particular, the following shortcomings, which had to be embraced through different actions:

- Low literacy on urban and territorial issues and associated difficulties in expressing and exposing ideas. This key challenge affects also a broad understanding that everyone should have a voice in creating a more responsive environment [2,4,11]. Also, locally rooted co-creation activities help to overcome the challenge of spatial literacy [11]. From the projects C3Places and RUN [11,13], it can also be noted that participation potential is enriched by games and walking tours, respectively. Both represent different ways of learning about the environment and urban planning [17,27].

- Another issue related to literacy is the need detected, prior to the engagement events (co-creation workshops, living labs, etc.), to develop comprehensive informative or training actions to clarify issues such as urban space, POS, common goods, etc.

- Difficulties in crossing borders and subtle boundaries that are created both by stakeholders and by a disciplinary understanding of how to approach an issue. Overcoming these barriers, however, plays a crucial role in addressing some of the world’s most pressing issues, regardless of their nature (i.e., social, environmental, etc.). Stakeholders, as people experienced in the projects, are aware that the outcomes from the engagement of a varied set of stakeholders can benefit from a reimagined set of solutions [8,11,22,24] because these can be more rooted in the area and be more creative.

- Lack of motivation to participate in co-creation events. One of the main reasons mentioned is the significant time lag between participating and co-developing ideas to ameliorate the environment, and to reap the benefits expected to derive from these ideas. This is an argument that remains difficult to refute, considering that urban planning is a complex and detailed process that often spans a considerable length of time between the initial development phase and actual implementation [11,27].

- Multi-stakeholders’ initiatives have to cope with complex relationships. Although this seeks to address issues of mutual concern, the development of ideas can be hindered by the solutions developed or the type of territorial transformation to be produced as an outcome. Here, the (disciplinary) expertise of the facilitators was demonstrated to be of great value, as an expert opinion would be more easily accepted. A careful and sensitive intervention of experts demonstrated helpfulness in the negotiation. On the other hand, the stakeholders were aware that both the ideas as well as the raised issues generated in the workshops enriched the research process and the outcomes. The outcomes of the projects also demonstrated that people’s agency and empowerment can bring about innovative action. This also challenges the decision-makers to provide responses to people’s needs and requests.

Despite these shortcomings, the results in the three different project contexts champion co-creation and co-research processes as an enabler to create opportunities for citizens to play different roles and co-produce realistic and “real life” outcomes. Closely linked to this, as asserts [33], places are important carriers of local knowledge and insights; making active use of these can leverage better tailored decisions and more responsive places. Given the complexity and the need for urban planning to create livable, sustainable and people-friendly cities, it is clear that extensive time investment in the planning and preparation of co-creation and co-research processes is essential to achieve these goals. A detailed, participatory and regulated approach helps to ensure that urban development serves the community’s long-term interests [27,31,32,33]. The ability to make informed decisions is critical for any innovation and to turn cities into more livable places.

5. Conclusions

Collaborative ethnography is explained and rationalized here as an umbrella concept, in which the theoretical framework, methodologies and tools are encompassed, although several other approaches and tools can be included. Such a set of tools opens up possibilities to create the potential for more equal, inclusive and engaging placemaking.

Reflecting on the values and impact of collaborative ethnography to drive social engagement enables us to enlarge the foundations for a theoretical framework of citizen science and participatory processes in urban planning. In this article, we outline a methodology for synthesizing and valuing community engagement with the purpose of developing ideas for a more people-friendly urban environment and community-led processes. We place emphasis on supporting the development of collaborative approaches, including ethnography and cooperation towards placemaking, and exerting a significant impact on the development of new urban discourses and planning practices—all understood as a process and not a final goal. Collaborative ethnography is a valuable contribution to spatial research and placemaking. It can connect researchers and communities, improve understanding of their needs and opinions, and involve the exchange and negotiation of ideas and information, among many other aspects. Besides that, the collaborative ethnographic approach provides more proximity to the study contexts, uncovering social and spatial aspects. Nevertheless, these aspects may be challenging to explore in depth, as they would require additional time to study and produce knowledge on, which sometimes is not possible within the time frame of research projects. In the projects and case studies reviewed, the use of collaborative ethnography allowed us to perceive some challenges and limitations, and to highlight areas for further exploration or improvement in future research.

