Factorization and Closed Form of Quantum Density Operators and Related Multiplicity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Definitions and Tools

2.1. Definition of Density Operator and Density Factor

2.2. Eigendecomposition of a Hermitian Matrix

2.3. Singular-Value Decomposition (SVD)

2.4. Fock Expansion (FOEX) and Thermal States

3. Multiplicity with Discrete Variables

Density Factors of a Given Density Operator

- (1)

- The minimum density factor of ρ. Consider the reduced EID of ρ:where are the r positive eigenvalues of are the corresponding orthonormal eigenvectors, , and . Then,is a minimum DF of ρ.

- (2)

- Arbitrary DF from a minimum DF. An arbitrary k-DF Φ of ρ is related to a reference minimum orthonormal DF in the form , where is an matrix given bywith being the diagonal matrix formed by the positive eigenvalues of ρ. The matrix always verifies the condition , where is the identity matrix of order r.

4. Closed-Form Factorization with Continuous Variables

4.1. State Matrices with Mixed States

4.2. How to Obtain a Factorization with Continuous Variables

4.3. Factorization of an Infinite-Dimensional Density Operator

5. Definition of Gaussian States

5.1. Generation of Gaussian States

5.2. Gaussian Unitaries from Primitive Gaussian Unitaries

- Displacement operator:

- Rotation operator:

- Squeeze operator:

- Switching rule: In a cascade, it is possible to switch the order of the FGUs by changing the parameters. For instance, , where .

5.3. Generation of Pure and Mixed Gaussian States

6. Fock Expansion of Pure and Mixed Gaussian States

6.1. Fock Expansion of Specific Gaussian States

- Noisy squeezed states (): There are not relevant simplifications with respect to the general case apart the use of the second form of Equation (32). Note that in Digital Quantum Communications, the use of this quantum states has no interest because the optical power comes from the displacement.

- Pure displaced states ():