It has also to be noticed that researchers reported gaining both new knowledge and skills from the citizens’ engagement, and use of local knowledge, in particular from working with groups whose voices are seldom heard in planning processes, i.e., teenagers. This new knowledge could be used for adapting and updating the design of research, interventions and new field activities. The discussion opened with this article shows that all social and spatial sciences can benefit from a collaborative ethnographic approach.

The time sequence of the projects, first CyberParks, followed by C3Places and now RUN, provided the opportunity to rethink the ethnographic approach in the ensuing projects and enabled us to create a sound scientific basis for future projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.; methodology, M.M. and C.S.C.; formal analysis, M.M. and C.S.C.; investigation, M.M. and C.S.C.; resources M.M. and C.S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M. and C.S.C.; supervision, C.S.C. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is partly supported by the project RUN—Naturalized Urban Rivers (funded by the Cyted—Ibero-American Science and Technology Programme, contract no. 420RT0008).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UN-Habitat. SDG Indicator 11.7.1 Training Module: Public Space; United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/07/indicator_11.7.1_training_module_public_space.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Menezes, M.; Smaniotto Costa, C. People, public space, digital technology and social practice: An ethnographic approach. In Enhancing Places through Technology, 1st ed.; Series Culture & Territory; Zammit, A., Kenna, T., Eds.; Lusófona University Press: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 167–180. ISBN 978-989-757-055-1. Available online: https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/46993 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Low, S. On the Plaza: The Politics of Public Space and Culture; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0292747142. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S. Spatializing Culture. An Engaged Anthropological Approach to Space and Place. In The People, Place, and Space Reader; Gieseking, J.J., Mangold, W., Katz, C., Low, S., Saegert, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781315816852. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipur, A. Espaço Público: O Espaço da Co-Presença. In O Lugar de Todos-Interpretar o Espaço Público Urbano; Brandão, A., Brandão, P., Eds.; Livraria Tigre de Papel: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019; pp. 13–18. ISBN 978-989-999-743-1. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipur, A. Rethinking Public Space; Geography, Planning and Tourism 2023; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettanini, T. Espaço e Ciências Humanas; Paz e Terra: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1982; ISBN 978-025-689-895-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dynamics of Placemaking and Digitization in Europe’s Cities. Available online: www.placemakingdynamics.eu (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Smaniotto Costa, C.; Fathi, M.; García-Esparza, J. (Eds.) Placemaking in Practice. In Experiences and Approaches from a Pan-European Perspective, 1st ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 1, ISBN 978-900-454-238-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Global Public Space Toolkit: From Global Principles to Local Policies and Practice; United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; ISBN 978-921-132-656-7. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2019/05/global_public_space_toolkit.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Smaniotto Costa, C.; Solipa, J.; Almeida, I.; Menezes, M. Exploring teenagers’ spatial practices and needs in light of new communication technologies. Cities 2020, 98, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyberparks Project—Fostering Knowledge about the Relationship between Information and Communication Technologies and Public Spaces Supported by Strategies to Improve Their Use and Attractiveness. Available online: https://cyberparks-project.eu (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- C3Places Project. Using ICT for Co-Creation of Inclusive Public Places. Available online: https://myc3place.di.unimi.it (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Cyted RUN Project. Citizen Science and Co-Creation for Regeneration of Urban Rivers and Mitigation of Risks. Available online: https://www.cyted.org/run-rios-urbanos-naturalizados (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Osaba, E.; Pierdicca, R.; Duarte, T.; Bahillo, A.; Mateus, D. Using