6.2. Other Important Parameters for Quantum Communications

7. Application: Digital Data Quantum Communications Systems with Gaussian States

7.1. Numerical Problems with Noisy Gaussian States

7.2. State and Measurement Matrix, Gram Operator, and Optimal Quantum Decision

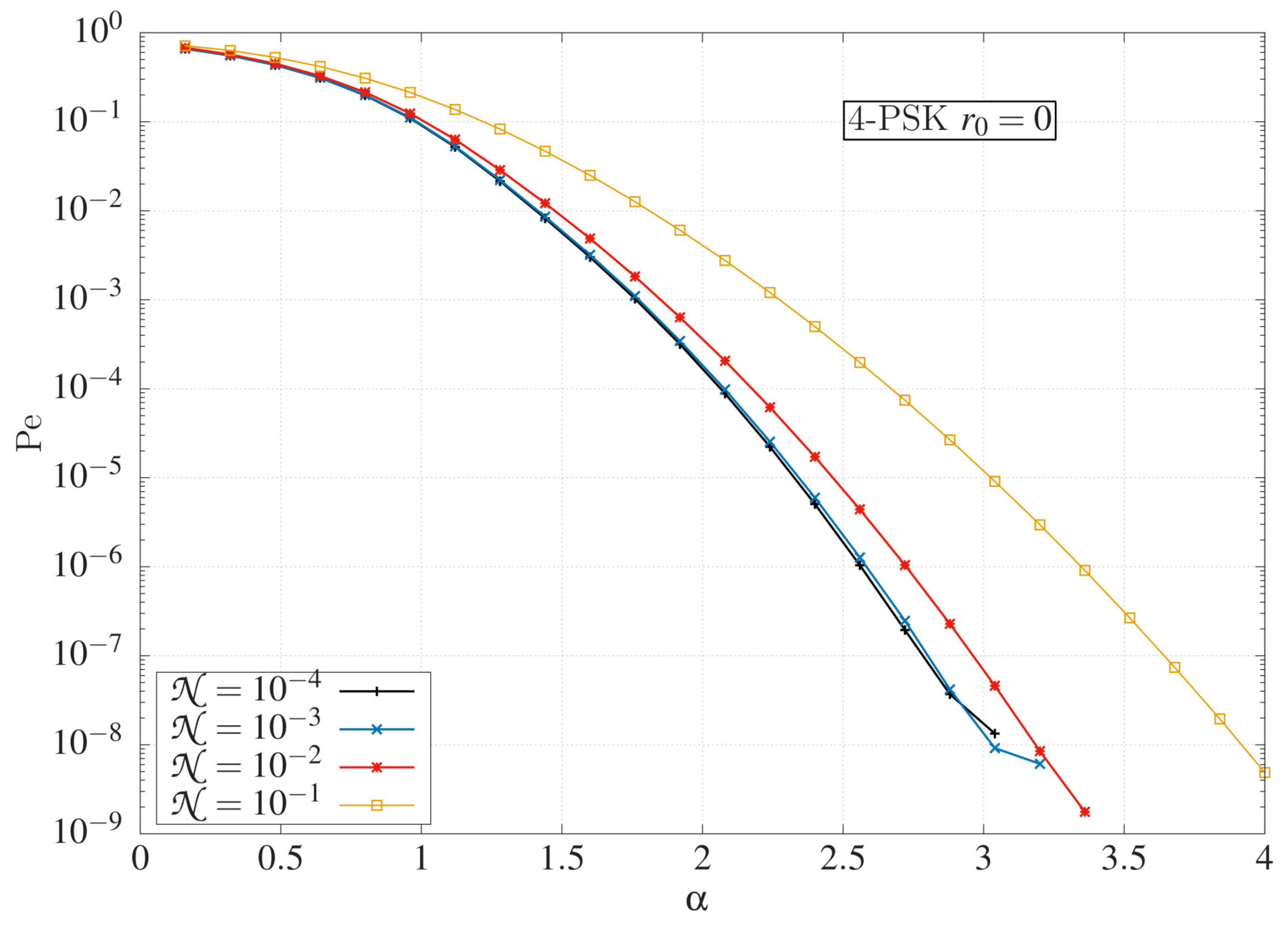

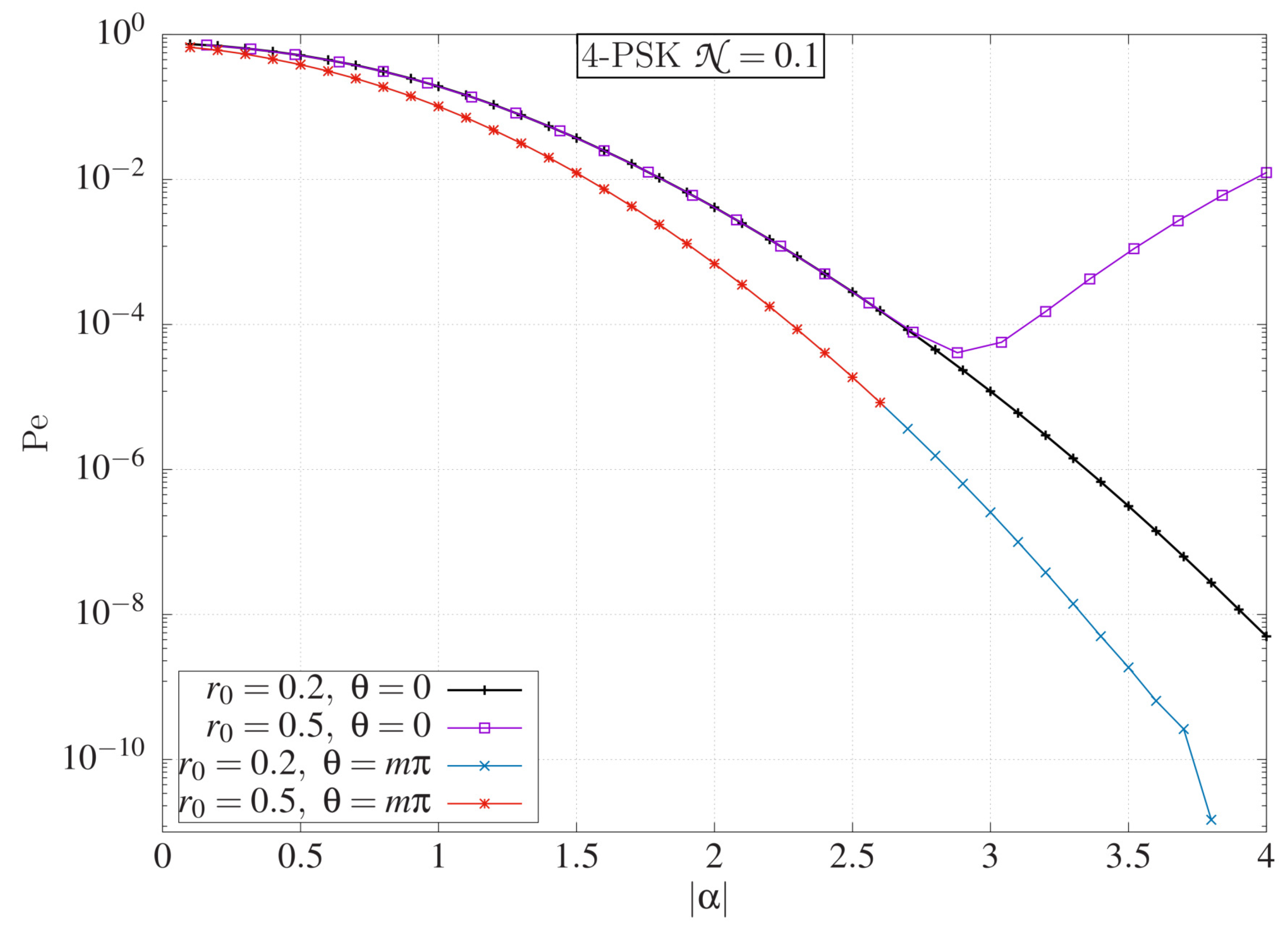

7.3. PSK Quantum Communications Systems in the Presence of Thermal Noise

Two Specific Examples

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DF | density factor |

| SVD | singular-valued decomposition |

| EID | eigendecomposition |

| FOEX | Fock expansion |

| PSD | positive semidefinite |

| SQRM | square root measurement |

| conjugate of the scalar c | |

| transpose conjugate of the matrix |

References

- Ma, X.; Rhodes, W. Squeezing in harmonic oscillator with time–dependent frequency. Phys. Rev. A 1989, 39, 1941–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Rhodes, W. Multimode squeeze operators and squeezed states. Phys. Rev. A 1990, 41, 4625–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, R.A.; Johnson, C.R. Matrix Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cariolaro, G. Quantum Communications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Weedbrook, C.; Pirandola, S.; García Patrón, R.; Cerf, N.J.; Ralph, T.C.; Shapiro, J.H.; Lloyd, S. Gaussian quantum information. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012, 84, 621–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauber, R.J. Quantum Theory of Optical Coherence: Selected Papers and Lectures; Wiley-VCH: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hugston, L.P.; Josa, R.; Wooters, W.K. A complete classification of quantum ensembles having a given density matrix. Phys. Lett. A 1993, 183, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierobon, G.; Cariolaro, G.; Dattoli, G. Fock, Expansion of multimode pure Gaussian states. J. Math. Phys. 2015, 56, 122109. [Google Scholar]