ICTs for the Improvement of Public Open Spaces: The Opportunity Offered by CyberParks Digital Tools. In CyberParks—The Interface between People, Places and Technology; Smaniotto Costa, C., Erjavec, I.S., Kenna, T., Lange, M.D., Ioannidis, K., Maksymiuk, G., Waal, M.D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 278–293. ISBN 978-3-030-13416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaniotto Costa, C.; Menezes, M.; Pallares-Barbera, M.; Pastor, G.; Rocha, E.; Villalba Condori, K. Rios Urbanos na Ibero-América: Casos, Contextos e Experiências, 1st ed.; Series Culture & Territory; Lusófona University Press: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023; Volume 6, ISBN 978-989-757-239-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, M.; Arvanitidis, P.; Kenna, T.; Ivanova-Radovanova, P. People-Space-Technology: An Ethnographic Approach. In CyberParks—The Interface between People, Places and Technology, 1st ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Smaniotto Costa, S., Erjavec, I.S., Kenna, T., Lange, M.d., Ioannidis, K., Maksymiuk, G., Waal, M.D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11380, ISBN 978-3-030-13417-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzer, L.; Samprón, A. El trabajo de campo como proceso. La ‘etnografía colaborativa’ como perspectiva analítica. Rev. Latinoam. Metodol. Investig. Soc. 2011, 1, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Katzer, L.; Manzanelli, M. Etnografías Colaborativas y Comprometidas Contemporáneas; Asociación Argentina de Geofísicos y Geodestas: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2022; ISBN 978-987-252-915-4. Available online: https://biblioteca-repositorio.clacso.edu.ar/bitstream/CLACSO/169867/1/Etnografias-colaborativas.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Marcus, G.E. Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1995, 24, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D.R.; Marcus, G.E. Collaboration Today and the Re-Imagination of the Classic Scene of Fieldwork Encounter. Collab. Anthropol. 2008, 1, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassiter, L.E. Collaborative Ethnography and Public Anthropology. Curr. Anthropol. 2005, 46, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassiter, L.E. Collaborative ethnography. AnthroNotes 2004, 25, 1–20. Available online: https://ia803207.us.archive.org/31/items/anthronotesnat2512004hunt/anthronotesnat2512004hunt.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, J. Beyond Participant Observation: Collaborative Ethnography as Theoretical Innovation. Collab. Anthropol. 2008, 1, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catlin, J.N. Black like me: A shared ethnography. J. Urban Learn. Teach. Res. 2008, 4, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, R.G. Los Caminos Hacia la Investigación Colaborativa: Experiencias Etnográficas Junto a Movimientos por la Lucha de la Vivienda en Granada. Ph.D. Thesis, Programa de Doctorado Interuniversitario en Estudios Migratorios, Universidad de Granada, Universidad de Jaén, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Sevilla, Sapain, 2021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/71615 (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Schensul, J.J.; Berg, M.J.; Williamson, K.M. Challenging Hegemonies: Advancing Collaboration in Community-Based Participatory Action Research. Collab. Anthropol. 2008, 1, 102–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassiter, L.E. The Chicago Guide to Collaborative Ethnography; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 2005; ISBN 0-226-46889-5. [Google Scholar]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žlender, V.; Šuklje Erjavec, I.; Goličnik Marušić, B. Digitally Supported Co-creation within Public Open Space Development Process: Experiences from the C3Places Project and Potential for Future Urban Practice. Plan. Pract. Res. 2021, 36, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironowicz, I.; Ciesielski, M.M. Informal practices in urban planning and governance. Examples from Polish cities. Plan. Pract. Res. 2023, 38, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicher, C. Informal Urban Design. In Urban Design; Reicher, C., Ed.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022; pp. 311–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åström, J. Participatory Urban Planning: What Would Make Planners Trust the Citizens? Urban Plan. 2020, 5, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B.; Ihlström Eriksson, C.; Ståhlbröst, A. Places and Spaces within Living Labs. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2015, 5, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).