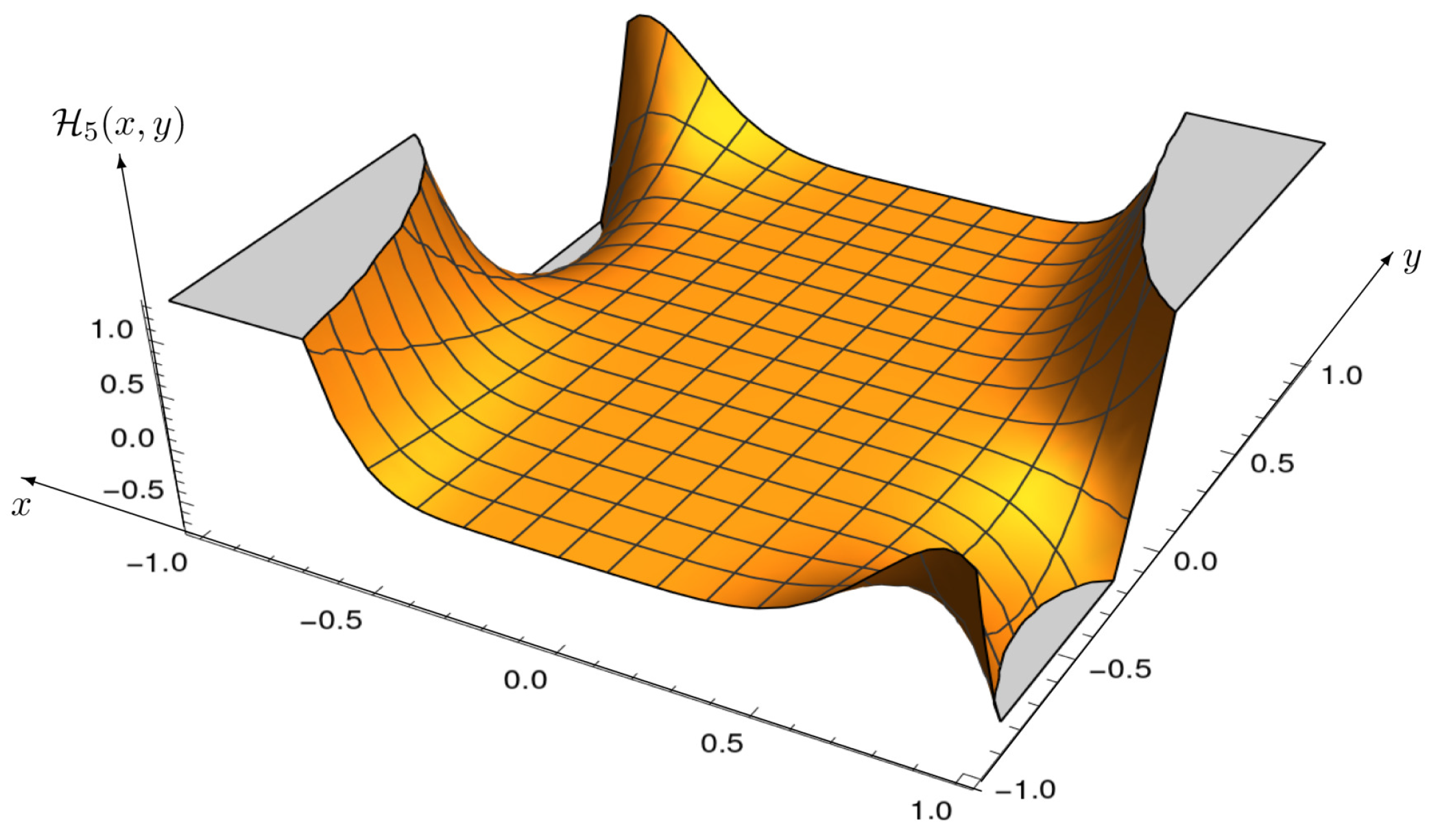

- Dattoli, G. Incomplete 2D Hermite polynomials: Properties and applications. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2003, 284, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.P. Two-photon coherent states of the radiation field. Phys. Rev. A 1976, 13, 2226–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.P.; Kennedy, R.; Lax, M. Optimum testing of multiple hypotheses in quantum detection theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1975, 21, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helstrom, C.W.; Liu, J.W.S.; Gordon, J.P. Quantum–mechanical communication theory. Proc. IEEE 1970, 10, 1578–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holevo, A.S. Statistical decision theory for quantum systems. J. Multivar. Anal. 1973, 3, 337–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldar, Y.C.; Megretski, A.; Verghese, G.C. Optimal detection of symmetric mixed quantum states. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 2004, 50, 1198–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, G.S.; Tara, K. Nonclassical properties of states generated by the excitations on a coherent state. Phys. Rev. A 1991, 43, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrini, S.; Win Moe, Z.; Chiani, M.; Conti, A. Quantum Discrimination of Noisy Photon–Added Coherent States. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Inf. Theory 2020, 1, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walschaers, M. Non–Gaussian quamtum states and where to find them. PRX Quantum 2021, 2, 030204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cariolaro, G.; Ruffa, E. Factorization and Closed Form of Quantum Density Operators and Related Multiplicity. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010013

Cariolaro G, Ruffa E. Factorization and Closed Form of Quantum Density Operators and Related Multiplicity. AppliedMath. 2025; 5(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleCariolaro, Gianfranco, and Edi Ruffa. 2025. "Factorization and Closed Form of Quantum Density Operators and Related Multiplicity" AppliedMath 5, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010013

APA StyleCariolaro, G., & Ruffa, E. (2025). Factorization and Closed Form of Quantum Density Operators and Related Multiplicity. AppliedMath, 5(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010013